7.3 Common Conditions of the Head and Neck

Ernstmeyer & Christman - Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

Headache

A headache is a common type of pain that patients experience in everyday life and a major reason for missed time at work or school. Headaches range greatly in severity of pain and frequency of occurrence. For example, some patients experience mild headaches once or twice a year, whereas others experience disabling migraine headaches more than 15 days a month. Severe headaches such as migraines may be accompanied by symptoms of nausea or increased sensitivity to noise or light. Primary headaches occur independently and are not caused by another medical condition. Migraine, cluster, and tension-type headaches are types of primary headaches. Secondary headaches are symptoms of another health disorder that causes pain-sensitive nerve endings to be pressed on or pulled out of place. They may result from underlying conditions including fever, infection, medication overuse, stress or emotional conflict, high blood pressure, psychiatric disorders, head injury or trauma, stroke, tumors, and nerve disorders such as trigeminal neuralgia, a chronic pain condition that typically affects the trigeminal nerve on one side of the cheek.[1]

Not all headaches require medical attention, but some types of headaches can signify a serious disorder and require prompt medical care. Symptoms of headaches that require immediate medical attention include a sudden, severe headache unlike any the patient has ever had; a sudden headache associated with a stiff neck; a headache associated with convulsions, confusion, or loss of consciousness; a headache following a blow to the head; or a persistent headache in a person who was previously headache free.[2]

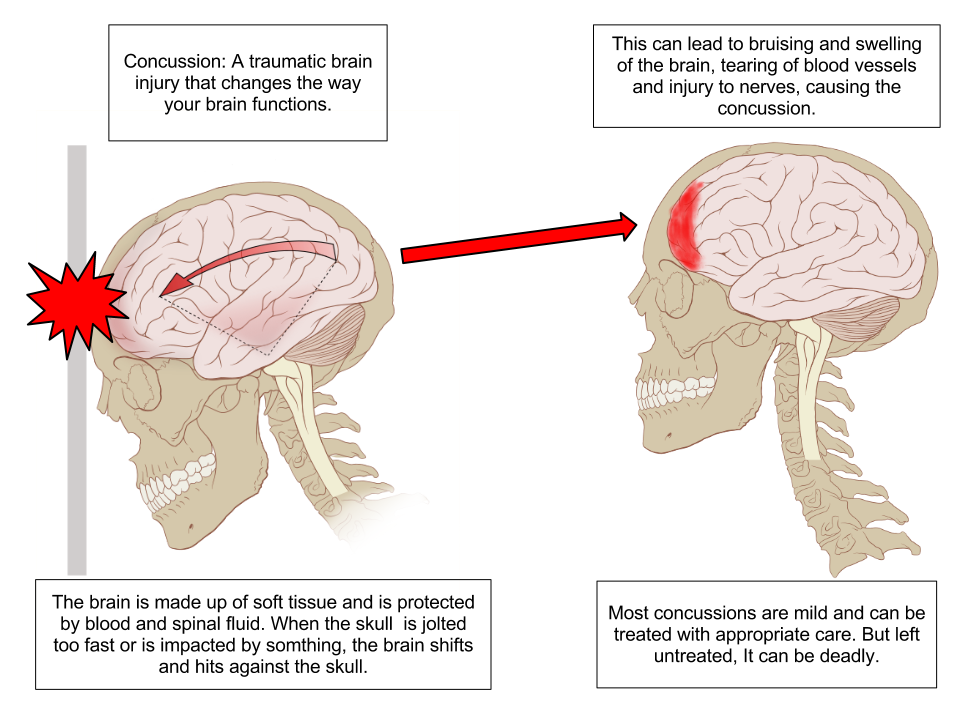

Concussion

A concussion is a type of traumatic brain injury caused by a blow to the head or by a hit to the body that causes the head and brain to move rapidly back and forth. This sudden movement causes the brain to bounce around in the skull, creating chemical changes in the brain and sometimes damaging brain cells.[3] See Figure 7.14[4] for an illustration of a concussion.

Review of Concussions on YouTube[5]

A person who has experienced a concussion may report the following symptoms:

- Headache or “pressure” in head

- Nausea or vomiting

- Balance problems or dizziness or double or blurry vision

- Light or noise sensitivity

- Feeling sluggish, hazy, foggy, or groggy

- Confusion, concentration, or memory problems

- Just not “feeling right” or “feeling down”[6]

The following signs may be observed in someone who has experienced a concussion:

- Can’t recall events prior to or after a hit or fall

- Appears dazed or stunned

- Forgets an instruction, is confused about an assignment or position, or is unsure of the game, score, or opponent

- Moves clumsily

- Answers questions slowly

- Loses consciousness (even briefly)

- Shows mood, behavior, or personality changes[7]

Anyone suspected of experiencing a concussion should immediately be seen by a health care provider or go to the emergency department for further testing.

Read more information about concussion signs and symptoms on the CDC’s Concussion Signs and Symptoms webpage.

