4.2 Aseptic Technique Basic Concepts

Ernstmeyer & Christman - Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

Standard Versus Transmission-Based Precautions

Standard Precautions

Standard precautions are used when caring for all patients to prevent health care associated infections. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), standard precautions are “the minimum infection prevention practices that apply to all patient care, regardless of suspected or confirmed infection status of the patient, in any setting where health care is delivered.”[1] They are based on the principle that all blood, body fluids (except sweat), nonintact skin, and mucous membranes may contain transmissible infectious agents. These standards reduce the risk of exposure for the health care worker and protect the patient from potential transmission of infectious organisms.

Current standard precautions according to the CDC (2019) include the following:

- Appropriate hand hygiene

- Use of personal protective equipment (e.g., gloves, gowns, masks, eyewear) whenever infectious material exposure may occur

- Appropriate patient placement and care using transmission-based precautions when indicated

- Respiratory hygiene/cough etiquette

- Proper handling and cleaning of environment, equipment, and devices

- Safe handling of laundry

- Sharps safety (i.e., engineering and work practice controls)

- Aseptic technique for invasive nursing procedures such as parenteral medication administration[2]

Each of these standard precautions is described in more detail in the following subsections.

Transmission-Based Precautions

In addition to standard precautions, transmission-based precautions are used for patients with documented or suspected infection, or colonization, of highly transmissible or epidemiologically important pathogens. Epidemiologically important pathogens include, but are not limited to, Coronavirus disease (COVID-19), Clostridium difficile (C-diff), Methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), Vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE), Respiratory syncytial sirus (RSV), measles, and tuberculosis (TB). For patients with these types of pathogens, standard precautions are used along with specific transmission-based precautions.

There are four categories of transmission-based precautions: contact precautions, enhanced barrier precautions, droplet precautions, and airborne precautions. Transmission-based precautions are used when the route(s) of transmission is (are) not completely interrupted using standard precautions alone. Some diseases, such as tuberculosis, have multiple routes of transmission so more than one transmission-based precautions category must be implemented. See Table 4.2 outlining the categories of transmission precautions with associated PPE and other precautions. When possible, patients with transmission-based precautions should be placed in a single occupancy room with dedicated patient care equipment (e.g., blood pressure cuffs, stethoscope, thermometer). Transport of the patient and unnecessary movement outside the patient room should be limited. However, when transmission-based precautions are implemented, it is also important for the nurse to make efforts to counteract possible adverse effects of these precautions on patients, such as anxiety, depression, perceptions of stigma, and reduced contact with clinical staff.

Table 4.2 Transmission-Based Precautions[3]

| Precaution | Implementation | PPE and Other Precautions |

|---|---|---|

| Contact | Known or suspected infections with increased risk for contact transmission (e.g., draining wounds, fecal incontinence) or with epidemiologically important organisms, such as C-diff, MRSA, VRE, or RSV |

Note: Use only soap and water for hand hygiene in patients with C. difficile infection. |

| Enhanced barrier | Used during high-contact resident care activities for individuals colonized or infected with a multidrug-resistant organism (MDRO), as well as those at increased risk of MDRO acquisition |

|

| Droplet | Known or suspected infection with pathogens transmitted by large respiratory droplets generated by coughing, sneezing, or talking, such as influenza, coronavirus, or pertussis |

|

| Airborne | Known or suspected infection with pathogens transmitted by small respiratory droplets, such as measles, tuberculosis, and disseminated herpes zoster | Fit-tested N-95 respirator or PAPR

|

View a list of transmission-based precautions used for specific medical conditions at the CDC Guideline for Isolation Precautions.

Patient Transport

Several principles are used to guide transport of patients requiring transmission-based precautions. In the inpatient and residential settings, these principles include the following:

- Limiting transport for essential purposes only, such as diagnostic and therapeutic procedures that cannot be performed in the patient’s room

- Using appropriate barriers on the patient consistent with the route and risk of transmission (e.g., mask, gown, covering the affected areas when infectious skin lesions or drainage is present)

- Notify other health care personnel involved in the care of the patient of the transmission-based precautions. For example, when transporting the patient to radiology, inform the radiology technician of the precautions.[4]

Appropriate Hand Hygiene

Hand hygiene is the single most important practice to reduce the transmission of infectious agents in health care settings and is an essential element of standard precautions.[5] Routine handwashing during appropriate moments is a simple and effective way to prevent infection. However, it is estimated that health care professionals, on average, properly clean their hands less than 50% of the time it is indicated.[6] The Joint Commission, the organization that sets evidence-based standards of care for hospitals, recently updated its hand hygiene standards in 2018 to promote enforcement. If a Joint Commission surveyor witnesses an individual failing to properly clean their hands when it is indicated, a deficiency will be cited requiring improvement by the agency. This deficiency could potentially jeopardize a hospital’s accreditation status and their ability to receive payment for patient services. Therefore, it is essential for all health care workers to ensure they are using proper hand hygiene at the appropriate times.[7]

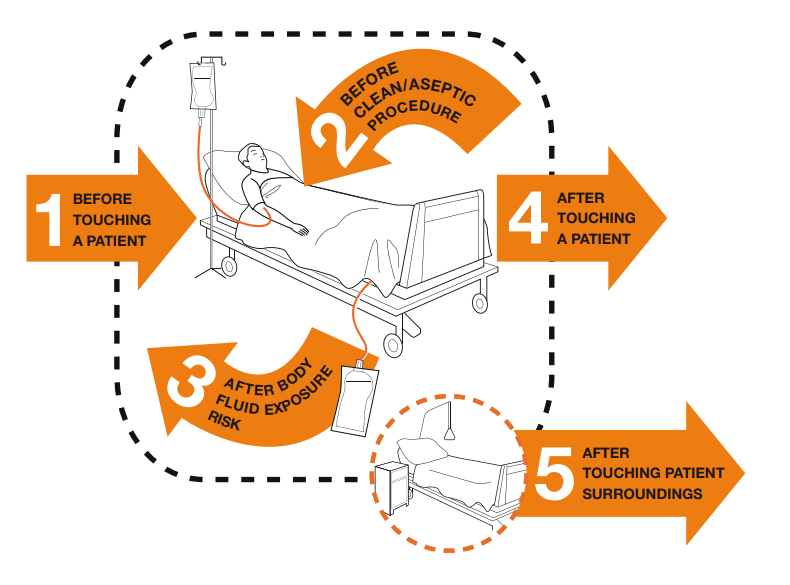

There are several evidence-based guidelines for performing appropriate hand hygiene. These guidelines include frequency of performing hand hygiene according to the care circumstances, solutions used, and technique performed. The Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC) recommends health care personnel perform hand hygiene at specific times when providing care to patients. These moments are often referred to as the “Moments for Hand Hygiene.”[8] See Figures 4.1[9] and 4.2[10] for an illustration and application of the five moments of hand hygiene. The five moments of hand hygiene are as follows:

- Immediately before touching a patient

- Before performing an aseptic task or handling invasive devices

- Before moving from a soiled body site to a clean body site on a patient

- After touching a patient or their immediate environment

- After contact with blood, body fluids, or contaminated surfaces (with or without glove use)

When performing hand hygiene, washing with soap and water, or an approved alcohol-based hand rub solution that contains at least 60% alcohol, may be used. Unless hands are visibly soiled, an alcohol-based hand rub is preferred over soap and water in most clinical situations due to evidence of improved compliance. Handrubs are also preferred because they are generally less irritating to health care worker’s hands. However, it is important to recognize that alcohol-based rubs do not eliminate some types of germs, such as Clostridium difficile (C-diff).

