Toddler Years

A toddler is a child between 1 to 3 years old. Major physiological changes continue into the toddler years. Unlike in infancy, the limbs grow much faster than the trunk, which gives the body a more proportionate appearance. By the end of the third year, a toddler is taller and more slender than an infant, with a more erect posture. As the child grows, bone density increases and bone tissue gradually replaces cartilage. This process, known as ossification, is not completed until puberty.[1]

Developmental Milestones in a Toddler

Developmental milestones in a toddler include running, drawing, toilet training, and self-feeding. How a toddler acts, speaks, learns, and eats offers important clues about their development. By the age of two, children have advanced from infancy and are on their way to becoming school-aged children. Their physical growth and motor development slow compared to the progress they made as infants. However, toddlers experience enormous intellectual, emotional, and social changes. Of course, food and nutrition continue to play an important role in a child’s development. During this stage, the diet completely shifts from breastfeeding or bottle-feeding to solid foods along with healthy juices and other liquids. Parents of toddlers also need to be mindful of certain nutrition-related issues that may crop up during this stage of the human life cycle. For example, fluid requirements relative to body size are higher in toddlers than in adults because children are at greater risk of dehydration.

The toddler years pose interesting challenges for parents or other caregivers, as children learn how to eat on their own and begin to develop personal preferences. However, with the proper diet and guidance, toddlers can continue to grow and develop at a healthy rate.

Download the CDC’s Milestone Tracker App (opens in a new window) to see more photos and videos of milestones, track children’s development, and know what to do if you ever become concerned about a child’s development:

Nutritional Requirements

In the second year of life, toddlers consume less human milk, and infant formula is not recommended. Calories and nutrients should predominantly be met from a healthy diet of age-appropriate foods and beverages. For toddlers still consuming human milk (approximately one-third at 12 months and 15 percent at 18 months), a healthy dietary pattern should include a similar combination of nutrient-dense complementary foods and beverages.[2]

The USDA’s MyPlate online application may be used as a guide for toddlers (opens in a new window). A toddler’s serving sizes should be approximately one-quarter that of an adult’s. One way to estimate serving sizes for young children is one tablespoon for each year of life. For example, a two-year-old child would be served two tablespoons of fruits or vegetables at a meal, while a four-year-old would be given four tablespoons, or a quarter cup. Here is an example of a toddler-sized meal:

- 1 ounce of meat or chicken, or 2 to 3 tablespoons of beans

- One-quarter slice of whole-grain bread

- 1 to 2 tablespoons of cooked vegetables

- 1 to 2 tablespoons of fruit

Energy

The energy requirements for ages two to three are about 700 to 1,000-1400 calories per day, which is appropriate for most toddlers ages 12 through 23 months.[3] In general, a toddler needs to consume about 40 calories for every inch of height. For example, a young child who measures 32 inches should take in an average of 1,300 calories a day. However, the recommended caloric intake varies with each child’s activity level. Toddlers require small, frequent, nutritious snacks and meals to satisfy energy requirements. The amount of food a toddler needs from each food group depends on daily calorie needs. See Table 12.7 “Serving Sizes for Toddlers” for some examples.[4]

| Food Group | Daily Serving | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Grains | About 3-5 ounces of grains per day, ideally whole grains |

|

| Proteins | 2-4 ounces of meat, poultry, fish, eggs, or legumes |

|

| Fruits | 1-1.5 cups of fresh, frozen, canned, and/or dried fruits, or 100 percent fruit juice |

|

| Vegetables | 1-1.5 cups of raw and/or cooked vegetables |

|

| Dairy Products | 2-2.5 cups per day |

|

Macronutrients

For carbohydrate intake, the Acceptable Macronutrient Distribution Range (AMDR) is 45 to 65 percent of daily calories (113 to 163 grams for 1,000 daily calories). Toddlers’ needs increase to support their body and brain development. The RDA of protein is 5 to 20 percent of daily calories (13 to 50 grams for 1,000 daily calories). The AMDR for fat for toddlers is 30 to 40 percent of daily calories (33 to 44 grams for 1,000 daily calories). Essential fatty acids, along with nerve and other tissue types, are vital for the development of the eyes. However, toddlers should not consume foods with high amounts of trans fats and saturated fats. Instead, young children require the equivalent of 3 teaspoons of healthy oils, such as extra virgin cold-pressed olive oil, each day.