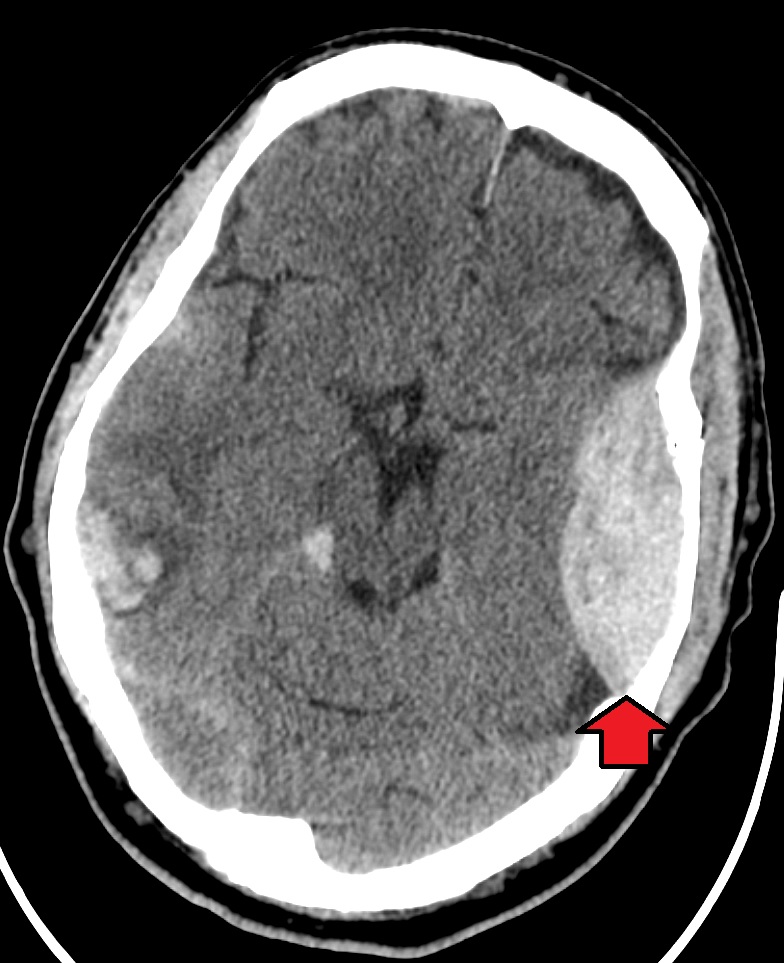

Head Injury

Head and traumatic brain injuries are major causes of immediate death and disability. Falls are the most common cause of head injuries in young children (ages 0–4 years), adolescents (15–19 years), and the elderly (over 65 years). Strong blows to the brain case of the skull can produce fractures resulting in bleeding inside the skull. A blow to the lateral side of the head may fracture the bones of the pterion. If the underlying artery is damaged, bleeding can cause the formation of a hematoma (collection of blood) between the brain and interior of the skull. As blood accumulates, it will put pressure on the brain. Symptoms associated with a hematoma may not be apparent immediately following the injury, but if untreated, blood accumulation will continue to exert increasing pressure on the brain and can result in death within a few hours.[8]

See Figure 7.15[9] for an image of an epidural hematoma indicated by a red arrow associated with a skull fracture.

Sinusitis

Sinusitis is the medical diagnosis for inflamed sinuses that can be caused by a viral or bacterial infection. When the nasal membranes become swollen, the drainage of mucous is blocked and causes pain.

There are several types of sinusitis, including these types:

- Acute Sinusitis: Infection lasting up to 4 weeks

- Chronic Sinusitis: Infection lasting more than 12 weeks

- Recurrent Sinusitis: Several episodes of sinusitis within a year

Symptoms of sinusitis can include fever, weakness, fatigue, cough, and congestion. There may also be mucus drainage in the back of the throat, called postnasal drip. Health care providers diagnose sinusitis based on symptoms and an examination of the nose and face. Treatments include antibiotics, decongestants, and pain relievers.[10]

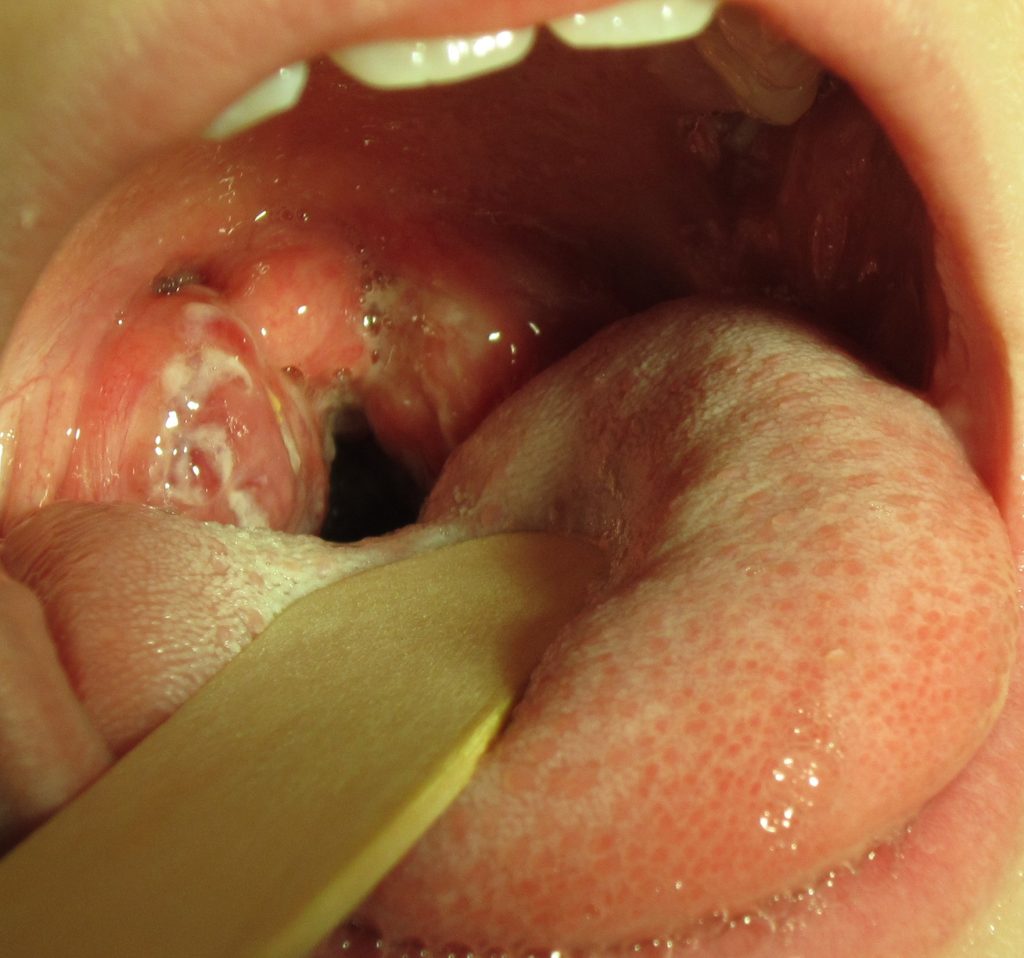

Pharyngitis

Pharyngitis is the medical term used for infection and/or inflammation in the back of the throat (pharynx). Common causes of pharyngitis are the cold viruses, influenza, strep throat caused by group A streptococcus, and mononucleosis. Strep throat typically causes white patches on the tonsils with a fever and enlarged lymph nodes. It must be treated with antibiotics to prevent potential complications in the heart and kidneys. See Figure 7.16[11] for an image of strep throat in a child.

