Chapter 11 ~ Environmental Justice

Key Terms

Applied ethics, environmental equity, environmental ethics, environmental justice, frontier ethic, indigenous people, land ethic, Legionnaires disease, sustainable ethic, tragedy of the commons

Learning Objectives

Upon completion of this chapter, students will be able to:

- Explain the significance of environmental justice in the context of environmental science.

- Define environmental ethics and how communities are affected in decision-making.

- Differentiate between the environmental worldviews.

- Explain significant incidents of environmental injustice (i.e., environmental racism).

- Explain the interconnectedness of social, economic, and environmental factors relating to environmental justice.

Chapter Overview

- Introduction

- Environmental Ethics

- Environmental Equity and Justice

- Environmental Inequities in Vulnerable Communities

- Addressing Environmental Injustices

- Chapter Summary

Introduction

As the closing chapter of this textbook, it is imperative to discuss the social and economic impacts related to the covered environmental topics in chapters 1–10. This section defines environmental justice and the need for implementing it in all spaces. This section also highlights case studies demonstrating environmental inequities.

Environmental Ethics

Foundations of Environmental Ethics

Most of us think about ethical issues in our everyday lives. We might wonder, for instance, whether we must reduce our use of plastics because of their environmental impact. We might question whether we treated someone fairly at work or whether we acted in a morally problematic way. We engage in applied ethics when we reflect on whether a given action is right or wrong. We attempt to determine the rightness of some specified action through moral deliberation and applying ethical principles and norms. Questions in applied ethics focus on whether some action is right, and philosophers implement diverse perspectives when analyzing the morality of a specific action.

Developments and advances in technology and medicine can potentially create otherwise unforeseen or unexpected ethical dilemmas. In most cases, it is very difficult, if not impossible, to predict potential ethical issues about an innovation until it is already in use and the world. Imagine, for instance, trying to predict what moral dilemmas and disruptions the internet would cause before it was created and widely used. Indeed, even after its creation and widespread adoption in the 1990s, there were still many innovations and challenges to come that would have been hard to predict. Ethical dilemmas created by innovations emerge with use. These dilemmas lead to confrontation and debate only after they become apparent. This is why it can sometimes seem like ethical debates are always playing catch-up, that we are motivated to debate the ethical implications of something only after issues become apparent.

Metaethics, normative ethics, and applied ethics are the three main areas of ethics that are each distinguished by a different level of inquiry and analysis. Applied ethics focuses on the application of moral norms and principles to controversial issues to determine the rightness of specific actions. People have performed applied ethics throughout human history. As a field of study, applied ethics is relatively new, emerging in the early 1970s. Issues like abortion, environmental racism, the use of humans in biomedical research, and online privacy are just a few of the controversial moral issues explored in applied ethics. New subfields of applied ethics are emerging, such as Artificial intelligence (AI) ethics.

Before environmental ethics emerged as an academic discipline in the 1970s, some people were already questioning and rethinking our relationship with the natural world. Aldo Leopold’s A Sand County Almanac, published in 1949, called upon humanity to expand our idea of community to include the entire natural world, grounding this approach in the belief that all of nature is connected and interdependent in important ways. Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring (1962) drew attention to the dangers of what were then commonly used commercial pesticides. Carson’s essays drew attention to the far-reaching impacts of human activity and its potential to cause significant harm to the environment and humanity. These early works inspired the environmentalist movement and sparked debates about how to deal with emerging environmental challenges.

Humans directly and indirectly change and shape the natural world. Our reliance on fossil fuels to meet our energy needs, for example, releases a key greenhouse gas, carbon dioxide (CO2), into the air. Greenhouse gases trap heat in Earth’s atmosphere, resulting in changes in the planet’s climate. The two countries that produce the most CO2 are the United States and China. The United States is the biggest gasoline consumer in the world, using approximately 370 million gallons of gasoline per day in 2022. China is the biggest coal consumer, burning approximately three billion tons of coal in 2022—more than half of the worldwide total coal consumption. Our demand for the energy provided by fossil fuels to power our industries, heat our homes, and make travel possible between distant locations is the main factor contributing to increased levels of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.

Human activities have and continue to significantly impact the natural world. Anthropogenic climate change refers to changes in Earth’s climate caused or influenced by human activity. Severe weather and natural disasters are increasing in frequency and intensity because of the changing climate. One example is the recent record-setting wildfires in the United States and Australia. In a span of just five years (2017–2021), the United States experienced four of the most severe and deadliest wildfires in its history, all of which occurred in California: the 2017 Tubbs Fire, the 2018 Camp Fire, the 2020 Bay Area Fire, and the 2021 Dixie Fire. In 2020, Australia experienced its most catastrophic bushfire season when roughly 19 million hectares burned, destroying over three thousand homes and killing approximately 1.25 billion animals. In 2023, Louisiana experienced unprecedented heat and drought that spurred a statewide burn because of the hundreds of wildfires in August.

Environmental ethics is an area of applied ethics that attempts to identify the right conduct in our relationship with the nonhuman world. For decades, scientists have expressed concern about the short- and long-term effects of human activities on the climate and Earth’s ecosystems. Many philosophers argue that to change our behaviors in ways that result in the healing of the natural world, we need to change our thinking about the agency and value of the nonhuman elements (including plants, animals, and even entities such as rivers and mountains) that share the globe with us. Environmental ethics exist in three groups that address the agency and value (or non-value) of nonhuman elements: frontier, sustainable, and land ethic.

