5 Chapter 2 – Classical Theories of Criminology

Brandon Hamann

Learning Objectives

This chapter introduces the Conceptualization of Crime, the Classical School of Criminology, as well as the individuals who are responsible for the formulation and implementation of those theories into the study of crime causation. After reading this chapter, the student will be able to:

- Identify the theorists responsible for the creation of the first theories of crime causation.

- Differentiate the various conceptualizations and typologies of crime.

- Recognize the impact of the Classical School of Criminology on policymaking in the state of Louisiana.

Introduction

The first Criminologists weren’t Criminologists. They were politicians, activists, economists, doctors, and philosophers. Likewise, there is no definitive answer of who can be a Criminologist. While Criminologists are tasked with trying to understand the influences that motivate individuals and/or groups to commit criminal acts, their backgrounds are as varied as the types of crimes that are out there. Furthermore, Criminologists should be knowledgeable in a number of other fields of study (Political Science, Economics, Religion, Biological Sciences, Law, etc.) because crime causation is affected by more than just the realm encompassed by the study of Criminology. In fact, Criminologists should “know a little bit about a little bit” when attempting to develop a theory or make a recommendation on a policy shift regarding the remediation of criminal activity in a community.

Criminologists are Doctors, Lawyers, Teachers, Social Workers, Police Officers, Journalists, Psychologists, and anyone else who is interested in the study of crime causation. All that is needed is a keen eye for detail, a passion for research, and an insatiable need to answer tough questions objectively regarding crime.

The Conceptualization of Crime

Crime can be theorized in several ways. The most common way people view crime is as harmful acts that are “against the law.” However, many criminologists take a more complex view of the matter and caution that it is unwise to simply see crime as a violation of the law (Beirne & Messerschmidt, 2011; Agnew, 2011). As explained in Chapter 1, the law is technically a social construction, and many acts that cause significant harm are legal while other acts that cause minimal harm are criminalised. If criminologists only focus on acts that are violations of criminal law, they miss harms that fall outside of the law, and risk viewing relatively harmless behavior as a problem simply because it is illegal.

To address these gaps, some criminologists suggest that we view crime as a violation of conduct norms (Sellin, 1938) (see chapter 5 Social Disorganization and Differential Association). In other words, it is important to consider what a culture or group deems to be normal or deviant behavior as this may vary based on geographic location, history, and a variety of other factors. Deviance refers to behaviors that depart from or violates social norms. These behaviors are not necessarily deviant and may not even be criminalized, but these acts may be criminalized in the future due to cultural changes. For example, adultery (or “cheating on someone”) is considered a deviant act in cultures where monogamy is the norm, but it is rarely criminalized. Thinking about the relationship between crime and deviance can shed light on why some acts were criminalized in the first place. We can see, then, that the definitions of crime and deviance change over time and differ from culture to culture. In an effort to apply a more systematic and objective (i.e., “scientific”) approach to the study of crime, criminologists have developed typologies and other classification systems to organize their thinking about criminal acts.