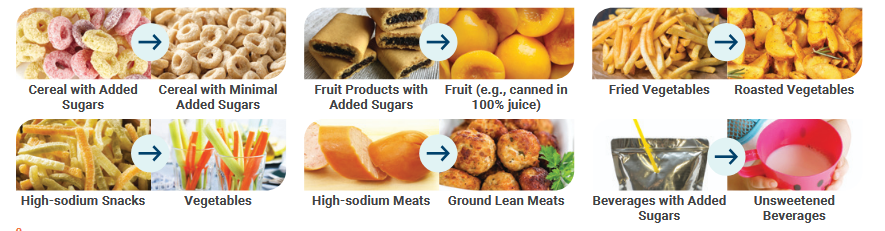

Due to toddlers’ relatively high nutrient needs, a healthy dietary pattern has virtually no room for added sugars. Toddlers consume more than 100 calories from added sugars daily, ranging from 40 to 250 calories a day (about 2.5 to 16 teaspoons). Sugar, sweetened beverages, particularly fruit drinks, contribute more than 25 percent of total added sugars intakes, and sweet bakery products contribute about 15 percent. Other food category sources contribute a smaller proportion of total added sugars on their own, but the wide variety of sources, which include yogurts, ready-to eat cereals, candy, fruits, flavored milk, milk substitutes, baby food products, and breads, points to the need to make careful choices across all foods.

According to the Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2020-2025, total grains, particularly refined grains, are consumed in amounts that exceed recommendations in toddlers. Conversely, intakes of whole grains fall short of recommended amounts for more than 95 percent of toddlers. Most grains are consumed through breads, rolls, tortillas, other bread products, or as part of a mixed dish. Ten percent of grains come from sweet bakery products, and approximately 15 percent come from crackers and savory snacks. Many of these categories are top sources of sodium or added sugars in this age group. The average intake of dairy foods, most consumed as milk, generally exceeds the recommended amounts in this age group. Intakes of yogurt and cheese account for about 10 percent of dairy intakes. Plant-based beverages and flavored milks make up about 2 percent of dairy intakes among toddlers. Protein foods intakes fall within the recommended range, on average. Intakes of meats, poultry, and eggs make up a majority of protein foods intakes, however, seafood intakes in this age group is low. Children in this age group can reduce sodium intake by eating less cured or processed meats, including hot dogs, deli meats, and sausages.[5]

Micronutrients

As a child grows, the demand for micronutrients increases. These needs for vitamins and minerals can be met with a balanced diet, with a few exceptions. According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, toddlers and children of all ages need 600 international units of vitamin D per day. Vitamin D-fortified milk and cereals can help to meet this need. However, toddlers who do not get enough of this micronutrient should receive a supplement. Pediatricians may also prescribe a fluoride supplement for toddlers who live in areas with fluoride-poor water. Iron deficiency is also a major concern for children between two and three. You will learn about iron-deficiency anemia later in this section.

Learning How to Handle Food

As children grow older, they enjoy caring for themselves, including self-feeding. During this phase, it is important to offer children foods they can handle on their own and help them avoid choking and other hazards. Examples include fresh fruits sliced into pieces, orange or grapefruit sections, peas or potatoes mashed for safety, a cup of yogurt, and whole-grain bread or bagels cut into pieces. Even with careful preparation and training, the learning process can be messy. As a result, parents and other caregivers can help children learn how to feed themselves by providing the following:

- small utensils that fit a young child’s hand

- small cups that will not tip over easily

- plates with edges to prevent food from falling off

- small servings on a plate

- high chairs, booster seats, or cushions to reach a table

Feeding Problems in the Toddler Years

During the toddler years, parents may face several problems related to food and nutrition. Possible obstacles include difficulty helping a young child overcome a fear of new foods, or fights over messy habits at the dinner table. Even in the face of problems and confrontations, parents and other caregivers must ensure their preschooler has nutritious choices at every meal. For example, even if a child stubbornly resists eating vegetables, parents should continue to provide them. Before long, the child may change their mind and develop a taste for foods once abhorred. It is important to remember that this is the time to establish or reinforce healthy habits.

