4.2 Chain of Infection

Myra Sandquist Reuter, MA, BSN, RN - Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

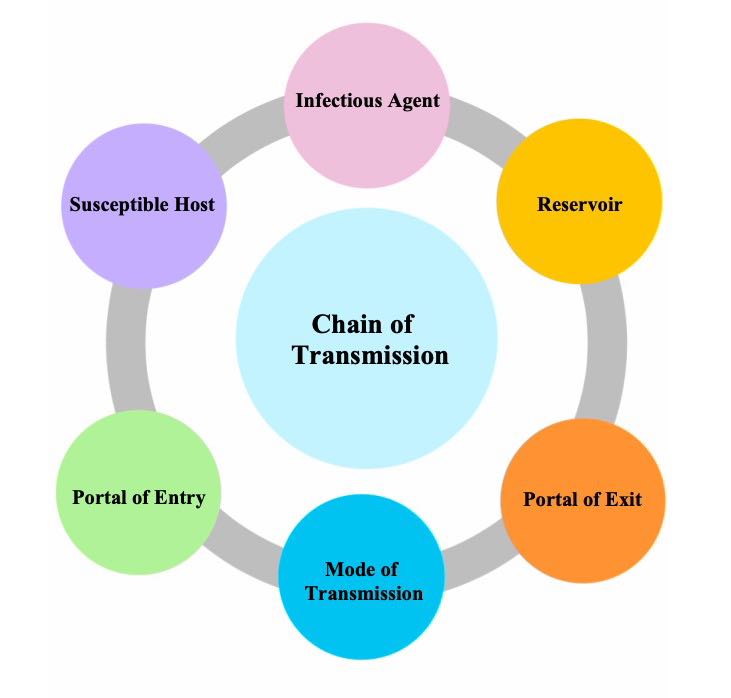

The chain of infection, also referred to as the chain of transmission, describes how an infection spreads based on these six links of transmission:

- Infectious Agent

- Reservoirs

- Portal of Exit

- Modes of Transmission

- Portal of Entry

- Susceptible Host

See Figure 4.1[1] for an illustration of the chain of infection. If any “link” in the chain of infection is removed or neutralized, transmission of infection will not occur. Health care workers must understand how an infectious agent spreads via the chain of transmission so they can break the chain and prevent the transmission of infectious disease. Routine hygienic practices, standard precautions, and transmission-based precautions are used to break the chain of transmission.

The links in the chain of infection include Infectious Agent, Reservoir, Portal of Exit, Mode of Transmission, Portal of Entry, and Susceptible Host[2]:

- Infectious Agent: Microorganisms, such as bacteria, viruses, fungi, or parasites, that can cause infectious disease.

- Reservoir: The host in which infectious agents live, grow, and multiply. Humans, animals, and the environment can be reservoirs. Examples of reservoirs are a person with a common cold, a dog with rabies, or standing water with bacteria. Sometimes a person may carry an infectious agent but is not symptomatic or ill. This is referred to as being colonized, and the person is referred to as a carrier. For example, many health care workers carry methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) bacteria in their noses but are not symptomatic.

- Portal of Exit: The route by which an infectious agent escapes or leaves the reservoir. In humans, the portal of exit is typically a mucous membrane or other opening in the skin. For example, pathogens that cause respiratory diseases usually escape through a person’s nose or mouth.

- Mode of Transmission: The way in which an infectious agent travels to other people and places because they cannot travel on their own. Modes of transmission include contact, droplet, or airborne transmission. For example, touching sheets with drainage from one person’s infected wound and then touching another person without washing one’s hands is an example of contact transmission of an infectious agent. Examples of droplet or airborne transmission are coughing and sneezing, depending on the size of the microorganism.