Crime Typologies

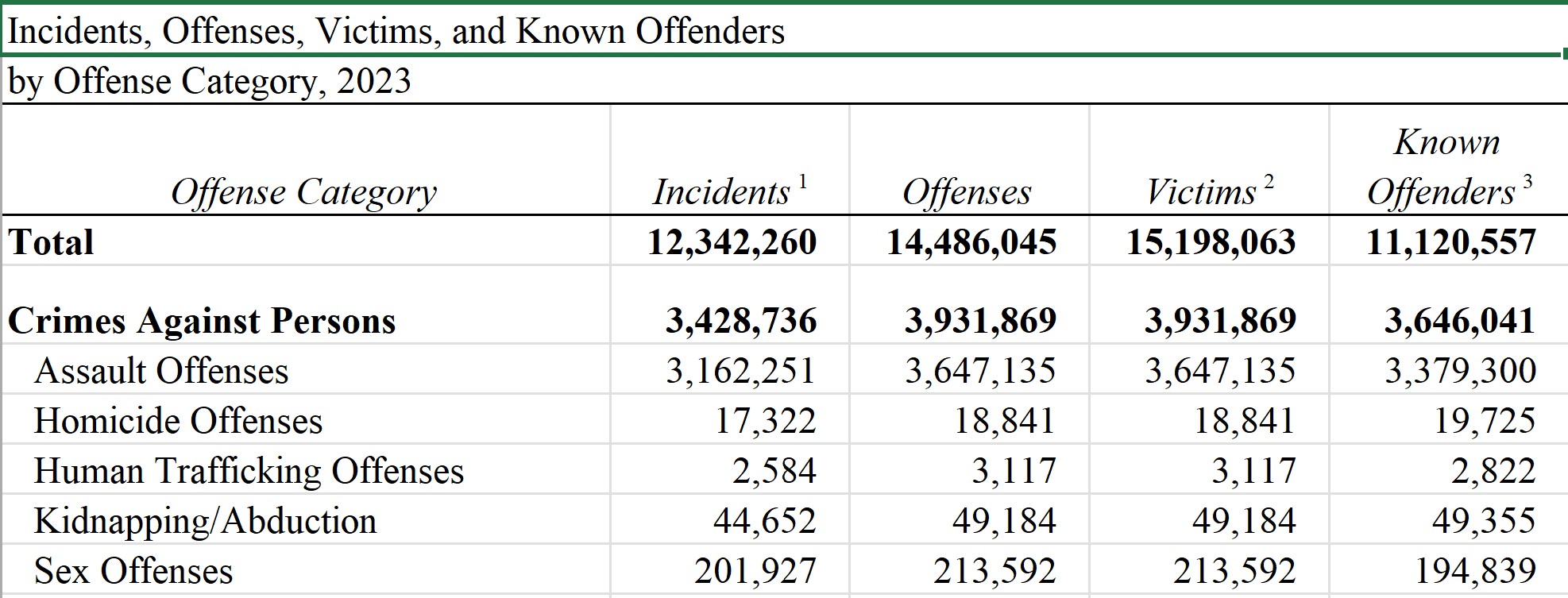

The Uniform Crime Report (UCR) (discussed in greater length in the Scientific and Empirical Research chapter of this text) has a typology, or special system for classifying different types of crime: violent crime, property crime, other crime, traffic offences, federal drug offences, and other federal law violations. Another common approach is to divide criminal acts into victimless crimes (e.g., drug use, prostitution, and illegal gambling) and crimes where there is a clear victim (e.g., robberies and physical assaults). Alternatively, criminologists and other commentators may use the categories of street crime or blue-collar crime (e.g., more common types of property and minor violent crime) and suite crime or white-collar crime (e.g., financial, and occupational forms of crime committed by those with status or power in society, such as politicians, legal officials, corporate executives, celebrities, and famous athletes).

While these classification systems are clearly useful, most typologies fail to capture all types of crime and conceptualize them in a way that is helpful to students new to criminology. To address these concerns, this reading will review crimes that receive the most attention from criminologists. We will use the following system of classification:

Violent crime: homicide, sexual assault, assault, and robbery.

Property crime: breaking and entering, theft, identity fraud, and identity theft.

Crimes of morality/public order: drug use and prostitution.

Organized crime: serious crimes committed by groups of at least three people with the underlying purpose of reaping material or financial benefits.

Hate crime and terrorism

White-collar crime: crimes committed by a person of respectability and high social status in the course of their occupation for their own benefit.

Corporate crime: crimes committed by a person of respectability and high social status in the course of their occupation for the benefit of their business or corporation.

The following section will review the definitions of the types of crime listed above (with the exception of white-collar and corporate crime, which are discussed in chapter 6 Anomie and Strain Theory) and the ways they are considered to have different levels of severity. In addition, some observations will be made about the situations in which these types of crimes occur and any patterns that can be identified.

