1 Chapter 1 – Crime and Criminology

Brandon Hamann

Learning Objectives

This chapter introduces the concept of crime and the study of Criminology. After reading this chapter, students will be able to:

- Identify the influences that determine the concept of crime.

- Describe the functions of the study of Criminology as it pertains to crime.

- Differentiate between legalistic and conflict perspectives.

February 26, 2012, Florida. A young Black man is walking home from the convenience store. It is late in the evening, his parents are out having a quiet dinner to themselves. A neighborhood watch (NW) volunteer spots the young man, and since he is unfamiliar with the person walking through his community, calls the police and reports the individual as suspicious. NW confronts the young man, asks him what he is doing in his neighborhood, and attempts to block his movements until the authorities arrive. A scuffle ensues, the two fight, the young Black man and NW are wrestling each other on the ground. NW pulls out his weapon and shoots the young Black man, killing him.

When the police arrive, NW claims that he shot the young man in self-defense. Police investigators can find no evidence to the contrary, and no charges are filed against NW. Public outcry over the incident is massive, to the point that the District Attorney is compelled to charge NW with 2nd degree murder and sends the case to trial. NW is later acquitted of all charges by a jury of his peers.

The young black man’s name is Trayvon Martin. He is 17 years old.

NW is George Zimmerman.

The question to be answered is: Was this a crime? Of course the first inclination is to say unequivocally yes. In fact, public opinion to this day suggests that Mr. Zimmerman did indeed commit murder in the death of Trayvon Martin. However, according to a court of law, no such crime occurred, regardless of how senseless and tragic the outcome.

Think about it for a minute: How do we define what is and what is not a crime? What influences do we draw on when considering what behavior(s) we as a society determine to be acceptable, and what is not? And who do we trust with the task of communicating those determinations to the entirety of the community?

What is Crime?

Each of us comes to criminology with our own understanding of what constitutes crime. In this chapter, you will learn how criminologists define crime, and the different ways societies respond to criminal behavior. We will first consider how crime was explained in the classical period of criminology. We will also consider the tension between legalistic and social constructionist approaches to crime, and how criminological theories can be classified into consensus versus conflict-based perspectives.

The term “crime” derives from the Latin word crīmen, which means the intentional commission of an act usually deemed socially harmful or dangerous and specifically defined, prohibited, and punishable under criminal law (Britannica.com, 2024). Many people take crime to mean a violation of criminal and codified law, but in English the term has always carried broader meanings and has never been restricted to legal codes (Quinney & Wildeman, The problem of crime: A peace and social justice perspective., 1991). Early Christian writers, for example, frequently used the word crime as a synonym for sin regardless of secular laws, and English speakers commonly use the term to talk about any offense or shameful act, such committing a fashion crime (OED, 2022). While criminologists do not typically concern themselves with fashion, the types of behaviors studied can range from minor acts of deviance to serious violations of criminal law.

Personal Statement

Brandon Hamann – Dillard University

I grew up “nuclear.” What that means is my family was considered the norm for the times: 2 parents, multiple children, owned a home, a car or two, had pets, swimming pool, and a fenced-in yard. My parents moved my brothers and me from Saint Bernard Parish to Saint Tammany Parish when I was three, in hopes of finding better opportunities for work and school. My father was a Vietnam Veteran and machinist/mechanic. My mother was a homemaker; taking care of 3 rambunctious boys was a job in of itself. My parents were able to buy their first home based off of my father’s Military service at a low interest rate, so we began anew in a different town.

We grew up not wanting of anything: Dad worked and provided, Mom stayed home and did what housewives do. Our neighborhood was made up of the same types of families: all first-time home buyers with young children trying to make it. On my street alone there were at least 10 kids all within the same age range. We went to the same schools, played on the same sports teams, went to the same churches, etc. Likewise our parents were all familiar with each other. They hosted get togethers, established a Neighborhood Watch, and generally stayed in touch with each other while we kids went off on our “adventures.” We were kicked out of the house after breakfast and told not to come home until the street lights came on. And this was all before the Internet and cellphones.

