4.4 Diagnosis

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

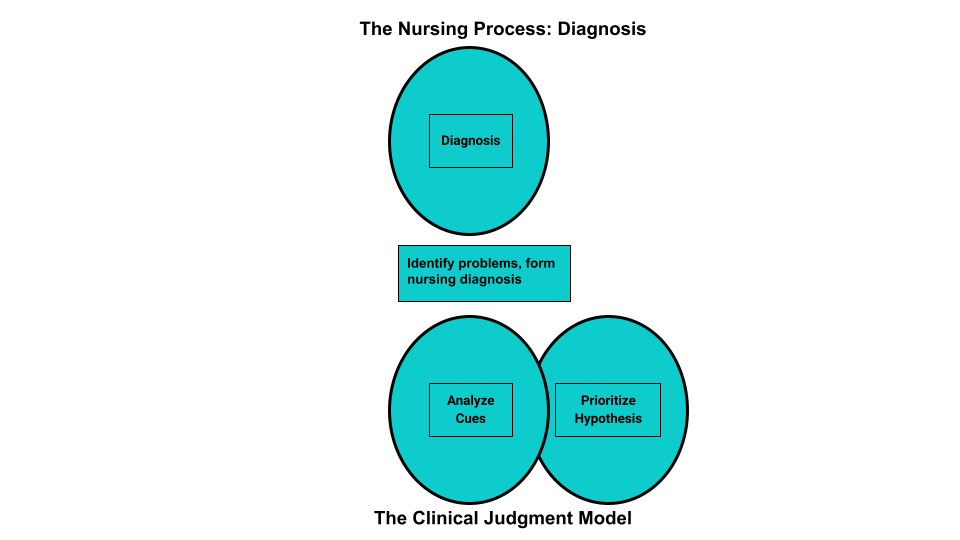

Diagnosis is the second step of the nursing process (and the second Standard of Practice by the American Nurses Association). This standard is defined as, “The registered nurse analyzes assessment data to determine actual or potential diagnoses, problems, and issues.” The RN “prioritizes diagnoses, problems, and issues based on mutually established goals to meet the needs of the health care consumer across the health–illness continuum and the care continuum.” Diagnoses, problems, strengths, and issues are documented in a manner that facilitates the development of expected outcomes and a collaborative plan.[1] See Figure 4.7a for an illustration of how the Diagnosis phase of the nursing process corresponds to the NCSBN Clinical Judgment Measurement Model (NCJMM).[2]

Analyzing Assessment Data

After collection of assessment data, the RN analyzes the data to form generalizations and create and prioritize hypotheses for nursing diagnoses. Steps for analyzing assessment data include performing data analysis, clustering information, identifying hypotheses for potential nursing diagnosis, performing additional in-depth assessment as needed, and establishing nursing diagnosis statements. The nursing diagnoses are then prioritized and the nursing care plan is developed based on them.[3] Analyzing assessment data is completed by an RN and falls outside of the scope of practice of the LPN/VN. However, LPN/VNs must understand data analysis so that new, concerning data is promptly reported to the RN for follow-up.

Performing Data Analysis

After nurses collect assessment data from a client, they use their nursing knowledge to analyze that data to determine if it is “expected” or “unexpected” or “normal” or “abnormal” for that client according to their age, development, and baseline status. From there, nurses determine what data is “clinically relevant” as they prioritize their nursing care.[4]

Example of Analyzing Cues

In Scenario C in the “Assessment” section of this chapter, the nurse analyzes the vital signs data and determines the blood pressure, heart rate, and respiratory rate are elevated, and the oxygen saturation is decreased for this client. These findings are considered “relevant cues” because they are abnormal compared to this client’s baseline and may indicate a new health problem or complication is occurring.

Clustering Information/Seeing Patterns/Making Hypotheses

After analyzing the data and determining relevant cues, the nurse begins clustering data into similar domains or patterns. Evidence-based assessment frameworks, such as Gordon’s Functional Health Patterns, assist nurses in clustering data based on patterns of human responses. See the box below for an outline of Gordon’s Functional Health Patterns.[5] Concepts related to many of these patterns will be discussed in chapters later in this book.