Criminology and the Classical School

The field of Criminology is broken up into “Schools.” These schools represent an evolutionary progression of the study of crime causation based on historical events of the times in which those theories were first established. As mentioned in Chapter 1, Criminology as a field is relatively young compared to other sciences (both Social and Biological). Criminology is at its core a derivation of the study of Sociology but branched off to become its own field of study somewhere in the late 18th century. The theorists of this time were concerned with the systems of justice in their respective communities and their influences on crime and punishment.

Before this, however, citizens began to question the justification of their governments and of the affects the criminal justice system had on their daily lives (Fedorek, 2019). Historically speaking, this began towards the end of the Middle Ages (500 to 1500 AD). A renaissance of social thinking argued that the monarchies of the era were too heavy-handed in their interpretation and implementation of justice within its constabulary and not paying close enough attention to the negative effects on the citizenry experienced by cruel and unusual punishment practices. Governments during these periods were never truly representative of the communities in which they governed, mostly because the power laid with the wealthy and powerful landowners and the royalty of the ruling class. The people had no right to confront their accusers, and the rich and powerful used this to their advantage. This inequity would be the birth of the social disruptors who would become the first Criminologists.

The Classical School of Criminology

The Classical School of Criminology is focused on the idea that people prioritize their personal well-being through their ability to rationally choose between good behavior and bad behavior. Early theorists argued that people chose to pursue a state of pleasure over a state of pain and did so with the explicit need for self-gratification. The first theorists also argued that people were entitled to certain inalienable rights, a just criminal justice system for all, and the ability to have a coexisting relationship with that system.

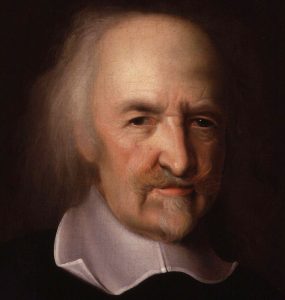

Thomas Hobbes

In the mid-17th century Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679), a British philosopher, wrote in his seminal piece Leviathan (1651) that people were rational and were entitled to such things as life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness as well as the right to self-government. In the case of punishment, according to Hobbes (1651), judges were not bound by another’s sentencing prescription simply because there was precedence to do so. This social contract thinking would later be a building block for the modern American Criminal Justice System.

Hobbes’s Social Contract Theory is especially influential to the early concepts of Criminology, in that it suggests that humans naturally gravitate towards a system that is beneficial to their individual needs. Humans are possessed by a need for self-interest and will develop mechanisms within their experience to elevate their own social perspective. Hobbes argues that any term that expresses a positive or negative outcome is not born from emotion, but rather a need to separate what is beneficial and what is not from a micro social and a macro societal perspective. More explicitly, humans individually develop those systems that benefit them and transmit those systems to an aggregate (We take what makes us happy and project that on a larger scale to include everyone around us).

And we do this because we are reasonable in our thinking and our actions. Or are we?

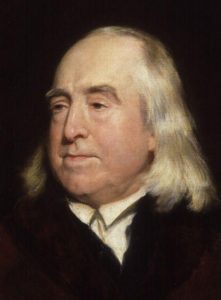

Sir Jeremy Bentham

Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832) was a British philosopher and reformer whose ideas about crime and punishment have influenced many criminological theories. His contribution to the field of Criminology centered around the concept of Utilitarianism, the belief that people act in their own self-interest. Bentham also considered the average person to be hedonistic, acting in such a manner that maximized their personal thirst for pleasure, while limiting their experience with pain. How these terms (pleasure and pain) were defined was subjective to the encounter in which they were experienced. We think of pleasure and pain in terms of emotional gratification. Bentham thought of pleasure and pain in a more inclusive manner: psychological, economical, and social. To further justify this course of behavior, Bentham argued that lawmakers should be in tune with the personal needs of citizens and devote their time to producing policies that focused on their need to be happy. Again, how that happiness was defined was never universally accepted.