Nutritionist Ellyn Satter states that feeding is a responsibility split between parent and child. According to Satter, parents are responsible for what their infants eat, while infants are responsible for how much they eat. In the toddler years and beyond, parents are responsible for what they offer their children to eat, when they eat, and where they eat, while children are responsible for how much food they eat and whether they eat. Satter states that the role of a parent or a caregiver in feeding includes the following: [6]

- Selecting and preparing food

- Providing regular meals and snacks

- Making mealtimes pleasant

- Showing children what they must learn about mealtime behavior

- Avoid letting children eat between meals or snack times

Picky Eaters

The parents of toddlers are likely to notice a sharp drop in their child’s appetite. Children at this stage are often picky about what they want to eat because they just aren’t as hungry. They may turn their heads away after eating just a few bites. Or, they may resist coming to the table at mealtimes. They can also be unpredictable about what they want to consume for specific meals or at particular times of the day. Although it may seem that toddlers should increase their food intake to match their activity level, there is a good reason for picky eating. A child’s growth rate slows after infancy, and toddlers ages two and three do not require as much food.

One way to encourage picky eaters to try healthy foods is to involve them in age-appropriate meal preparation tasks. Small toddlers can tear up lettuce leaves for a salad, or arrange fruit and cheese slices on a plate. Some Louisiana Recipes for Kids can be found at the following links (all links open in a new window):

- Louisiana cookbook blog with healthy recipes for children

- Easy Kid-Friendly Recipes from New Orleans

- Cajun and Creole Recipes to Make with Kids

Toddler Obesity

Another potential problem during the early childhood years is toddler obesity. According to the US Department of Health and Human Services, in the past thirty years, obesity rates have more than doubled for all children, including infants and toddlers.[7] For children, obesity is having a body mass index (BMI) at or above the 95th percentile for age and sex.[8]

(Source: USDA, Public Domain)

From 2017 to March 2020, the prevalence of obesity among U.S. children and adolescents was 19.7%.[9] This means that approximately 14.7 million U.S. youths aged 2–19 years have obesity. However, Improvement was shown among young children enrolled in the food assistance program in 41 U.S. states and territories. A study in 2019 show 41 U.S. states and territories show significant declines in obesity among children, aged 2-4 years, from low-income families enrolled in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) between 2010-2016.[10]

Obesity during early childhood tends to linger as a child matures and cause health problems later in life. There are many reasons for this growing problem. One is a lack of time. Parents and other caregivers who are constantly on the go may find it difficult to fit home-cooked meals into a busy schedule. They may turn to fast food and other conveniences that are quick and easy, but not nutritionally sound. Another contributing factor is a lack of access to fresh fruits and vegetables. This is a problem particularly in low-income neighborhoods where local stores and markets may not stock fresh produce or may have limited options. Physical inactivity is also a factor, as toddlers who live a sedentary lifestyle are more likely to be overweight or obese. Another contributor is a lack of breastfeeding support. Children who were breastfed as infants have lower rates of obesity than children who were bottle-fed.

To prevent or address toddler obesity, parents and caregivers can do the following:

- Eat at the kitchen table instead of in front of a television to monitor what and how much a child eats.

- Offer a child a healthy portion. The size of a toddler’s fist is an appropriate serving size.

- Plan time for physical activity, about sixty minutes or more per day. Toddlers should have no more than sixty minutes of sedentary activity per day, such as watching television.

