9 Chapter 3 – The Scientific Method and Empirical Research

Franklyn Scott

Learning Objectives

This chapter introduces students to the concepts of the Scientific Method and Empirical Research. After reading this chapter, students will be able to:

- Define the 9 steps of the Research Process

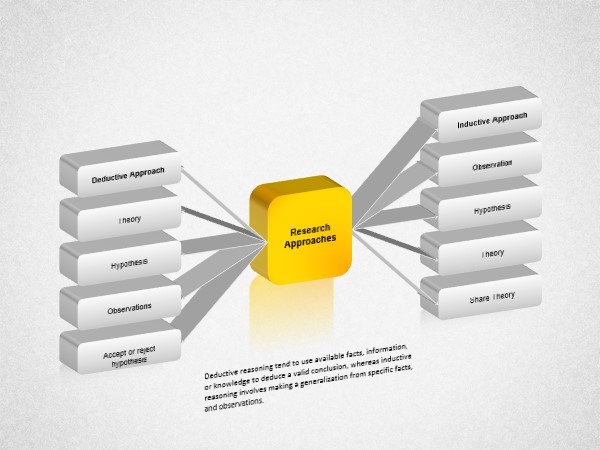

- Compare and contrast Inductive vs. Deductive Research, as well as Qualitative vs. Quantitative Research

The Scientific Method

Researchers and scientists utilized the systematic process of the scientific method to discern the facts within the environment (Anderson & Lin, 2024). Through observations, researchers develop questions to ask. Researchers produce hypotheses that are falsifiable and testable to respond to questions. Experiments are designed and performed by researchers with the primary purpose of finding the link between variables that are independent and dependent. Through experimental analysis of results, researchers can conclude if their hypotheses are sustained and if modifications are required for the experimental designs. Conclusions of the key takeaways drawn are provided to the scientific society. Through following the scientific method and the sharing of their results, researchers have expanded the scientific body of data.

The Research Process

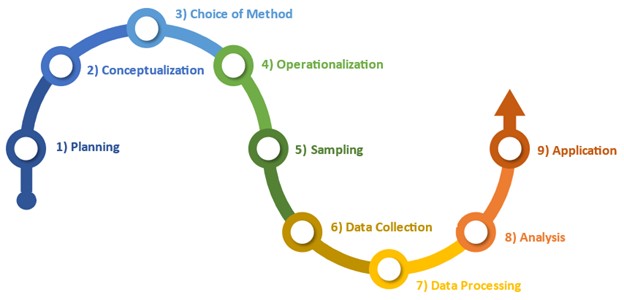

An understanding of quality research methods is fundamental to informed citizenship, scientific advancement, economic activity, and government decision-making. While research designs vary depending on a number of factors such as the topic being studied, the variables under consideration and the preferences and training of who is conducting the research, a basic Western research design is a good place to start in discussing research methods. In the subsections below, and as shown in Figure 3.1, each of the nine steps of this basic research process are outlined, beginning with Planning.

Planning

A key part of the planning stage is knowing what your objectives are. Are you trying to discover new information, or are you trying to find an answer to influence policy and programs? As you start to plan, you start to take a look at other studies on the topic. You look at the theory (or theories) referred to in those studies and the hypothesis they may have set out to test. You start to think about what your own research question(s) might be.

As part of the planning process, the research often starts with a topic and then a research question begins to form. As a researcher, what is a social question you would like the answer to or what is a social problem you would like to find possible solutions for? The research question specifies the variables to be studied and their relationship to each other. A variable is a person, place, thing, or phenomenon you are trying to measure in some way, and it varies (Bachman & Schutt, 2017). For example, age is a variable, as is income and socioeconomic status. A hypothesis is your informed thought or expectation of what the relationship is between variables, and it is often written as an “if, then” statement (Hagan, 2014). For example, one might hypothesise that “If the employment rate is low, then the property crime rate is high.” The hypothesis should clearly indicate the directionality of each variable, in this case, the employment rate and property crime (as one increases, the other decreases, or vice versa, or perhaps they both change in the same direction) as well as the temporal ordering of variables (low employment comes before high property crime). This “if, then” characteristic points to an essential element of a hypothesis: that it be testable.