Frontier Ethic

Ethical attitudes and behaviors determine human interaction with the land and its natural resources. Early European settlers in North America rapidly consumed the land’s natural resources. After they depleted one area, they moved westward to new frontiers. Their attitude toward the land was that of a frontier ethic. A frontier ethic assumes that the earth has an unlimited supply of resources. If resources run out in one area, more can be found elsewhere, or human ingenuity will find substitutes. This attitude sees humans as masters who manage the planet. The frontier ethic is completely anthropocentric (human-centered).

Most industrialized societies experience population and economic growth based upon this frontier ethic, assuming that infinite resources exist to support continued growth indefinitely. Economic growth is considered a measure of how well a society is doing. The late economist Julian Simon pointed out that life on earth has never been better and that population growth means more creative minds to solve future problems and give us an even better standard of living. However, now that the human population has passed eight billion and few frontiers are left, many are beginning to question the frontier ethic. Such people are moving toward an environmental ethic, which includes humans as part of the natural community rather than managers of it. Such an ethic limits human activities that may adversely affect the natural community (e.g., uncontrolled resource use).

Some of those still subscribing to the frontier ethic suggest that outer space may be the new frontier. If we run out of resources (or space) on Earth, they argue, we can simply populate other planets. This seems an unlikely solution, as even the most aggressive colonization plan would be incapable of transferring people to extraterrestrial colonies at a significant rate. Natural population growth on Earth would outpace the colonization effort. A more likely scenario would be that space could provide the resources (e.g., from asteroid mining) that might help to sustain human existence on Earth.

Sustainable Ethic

A sustainable ethic is an environmental ethic by which people treat the earth as if its resources are limited. This ethic assumes that the earth’s resources are not unlimited and that humans must use and conserve resources to allow their continued use in the future. A sustainable ethic also assumes that humans are a part of the natural environment and that we suffer when the health of a natural ecosystem is impaired. A sustainable ethic includes the following tenets:

- The earth has a limited supply of resources.

- Humans must conserve resources.

- Humans share the earth’s resources with other living things.

- Growth is not sustainable.

- Humans are a part of nature.

- Humans are affected by natural laws.

- Humans succeed best when they maintain the integrity of natural processes and cooperate with nature.

For example, if a fuel shortage occurs, how can the problem be solved consistently with a sustainable ethic? The solutions might include finding new ways to conserve oil or developing renewable energy alternatives. A sustainable ethic attitude, in the face of such a problem, would be that if drilling for oil damages the ecosystem, then that damage will also affect the human population. A sustainable ethic can be either anthropocentric or biocentric (life-centered). An advocate for conserving oil resources may consider all oil resources as the property of humans. Using oil resources wisely so that future generations have access to them is an attitude consistent with an anthropocentric ethic. Using resources wisely to prevent ecological damage is in accord with a biocentric ethic.

Land Ethic

Aldo Leopold, an American wildlife natural historian and philosopher, advocated a biocentric ethic in his book, A Sand County Almanac. He suggested that humans had always considered land as property, just as ancient Greeks considered slaves as property. He believed that mistreatment of land (or of slaves) makes little economic or moral sense, much as today, the concept of slavery is considered immoral. All humans are merely one component of an ethical framework. Leopold suggested that land be included in an ethical framework, calling this the land ethic.

“The land ethic simply enlarges the boundary of the community to include soils, waters, plants and animals; or collectively, the land. In short, a land ethic changes the role of Homo sapiens from conqueror of the land-community to plain member and citizen of it. It implies respect for his fellow members, and also respect for the community as such” (Aldo Leopold, 1949).

Leopold divided conservationists into two groups: one group that regards the soil as a commodity and the other that regards the land as a biota, with a broad interpretation of its function. If we apply this idea to the field of forestry, the first group of conservationists would grow trees like cabbages while the second group would strive to maintain a natural ecosystem. Leopold maintained that the conservation movement must be based upon more than just economic necessity. Species with no discernible economic value to humans may be an integral part of a functioning ecosystem. The land ethic respects all parts of the natural world regardless of their utility, and decisions based upon that ethic result in more stable biological communities.

“Anything is right when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability and beauty of the biotic community. It is wrong when it tends to do otherwise” (Aldo Leopold, 1949).

Worldviews in Environmental Science

Chapter 1 introduced worldviews and the interactivity between humans and the natural world. Table 11.1 highlights the characteristics of five existing worldviews in environmental science.

Table 11.1. Existing worldviews in environmental science

|

Existing Worldviews |

Characteristics |

|

Anthropocentric |

Humans are at the center of moral consideration. Judges the importance and worthiness of everything in terms of the human welfare implications, including other species and ecosystems. |

|

Biocentric |

Focuses on living entities and considers all species (and individuals) as having intrinsic value. This worldview rejects discrimination against other species. |

|

Ecocentric |

Considers the direct and indirect connections among species within ecosystems to be invaluable. Incorporates the biocentric worldview and stresses the importance of interdependent ecological functions, such as productivity and nutrient cycling. |

|

Frontier |

Humans have a right to exploit nature by consuming natural resources in boundless quantities, because new stocks can always be found, or substitutes discovered. |

|

Sustainability |

Humans must have access to vital resources, but the exploitation of those necessities should be governed by appropriate ecological, intrinsic, and aesthetic values. |

The attitudes of people and their societies toward other species, natural ecosystems, and resources have enormous implications for environmental quality. Extraordinary damages have been legitimized by attitudes based on a belief in the inalienable right of humans to harvest whatever they desire from nature without consideration of pollution, threats to species, or the availability of resources for future generations. One of the keys to resolving the environmental crisis is to achieve widespread adoption of ecocentric and ecological sustainability worldviews.

Case Study: Hetch Hetchy Valley

In 1913, the Hetch Hetchy Valley—located in Yosemite National Park in California—was the site of a conflict between two factions, one with an anthropocentric ethic and the other with a biocentric ethic. As the last American frontiers were settled, the rate of forest destruction started to concern the public.