Early Childhood Caries

Good dental health is critical to overall health, as well as the ability to chew foods properly. Early childhood caries is the most common chronic, infectious childhood disease worldwide and a health matter of utmost seriousness.[11]

Early childhood caries remain a potential problem during the toddler years. The risk of early childhood caries continues as children consume more foods with a high sugar content. According to the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, children between ages of two and five consume about 200 calories of added sugar per day.[12] Therefore, parents with toddlers should avoid processed foods, such as snacks from vending machines, and sugary beverages, such as soda. Parents also need to instruct a child on brushing their teeth at this time to help a toddler develop healthy habits and avoid tooth decay. Parents should be advised to start brushing their children’s teeth with a soft brush and fluoridated toothpaste when the first tooth erupts.[13] Generally, children need help brushing their teeth until they are 5 years old.

Iron-Deficiency Anemia

An infant who switches to solid foods but does not eat enough iron-rich foods can develop iron-deficiency anemia. This condition occurs when an iron-deprived body cannot produce enough hemoglobin, a protein in red blood cells that transports oxygen throughout the body. The inadequate supply of hemoglobin for new blood cells results in anemia. Iron-deficiency anemia causes a number of problems, including weakness, pale skin, shortness of breath, and irritability. It can also result in intellectual, behavioral, or motor problems. In infants and toddlers, iron-deficiency anemia can occur as young children are weaned from iron-rich foods, such as breast milk and iron-fortified formula. They begin to eat solid foods that may not provide enough of this nutrient. As a result, their iron stores become diminished at a time when this nutrient is critical for brain growth and development.

There are steps that parents and caregivers can take to prevent iron-deficiency anemia, such as adding more iron-rich foods to a child’s diet, including lean meats, fish, poultry, eggs, legumes, and iron-enriched whole-grain breads and cereals. A toddler’s diet should provide 7 to 10 milligrams of iron daily. Although milk is critical for the bone-building calcium that it provides, intake should not exceed the RDA to avoid displacing foods rich with iron. Children may also be given a daily supplement, using infant vitamin drops with iron or ferrous sulfate drops. If iron-deficiency anemia does occur, treatment includes a dosage of 3 milligrams per kilogram once daily before breakfast, usually in the form of a ferrous sulfate syrup. Consuming vitamin C, such as orange juice, can also help to improve iron absorption.[14]

American Academy of Pediatrics recommends the following: that universal screening be employed to identify anemia at 12 months of age using risk assessment and laboratory tests, that exclusively and partially breastfed infants receive 1 mg elemental iron/kg daily beginning at 4 months of age until iron-containing complementary foods are introduced, and that preterm breastfed infants receive 2 mg elemental iron/kg daily by 1 month of age until weaned to iron-fortified formula or beginning complementary foods.[15] Dietary advice to prevent or treat iron deficiency in children includes the following:[16]

Foods rich in iron

- High: meat and eggs

- Medium: meat alternatives (e.g., beans, tofu)

- Lower: grain products (e.g., oatmeal, enriched pasta, enriched rice), vegetables and fruit (e.g., broccoli, spinach, prune juice)

Foods containing vitamin C that increase iron absorption

- Fruits: citrus fruits (e.g., oranges, grapefruit) and juices, tomatoes, cantaloupe, kiwi

- Vegetables: leafy greens (e.g., spinach, cabbage), cauliflower, broccoli, Brussels sprouts, green and red peppers

Dietary practices that prevent iron deficiency

- Limit cow’s milk to 2 to 3 cups (500–750 mL) per day

- Limit juice to 1/2 to 3/4 cup (125–175 mL) per day

- Cow’s milk, juice, and water should be offered from an open cup, and baby bottles should be discontinued when the child is 12–15 months of age or preferably earlier

- Ensure iron-rich and vitamin C–containing foods for infants breastfed beyond 6 months

- Do not give tea, which impairs iron absorption

Learning Activities

Technology Note: The second edition of the Human Nutrition Open Educational Resource (OER) textbook features interactive learning activities. These activities are available in the web-based textbook, not downloadable versions (EPUB, Digital PDF, Print_PDF, or Open Document).

Learning activities may be used across various mobile devices, however, for the best user experience it is strongly recommended that users complete these activities using a desktop or laptop computer.