- Portal of Entry: The route by which an infectious agent enters a new host (i.e., the reverse of the portal of exit). For example, mucous membranes, skin breakdown, and artificial openings in the skin created for the insertion of medical equipment (such as intravenous lines) are at high risk for infection because they provide an open path for microorganisms to enter the body. Tubes inserted into mucous membranes, such as a urinary catheter, also facilitate the entrance of microorganisms into the body. A person’s immune system fights against infectious organisms that have entered the body through the use of nonspecific and specific defenses. Read more about defenses against microorganisms in the “Defenses Against Transmission of Infection” section of this chapter.

- Susceptible Host: A person at elevated risk for developing an infection when exposed to an infectious agent due to changes in their immune system defenses. For example, infants (up to 2 years old) and older adults (aged 65 or older) are at higher risk for developing infections due to underdeveloped or weakened immune systems. Additionally, anyone with chronic medical conditions (such as diabetes) are also at higher risk of developing an infection. In health care settings, almost every patient is considered a “susceptible host” because of preexisting illnesses, medical treatments, medical devices, or medications that increase their vulnerability to developing an infection when exposed to infectious agents in the health care environment. As caregivers, it is the NA’s responsibility to protect susceptible patients by breaking the chain of infection.

After a susceptible host becomes infected, they become a reservoir that can then transmit the infectious agent to another person. If an individual’s immune system successfully fights off the infectious agent, they may not develop an infection, but instead the person may become an asymptomatic “carrier” who can spread the infectious agent to another susceptible host. For example, individuals exposed to COVID-19 may not develop an active respiratory infection but can spread the virus to other susceptible hosts via sneezing.

Learn more about the chain of infection by clicking on the following activities.

This H5P activity is a derivative of original activities by Michelle Hugues and licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0 unless otherwise noted.

This H5P activity is a derivative of original activities by Michelle Hugues and licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0 unless otherwise noted.

This H5P activity is a derivative of original activities by Michelle Hugues and licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0 unless otherwise noted.

This H5P activity is a derivative of original activities by Michelle Hugues and licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0 unless otherwise noted.

This H5P activity is a derivative of original activities by Michelle Hugues and licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0 unless otherwise noted.

This H5P activity is a derivative of original activities by Michelle Hugues and licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0 unless otherwise noted.

Putting It All Together

Note: To enlarge the print, you can expand the activity by clicking the arrows in the right upper corner of the text box. Please drag and drop the descriptors and actions into the appropriate boxes to demonstrate the various steps in the chain of infection.

This H5P activity is a derivative of original activities by Michelle Hugues and licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0 unless otherwise noted.

Healthcare-Acquired Infections

An infection that develops in an individual after being admitted to a health care facility or undergoing a medical procedure is a healthcare-associated infection (HAI), formerly referred to as a nosocomial infection. About 1 in 31 hospital patients develops at least one healthcare-associated infection every day. HAIs increase the cost of care and delay recovery. They are associated with permanent disability, loss of wages, and even death. An example of an HAI is a skin infection that develops in a patient’s incision after they had surgery due to improper hand hygiene of health care workers.[3],[4] It is important to understand the dangers of Healthcare-Acquired Infections and actions that can be taken to prevent them.

Read more details about healthcare-acquired infections in the “Infection” chapter of Open RN Nursing Fundamentals.

Healthcare-Associated Infections by Michelle Hughes is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Media Attributions

- Chain-of-Transmission

- “Chain-of-Transmission” by unknown author is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0. Access for free at https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/introductiontoipcp/chapter/40/ ↵

- Department of Health. (n.d.). Chain of infection in infection prevention and control (IPAC). The Government of Nunavut. https://www.gov.nu.ca/health/information/infection-prevention-and-control ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Fundamentals by Chippewa Valley Technical College and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Office of Infectious Disease and HIV/AIDS Policy. (n.d.). Health care-associated infections. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. https://www.hhs.gov/oidp/topics/health-care-associated-infections/index.html ↵

Also referred to as the chain of transmission, describes how an infection spreads based on these six links of transmission: infectious agent, reservoirs, portal of exit, modes of transmission, portal of entry, and susceptible host.

