13.5 Women’s Rights

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain the connections between abolition, reform, and antebellum feminism

- Describe the ways antebellum women’s movements were both traditional and revolutionary

Women took part in all the antebellum reforms, from transcendentalism to temperance to abolition. In many ways, traditional views of women as nurturers played a role in encouraging their participation. Women who joined the cause of temperance, for example, amplified their accepted role as moral guardians of the home. Some women advocated a much more expansive role for themselves and their peers by educating children and men in solid republican principles. But it was their work in antislavery efforts that served as a springboard for women to take action against gender inequality. Many, especially northern women, came to the conclusion that they, like enslaved people, were held in shackles in a society dominated by men. Even men who were progressive on some issues, such as abolition, adhered to traditional gender roles and demanded that their families did as well. Women also had very limited rights regarding property ownership and legal authority. Until states began passing property laws in the 1840s, husbands often fully controlled women’s earnings, collection of debts, and rights regarding inheritance. The laws gave women some additional power, but that power was far from universal.

Despite the radical nature of their effort to end slavery and create a biracial society, most abolitionist men clung to traditional notions of proper gender roles. White and Black women, as well as free Black men, were forbidden from occupying leadership positions in the AASS. Because women were not allowed to join the men in playing leading roles in the organization, they formed separate societies, such as the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society, the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society, and similar groups.

The Grimké Sisters

Two leading abolitionist women, Sarah and Angelina Grimké, played major roles in combining the fight to end slavery with the struggle to achieve female equality. The sisters had been born into a prosperous slaveholding family in South Carolina. Both were caught up in the religious fervor of the Second Great Awakening, and they moved to the North and converted to Quakerism.

In the mid-1830s, the sisters joined the abolitionist movement, and in 1837, they embarked on a public lecture tour, speaking about immediate abolition to “promiscuous assemblies,” that is, to audiences of women and men. This public action thoroughly scandalized respectable society, where it was unheard of for women to lecture to men. William Lloyd Garrison endorsed the Grimké sisters’ public lectures, but other abolitionists did not. Their lecture tour served as a turning point; the reaction against them propelled the question of women’s proper sphere in society to the forefront of public debate.

The Declaration of Rights and Sentiments

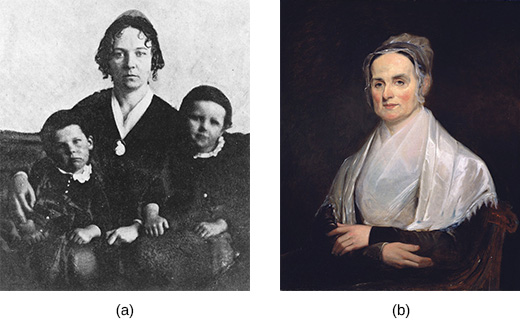

Participation in the abolitionist movement led some women to embrace feminism, the advocacy of women’s rights. Lydia Maria Child, an abolitionist and feminist, observed, “The comparison between women and the colored race is striking . . . both have been kept in subjection by physical force.” Other women, including Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Lucy Stone, and Susan B. Anthony, agreed (Figure 13.18).

In 1848, about three hundred male and female feminists, many of them veterans of the abolition campaign, gathered at the Seneca Falls Convention in New York for a conference on women’s rights that was organized by Lucretia Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. It was the first of what became annual meetings that have continued to the present day. Attendees agreed to a “Declaration of Rights and Sentiments” based on the Declaration of Independence; it declared, “We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men and women are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” “The history of mankind,” the document continued, “is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations on the part of man toward woman, having in direct object the establishment of an absolute tyranny over her.”

Click and Explore

Read the entire text of the Declaration of Rights and Sentiments in the Internet Modern History Sourcebook at Fordham University.

Republican Motherhood in the Antebellum Years

Some northern female reformers saw new and vital roles for their sex in the realm of education. They believed in traditional gender roles, viewing women as inherently more moral and nurturing than men. Because of these attributes, the feminists argued, women were uniquely qualified to take up the roles of educators of children.

Catherine Beecher, the daughter of Lyman Beecher, pushed for women’s roles as educators. In her 1845 book, The Duty of American Women to Their Country, she argued that the United States had lost its moral compass due to democratic excess. Both “intelligence and virtue” were imperiled in an age of riots and disorder. Women, she argued, could restore the moral center by instilling in children a sense of right and wrong. Beecher represented a northern, middle-class female sensibility. The home, especially the parlor, became the site of northern female authority.

Defining American

Sojourner Truth, “Ain’t I A Woman?”

Born into slavery with the name Isabella Baumfree, Sojourner Truth gained her freedom in 1826 and devoted much of the rest of her life to championing the causes of abolition and women’s rights. She became the first Black woman to win a lawsuit against a White person when she sued to gain the freedom of her son. Supported by leaders such as Frederick Douglass and William Lloyd Garrison, Truth became a powerful voice in the abolition movement. But she was not afraid to challenge the prevailing notions about the rights and priorities of men and women within the abolition movement, nor did she avoid challenging the notions about Black people’s priority within the women’s rights movement. While some advocated with a step-by-step approach—first White women’s suffrage, then Black women’s suffrage—Truth disagreed.

In 1851, Truth delivered a speech at the Women’s Rights Convention in Akron, Ohio. Ultimately, it came to be titled “Ain’t I a Woman.” One of the most famous transcriptions of this speech was published in an 1851 edition of the Anti-Slavery Bugle by Reverend Marius Robinson, an Ohio abolitionist who had worked with Truth. Another was published in an 1863 edition of the Anti-Slavery Standard by Frances Dana Gage, an abolitionist and feminist who presided over the convention at which Truth spoke.

I have as much muscle as any man, and can do as much work as any man. I have plowed and reaped and husked and chopped and mowed, and can any man do more than that? I have heard much about the sexes being equal; I can carry as much as any man, and can eat as much too, if I can get it. I am strong as any man that is now.

As for intellect, all I can say is, if woman have a pint and man a quart—why can’t she have her little pint full? You need not be afraid to give us our rights for fear we will take too much—for we won’t take more than our pint’ll hold.

The poor men seem to be all in confusion and don’t know what to do. Why children, if you have woman’s rights give it to her and you will feel better. You will have your own rights, and they won’t be so much trouble.

I can’t read, but I can hear. I have heard the Bible and have learned that Eve caused man to sin. Well if woman upset the world, do give her a chance to set it right side up again.

What might be the reasons for the different versions of Truth’s speech? Could the different publishers have had different motivations?

What is Truth’s theme in this speech?