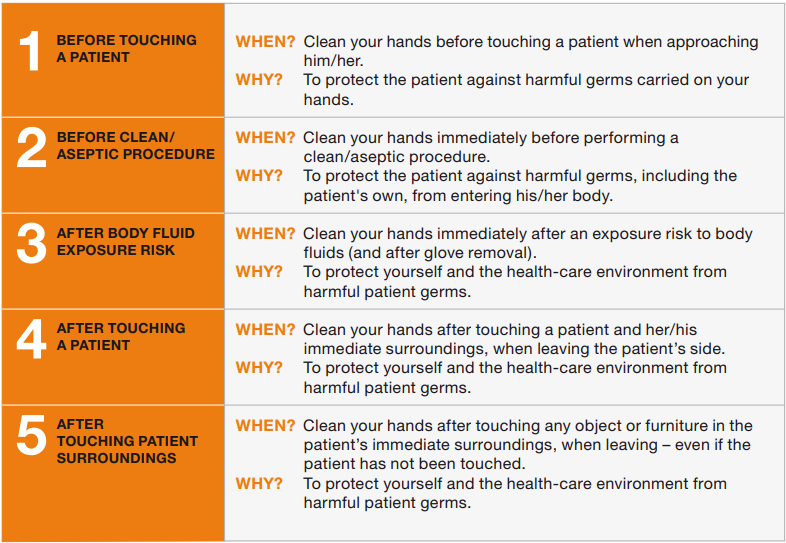

When using the alcohol-based handrub method, the CDC recommends the following steps. See Figure 4.3[11] for a handrub poster created by the World Health Organization.

- Apply product to the palm of one hand in an amount that will cover all surfaces.

- Rub hands together, covering all the surfaces of the hands, fingers, and wrists until the hands are dry. Surfaces include the palms and fingers, between the fingers, the backs of the hands and fingers, the fingertips, and the thumbs.

- The process should take about 20 seconds, and the solution should be dry.[12]

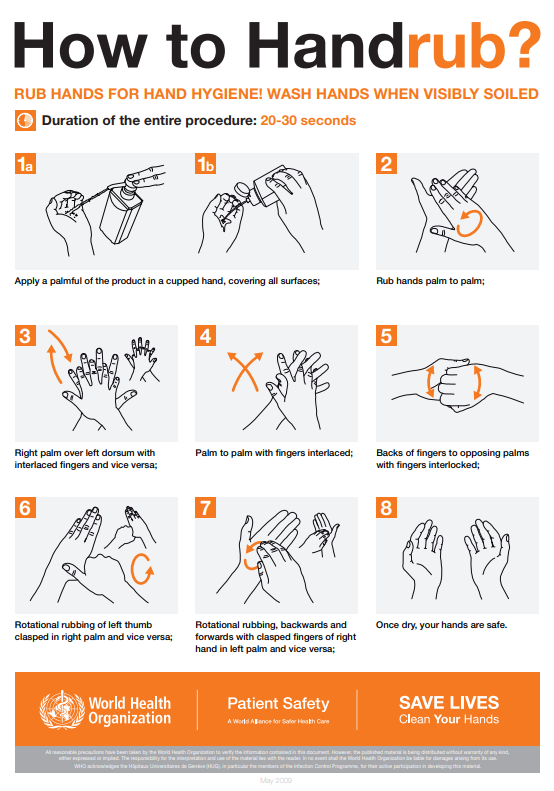

When washing with soap and water, the CDC recommends using the following steps. See Figure 4.4[13] for an image of a handwashing poster created by the World Health Organization.

- Wet hands with warm or cold running water and apply facility-approved soap.

- Lather hands by rubbing them together with the soap. Use the same technique as the handrub process to clean the palms and fingers, between the fingers, the backs of the hands and fingers, the fingertips, and the thumbs.

- Scrub thoroughly for at least 20 seconds.

- Rinse hands well under clean, running water.

- Dry the hands using a clean towel or disposable toweling.

- Use a clean paper towel to shut off the faucet.[14]

By performing hand hygiene at the proper moments and using appropriate techniques, you will ensure your hands are safe and you are not transmitting infectious organisms to yourself or others.

Hand Hygiene for Healthcare Workers on YouTube[15]

Personal Protective Equipment (PPE)

Personal protective equipment (PPE) includes gloves, gowns, face shields, goggles, and masks used to prevent the spread of infection to and from patients and health care providers. Depending on the anticipated exposure, PPE may include the use of gloves, a fluid-resistant gown, goggles or a face shield, and a mask or respirator. When used for a patient with transmission-based precautions, PPE supplies are typically stored in an isolation cart next to the patient’s room, and a card is posted on the door alerting staff and visitors to precautions needed before entering the room.

Gloves

Gloves protect both patients and health care personnel from exposure to infectious material that may be carried on the hands. Gloves are used to prevent contamination of health care personnel hands during activities such as the following:

- Anticipating direct contact with blood or body fluids, mucous membranes, nonintact skin, and other potentially infectious material

- Having direct contact with patients who are colonized or infected with pathogens transmitted by the contact route, such as Vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE), Methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), and Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV)

- Handling or touching visibly or potentially contaminated patient care equipment and environmental surfaces[16]

Nonsterile disposable medical gloves for routine patient care are made of a variety of materials, such as latex, vinyl, and nitrile. Many people are allergic to latex, so be sure to check for latex allergies for the patient and other health care professionals. See Figure 4.5[17] for an image of nonsterile medical gloves in various sizes in a health care setting. At times, gloves may need to be changed when providing care to a single patient to prevent cross-contamination of body sites. It is also necessary to change gloves if the patient interaction requires touching portable computer keyboards or other mobile equipment that is transported from room to room. Discarding gloves between patients is necessary to prevent transmission of infectious material. Gloves must not be washed for subsequent reuse because microorganisms cannot be reliably removed from glove surfaces, and continued glove integrity cannot be ensured.[18]

When gloves are worn in combination with other PPE, they are put on last. Gloves that fit snugly around the wrist should be used in combination with isolation gowns because they will cover the gown cuff and provide a more reliable continuous barrier for the arms, wrists, and hands.