Gordon’s Functional Health Patterns[6]

Health Perception-Health Management: A client’s perception of their health and well-being and how it is managed

Nutritional-Metabolic: Food and fluid consumption relative to metabolic need

Elimination: Excretory function, including bowel, bladder, and skin

Activity-Exercise: Exercise and daily activities

Sleep-Rest: Sleep, rest, and daily activities

Cognitive-Perceptual: Perception and cognition

Self-perception and Self-concept: Self-concept and perception of self-worth, self-competency, body image, and mood state

Role-Relationship: Role engagements and relationships

Sexuality-Reproductive: Reproduction and satisfaction or dissatisfaction with sexuality

Coping-Stress Tolerance: Coping and effectiveness in terms of stress tolerance

Value-Belief: Values, beliefs (including spiritual beliefs), and goals that guide choices and decisions

Example of Using Gordon’s Health Patterns to Cluster Data

Refer to Scenario C in the “Assessment” section of this chapter. The nurse clusters the following relevant cues: elevated blood pressure, elevated respiratory rate, crackles in the lungs, weight gain, worsening edema, shortness of breath, medical history of heart failure, and currently prescribed a diuretic medication into a pattern of fluid balance, which can be classified under Gordon’s Nutritional-Metabolic Functional Health Pattern. Based on the related data in this cluster, the nurse makes a hypothesis that the client has excess fluid volume present.

Identifying Nursing Diagnoses

After the nurse has analyzed and clustered the data from the client assessment, the next step is to begin to answer the question, “What are my client’s human responses to their health condition(s) (i.e., their nursing diagnoses)?” A nursing diagnosis is defined as, “A clinical judgment concerning a human response to health conditions/life processes, or susceptibility to that response, by an individual, caregiver, family, group, or community.”[7] Nursing diagnoses are customized to each client and drive the development of the nursing care plan. The nurse should refer to a care planning resource and review the definitions and defining characteristics of the hypothesized nursing diagnoses to determine if additional in-depth assessment is needed before selecting the most accurate nursing diagnosis. Formulation of nursing diagnoses is completed by an RN and is outside the scope of practice of LPN/VNs.

Nursing diagnoses are developed by nurses, for use by nurses. For example, NANDA International (NANDA-I) is a global professional nursing organization that develops nursing terminology that names actual or potential human responses to health problems and life processes based on research findings. Currently, there are over 220 NANDA-I nursing diagnoses developed by nurses around the world. This list is continuously updated, with new nursing diagnoses added and old nursing diagnoses retired that no longer have supporting evidence.[8] A list of commonly used NANDA-I diagnoses is listed in Appendix A. For a full list of NANDA-I nursing diagnoses, refer to a current nursing care plan reference.

NANDA-I nursing diagnoses are grouped into 13 domains that assist the nurse in selecting diagnoses based on the patterns of clustered data. These domains are similar to Gordon’s Functional Health Patterns and include health promotion, nutrition, elimination and exchange, activity/rest, perception/cognition, self-perception, role relationship, sexuality, coping/stress tolerance, life principles, safety/protection, comfort, and growth/development.

NANDA Diagnoses and the NCLEX

Knowledge regarding specific NANDA-I nursing diagnoses is not assessed on the NCLEX. However, analyzing cues, clustering data, forming appropriate hypotheses, and prioritizing hypotheses are components of clinical judgment assessed on the NCLEX and used in nursing practice. Read more about the Next Generation NCLEX in the “Scope of Practice” chapter.

Nursing Diagnoses vs. Medical Diagnoses

You may be asking yourself, “How are nursing diagnoses different from medical diagnoses?” Medical diagnoses focus on diseases or other medical problems that have been identified by the physician, physician’s assistant, or advanced nurse practitioner. Nursing diagnoses focus on the human response to health conditions and life processes and are made independently by RNs. Clients with the same medical diagnosis will often respond differently to that diagnosis and thus have different nursing diagnoses. For example, two clients have the same medical diagnosis of heart failure. However, one client may be interested in learning more information about the condition and the medications used to treat it, whereas another client may be experiencing anxiety when thinking about the effects this medical diagnosis will have on their family. The nurse must consider these different responses when creating the nursing care plan. Nursing diagnoses consider the client’s and family’s needs, attitudes, strengths, challenges, and resources as a customized nursing care plan is created to provide holistic and individualized care for each client.

Example of a Medical Diagnosis

A medical diagnosis identified for Ms. J. in Scenario C in the “Assessment” section is heart failure. This cannot be used as a nursing diagnosis because it is outside the nurse’s scope of practice to make a medical diagnosis, but it is considered as an “associated condition” when creating hypotheses for nursing diagnoses. Associated conditions are medical diagnoses, injuries, procedures, medical devices, or pharmacological agents that are not independently modifiable by the nurse, but support accuracy in nursing diagnosis. The nursing diagnosis in Scenario C will relate to the client’s responses to her medical diagnosis of heart failure, such as “Excess Fluid Volume.”

Additional Definitions Used in NANDA-I Nursing Diagnoses

The following definitions are used in association with NANDA-I nursing diagnoses.

Patient

The NANDA-I definition of a “patient” includes the following:[9]

- Individual: a single human being distinct from others (i.e., a person).

- Caregiver: a family member or helper who regularly looks after a child or a sick, elderly, or disabled person.

- Family: two or more people having continuous or sustained relationships, perceiving reciprocal obligations, sensing common meaning, and sharing certain obligations toward others; related by blood and/or choice.

- Group: a number of people with shared characteristics

- Community: a group of people living in the same locale under the same governance, such as neighborhoods and cities.

Age

The age of the person who is the subject of the diagnosis is defined by the following terms:[10]

- Fetus: an unborn human more than eight weeks after conception, until birth.

- Neonate: a person less than 28 days of age.

- Infant: a person greater than 28 days and less than 1 year of age.

- Child: a person less than or equal to 19 years of age, unless national law defines a person to be an adult at an earlier age

- Adolescent: a person aged 10 to 19 years.

- Adult: a person older than 19 years of age unless national law defines a person as being an adult at an earlier age.

- Older adult: a person 65-84 years of age.

- Aged adult: Person 85 years or older.

Time

The duration of the diagnosis is defined by the following terms:[11]

- Acute: lasting less than three months.

- Chronic: lasting greater than three months.

- Intermittent: stopping or starting again at intervals.

- Continuous: uninterrupted, going on without stop.

Two terms used to assist in creating nursing diagnosis statements are at-risk populations and associated conditions:[12]

- at-risk populations groups of people who share a sociodemographic characteristics, health/family history, stages of growth/development, exposure to certain events/experiences that cause each member to be susceptible to a particular human response. These characteristics are not modifiable by independent nursing interventions.

- Associated Conditions are medical diagnoses, diagnostic/surgical procedures, medical/surgical devices, or pharmaceutical preparations. These conditions are not modifiable by independent nursing interventions.

Types of Nursing Diagnoses

There are four types of NANDA-I nursing diagnoses:[13]

- Problem-Focused

- Health Promotion

- Risk

- Syndrome

A problem-focused nursing diagnosis is a clinical judgment concerning an undesirable human response to health conditions/life processes that is recognized in an individual, caregiver, family, group, or community.[14]

To make an accurate problem-focused diagnosis, related factors and defining characteristics must be present. Related factors (also called etiology) are antecedent factors shown to have a partnered relationship with the human response. These factors must be modifiable by independent nursing interventions, and whenever possible, interventions should be aimed at these etiological factors Problem-focused and syndromes must have related factors; health promotion diagnoses may have related factors if they help clarify the diagnosis.[15]

Defining characteristics are observable cues or inferences that cluster as manifestations of a problem-focused diagnosis, health promotion diagnosis, or syndrome. Defining characteristics refer to things a nurse can see, hear, touch, or smell.[16]

A health promotion nursing diagnosis is a clinical judgment concerning motivation and desire to increase well-being and to actualize human health potential that is recognized in an individual, caregiver, family, group, or community. These responses are expressed by the client’s readiness to enhance specific health behaviors. In individuals who are unable to express their own readiness to enhance health behaviors, the nurse may determine a condition for health promotion exists and act on the client’s behalf. To make a health promotion nursing diagnosis, defining characteristics must be present.[17]

A risk nursing diagnosis is a clinical judgment concerning the susceptibility for developing an undesirable human response to health conditions/life processes that is recognized in an individual, caregiver, family, group, or community. To make a risk nursing diagnosis, risk factors must be present that contribute to increased susceptibility.[18] A risk nursing diagnosis is different from the problem-focused diagnosis in that the problem has not yet actually occurred. However, problem diagnoses should not be automatically viewed as more important than risk diagnoses because sometimes a risk diagnosis can have the highest priority for a client.

A syndrome nursing diagnosis is a clinical judgment concerning a specific cluster of nursing diagnoses that occur together and are best addressed together and through similar interventions. To make a syndrome nursing diagnosis, defining characteristics must include two or more nursing diagnosis and related factors.[19]

Establishing Nursing Diagnosis Statements

NANDA-I recommends creating statements for nursing diagnosis that include the nursing diagnosis and related factors as exhibited by defining characteristics. The accuracy of the nursing diagnosis is validated when a nurse is able to clearly link the defining characteristics, related factors, and/or risk factors found during the client’s assessment.[20]

To create a nursing diagnosis statement, the nurse analyzes the client’s subjective and objective data and clusters the data into patterns. Based on these patterns, the nurse generates hypotheses for nursing diagnoses based on how the patterns meet defining characteristics of a nursing diagnosis. Recall that “defining characteristics” are the signs and symptoms related to a nursing diagnosis. Defining characteristics are included in care planning resources for each nursing diagnosis, along with a definition of that diagnosis, so the nurse can select the most accurate diagnosis.

Example

The nurse clusters objective and subjective data such as weight, height, and dietary intake as a pattern related to nutritional status and then compares these signs and symptoms to the defining characteristics for the NANDA nursing diagnosis, “Imbalanced Nutrition: Less Than Body Requirement.”

When creating a nursing diagnosis statement, the nurse also identifies the cause, or etiology, of the problem for that specific client. Recall that the term “related factors” refers to the underlying causes (etiology) of a client’s problem or situation. Related factors should not refer to medical diagnoses, but instead should be causes that the nurse can treat. When possible, the nursing interventions planned for nursing diagnoses should attempt to modify or remove these underlying causes of the nursing diagnosis.

Creating nursing diagnosis statements is also called “using PES format.” The PES mnemonic no longer applies to the current terminology used by NANDA-I, but the components of a nursing diagnosis statement remain the same. A nursing diagnosis statement should contain the problem, related factors, and defining characteristics. These terms fit under the former PES format in this manner:

Problem (P): The problem (i.e., the nursing diagnosis)

Etiology (E): The related factors (i.e., the etiology/cause) of the nursing diagnosis; phrased as “related to” or “R/T”

Signs and Symptoms (S): The defining characteristics manifested by the client (i.e., the signs and symptoms/subjective and objective data/clinical cues) that led to the identification of that nursing diagnosis/hypothesis for the client; phrased with “as manifested by” (AMB) or “as evidenced by” (AEB).

Examples of different types of nursing diagnoses are further explained in the following sections.

Problem-Focused Nursing Diagnosis

A problem-focused nursing diagnosis contains all three components of the PES format:

Problem (P): Client problem (nursing diagnosis)

Etiology (E): Related factors causing the nursing diagnosis

Signs and Symptoms (S): Defining characteristics/cues manifested by that client (i.e., the signs and symptoms demonstrating there is a problem)

Example of a Problem-Focused Nursing Diagnosis

Refer to Scenario C of the “Assessment” section of this chapter. The cluster of data for Ms. J. (elevated blood pressure, elevated respiratory rate, crackles in the lungs, weight gain, worsening edema, and shortness of breath) are defining characteristics for the NANDA-I Nursing Diagnosis Excess Fluid Volume. The NANDA-I definition of Excess Fluid Volume is “surplus retention of fluid.” The related factor (etiology) of the problem is that the client has excessive fluid intake.[21]

The components of a problem-focused nursing diagnosis statement for Ms. J. would be:

Problem (P): Excess Fluid Volume

Etiology (E): Related to excessive fluid intake

Signs and Symptoms (S): As manifested by bilateral basilar crackles in the lungs, bilateral 2+ pitting edema of the ankles and feet, increased weight of 1ten pounds, and the client reports, “My ankles are so swollen.”

A correctly written problem-focused nursing diagnosis statement for Ms. J. would be written as follows:

Excess Fluid Volume related to excessive fluid intake as manifested by bilateral basilar crackles in the lungs, bilateral 2+ pitting edema of the ankles and feet, an increase weight of 1ten pounds, and the client reports, “My ankles are so swollen.”

Health-Promotion Nursing Diagnosis

A health-promotion nursing diagnosis statement contains the problem (P) and the defining characteristics (S). The defining characteristics component of a health-promotion nursing diagnosis statement should begin with the phrase “expresses desire to enhance,” followed by what the client states in relation to improving their health status:[22]

A health-promotion diagnosis statement consists of the following:

Problem (P): Client problem (nursing diagnosis)

Signs and Symptoms (S): The client’s expressed desire to enhance

Example of a Health-Promotion Nursing Diagnosis

Refer to Scenario C in the “Assessment” section of this chapter. Ms. J. demonstrates a readiness to improve her health status when she told the nurse that she would like to “learn more about my health so I can take better care of myself.” This statement is a defining characteristic of the NANDA-I nursing diagnosis Readiness for Enhanced Health Self-Management, which is defined as “a pattern of satisfactory management of symptoms, treatment regimen, physical, psychosocial, and spiritual consequences and lifestyle changes inherent in living with a chronic condition, which can be strengthened.”[23]

The components of a health-promotion nursing diagnosis for Ms. J. would be:

Problem (P): Readiness for Enhanced Health Self-Management

Symptoms (S): Expressed desire to “learn more about my treatment regimen so I can take better care of myself.”

A correctly written health-promotion nursing diagnosis statement for Ms. J. would be written as follows:

Enhanced Readiness for Health Promotion as manifested by expressed desire to “learn more about my treatment regimen so I can take better care of myself.”

Risk Nursing Diagnosis

A risk nursing diagnosis should be supported by evidence of the client’s risk factors for developing that problem. For example, the phrase “as evidenced by” is used to refer to the risk factors for developing that diagnosis.[24]

A risk diagnosis consists of the following:

Problem (P): Client problem (nursing diagnosis)

As Evidenced By: Risk factors for developing the problem

Example of a Risk Nursing Diagnosis

Refer to Scenario C in the “Assessment” section of this chapter. Ms. J. has an increased risk of falling due to weakness and fear of falling that she is experiencing. The NANDA-I definition of Risk for Adult Falls is “an adult susceptible to experiencing an event resulting in coming to rest inadvertently on the ground, floor, other level, which may compromise health.”[25]

The components of a risk nursing diagnosis statement for Ms. J. would be:

Problem (P): Risk for Adult Falls

As Evidenced By: Decreased lower extremity strength and fear of falling

A correctly written risk nursing diagnosis statement for Ms. J. would be written as follows:

Risk for Adult Falls as evidenced by decreased lower extremity strength and fear of falling.

Syndrome Nursing Diagnosis

A syndrome nursing diagnosis statement is a cluster of nursing diagnoses that occur together and are best addressed together and through similar interventions. To create a syndrome diagnosis, two or more nursing diagnoses must be used as defining characteristics (S) that create a syndrome. Related factors may be used if they add clarity to the definition but are not required.[26]

A syndrome statement consists of these items:

Problem (P): The syndrome

Signs and Symptoms (S): The defining characteristics are two or more similar nursing diagnoses

Example of a Syndrome Nursing Diagnosis

Refer to Scenario C in the “Assessment” section of this chapter. Clustering the data for Ms. J. identifies several similar NANDA-I nursing diagnoses of Decreased Activity Tolerance and Social Isolation nursing diagnoses that can be categorized under a syndrome diagnosis called Frail Elderly Syndrome. This syndrome is defined as a “dynamic state of unstable equilibrium that affects the older individual experiencing deterioration in one or more domains of health (physical, functional, psychological, or social) and leads to increased susceptibility to adverse health effects, in particular disability.”[27]

Example

The components of a syndrome nursing diagnosis for Ms. J. would be:

Problem (P): Risk for Frail Elderly Syndrome

Signs and Symptoms (S): The nursing diagnoses of Activity Intolerance and Social Isolation

Additional related factor: Fear of falling

A correctly written syndrome diagnosis statement for Ms. J. would be written as follows:

Risk for Frail Elderly Syndrome related to activity intolerance, social isolation, and fear of falling

See Table 4.4a for a summary of the types of nursing diagnoses.

Table 4.4a. Types of Nursing Diagnoses

| Diagnosis | What Is It? | Example of Nursing Diagnosis Statement |

|---|---|---|

| Problem-Focused (Actual) | Problem is present at the time of assessment | (PES) Fluid Volume Excess R/T excessive fluid intake AEB bilateral basilar crackles in the lungs, bilateral 2+ pitting edema in the ankles and feet, an increased weight of 10 pounds over 1 week, and the client reports, “My ankles feel swollen.” |

| Health-Promotion | A motivation/desire to increase well-being or a client’s strength | Enhanced Readiness for Health Promotion AEB expressed desire to “learn more about health so I can take better care of myself.” |

| Risk | Problem is likely to develop | Risk for Falls AEB dizziness and decreased lower extremity strength |

| Syndrome | Cluster of nursing diagnoses that occur together and are best addressed together | Risk for Frail Elderly Syndrome R/T activity intolerance, social isolation, and fear of falling |

![]() It can feel overwhelming for nursing students to determine which nursing diagnoses to use for their clients due to the complexity of nursing diagnoses. Rest assured, use of nursing diagnoses becomes easier with practice and exposure to client care plans. Refer to trustworthy sources, such as a nursing diagnosis handbook or reputable care-planning resources to become aware of current NANDA-I nursing diagnoses.

It can feel overwhelming for nursing students to determine which nursing diagnoses to use for their clients due to the complexity of nursing diagnoses. Rest assured, use of nursing diagnoses becomes easier with practice and exposure to client care plans. Refer to trustworthy sources, such as a nursing diagnosis handbook or reputable care-planning resources to become aware of current NANDA-I nursing diagnoses.

Nursing diagnoses can be viewed to establish familiarity with them on the Nanda Diagnoses website, but be aware this is not an official NANDA nursing diagnosis site. Evidence-based care planning resources should be used when planning client care.

Prioritization

After identifying nursing diagnoses, the next step is prioritizing diagnoses and actions according to the specific needs of the client. Nurses prioritize their actions while providing client care multiple times every day. Prioritization is the skillful process of deciding which actions to complete first for client safety and optimal client outcomes. Through prioritization, the most significant nursing problems, as well as the most important interventions in the nursing care plan, are identified.

Client care situations fall somewhere between routine care and a medical crisis. It is essential that life-threatening concerns and crises are identified immediately and addressed quickly. Depending on the severity of a problem, the steps of the nursing process may be performed in a matter of seconds for life-threatening concerns, such as respiratory arrest or cardiac arrest. Critical situations can occur at any time when providing nursing care for clients, and the steps of the nursing process must be performed rapidly. Nursing students must have a full understanding of how to correctly analyze cues, cluster data, form appropriate hypotheses, and prioritize hypotheses to take appropriate action using clinical judgment. Nurses recognize cues signaling a change in client condition, apply evidence-based practices in a crisis, and communicate effectively with interprofessional team members.

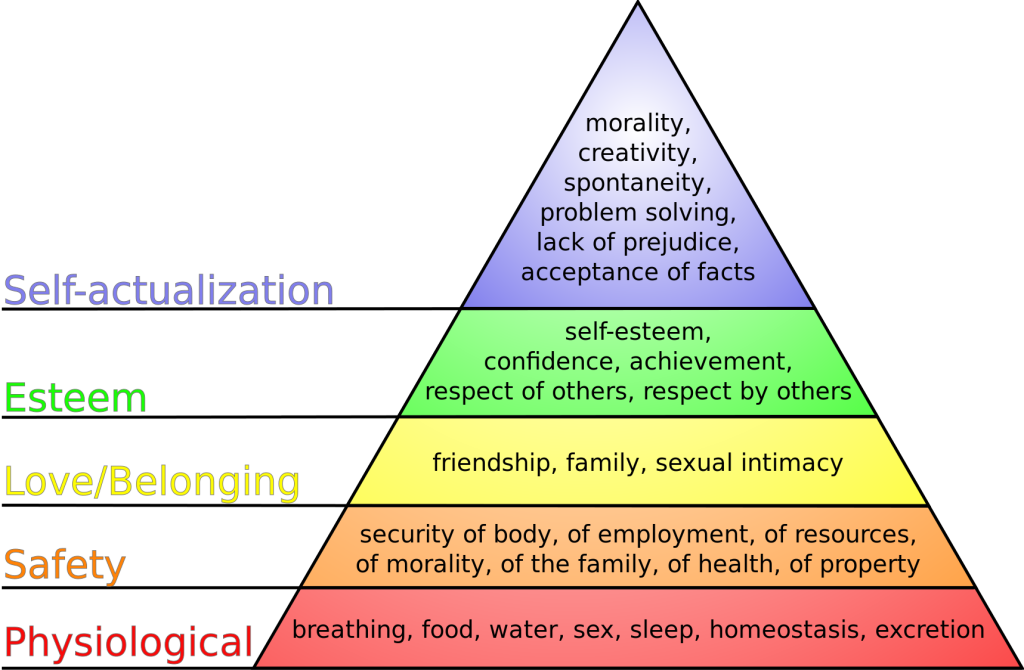

There are several concepts used to prioritize, including Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, the “ABCs” (Airway, Breathing and Circulation), and acute, uncompensated conditions. See the infographic in Figure 4.7b[28] on The How To of Prioritization.

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs is used to categorize the most urgent client needs. The bottom levels of the pyramid represent the top priority needs of physiological needs intertwined with safety. See Figure 4.8[29] for an image of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. You may be asking yourself, “What about the ABCs – isn’t airway the most important?” The answer to that question is “it depends on the situation and the associated safety considerations.” Consider this scenario – you are driving home after a lovely picnic in the country and come across a fiery car crash. As you approach the car, you see that the passenger is not breathing. Using Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs to prioritize your actions, you remove the passenger from the car first due to safety even though he is not breathing. After ensuring safety and calling for help, you follow the steps to perform cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) to establish circulation, airway, and breathing until help arrives.

In addition to using Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs and the ABCs of airway, breathing, and circulation, the nurse also considers if the client’s condition is an acute or chronic problem. Acute, uncompensated conditions require priority interventions over chronic conditions. Additionally, actual problems generally receive priority over potential problems, but risk problems sometimes receive priority depending on the client vulnerability and risk factors.

Example of Prioritization

Refer to Scenario C in the “Assessment” section of this chapter. Four types of nursing diagnoses were identified for Ms. J.: Excess Fluid Volume, Enhanced Readiness for Health Promotion, Risk for Falls, and Risk for Frail Elderly Syndrome. The top priority diagnosis is Excess Fluid Volume because this condition affects the physiological needs of breathing, homeostasis, and excretion. However, the Risk for Falls diagnosis comes in a close second because of safety implications and potential injury that could occur if the client fell.

Media Attributions

- Diagnosis in the Nursing Process Compared to the NCJMM

- ORN-Icons-stethoscope-300×300

- Prioritization infograph picture

- Maslow’s_hierarchy_of_needs.svg

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association. ↵

- “Diagnosis in the Nursing Process Compared to the NCJMM” by Tami Davis is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Herdman, T. H., Kamitsuru, S., & Lopes, C. T. (Eds.). (2021). Nursing diagnoses: Definitions and classification 2021-2023, Twelfth Edition. Thieme Publishers New York. ↵

- Herdman, T. H., Kamitsuru, S., & Lopes, C. T. (Eds.). (2021). Nursing diagnoses: Definitions and classification 2021-2023, Twelfth Edition. Thieme Publishers New York. ↵

- Gordon, M. (2008). Assess notes: Nursing assessment and diagnostic reasoning. F.A. Davis Company. ↵

- Gordon, M. (2008). Assess notes: Nursing assessment and diagnostic reasoning. F.A. Davis Company. ↵

- Herdman, T. H., Kamitsuru, S., & Lopes, C. T. (Eds.). (2021). Nursing diagnoses: Definitions and classification 2021-2023, Twelfth Edition. Thieme Publishers New York. ↵

- Herdman, T. H., Kamitsuru, S., & Lopes, C. T. (Eds.). (2021). Nursing diagnoses: Definitions and classification 2021-2023, Twelfth Edition. Thieme Publishers New York. ↵

- Herdman, T. H., Kamitsuru, S., & Lopes, C. T. (Eds.). (2021). Nursing diagnoses: Definitions and classification 2021-2023, Twelfth Edition. Thieme Publishers New York. ↵

- Herdman, T. H., Kamitsuru, S., & Lopes, C. T. (Eds.). (2021). Nursing diagnoses: Definitions and classification 2021-2023, Twelfth Edition. Thieme Publishers New York. ↵

- Herdman, T. H., Kamitsuru, S., & Lopes, C. T. (Eds.). (2021). Nursing diagnoses: Definitions and classification 2021-2023, Twelfth Edition. Thieme Publishers New York. ↵

- Herdman, T. H., Kamitsuru, S., & Lopes, C. T. (Eds.). (2021). Nursing diagnoses: Definitions and classification 2021-2023, Twelfth Edition. Thieme Publishers New York. ↵

- Herdman, T. H., Kamitsuru, S., & Lopes, C. T. (Eds.). (2021). Nursing diagnoses: Definitions and classification 2021-2023, Twelfth Edition. Thieme Publishers New York. ↵

- Herdman, T. H., Kamitsuru, S., & Lopes, C. T. (Eds.). (2021). Nursing diagnoses: Definitions and classification 2021-2023, Twelfth Edition. Thieme Publishers New York. ↵

- Herdman, T. H., Kamitsuru, S., & Lopes, C. T. (Eds.). (2021). Nursing diagnoses: Definitions and classification 2021-2023, Twelfth Edition. Thieme Publishers New York. ↵

- Herdman, T. H., Kamitsuru, S., & Lopes, C. T. (Eds.). (2021). Nursing diagnoses: Definitions and classification 2021-2023, Twelfth Edition. Thieme Publishers New York. ↵

- Herdman, T. H., Kamitsuru, S., & Lopes, C. T. (Eds.). (2021). Nursing diagnoses: Definitions and classification 2021-2023, Twelfth Edition. Thieme Publishers New York. ↵

- Herdman, T. H., Kamitsuru, S., & Lopes, C. T. (Eds.). (2021). Nursing diagnoses: Definitions and classification 2021-2023, Twelfth Edition. Thieme Publishers New York. ↵

- Herdman, T. H., Kamitsuru, S., & Lopes, C. T. (Eds.). (2021). Nursing diagnoses: Definitions and classification 2021-2023, Twelfth Edition. Thieme Publishers New York. ↵

- Herdman, T. H., Kamitsuru, S., & Lopes, C. T. (Eds.). (2021). Nursing diagnoses: Definitions and classification 2021-2023, Twelfth Edition. Thieme Publishers New York. ↵

- Herdman, T. H., Kamitsuru, S., & Lopes, C. T. (Eds.). (2021). Nursing diagnoses: Definitions and classification 2021-2023, Twelfth Edition. Thieme Publishers New York. ↵

- NANDA International. (n.d.). Glossary of terms. https://nanda.org/nanda-i-resources/glossary-of-terms/ ↵

- Herdman, T. H., Kamitsuru, S., & Lopes, C. T. (Eds.). (2021). Nursing diagnoses: Definitions and classification 2021-2023, Twelfth Edition. Thieme Publishers New York. ↵

- Herdman, T. H., Kamitsuru, S., & Lopes, C. T. (Eds.). (2021). Nursing diagnoses: Definitions and classification 2021-2023, Twelfth Edition. Thieme Publishers New York. ↵

- Herdman, T. H., Kamitsuru, S., & Lopes, C. T. (Eds.). (2021). Nursing diagnoses: Definitions and classification 2021-2023, Twelfth Edition. Thieme Publishers New York. ↵

- NANDA International. (n.d.). Glossary of terms. https://nanda.org/nanda-i-resources/glossary-of-terms/ ↵

- Herdman, T. H., Kamitsuru, S., & Lopes, C. T. (Eds.). (2021). Nursing diagnoses: Definitions and classification 2021-2023, Twelfth Edition. Thieme Publishers New York. ↵

- “The How To of Prioritization” by Valerie Palarski for Chippewa Valley Technical College is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “Maslow's hierarchy of needs.svg” by J. Finkelstein is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

Organizing data into similar domains or patterns.

An evidence-based assessment framework for identifying patient problems and risks during the assessment phase of the nursing process.

Defined as a “clinical judgment concerning a human response to health conditions/life processes, or a vulnerability for that response, by an individual, family, group or community.

Groups of people who share a characteristic that causes each member to be susceptible to a particular human response, such as demographics, health/family history, stages of growth/development, or exposure to certain events/experiences.

Medical diagnoses, injuries, procedures, medical devices, or pharmacological agents. These conditions are not independently modifiable by the nurse, but support accuracy in nursing diagnosis.

A “clinical judgment concerning an undesirable human response to health condition/life processes that exist in an individual, family, group, or community.

The underlying cause (etiology) of a nursing diagnosis

Observable cues/inferences that cluster as manifestations of a problem-focused, health-promotion diagnosis or syndrome. This does not only imply those things that the nurse can see, but also things that are seen, heard (e.g., the patient/family tells us), touched, or smelled.

A clinical judgment concerning the vulnerability of an individual, family, group, or community for developing an undesirable human response to health conditions/life processes.

Creating nursing diagnosis statements utilizing a problem, etiology, and sign and symptoms format.

The skillful process of deciding which actions to complete first for client safety and optimal client outcomes

A theory used to prioritize the most urgent client needs to address first. The bottom levels of the pyramid represent the most important physiological needs intertwined with safety.