10.5 The Tyranny and Triumph of the Majority

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain Alexis de Tocqueville’s analysis of American democracy

- Describe the election of 1840 and its outcome

To some observers, the rise of democracy in the United States raised troubling questions about the new power of the majority to silence minority opinion. As the will of the majority became the rule of the day, everyone outside of mainstream White American opinion, especially Native American and Black people, was vulnerable to the wrath of the majority. Some worried that the rights of those who opposed the will of the majority would never be safe. Mass democracy also shaped political campaigns as never before. The 1840 presidential election marked a significant turning point in the evolving style of American democratic politics.

Alexis de Tocqueville

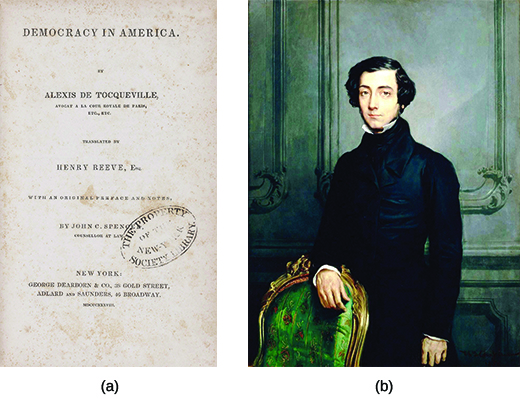

Perhaps the most insightful commentator on American democracy was the young French aristocrat Alexis de Tocqueville, whom the French government sent to the United States to report on American prison reforms (Figure 10.17). Tocqueville marveled at the spirit of democracy that pervaded American life. Given his place in French society, however, much of what he saw of American democracy caused him concern.

Tocqueville’s experience led him to believe that democracy was an unstoppable force that would one day overthrow monarchy around the world. He wrote and published his findings in 1835 and 1840 in a two-part work entitled Democracy in America. In analyzing the democratic revolution in the United States, he wrote that the major benefit of democracy came in the form of equality before the law. A great deal of the social revolution of democracy, however, carried negative consequences. Indeed, Tocqueville described a new type of tyranny, the tyranny of the majority, which overpowers the will of minorities and individuals and was, in his view, unleashed by democracy in the United States.

In this excerpt from Democracy in America, Alexis de Tocqueville warns of the dangers of democracy when the majority will can turn to tyranny:

When an individual or a party is wronged in the United States, to whom can he apply for redress? If to public opinion, public opinion constitutes the majority; if to the legislature, it represents the majority, and implicitly obeys its injunctions; if to the executive power, it is appointed by the majority, and remains a passive tool in its hands; the public troops consist of the majority under arms; the jury is the majority invested with the right of hearing judicial cases; and in certain States even the judges are elected by the majority. However iniquitous or absurd the evil of which you complain may be, you must submit to it as well as you can.

The authority of a king is purely physical, and it controls the actions of the subject without subduing his private will; but the majority possesses a power which is physical and moral at the same time; it acts upon the will as well as upon the actions of men, and it represses not only all contest, but all controversy. I know no country in which there is so little true independence of mind and freedom of discussion as in America.

Click and Explore

Take the Alexis de Tocqueville Tour to experience nineteenth-century America as Tocqueville did, by reading his journal entries about the states and territories he visited with fellow countryman Gustave de Beaumont. What regional differences can you draw from his descriptions?

The 1840 Election

The presidential election contest of 1840 marked the culmination of the democratic revolution that swept the United States. By this time, the second party system had taken hold, a system whereby the older Federalist and Democratic-Republican Parties had been replaced by the new Democratic and Whig Parties. Both Whigs and Democrats jockeyed for election victories and commanded the steady loyalty of political partisans. Large-scale presidential campaign rallies and emotional propaganda became the order of the day. Voter turnout increased dramatically under the second party system. Roughly 25 percent of eligible voters had cast ballots in 1828. In 1840, voter participation surged to nearly 80 percent.

The differences between the parties were largely about economic policies. Whigs advocated accelerated economic growth, often endorsing federal government projects to achieve that goal. Democrats did not view the federal government as an engine promoting economic growth and advocated a smaller role for the national government. The membership of the parties also differed: Whigs tended to be wealthier; they were prominent planters in the South and wealthy urban northerners—in other words, the beneficiaries of the market revolution. Democrats presented themselves as defenders of the common people against the elite.

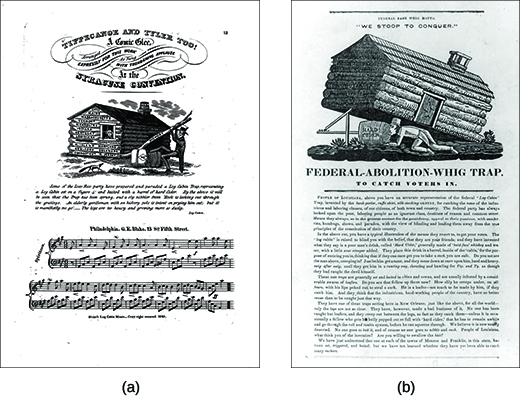

In the 1840 presidential campaign, taking their cue from the Democrats who had lionized Jackson’s military accomplishments, the Whigs promoted William Henry Harrison as a war hero based on his 1811 military service against the Shawnee chief Tecumseh at the Battle of Tippecanoe. John Tyler of Virginia ran as the vice presidential candidate, leading the Whigs to trumpet, “Tippecanoe and Tyler too!” as a campaign slogan.

The campaign thrust Harrison into the national spotlight. Democrats tried to discredit him by declaring, “Give him a barrel of hard [alcoholic] cider and settle a pension of two thousand a year on him, and take my word for it, he will sit the remainder of his days in his log cabin.” The Whigs turned the slur to their advantage by presenting Harrison as a man of the people who had been born in a log cabin (in fact, he came from a privileged background in Virginia), and the contest became known as the log cabin campaign (Figure 10.18). At Whig political rallies, the faithful were treated to whiskey made by the E. C. Booz Company, leading to the introduction of the word “booze” into the American lexicon. Tippecanoe Clubs, where booze flowed freely, helped in the marketing of the Whig candidate.

The Whigs’ efforts, combined with their strategy of blaming Democrats for the lingering economic collapse that began with the hard-currency Panic of 1837, succeeded in carrying the day. A mass campaign with political rallies and party mobilization had molded a candidate to fit an ideal palatable to a majority of American voters, and in 1840 Harrison won what many consider the first modern election.