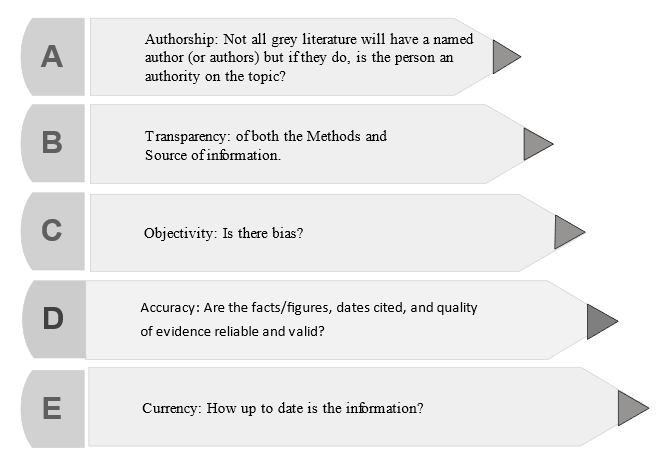

Beginning in the early planning stages, it is important for researchers to begin to understand and value Indigenous epistemologies and methodologies and to have an understanding of the basic scientific model. This blending of Indigenous worldviews and Western science is often referred to as Two-Eyed Seeing (Peltier, 2018). Cooperation between the researcher and the researched topic may lead to improvements in research methods and findings. One important step in this cooperative process is understanding first what the communities to be researched already know and have. This culturally relevant information can improve understanding between the researcher and the subjects, and it can provide a good context for research in these early planning stages. Collaboration with Indigenous knowledge holders and communities to co-design the study, co-frame the research questions, co-interpret results, and jointly co-create solutions is a much-needed improvement. Of course, for the research project to truly be joint, any grant or other funding obtained for the research should be shared. Research decisions and titles such as principal investigator, lead investigator or co-investigator as well as authorship on publication efforts and credit for work completed should also be shared. While forming our research question, we want to begin to examine existing literature about studies that have already been done on our topics. In addition to exploring the usual books and journal articles, we should work to avoid academic imperialism or only learning from big name authors in mainstream journals, by including grey literature in our preliminary research efforts. Grey literature is literature or evidence that is relevant to the research question but not published in typical commercial or academic peer-reviewed publications (See GreyNet International). Grey literature can include government and community reports, conference papers, dissertations, and other sources. Incorporating grey literature reduces publication bias and increases the comprehensiveness of any systematic literature review.

The researcher will need to evaluate the information as there may not have been a peer review process.

Let us turn to our two examples now and discuss how we might begin the planning for each. Using the cultural insights from the Indigenous community as well as the understanding from our initial review of the literature for our examples, we might start by stating that we want to examine financial exploitation by asking a set of closed-ended survey questions that have been used successfully in other financial exploitation research; this would be a deductive, quantitative approach to this research. We start to think about how we might later word the questions so they are culturally relevant, such as asking about “gifting” rather than “donations” and if money has been “missing” rather than “stolen” or “swindled.”

With our spirituality example, perhaps nothing appears in the typical literature, but we know that Indigenous cultures, and by extension Indigenous research, recognizes spirituality as an important contribution to ways of knowing. Western research ignores spirituality, which can cause tensions between research and its application in certain communities. For instance, perhaps elders told us during our meetings with them that the last group of researchers who studied the tribal people had concluded that Indigenous peoples were lazy and not concerned about their health because they did not use the gym that was built for them. What the researchers did not realise was that the facility was built on sacred ground, and the local people chose not to use it unless it was moved to a non-sacred space. Based on this informal but very important initial input from elders, we decide that what we should do is ask broad, open-ended questions about spirituality, whether elders are assisted in practicing their spirituality or if anything is keeping them from practising their spirituality. This is an inductive, qualitative approach to the study on spirituality; the approach emerged from the open-ended and open-minded line of questioning at the outset, which will be explained in more detail below in the section on choice of method.

Conceptualization

As you envision and start to become clearer on the key question(s) for your own research project, you are engaging in conceptualization and creating a mental picture of what your research methods will look like and what the concepts of interest are. You are very specific about what these concepts mean in your project. For example, if you want to study the fear of crime, what exactly do you mean by fear and what kind of crime are you referring to? Are you interested in whether people are afraid to walk alone at night, or are you interested in whether they are afraid that their identity will be stolen? You continue to review existing literature. This can help shape your image of your research project and identify what gaps exist in the literature, which you may choose to address in your own project.

As part of this second step, we need to create a mental picture of how we can find the answers to the research questions we have begun to develop and will now refine even further. Before exploring our research question through new research, we should continue to examine what research has already been done on this topic by others—both published and perhaps unpublished—and what theories or other ways of knowing, such as Indigenous ways of knowing, suggest the relationship between variables will be. This is the purpose of a literature review. You will notice that published academic research often includes a brief literature review of what other scholars have discovered on the topic. Consulting with an academic librarian can be helpful in performing a thorough literature review to include grey literature as well.

One basic way to conceptualize our research project broadly is to think about the cultural differences in how the world in general is viewed. From an Indigenous standpoint, typically all things are interconnected. All people and even animals, fish, birds, and plants are seen as interrelated. This way of seeing the world informs how we think and how we ask questions, and it impacts how we conduct research. From a stereotypical Western standpoint, on the other hand, things are viewed in a hierarchical and linear way with members of the dominant society at the top and everything else at different layers beneath them. As a result, research tends to name, label, describe, and then prescribe solutions from this vantage point, which tends to be self-serving (Redvers, 2019).

The debate about whether knowledge should include or exclude cultural components is central to understanding the difference between most Western research methods and most Indigenous research frameworks. Western research developed the use of the widely accepted empirical scientific method, in which knowledge is seen as objective and based on data that are independent of the feelings or values of the researcher: if it cannot be measured, it does not exist. However, many argue that true objectivity cannot be achieved and perhaps should not even be the goal of research. The fact that most research is conducted using the “objective” scientific method, while Indigenous ways of knowing are ignored, demonstrates a type of scientific colonialism, or abuse of power that Chilisa (2020, p. 7) defines as, “the imposition of the colonizer’s way of knowing and the control of all knowledge produced.”