The conservation movement gained momentum but quickly broke into two factions. One faction, led by Gifford Pinchot, Chief Forester under Teddy Roosevelt, advocated utilitarian conservation (i.e., conservation of resources for the public good). The other faction, led by John Muir, advocated the preservation of forests and other wilderness for their inherent value. Both groups rejected the first tenet of frontier ethics, the assumption that resources are limitless. However, the conservationists agreed with the rest of the tenets of frontier ethics, while the preservationists agreed with the tenets of the sustainable ethic.

The Hetch Hetchy Valley was part of a protected National Park. After the devastating fires of the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, residents of San Francisco wanted to dam the valley to provide their city with a stable supply of water. Gifford Pinchot favored the dam.

“As to my attitude regarding the proposed use of Hetch Hetchy by the city of San Francisco…I am fully persuaded that…the injury…by substituting a lake for the present swampy floor of the valley…is altogether unimportant compared with the benefits to be derived from its use as a reservoir.”

“The fundamental principle of the whole conservation policy is that of use, to take every part of the land and its resources and put it to that use in which it will serve the most people” (Gifford Pinchot, 1913).

John Muir, the founder of the Sierra Club and a great lover of wilderness, led the fight against the dam. He saw wilderness as having an intrinsic value, separate from its utilitarian value to people. He advocated the preservation of wild places for their inherent beauty and for the sake of the creatures that live there. The issue aroused the American public, who were becoming increasingly alarmed at the growth of cities and the destruction of the landscape for commercial enterprises. Key senators received thousands of letters of protest.

“These temple destroyers, devotees of ravaging commercialism, seem to have a perfect contempt for Nature, and instead of lifting their eyes to the God of the Mountains, lift them to the Almighty Dollar” (John Muir, 1912).

Despite public protest, Congress voted to dam the valley. The preservationists lost the fight for the Hetch Hetchy Valley. Their questioning of traditional American values had some lasting effects. In 1916, Congress passed the “National Park System Organic Act,” which declared that parks were to be maintained in a manner that left them unimpaired for future generations. As we use our public lands, we continue debating whether we should be guided by preservationism or conservationism.

Case Study: Tragedy of the Commons

The Tragedy of the Commons was introduced in chapter one. It applies to what is arguably the most consequential environmental problem: global climate change. The atmosphere is a commons into which countries are dumping carbon dioxide from the burning of fossil fuels. Although we know that the generation of greenhouse gases will have damaging effects on the globe, we continue to burn fossil fuels. As a country, the immediate benefit from the continued use of fossil fuels is seen as a positive component (because of economic growth). All countries, however, will share the negative long-term effects.

The SARS-CoV-2 disease leading to the COVID-19 pandemic revealed notions of the Tragedy of the Commons. Maaravi et al. (2021) explored the impact of COVID-19 (number of cases and deaths) based on culture in 69 countries. The study assessed culture using data from the Hofstede National Culture Survey and assigned individualism scores to the countries. Scores were either categorized as individualistic (focuses on personal interest) or collectivistic (focuses on society and the common good). The study revealed countries with a score leaning toward individualism (versus collectivism) had higher COVID-19 cases and mortality rates. Therefore, the study highlighted the tragedy of individualistic countries during the pandemic and the social implications of considering the greater good in moving toward a more collectivistic society.

The Tragedy of the Commons is a frequent economic and social framework for discussions about a range of common resources, even extending into digital resources such as open media repositories and online libraries. Prominent economist Elinor Ostrom, the first woman to receive the Nobel Prize in Economics, proposed an alternate version, sometimes referred to as the “non-tragedy of the commons.” After extensive fieldwork in areas as diverse as Indonesia, Kenya, Maine, the United States, and Nepal, she challenged the notion that people would only avoid depletion of common resources if required by regulatory laws and property rights. She noted that farmers working on shared land could communicate and cooperate to maximize and preserve the fields over time. She argued that when those who benefit most from a resource are near it (like a farm field that directly serves a town), the resource is managed better without external influence.

Environmental Equity and Justice

Environmental Equity

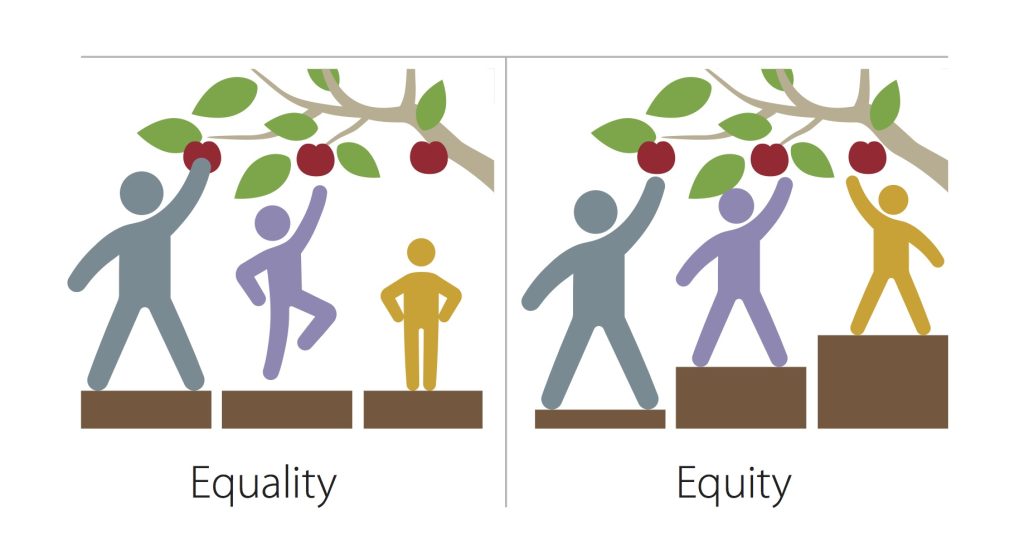

Equity addresses the need to provide people with the necessary tools to obtain their wants or needs. Figure 11.2 explains the difference between equality and equity in meeting similar outcomes for all people. Therefore, environmental equity acknowledges the need for the fair treatment, safety, and protection of individuals from environmental hazards and disasters irrespective of their income and access to resources.