If not diagnosed as strep throat, most cases of pharyngitis are caused by viruses, and the treatment is aimed at managing the symptoms. Nurses can teach patients the following ways to decrease the discomfort of a sore throat:

- Drink soothing liquids such as lemon tea with honey or ice water.

- Gargle several times a day with warm salt water made of 1/2 tsp. of salt in 1 cup of water.

- Suck on hard candies or throat lozenges.

- Use a cool-mist vaporizer or humidifier to moisten the air.

- Try over-the-counter pain medicines, such as acetaminophen.[12]

Epistaxis

Epistaxis, the medical term for a nosebleed, is a common problem affecting up to 60 million Americans each year. Although most cases of epistaxis are minor and manageable with conservative measures, severe cases can become life-threatening if the bleeding cannot be stopped.[13] See Figure 7.17[14] for an image of a severe case of epistaxis.

The most common cause of epistaxis is dry nasal membranes in winter months due to low temperatures and low humidity. Other common causes are picking inside the nose with fingers, trauma, anatomical deformity, high blood pressure, and clotting disorders. Medications associated with epistaxis are aspirin, clopidogrel, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and anticoagulants.[15]

To treat a nosebleed, have the victim lean forward at the waist and pinch the lateral sides of the nose with the thumb and index finger for up to 15 minutes while breathing through the mouth.[16] Continued bleeding despite this intervention requires urgent medical intervention such as nasal packing.

Cleft Lip and Palate

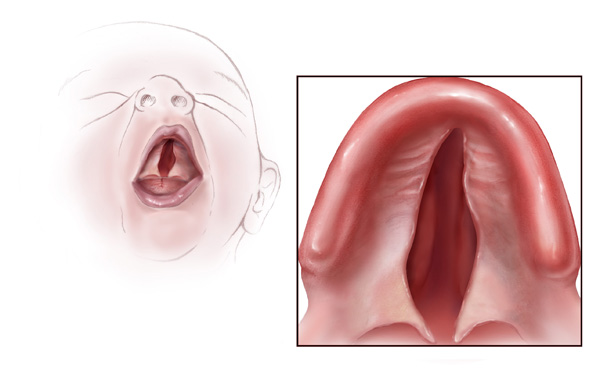

During embryonic development, the right and left maxilla bones come together at the midline to form the upper jaw. At the same time, the muscle and skin overlying these bones join together to form the upper lip. Inside the mouth, the palatine processes of the maxilla bones, along with the horizontal plates of the right and left palatine bones, join together to form the hard palate. If an error occurs in these developmental processes, a birth defect of cleft lip or cleft palate may result.

Cleft lip is a common developmental defect that affects approximately 1:1,000 births, most of which are male. This defect involves a partial or complete failure of the right and left portions of the upper lip to fuse together, leaving a cleft (gap). See Figure 7.18[17] for an image of an infant with a cleft lip.

A more severe developmental defect is a cleft palate that affects the hard palate, the bony structure that separates the nasal cavity from the oral cavity. See Figure 7.19[18] for an illustration of a cleft palate. Cleft palate affects approximately 1:2,500 births and is more common in females. It results from a failure of the two halves of the hard palate to completely come together and fuse at the midline, thus leaving a gap between the nasal and oral cavities. In severe cases, the bony gap continues into the anterior upper jaw where the alveolar processes of the maxilla bones also do not properly join together above the front teeth. If this occurs, a cleft lip will also be seen. Because of the communication between the oral and nasal cavities, a cleft palate makes it very difficult for an infant to generate the suckling needed for nursing, thus creating risk for malnutrition. Surgical repair is required to correct a cleft palate.[19]

Poor Oral Health

Despite major improvements in oral health for the population as a whole, oral health disparities continue to exist for many racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic groups in the United States. Healthy People 2020, a nationwide initiative geared to improve the health of Americans, identified improved oral health as a health care goal. A growing body of evidence has also shown that periodontal disease is associated with negative systemic health consequences. Periodontal diseases are infections and inflammation of the gums and bone that surround and support the teeth. Red, swollen, and bleeding gums are signs of periodontal disease. Other symptoms of periodontal disease include bad breath, loose teeth, and painful chewing.[20] In 2020, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that 42% of U.S. adults have some form of periodontitis, and almost 60% of adults aged 65 and older have periodontitis. See Figure 7.20[21] for an image of a patient with periodontal disease. Nurses may encounter patients who complain of bleeding gums, or they may discover other signs of periodontal disease during a physical assessment.

Because many Americans lack access to oral care, it is important for nurses to perform routine oral assessment and identify needs for follow-up. If signs and/or symptoms indicate potential periodontal disease, the patient should be referred to a dental health professional for a more thorough evaluation.[22]

Thrush/Candidiasis

Candidiasis is a fungal infection caused by Candida. Candida normally lives on the skin and inside the body without causing any problems, but it can multiply and cause an infection if the environment inside the mouth, throat, or esophagus changes in a way that encourages fungal growth.[23] See Figure 7.21[24] for an image of candidiasis.