We were good kids, but not unaccustomed to a little troublemaking from time to time. We got into fights, did a little property damage, and generally raised a little hell. My first instance of true “crime” came at a fairly young age. Our group of friends would walk up to the local convenience store, one of us would distract the cashier by actually buying something while the rest of us filled our pockets with whatever candy we could get our hands on. We would then leave, run to the woods nearby, and divide up our loot amongst ourselves. Did we know we were committing theft? Of course we did, but we were bored and looking for some excitement. I was 10 years old.

Needless to say we all knew the difference between right and wrong. Our parents would constantly remind us, our church would constantly remind us, our teachers would constantly remind us, every grown up on our street would constantly remind us of what was good behavior and what was bad behavior.

What is Criminology?

Criminology, the scientific study of crime causation, first emerged within Europe in the late 19th century (Boyd, 2015). Of course, people had been dealing with crime and deviance long before this time, but no one had given it any thought as to its origin. Criminology had been in the purview of Sociology, but later branched off into its own field of study. But how did it begin? Honestly, Criminology has always been around, but never had the opportunity to become its own thing. While the main focus of Criminology is to study and recommend solutions for the causation of crime, it is also responsible for defining what a crime is. While it is true that laws have been passed throughout history, it can be argued that those laws were a byproduct of Criminological thinking. And those individuals responsible for creating the laws that define our individual and social behaviors in some form or fashion used a type of Criminological process to create those very laws we live by (and break) even today. Early lawmakers certainly had to determine what behaviors were acceptable and which ones were not, and in that determination they would have had to conceptualize those behaviors.

Criminology as an academic discipline, however, was the product of something new–the scientific revolution. Science provided a powerful tool for understanding the nature of criminal behaviour and new methods for studying crime in society. However, it also encouraged the view that the distinct ways Europeans thought about crime were universal and objective, rather than the ideas of people living in a particular place and time.

We can see the Eurocentric nature of these views in the way criminologists applied the new idea of evolution during the classical period. Early European criminologists, including the followers of Cesare Lombroso, believed crime was something rooted in our evolution, or more specifically, in the failure of criminals to develop adaptive traits like empathy and honesty (Garofalo, 1914). The Lombrosians saw crime as something abnormal–something that could be tracked down and rooted out, with the help of criminologists, of course. By identifying and eliminating enough criminals, these pioneering criminologists believed we might be able to get rid of crime altogether.

This biological approach provided a new way for thinking about crime, yet critics were quick to point out that the Lombrosians misunderstood both the roots of criminal activity (i.e., why people engage in criminalized behaviour) and its function (i.e., what crime does for society) (De Cleyre, 2020; Durkheim, 1982; Tarde, 1886). The French sociologist Émile Durkheim was one such critic (see chapter 5 Social Disorganization and Differential Association). He argued that crime in fact is a normal part of every society and something that can never really be eliminated (Durkheim, 1982). He also tells us that crime performs an important function for society in that it establishes the norms for what is acceptable behaviour. Durkheim recognised that all societies develop their own moral boundaries and that the resultant norms are important for both personal and social well-being.

Legalistic and Conflict Perspectives

While crime is a universal social phenomenon, what counts as crime is particular to each society. What makes something a crime for Durkheim (1933) is that it “offends certain collective feelings which are especially strong” (p. 99). Crimes are not, however, just anything that offends a person’s sense of proper behaviour. Crime represents a form of deviance that calls forth a strong reaction from society; a reaction that can include a punishment or other forms of social censure. Understanding crime in this way helps us avoid some of the mistakes people make when they think of crime as something that can be permanently eliminated from a society, like impurities from water.

Acknowledging crime as normal is not the same as saying it is good. Nor does this view indicate why a particular person might commit a crime (e.g., it could well be the psychology of the individual). Understanding crime as normal means that what comes to be seen as crime is a product of the society in question, rather than something that resides within an individual; in that regard, it constitutes a normal part of social dynamics.

If crime is the product of a society’s moral boundaries, how are we to understand crime in a complex, multicultural settler-state like Louisiana? Specifically, how can we understand crime in a place where significant differences exist between settler and Indigenous understandings regarding how to best respond to it?