In the event that pain was necessary as a means of punishment, Sir Jeremy Bentham had posited a concept that would later be influential in the theory of Deterrence. He argued that punishment should be used as a means of last resort, in such a manner that was quick and just harsh enough to sway the opinion of the masses into understanding that a particular behavior that was deemed deviant was not worth the suffering it incurred. During the 18th and 19th centuries, it was not uncommon for criminals to be punished in plain view of the public, in an attempt to influence behavior against a particular act that was considered unlawful.

Sir Jeremy Bentham also expounded on the Social Contract Theory of Thomas Hobbes, going so far as to describe the process in which humans made decisions regarding their personal behavior. He reasoned that not only are people reasonable, but also rational in their choices, basing their behavior on a cost/benefit analysis. To Bentham, the choice to commit an act of deviance was directly influenced by the level of reward associated with the risk, and if the benefit of the “crime” outweighed the cost, then a rational person would more than likely engage in that behavior. This conceptualization would later evolve into Rational Choice Theory (see Chapter 7 Control, Rational Choice, and Routine Activities Theories), but the foundation was laid here.

Cesare Beccaria

One of the first “Criminologists” wasn’t even one. Cesare Beccaria (1738-1794), an Italian philosopher, economist, and politician, is considered to be the “Father of Criminology.” He authored a book titled An Essay on Crimes and Punishment in 1764 which laid the foundation for what came to be called the Classical School of Criminological Theory. In the book, Beccaria theorized that crime occurs when the benefits outweigh the costs—when people pursue self-interest in the absence of effective punishments, and that crime is a free-willed, rational choice. Beccaria also revised the concept of proportionality, first introduced by Sir Jeremy Bentham, which states that in order for a punishment to be effective, it must fit the crime that it is intended to deter from repeating (di Beccaria & Voltaire, 1872).

Personal Statement

Brandon Hamann – Dillard University

Hobbes argued that humans made decisions because they were reasonable. In so doing, he laid the groundwork for the concept of Free Will – the innate ability for humankind to think for themselves regardless of outside influences… or maybe because of them.

Bentham theorized that humans were hedonistic in nature – they prioritized pleasure over pain. How those terms were defined depended on the situation.

Beccaria said that proportionality was paramount in any justice system because the punishment for a crime had to be commensurate with the level of the crime that was committed.

Thinking back on my life, I can certainly understand these concepts, especially when it came to how I viewed certain situations. We are all a victim of our own self-interests. More often than not we make decisions that purely benefit our own selfish needs, regardless of the impact they may have on others, or ourselves. And in doing so, we also justify those decisions in a manner that suits our individual needs (I need to do this because I need to…).

But there is a fine line where “need” becomes “want.” In the world of Criminology, crime causation has many theoretical explanations within its respected Schools. For this chapter, it’s the difference between “need” and “want” that is the most prescient. And we can correlate these causation devices to our own personal life experiences whether we are consciously aware of them or not.

In my experience with the Criminal Justice System, I can most definitely differentiate between the two. Remember in Chapter 1, my Personal Statement gave a brief synopsis of my own criminal activity from an early age. I knew what I was doing was wrong, but I did it anyway because I wanted to, because I needed to. I wanted to be a part of the group. I needed to be a part of the group. There were no other kids my own age in the area, and if I wanted to have friends, I needed to be a part of the group. And we were tight-knit, looking out for each other everywhere we went, and doing whatever it took to take care of each other.

As we got older, into our teens and 20s, our criminal activity began to evolve. Instead of stealing from convenience stores, we graduated to more illicit activities. It was during the 1990s that we reached our peak of criminal influence, and subsequently saw it all come crashing down.

We started innocently enough with recreational drugs. The drinking age at the time was still 18, so we would hit all the bars in town and quickly built a reputation among the social crowd. We were having fun, getting high and drunk, making a bit of money on the side, and not worrying about any of the consequences. In our hubris, we thought we were invulnerable because everyone we were dealing with were our friends… or so we thought. As our bubble of influence grew, so did the probability of us gaining the attention of Law Enforcement. And that’s exactly what happened. We had, unbeknownst to us, been under surveillance for quite some time and eventually were caught.