Candidiasis in the mouth and throat can have many symptoms, including the following:

- White patches on the inner cheeks, tongue, roof of the mouth, and throat

- Redness or soreness

- Cotton-like feeling in the mouth

- Loss of taste

- Pain while eating or swallowing

- Cracking and redness at the corners of the mouth[25]

Candidiasis in the mouth or throat is common in babies but is uncommon in healthy adults. Risk factors for getting candidiasis as an adult include the following:

- Wearing dentures

- Diabetes

- Cancer

- HIV/AIDS

- Taking antibiotics or corticosteroids including inhaled corticosteroids for conditions like asthma

- Taking medications that cause dry mouth or have medical conditions that cause dry mouth

- Smoking

The treatment for mild to moderate cases of candidiasis infections in the mouth or throat is typically an antifungal medicine applied to the inside of the mouth for 7 to 14 days, such as clotrimazole, miconazole, or nystatin.

“Meth Mouth”

The use of methamphetamine (i.e., meth), a strong stimulant drug, has become an alarming public health issue in the United States. A common sign of meth abuse is extreme tooth and gum decay often referred to as “Meth Mouth.” See Figure 7.22[26] for an image of Meth Mouth.

Signs of Meth Mouth include the following:

- Dry Mouth. Methamphetamines dry out the salivary glands, and the acid content in the mouth will start to destroy the enamel on the teeth. Eventually this will lead to cavities.

- Cracked Teeth. Methamphetamine can make the user feel anxious, hyper, or nervous, so they clench or grind their teeth. You may see severe wear patterns on their teeth.

- Tooth Decay. Methamphetamine users crave beverages high in sugar while they are “high.” The bacteria that feed on the sugars in the mouth will secrete acid, which can lead to more tooth destruction. With methamphetamine users, tooth decay will start at the gum line and eventually spread throughout the tooth. The front teeth are usually destroyed first.

- Gum Disease. Methamphetamine users do not seek out regular dental treatment. Lack of oral health care can contribute to periodontal disease. Methamphetamines also cause the blood vessels that supply the oral tissues to shrink in size, reducing blood flow, causing the tissues to break down.

- Lesions. Users who smoke methamphetamine may present with lesions and/or burns on their lips or gingival inside the cheeks or on the hard palate. Users who snort may present with burns in the back of their throats.[27]

Nurses who notice possible signs of “Meth Mouth” should report their concerns to the health care provider, not only for a referral for dental care, but also for treatment of suspected substance abuse.

Dysphagia

Dysphagia is the medical term for difficulty swallowing that can be caused by many medical conditions. Nurses are often the first health care professionals to notice a patient’s difficulty swallowing as they administer medications or monitor food intake. Early identification of dysphagia, especially after a patient has experienced a cerebrovascular accident (i.e., stroke) or other head injury, helps to prevent aspiration pneumonia.[28] Aspiration pneumonia is a type of lung infection caused by material from the stomach or mouth entering the lungs and can be life-threatening.

Signs of dysphagia include the following:

- Coughing during or right after eating or drinking

- Wet or gurgly sounding voice during or after eating or drinking

- Extra effort or time required to chew or swallow

- Food or liquid leaking from mouth

- Food getting stuck in the mouth

- Difficulty breathing after meals[29]

The Barnes-Jewish Hospital-Stroke Dysphagia Screen (BJH-SDS) is an example of a simple, evidence-based bedside screening tool that can be used by nursing staff to efficiently identify swallowing impairments in patients who have experienced a stroke. See internet resource below for an image of the dysphagia screening tool. The result of the screening test is recorded as a “fail” if any of the five items tested are abnormal (Glasgow Coma Scale < 13, facial/tongue/palatal asymmetry or weakness, or signs of aspiration on the 3-ounce water test) or “pass” if all five items tested were normal. Patients with a failed screening result are placed on nothing-by-mouth (NPO) status until further evaluation is completed by a speech therapist. For more information about using the Glasgow Coma Scale, see the “Assessing Mental Status” section in the “Neurological Assessment” chapter.

View a PDF sample of a Nursing Bedside Swallow Screen.

Enlarged Lymph Nodes

Lymphadenopathy is the medical term for swollen lymph nodes. In a child, a node is considered enlarged if it is more than 1 centimeter (0.4 inch) wide. See Figure 7.23[30] for an image of an enlarged cervical lymph node.

Common infections such as a cold, pharyngitis, sinusitis, mononucleosis, strep throat, ear infection, or infected tooth often cause swollen lymph nodes. However, swollen lymph nodes can also signify more serious conditions. Notify the health care provider if the patient’s lymph nodes have the following characteristics:

- Do not decrease in size after several weeks or continue to get larger

- Are red and tender

- Feel hard, irregular, or fixed in place

- Are associated with night sweats or unexplained weight loss

- Are larger than 1 centimeter in diameter

The health care provider may order blood tests, a chest X-ray, or a biopsy of the lymph node if these signs occur.[31]

Thyroid

The thyroid is a butterfly-shaped gland located at the front of the neck that controls many of the body’s important functions. The thyroid gland makes hormones that affect breathing, heart rate, digestion, and body temperature. If the thyroid makes too much or not enough thyroid hormone, many body systems are affected. In hypothyroidism, the thyroid gland doesn’t produce enough hormone and many body functions slow down. When the thyroid makes too much hormone, a condition called hyperthyroidism, many body systems speed up.[32]

A goiter is an abnormal enlargement of the thyroid gland that can occur with hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism. If you find a goiter when assessing a patient’s neck, notify the health care provider for additional testing and treatment. See Figure 7.24[33] for an image of a goiter.