Crimes are transgressions that violate the laws a society holds dear. These laws may be formally written down, held by knowledge keepers, or commonly known to all members of the group. To commit a crime is to break the rules a society views as the moral limits of acceptable behaviour. Crimes are an offence against society, not just an individual. Louisiana criminal law is mainly codified by the Louisiana State Legislature which sets out the various offenses a person might commit and the range of punishments that they might receive. Criminal lawyers in Louisiana define crime largely in relation to these laws, and some criminologists (such as Edwin Sutherland, 1949) have argued that the criminological study of crime should be restricted to violations of state criminal codes. This view is known as a legalistic approach to crime because it focuses strictly on violations of the legal code.

Under Louisiana criminal law, a person may be charged with two main types of criminal offenses: misdemeanors and felonies. A misdemeanor offence is the less serious of the two and therefore carries a lesser punishment. An example of a misdemeanor offence is causing a disturbance or theft under $5,000. More serious offenses in Louisiana are known as felonies. These include crimes such as murder or assault and can carry stiffer penalties, including life in prison.

In legal terms, to be found guilty of a criminal offence in Louisiana, a person must have committed a guilty act (i.e., actus reus) and be of a guilty frame of mind at the time of the offence (i.e., mens rea). It is not enough that a person commits an act that contravenes state law; they must also be of a certain state of mind, such as intending to commit the act or behaving with recklessness, negligence, or being willfully blind to the outcome (McElman, 2000).

For many offenses, the state of mind and the action naturally occur together. Someone might want an item that belongs to another person (e.g., a car) and takes that object without having the right. The person, therefore, violated the law and intended to do so to satisfy their desire. In some cases, however, the lines are not so clear, such as when someone is sold a stolen car without knowing the car was stolen. Furthermore, some people, such as young children and people suffering from certain forms of mental illness, are thought to not possess the frame of mind necessary for mens rea and therefore may receive treatment rather than punishment for their actions.

Codified laws are no doubt important for understanding what crime is and they can be found as far back as 4000 years ago, with the codes of Ur-Nammu and Hammurabi (see Figures 1 and 2) representing some of the oldest surviving examples of codified laws (Fairlie, 2019). Thinking of crime in terms of the violation of codified laws is useful as it provides an objective standard for knowing crime when we see it. Reported crime rates, such as those generated by the Uniform Crime Reporting Program, capture this legalistic definition of crime, and treat crime as something real that can be classified and counted.

We need to be careful, however, about limiting our understanding of crime to a set of codified rules. For one, it is likely that many of the earliest known legal codes, such as the codes of Ur-Nammu and Hammurabi (see Figures 1.1 and 1.2), were more akin to visions of stately order (i.e., the way the rulers would like things to be) rather than codes used for adjudicating cases (i.e., the practical settling of disputes). In early history, the latter would likely be determined according to local custom rather than the rules set by a distant ruler (Pririe, 2021). Of course, once the rules are set down in stone (quite literally in some cases), they can be used by the weak to press claims against the strong. This is what we mean when we talk about the rule of law; it applies to all.

Thinking about written law as visions of stately order is useful for understanding the role it has played in the expansion of colonialism in Louisiana. Indigenous and migrant peoples were subjected to laws they often had no knowledge of while continuing to deal with crime in their own communities using local systems well after the territories were claimed by European colonists. Was the function of law in such cases to solve local disputes? Or was it more like the stately visions of ancient rulers?

While a legalistic approach to crime (i.e., one based on codified laws) is important, many contemporary criminologists find this way of thinking about crime problematic in that it limits our ability to engage with the subject of crime in a critical way (Quinney & Wildeman, 1991). Law is an historical and cultural product; that is to say, it is a social construct. Legalism, however, encourages us to think of crime in a reified way–as a “thing-in-itself”–rather than in terms of its social nature. While some laws do emerge from consensus (with all or most members of a group feeling the same way), the conflict perspective proposes that laws may serve the interests of one group over those of another.