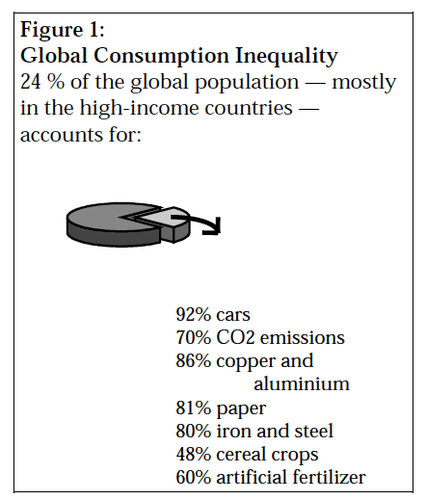

While much progress is being made to improve resource efficiency, far less progress has been made to improve resource distribution. Currently, just one-fifth of the global population is consuming three-quarters of the earth’s resources (Figure 11.3). If the remaining four-fifths were to exercise their right to grow to the level of the rich minority, it would result in ecological devastation. So far, global income inequalities and lack of purchasing power have prevented poorer countries from reaching the standard of living (and also resource consumption or waste emission) of the developed countries.

However, countries such as China, Brazil, India, and Malaysia are catching up fast. In such a situation, global consumption of resources and energy needs to be drastically reduced to a point where it can be repeated by future generations. But who will do the reduction? Poorer nations want to produce and consume more. Yet so do richer countries: their economies demand ever greater consumption-based expansion. Such stalemates have prevented any meaningful progress toward equitable and sustainable resource distribution at the international level. These issues of fairness and distributional justice remain unresolved.

Environmental Justice

Environmental justice is the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income concerning the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies. It will be achieved when everyone enjoys the same degree of protection from environmental and health hazards and equal access to the decision-making process to have a healthy environment to live, learn, and work.

Dr. Robert Bullard, an environmental sociologist, is referred to as the “Father of Environmental Justice” for his work addressing injustices in marginalized communities. In 1979, his wife, Linda McKeever Bullard, was the plaintiff attorney for the Bean v. Southwestern Waste Management Corporation lawsuit in Houston, Texas. Despite losing this unprecedented case, it was the impetus that fueled legal endeavors against corporations negatively affecting marginalized communities.

During the 1980s, minority groups protested that hazardous waste sites were preferentially located in minority neighborhoods. In 1987, Benjamin Chavis of the United Church of Christ Commission for Racism and Justice coined the term environmental racism to describe such a practice. The charges generally failed to consider whether the facility or the demography of the area came first. Most hazardous waste sites are located on property that was used as disposal sites long before modern facilities and disposal methods were available. Areas around such sites are typically depressed economically, often from past disposal activities. Persons with low incomes are often constrained to live in such undesirable, but affordable, areas. The problem more likely resulted from one of insensitivity rather than racism. Indeed, the ethnic makeup of potential disposal facilities was most likely not considered during the site selection.

Decisions in citing hazardous waste facilities are generally made based on economics, geological suitability, and the political climate. For example, a site must have a soil type and geological profile that prevents hazardous materials from moving into local aquifers. The cost of land is also an important consideration. The high cost of buying land would make it economically unfeasible to build a hazardous waste site in Beverly Hills. Some communities have seen a hazardous waste facility as a way of improving their local economy and quality of life. Emelle County, Alabama, had illiteracy and infant mortality rates that were among the highest in the nation. A landfill constructed there provided jobs and revenue that ultimately helped to reduce both figures.

An ideal world would have no hazardous waste facilities. But, we live in a world plagued by rampant pollution and dumping of hazardous waste. Our industrialized society has necessarily produced waste during the manufacturing of products for our basic needs. Until technology can find a way to manage (or eliminate) hazardous waste, disposal facilities will be necessary to protect both humans and the environment. By the same token, this problem must be addressed. Industry and society must become more socially sensitive when selecting future hazardous waste sites. All humans who help produce hazardous wastes must share the burden of dealing with those wastes, not just the poor and minorities.

In 1992, the United States Office of Environmental Equity was established. It became the Office of Environmental Justice under the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). This office oversees programs, partnerships, and tools that address disparities affecting indigenous, low-income, minority, and tribal citizens. The next section will explore instances that involve inequities for these vulnerable communities.

Environmental Inequities in Vulnerable Communities

Vulnerable communities experience environmental injustice and inequities for several reasons. Vulnerable communities are typically minority communities or low-income households. These individuals are often denied input in policy-making decisions or legislation. Therefore, these groups are impacted by environmental practices that may lack oversight and protection. Considerations may not be given to the long-term impacts of decisions that affect these communities. Lastly, these communities are disproportionately subjected to environmental hazard(s).

Loyola University, located in New Orleans, Louisiana, established the Loyola Jesuit Social Research Institute (JSRI). One task of this institute is measuring and comparing social justice across the United States. JSRI created the JustSouth Index in 2016 to examine three dimensions of social justice: poverty, disparity, and immigrant exclusion. For two consecutive years (2016–2018), Louisiana ranked 51 out of 51. In 2019, Louisiana moved above Mississippi to rank 50 out of 51. These numbers are concerning and highlight the need for improvements in Louisiana and other states experiencing slow to no advancement toward social justice. The JustSouth Index reports for 2016–2019 are available for review.

