14.4 John Brown and the Election of 1860

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry and its results

- Analyze the results of the election of 1860

Events in the late 1850s did nothing to quell the country’s sectional unrest, and compromise on the issue of slavery appeared impossible. Lincoln’s 1858 speeches during his debates with Douglas made the Republican Party’s position well known; Republicans opposed the extension of slavery and believed a Slave Power conspiracy sought to nationalize the institution. They quickly gained political momentum and took control of the House of Representatives in 1858. Southern leaders were divided on how to respond to Republican success. Southern extremists, known as “Fire-Eaters,” openly called for secession. Others, like Mississippi senator Jefferson Davis, put forward a more moderate approach by demanding constitutional protection of slavery.

John Brown

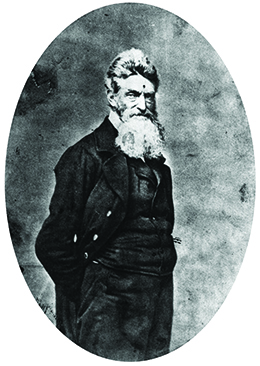

In October 1859, the radical abolitionist John Brown and eighteen armed men, both Black and White, attacked the federal arsenal in Harpers Ferry, Virginia. They hoped to capture the weapons there and distribute them among enslaved people to begin a massive uprising that would bring an end to slavery. Brown had already demonstrated during the 1856 Pottawatomie attack in Kansas that he had no patience for the nonviolent approach preached by pacifist abolitionists like William Lloyd Garrison. Born in Connecticut in 1800, Brown (Figure 14.18) spent much of his life in the North, moving from Ohio to Pennsylvania and then upstate New York as his various business ventures failed. To him, slavery appeared to be an unacceptable evil that had to be purged from the land, and like his Puritan forebears, he believed in using the sword to defeat the ungodly.

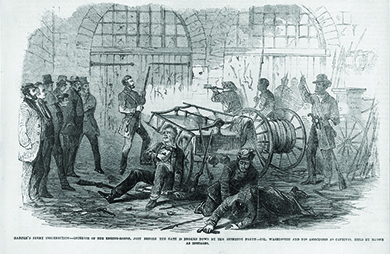

Brown had gone to Kansas in the 1850s in an effort to stop slavery, and there, he had perpetrated the killings at Pottawatomie. He told other abolitionists of his plan to take Harpers Ferry Armory and initiate a massive slave uprising. Some abolitionists provided financial support, while others, including Frederick Douglass, found the plot suicidal and refused to join. On October 16, 1859, Brown’s force easily took control of the federal armory, which was unguarded (Figure 14.19). However, his vision of a mass uprising failed completely. Very few enslaved people lived in the area to rally to Brown’s side, and the group found themselves holed up in the armory’s engine house with townspeople taking shots at them. Federal troops, commanded by Colonel Robert E. Lee, soon captured Brown and his followers. On December 2, Brown was hanged by the state of Virginia for treason.

Click and Explore

Visit the Avalon Project on Yale Law School’s website to read the impassioned speech that Henry David Thoreau delivered on October 30, 1859, arguing against the execution of John Brown. How does Thoreau characterize Brown? What does he ask of his fellow citizens?

John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry generated intense reactions in both the South and the North. Southerners grew especially apprehensive of the possibility of other violent plots. They viewed Brown as a terrorist bent on destroying their civilization, and support for secession grew. Their anxiety led several southern states to pass laws designed to prevent rebellions by the enslaved. It seemed that the worst fears of the South had come true: A hostile majority would stop at nothing to destroy slavery. Was it possible, one resident of Maryland asked, to “live under a government, a majority of whose subjects or citizens regard John Brown as a martyr and Christian hero?” Many antislavery northerners did in fact consider Brown a martyr to the cause, and those who viewed slavery as a sin saw easy comparisons between him and Jesus Christ.

The Election of 1860

The election of 1860 threatened American democracy when the elevation of Abraham Lincoln to the presidency inspired secessionists in the South to withdraw their states from the Union.

Lincoln’s election owed much to the disarray in the Democratic Party. The Dred Scott decision and the Freeport Doctrine had opened up huge sectional divisions among Democrats. Though Brown did not intend it, his raid had furthered the split between northern and southern Democrats. Fire-Eaters vowed to prevent a northern Democrat, especially Illinois’s Stephen Douglas, from becoming their presidential candidate. These proslavery zealots insisted on a southern Democrat.

The Democratic nominating convention met in April 1860 in Charleston, South Carolina. However, it broke up after northern Democrats, who made up a majority of delegates, rejected Jefferson Davis’s efforts to protect slavery in the territories. These northern Democratic delegates knew that supporting Davis on this issue would be very unpopular among the people in their states. A second conference, held in Baltimore, further illustrated the divide within the Democratic Party. Northern Democrats nominated Stephen Douglas, while southern Democrats, who met separately, put forward Vice President John Breckinridge from Kentucky. The Democratic Party had fractured into two competing sectional factions.

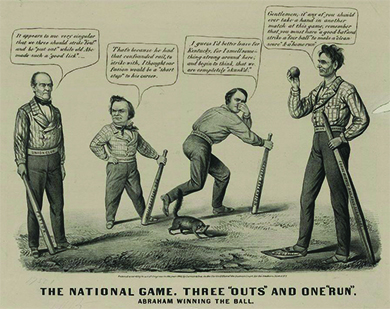

By offering two candidates for president, the Democrats gave the Republicans an enormous advantage. Also hoping to prevent a Republican victory, pro-Unionists from the border states organized the Constitutional Union Party and put up a fourth candidate, John Bell, for president, who pledged to end slavery agitation and preserve the Union but never fully explained how he’d accomplish this objective. In a pro-Lincoln political cartoon of the time (Figure 14.20), the presidential election is presented as a baseball game. Lincoln stands on home plate. A skunk raises its tail at the other candidates. Holding his nose, southern Democrat John Breckinridge holds a bat labeled “Slavery Extension” and declares “I guess I’d better leave for Kentucky, for I smell something strong around here, and begin to think, that we are completely skunk’d.”

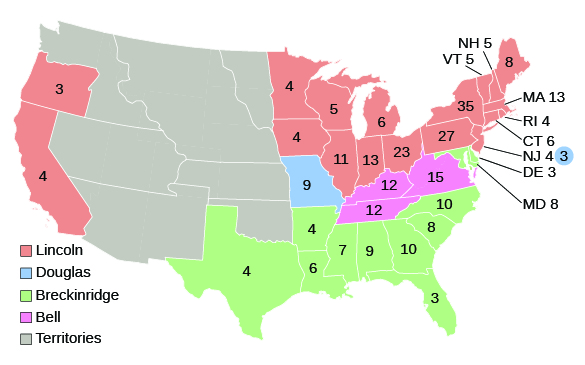

The Republicans nominated Lincoln, and in the November election, he garnered a mere 40 percent of the popular vote, though he won every northern state except New Jersey. (Lincoln’s name was blocked from even appearing on many southern states’ ballots by southern Democrats.) More importantly, Lincoln did gain a majority in the Electoral College (Figure 14.21). The Fire-Eaters, however, refused to accept the results. With South Carolina leading the way, Fire-Eaters in southern states began to withdraw formally from the United States in 1860. South Carolinian Mary Boykin Chesnut wrote in her diary about the reaction to Lincoln’s election. “Now that the Black radical Republicans have the power,” she wrote, “I suppose they will Brown us all.” Her statement revealed many southerners’ fear that with Lincoln as president, the South could expect more mayhem like the John Brown raid.