The significance of the conflict perspective can be seen in the case of the Slave Act of 1824, a piece of Louisiana legislation that clearly serves the interests of slaveholders over those of enslaved people. Article 177 of the Slave Act made it illegal for a slave to be a participant in any legal matter unless specifically provisioned by law (Louisiana Civil Code , 1824). While it might be interesting to know how many people were charged for violating this law, the figure would hardly seem sufficient for understanding the position of law within the context of master-slave relations, or for getting at the issue of why enslaved peoples were being denied legal representation in the first place.

As the example above also demonstrates, a limit imposed by a purely legalistic understanding of crime is that it gives the dominant group the power to define what constitutes crime and, by extension, the scope of criminology as an academic discipline (Quinney, The Social Reality of Crime, 1970). Criminologists have recognized this problem for decades, particularly in the case of corporate crime (Chamblis, 2001), where corporations have the power to lobby governments to change laws in their favour, and crimes related to the environment, where we see laws being changed to allow corporations to threaten the flow of rivers (Graveline, 2012) (see chapters 6 and 7 ). Therefore, we should recognise that the term crime is not limited to criminal law, and that thinking about “crime” broadly in terms of harm and injustice continues to shape contemporary discussions around human (and non-human) rights.

A legalistic approach to defining crime risks privileging the perspective of the state over that of society. It also fails to adequately capture the power dynamics at play when the law is applied unevenly, as is frequently the case for Black, Indigenous, and People of Color living in states like Louisiana (American Civil Liberties Union). The focus remains instead on the criminalized individual, rather than why the rule exists or the effects that being labeled a “criminal” might have on a person or entire group of people.

Some criminologists have therefore advocated for the need to decriminalize criminology by expanding the scope of study to include a broader range of harms, such as racism, sexism, classism, and ableism (Shearing, 1989). Focusing on harm, rather than the letter of the law, allows us to understand the process through which some harms are criminalized while other social harms remain unaddressed (Ferguson, 2020).

A key social institution that constructs our idea of what crime is today is the media (Surette, 2011). The media is effective in amplifying particular threats, sometimes to the point of generating moral panics and constructing representations of groups (e.g., youth, the working class, and racialized communities) as posing a threat to public well-being. As the media is largely privately owned, crimes of the upper classes (e.g., insider trading, fraud, and environmental crimes) are often filtered out. The media also plays a role in establishing a distance between “us” and “them” through a process of Othering, in which criminals are depicted as fundamentally different from the rest of the population and therefore deserving, if not requiring, incarceration.

How Crime and Criminology Affect Life in Louisiana

Crime is everywhere, let’s face it. In some communities, crime has become the normal function of life. Everyone has to deal with crime in some or fashion, whether they are victim, perpetrator, or witness. And no specific entity has the cure for the problem of crime. Some policymakers advocate for harsher punishment. Some push for more holistic approaches (Mental Health Treatments, Pre-incarceration Diversion Programs, Probation and Parole, Community Activism, etc.). The issue is not with developing alternative solutions to an old problem, the issue comes from the inability of those in power to invest in those alternative solutions, for whatever reasons they may be.