Indigenous People

Since the end of the fifteenth century, established nations have claimed and colonized most of the world’s frontiers. Invariably, these conquered frontiers were home to people indigenous to those regions. Some were wiped out or assimilated by the invaders. Others survived while trying to maintain their unique cultures and way of life. The United Nations officially classifies indigenous people as “having a historical continuity with pre-invasion and pre-colonial societies” and “consider themselves distinct from other sectors of the societies now prevailing in those territories or parts of them.” Furthermore, indigenous people are “determined to preserve, develop and transmit to future generations, their ancestral territories, and their ethnic identity, as the basis of their continued existence as peoples, in accordance with their own cultural patterns, social institutions and legal systems” (United Nations, 2004). A few of the many groups of indigenous people around the world are the many tribes of Native Americans (i.e., Navajo, Cherokee, Mexican American Indian, Chippewa, Sioux) in the contiguous 48 states, the Inuit of the arctic region from Siberia to Canada, the rainforest tribes in Brazil, the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people of Australia, the Sami of northern Europe, the Ainu of northern Japan, and the Maori of New Zealand.

Many problems face indigenous people, such as the lack of human rights, exploitation of their traditional lands and themselves, and degradation of their culture. In response to the problems faced by these people, the United Nations proclaimed an “International Decade of the World’s Indigenous People” beginning in 1994. This proclamation’s main objective, according to the United Nations, is “the strengthening of international cooperation for the solution of problems faced by indigenous people in such areas as human rights, the environment, development, health, culture and education.” Its goal is to protect the rights of indigenous people. Such protection would enable them to retain their cultural identities, such as their language and social customs while participating in the political, economic, and social activities of the region in which they reside.

Despite the lofty U.N. goals, the rights and feelings of indigenous people are often ignored or minimized, even by supposedly culturally sensitive developed countries. In the United States, many of those in the federal government are pushing to exploit oil resources in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge on the northern coast of Alaska. The “Gwich’in,” an indigenous people who rely culturally and spiritually on the herds of caribou that live in the region, claims that drilling in the region would devastate their way of life. A few months’ oil supply would destroy thousands of years of culture. Drilling efforts have been stymied in the past but mostly out of concern for environmental factors and not necessarily the needs of the indigenous people. Curiously, another group of indigenous people, the “Inupiat Eskimo,” favor oil drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. Because they own considerable amounts of land adjacent to the refuge, they would potentially reap economic benefits from the development of the region.

The heart of most environmental conflicts faced by governments usually involves what constitutes proper and sustainable levels of development. For many indigenous peoples, sustainable development constitutes an integrated wholeness, where no single action is separate from others. They believe that sustainable development requires the maintenance and continuity of life from generation to generation and that humans are not isolated entities but are part of larger communities, which include the seas, rivers, mountains, trees, fish, animals, and ancestral spirits. These, along with the sun, moon, and cosmos, constitute a whole. From the point of view of indigenous people, sustainable development is a process that must integrate spiritual, cultural, economic, social, political, territorial, and philosophical ideals.

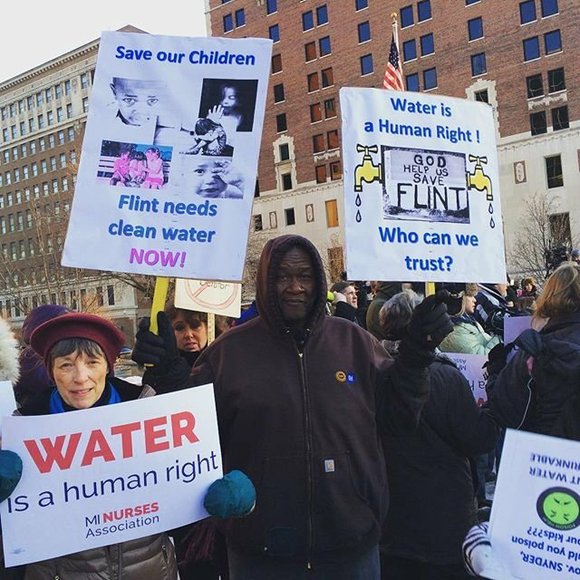

Flint, Michigan

Detroit is the most populous city in Michigan—a population of 632,464 residents as of 2021. According to the 2021 census, approximately 80% of the residents identify as racial minorities. The median household income is approximately $35,000. Approximately 30% of residents live in poverty. Detroit has been known as the birth of the automobile industry (early 1900s) and Motown Records (founded in 1959). These significant industries brought economic prosperity to Detroit in manufacturing jobs and entertainment revenue from the 1940s through the 1960s. However, Detroit declined greatly in the 1970s due to decreased economic opportunities, people migrating from the city to nearby suburban communities, housing issues, racial discrimination, and increased violence. The 2008 financial crisis led to the government bailout of General Motors and Chrysler automotive facilities by the federal government, which allowed them to succeed through the turmoil. But Detroit filed for bankruptcy in 2013. The city is recovering, but repercussions have persisted years later. Flint, Michigan, is approximately 70 miles north of Detroit, Michigan. According to the 2013 United States Census Bureau, the Flint population was 99,487. As of 2022, the population is 79,854, and over 50% identify as a racial minority.

In April 2014, the City of Flint, Michigan, began looking for cheaper water due to its growing population, which prompted a switch from the Detroit water supply to the Flint River. Water supply for public consumption undergo quality control testing measures, such as pH, bacterial growth, temperature, and trace elements, such as fluorine. The Detroit River has been the water source for 46 years and has undergone water quality testing. The Flint River’s quality was not tested until 2015 when researchers discovered lead in the drinking water. Residents of Flint, Michigan, were exposed to the contaminated water for one and a half years before the city switched the water back to the Detroit River in October 2015. The city declared a public health emergency due to lead exposure and other health concerns.

The health effects from the contaminated water were drastically present: lead exposure and Legionnaires’ disease. The number of children under 5 with elevated lead levels in their blood increased from 2.1% in 2013 to 4.0% in 2015. Lead exposure is known to cause lifelong issues for survivors. The children are at risk for developing kidney damage, nervous system damage, and anemia. Adults who experience prolonged exposure are at an increased risk for high blood pressure, heart disease, and kidney. Lead exposure even affects fertility and causes poor birth outcomes. Legionnaires’ disease is caused by the bacterium Legionella pneumophila. This bacterium can be found in freshwater or warm-water pipes in air-conditioning units. The Flint River contained this bacterium. There were 91 confirmed cases of Legionnaires’ disease and 12 deaths.

Unfortunately, residents complained about the unsafe and unsanitary water conditions for a while but were dismissed by city officials. Multiple agencies were criticized for delayed or ineffective responses. The county-level agency was the Genesee County Health Department. The state-level agencies were the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality and the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services. There were also inefficiencies at the national level from the EPA. The Flint Water Advisory Task was established to identify the issues and provide recommendations for a resolution. Once the agency’s roles were identified, action was taken to address these agencies for immediate resolutions through lawsuits and criminal charges. Resulting actions included replacing pipe infrastructure contaminated with lead and water testing and treatment. However, there are still unresolved issues in 2023 and lingering effects of the contaminated water exposure.

Legionnaires’ Disease Water Crisis

This PBS Frontline episode explores an outbreak of Legionnaires’ disease in Flint, Michigan:

Cancer Alley

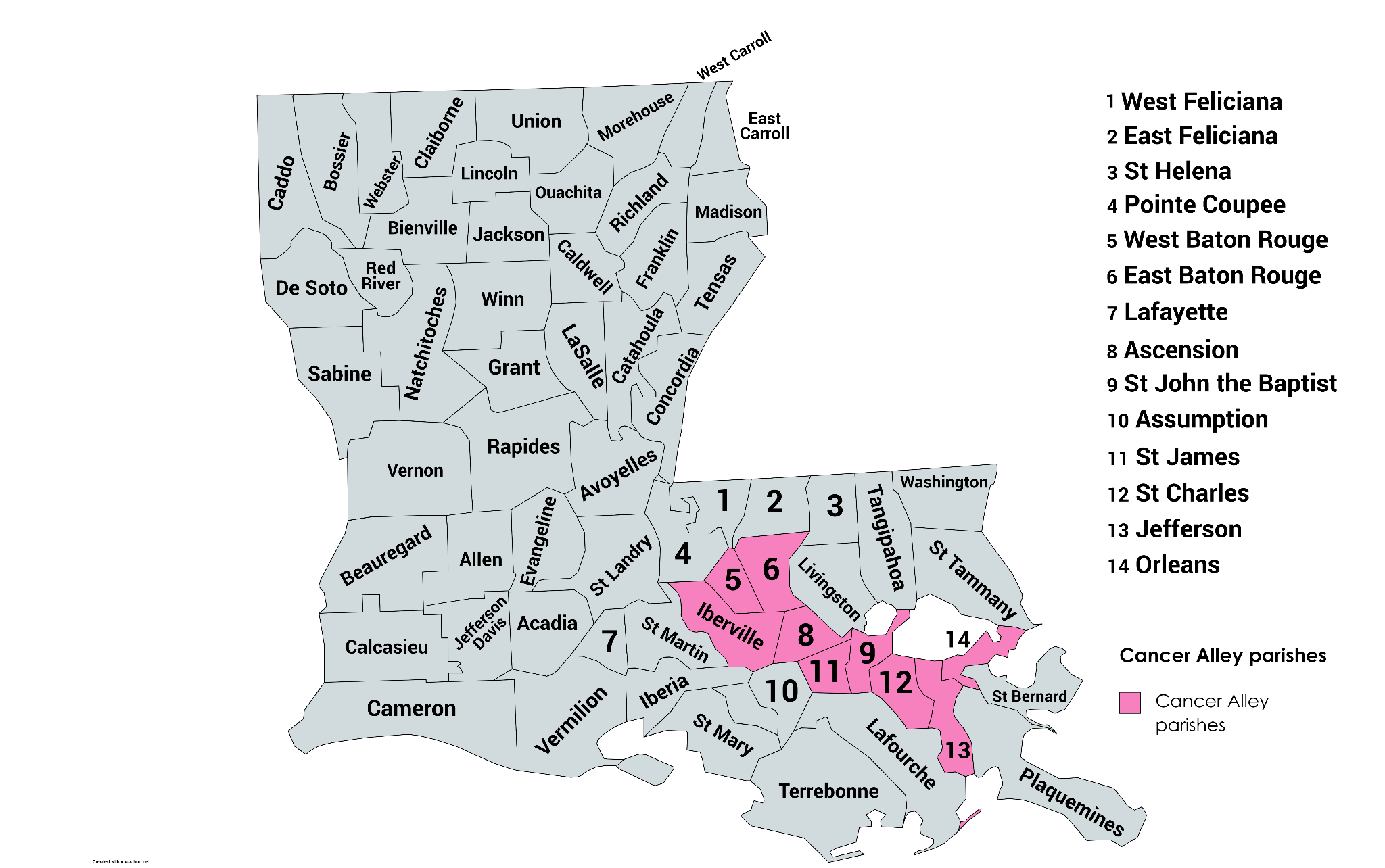

The Port of South Louisiana is located along the Mississippi River in Louisiana between Baton Rouge and New Orleans, Louisiana. This area is the River Parishes, which consists of St. James, St. John the Baptist, and St. Charles Parishes from east to west. The port ranks first in total domestic trade in the United States. Trade imports include over 50% of all the nation’s grain exports, million short tons of maize, soybean, animal feed, and wheat, and 67% of petroleum imports. These facts are some of the economic and international benefits. However, any damages or negative impacts at this port could impact the nation’s economy. Near this stretch of the Mississippi River are two of the significant highways in the state: Interstates 10 (I-10) and 55 (I-55). Along I-10 are numerous neighboring communities and commercial and industrial businesses. Figure 11.7 highlights the parishes referred to as the Cancer Alley parishes.

Along Cancer Alley, there are approximately 200 industrial facilities, such as petrochemical plants and refineries. The population residing in these parishes is predominantly African American and economically disadvantaged. These residents are disproportionately diagnosed with cancer due to environmental pollution from the toxic air particles from the nearby petrochemical facilities. A research study conducted in 2012 explored the disparities in cancer risks from air pollution in Cancer Alley. The study acknowledged the low socioeconomic status (SES) of the Cancer Alley residents tabulated by the high poverty and low literacy levels. The “racial makeup of Cancer Alley is 55% white and 40% black compared to state averages of 64% and 32%, national averages of 75% and 12%, respectively” (James et al., 2012). The study highlighted the contributing quantities of different chemical sources to the environment. The study revealed SES played a role in exacerbating the disparities.

Government interference led to reduced emissions of chemicals to a safe level set by the EPA. However, environmental activists and residents continue to fight for environmental equity. In September 2022, a legal ruling blocked the construction of the petrochemical plant, Formosa Plastics in St. James Parish. Future court appeals may alter future plant construction.

Addressing Environmental Injustices

It is critical to support community engagement and empowerment for environmental issues. It is also important to give residents a voice in policy and decision-making as a means to work with and not for them. Amplifying marginalized voices and promoting inclusive environmental planning would create a collaborative network between residents and political leaders. An educated community can advocate for themselves and generations to come.

In 1994, President William “Bill” Clinton signed Executive Order 12898, Federal Actions to Address Environmental Justice in Minority Populations and Low-Income Populations. This order required governmental agencies to focus on their decision-making impacts as they worked toward “the goal of achieving environmental protection for all communities” (United States Environmental Protection Agency, 2023 January). The order specifically focused on the implementation and creation of the Federal Interagency Working Group, which includes over a dozen federal agencies and heads of agencies that follow seven overarching guidelines.

Figure 11.8 shows the start and end of Executive Order 12898. The top image shows the date and order information in the federal register. The bottom image shows the presidential signature. Follow this link for the detailed executive order: https://www.archives.gov/files/federal-register/executive-orders/pdf/12898.pdf.

As an additional measure to support the need for environmental justice, the EPA created the Environmental Justice Screening Tool (EJScreen) that combines environmental and demographic indicators across the United States in maps and reports. The EJScreen tool provides data supporting the need for outreach and informing the public on public health concerns. Visit this website to find the EJScreen software: https://www.epa.gov/ejscreen.

Another approach to solving environmental injustices is the conversion from nonrenewable energy sources to Green Energy practices discussed in Chapter 4. This shift reduces emissions and environmental health impacts on surrounding communities.

Chapter Summary

Environmental ethics is imperative to achieving environmental safety for everyone. There are different ethical approaches to how the world’s resources are used in environmental science, such as frontier, sustainable, and land ethics. The frontier ethic is anthropocentric and utilizes resources for human benefit. The sustainable ethic acknowledges the limitation of resources in promoting sustainability for present and future generations. The land ethic is inclusive of everything present on earth. This approach considers all matter and organisms as important to an ecosystem. However, as environmental ethics is a subset of applied ethics, it will be interesting to see the overlapping impacts of other ethical domains (i.e., AI and business ethics).

The existing worldviews in environmental science demonstrate the interactions between humans and the natural world. Table 11.1 highlights the characteristics of five environmental science worldviews. Section 11.1 delves into two case studies. The Hetch Hetchy Valley case study considers ethical debates proposed in 1913 among groups debating to farm the valley for a concrete water supply. The Tragedy of the Commons acknowledges the economic principle of exploring resource use and preservation.

Environmental equity explores the need for equitable practices as opposed to equality. Environmental equity was acknowledged as a national concern that needed additional federal support. The US Office of Environmental Justice (formerly the US Office of Environmental Equity) was placed on the forefront in 1992. President Bill Clinton’s Executive Order 12898 cemented the Interagency Working Group that oversees sustaining positive environmental health for all but primarily minority and low-income populations.

Section 11.3 addressed the inequities experienced by indigenous people in the United States, residents of Flint, Michigan, and Louisiana residents in Cancer Alley. Each community experienced failures in government regulation, but these issues have been remedied while other communities remain in an ongoing quest for equity in vulnerable communities.

Several local, state, national, and global initiatives have been undertaken over the last thirty years to address environmental ethics, justice, and health.

Review Questions

- What are examples of applied ethics?

- What are the differences between land, sustainable, and frontier ethics?

- Compare the five worldviews. How do the biocentric and frontier worldviews differ?

- What are some long-term health impacts from the environmental racism discussion of hazardous waste sites?

- What roles or missing roles did governmental agencies play in the three vulnerable communities in section 11.3?