Media Attributions

- Concussion_Anatomy

- EpiduralHematoma

- Strep_throat2010

- Epistaxis1

- Cleftlipandpalate

- Cleft_palate

- Periodontal_Disease

- Human_tongue_infected_with_oral_candidiasis

- Suspectedmethmouth09-19-05closeup

- Cervical_lymphadenopathy_right_neck

- Swolen_feet_at_harefield_hospital_edema

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. (2019, December 31). Headache information page. https://www.ninds.nih.gov/Disorders/All-Disorders/Headache-Information-Page ↵

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. (2019, December 31). Headache information page. https://www.ninds.nih.gov/Disorders/All-Disorders/Headache-Information-Page ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019, February 12). Concussion signs and symptoms. https://www.cdc.gov/headsup/basics/concussion_symptoms.html ↵

- “Concussion Anatomy.png” by Max Andrews is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013, October 24). What is a concussion? [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://youtu.be/Sno_0Jd8GuA ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019, February 12). Concussion signs and symptoms. https://www.cdc.gov/headsup/basics/concussion_symptoms.html ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019, February 12). Concussion signs and symptoms. https://www.cdc.gov/headsup/basics/concussion_symptoms.html ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “EpiduralHeatoma.jpg” by James Heilman, MD is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- MedlinePlus [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US); [updated 2020, Aug 17]. Sinusitis; [updated 2020, Jun 10; reviewed 2016, Oct 26]; [cited 2020, Sep 4]; https://medlineplus.gov/sinusitis.html ↵

- “Strep throat2010.JPG” by James Heilman, MD is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020, May 1). Disparities in oral health. https://www.cdc.gov/OralHealth/oral_health_disparities/ ↵

- Fatakia, A., Winters, R., & Amedee, R. G. (2010). Epistaxis: A common problem. The Ochsner Journal, 10(3), 176–178. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3096213/ ↵

- “Epstaxis1.jpg” by Welleschik is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- Fatakia, A., Winters, R., & Amedee, R. G. (2010). Epistaxis: A common problem. The Ochsner Journal, 10(3), 176–178. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3096213/ ↵

- American Heart Association. (2000). Part 5: New guidelines for first aid. Circulation, 102(supplement 1). https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/circ.102.suppl_1.I-77 ↵

- “Cleftlipandpalate.JPG” by James Heilman, MD is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- “Cleft palate.jpg” by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is licensed under CC0 1.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Bencosme, J. (2018). Periodontal disease: What nurses need to know. Nursing, 48(7), 22-27. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.nurse.0000534088.56615.e4 ↵

- “Periodontal Disease.png” by Warren Schnider is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- Bencosme, J. (2018). Periodontal disease: What nurses need to know. Nursing, 48(7), 22-27. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.nurse.0000534088.56615.e4. ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020, June 15). Candida infections of the mouth, throat, and esophagus. https://www.cdc.gov/fungal/diseases/candidiasis/thrush/index.html ↵

- “Human tongue infected with oral candidiasis.jpg” by James Heilman, MD is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020, June 15). Candida infections of the mouth, throat, and esophagus. https://www.cdc.gov/fungal/diseases/candidiasis/thrush/index.html ↵

- “Suspectedmethmouth09-19-05closeup.jpg” by Dozenist is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- Maine Center for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.). Meth mouth. https://www.maine.gov/dhhs/mecdc/population-health/odh/documents/meth-mouth.pdf ↵

- Edmiaston, J., Connor, L. T., Steger-May, K., & Ford, A. L. (2014). A simple bedside stroke dysphagia screen, validated against videofluoroscopy, detects dysphagia and aspiration with high sensitivity. Journal of Stroke and Cerebrovascular Diseases: The Official Journal of National Stroke Association, 23(4), 712–716. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2013.06.030 ↵

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (n.d.). Swallowing disorders in adults. https://www.asha.org/public/speech/swallowing/Swallowing-Disorders-in-Adults/ ↵

- “Cervical lymphadenopathy right neck.png” by Coronation Dental Specialty Group is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- A.D.A.M. Medical Encyclopedia [Internet]. Johns Creek (GA): Ebix, Inc., A.D.A.M.; c1997-2020. Swollen lymph nodes; [updated 2020, Aug 25; cited 2020, Sep 4]; https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/003097.htm ↵

- National Institutes of Health. (2015). Thinking about your thyroid. https://newsinhealth.nih.gov/2015/09/thinking-about-your-thyroid ↵

- “Struma 00a.jpg” by Drahreg01 is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

A type of traumatic brain injury caused by a bump, blow, or jolt to the head or by a hit to the body that causes the head and brain to move rapidly back and forth. This sudden movement can cause the brain to bounce around or twist in the skull, creating chemical changes in the brain and damaging brain cells.

Inflamed sinuses caused by a viral or bacterial infection.

Learning Activities

(Answers to "Learning Activities" can be found in the "Answer Key" at the end of the book. Answers to interactive activity elements will be provided within the element as immediate feedback.)

![]()

Test your knowledge using this NCLEX Next Generation-style question. You may reset and resubmit your answers to this question an unlimited number of times.[2]

After establishing a culturally sensitive environment and performing a cultural assessment, nurses and nursing students can continue to promote culturally responsive care. Culturally responsive care includes creating a culturally safe environment, using cultural negotiation, and considering the impact of culture on clients’ time orientation, space orientation, eye contact, and food choices.

Culturally Safe Environment

A primary responsibility of the nurse is to ensure the environment is culturally safe for the client. A culturally safe environment is a safe space for clients to interact with the nurse, without judgment or discrimination, where the client is free to express their cultural beliefs, values, and identity. This responsibility belongs to both the individual nurse and also to the larger health care organization.

Cultural Negotiation

Many aspects of nursing care are influenced by the client’s cultural beliefs, as well as the beliefs of the health care culture. For example, the health care culture in the United States places great importance on punctuality for medical appointments, yet a client may belong to a culture that views “being on time” as relative. In some cultures, time is determined simply by whether it is day or night or time to wake up, eat, or sleep. Making allowances or accommodations for these aspects of a client’s culture is instrumental in fostering the nurse-client relationship. This accommodation is referred to as cultural negotiation. See Figure 3.6[3] for an image illustrating cultural negotiation. During cultural negotiation, both the client and nurse seek a mutually acceptable way to deal with competing interests of nursing care, prescribed medical care, and the client’s cultural needs. Cultural negotiation is reciprocal and collaborative. When a client’s cultural needs do not significantly or adversely affect their treatment plan, their cultural needs should be accommodated when feasible.