Epistemology is the study of knowledge or ways of knowing, which is central to the practice of research. Epistemology delves into the nature of knowledge and truth. It challenges us to consider what it means to know something. How is knowledge distinguished from mere opinion or belief, and—importantly for social science—what are the ways by which we can derive or obtain knowledge? How might the latter differ across various cultures and contexts? Most Western researchers follow the Newtonian epistemology that “scientific knowledge has to provide an objective representation of the external world,” which it attempts to do by taking complex items and reducing them to their simplest components (Redvers, 2019, p. 43).

In fact, objectivity and empiricism are deemed to be the cornerstones of Western research: researchers must be detached from the research process, and all data must be observable and measurable to exist and become a part of scientific inquiry.

Choice of Method

As you think about what you are studying, you need to choose a particular method that is suited to answer your research question. For instance, determining someone’s opinion about something might best be captured by using a survey, whereas learning about actual behaviours may best be documented through observations in field research. Looking at what methods were used in other studies on the same or a similar topic may be helpful here.

It is now time for us to decide what method(s) we will use to complete our research projects. Our initial review of the literature in the planning stage, and then the deeper review in the conceptualization stage, would have given us a firm grasp of the types of methods used in other studies on the same or a similar topic. It may be possible as a researcher to combine an understanding of objectivity in research with the understanding of cultural subjectivity. As Abbott (2004, p. 3) puts it, “Science is a conversation between rigor and imagination.” The imaginative voice contributes to the excitement and discovery side of social science. We want to discover something new, such as the possible manipulation of one’s spiritual practices as a form of abuse, or something interesting about social life, such as elders being exploited financially but not reporting it. This will be something that, when combined with rigor, will allow us to draw a reasonable conclusion that can inform practice, improve the lives of elders, and allow us to share that knowledge with others by writing an article or book that could be published.

A methodology is the systematic contextual framework—a body of methods and rules used in a discipline—that guides the choices a researcher makes. A research method refers to the specific way of collecting and analysing data, such as through surveys, interviews, focus groups, or experiments. A statistical technique might then be used to describe the age and income of the research participants, or it might be a regression or other technique that helps us predict the characteristics of elders most likely to be manipulated or taken advantage of (these different statistical techniques will be explored further in your statistical research methods courses).

Typically, the techniques and methods taught and discussed in other texts are based on and advocate only the use of Western research. While it might seem that the approach does not really matter because research is scientific and objective, hopefully now the reader understands that there are power relations in the research process. Once an understanding of the importance of the overall research framework has been achieved, we can explore the basic research methods typically used and choose whatever seems most appropriate.

Since we have done our background research on the topic and consulted with knowledge holders including other experienced researchers, practitioners in the field, and knowledgeable members of the Indigenous community who could also benefit from our research, we need to develop a research strategy or process. Often the strategy will be either deductive or inductive and use either quantitative or qualitative methods (as explained in the Application Section). For instance, while researching financial exploitation, we are using parts of existing question sets that were developed from a theory about social control and have been used in other studies, to test whether we uncover financial exploitation happening to Indigenous elders. In doing so, we would be using a deductive approach with this particular project. A problem with this reductionist approach is that some frameworks—such as Indigenous frameworks—assume that we are all interconnected and so the whole is more than just its parts. Or, as Aristotle said, “the whole is more than the sum of its parts” (Redvers, 2019, p. 44). The Western view usually sees this knowledge as being situated outside of culture, but many Indigenous and other scholars insist that “knowledge” is within a cultural framework that may value or conversely marginalize who or what is counted as part of that “knowledge” (Walter & Andersen, 2016). However, as we conceptualize our research project moving forward, we will want to avoid using only a rigid Western view of the scientific method and be certain to learn from the Indigenous community helping us with the research while including relevant cultural components.

As we conceptualize our two research projects, we will want to continue to include the cultural components identified in step one, namely, Two-Eyed Seeing and the collaboration and cooperation between the researcher and the researched. Whatever method is chosen in the next step and for all future steps, we will want to be sure to involve the cultural community and maintain an open mind as they provide us with insights and feedback. We will strive to maintain a balance between scientific rigor and cultural inclusiveness while following ethical research practices and not bringing harm to our participants.

The other strategy may be to use an inductive approach, which fits well with qualitative methods. Inductive research first gathers data or information and then uses those data to develop a theory, discover themes, or draw conclusions. For instance, our research on spiritual abuse has no existing research to build from and we developed the idea in the planning stage by using a focus group and a research talking circle to gather thoughts and feelings about spiritual concerns from Indigenous elders. In a talking circle, the participants sit in a circle facing each other. The circle implies connectedness and the equality of each member. Typically, a sacred object such as a stone, feather or stick is held by the one speaking, and they have the chance to speak uninterrupted while the group listens until they pass the sacred item onto the next person (See Talking Circles).

The information learned in the talking circle allowed us as researchers to discover that the elders are concerned about losing their sacred cultural items through theft or the items being left behind if they are moved from their home. They also discussed not being transported to, or allowed to participate in, community spiritual ceremonies. These concepts are not typically addressed in most existing theories, policies, or programs, so it fits then that this project will use an inductive approach, which by definition is open to new and unanticipated concepts and findings to emerge, such as fear of the loss of cultural items and spiritual connection.