As I sat in the holding cell awaiting my fate, I kept thinking to myself, “What am I doing? I know better. I was raised better than this. Is this how I want to spend the rest of my life?” It was at that seminal moment that I realized the course I was taking was not in my own self-interest – the pleasure I was seeking was actually causing pain, for myself and my family. I needed to make a change, and quickly before it was too late.

I was one of the lucky ones. I was fortunate enough that my parents were able to use their house as collateral to post my bail. I was fortunate enough that my parents were able to afford a decent attorney. And I was darn sure fortunate enough that the judge dropped the charges against me. The District Attorney had sought a sentence of 10 years with hard labor at Angola State Penitentiary. Angola is where they house the most violent criminals: murderers, rapists, child molesters, etc. It could be argued that the punishment was not proportionate to the crime, but I digress.

It was a shock to the system that definitely challenged my sense of hedonism, rational and reasonable choice, and deterred me from ever committing another act of deviance. My son is now a Law Enforcement Officer, and we have had many conversations regarding crime causation. He is well aware of my previous circumstances, and he understands that sometimes people do things that they believe is in their best interest, but that those justifications are hardly ever worth the cost.

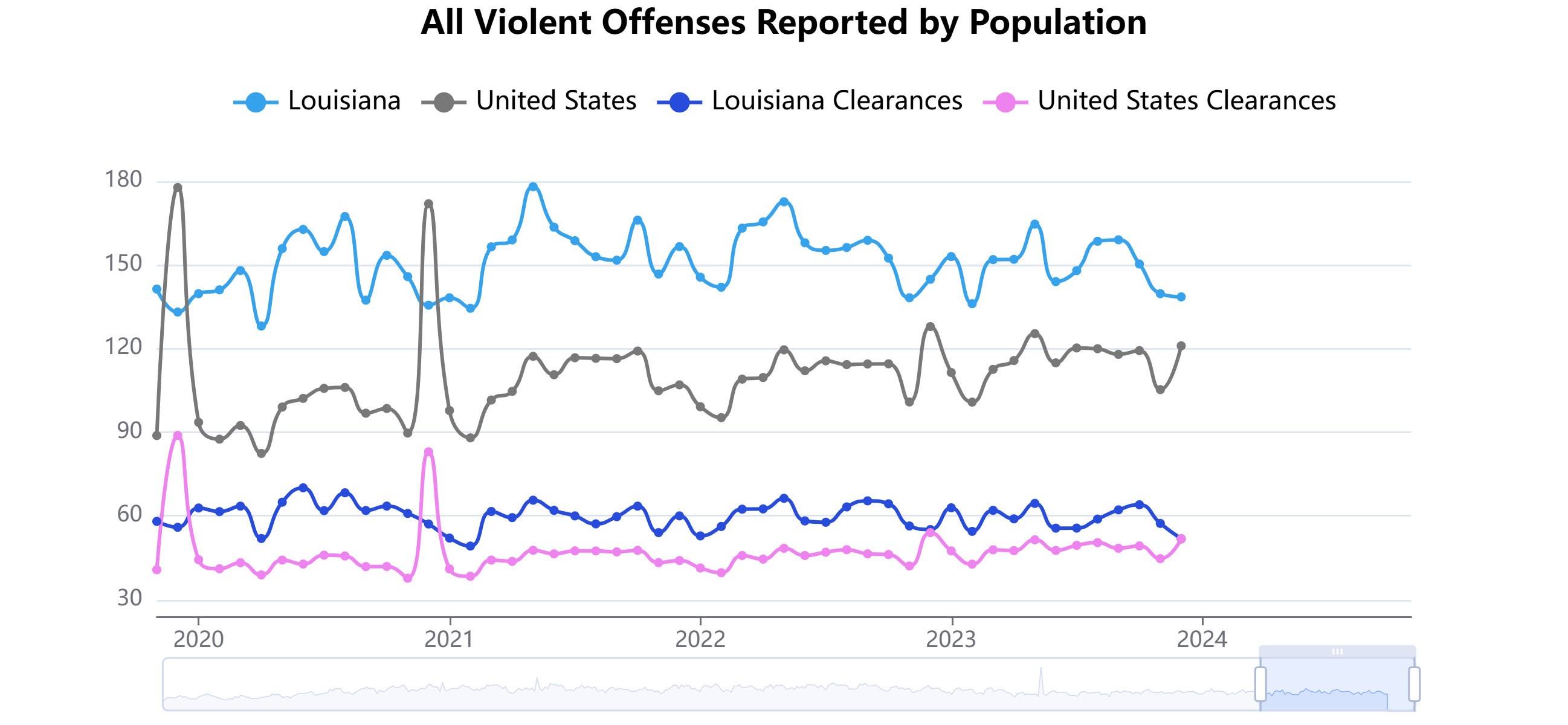

How The Classical School of Criminology Affects Life in Louisiana

It doesn’t take a genius to realize that the concepts of crime causation introduced in this chapter all have some influence on our everyday lives. We all go about our days with the notion that every decision we make is in our own best interest. It doesn’t matter if those decisions involve what we buy at the grocery store, or how much cereal we eat for breakfast (or dinner, if that’s your game). And to consciously be aware of the consequences of all our actions throughout our lives is something we take for granted. Criminology is a fascinating field of study in that it not only gives us a better understanding of the mechanisms that go into trying to explain criminal behavior, it also gives us an opportunity to explore so many other areas of influence in our lives and how they equally affect our non-criminal behavior.

People are hedonists, whether they know what it means or not. And that is not necessarily a bad thing. Where it becomes problematic is when that sense of self-interest misaligns with the majority of what the community considers acceptable social behavior. That is the reason for laws: social behavior control. And it isn’t just laws that directly influence our behavior, but also those values learned through our own life experience. We are influenced by our parents, our elders, our religious institutions, our schools, and our own sense of morality when it comes to proper behavior norms. If those boundaries are not learned early in life, can we honestly expect that a person will behave in a fashion that we consider acceptable?