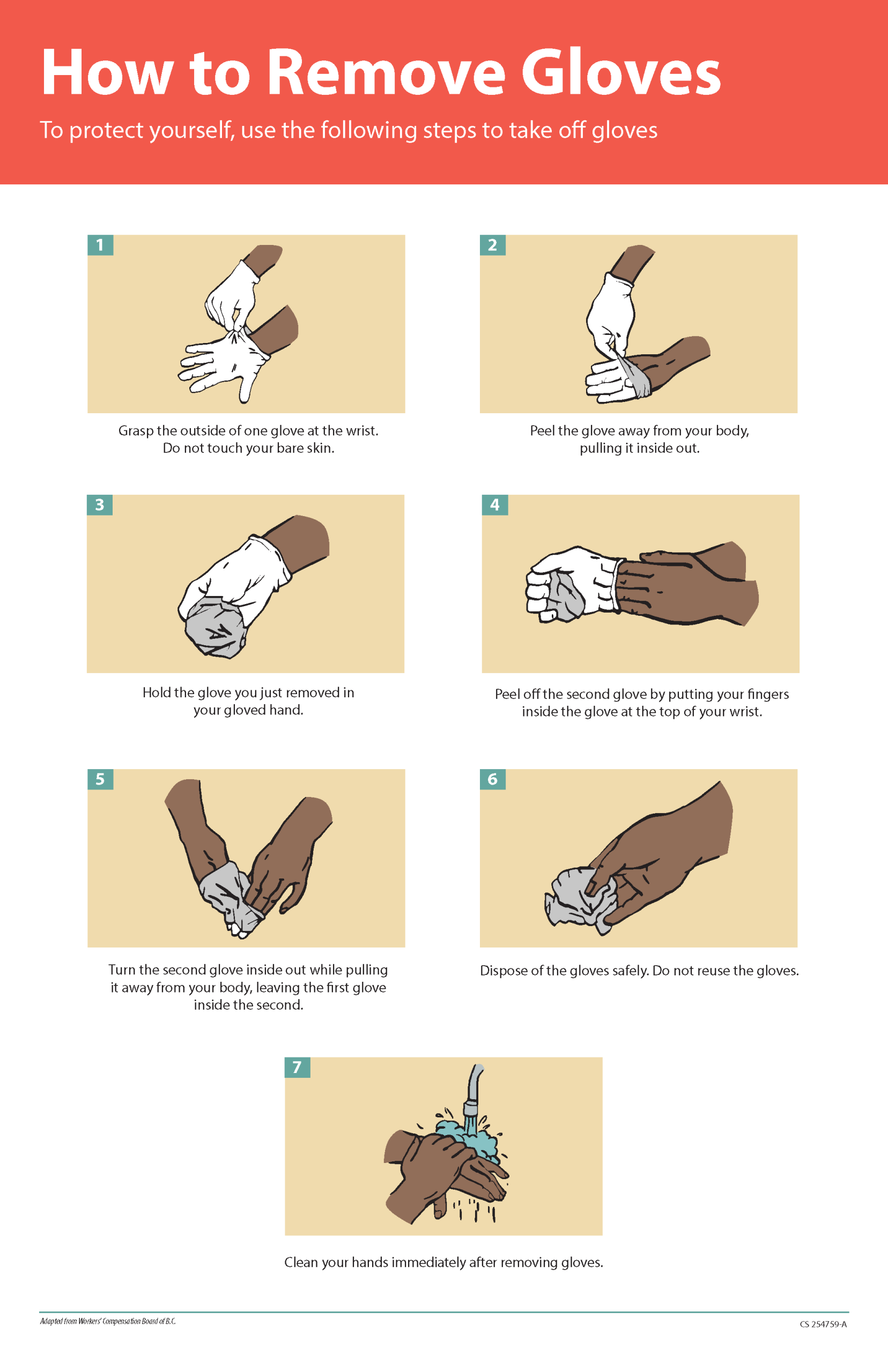

Gloves should be removed properly to prevent contamination. See Figure 4.6[19] for an illustration of properly removing gloves. Hand hygiene should be performed following glove removal to ensure the hands will not carry potentially infectious material that might have penetrated through unrecognized tears or contaminated the hands during glove removal. One method for properly removing gloves includes the following steps:

- Grasp the outside of one glove near the wrist. Do not touch your skin.

- Peel the glove away from your body, pulling it inside out.

- Hold the removed glove in your gloved hand.

- Put your fingers inside the glove at the top of your wrist and peel off the second glove.

- Turn the second glove inside out while pulling it away from your body, leaving the first glove inside the second.

- Dispose of the gloves safely. Do not reuse.

- Perform hand hygiene immediately after removing the gloves.[20]

Gowns

Isolation gowns are used to protect the health care worker’s arms and exposed body areas and to prevent contamination of their clothing with blood, body fluids, and other potentially infectious material. Isolation gowns may be disposable or washable/reusable. See Figure 4.7[21] for an image of a nurse wearing an isolation gown along with goggles and a respirator. When using standard precautions, an isolation gown is worn only if contact with blood or body fluid is anticipated. However, when contact transmission-based precautions are in place, donning of both gown and gloves upon room entry is indicated to prevent unintentional contact of clothing with contaminated environmental surfaces.

Gowns are usually the first piece of PPE to be donned. Isolation gowns should be removed before leaving the patient room to prevent possible contamination of the environment outside the patient’s room. Isolation gowns should be removed in a manner that prevents contamination of clothing or skin. The outer, “contaminated,” side of the gown is turned inward and rolled into a bundle, and then it is discarded into a designated container to contain contamination. See more information about putting on and removing PPE in the subsection below.[22]

Masks

The mucous membranes of the mouth, nose, and eyes are susceptible portals of entry for infectious agents. Masks are used to protect these sites from entry of large infectious droplets. See Figure 4.8[23] for an image of nurse wearing a surgical mask. Masks have three primary purposes in health care settings:

- Used by health care personnel to protect them from contact with infectious material from patients (e.g., respiratory secretions and sprays of blood or body fluids), consistent with standard precautions and droplet transmission precautions

- Used by health care personnel when engaged in procedures requiring sterile technique to protect patients from exposure to infectious agents potentially carried in a health care worker’s mouth or nose

- Placed on coughing patients to limit potential dissemination of infectious respiratory secretions from the patient to others in public areas (i.e., respiratory hygiene)[24]

Masks may be used in combination with goggles or a face shield to provide more complete protection for the face. Masks should not be confused with respirators used during airborne transmission-based precautions to prevent inhalation of small, aerosolized infectious droplets.[25]

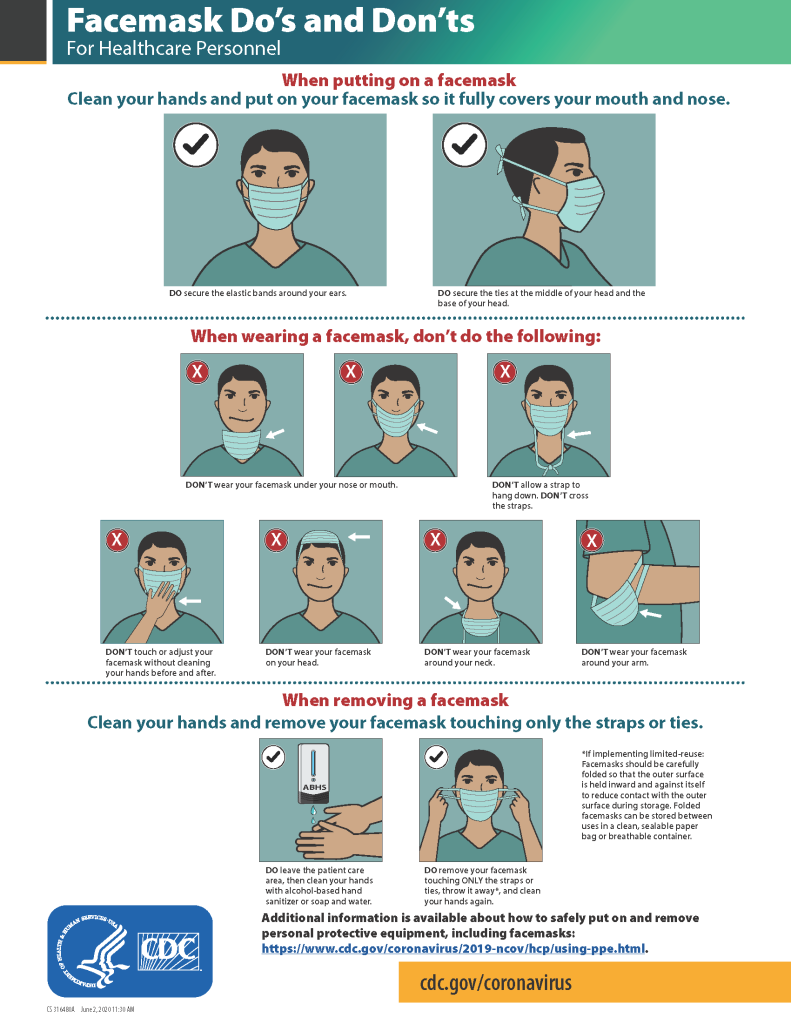

It is important to properly wear and remove masks to avoid contamination. See Figure 4.9[26] for CDC face mask recommendations for health care personnel.

Goggles/Face Shields

Eye protection chosen for specific work situations (e.g., goggles or face shields) depends upon the circumstances of exposure, other PPE used, and personal vision needs. Personal eyeglasses are not considered adequate eye protection. See Figure 4.10[27] for an image of a health care professional wearing a face shield along with a N95 respirator.

