41 Chapter 11 – Integrated Theory

Jasmine Wise

Learning Objectives

This chapter introduces Integrated Theory

- Identify origins of integrated theory

- Explain sources of integrated theory

- Apply integrated theory to real world situations

Jason is a 16-year-old boy living in an economically disadvantaged neighborhood with his mother, who works long hours and has limited time to supervise him. At school, Jason struggles academically and often feels discouraged because, despite trying, he cannot achieve the same success as others. He becomes increasingly frustrated that his family cannot afford the clothes, gadgets, and lifestyle that many of his classmates have. Over time, this sense of unfairness and failure causes Jason to feel disconnected from school and unmotivated to continue following the rules.

As Jason spends less time at home and school, he begins hanging out with a group of older boys in the neighborhood. They often skip school and engage in petty crimes, such as shoplifting and selling stolen items for quick money. Jason starts joining them and quickly realises that this behaviour earns him both material rewards and acceptance from the group. The boys praise him when he participates, which encourages him to continue. With little guidance at home and no strong involvement in positive activities, Jason becomes more influenced by his peers and less connected to conventional values. Before long, minor offending becomes part of his daily routine.

Jason’s experiences can be examined using an integrated criminological approach. His situation involves several factors: the pressure and frustration he feels from limited legitimate opportunities, the influence of peers who model and reward rule-breaking behaviour, and the absence of strong family or school bonds that could discourage offending. Together, these factors interact and shape his pathway into delinquency.

The first element of Jason’s story relates to Strain Theory, which suggests that when individuals face blocked opportunities or inequality, they may turn to deviant behavior to achieve their goals or relieve frustration. His peer involvement reflects Social Learning Theory, as Jason learns criminal behavior through association, imitation, and reinforcement from his friends. Finally, Control Theory helps explain why Jason continued offending, as his weak attachment to family, low commitment to school, and lack of involvement in pro-social activities reduced the social controls that might have prevented his delinquency. When combined, these theories provide a fuller understanding of Jason’s behaviour than any single theory could offer.

Introduction

Throughout this book we have looked at the various theories behind why someone would commit a crime. In this chapter, we will explore how the work together to explain criminality of individuals. In some cases there is more than one explanation to why they commit the crimes they commit. There is no one theory that can fully explain their actions. Integrated theory is an attempt to give more breath and depth to criminology.

Theories under the umbrellas of individual psychology emphasize personality, cognitive fallacies, psychopathology, and brain structure. Evolutionary psychology looks at ancient survival pressures and their impact on the human genome. Cultural psychology looks at how individual behavior is constructed by society. Social theories highlight the social environment of an individual and their propensity to commit crimes. Biopsychosocial criminology, on the other hand, is a multidisciplinary perspective that views criminal behavior by considering the interactions between biological, psychological, and sociological factors. This section describes three models that integrate theories from individual, evolutionary, and cultural approaches in their application to criminal behavior.

Personal Statement

Jasmine Wise- Northwestern State University

During my school years, I often felt pressure to meet high academic expectations. I believed that success was strongly connected to earning good grades, which sometimes caused stress and made me doubt myself. Although I didn’t respond in negative ways, I can understand how ongoing pressure might lead some young people to feel frustrated or discouraged, especially if they struggle to achieve what is expected of them.

I also recognize how much my behavior and attitudes were influenced by the people around me. At different times, I found myself copying certain behaviors from friends or classmates in order to fit in or feel accepted. These experiences showed me how easily individuals can learn both positive and negative habits through social interactions, and how peer influence can shape decisions, especially during school.

One of the main reasons I stayed focused on positive choices was the strong bond I had with my family. Their support, guidance, and involvement in my life helped keep me motivated and grounded. Having a family that cared about my well-being and future acted as protection, preventing me from being drawn into negative behavior. Looking back, I can see how the mix of academic pressure, learned behavior, and strong family support shaped my development, reflecting the ideas found in integrated criminological theory.

• Moffitt’s Developmental Taxonomy: explains the development of antisocial behavior as affected by biology, socialization, and stages of development.

• General Aggression Model: explains the biological, personality, cognitive, and social learning factors influencing an aggressive act.

• Risk Needs Responsivity Model: provides a method for offender assessment and treatment by examining the needs underlying criminal behavior.

• Trauma-Informed Systems of Care: combines the neurobiology of trauma with an analysis of the trauma-inducing aspects of the criminal justice system.

Developmental Taxonomy

The developmental taxonomy (Moffitt, 1993, 2018) describes two types of offenders differentiated by their biology, parenting, personality, and socialization: life-course-persistent offenders and adolescent-limited offenders. Life-course-persistent offenders are rare and have externalizing behavior from an early age continuing into adulthood. Neurological differences causing impulsivity and reactivity are believed to underlie their behavioral problems. Without intervention, difficulties with peers and school result, snowballing into later problems such as early school leaving and criminal activity. Early social rejection from peers is a major risk factor for later antisocial behavior (Cowan & Cowan, 2004), and these individuals often eventually associate together (Laird et al., 2009). Individuals following this life-course trajectory are considered the smallest group of offenders, but they are responsible for a disproportionate amount of crime (Piquero et al., 2012).

Conversely, adolescent-limited offenders engage in minor antisocial behavior during a developmentally normative stage in the teenage years but have an otherwise normal early childhood. Adolescent-limited offenders determine the benefits of a criminal lifestyle are not worth the risk, and they change in their early adulthood. According to the developmental taxonomy, these individuals are capable of easily changing because they have well-developed social and educational skills.

General Aggression Model

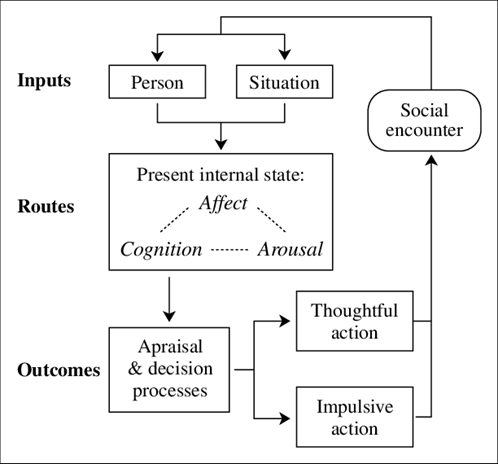

The general aggression model (GAM; DeWall et al., 2011) explains how various factors, including biology, personality, cognition, and social learning, work together to produce an aggressive incident. The GAM is structured in terms of responses to a situation: there are inputs (aspects of the person and situation) and outputs (results from decision-making that was either thoughtful or impulsive). Impulsive actions are more likely to be violent than thoughtful actions. Once violence is used by a person, the theory suggests that violence becomes a tactic more likely to be used again in the future, forming a behavioral pattern. Whether violence happens or does not happen in response to a situation depends on how the individual involved perceives and interprets the social interaction, their expectations of various outcomes, and their beliefs about the best ways to respond.

Ferguson and Dyck (2012) outline some assumptions made in the GAM, including the assumption that aggression is primarily learned. Ferguson and Dyck (2012) suggest that other factors, such as environmental stress, play a more important role in instigating aggression. In addition, they note that the GAM seems to explain hostile, reactive aggression without adequately explaining aggression that is calculated, goal-directed, and given forethought.

Risk Needs Responsivity Model

Two researchers, Don Andrews and James Bonta (2017), developed the risk needs responsivity (RNR) model for the assessment and treatment of offenders after many decades of researching the factors most related to criminal and violent behavior. Their model incorporates social learning, cognition, personality, and social factors. The RNR model has three main parts. First is the “risk” principle, which involves assessing offenders on the eight risk factors research indicates are most directly linked with criminal behavior. The intensity of treatment should match the level of risk, with individuals that score higher receiving more rehabilitation efforts. Criminogenic risk factors are outlined below:

- History of criminal behavior: How early crime starts, frequency and variability of criminal behavior

- Antisocial personality pattern: Having traits such as impulsivity, sensation-seeking, hostility, and callousness |

- Antisocial associates: Having friends that are involved in crime

- Antisocial attitudes: Having cognitions that rationalize antisocial behavior and/or disdain toward the law and justice system |

- Substance abuse: Misuse of alcohol and drugs

- Family/marital issues: For youth offenders, parents provide little warmth or control. For adult offenders, family/intimate relationships are unsupportive and/or with antisocial others

- Leisure: Few prosocial leisure activities

- Work/education: Poor performance and/or low satisfaction with work and/or school

Second, the “need” principle states that treatment should focus on addressing the needs associated with each risk factor found for the offender; factors the offender scores low on can be set aside in favor of rehabilitation focused on reducing the risk factors they score high on. Criminogenic needs are defined in response to eight risk factors; offenders scoring high on the work/education risk factor would be enrolled in alternative education or job retraining, while offenders scoring high in the antisocial attitudes risk factor would be referred to individual and/or group therapy.

Third, the “responsivity” principle states that treatment should be provided in a way that optimizes the offender’s successful response to the treatment. Treatment should be evidence-based but also implemented in a way that considers the individual’s learning style, motivation needs, and other characteristics that might impact treatment success.

The RNR approach has been criticized for being demotivating (Ward, 2002). Instead of RNR’s focus on risks, what is wrong, and what needs fixing, the good lives model (Ward & Gannon, 2006) suggests that a positive approach that addresses a person’s strengths, priorities, and ways to better their lives may be more effective. The good lives model assumes that all human beings are motivated by the same “primary goods,” such as relatedness, agency, and creativity. Offenders are attempting to attain these primary goods using inappropriate means and require new ways to obtain the primary goods they seek. The good lives model and RNR model focus on individual assessment and rehabilitation based on criminogenic needs and offender motivation, but the good lives model focuses on the offender’s goals instead of their deficits.

Models that rely on risk assessment use tools that have not been shown to be valid across cultures. Recently, an Indigenous offender successfully challenged the use of risk assessment tools in the Supreme Court, targeting the fairness and validity of making decisions about Indigenous offenders’ risk based on these tools (Ewert v. Canada, 2018). The failure to recognize biases in risk assessment adds to obstacles and overrepresentation already faced by Indigenous offenders (Forth & Book, 2017; Hart, 2016; Perley-Robertson et al., 2019; Wilson & Gutierrez, 2014). Rather than relying on risk factors that could unintentionally criminalize characteristics common to disadvantaged areas, such as low educational attainment, antisocial peers, and criminal history, Indigenous leaders suggest strength-based approaches rooted in culturally relevant social norms (Shepherd & Anthony, 2018).

Trauma-Informed Systems of Care

A trauma-informed approach draws on the interplay of neurobiology and adverse childhood experiences to explain the development of criminal behavior and offers approaches to law enforcement, mental health treatment, and rehabilitation that seek to avoid re-traumatization. Existing systems of care inadvertently contribute to the creation of toxic environments that interfere with mental health recovery and criminal rehabilitation. In the process, these systems undermine the well-being of police and mental health workers so that their own experiences of trauma on the job reduce their ability to effectively address criminal behavior.

Staff who work within a trauma-informed environment are taught to recognize how organizational practices may trigger painful memories and re-traumatize clients with trauma histories. For example, they recognize that using restraints on a person who has been sexually abused or placing a child who has been neglected and abandoned in a seclusion room may be re-traumatizing and interfere with healing and recovery.

A trauma-informed approach reflects adherence to six key principles rather than a prescribed set of practices or procedures. These principles, which are outlined below, may be generalizable across multiple types of settings, though their terminology and application may be setting- or sector-specific.

• Safety: Staff and the people they serve, whether children or adults, feel physically and psychologically safe.

• Trustworthiness and Transparency: Organizational operations and decisions are conducted with transparency with the goal of building and maintaining trust with clients and family members, among staff, and others involved in the organization.

• Peer Support: Peer support and mutual self-help are key vehicles for establishing safety and hope, building trust, enhancing collaboration, and utilizing personal stories and lived experience to promote recovery and healing.

• Collaboration and Mutuality: Importance is placed on leveling power differences between staff and clients and among organizational staff, from clerical and housekeeping personnel to professionals to administrators, promoting meaningful sharing of power and decision-making.

• Empowerment, Voice, and Choice: Throughout the organization and among the clients served, individuals’ strengths and experiences are recognized and built upon. The organization fosters a belief in resilience and in the ability of individuals, organizations, and communities to heal and promote recovery from trauma. Staff facilitate recovery rather than controlling recovery.

• Cultural, Historical, and Gender Issues: The organization actively moves past cultural stereotypes and biases; offers access to gender-responsive services; leverages the healing value of traditional cultural connections; incorporates policies, protocols, and processes that are responsive to the cultural needs of individuals served; and recognizes and addresses historical trauma.

Trauma-informed care recognizes the impact of historic events on present-day practices. The Truth and Reconciliation movement has brought new and needed attention to the multigenerational effects of colonialism on Indigenous peoples, which have led to many devastating impacts including substance abuse and domestic violence (Monchalin, 2016). Preliminary research indicates that incorporating culturally relevant programming for Indigenous offenders leads to higher completion rates and more effective treatment outcomes, including lower odds of recidivism (Gutierrez et al., 2018). Importantly, creating programs that are culturally relevant requires consulting and collaborating with Indigenous peoples and recognizing the diversity and needs within their communities.

Integrated Therooy in Louisiana

Louisiana Case Explained Using Integrated Theory

Case: Juvenile Carjacking in New Orleans

In recent years, New Orleans has faced a rise in juvenile carjackings, with several cases involving youths between 14–17 years old. One example involved a 15-year-old boy from Central City, New Orleans, who was arrested for participating in a series of carjackings with a small peer group. The teen lived in an area with high poverty, limited job opportunities, and under-resourced schools. He had been struggling academically, felt discouraged about his future, and believed he had little chance of success through legal means. This “blocked opportunity” contributed to his frustration—matching the ideas found in strain theory.

The teen was heavily influenced by older peers involved in car theft. He learned how to steal cars, disable tracking devices, and avoid police by watching others and joining them on “practice rides.” The group rewarded him with praise, protection, and a sense of belonging. This shows the role of social learning, where criminal behavior is learned and reinforced through peer relationships.

While the teen had a mother who cared for him, she worked multiple jobs and had limited time for supervision. He rarely attended school, had no involvement in sports or community programs, and had weak bonds with teachers or mentors. Because his connection to conventional institutions (school, family presence, positive activities) was weak, there were fewer social controls to keep him from offending—reflecting control theory. When these theories are combined, the case shows how poverty-based frustration, peer influence, and weak social bonds interacted to push the teen toward crime in New Orleans.

How Integrated Theory Explains Crime Patterns in Louisiana

Louisiana has one of the highest incarceration rates in the United States and experiences significant challenges related to youth crime, especially in major cities such as New Orleans, Baton Rouge, and Shreveport. An integrated theoretical approach helps explain this pattern more clearly than relying on a single theory. Strain theory is relevant because many communities face high poverty, limited access to quality education, and racial inequality. These conditions create pressure and frustration, especially for young people who see success portrayed online but lack equal access to legitimate opportunities. This can push some individuals to pursue alternative—and sometimes illegal—methods for achieving financial or social goals.

At the same time, social learning theory helps explain why certain types of crime, such as gang activity, drug trade, and car theft, spread among youth. In some Louisiana neighborhoods, crime becomes normalized because young people observe family members, neighbors, or peers involved in illegal activities. Social media has also influenced behavior by glamorizing criminal lifestyles, fast money, and violence. When young people see others rewarded with respect or financial gain for breaking the law, they are more likely to imitate it.

Finally, control theory shows how weak bonds with family, school, and community institutions increase the likelihood of crime. Louisiana struggles with underfunded schools, a lack of youth programs, and limited access to mental health and mentoring services, making it harder for young people to stay connected to positive social structures. When parental supervision is limited—often due to economic hardship—juveniles may form stronger bonds with peers on the streets than with conventional institutions. This combination of strain, learned behavior, and weakened social bonds helps explain Louisiana’s crime trends more fully than any single theory could.

What other cases can you use integrated theories to explain?

Critical Thinking Discussion

Do you think focusing on an offender’s strengths (as in the Good Lives Model) is more effective than focusing on their risks and deficits (as in the RNR Model)? Why or why not?

is a multidisciplinary perspective that views criminal behavior by considering the interactions

between biological, psychological, and sociological factors.

explains the development of antisocial behavior as

affected by biology, socialization, and stages of development

explains the biological, personality, cognitive and social learning factors influencing an aggressive act.

provides a method for offender assessment and

treatment by examining the needs underlying criminal behavior.

combines the neurobiology of trauma with an analysis

of the trauma-inducing aspects of the criminal justice system.