- Polan, E., and Taylor, D., (2003). Journey Across the Life span: Human Development and Health Promotion. F.A. Davis Co. ↵

- U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2020). Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025. https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/sites/default/files/2020-12/Dietary_Guidelines_for_Americans_2020-2025.pdf#page=66 . Accessed July 30, 2025 ↵

- U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2020). Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025. https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/sites/default/files/2020-12/Dietary_Guidelines_for_Americans_2020-2025.pdf#page=66 . Accessed July 30, 2025 ↵

- How Much Should My Child Eat? A Guide to Serving Sizes from Infancy to Preschool. Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. https://www.eatright.org/health/pregnancy/babys-first-foods/how-much-should-my-child-eat-a-guide-to-serving-sizes-from-infancy-to-preschool. Published May 16, 2025. Accessed August 5, 2025. ↵

- U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2020). Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025. https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/sites/default/files/2020-12/Dietary_Guidelines_for_Americans_2020-2025.pdf#page=66 . Accessed July 30, 2025 ↵

- Ellyn Satter’s Division of Responsibility in Feeding. Ellyn Sattter Institute. https://www.ellynsatterinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/ELLYN-SATTER%E2%80%99S-DIVISION-OF-RESPONSIBILITY-IN-FEEDING.pdf. Accessed August 14, 2025. ↵

- Ogden, C., and Carroll, M., (2010). Prevalence of Obesity Among Children and Adolescents: United States, Trends 1963-1965 through 2007-2008. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hestat/obesity_child_07_08/obesity_child_07_08.pdf. Published June 2010. Accessed August 14, 2025. ↵

- Childhood Obesity Facts. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/childhood-obesity-facts/childhood-obesity-facts.html . Accessed August 5, 2025. ↵

- Childhood Obesity Facts. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/childhood-obesity-facts/childhood-obesity-facts.html . Accessed August 5, 2025. ↵

- Decline in Early Childhood Obesity in WIC Families. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://archive.cdc.gov/#/details?=toddler%20obesity%20in%20us&start=0&rows=10&url=https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2019/p1121-decline-childhood-obesity-wic-families.html. Accessed August 5, 2025. ↵

- Tungare, S., and Paranjpe, A.G., (2023). Early Childhood Caries - StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelf. National Library of Medicine. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK535349/#. Accessed August 5, 2025. ↵

- Ervin, R. B., et al., (2012). Consumption of Added Sugar Among U.S. Children and Adolescents, 2005-2008: NCHS Data Brief 87. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db87.pdf. Published March 2012. Accessed August 14, 2025. ↵

- Tungare, S. and Paranjpe, A.G. (2023). Early Childhood Caries - StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelf. National Library of Medicine. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK535349/#. Accessed August 5, 2025. ↵

- Louis A., Kazal J.R., (2002). Prevention of Iron Deficiency in Infants and Toddlers. American Academy of Family Physicians, 66 (7): 1217—25. http://www.aafp.org/afp/2002/1001/p1217.html. Accessed August 5, 2025. ↵

- Baker, R.D., and Greer, F.R., (2010). Diagnosis and Prevention of Iron Deficiency and Iron-Deficiency Anemia in Infants and Young Children (0-3 Years of Age). Pediatrics, 126 (5): 1040-50. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20923825/. Accessed August 5, 2025. ↵

- Parkin, P.C., and Maguire, J.L., (2013). Iron Deficiency in Early Childhood. Canadian Medical Association Journal 185(14):1237-38. https://www.cmaj.ca/content/185/14/1237.Accessed August 5, 2025. ↵

The period of early childhood from birth to 1 year of age.

The major structural and supportive connective tissue of the body.

A period of sexual maturity where rapid growth and physical changes occur.

A fundamental unit of energy, equal to 4.1855 joule; 1000 calories equals 1 kcal.

(Acceptable Macronutrient Distribution Ranges) A range of intakes for carbohydrates, fat, and protein expressed as a percentage of total energy intake for normal healthy individuals.

A person’s weight in kilograms divided by their height in meters squared.

An iron-containing protein found in red blood cells that bind and transports oxygen throughout the body.