Respirators and PAPRs

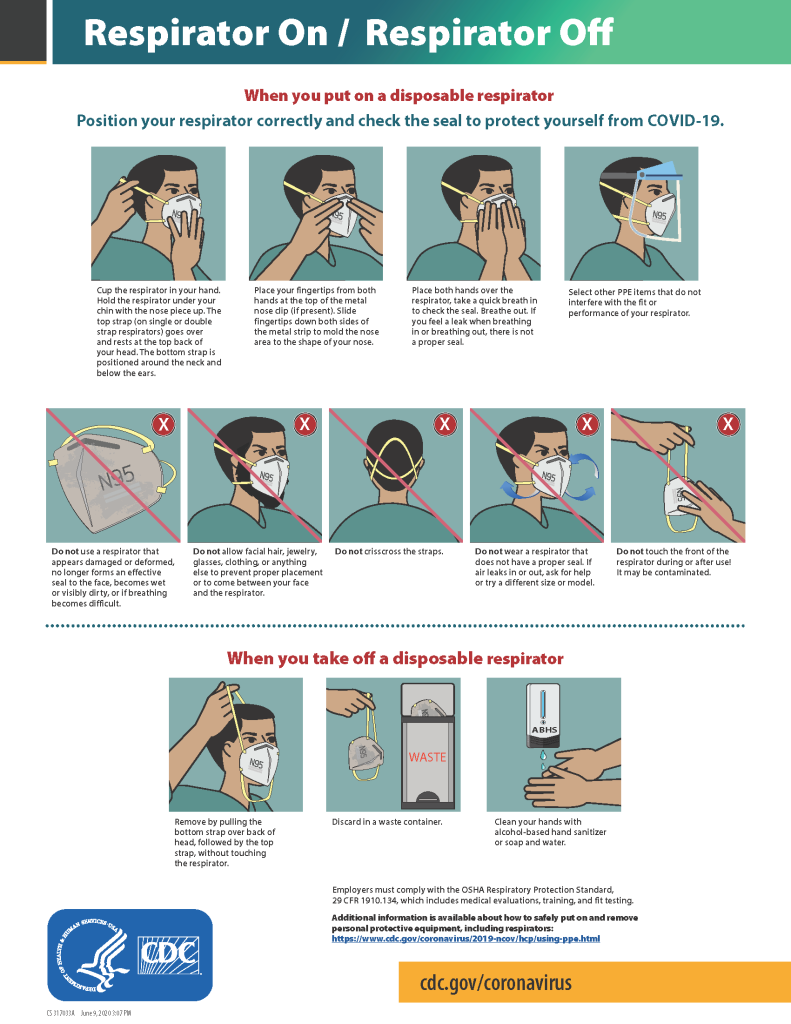

Respiratory protection used during airborne transmission precautions requires the use of special equipment. Traditionally, a fitted respirator mask with N95 or higher filtration has been worn by health care professionals to prevent inhalation of small airborne infectious particles. A user-seal check (formerly called a “fit check”) should be performed by the wearer of a respirator each time a respirator is donned to minimize air leakage around the facepiece.

A newer piece of equipment used for respiratory protection is the powered air-purifying respirator (PAPR). A PAPR is an air-purifying respirator that uses a blower to force air through filter cartridges or canisters into the breathing zone of the wearer. This process creates an air flow inside either a tight-fitting facepiece or loose-fitting hood or helmet, providing a higher level of protection against aerosolized pathogens, such as COVID-19, than a N95 respirator. See Figure 4.11[28] for an example of PAPR in use.

The CDC currently recommends N95 or higher level respirators for personnel exposed to patients with suspected or confirmed tuberculosis and other airborne diseases, especially during aerosol-generating procedures such as respiratory-tract suctioning.[29] It is important to apply, wear, and remove respirators appropriately to avoid contamination. See Figure 4.12[30] for CDC recommendations when wearing disposable respirators.

How to Put On (Don) PPE Gear

Follow agency policy for donning PPE according to transmission-based precautions. More than one donning method for putting on PPE may be acceptable. The CDC recommends the following steps for donning PPE[31]:

- Identify and gather the proper PPE to don. Ensure the gown size is correct.

- Perform hand hygiene using hand sanitizer or wash hands with soap and water.

- Put on the isolation gown. Tie all of the ties on the gown. Assistance may be needed by other health care personnel to tie back ties.

- Based on specific transmission-based precautions and agency policy, put on a mask or N95 respirator. The top strap should be placed on the crown (top) of the head, and the bottom strap should be at the base of the neck. If the mask has loops, hook them appropriately around your ears. Masks and respirators should extend under the chin, and both your mouth and nose should be protected. Perform a user-seal check each time you put on a respirator. If the respirator has a nosepiece, it should be fitted to the nose with both hands, but it should not be bent or tented. Masks typically require the nosepiece to be pinched to fit around the nose, but do not pinch the nosepiece of a respirator with one hand. Do not wear a respirator or mask under your chin or store it in the pocket of your scrubs between patients.

- Put on a face shield or goggles when indicated. When wearing an N95 respirator with eye protection, select eye protection that does not affect the fit or seal of the respirator and one that does not affect the position of the respirator. Goggles provide excellent protection for the eyes, but fogging is common. Face shields provide full-face coverage.

- Put on gloves. Gloves should cover the cuff (wrist) of the gown.

- You may now enter the patient’s room.

How to Take Off (Doff) PPE Gear

More than one doffing method for removing PPE may be acceptable. Train using your agency’s procedure, and practice until you have successfully mastered the steps to avoid contamination of yourself and others. There are established cases of nurses dying from disease transmitted during incorrect removal of PPE. Below are sample steps of doffing established by the CDC[34]:

- Remove the gloves. Ensure glove removal does not cause additional contamination of the hands. Gloves can be removed using more than one technique (e.g., glove-in-glove or bird beak).

- Remove the gown. Untie all ties (or unsnap all buttons). Some gown ties can be broken rather than untied; do so in a gentle manner and avoid a forceful movement. Reach up to the front of your shoulders and carefully pull the gown down and away from your body. Rolling the gown down is also an acceptable approach. Dispose of the gown in a trash receptacle. If it is a washable gown, place it in the specified laundry bin for PPE in the room.

- Health care personnel may now exit the patient room.

- Perform hand hygiene.

- Remove the face shield or goggles. Carefully remove the face shield or goggles by grabbing the strap and pulling upwards and away from head. Do not touch the front of the face shield or goggles.

- Remove and discard the respirator or face mask. Do not touch the front of the respirator or face mask. Remove the bottom strap by touching only the strap and bringing it carefully over the head. Grasp the top strap and bring it carefully over the head, and then pull the respirator away from the face without touching the front of the respirator. For masks, carefully untie (or unhook ties from the ears) and pull the mask away from your face without touching the front.

- Perform hand hygiene after removing the respirator/mask. If your workplace is practicing reuse, perform hand hygiene before putting it on again.

View a YouTube Video from the CDC on Putting on PPE[35]

View a YouTube Video from the CDC on Removing PPE[36]