Critical Thinking / Questions for Discussion

- As we navigate the fourth industrial revolution (i.e., digital transformation and human-machine interactions), what do you perceive as potential impacts on the environment and public health?

- What do you think should have been the outcome of the Hetch Hetchy Valley case study? Do you agree or disagree with the damming of the valley?

- Which of the three vulnerable communities in section 11.3 resonated most with you?

Key Terms

- Applied ethics – the application of moral norms and principles to controversial issues to determine the rightness of specific actions.

- Environmental equity – the need for the fair treatment, safety, and protection of individuals from environmental hazards and disasters irrespective of their income and access to resources.

- Environmental ethics – an area of applied ethics that attempts to identify the right conduct in our relationship with the nonhuman world.

- Environmental justice – the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income concerning the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies.

- Frontier ethic – assumes that the earth has an unlimited supply of resources for human exploitation.

- Indigenous people – individuals who have a historical connection with their community and exist distinctly from other communities.

- Land ethic – inclusive of everything composed of matter including the soil, waters, plants, and animals.

- Legionnaires disease (also known as legionellosis) – is caused by the bacterium, Legionella pneumophila, and is found in contaminated water and cooling towers in air conditioning units. The first case of Legionnaires’ disease

- Sustainable ethic – an environmental ethic by which people treat the earth as if its resources are limited

- Tragedy of the commons – frequent economic and social framework on human behavior with shared resources.

References Cited

Cancer Alley. (2023, September 6). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cancer_Alley#cite_note-

Encyclopedia.com. (2019). Cancer alley, Louisiana. https://www.encyclopedia.com/environment/educational-magazines/cancer-alley-louisiana#:~:text=The%20population%20of%20cancer%20alley,not%20have%20a%20college%20education

EPA’s Environmental Justice Screening and Mapping Tool. (2023). EJ screen. Retrieved September 6, 2023. https://ejscreen.epa.gov/mapper/

Fisher, M. R. (2017). Environmental biology. Pressbooks. https://openoregon.pressbooks.pub/envirobiology/chapter/1-4-environmental-ethics/

Greenlaw, S. A., Shapiro, D., & MacDonald, D. (2023). Principles of economics 3e. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/details/books/principles-economics-3e

James, W., Chunrong, J., & Kedia, S. (2012). Uneven magnitude of disparities in cancer risks from air toxics. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 9(12), 4365–4385. doi:10.3390/ijerph9124365

Kamala, D. (2017). 2.1 Environment and sustainability. Flexbooks. https://www.ck12.org/user%3azg9yc25lckbnbwfpbc5jb20./book/essentials-of-environmental-science/section/2.1/

Loyola University New Orleans. (2023). JustSouth publications. https://jsri.loyno.edu/publications

Maaravi, Y., Levy, A., Gur, T., Confino, D., & Segal, S. (2021). “The tragedy of the commons”: How individualism and collectivism affected the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Public Health, 9, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.627559

Port of South Louisiana. (2023). Facts at a glance. https://portsl.com/facts-at-a-glance/

Saylor Academy. (2023). ENVS203: Environmental ethics, justice, and world views’. [Massive open online course]. Constitution Foundation. https://learn.saylor.org/course/view.php?id=2

Smith, N. (2023). Introduction to philosophy. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/introduction-philosophy/pages/10-2-environmental-ethics

United Nations. (2004). Workshop on data collection and disaggregation for indigenous peoples. https://view.officeapps.live.com/op/view.aspx?src=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.un.org%2Fesa%2Fsocdev%2Funpfii%2Fdocuments%2Fworkshop_data_background.doc%23%3A~%3Atext%3D%25E2%2580%259CIndigenous%2520communities%252C%2520peoples%2520and%2520nations%2520are%2520those%2520which%252C%2520having%2Cterritories%252C%2520or%2520parts%2520of%2520them.&wdOrigin=BROWSELINK

United States Energy Information Administration. (2023). How much gasoline does the United States consume? EIA. https://www.eia.gov/tools/faqs/faq.php?id=23&t=10

United States Environmental Protection Agency. (2023, January 30). How was EJScreen developed? https://www.epa.gov/ejscreen/how-was-ejscreen-developed

United States Environmental Protection Agency. (2023, August 16). Learn about environmental justice. https://www.epa.gov/environmentaljustice/learn-about-environmental-justice#eo12898

Recommended Reading

Blankenbuehler, P. (2016, May 30). Why Hetch Hetchy is staying under water. High Country News. https://www.hcn.org/issues/48.9/why-hetch-hetchy-is-staying-under-water

Campbell, C., Greenberg, R., Mankikar, D., & Ross, R. D. (2016). A case study of environmental injustice: The failure in Flint. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 13(10), 1–11. doi: 10.3390/ijerph13100951

Miller, E. (2017). Flint water crisis: A turning point for environmental justice. WOSU Public Media. https://news.wosu.org/news/2017-09-21/flint-water-crisis-a-turning-point-for-environmental-justice#stream/0

Patil, A. (2023, August 29). Wildfires burn across Louisiana, killing 2. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/08/29/us/louisiana-wildfires-tiger-island.html

Winters, J. (2022, September 16). A win for residents of ‘Cancer Alley.’ Grist. https://grist.org/beacon/a-win-for-residents-of-cancer-alley/

Teacher Activities

Castrigano, D. & Pockl, L. (2023, September 15). A look at Cancer Alley, Louisiana. Subject to Climate Change. https://subjecttoclimate.org/lesson-plan/a-look-at-cancer-alley-louisiana

These deal with the responsibilities of the present human generation to ensure continued access to adequate resources and livelihoods for future generations of people and other species.