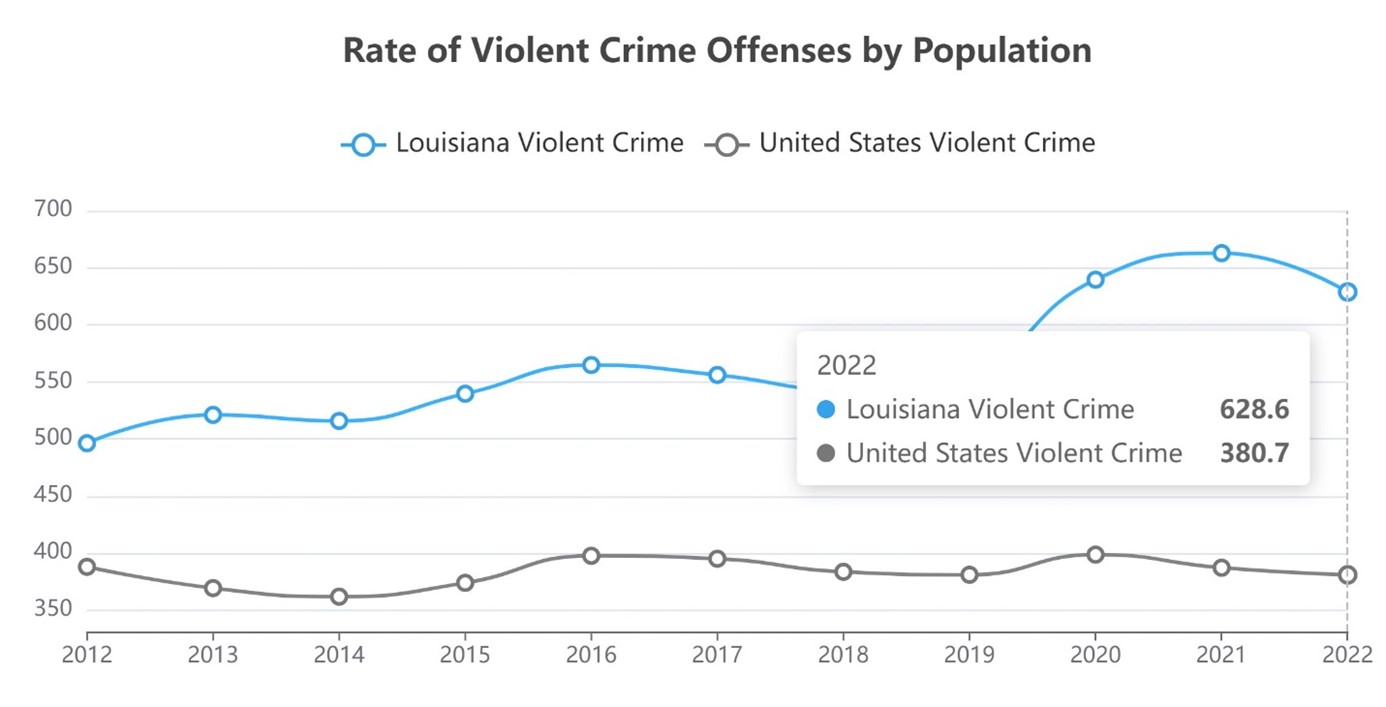

Crime in Louisiana is no different. According to data from the UCR, in 2022 the average crime rate in Louisiana was 628.6 instances per 100,000 people (UCR, 2024). Compared to the national average of 380.7 instances per 100,000 people, Louisianans have a higher chance of being victims of a crime than almost anyone else in the United States (see Figure 1.3).

Throughout this textbook, you will see crime approached in both a legalistic way and as a social construction (Berger & Luckmann, 1966). These two views are not mutually exclusive. Criminal law itself is a social construct, and the process of creating crime and criminals is dependent on law for its legitimation. But as you will see, the two ways of thinking about crime (i.e., legalistic vs. social constructionist) come into play in different ways depending on the topic or theory you are learning. If you can hold this tension in mind while you read this book, you will be well on your way to thinking like a criminologist.

Critical Thinking Discussion

Thinking about where you grew up, what was your experience with crime? Who were you influenced by in determining your own personal definition of crime? Take that experience and apply it to an environment that could be different from your own. How do they compare/contrast? How similar/different are they in scope?

The intentional commission of an act usually deemed socially harmful or dangerous and specifically defined, prohibited, and punishable under criminal law.

The scientific study of crime causation.

The system of rules which a particular country or community recognizes as regulating the actions of its members and which it may enforce by the imposition of penalties.

An act that is in violation of established law.

A criminal offense that is less serious than a felony and is punishable by a fine and/or a jail term of up to one year.

Crimes that are punishable by more severe penalties than misdemeanors.

Action or conduct which is a constituent element of a crime, as opposed to the mental state of the accused.

The intention or knowledge of wrongdoing that constitutes part of a crime, as opposed to the action or conduct of the accused.

A concept or idea that is created and accepted by a society, and is not based on objective reality

a general agreement, or an idea or opinion that is shared by most people in a group.

views crime as a result of social conflict and the unequal distribution of power and wealth in society.