As an example, think about the client previously discussed for whom a fixed schedule is at odds with their cultural views. Instead of teaching the client to take a daily medication at a scheduled time, the nurse could explain that the client should take the medication every day when he awakens rather than every morning at 0800. Another example of cultural negotiation is illustrated by a scenario in which the nurse is preparing a client for a surgical procedure. As the nurse goes over the preoperative checklist, the nurse asks the client to remove her head covering (hijab). The nurse is aware that personal items should be removed before surgery; however, the client wishes to keep on the hijab. As an act of cultural negotiation and respect for the client’s cultural beliefs, the nurse makes arrangements with the surgical team to keep the client’s hijab in place for the surgical procedure and covering the client’s hijab with a surgical cap.

Decision-Making

Health care culture in the United States mirrors cultural norms of the country, with an emphasis on individuality, personal freedom, and self-determination. Self-determination refers to a person's right to determine what will be done with and to their own body. This perspective may conflict with a client whose cultural background values group decision-making and decisions made to benefit the group, not necessarily the individual. As an example, in the 2019 film The Farewell, a Chinese-American family decides to not tell the family matriarch she is dying of cancer and only has a few months left to live. The family keeps this secret from the woman in the belief that the family should bear the emotional burden of this knowledge, which is a collectivistic viewpoint in contrast to American individualistic viewpoint.

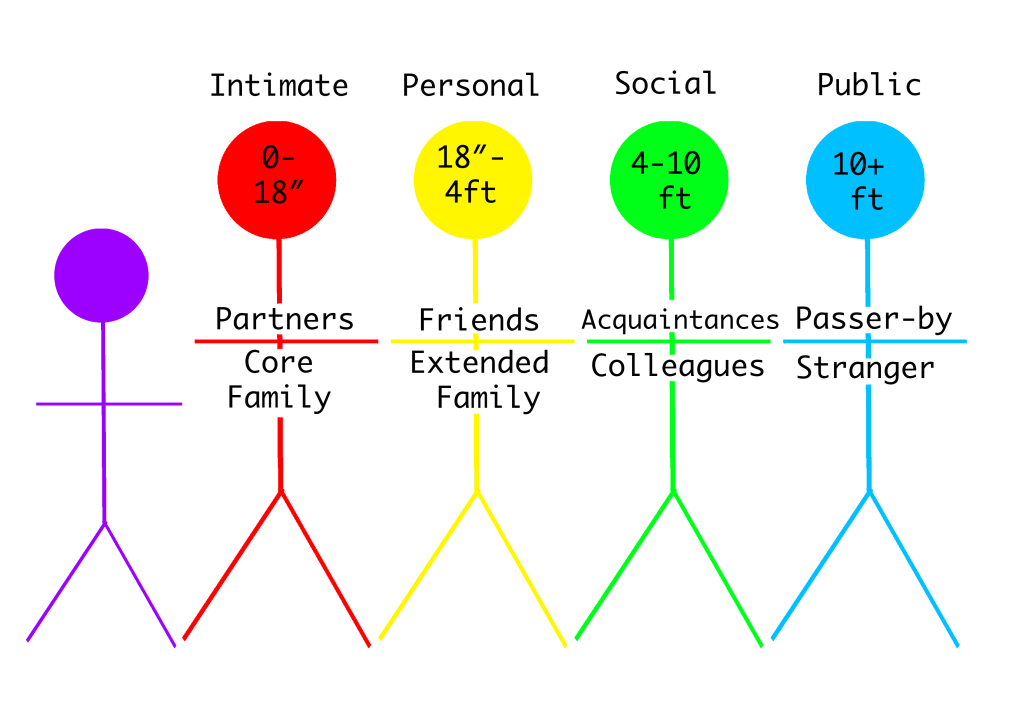

Space Orientation

The amount of space that a person surrounds themselves with to feel comfortable is influenced by culture. See Figure 3.7[4] for an image illustrating space orientation. For example, for some people, it would feel awkward to stand four inches away from another person while holding a social conversation, but for others a small personal space is expected when conversing with another.[5] There are times when a nurse must enter a client’s intimate or personal space, which can cause emotional distress for some clients. The nurse should always ask for permission before entering a client’s personal space and explain why close contact is necessary and what is about to happen.

Clients may also be concerned about their modesty or being exposed. A client may deal with the violation of their space by removing themselves from the situation, pulling away, or closing their eyes. The nurse should recognize these cues for what they are, an expression of cultural preference, and allow the client to assume a position or distance that is comfortable for them.

Similar to cultural influences on personal space, touch is also culturally determined. This has implications for nurses because depending on the culture, it may be inappropriate for a male nurse to provide care for a female client and vice versa. In some cultures, it is also considered rude to touch a person’s head without permission.

Review more information about space orientation in the "Communication" chapter.

Eye Contact

Eye contact is also a culturally mediated behavior. See Figure 3.8[6] for an image of eye contact. In the United States, direct eye contact is valued when communicating with others, but in some cultures, direct eye contact is interpreted as being rude or bold. Rather than making direct eye contact, a client may avert their eyes or look down at the floor to show deference and respect to the person who is speaking. The nurse should notice these cultural cues from the client and mirror the client’s behaviors when possible.

Food Choices

Culture plays a meaningful role in the dietary practices and food choices of many people. Food is used to celebrate life events and holidays. Most cultures have staple foods, such as bread, pasta, or rice and particular ways of preparing foods. See Figure 3.9[7] for an image of various food choices. Special foods are prepared to heal and to cure or to demonstrate kinship, caring, and love. For example, in the United States, chicken noodle soup is often prepared and provided to family members who are ill. In certain Asian cultures, individuals prefer "heating" or "cooling" foods depending on the illness, with the belief that each specific food will help bring balance back to their system.[8] Additionally, certain foods and beverages (such as meat and alcohol) are forbidden in some cultures. Nurses should accommodate or negotiate dietary requests of their clients, knowing that food holds such an important meaning to many people. See a summary of common food choices across cultures and religions in Table 3.8.