Before we move to the next step, let us also further clarify the difference between qualitative and quantitative research. As outlined later in the chapter in Table 3.1, quantitative research tends to use numbers or quantities as the most important element because this allows for abstraction. Many people such as members of the media and government agents, as well as the general population, are conditioned to believe findings if they have numbers attached. These methods allow us to draw from a local context with a sample, such as a sample of Indigenous elders from the one community, standardize it, and put it into a calculation to draw conclusions about larger numbers of people or broader social relations like “Indigenous elders from the Coushatta Tribe.” While a sample is sometimes generalizable to a population, there may be times when the sample is distinctly different from other samples and should not be generalized. For instance, a study of one reserve may produce results that are not generalizable to all Indigenous peoples. In determining generalizability, the key is determining how representative your sample is. A large random sample is more generalizable than a non-random sample or a small sample with a low response rate. The use of the survey and special closed-ended question sets makes our financial abuse research quantitative.

Qualitative methodologies tend to focus on specific localized objectives to examine them more in depth. Typically, subjective experiences of the participants are contextualized and influence the researcher’s understanding of the phenomenon in question. One qualitative technique is the use of focus groups or talking circles to understand the experiences of the participants and draw conclusions or notice patterns or trends within the participants’ comments. As mentioned, our spiritual abuse research has used this method, and we will be asking broad, open-ended questions so we are using the qualitative approach for this topic (see Table 3.1).

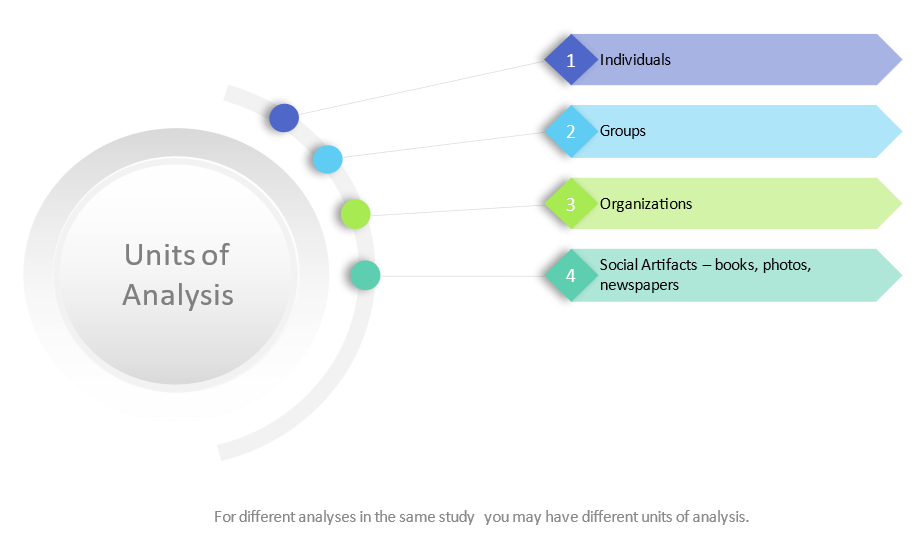

Another research design decision pertains to the element of time: can the question be answered using data that are collected at one point in time, known as cross-sectional research, or will they be collected at two or more points in time, known as longitudinal research. Both of our projects involve asking questions only once, so both projects are cross-sectional. Along with this decision, we need to decide on the unit of analysis, the who or what being studied. For both of our projects, the focus is on the individuals answering the questions, though our conclusions may be drawn about groups such as the Indigenous elderly of the Coushatta Tribe since that is the population the individuals were drawn from and there are things we learn about this group as a whole and that we can compare to other Indigenous groups. You will learn more about units of analysis in your future research methods courses, but Figure 3.3 below gives you an idea of the various units of analysis in the social sciences.

Before we move to the next step in the process, it is worth noting that the very idea that neither qualitative nor quantitative research is truly objective may make some researchers, and students of research, feel uncomfortable. When a central tenet of one’s epistemological position is challenged, it can be difficult to accept. This challenge is not only against the Western view of the objectivity of scientific research, but it also means that Indigenous research frameworks and other methods, such as feminist research, are also not completely objective, though such researchers are usually already aware of their social positioning.

Operationalization

Now that you have identified the concepts and chosen the most appropriate method to answer your research question, you must determine specifically how you will measure the concepts. This is called operationalization. For instance, in a survey, what specific wording for the questions and options for answers will accurately capture the concepts of interest? If you are doing field research, what specific observations will you be making?

Now that our concepts have been carefully considered and we know we will be asking questions with either quantitative scaled responses in the financial exploitation example or qualitative open-ended questions in the spirituality abuse example, we need to decide on the specific wording of the questions and the options we provide for possible answers, if any. In deciding on these specifics, we want to be careful not to marginalise the Indigenous elders we are studying.

Most research methodologies in the past, particularly quantitative ones, that have guided most data collection, analysis, and interpretation of data about Indigenous peoples, reflect in an almost invisible way the dominant Western cultural framework. Rather than representing a neutral view of reality, the research constitutes reality influenced by the very way the research questions are conceived in the first place and then how the data are collected and interpreted. Typically, the research efforts lean towards a documentation of not only difference but conclusions of deficit and dysfunction. And so, the people being studied are found to be the problem, and this finding is seldom critiqued. As Deloria (1988, p. 79, emphasis in original) explained it, “an anthropologist comes out to Indian reservations to make OBSERVATIONS. During the winter, those observations will become books by which future anthropologists will be trained, so they can come out to reservations years from now and verify the observations they have studied.”

We also want to design our questions so that our research is reliable. Reliability simply means being consistent. Once we explain how we did our research, someone else doing the same research in the same way should find the same results because our methods and explanations are clear and reliable. Or, if we repeat our measurements, they should yield the same results. This consistency can also be understood as replicability.

Sampling

Next, you need to consider who you are studying. You need to think about the overall population you want to draw conclusions about and then choose an appropriate sampling technique because that population is typically too large to study each and every member. Furthermore, if you are dealing with people instead of an official dataset, it may be difficult to obtain permission from everyone. The sample you end up with will be a subset of those data or people from the larger population.

For this step, we want to finalize our decision about what population we want to draw conclusions about and whether we will study every member of the population, or whether we will select a sample and decide how that sample will be selected, and how big that sample will be. These decisions may impact the validity and generalizability of our findings. For instance, if a sample is too small, it would not be valid to generalize our findings to a larger population. Or if we studied only select males, it would not be valid to assume the findings would be the same for females or other genders.

In our projects, we want to either understand the financial abuse or the spiritual abuse of Indigenous elders from a particular community. The sampling technique and the data collection methods used will differ. Let us assume there are roughly 307 elders in that community and there is an alphabetized list of who those elders are. For the financial exploitation study, which we want to study in a quantitative way, we could randomly select 100 of the names, which would be about one-third of the population, and as long as even 78 participated, we would have about 25% of the population included in our sample. What we find or do not find among those randomly selected individuals is likely also to be found or not present among the other elders as well, so our findings can be generalized. When determining your sample size, it is best to have a large sample when possible. A statistical technique known as power analysis can be used to determine the minimum sample size needed to run tests of statistical significance. For the spiritual abuse study, which we want to study in a qualitative way, we would be more interested in choosing participants who we know possess the key characteristics of interest. We would not rely on random sampling techniques; rather, we would strategically select a much smaller number of participants who we would interview using open-ended questions. While we will not be able to generalize in quite the same way as in our quantitative study, our data will be rich and detailed and will likely reveal information we did not anticipate.

The data collection process can take a considerable amount of time. For example, for our project on the financial exploitation of elders, we will cooperate with the tribal social service providers, who will contact the randomly selected elders, arrange a time to visit with them, help them complete the questionnaire and collect it from them. They will also be available to offer services such as a referral to counselling services or information on how to report a crime, if needed and wanted by the elders. For the spiritual abuse example, as mentioned, face-to-face, in-depth interviews will be conducted with a much smaller number of interviewees, but the data obtained will be rich and detailed. These interviews could take hours, scheduling interviews could prove to be challenging, and the analysis of pages and pages of interview notes could take weeks or longer.

Obtaining tribal permission to conduct these studies and then completing the ethical training of the service providers who administer the questionnaires in the financial exploitation study, or conduct in-depth interviews in the spirituality example, also takes time. Several months may be needed to make all the necessary arrangements and receive the required approvals from the tribe as well as our home institutional review board. Indigenous peoples are a protected class under research ethics protocols, and we will need to demonstrate that our research will benefit, or at least not harm, the participants in our research project. We will need to ensure that the individuals working with the elders understand that an elder can stop taking the survey or interview at any time and that it will not impact the ability of the elderly to use the social services normally provided. We will also need to train the service providers to not pry into details about abuse that are revealed in the survey or interview. Then, it will take time to set up the meetings with the elders and collect the responses/conduct the interviews. Collecting one’s own data can be helpful in addressing the initial research question(s), but it can be time consuming and costly to do it well. No matter the method ultimately used and the time this will entail, maintaining ethical standards throughout the research process is vitally important.

Before we set out to collect our data in the next step, we should carefully consider if the variables, hypothesis, and methods are appropriate for exploring the issues we are interested in, if they already exist in a data set we could use, or if we need to gather our own data. There are many accessible and quality sources of social science data. Each of these existing data sets will have some weaknesses, and we cannot change the questions or methods as the project has already been completed, so we have to work with what exists. However, performing secondary data analysis is a considerable time- and money-saving strategy. Examples of existing data sets include the UCR, which illustrates crimes from the perspective of the police; the GSS, which shares the perspective of crime victims and non-victims; and numerous collections of self-report data that reveal the offender’s perspective about crime and its commission. While these existing data sets do not contain the data we need for either of the research questions we are exploring in our illustrative examples in this chapter, it is important to acknowledge the existence of these secondary data sources; as such, these various methods measuring crime in Louisiana are explored in the textbox below.

Measuring Crime in Louisiana

In our projects, we are using Indigenous communities to research financial abuse of the elderly. Why are we doing this you might be asking yourself? That’s quite simple: Louisiana is home to 4 federally recognized Native tribes, and 11 state recognized tribes. They can be found here. It is always a wise idea to make sure we as researchers are cognizant of the fact that there are individuals/groups that are more often overlooked when discussing many issues regarding minority communities, and the Native American community in Louisiana is one of them.