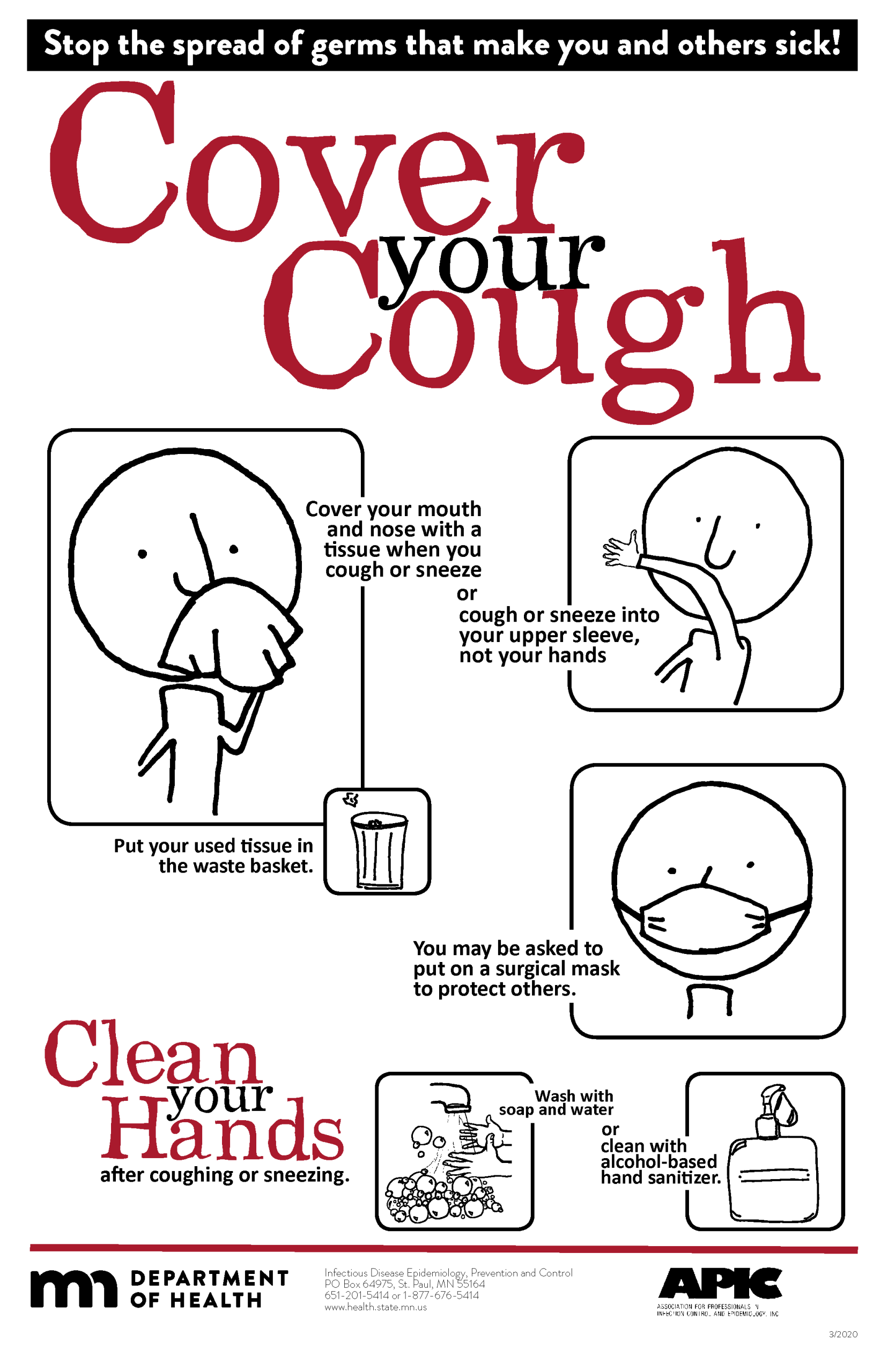

Respiratory Hygiene

Respiratory hygiene is targeted at patients, accompanying family members and friends, and health care workers with undiagnosed transmissible respiratory infections. It applies to any person with signs of illness, including cough, congestion, rhinorrhea, or increased production of respiratory secretions when entering a health care facility. See Figure 4.13[37] for an example of a “Cover Your Cough” poster used in public areas to promote respiratory hygiene. The elements of respiratory hygiene include the following:

- Education of health care facility staff, patients, and visitors

- Posted signs, in language(s) appropriate to the population served, with instructions to patients and accompanying family members or friends

- Source control measures for a coughing person (e.g., covering the mouth/nose with a tissue when coughing and prompt disposal of used tissues, or applying surgical masks on the coughing person to contain secretions)

- Hand hygiene after contact with one’s respiratory secretions

- Spatial separation, ideally greater than 3 feet, of persons with respiratory infections in common waiting areas when possible.[38]

Health care personnel are advised to wear a mask and use frequent hand hygiene when examining and caring for patients with signs and symptoms of a respiratory infection. Health care personnel who have a respiratory infection are advised to avoid direct patient contact, especially with high-risk patients. If this is not possible, then a mask should be worn while providing patient care.[39]

Environmental Measures

Routine cleaning and disinfecting surfaces in patient-care areas are part of standard precautions. The cleaning and disinfecting of all patient-care areas are important for frequently touched surfaces, especially those closest to the patient that are most likely to be contaminated (e.g., bedrails, bedside tables, commodes, doorknobs, sinks, surfaces, and equipment in close proximity to the patient).

Medical equipment and instruments/devices must also be cleaned to prevent patient-to-patient transmission of infectious agents. For example, stethoscopes should be cleaned before and after use for all patients. Patients who have transmission-based precautions should have dedicated medical equipment that remains in their room (e.g., stethoscope, blood pressure cuff, thermometer). When dedicated equipment is not possible, such as a unit-wide bedside blood glucose monitor, disinfection after each patient’s use should be performed according to agency policy.[40]

Disposal of Contaminated Waste

Medical waste requires careful disposal according to agency policy. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) has established measures for discarding regulated medical waste items to protect the workers who generate medical waste, as well as those who manage the waste from point of generation to disposal. Contaminated waste is placed in a leak-resistant biohazard bag, securely closed, and placed in a labeled, leakproof, puncture-resistant container in a storage area. Sharps containers are used to dispose of sharp items such as discarded tubes with small amounts of blood, scalpel blades, needles, and syringes.[41]

Sharps Safety

Injuries due to needles and other sharps have been associated with transmission of blood-borne pathogens (BBP), including hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and HIV to health care personnel. The prevention of sharps injuries is an essential element of standard precautions and includes measures to handle needles and other sharp devices in a manner that will prevent injury to the user and to others who may encounter the device during or after a procedure. The Bloodborne Pathogens Standard is a regulation that prescribes safeguards to protect workers against health hazards related to blood-borne pathogens. It includes work practice controls, hepatitis B vaccinations, hazard communication and training, plans for when an employee is exposed to a BBP, and recordkeeping.

When performing procedures that include needles or other sharps, dispose of these items immediately in FDA-cleared sharps disposal containers. Additionally, to prevent needlestick injuries, needles and other contaminated sharps should not be recapped. See Figure 4.14[42] for an image of a sharps disposal container. FDA-cleared sharps disposal containers are made from rigid plastic and come marked with a line that indicates when the container should be considered full, which means it’s time to dispose of the container. When a sharps disposal container is about three-quarters full, follow agency policy for proper disposal of the container.

If you are stuck by a needle or other sharps or are exposed to blood or other potentially infectious materials in your eyes, nose, mouth, or on broken skin, immediately flood the exposed area with water and clean any wound with soap and water. Report the incident immediately to your instructor or employer and seek immediate medical attention according to agency and school policy.

Textiles and Laundry

Soiled textiles, including bedding, towels, and patient or resident clothing may be contaminated with pathogenic microorganisms. However, the risk of disease transmission is negligible if they are handled, transported, and laundered in a safe manner. Follow agency policy for handling soiled laundry using standard precautions. Key principles for handling soiled laundry are as follows:

- Do not shake items or handle them in any way that may aerosolize infectious agents.

- Avoid contact of one’s body and personal clothing with the soiled items being handled.

- Place soiled items in a laundry bag or designated bin in the patient’s room before transporting to a laundry area. When laundry chutes are used, they must be maintained to minimize dispersion of aerosols from contaminated items.[43]

Media Attributions

- 5Moments_Image

- handrub

- how to handrub

- how to handwash

- fs-facemask-dos-donts

- 15650272810_b88259cdbd_k

- PAPRs_in_use_01

- fs-respirator-on-off

- Sharps-Containers

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016, January 26). Standard precautions for all patient care. https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/basics/standard-precautions.html ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016, January 26). Standard precautions for all patient care. https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/basics/standard-precautions.html ↵

- Siegel, J. D., Rhinehart, E., Jackson, M., Chiarello, L., & Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. (2019, July 22). 2007 guideline for isolation precautions: Preventing transmission of infectious agents in healthcare settings. https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/guidelines/isolation/index.html ↵

- Siegel, J. D., Rhinehart, E., Jackson, M., Chiarello, L., & Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. (2019, July 22). 2007 guideline for isolation precautions: Preventing transmission of infectious agents in healthcare settings. https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/guidelines/isolation/index.html ↵

- Siegel, J. D., Rhinehart, E., Jackson, M., Chiarello, L., & Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. (2019, July 22). 2007 guideline for isolation precautions: Preventing transmission of infectious agents in healthcare settings. https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/guidelines/isolation/index.html ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019, April 29). Hand hygiene in healthcare settings. https://www.cdc.gov/handhygiene/ ↵

- The Joint Commission. (n.d.). Update: Citing observations of hand hygiene noncompliance. https://www.jointcommission.org/-/media/tjc/documents/standards/jc-requirements/ambulatory-care/2018/update_citing_observations_of_hand_hygiene_noncompliancepdf.pdf?db=web&hash=F89BFFFAEDA700CC2E667049D8F542B2 ↵

- World Health Organization. (n.d.). My 5 moments of hand hygiene. https://www.who.int/infection-prevention/campaigns/clean-hands/5moments/en/ ↵

- “5Moments_Image.gif” by World Health Organization is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. Access for free at https://www.who.int/infection-prevention/campaigns/clean-hands/5moments/en/ ↵

- This work is derived from “Hand_Hygiene_When_and_How_Leaflet.pdf” by World Health Organization and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. Access for free at https://www.who.int/infection-prevention/tools/hand-hygiene/workplace_reminders/en/ ↵

- This work is derived from “Hand_Hygiene_When_and_How_Leaflet.pdf” by World Health Organization and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. Access for free at https://www.who.int/infection-prevention/tools/hand-hygiene/workplace_reminders/en/ ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019, April 29). Hand hygiene in healthcare settings. https://www.cdc.gov/handhygiene/ ↵

- “How_To_HandWash_Poster.pdf” by World Health Organization is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. Access for free at https://www.who.int/infection-prevention/campaigns/clean-hands/5moments/en/ ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019, April 29). Hand hygiene in healthcare settings. https://www.cdc.gov/handhygiene/ ↵

- RegisteredNurseRN. (2018, December 1). Hand hygiene for healthcare workers | Hand washing soap and water technique nursing skill [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. Video used with permission. https://youtu.be/G5-Rp-6FMCQ ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016, January 26). Standard precautions for all patient care. https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/basics/standard-precautions.html ↵

- “Surgery Centre Accriditation.jpg” by Accredia is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- Siegel, J. D., Rhinehart, E., Jackson, M., Chiarello, L., & Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. (2019, July 22). 2007 guideline for isolation precautions: Preventing transmission of infectious agents in healthcare settings. https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/guidelines/isolation/index.html ↵

- “poster-how-to-remove-gloves.pdf” by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is in the Public Domain. Access for free at https://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/resources/posters.html ↵

- Siegel, J. D., Rhinehart, E., Jackson, M., Chiarello, L., & Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. (2019, July 22). 2007 guideline for isolation precautions: Preventing transmission of infectious agents in healthcare settings. https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/guidelines/isolation/index.html ↵

- “U.S. Navy Doctors, Nurses and Corpsmen Treat COVID Patients in the ICU Aboard USNS Comfort (49825651378).jpg” by Navy Medicine is in the Public Domain. ↵

- Siegel, J. D., Rhinehart, E., Jackson, M., Chiarello, L., & Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. (2019, July 22). 2007 guideline for isolation precautions: Preventing transmission of infectious agents in healthcare settings. https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/guidelines/isolation/index.html ↵

- “USNS Comfort (T-AH 20) Performs Surgery (49803007781).jpg” by Navy Medicine is in the Public Domain. ↵

- Siegel, J. D., Rhinehart, E., Jackson, M., Chiarello, L., & Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. (2019, July 22). 2007 guideline for isolation precautions: Preventing transmission of infectious agents in healthcare settings. https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/guidelines/isolation/index.html ↵

- Siegel, J. D., Rhinehart, E., Jackson, M., Chiarello, L., & Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. (2019, July 22). 2007 guideline for isolation precautions: Preventing transmission of infectious agents in healthcare settings. https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/guidelines/isolation/index.html ↵

- “fs-facemask-dos-donts.pdf” by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is in the Public Domain. Access for free at https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/using-ppe.html ↵

- “Checking Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) in the fight against Ebola” by DFID - UK Department for International Development is licensed under CC BY 2.0 ↵

- “PAPRs_in_use_01.jpg" by Ca.garcia.s is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- Siegel, J. D., Rhinehart, E., Jackson, M., Chiarello, L., & Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. (2019, July 22). 2007 guideline for isolation precautions: Preventing transmission of infectious agents in healthcare settings. https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/guidelines/isolation/index.html ↵

- “fs-respirator-on-off.pdf” by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is in the Public Domain. Access for free at https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/using-ppe.html ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020, August 19). Using personal protective equipment (PPE). https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/using-ppe.html ↵

- RegisteredNurseRN. (2020, May 11). N95 mask - How to wear | N95 respirator nursing skill tutorial [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. Video used with permission. https://youtu.be/i-uD8rUwG48 ↵

- RegisteredNurseRN. (2020, May 29). PPE training video: Donning and doffing PPE nursing skill [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. Video used with permission. https://youtu.be/iwvnA_b9Q8Y ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020, August 19). Using personal protective equipment (PPE). https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/using-ppe.html ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020, July 14). Demonstration of donning (putting on) personal protective equipment (PPE) [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://youtu.be/H4jQUBAlBrI ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020, April 21). Demonstration of doffing (taking off) personal protective equipment (PPE) [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://youtu.be/PQxOc13DxvQ ↵

- “cycphceng.pdf” by https://www.health.state.mn.us/index.html is in the Public Domain. ↵

- Siegel, J. D., Rhinehart, E., Jackson, M., Chiarello, L., & Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. (2019, July 22). 2007 guideline for isolation precautions: Preventing transmission of infectious agents in healthcare settings. https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/guidelines/isolation/index.html ↵

- Siegel, J. D., Rhinehart, E., Jackson, M., Chiarello, L., & Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. (2019, July 22). 2007 guideline for isolation precautions: Preventing transmission of infectious agents in healthcare settings. https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/guidelines/isolation/index.html ↵

- Siegel, J. D., Rhinehart, E., Jackson, M., Chiarello, L., & Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. (2019, July 22). 2007 guideline for isolation precautions: Preventing transmission of infectious agents in healthcare settings. https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/guidelines/isolation/index.html ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2015, November 5). Background I. Regulated medical waste. https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/guidelines/environmental/background/medical-waste.html#i3 ↵

- “Sharps-Containers.jpg” by Federal Drug Administration (FDA) is in the Public Domain. Access for free at https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/safely-using-sharps-needles-and-syringes-home-work-and-travel/sharps-disposal-containers ↵

- Siegel, J. D., Rhinehart, E., Jackson, M., Chiarello, L., & Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. (2019, July 22). 2007 guideline for isolation precautions: Preventing transmission of infectious agents in healthcare settings. https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/guidelines/isolation/index.html ↵

Outcome Identification is the third step of the nursing process (and the third Standard of Practice by the American Nurses Association). This standard is defined as, "The registered nurse identifies expected outcomes for a plan individualized to the health care consumer or the situation." The RN collaborates with the health care consumer, interprofessional team, and others to identify expected outcomes integrating the health care consumer's culture, values, and ethical considerations. Expected outcomes are documented as measurable goals with a time frame for attainment.[1] Outcome identification is performed by RNs and is outside the scope of practice for LPN/VNs, but LPN/VNs must be aware of expected outcomes for clients in their nursing care plan.

An outcome is a measurable behavior demonstrated response to nursing interventions.[2]Outcomes should be identified before nursing interventions are planned. After nursing interventions are implemented, the nurse will evaluate if the outcomes were met in the time frame indicated for that client.

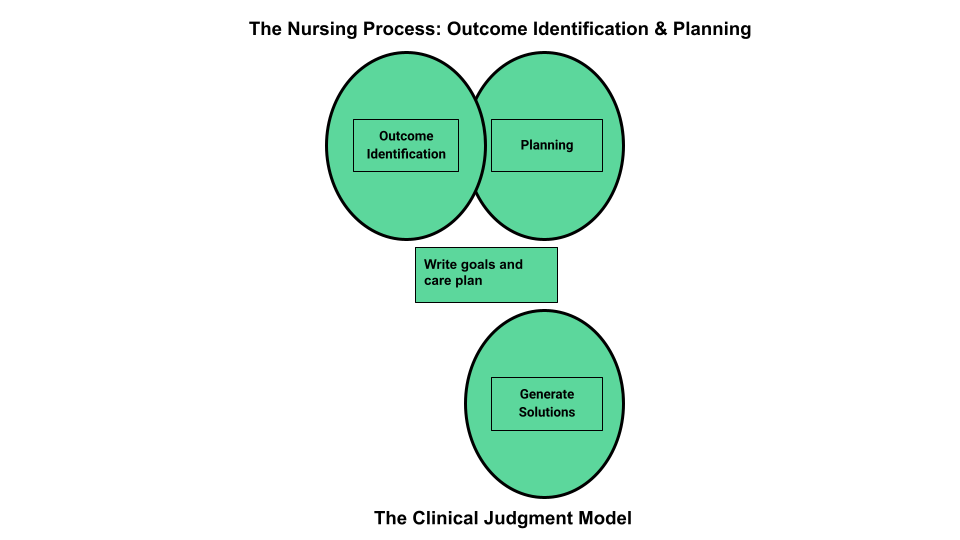

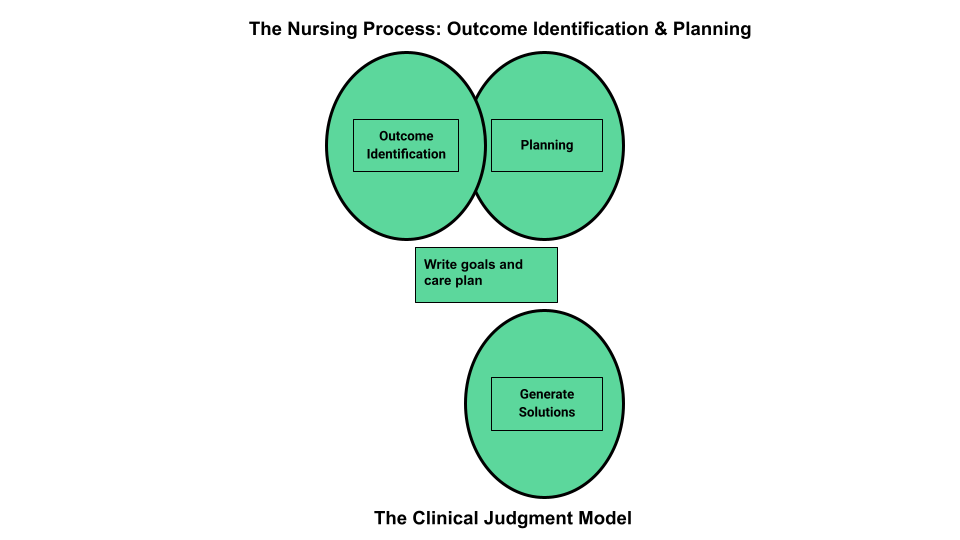

Outcome identification includes setting short- and long-term goals and then creating specific expected outcome statements for each nursing diagnosis. See Figure 4.9a[3] for an illustration of how the Outcome Identification phase of the nursing process correlates to the NCSBN Clinical Judgment Model.

Short-Term and Long-Term Goals

Nursing care should always be individualized and client centered. No two people are the same, and neither should nurse care plans be the same for two people. Goals and outcomes should be tailored specifically to each client’s needs, values, and cultural beliefs. Clients and family members should be included in the goal-setting process when feasible. Involving clients and family members promotes awareness of identified needs, ensures realistic goals, and motivates their participation in the treatment plan to achieve the mutually agreed upon goals and live life to the fullest with their current condition.

The nursing care plan is a road map used to guide client care so that all health care providers are moving toward the same client goals. Goals are broad statements of purpose that describe the overall aim of care. Goals can be short- or long-term. The time frame for short- and long-term goals is dependent on the setting in which the care is provided. For example, in a critical care area, a short-term goal might be set to be achieved within an 8-hour nursing shift, and a long-term goal might be in 24 hours. In contrast, in an outpatient setting, a short-term goal might be set to be achieved within one month and a long-term goal might be within six months.

A nursing goal is the overall direction in which the client must progress to improve the problem/nursing diagnosis and is often the opposite of the problem.

Example of a Broad Goal

Refer to Scenario C in the "Assessment" section of this chapter. Ms. J. had a priority nursing diagnosis of Excess Fluid Volume. A broad goal would be, “Ms. J. will achieve a state of fluid balance.”

Expected Outcomes

Goals are broad, general statements, but outcomes are specific and measurable. Expected outcomes are statements of measurable action for the client within a specific time frame that are responsive to nursing interventions. Nurses may create expected outcomes independently or refer to classification systems for assistance.

Client-Centered

Outcome statements are always client-centered. They should be developed in collaboration with the client and individualized to meet a client’s unique needs, values, and cultural beliefs. They should start with the phrase “The client will…” Outcome statements should be directed at resolving the defining characteristics the client is exhibiting for the nursing diagnosis. Additionally, the outcome must be something the client would like to achieve.

Outcome statements should contain five components easily remembered using the "SMART" mnemonic:[4]

- Specific

- Measurable

- Attainable/Action oriented

- Relevant/Realistic

- Timeframe

See Figure 4.9b[5] for an image of the SMART components of outcome statements. Each of these components is further described in the following subsections.

Specific

Outcome statements should state precisely what is to be accomplished. See examples of a not specific and a specific outcome in the following box.

Example

- Not specific outcome: "The client will increase the amount of exercise."

- Revised as a specific outcome: "The client will participate in a bicycling exercise session daily for 30 minutes."

Additionally, only one action should be included in each expected outcome. See examples in the following box.

Example

- More than one action: "The client will walk 50 feet three times a day with standby assistance of one and will shower in the morning until discharge" is actually two goals written as one. The outcome of ambulation should be separate from showering for precise evaluation. For instance, the client could shower but not ambulate, which would make this outcome statement very difficult to effectively evaluate.

- Revised to create two outcome statements so each can be measured: The client will walk 50 feet three times a day with standby assistance of one until discharge. The client will shower every morning until discharge.

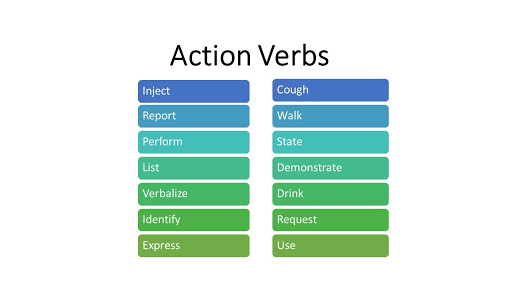

Measurable

Measurable outcomes have numeric parameters or other concrete methods of judging whether the outcome was met. It is important to use objective data to measure outcomes. If terms like “acceptable” or “normal” are used in an outcome statement, it is difficult to determine whether the outcome is attained. Refer to Figure 4.10[6] for examples of verbs that are measurable and not measurable in outcome statements.

Examples of a non-measurable outcome revised to a measurable outcome is described in the following box.

Example

- Not measurable outcome: "The client will drink adequate fluid amounts every shift."

- Revised into a measurable outcome: "The client will drink 24 ounces of fluids during every day shift (0600-1400)."

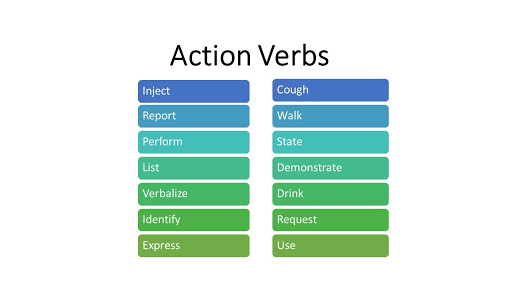

Action-Oriented and Attainable

Outcome statements should be written so that there is a clear action to be taken by the client or significant others. This means that the outcome statement should include a verb. Refer to Figure 4.11[7] for examples of action verbs.

An example of a non-action-oriented outcome revised to an action-oriented outcome is provided in the following box.

Example

- Not action-oriented outcome: "The client will get increased physical activity."

- Revised into an action-oriented outcome: "The client will list three types of aerobic activity that he would enjoy completing every week."

Realistic and Relevant

Realistic outcomes consider the client’s physical and mental condition; their cultural and spiritual values, beliefs, and preferences; and their socioeconomic status in terms of their ability to attain these outcomes. Consideration should be also given to disease processes and the effects of conditions such as pain and decreased mobility on the client's ability to reach expected outcomes. Other barriers to outcome attainment may be related to health literacy or lack of available resources. Outcomes should always be reevaluated and revised for attainability as needed. If an outcome is not attained, it is commonly because the original time frame was too ambitious, or the outcome was not realistic for the client.

See an example of how to revise an outcome that is not realistic into a realistic outcome in the following box.

Example

- Not realistic outcome: "The client will jog one mile every day when starting the exercise program."

- Revised into a realistic outcome: "The client will walk ½ mile three times a week for two weeks."

Time Limited

Outcome statements should include a time frame for evaluation. The time frame depends on the intervention and the client's current condition. Some outcomes may need to be evaluated every shift, whereas other outcomes may be evaluated daily, weekly, or monthly. During the evaluation phase of the nursing process, the outcomes will be assessed according to the time frame specified for evaluation. If it has not been met, the nursing care plan should be revised.

See an example an outcome that is not time limited revised into a time limited outcome in the following box.

Example

- Not time limited: "The client will stop smoking cigarettes."

- Time limited: "The client will complete the smoking cessation plan by December 12, 2025."

Putting It Together

An example of a SMART outcome for Scenario C is provided in the following box.

Example of a SMART Expected Outcome

Refer to Scenario C in the "Assessment" section of this chapter. Ms. J.’s priority nursing diagnosis statement was Excess Fluid Volume related to excess fluid intake as manifested by bilateral basilar crackles in the lungs, bilateral 2+ pitting edema of the ankles and feet, an increase weight of ten pounds, and the client reports, “My ankles are so swollen.”

The broad goal was, “Ms. J. will achieve a state of fluid balance.”

An example of a SMART expected outcome to achieve this broad goal is, “The client will have clear bilateral lung sounds within the next 24 hours.”

Outcome Identification is the third step of the nursing process (and the third Standard of Practice by the American Nurses Association). This standard is defined as, "The registered nurse identifies expected outcomes for a plan individualized to the health care consumer or the situation." The RN collaborates with the health care consumer, interprofessional team, and others to identify expected outcomes integrating the health care consumer's culture, values, and ethical considerations. Expected outcomes are documented as measurable goals with a time frame for attainment.[8] Outcome identification is performed by RNs and is outside the scope of practice for LPN/VNs, but LPN/VNs must be aware of expected outcomes for clients in their nursing care plan.

An outcome is a measurable behavior demonstrated response to nursing interventions.[9]Outcomes should be identified before nursing interventions are planned. After nursing interventions are implemented, the nurse will evaluate if the outcomes were met in the time frame indicated for that client.

Outcome identification includes setting short- and long-term goals and then creating specific expected outcome statements for each nursing diagnosis. See Figure 4.9a[10] for an illustration of how the Outcome Identification phase of the nursing process correlates to the NCSBN Clinical Judgment Model.

Short-Term and Long-Term Goals

Nursing care should always be individualized and client centered. No two people are the same, and neither should nursing care plans be the same for two people. Goals and outcomes should be tailored specifically to each client’s needs, values, and cultural beliefs. Clients and family members should be included in the goal-setting process when feasible. Involving clients and family members promotes awareness of identified needs, ensures realistic goals, and motivates their participation in the treatment plan to achieve the mutually agreed upon goals and live life to the fullest with their current condition.

The nursing care plan is a road map used to guide client care so that all health care providers are moving toward the same client goals. Goals are broad statements of purpose that describe the overall aim of care. Goals can be short- or long-term. The time frame for short- and long-term goals is dependent on the setting in which the care is provided. For example, in a critical care area, a short-term goal might be set to be achieved within an 8-hour nursing shift, and a long-term goal might be in 24 hours. In contrast, in an outpatient setting, a short-term goal might be set to be achieved within one month and a long-term goal might be within six months.

A nursing goal is the overall direction in which the client must progress to improve the problem/nursing diagnosis and is often the opposite of the problem.

Example of a Broad Goal

Refer to Scenario C in the "Assessment" section of this chapter. Ms. J. had a priority nursing diagnosis of Excess Fluid Volume. A broad goal would be, “Ms. J. will achieve a state of fluid balance.”

Expected Outcomes

Goals are broad, general statements, but outcomes are specific and measurable. Expected outcomes are statements of measurable action for the client within a specific time frame that are responsive to nursing interventions. Nurses may create expected outcomes independently or refer to classification systems for assistance.

Client-Centered

Outcome statements are always client-centered. They should be developed in collaboration with the client and individualized to meet a client’s unique needs, values, and cultural beliefs. They should start with the phrase “The client will…” Outcome statements should be directed at resolving the defining characteristics the client is exhibiting for the nursing diagnosis. Additionally, the outcome must be something the client would like to achieve.

Outcome statements should contain five components easily remembered using the "SMART" mnemonic:[11]

- Specific

- Measurable

- Attainable/Action oriented

- Relevant/Realistic

- Timeframe

See Figure 4.9b[12] for an image of the SMART components of outcome statements. Each of these components is further described in the following subsections.

Specific

Outcome statements should state precisely what is to be accomplished. See examples of a not specific and a specific outcome in the following box.

Example

- Not specific outcome: "The client will increase the amount of exercise."

- Revised as a specific outcome: "The client will participate in a bicycling exercise session daily for 30 minutes."

Additionally, only one action should be included in each expected outcome. See examples in the following box.

Example

- More than one action: "The client will walk 50 feet three times a day with standby assistance of one and will shower in the morning until discharge" is actually two goals written as one. The outcome of ambulation should be separate from showering for precise evaluation. For instance, the client could shower but not ambulate, which would make this outcome statement very difficult to effectively evaluate.

- Revised to create two outcome statements so each can be measured: The client will walk 50 feet three times a day with standby assistance of one until discharge. The client will shower every morning until discharge.

Measurable

Measurable outcomes have numeric parameters or other concrete methods of judging whether the outcome was met. It is important to use objective data to measure outcomes. If terms like “acceptable” or “normal” are used in an outcome statement, it is difficult to determine whether the outcome is attained. Refer to Figure 4.10[13] for examples of verbs that are measurable and not measurable in outcome statements.

Examples of a non-measurable outcome revised to a measurable outcome is described in the following box.

Example

- Not measurable outcome: "The client will drink adequate fluid amounts every shift."

- Revised into a measurable outcome: "The client will drink 24 ounces of fluids during every day shift (0600-1400)."

Action-Oriented and Attainable

Outcome statements should be written so that there is a clear action to be taken by the client or significant others. This means that the outcome statement should include a verb. Refer to Figure 4.11[14] for examples of action verbs.

An example of a non-action-oriented outcome revised to an action-oriented outcome is provided in the following box.

Example

- Not action-oriented outcome: "The client will get increased physical activity."

- Revised into an action-oriented outcome: "The client will list three types of aerobic activity that he would enjoy completing every week."

Realistic and Relevant

Realistic outcomes consider the client’s physical and mental condition; their cultural and spiritual values, beliefs, and preferences; and their socioeconomic status in terms of their ability to attain these outcomes. Consideration should be also given to disease processes and the effects of conditions such as pain and decreased mobility on the client's ability to reach expected outcomes. Other barriers to outcome attainment may be related to health literacy or lack of available resources. Outcomes should always be reevaluated and revised for attainability as needed. If an outcome is not attained, it is commonly because the original time frame was too ambitious, or the outcome was not realistic for the client.

See an example of how to revise an outcome that is not realistic into a realistic outcome in the following box.

Example

- Not realistic outcome: "The client will jog one mile every day when starting the exercise program."

- Revised into a realistic outcome: "The client will walk ½ mile three times a week for two weeks."

Time Limited

Outcome statements should include a time frame for evaluation. The time frame depends on the intervention and the client's current condition. Some outcomes may need to be evaluated every shift, whereas other outcomes may be evaluated daily, weekly, or monthly. During the evaluation phase of the nursing process, the outcomes will be assessed according to the time frame specified for evaluation. If it has not been met, the nursing care plan should be revised.

See an example an outcome that is not time limited revised into a time limited outcome in the following box.

Example

- Not time limited: "The client will stop smoking cigarettes."

- Time limited: "The client will complete the smoking cessation plan by December 12, 2025."

Putting It Together

An example of a SMART outcome for Scenario C is provided in the following box.

Example of a SMART Expected Outcome

Refer to Scenario C in the "Assessment" section of this chapter. Ms. J.’s priority nursing diagnosis statement was Excess Fluid Volume related to excess fluid intake as manifested by bilateral basilar crackles in the lungs, bilateral 2+ pitting edema of the ankles and feet, an increase weight of ten pounds, and the client reports, “My ankles are so swollen.”

The broad goal was, “Ms. J. will achieve a state of fluid balance.”

An example of a SMART expected outcome to achieve this broad goal is, “The client will have clear bilateral lung sounds within the next 24 hours.”