Table 3.8 Common Food Choices and Other Considerations Across Cultures and Religions[9], [10]

| Buddhist & Hindu | Christian | Hispanic | Hmong | Jewish | Muslim | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Common dietary choices | Lentils, tofu, vegetables, spices, and rice. | Varies across denominations. Some choose to eat fish on Friday rather than meat. | Rice, beans, pork, beef, chicken, goat, eggs, corn, avocado, and tropical fruits | Pho, laab, spring rolls, khao niew (sticky rice), rice, pork, chicken, beef, fish, tofu, leafy greens, tropical fruits | Kosher diet includes preparation of meat and dairy, kosher-certified foods | Halal diet prohibits pork and alcohol and permits only halal-certified meats |

| Other | Clients may practice vegetarianism and mindful eating practices. | During Lent, clients may fast or avoid certain foods. | Diet is often a blend of tradition and modern cuisine that dates back to the first agricultural communities, such as the Mayans & Aztec Empire. | During the postpartum period, clients may choose boiled chicken, rice, & warm/hot water for 30 days. |

During Yom Kippur, clients may fast for 24 hours. | During Ramadan, clients may fast from sunrise to sunset. |

Read more information about cultural dietary preferences and restrictions in the "Common Religions and Spiritual Practices" section of the "Spirituality" chapter.

Summary

In summary, there are several steps in the journey of becoming a culturally competent nurse with cultural humility who provides culturally responsive care to clients. As you continue in your journey of developing cultural competency, keep the summarized points in the following box in mind.

Summary of Developing Cultural Competency

- Cultural competence is an ongoing process for nurses and takes dedication, time, and practice to develop.

- Pursuing the goal of cultural competence in nursing and other health care disciplines is a key strategy in reducing health care disparities.

- Culturally competent nurses recognize that culture functions as a source of values and comfort for clients, their families, and communities.

- Culturally competent nurses intentionally provide client-centered care with sensitivity and respect for culturally diverse populations.

- Misunderstandings, prejudices, and biases on the part of the health care provider interfere with the client’s health outcomes.

- Culturally competent nurses negotiate care with clients so the care is congruent with their cultural beliefs and values.

- Nurses should examine their own biases, ethnocentric views, and prejudices so as not to interfere with the client’s care.

- Nurses who respect and understand the cultural values and beliefs of their clients are more likely to develop positive, trusting relationships with their clients.

Difficulty swallowing.

- Gather Supplies: Gown, mask, face shield, goggles, and alcohol-based sanitizer

- Procedure Steps:

- Face the back opening of the gown.

- Unfold the gown.

- Put your arms into the sleeves.

- Secure the neck opening at the back of your neck.

- Secure the waist, making sure that the back flaps overlap each other and covering your clothing as completely as possible.

- Put on a mask and, if needed, goggles or face shield.

- Put on gloves.

- Ensure the gloves overlap the gown sleeves at the wrist.

- When care is complete and before leaving the room, remove the gloves BEFORE removing the gown.

- Remove the gloves, turning them inside out.

- Dispose of the gloves in the appropriate container.

- Perform hand hygiene.

- Remove any goggles or face shield and place in the appropriate receptacle.

- Unfasten the gown at the neck.

- Unfasten the gown at the waist.

- Remove the gown starting at the top of the shoulders, turning it inside out and folding soiled area to soiled area.

- Dispose of the gown in an appropriate container.

- Remove the mask by grasping loop behind ear or untying at back of head.

- Perform hand hygiene.

Review the Sequence for putting on personal protective equipment PDF handout[11] from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) with current recommendations for putting on and removing PPE.

View a YouTube video[12] of an instructor demonstrating donning/doffing PPE with a mask and face shield or goggles:

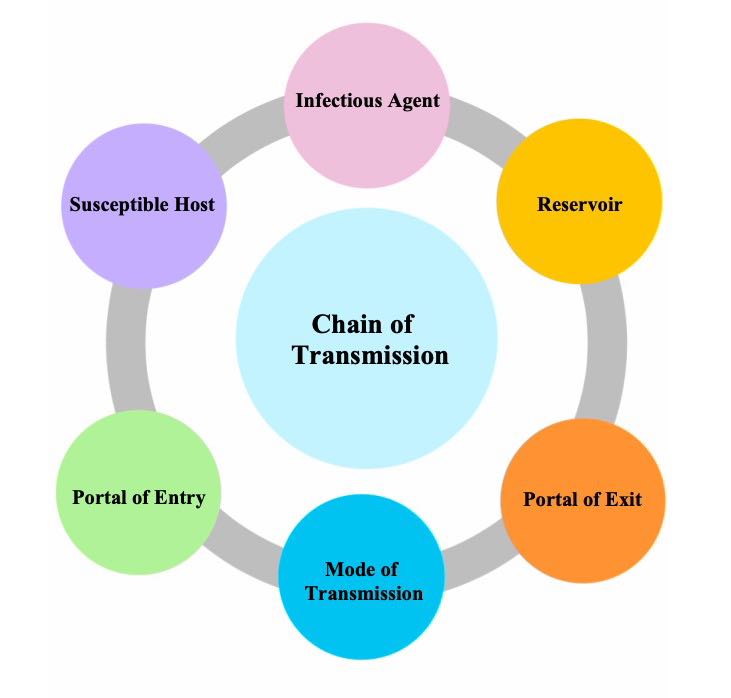

The chain of infection, also referred to as the chain of transmission, describes how an infection spreads based on these six links of transmission:

- Infectious Agent

- Reservoirs

- Portal of Exit

- Modes of Transmission

- Portal of Entry

- Susceptible Host

See Figure 4.1[13] for an illustration of the chain of infection. If any “link” in the chain of infection is removed or neutralized, transmission of infection will not occur. Health care workers must understand how an infectious agent spreads via the chain of transmission so they can break the chain and prevent the transmission of infectious disease. Routine hygienic practices, standard precautions, and transmission-based precautions are used to break the chain of transmission.