Microorganisms, such as bacteria, viruses, fungi, or parasites, that can cause infectious disease.

Learning Activities

(Answers to “Learning Activities” can be found in the “Answer Key” at the end of the book. Answers to interactive activity elements will be provided within the element as immediate feedback.)

Scenario A

A nurse is caring for a client who has been hospitalized after undergoing hip-replacement surgery. The client complains of not sleeping well and feels very drowsy during the day.

- What factors are affecting the client’s sleep pattern?

- What assessments should the nurse perform?

- What SMART outcome can be established for this client?

- Outline interventions the nurse can implement to enhance sleep for this client.

- How will the nurse evaluate if the interventions are effective?

Scenario B

A nurse is assigned to work rotating shifts and develops difficulty sleeping.

- Why do rotating shifts affect a person’s sleep pattern?

- What are the symptoms of insomnia?

- Describe healthy sleep habits the nurse can adopt for more restful sleep.

Test your knowledge using this NCLEX Next Generation-style bowtie question. You may reset and resubmit your answers to this question an unlimited number of times.[1]

Circadian rhythms: Body rhythms that direct a wide variety of functions, including wakefulness, body temperature, metabolism, and the release of hormones. They control the timing of sleep, causing individuals to feel sleepy at night and creating a tendency to wake in the morning without an alarm. (Chapter 12.2)

Insomnia: A common sleep disorder that causes trouble falling asleep, staying asleep, or getting good quality sleep. Insomnia interferes with daily activities and causes the person to feel unrested or sleepy during the day. Short-term insomnia may be caused by stress or changes in one’s schedule or environment, lasting a few days or weeks. Chronic insomnia occurs three or more nights a week, lasts more than three months, and cannot be fully explained by another health problem or a medicine. Chronic insomnia raises the risk of high blood pressure, coronary heart disease, diabetes, and cancer. (Chapter 12.2)

Microsleep: Brief moments of sleep that occur when a person is awake. A person can't control microsleep and might not be aware of it. (Chapter 12.2)

Narcolepsy: An uncommon sleep disorder that causes periods of extreme daytime sleepiness and sudden, brief episodes of deep sleep during the day. (Chapter 12.2)

Non-REM sleep: Slow-wave sleep when restoration takes place and the body’s temperature, heart rate, and oxygen consumption decrease. (Chapter 12.2)

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA): A common sleep condition that occurs when the upper airway becomes repeatedly blocked during sleep, reducing or completely stopping airflow. If the brain does not send the signals needed to breathe, the condition may be called central sleep apnea. (Chapter 12.2)

REM sleep: Rapid eye movement (REM) sleep when heart rate and respiratory rate increase, eyes twitch, and brain activity increases. Dreaming occurs during REM sleep, and muscles become limp to prevent acting out one’s dreams. (Chapter 12.2)

Sleep diary: A record of the time a person goes to sleep, wakes up, and takes naps each day for 1-2 weeks. Timing of activities such as exercising and drinking caffeine or alcohol are also recorded, as well as feelings of sleepiness throughout the day. (Chapter 12.2)

Sleep study: A diagnostic test that monitors and records data during a client’s full night of sleep. A sleep study may be performed at a sleep center or at home with a portable diagnostic device. (Chapter 12.2)

Sleep-wake homeostasis: The homeostatic sleep drive keeps track of the need for sleep, reminds the body to sleep after a certain time, and regulates sleep intensity. This sleep drive gets stronger every hour a person is awake and causes individuals to sleep longer and more deeply after a period of sleep deprivation. (Chapter 12.2)

Circadian rhythms: Body rhythms that direct a wide variety of functions, including wakefulness, body temperature, metabolism, and the release of hormones. They control the timing of sleep, causing individuals to feel sleepy at night and creating a tendency to wake in the morning without an alarm. (Chapter 12.2)

Insomnia: A common sleep disorder that causes trouble falling asleep, staying asleep, or getting good quality sleep. Insomnia interferes with daily activities and causes the person to feel unrested or sleepy during the day. Short-term insomnia may be caused by stress or changes in one’s schedule or environment, lasting a few days or weeks. Chronic insomnia occurs three or more nights a week, lasts more than three months, and cannot be fully explained by another health problem or a medicine. Chronic insomnia raises the risk of high blood pressure, coronary heart disease, diabetes, and cancer. (Chapter 12.2)

Microsleep: Brief moments of sleep that occur when a person is awake. A person can't control microsleep and might not be aware of it. (Chapter 12.2)

Narcolepsy: An uncommon sleep disorder that causes periods of extreme daytime sleepiness and sudden, brief episodes of deep sleep during the day. (Chapter 12.2)

Non-REM sleep: Slow-wave sleep when restoration takes place and the body’s temperature, heart rate, and oxygen consumption decrease. (Chapter 12.2)

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA): A common sleep condition that occurs when the upper airway becomes repeatedly blocked during sleep, reducing or completely stopping airflow. If the brain does not send the signals needed to breathe, the condition may be called central sleep apnea. (Chapter 12.2)

REM sleep: Rapid eye movement (REM) sleep when heart rate and respiratory rate increase, eyes twitch, and brain activity increases. Dreaming occurs during REM sleep, and muscles become limp to prevent acting out one’s dreams. (Chapter 12.2)

Sleep diary: A record of the time a person goes to sleep, wakes up, and takes naps each day for 1-2 weeks. Timing of activities such as exercising and drinking caffeine or alcohol are also recorded, as well as feelings of sleepiness throughout the day. (Chapter 12.2)

Sleep study: A diagnostic test that monitors and records data during a client’s full night of sleep. A sleep study may be performed at a sleep center or at home with a portable diagnostic device. (Chapter 12.2)

Sleep-wake homeostasis: The homeostatic sleep drive keeps track of the need for sleep, reminds the body to sleep after a certain time, and regulates sleep intensity. This sleep drive gets stronger every hour a person is awake and causes individuals to sleep longer and more deeply after a period of sleep deprivation. (Chapter 12.2)

Learning Objectives

- Identify factors putting clients at risk for mobility problems

- Identify cues related to mobility problems

- Identify the effects of immobility on body systems

- Describe nursing interventions to prevent complications of immobility

- Contribute to a plan of care for clients with mobility alterations

Sit on a sturdy chair with your legs and arms stretched out in front of you, and then try to stand. This basic mobility task can be impaired during recovery from major surgery or for clients with chronic musculoskeletal conditions. Mobility, which includes moving one’s extremities, changing positions, sitting, standing, and walking, helps avoid degradation of many body systems and prevents complications associated with immobility. Nurses assist clients to be as mobile as possible, based on their individual circumstances, to achieve their highest level of independence, prevent complications, and promote a feeling of well-being. This chapter will discuss nursing assessments and interventions related to promoting mobility.

Learning Objectives

- Identify factors putting clients at risk for mobility problems

- Identify cues related to mobility problems

- Identify the effects of immobility on body systems

- Describe nursing interventions to prevent complications of immobility

- Contribute to a plan of care for clients with mobility alterations

Sit on a sturdy chair with your legs and arms stretched out in front of you, and then try to stand. This basic mobility task can be impaired during recovery from major surgery or for clients with chronic musculoskeletal conditions. Mobility, which includes moving one’s extremities, changing positions, sitting, standing, and walking, helps avoid degradation of many body systems and prevents complications associated with immobility. Nurses assist clients to be as mobile as possible, based on their individual circumstances, to achieve their highest level of independence, prevent complications, and promote a feeling of well-being. This chapter will discuss nursing assessments and interventions related to promoting mobility.