The Uniform Crime Report (UCR) is an “incident-based” survey. This annual survey measures the incidence of crime in America. The federal government partners with the police community by collecting as much information from all police departments across the United States as possible about criminal incidents. The information collected includes information about the crime itself (such as the date and time), information about the victims and any known information about the accused. If more than one crime occurs during a single incident (such as someone being both hit and shot), only the most serious incident is recorded. Only crimes discovered by or reported to the police are included in this data set. If a group of people distrust the police, as is the case for many Indigenous peoples, then there will be a low rate of reporting, and though crimes have occurred they will not be recorded in the UCR. The ultimate goal of the UCR is to provide information for policy and legislative development and to compare between different jurisdictions within the United States and also internationally (see the UCR). Unfortunately, participation in providing crime data to the UCR is not universal. In Louisiana for example, only 78% of law enforcement agencies self-report their crime statistics to the UCR (see NIBRS).

As mentioned above, there are various reasons why a crime may not be reported to police. The Louisiana Violence Experiences Survey (LaVEX), for example, revealed that a significant portion of crimes are never reported to police and therefore never make it into the official record, i.e. the UCR. As such, the General Social Survey was created. This survey seeks to better understand how Americans perceive crime and the justice system and to capture information on their experiences of victimization (see the General Social Survey). The information is made public and available to politicians, policymakers, and scholars.

Data Processing

Next, you need to collect your data via whatever methods you have chosen. Data collection may happen quickly if, for instance, you had a short survey you administered to a small number of people. However, the collection process may instead take place over a long period of time, such as observing changes in inmates over a three-year study in a prison setting.

Depending on the method chosen, you now have a number of questionnaires with responses or perhaps notebooks full of recorded observations. These raw data will need to be processed into a useable form. While a fulsome discussion of the various levels of measurement is outside of the scope of an Introduction to Criminology textbook (typically this is covered in an introductory research methods course), it is important to understand at this stage that data (whether they are textual or numerical) are typically processed using either Excel or a statistical analysis program, such as SAS or SPSS, or if textual, a qualitative software program like Nvivo. The process involves extracting bits of data from the instrument used (such as the survey or the interview notes) and organizing them in such a way that allows for easy analysis.

Once all the data have been collected and returned to us, we now need to take the responses provided and turn them into useable data. The closed-ended questions will be converted into numbers, which are entered into a spreadsheet or other analysis program. We will need to develop a coding sheet where we agree, for instance, that a yes is entered as a 1 and a no is entered as a 0, while for other Likert scale-type questions, a strongly agree is entered as a 5 while a strongly disagree might be entered as a 1. By following consistent data entry rules, we will have fewer errors (Hagan, 2014). Our financial exploitation data will be completely quantitative, allowing numerical analysis to take place in the next step.

Even the open-ended questions in the spiritual abuse example, where participants answered questions in a lengthy face-to-face interview, will need to be processed in some way. Typically, the responses will be typed into a document or a discourse analysis program like NVivo so specific words and phrases can be grouped into categories for qualitative analysis and comparison. Our spiritual abuse data are predominantly qualitative, based on the in-depth interviews with open-ended questions about spirituality, spiritual practices, spiritual objects and any issues they have encountered in practising their spirituality.

Analysis

Once the data are processed, they must be analyzed. Analysis can be statistical in a quantitative project or thematic in a qualitative project. Either way, the qualitative goal of analysis is to make sense of the data and to synthesize and summarize the findings in a way that can be communicated to a larger audience. Graphs, tables, and charts are typically used to visually present data that have been analyzed. In this stage, we often refer to the literature again to connect what we have found in our own research to the existing body of knowledge.

In our financial exploitation example, as is the case with many research projects, most of the analysis will be statistical. While discussing all the different statistical methods is beyond the scope of this chapter, it is important to understand that a poor research design will lead to poor data. You can run an analysis on these data and the program will deliver a calculation, but any conclusions drawn based on that calculation will be faulty. If we have set up our research project correctly, we can have faith in the conclusions drawn from the analysis.

One reason why reliability and validity, which we discussed earlier, are so important is because research is often used not just to produce immediate findings, as these conclusions are used to generalise to a broader group or even predict an outcome or future event. If the current study is not done well, then any attempt to draw broader conclusions or anticipate what the future holds will be incorrect as well.

Since we took care in setting up our research projects, we can proceed with the analysis. In both our statistical analysis of survey responses and our qualitative analysis of interview responses, it is important to be aware of the translation-like process through which this non-academic knowledge that was shared with us is converted into conclusions by those of us in the academy. There may be important differences between “community or elder” and “academic” knowledge that needs to be identified so Indigenous viewpoints and knowledge can be acknowledged rather than silenced, even if they wrote something or answered questions in ways other than what we expected. At this stage, it is helpful to reflect on how our findings may overlap or diverge from the findings of past researchers and think about why that may be the case.

Application

The final stage of this research process is application, which involves using the conclusions you have reached to inform or educate others. At times, research can be used to influence policy making and may result in improvements such as fewer victimizations, fewer traffic accidents, and so on. As a final step, the researcher should also consider what errors may have been made that could be corrected in future research and, just as importantly, what future research would be helpful moving forward. This would be a valuable contribution to the literature and help other researchers identify gaps and choose their own research topics to explore. See Table 3.1 below for a summary of key features of the quantitative vs qualitative approaches and Figure 3.4 for a visual graphic of the inductive versus deductive approaches of research.

| Quantitative Research | Qualitative Research |

|---|---|

| focuses on testing or confirming theories and hypotheses | focuses on exploring ideas and understanding subjective experiences |

| focus on statistical analysis | focus on thematic, textual analysis |

| mainly expressed in numbers, graphs and tables | mainly expressed in words |

| requires many respondents | requires few respondents |

| closed-ended (multiple choice) questions | open-ended questions |

| methods include experiments, surveys | methods include interviews, field observation |

| key terms: testing, measurement, objectivity, replicability | key terms: understanding, context, complexity, subjectivity |

The final stage of our research projects is to use the conclusions we have reached to inform or educate others. Since we studied Indigenous elders in both of our examples, we would first present our findings to the tribal leaders. We would also share with them what we would like to present to others or what we would like to publish. This sharing and seeking of approval before broader dissemination of our results is often part of the agreement reached to conduct research with Indigenous peoples. It is also respectful of the concept of data sovereignty, wherein Indigenous peoples can control what data are collected about them and how results are disseminated. This agreement does not mean we change our results but that we are careful and thoughtful in how we interpret and communicate the results.

In the past, Indigenous peoples did not have control over studies completed on them, and there is currently often disagreement by researchers about the need for tribal approval before sharing their research with others (Macdonald et al., 2014). The current typical research expectation includes domination over “who can know, who can create knowledge, and whose knowledge can be bought” (Chilisa, 2020, p. 58). So, the term “academic imperialism” refers to how typical scholarly circles attempt to dismiss or diminish any alternative methodologies or perspectives such as data sovereignty (Chilisa, 2020). This dismissal often takes place through gatekeepers such as committees that approve courses and course content, editors that approve or deny article topics, granting agencies that approve or deny funding, and publishers that decide which manuscripts are worthy of publication. This very textbook is an example of current efforts to address these historical omissions of Indigenous knowledge in the field of criminology.

When appropriate, researchers may instead attempt to create and consciously use strategies to end oppressive conditions that silence and/or marginalize Indigenous or any other minority voices. Since the researcher has power over the subjects, they need to be thoughtful about any potential power dynamics such as teachers performing research on their students, employers conducting research on employees, or even being certain to still follow ethical guidelines when conducting research on people in positions of power. Researchers may also assist in the restoration or development of cultural practices and traditions that were suppressed but are still relevant to the advancement and empowerment of historically oppressed non-Western societies.

According to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (2022), approximately thirty-seven people in the United States die due to drunk driving accidents – that’s an estimated one person every thirty-nine minutes. 13,524 people died in 2022 as a result of traffic deaths by alcohol-impaired drivers. Every death was preventable.

Personal Statement, Dr. Franklyn Scott, Southern University of New Orleans

I was a Driving While Intoxicated (DWI) probation officer for approximately 12 years. I worked in the New Orleans Traffic Court Division C under the supervision of Retired Judge Paul A. Bonin (Figure 3.6) who was a Traffic Court Judge for a few decades. Judge Bonin encouraged me to study DWI defendants as my dissertation topic. I watched so many of my clients become repeat offenders. I remember one man young in particular who was trying to complete his probation requirements before his first child was set to arrive. He completed all requirements just in time for the birth of his baby boy, but he returned a month later as a 2nd offense DWI defendant. He told me he was out celebrating the birth of his baby and was again stopped and arrested for a DWI. His story was not an uncommon story because I would see several individuals return with a 2nd or 3rd offense.

In conducting research on habitual DWI defendants, I found that punishment was not the answer and due to most having an alcohol addiction, treatment was essential. My former mentor Judge Bonin would always say, “It is not against the law to drink but drinking and driving is.” Most would not understand that life for them would have been so much easier if they would have at the time taken a cab or opted for a designated driver. There was not ride sharing during my time as a probation officer. There were cab accounts that could have been created and there was always the option of calling a relative for a ride home. All solutions above would have solved the problem. Punishment has not been proven to be effective, and many researchers suggest punishment with treatment could be more beneficial. However, if the need to drink was viewed in a positive manner, the consequences would not matter.

You can read my full dissertation here.

9 Steps of the Research Process: A Brief Illustration

In New Orleans, Louisiana multiple Driving While Intoxicated (DWI) and Driving Under the Influence (DUI) offenses are committed in spite of punishments being imposed (Scott, 2015). An understanding of how punishment impacts the defendants from their perspective is vital to aiding research in creating alternative sanctions that could decrease recidivism. Below is a brief discussion on how the research was gathered for my dissertation utilizing the 9 steps of the research process.

Planning

In this study I sought to describe the defendants’ behaviors that perpetrated repeated offenses in despite the harshness of punishments imposed.

Conceptualize

Research Question

1. How do DWI and DUI defendants describe their punishment?

2. How do the DWI and DUI defendants describe their lives after completing

their punishment?

3. How has the impact of punishment changed these defendants’ lives?

4. What are the perceptions of the defendants towards DWI and DUI?

5. How do the defendants describe their DWI and DUI behaviors?

Choice of Method

In this study, the case study method was employed.

Operationalization

The purpose of this research was to gain a clearer understanding of how punishment impacts these crimes in order to develop punishments that will effectively reduce recidivism.

Sampling

This study employed one-on-one interviews with participants that were currently on probation for a DWI or DUI offenses. The study method included the sample and the targeted population. The sampling strategy for this study was criterion sampling.

Data Collection

The research questions provided the basis for data collection. The punishment and driving practices during and after the offenses of DWI and DUI were the focus of all of the questions asked during the research process.

Data Processing

Excel was used for data coding. All discrepancy cases were reported if they did not fit the identified themes by other participants. Data was maintained in collection manner. Upon completion of the interviewing process, analysis of data occurred immediately. For the purpose of sorting, the data was viewed, reviewed, and checked multiple times.

Analysis

All responses to each question by participants during the interview process was thoroughly read. I noted the emerging responses, patterns, and themes amongst the participants.

Applications

Based on research, there is no solution to this problem. The participants in this study thought their punishment was meaningful and vowed to not commit similar crimes in the future.

In Louisiana, drivers are required to give consent to submit to a blood alcohol test (BAC) and it’s against the law to refuse. Consequences for driving under the influence (DUI) include:

- BAC below 0.08: License may not be suspended if the driver consents to a breathalyzer test.

- BAC 0.08 or higher: 90-day license suspension and a DWI arrest.

- BAC higher than 0.15: Longer license suspensions and harsher court penalties.

- Refusing to provide a sample: 365-day license suspension and a DWI arrest.

Louisiana’s BAC limit was lowered from 0.10% to 0.08% about 15 years ago. Studies have shown that lowering the BAC limit reduces alcohol-related crashes, fatalities, or injuries.

Critical Thinking Discussion

Write a brief narrative about your first college course or something your classmates agree on. Then, compare narratives with your friends and see if you can identify common themes.

an explanation for observed facts and laws that relate to a particular phenomenon. It is made up of a set of concepts and an explanation of how these concepts are related to one another.

a proposed explanation used as a starting point in the deductive model for further investigation, or emerging at the end of the research process in the inductive model. A hypothesis is typically written as an “if, then” statement and outlines how we expect the variables to be related to one another and the direction of that relationship.

a person, place, thing, or phenomenon you are trying to measure in some way.

blending of Indigenous worldviews and Western science.

only learning from big name authors in mainstream journals.

literature or evidence that is relevant to the research question but not published in typical commercial or academic peer-reviewed publications.

a summary and analysis of existing research on a specific topic.

the imposition of the colonizer’s way of knowing and the control of all knowledge produced.

the study of knowledge or ways of knowing.

lack of favoritism toward one side or another.

the idea that all learning comes from only experience and observations.

a method of collecting data by asking respondents questions in a questionnaire.

a qualitative method that involves observing and possibly interacting with research subjects in their natural environment.

being based on or influenced by personal feelings, tastes, or opinions.

systematic contextual framework—a body of methods and rules used in a discipline—that guides the choices a researcher makes.

the specific way of collecting and analysing data.

a method of gathering information using relevant questions from a sample of people with the aim of understanding populations as a whole.

a formal consultation usually to evaluate qualifications.

a research technique used to collect data through group interaction.

a scientific procedure undertaken to make a discovery, test a hypothesis, or demonstrate a known fact.

a structured discussion where participants share their thoughts and feelings in a safe, non-judgmental space.

a subset of people or things from the larger population we want to know more about. In quantitative research, our samples are larger than in qualitative research.

data that are collected at one point in time.

a type of study that involves repeatedly observing the same variables over a long period of time.

essentially the "who" or "what" being examined in a study.

turning abstract concepts or phenomena that may not be directly observable into measurable observations. For example, this would involve selecting the exact wording of survey questions.

the consistency and repeatability of a measurement.

all members of a particular area or group, or all things, that you want to learn more about from which a sample is drawn.

the process of selecting which people or things to research (i.e. selecting our sample) from the larger population, with the typical goal of generalizing our findings from the sample to the population. In quantitative research, our sampling techniques are random, while in qualitative research, we use non-random sampling techniques to select those people or things with specific characteristics of interest.

data sets often produced by official governmental agencies for administrative purposes, such as Census data or crime figures.

the quality of being well-grounded, sound, or correct.

a measure of how well the results of a study can be applied to a larger group of people or situations.

data that was collected by someone other than the current user.

data collected directly from the source and that exist at this point without any processing, transformation, or analysis. Interview notes or survey responses are examples of raw data.

the process of compiling and reviewing information, and then summarizing and synthesizing the data, often with the aide of statistical techniques, to reach a conclusion or explanation about the phenomenon under study.

research that involves the collection and analysis of numerical data. It can involve testing causal relationships and making predictions. Methods include closed-ended surveys and experiments.

research that involves the collection and analysis of in-depth textual or verbal, non-numerical data. Methods include interviews, focus groups, and field observation.

the idea that data should be governed by the laws of the country or region where it's stored, collected, or generated.

a person or thing that controls access to something.