The Classical School of Criminology is the foundation of crime causation. The theories developed within gives us, Criminologists and non-Criminologists alike, a glimpse into the building blocks of deviant behavior, but it also gives us an opportunity to understand behavior as a whole. This is where we can begin to differentiate between the “need” and the “want.” If we as Criminologists can understand and pinpoint events that can be used to influence policy in such a manner that alleviates the need or want to commit an act of crime, then we must endeavor to pursue that course of reasoning.

Critical Thinking Discussion

From what you have learned from the reading and the videos, can you relate to any of the concepts introduced in this chapter? Do you believe that humans make decisions in a reasonable or rational manner? If so, how? Do you believe that humans are prone to being more interested in their own situations rather than pondering on the consequences of those actions? And finally, can you think of a situation in which a punishment could be justified to not be proportionate with the crime that was committed?

behaviors that depart from or violates social norms.

A special system for classifying different types of crime.

homicide, sexual assault, assault, and robbery

breaking and entering, theft, identity fraud, and identity theft

drug use and prostitution

serious crimes committed by groups of at least three people with the underlying purpose of reaping material or financial benefits

a crime, typically one involving violence, that is motivated by prejudice on the basis of ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation, or similar grounds.

the unlawful use of violence and intimidation, especially against civilians, in the pursuit of political aims.

crimes committed by a person of respectability and high social status in the course of their occupation for their own benefit.

crimes committed by a person of respectability and high social status in the course of their occupation for the benefit of their business or corporation.

people were rational and were entitled to such things as life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness as well as the right to self-government.

the belief that people act in their own self-interest.

to live in a way that prioritizes pleasure over other values.

crime can be prevented by using swift, certain, and proportionate punishments.

Father of Criminology.

a theory of crime that originated during the Enlightenment and is based on the idea that people are rational and have free will.

in order for a punishment to be effective, it must fit the crime that it is intended to deter from repeating.