The links in the chain of infection include Infectious Agent, Reservoir, Portal of Exit, Mode of Transmission, Portal of Entry, and Susceptible Host[14]:

- Infectious Agent: Microorganisms, such as bacteria, viruses, fungi, or parasites, that can cause infectious disease.

- Reservoir: The host in which infectious agents live, grow, and multiply. Humans, animals, and the environment can be reservoirs. Examples of reservoirs are a person with a common cold, a dog with rabies, or standing water with bacteria. Sometimes a person may carry an infectious agent but is not symptomatic or ill. This is referred to as being colonized, and the person is referred to as a carrier. For example, many health care workers carry methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) bacteria in their noses but are not symptomatic.

- Portal of Exit: The route by which an infectious agent escapes or leaves the reservoir. In humans, the portal of exit is typically a mucous membrane or other opening in the skin. For example, pathogens that cause respiratory diseases usually escape through a person’s nose or mouth.

- Mode of Transmission: The way in which an infectious agent travels to other people and places because they cannot travel on their own. Modes of transmission include contact, droplet, or airborne transmission. For example, touching sheets with drainage from one person’s infected wound and then touching another person without washing one’s hands is an example of contact transmission of an infectious agent. Examples of droplet or airborne transmission are coughing and sneezing, depending on the size of the microorganism.

- Portal of Entry: The route by which an infectious agent enters a new host (i.e., the reverse of the portal of exit). For example, mucous membranes, skin breakdown, and artificial openings in the skin created for the insertion of medical equipment (such as intravenous lines) are at high risk for infection because they provide an open path for microorganisms to enter the body. Tubes inserted into mucous membranes, such as a urinary catheter, also facilitate the entrance of microorganisms into the body. A person’s immune system fights against infectious organisms that have entered the body through the use of nonspecific and specific defenses. Read more about defenses against microorganisms in the “Defenses Against Transmission of Infection” section of this chapter.

- Susceptible Host: A person at elevated risk for developing an infection when exposed to an infectious agent due to changes in their immune system defenses. For example, infants (up to 2 years old) and older adults (aged 65 or older) are at higher risk for developing infections due to underdeveloped or weakened immune systems. Additionally, anyone with chronic medical conditions (such as diabetes) are also at higher risk of developing an infection. In health care settings, almost every patient is considered a “susceptible host” because of preexisting illnesses, medical treatments, medical devices, or medications that increase their vulnerability to developing an infection when exposed to infectious agents in the health care environment. As caregivers, it is the NA's responsibility to protect susceptible patients by breaking the chain of infection.

After a susceptible host becomes infected, they become a reservoir that can then transmit the infectious agent to another person. If an individual’s immune system successfully fights off the infectious agent, they may not develop an infection, but instead the person may become an asymptomatic “carrier” who can spread the infectious agent to another susceptible host. For example, individuals exposed to COVID-19 may not develop an active respiratory infection but can spread the virus to other susceptible hosts via sneezing.

Learn more about the chain of infection by clicking on the following activities.

This H5P activity is a derivative of original activities by Michelle Hugues and licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0 unless otherwise noted.

This H5P activity is a derivative of original activities by Michelle Hugues and licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0 unless otherwise noted.

This H5P activity is a derivative of original activities by Michelle Hugues and licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0 unless otherwise noted.

This H5P activity is a derivative of original activities by Michelle Hugues and licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0 unless otherwise noted.

This H5P activity is a derivative of original activities by Michelle Hugues and licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0 unless otherwise noted.

This H5P activity is a derivative of original activities by Michelle Hugues and licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0 unless otherwise noted.

Putting It All Together

Note: To enlarge the print, you can expand the activity by clicking the arrows in the right upper corner of the text box. Please drag and drop the descriptors and actions into the appropriate boxes to demonstrate the various steps in the chain of infection.

This H5P activity is a derivative of original activities by Michelle Hugues and licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0 unless otherwise noted.

Healthcare-Acquired Infections

An infection that develops in an individual after being admitted to a health care facility or undergoing a medical procedure is a healthcare-associated infection (HAI), formerly referred to as a nosocomial infection. About 1 in 31 hospital patients develops at least one healthcare-associated infection every day. HAIs increase the cost of care and delay recovery. They are associated with permanent disability, loss of wages, and even death. An example of an HAI is a skin infection that develops in a patient’s incision after they had surgery due to improper hand hygiene of health care workers.[15],[16] It is important to understand the dangers of Healthcare-Acquired Infections and actions that can be taken to prevent them.

Read more details about healthcare-acquired infections in the "Infection" chapter of Open RN Nursing Fundamentals.

Healthcare-Associated Infections by Michelle Hughes is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

- Gather Supplies: Antiseptic hand rub

- Procedure Steps:

- Remove jewelry according to agency policy; push your sleeves above your wrists.

- Apply enough product into the palm of one hand and enough to cover your hands thoroughly per product directions.

- Rub your hands together, covering all surfaces of your hands and fingers with antiseptic until the alcohol is dry (a minimum of 30 seconds):

- Rub hands palm to palm

- Rub back of right and left hand (fingers interlaced)

- Rub palm to palm with fingers interlaced

- Perform rotational rubbing of left and right thumbs

- Rub your fingertips against the palm of your opposite hand

- Rub your wrists

- Repeat hand sanitizing sequence a minimum of two times.

- Repeat hand sanitizing sequence until the product is dry.

View a YouTube video[17] of an instructor demonstrating hand hygiene with alcohol-based hand sanitizer: