Pregnancy

Consuming healthy foods at every phase of life, beginning in the womb, is crucial. Good nutrition is vital for any pregnancy and not only helps an expectant mother remain healthy, but also impacts the development of the fetus and ensures that the baby thrives in infancy and beyond. During pregnancy, a woman’s needs increase for specific nutrients more than for others. If these nutritional needs are not met, infants could suffer from low birth weight (a birth weight less than 5.5 pounds, which is 2,500 grams), among other developmental problems. Therefore, it is crucial to make careful dietary choices.

The Early Days of Pregnancy

For medical purposes, pregnancy is measured from the first day of a woman’s last menstrual period until childbirth and typically lasts about forty weeks. Major changes begin in the earliest days, often weeks before a woman even knows she is pregnant. During this period, adequate nutrition supports cell division, tissue differentiation, and organ development. As each week passes, new milestones are reached. Therefore, women trying to conceive should make proper dietary choices to ensure the delivery of a healthy baby. Fathers-to-be should also consider their eating habits.

Simple steps to increase the chances of producing healthy sperm include maintaining a healthy weight, as increasing body mass index (BMI) is linked with decreasing sperm count and sperm movement. Eating a healthy diet with plenty of fruits and vegetables, which are rich in antioxidants, might help improve sperm. Moderate physical activity can increase levels of powerful antioxidant enzymes, which can help protect sperm. Managing stress is essential for having better sperm production. There are also some things to avoid for father candidates. The most important things to avoid are smoking and alcohol, and exposure to pesticides, lead, and other toxins can affect sperm quantity and quality.[1]

For both men and women, adopting healthy habits also boosts general well-being and makes it possible to meet the demands of parenting.

Folic Acid Supplementation

For women who may get pregnant, folate is really important. Getting enough folic acid before and during pregnancy can prevent major birth defects of her baby’s brain or spine, namely Neural Tube Defects. Folic acid, also known as Vitamin B9 or folate, helps the body make healthy new cells. Everyone needs folic acid. It is crucial to the production of DNA and RNA and the formation of cells. A deficiency can cause megaloblastic anemia, or the development of abnormal red blood cells, in pregnant women. It can also have a profound effect on the unborn baby. Typically, folate intake has the greatest impact during the first eight weeks of pregnancy, when the neural tube closes. NTDs happen in about 3,000 pregnancies each year in the United States. Hispanic women are more likely than non-Hispanic women to have a baby with an NTD. The two most common NTDs are spina bifida and anencephaly. Spina bifida affects about 1,500 babies a year in the United States. Folic acid also supports the spinal cord and its protective coverings. Inadequate folic acid can result in birth defects, such as spina bifida, which is the failure of the spinal column to close.

The name “folate” is derived from the Latin word folium for leaf, and leafy green vegetables such as spinach and kale are excellent sources of it. Foods with folic acid in them include: Leafy green vegetables, fruits, dried beans, peas, and nuts, enriched breads, cereals, and other grain products. The protective effect of periconceptional folic acid supplementation against neural tube defects (NTDs) led to mandatory folic acid fortification in the United States. Since 1998, food manufacturers have been required to add folate to cereals and other grain products. [2] The prevalence of neural tube defects (NTDs) has decreased by 35 percent since folic acid fortification in the United States, which translates to about 1,300 babies born NTD-free annually because of this intervention.[3]

The CDC urges all women of childbearing age, whether planning a pregnancy or not, to get 400 mcg of folic acid daily from fortified foods, supplements, or both, in addition to consuming folate-rich foods from a varied diet. Getting the recommended amount of folic acid is an important way to help prevent these serious birth defects. A pregnancy may happen unexpectedly, or a woman wouldn’t know about the pregnancy until she misses a period, which means she is already 5 weeks pregnant. Therefore, all women of childbearing age need to get 400 micrograms of folate daily before and during pregnancy. If the mother has a previous history of Neural tube Defect babies, the recommended amount is ten times more, 4 mg to take daily for pregnant women.

Weight Gain during Pregnancy

During pregnancy, a mother’s body changes in many ways. One of the most notable and significant changes is weight gain. If a pregnant woman does not gain enough weight, her unborn baby will be at risk. Poor weight gain, especially in the second and third trimesters, could result not only in low birth weight, but also infant mortality and intellectual disabilities. Therefore, a pregnant woman needs to maintain a healthy weight gain. Her weight before pregnancy also has a significant effect. Infant birth weight is one of the best indicators of a baby’s future health. Pregnant women of normal prepregnancy weight should gain between 25 and 35 pounds throughout pregnancy. The precise amount that a mother should gain usually depends on her beginning weight or body mass index (BMI). See Table 12.1 “Body Mass Index and Pregnancy” for the Institute of Medicine (IOM) recommendations.[4] A variety of BMI calculators are available online.

| Prepregnancy BMI | Weight Category | Recommended Weight Gain |

| Below 18.5 | Underweight | 28-40 lbs. |

| 18.5-24.9 | Normal | 25-35 lbs. |

| 25.0-29.9 | Overweight | 15-25 lbs. |

| Above 30.0 | Obese (all classes) | 11-20 lbs. |

A healthy weight gain during pregnancy will help you avoid pregnancy complications such as gestational diabetes, preeclampsia, and cesarean delivery. Starting weight below or above the normal range can lead to different complications. Pregnant women with a prepregnancy BMI below twenty are at a higher risk of a preterm delivery and an underweight infant. Pregnant women with a prepregnancy BMI abcesareanove thirty have an increased risk for a cesarean section during delivery. Therefore, having a BMI in the normal range before pregnancy is optimal.

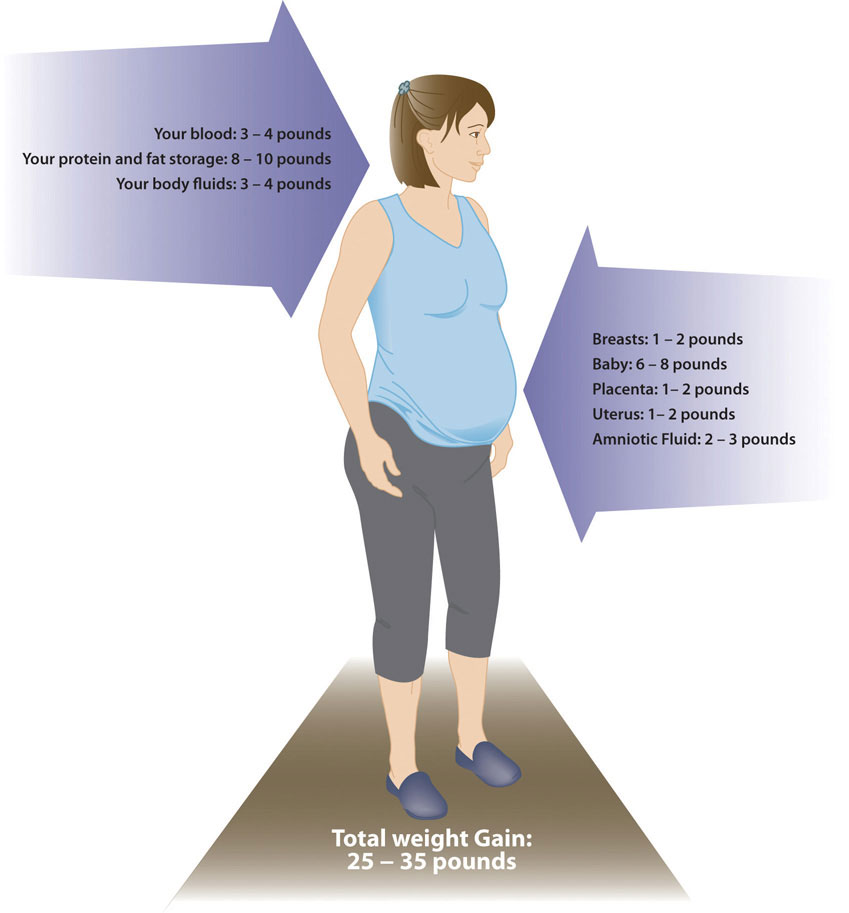

Generally, women gain 2 to 5 pounds in the first trimester. After that, it is best not to gain more than one pound weekly. Some of the new weight is due to the growth of the fetus, while some is due to changes in the mother’s body that support the pregnancy. Weight gain often breaks down in the following manner as shown in Figure 13.2 6 to 8 pounds of fetus, 1 to 2 pounds for the placenta (which supplies nutrients to the fetus and removes waste products), 2 to 3 pounds for the amniotic sac (which contains fluids that surround and cushion the fetus), 1 to 2 pounds in the breasts, 1 to 2 pounds in the uterus, 3 to 4 pounds of maternal blood, 3 to 4 pounds maternal fluids, and 8 to 10 pounds of extra maternal fat stores that will be needed for breastfeeding and delivery.

Weight Gain in Multi-fetal Pregnancy

Weight gain in multiple pregnancy depends on several factors, including height, body type, and pre-pregnancy weight. For twin pregnancy, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) recommends a gestational weight gain of 16.8–24.5 kg (37–54 lb) for women of normal weight, 14.1–22.7 kg (31–50 lb) for overweight women, and 11.3–19.1 kg (25–42 lb) for obese women. The IOM guidelines recognize that data are insufficient to determine the amount of weight women with multifetal (triplet and higher order) gestations should gain. [5] Women carrying triplets are advised to gain 50 to 60 pounds. Currently, there is not enough information on quadruplets and quintuplets to suggest any guidelines. Women carrying twins will only gain 4 to 6 pounds during the first trimester and 1 ½ pounds per week during the second and third trimesters. If you are carrying triplets, you should expect to gain 1 ½ pound per week throughout the entire pregnancy.[6]

In multiple pregnancy, the weight gain recommendation for overweight women is less than that of average women, 31-50 pounds, and for obese women, 25-42 pounds.[7]

On a trimester basis in a woman with normal pre-pregnancy weight:[/footnote]Pregnancy Weight Gain Chart. American Pregnancy Association. https://americanpregnancy.org/healthy-pregnancy/pregnancy-health-wellness/pregnancy-weight-gain/. Accessed July 31, 2025.[/footnote]

- First trimester: 1-4.5 pounds

- Second trimester: 1-2 pounds per week

- Third trimester: 1-2 pounds per week

(Source: University of Hawaii @ Manoa, CC-BY-NC-SA)

The pace of weight gain is also significant. If a woman puts on weight too slowly, her physician may recommend nutritional counseling. If she gains weight too quickly, especially in the third trimester, it may be the result of edema, or swelling due to excess fluid accumulation. Pregnancy complications like pre-eclampsia can be the cause of sudden weight gain. Rapid weight gain may also result from increased calorie consumption or a lack of exercise.

Weight Loss after Pregnancy

Weight loss of approximately 10 to 15 pounds occurs immediately after the delivery of the infant, placenta, and amniotic fluid. Depending on the amount of edema during pregnancy and labor, some persons lose more than 5 pounds in extracellular fluid over the first few postpartum days. The average amount of postpartum fluid loss is 2 liters, with the majority over the first 5 to 7 days after giving birth. Blood loss occurs during birth and postpartum, causing a decrease in intravascular fluid. Normal blood loss during a vaginal birth is approximately 500 mL and up to 1,000 mL for a cesarean birth.[8] The placenta also retains 75 to 400 mL of blood after delivery, depending on the infant’s weight.[9]

Some studies have hypothesized that breastfeeding also helps a new mother lose some of the extra weight.[10] Breastfeeding may lead to greater postpartum weight loss due to increased energy expenditures or hormonal changes.[11]

New mothers who gain a healthy weight and participate in regular physical activity during their pregnancies also have an easier time shedding weight post-pregnancy. However, women who gain more weight than needed for a pregnancy typically retain that excess weight as body fat. If those few pounds increase a new mother’s BMI by a unit or more, that could lead to complications such as hypertension or Type 2 diabetes in future pregnancies or later in life.

Nutritional Requirements

As a mother’s body changes, so do her nutritional needs. Pregnant women must consume more calories and nutrients in the second and third trimesters than other adult women. However, the recommended daily caloric intake can vary depending on activity level and the mother’s normal weight. Also, pregnant women should choose a high-quality, diverse diet, consume fresh foods, and prepare nutrient-rich meals. Steaming is one of the best ways to cook vegetables. Vitamins are destroyed by overcooking, whereas uncooked vegetables and fruits have the highest vitamin content. It is also recommended for pregnant women to take prenatal supplements to ensure adequate intake of the needed micronutrients.[12]

Energy and Macronutrients

During the first trimester, a pregnant woman has the same energy requirements as normal and should consume the same number of calories as usual. However, as the pregnancy progresses, a woman must increase her caloric intake. According to the Institute of Medicine (IOM), pregnant women do not need extra calories during the first trimester but should focus on a nutrient-dense diet. During the second trimester, she should consume an additional 340 calories per day, and during the third trimester, an additional 450 calories per day. These increased energy needs are partly due to a rise in metabolism during pregnancy. A woman can easily meet these needs by consuming more nutrient-dense foods.[13]

A pregnant woman of normal weight, who gets less than 30 minutes of exercise a week, should strive for a caloric intake of:

- 1,800 during the first trimester

- 2,200 during the second trimester

- 2,400 during the third trimester

These calories should be attained by eating a diet of grains, dairy, protein, fruits/vegetables, and healthy fats and oils. Limiting processed foods, sugars, and extra fats can help you attain your goals.[/footnote]Pregnancy Weight Gain Chart. American Pregnancy Association. https://americanpregnancy.org/healthy-pregnancy/pregnancy-health-wellness/pregnancy-weight-gain/. Accessed July 31, 2025.[/footnote]

The recommended daily allowance, or RDA, of carbohydrates during pregnancy is about 175 to 265 grams daily to fuel fetal brain development. The best food sources for pregnant women include whole-grain breads and cereals, brown rice, root vegetables, legumes, and fruits. These and other unrefined carbohydrates provide nutrients, phytochemicals, antioxidants, and the extra 3 mg/day of fiber recommended during pregnancy. These foods also help build the placenta and supply energy for the unborn baby’s growth.

During pregnancy, extra protein is needed to synthesize new maternal and fetal tissues. Protein builds muscle and other tissues, enzymes, antibodies, and hormones in both the mother and the unborn baby. Additional protein also supports increased blood volume and the production of amniotic fluid. The RDA of protein during pregnancy is 71 grams per day, 25 grams above the standard recommendation. This increase reflects a change to 1.1g of protein/kg/day during pregnancy from 0.8g of protein/kg/day for non-pregnant states.[14] Protein should be derived from healthy sources, such as lean red meat, poultry, legumes, nuts, seeds, eggs, and fish. Low-fat milk and other dairy products also provide protein, along with calcium and other nutrients.

Apart from following standard dietary guidelines, there are no specific recommendations for fats in pregnancy. Total fat intake should comprise 20-35% of daily calories, similar to non-pregnant women.[15] Although this is the case, it is recommended to increase the amount of essential fatty acids, linoleic acid, and ∝linolenic acid, because they are incorporated into the placenta and fetal tissues. Fats should make up 25 to 35 percent of daily calories, which should come from healthy fats, such as avocados and salmon. Pregnant women are not recommended to be on a very low-fat diet, since it would be hard to meet the needs of essential fatty acids and fat-soluble vitamins. Fatty acids are important during pregnancy because they support the baby’s brain and eye development.

Fluids

Fluid intake must also be monitored. According to the IOM, pregnant women should drink 2.3 liters (about 10 cups) of daily liquids to provide enough fluid for blood production. It is also important to drink liquids during and after physical activity or when it is hot and humid outside, to replace fluids lost to perspiration. The combination of a high-fiber diet and lots of liquids also helps to prevent constipation, a common complaint during pregnancy.[16]

Vitamins and Minerals

The daily requirements for nonpregnant women change with the onset of pregnancy. Taking a daily prenatal supplement or multivitamin helps to meet many nutritional needs. However, most of these requirements should be fulfilled with a healthy diet. The following table compares the normal levels of required vitamins[17] and minerals[18] to those needed during pregnancy. For pregnant women, the RDA of nearly all vitamins and minerals increases.[19]

| Nutrient | Nonpregnant Women | Pregnant Women |

|---|---|---|

| Vitamin A (mcg) | 700.0 | 770.0 |

| Vitamin B6 (mg) | 1.5 | 1.9 |

| Vitamin B12 (mcg) | 2.4 | 2.6 |

| Vitamin C (mg) | 75 | 85 |

| Vitamin D (mcg) | 15 | 15 |

| Vitamin E (mg) | 15 | 15 |

| Calcium (mg) | 1,000.0 | 1,000.0 |

| Folate (mcg) | 400 | 600 |

| Iron (mg) | 18 | 27 |

| Magnesium (mg) | 320 | 360 |

| Niacin(B3) (mg) | 14 | 18 |

| Phosphorus | 700 | 700 |

| Riboflavin (B2) (mg) | 1.1 | 1.4 |

| Thiamine (B1) (mg) | 1.1 | 1.4 |

| Zinc (mg) | 8 | 11 |

The micronutrients involved with building the skeleton—vitamin D, calcium, phosphorus, and magnesium—are crucial during pregnancy to support fetal bone development. Although the levels are the same as those for nonpregnant women, many women do not typically consume adequate amounts and should make an extra effort to meet those needs. Many of these nutrient requirements are higher yet for pregnant mothers who are in their teen years due to higher needs for their own growth in addition to the growth of the fetus.

There is an increased need for all B vitamins during pregnancy. Adequate vitamin B6 supports the metabolism of amino acids, while more vitamin B12 is needed for the synthesis of red blood cells and DNA. Also, remember that folate needs increase during pregnancy to 600 micrograms per day to prevent neural tube defects. This micronutrient is crucial for fetal development because it also helps produce the extra blood a woman’s body requires during pregnancy.

Additional zinc is crucial for cell development and protein synthesis. The need for vitamin A also increases, and extra iron intake is important because of the increase in blood supply during pregnancy and to support the fetus and placenta. Iron is the one micronutrient that is almost impossible to obtain in adequate amounts from food sources only. Therefore, even if a pregnant woman consumes a healthy diet, there is still a need to take an iron supplement, in the form of ferrous salts.

For most other minerals, recommended intakes are similar to those for nonpregnant women, although it is crucial for pregnant women to make sure to meet the RDAs to reduce the risk of birth defects. In addition, pregnant mothers should avoid exceeding the Upper Limit recommendations. Taking megadose supplements can lead to excessive amounts of certain micronutrients, such as vitamin A and zinc, which may produce toxic effects that can also result in birth defects.

Guide to Eating during Pregnancy

While pregnant women have an increased need for energy, vitamins, and minerals, energy increases are proportionally less than other macronutrient and micronutrient increases. So, nutrient-dense foods, which are higher in proportion of macronutrients and micronutrients relative to calories, are essential to a healthy diet. Nutrient-Dense Foods and Beverages provide vitamins, minerals, and other health-promoting components and have little added sugars, saturated fat, and sodium. Vegetables, fruits, whole grains, seafood, eggs, beans, peas, and lentils, unsalted nuts and seeds, fat-free and low-fat dairy products, and lean meats and poultry—when prepared with no or little added Sugars, saturated fat, and sodium—are nutrient-dense foods.[20]

Pregnant women should be able to meet almost all of their increased needs via a healthy diet. However, expectant mothers should take a prenatal supplement to ensure an adequate intake of iron and folate. Here are some additional dietary guidelines for pregnant women.[21]:

Iron Needs During Pregnancy and Lactation

Iron is a key nutrient during pregnancy that supports fetal development. Iron deficiency affects about 1 in 10 pregnant women and 1 in 4 women during their third trimester. Heme iron, which is found in animal source foods (e.g., lean meats, poultry, and some seafood), is more readily absorbed by the body than the non-heme iron found in plant source foods (e.g., beans, peas, lentils, and dark-green vegetables). Additional iron sources include foods enriched or fortified with iron, such as many whole-wheat breads and ready-to-eat cereals. Iron absorption from non-heme sources is enhanced by consuming them along with vitamin C-rich foods. To enhance iron absorption, include vitamin C-rich foods, such as orange juice, broccoli, or strawberries. Women who are pregnant or who are planning to become pregnant are advised to take a supplement containing iron when recommended by an obstetrician or other healthcare provider. More than half of women continue to use prenatal supplements during lactation. Most prenatal supplements are designed to meet the higher iron needs of pregnancy. Depending on various factors—such as when menstruation returns—prenatal supplements may exceed the iron needs of women who are lactating.[22]

Iodine During Pregnancy

Iodine needs increase substantially during pregnancy and lactation. You need extra iodine during pregnancy for fetal brain development, healthy bone growth, and nerve development. Adequate iodine intake during pregnancy is also important for the neurocognitive development of the fetus. The recommended amount of iodine for pregnant women is 220 micrograms each day, and for breastfeeding women is 290 micrograms. The upper tolerable limit, or the most that can be safely consumed, is 1,100 micrograms. If a pregnant woman has a thyroid condition, she must consult her doctor or midwife before taking an iodine supplement. Excess amounts of iodine can also lead to an overactive thyroid, a condition that’s also called iodine-induced hyperthyroidism (IHH). A woman with hyperthyroidism must not use iodine supplements.[23]

Although women of reproductive age generally have adequate iodine intake, some women, particularly those who do not regularly consume dairy products, eggs, seafood, or use iodized table salt, may not consume enough iodine to meet increased needs during pregnancy and lactation. Women should ensure that any table salt used in cooking or added to food at the table is iodized. Additionally, pregnant or lactating women may need a supplement containing iodine to achieve adequate intake. Many prenatal supplements do not contain iodine. Thus, it is essential to read the label. [24]

Choline Needs During Pregnancy

Choline needs also increase during pregnancy and lactation. Adequate choline intake during these life stages helps replenish maternal stores and support the growth and development of the child’s brain and spinal cord. Most women do not meet the recommended intakes of choline during pregnancy and lactation. Women are encouraged to consume various choline-containing foods during these life stages. Choline can be found throughout many food groups and subgroups. Meeting recommended intakes for the dairy and protein food groups—with eggs, meats, and some seafood being notable sources—as well as the beans, peas, and lentils subgroup, can help meet choline needs. Many prenatal supplements do not contain choline or only small amounts inadequate to meet recommendations.[25]

Foods to Avoid

A number of substances can harm a growing fetus. Therefore, women need to avoid them throughout a pregnancy. Some are so detrimental that a woman should avoid them even if she suspects that she might be pregnant.

Alcoholic beverages

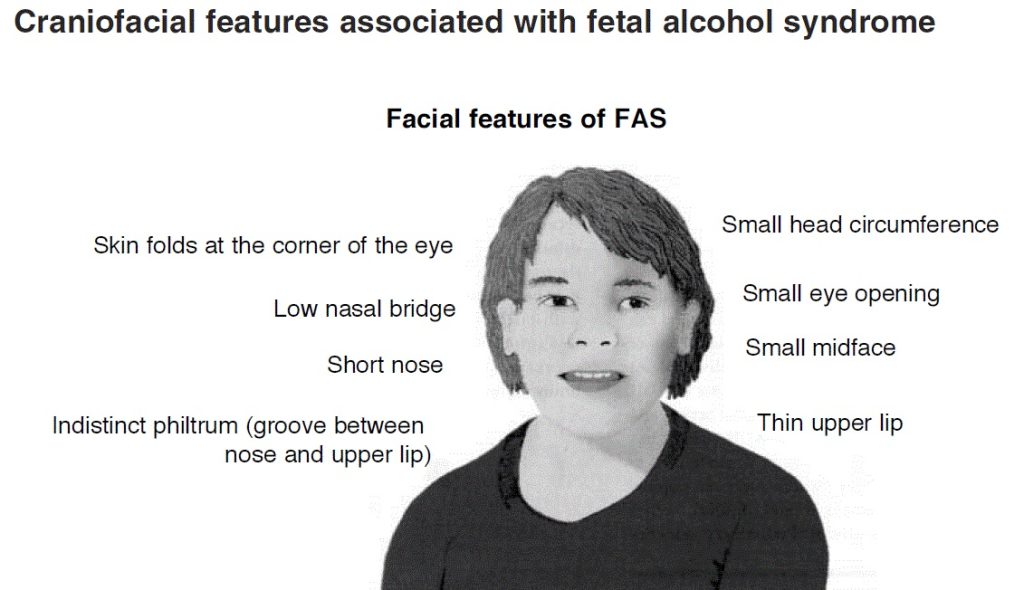

Women who are or who may be pregnant should not drink alcohol. However, consumption of alcohol during pregnancy continues to be of concern in the United States. Among women who are pregnant, about 1 in 10 reported consuming alcohol during the past month, with an average intake of 2 or more drink equivalents on days alcohol is consumed. It is not safe for women to drink any type or amount of alcohol during pregnancy. Women who drink alcohol and become pregnant should stop drinking immediately and not drink at all. Alcohol can harm the baby at any time during pregnancy, even during the first or second month when a woman may not know she is pregnant. Not drinking alcohol is also the safest option for women who are lactating. Generally, moderate consumption of alcoholic beverages by a woman who is lactating (up to 1 standard drink per day) is not known to be harmful to the infant, especially if the woman waits at least 2 hours after a single drink before nursing or expressing breast milk.[26] Consumption of alcoholic beverages results in a range of abnormalities that fall under the umbrella of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. They include learning and attention deficits, heart defects, and abnormal facial features (See Figure 13.6). Alcohol enters the unborn baby via the umbilical cord and can slow fetal growth, damage the brain, or even result in miscarriage. The effects of alcohol are most severe in the first trimester, when the organs are developing. There is no safe amount of alcohol that a pregnant woman can consume. Although pregnant women in the past may have participated in behavior that was not known to be risky at the time, such as drinking alcohol or smoking cigarettes, today we see that it is best to avoid those substances altogether to protect the health of the unborn baby.

(Source: Wikimedia Commons, National Institutes of Health, Public Domain)

Caffeine

Pregnant women should also limit caffeine intake, which is found in coffee and tea, colas, cocoa, chocolate, and some over-the-counter painkillers. Some studies suggest that very high amounts of caffeine have been linked to babies born with low birth weights. The American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology released a report, which found that women who consume 200 milligrams or more of caffeine a day (which is the amount in 10 ounces of coffee or 25 ounces of tea) increase the risk of miscarriage[27]. Many women consume caffeine during pregnancy or lactation. Most of the caffeine intake in the United States comes from coffee, tea, and soda. Caffeinated beverages vary widely in their caffeine content. Caffeine passes from the mother to the infant in small amounts through breast milk. Usually, it does not adversely affect the infant when the mother consumes low to moderate amounts (about 300 milligrams or less per day, which is about 2 to 3 cups of coffee). Women who could be or who are pregnant should consult their healthcare providers for advice concerning caffeine consumption.[28]

Women who are pregnant or who are trying to become pregnant and those who are breastfeeding should talk with their doctors about limiting caffeine use to less than 200 mg daily.[29] Consuming large quantities of caffeine affects the pregnant mother as well, leading to irritability, anxiety, and insomnia. Most experts agree that small amounts of caffeine each day are safe (about one 8-ounce cup of coffee a day or less).[30] However, that amount should not be exceeded.

Foodborne Illness

Women who are pregnant and their unborn children are more susceptible than the general population to the effects of foodborne illnesses. For both mother and child, foodborne illness can cause major health problems.

Listeria Monocytogenes

The foodborne illness caused by the bacteria Listeria monocytogenes can cause spontaneous abortion and fetal or newborn meningitis. According to the CDC, pregnant women are twenty times more likely to become infected with this disease, which is known as listeriosis, than nonpregnant, healthy adults. Symptoms include headaches, muscle aches, nausea, vomiting, and fever. If the infection spreads to the nervous system, it can result in a stiff neck, convulsions, or a feeling of disorientation.[31]

Listeria monocytogenes is a type of bacteria that is found in water and soil. Vegetables can become contaminated from the soil, and animals can also be carriers. Foods more likely to contain bacteria that should be avoided include Listeria, which is found in uncooked meats, uncooked vegetables, unpasteurized milk, foods made from unpasteurized milk, and processed foods. Listeria is killed by pasteurization and cooking. There is a chance that contamination may occur in ready-to-eat foods such as hot dogs and deli meats because contamination may occur after cooking and before packaging. To avoid consuming contaminated foods, women who are pregnant or breastfeeding should take the following measures:footnote]Listeria and Pregnancy. American Pregnancy Association. http://www.americanpregnancy.org/pregnancycomplications/listeria.html. Accessed February 28, 2025.[/footnote]

Practice safe food handling:

- Thoroughly rinse all fruits and vegetables before eating them

- Keep everything clean, including your hands and preparation surfaces

- Keep cooked and ready-to-eat food separate from raw meat, poultry, and seafood

- Store food at 40° F (4° C) or below in the refrigerator and at 0° F (−18° C) in the freezer

- Refrigerate perishables, prepared food, or leftovers within two hours of preparation or eating

- Clean the refrigerator regularly and wipe up any spills right away

- Check the expiration dates of stored food once per week

- Cook foods at proper temperatures (use food thermometers) and reheat all foods until they are steaming hot (or 160°F)

- Cook hot dogs, cold cuts (e.g., deli meats/luncheon meat), and smoked seafood to 160°F before consuming

Proper Temperatures for Cooking Foods:

- Chicken: 165-180°F

- Egg Dishes: 160°F

- Ground Meat: 160-165°F

- Beef, Medium well: 160°F

- Beef, Well Done: 170°F (not recommended to eat any meat cooked rare)

- Pork: 160-170°F

- Ham (raw): 160°F

- Ham (precooked): 140°F

It is always important to avoid consuming contaminated food to prevent food poisoning. This is especially true during pregnancy. Heavy metal contaminants, particularly mercury, lead, and cadmium, pose risks to pregnant mothers. As a result, vegetables should be washed thoroughly or have their skins removed to avoid consuming heavy metals. Maintaining good iron status helps women not to absorb these heavy metals, so it provides an additional level of protection.

Seafood and Methylmercury Exposure

Seafood intake during pregnancy is recommended, as it is associated with favorable measures of cognitive development in young children. Pregnant or lactating women should consume at least eight and up to 12 ounces of a variety of seafood per week, from choices lower in methylmercury. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) provide joint advice regarding seafood consumption to limit methylmercury exposure for women who might become or who are pregnant or lactating. Methylmercury can be harmful to the brain and nervous system if a person is exposed to too much of it over time; this is particularly important during pregnancy because eating too much of it can have negative effects on the developing fetus.

Expectant mothers can eat cooked shellfish such as shrimp, farm-raised fish such as salmon, and a maximum of 6 ounces of albacore (white) tuna. Canned light tuna is preferred over canned white albacore tuna because it has lower mercury levels. Pregnant women need to avoid fish with very high methylmercury levels, such as fish high in mercury, such as swordfish and shark).shark, swordfish, tilefish, and king mackerel. Pregnant women should also avoid consuming raw fish and shellfish to prevent foodborne illness. The Environmental Defense Fund eco-rates fish to provide guidelines to consumers about the safest and most environmentally friendly choices. You can find ratings for fish and seafood at the EDF web site (opens in a new window)

Physical Activity during Pregnancy

Physical activity during pregnancy can benefit both the mother and the baby. Physical activity increases or maintains cardiorespiratory fitness and reduces the risk of excessive weight gain and gestational diabetes. For many benefits, healthy women without contraindications should do at least 150 minutes of moderate intensity aerobic activity a week, as they are able. Women who habitually did vigorous-intensity activity or a lot of aerobic or muscle-strengthening physical activity before pregnancy can continue to do so during pregnancy. Women can consult their healthcare provider about whether or how to adjust their physical activity during pregnancy[32].

Regular moderate intensity exercise, about thirty minutes daily most days a week, keeps the heart and lungs healthy. It also helps to improve sleep and boost mood and energy levels. In addition, women who exercise during pregnancy report fewer discomforts and may easily lose excess weight after childbirth. Brisk walking, swimming, or an aerobics class geared toward expectant mothers are all great ways to exercise during pregnancy. Healthy women who already participate in vigorous activities before pregnancy, such as running, can continue during pregnancy, provided they discuss an exercise plan with their physicians.

However, pregnant women should avoid pastimes that could cause injury, such as soccer, football, and other contact sports, or activities that could lead to falls, such as horseback riding and downhill skiing. It may be best for pregnant women not to participate in certain sports, such as tennis, that require you to jump or change direction quickly. Scuba diving should also be avoided because it might result in the fetus developing decompression sickness. This potentially fatal condition results from a rapid decrease in pressure when a diver ascends too quickly.[33]

Food Cravings and Aversions

Food aversions and cravings do not have a major impact unless food choices are minimal. The most common food aversions are milk, meats, pork, and liver. For most women, indulging in the occasional craving, such as the desire for pickles and ice cream, is not harmful. However, a medical disorder known as pica occurs during pregnancy more often than in nonpregnant women. Pica is the willingness to consume foods with little or no nutritive value, such as dirt, clay, laundry starch, and large quantities of ice or freezer frost. In some places, this is a culturally accepted practice. However, it can be harmful if these substances replace nutritious foods or contain toxins. Pica is associated with iron deficiency, sometimes even in the absence of anemia, and iron tends to cure the pica behavior.

Complications during Pregnancy

Physical and mental conditions that can lead to complications may start before, during, or after pregnancy. Living a healthy lifestyle and getting health care before, during, and after pregnancy can lower your risk of pregnancy complications. For example, eat healthy, stay at a healthy weight, avoid tobacco products, take care of mental health, and avoid any alcohol use. Preconception health care can also help women be healthy before pregnancy.[34]

Expectant mothers may face different complications during their pregnancy. They include certain medical conditions that could significantly impact a pregnancy if left untreated, such as gestational hypertension and gestational diabetes, which have diet and nutrition implications.

Gestational Hypertension

Gestational hypertension is a condition of high blood pressure during the second half of pregnancy. First-time mothers are at greater risk, along with women who have mothers or sisters who have gestational hypertension, women carrying multiple fetuses, women with a prior history of high blood pressure or kidney disease, and women who are overweight or who have obesity when they become pregnant. Hypertension can prevent the placenta from getting enough blood, resulting in the baby getting less oxygen and nutrients. This can result in low birth weight, although most women with gestational hypertension can still deliver a healthy baby if the condition is detected and treated early.

Some risk factors, such as diet, can be controlled, while others cannot, such as family history. If left untreated, gestational hypertension can lead to a serious complication called preeclampsia and eclampsia, which is sometimes referred to as toxemia of pregnancy. Eclampsia, a rare condition in which a pregnant or postpartum woman suddenly experiences seizures, is a medical emergency. It is a serious complication of pregnancy that can lead to injury or death of the pregnant woman and/or baby. Preeclampsia is marked by elevated blood pressure and protein in the urine and is associated with swelling. To prevent preeclampsia, the WHO recommends increasing calcium intake for women consuming diets low in that micronutrient, administering a low aspirin dosage (75 milligrams), and increasing prenatal checkups. The WHO does not recommend restricting dietary salt intake during pregnancy to prevent the development of pre-eclampsia and its complications.[35]

Diabetes

Diabetes is a disease that affects how your body turns food into energy. There are three main types of diabetes: type 1, type 2, and gestational diabetes. For pregnant women with preexisting diabetes, high blood sugar around the time of conception increases the risk of health problems. These include birth defects, stillbirth, and preterm birth. Among women with any type of diabetes, high blood sugar throughout pregnancy can increase the risk of complications, such as preeclampsia.

Gestational diabetes or uncontrolled blood glucose levels also can cause large for gestational age babies and macrosomia that can also interfere with prolonged labor, cephalopelvic disproportion, and increased cesarean delivery rate.

About 4 percent of pregnant women suffer from a condition known as gestational diabetes, which is abnormal glucose tolerance during pregnancy. The body becomes resistant to the hormone insulin, which enables cells to transport glucose from the blood. Gestational diabetes is usually diagnosed around twenty-four to twenty-six weeks, although the condition can develop later in a pregnancy. Signs and symptoms of this disease include extreme hunger, thirst, or fatigue. If blood sugar levels are not properly monitored and treated, the baby might gain too much weight and require a cesarean delivery. To manage your diabetes, monitor blood sugar levels, follow a good nutrition plan developed with your provider or dietitian, be physically active, and take medications as directed. Managing diabetes is important for having a healthy pregnancy. Diet and regular physical activity can help manage this condition. Some patients who suffer from gestational diabetes may also require oral antidiabetic medication or daily insulin injections to boost glucose absorption from the bloodstream and promote the storage of glucose in the form of glycogen in liver and muscle cells. Gestational diabetes usually resolves after childbirth, although women who experience this condition are more likely to develop Type 2 diabetes later in life, particularly if they are overweight.[36]

CDC’s Hear Her® campaign

The Hear Her campaign supports the CDC’s efforts to prevent pregnancy-related complications and deaths by sharing potentially life-saving messages about urgent maternal warning signs. If you have an urgent maternal warning sign during or after pregnancy, get medical care immediately.[37]

Learning Activities

Technology Note: The second edition of the Human Nutrition Open Educational Resource (OER) textbook features interactive learning activities. These activities are available in the web-based textbook and are not in downloadable versions (EPUB, Digital PDF, Print_PDF, or Open Document).

Learning activities may be used across various mobile devices; however, for the best user experience, it is strongly recommended that users complete these activities using a desktop or laptop computer.

- Healthy Sperm: Improving your fertility. Mayo Clinic. https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/getting-pregnant/in-depth/fertility/art-20047584. Accessed August 1, 2025. ↵

- Folic Acid: MedlinePlus. National Library of Medicine. https://medlineplus.gov/folicacid.html. Accessed August 1, 2025 ↵

- Updated Estimates of Neural Tube Defect Prevalence at Birth Before and After Mandatory Folic Acid Fortification — United States, 1995–2011. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://archive.cdc.gov/www_cdc_gov/media/mmwrnews/2015/0115.html. Accessed August 1, 2025. ↵

- Weight Gain During Pregnancy: Reexamining the Guidelines. Institute of Medicine of the National Academies. https://nap.nationalacademies.org/resource/12584/Report-Brief---Weight-Gain-During-Pregnancy.pdf. Accessed July 31, 2025. ↵

- Committee Opinion - Weight Gain During Pregnancy. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2013/01/weight-gain-during-pregnancy. Accessed July 31, 2025. ↵

- Weight Gain With Twins. American Pregnancy Association. https://americanpregnancy.org/healthy-pregnancy/multiples/weight-gain-with-multiples/. Accessed on July 31, 2025. ↵

- Lal, A.K. and Kominiarek, M.A. (2015). Weight Gain in Twin gestations: Are the Institute of Medicine Guidelines Optimal for Neonatal Outcomes?. Journal of Perinatolology, 35 (6) :405-10. https://www.nature.com/articles/jp2014237. Accessed August 14, 2025. ↵

- Postpartum Hemorrhage. Children's Hospital of Philadelphia. https://www.chop.edu/conditions-diseases/postpartum-hemorrhage#:~:text=The%20average%20amount%20of%20blood,ml%20(or%20one%20quart).. Accessed August 1, 2025. ↵

- Martin, et al., (2022). Maternal Newborn Nursing: Chapter 20 Postpartum Care.https://med.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Nursing/Maternal-Newborn_Nursing_(OpenStax)/20%3A_Postpartum_Care/20.02%3A_Physiologic_Changes_During_the_Postpartum_Period. Accessed August 1, 2025. ↵

- Stueb,e A.M. and Rich-Edwards, J.W., (2009). The Reset Hypothesis: Lactation and Maternal Metabolism. American Journal of Perinatology, 26 (1): 81–88. ↵

- Jarlenski, M.P., et al., (2014) . Effects of Breastfeeding on Postpartum Weight Loss Among U.S. Women. Preventive Medicine, 69: 146-50. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0091743514003600?via%3Dihub. Accessed August 1, 2025. ↵

- U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2020). Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025. https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/sites/default/files/2020-12/Dietary_Guidelines_for_Americans_2020-2025.pdf. Accessed July 30, 2025 ↵

- Nutrition During Pregnancy. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. https://www.acog.org/womens-health/faqs/nutrition-during-pregnancy2025. Accessed August 4, 2025. ↵

- Kominiarek, M.A. and Rajan, P., (2016). Nutrition Recommendations in Pregnancy and Lactation. Medical Clinics of North America, 100 (6): 1199-1215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcna.2016.06.004. Accessed August 1, 2025. ↵

- Kominiarek, M.A. and Rajan, P., (2016). Nutrition Recommendations in Pregnancy and Lactation. Medical Clinics of North America, 100 (6): 1199-1215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcna.2016.06.004. Accessed August 1, 2025. ↵

- Pregnancy: Body Changes and Discomforts. US Department of Health and Human Services, Office on Women’s Health. https://womenshealth.gov/pregnancy/youre-pregnant-now-what/body-changes-and-discomforts. Accessed August 1, 2025. ↵

- Dietary Reference Intakes (DRIs): Recommended Dietary Allowances and Adequate Intakes, Vitamins.Food and Nutrition Board, Institute of Medicine, National Academies. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK56068/table/summarytables.t2/?report=objectonly. Accessed August 1, 2025 ↵

- Dietary Reference Intakes (DRIs): Recommended Dietary Allowances and Adequate Intakes, Elements. Food and Nutrition Board, Institute of Medicine, National Academies. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK545442/table/appJ_tab3/?report=objectonly. Accessed August 1, 2025. ↵

- Nutrition during Pregnancy: Part I: Weight Gain, Part II: Nutrient Supplements. Institute of Medicine. http://iom.edu/Reports/1990/Nutrition-During-Pregnancy-Part-I-Weight-Gain-Part-II-Nutrient-Supplements.aspx. Published January 1, 1990. Accessed August 1, 2025. ↵

- U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2020). Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025. https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/sites/default/files/2020-12/Dietary_Guidelines_for_Americans_2020-2025.pdf#page=66 . Accessed July 30, 2025 ↵

- Staying Healthy and Safe. US Department of Health and Human Services, Office on Women’s Health. https://www.womenshealth.gov/pregnancy/youre-pregnant-now-what/staying-healthy-and-safe. Accessed August 1, 2025. ↵

- U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2020). Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025. https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/sites/default/files/2020-12/Dietary_Guidelines_for_Americans_2020-2025.pdf#page=66 . Accessed July 30, 2025 ↵

- Iodine in Pregnancy and Lactation. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/tools/elena/bbc/iodine-pregnancy . Accessed August 1, 2025 ↵

- U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2020). Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025. https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/sites/default/files/2020-12/Dietary_Guidelines_for_Americans_2020-2025.pdf. Accessed July 30, 2025 ↵

- U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2020). Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025. https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/sites/default/files/2020-12/Dietary_Guidelines_for_Americans_2020-2025.pdf#page=66 . Accessed July 30, 2025 ↵

- U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2020). Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025. https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/sites/default/files/2020-12/Dietary_Guidelines_for_Americans_2020-2025.pdf#page=66 . Accessed July 30, 2025 ↵

- Weng, X., Odouli, R., Li, D.K., (2008). Maternal Caffeine Consumption During Pregnancy and the Risk of Miscarriage: A Prospective Cohort Study. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology, 198 (3): 279.e1-279.e8. https://www.ajog.org/article/S0002-9378(07)02025-X/fulltext. Accessed August 14, 2025. ↵

- U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2020). Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025. https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/sites/default/files/2020-12/Dietary_Guidelines_for_Americans_2020-2025.pdf#page=66 . Accessed July 30, 2025 ↵

- Caffeine: How Much Is Too Much? Mayo Clinic. https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/nutrition-and-healthy-eating/in-depth/caffeine/art-20045678#:~:text=Up%20to%20400%20milligrams%20(mg,widely%2C%20especially%20among%20energy%20drinks. . Accessed August 1, 2025. ↵

- American Medical Association. (2008). Complete Guide to Prevention and Wellness. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 495. ↵

- Listeria and Pregnancy. American Pregnancy Association. http://www.americanpregnancy.org/pregnancycomplications/listeria.html. Accessed February 28, 2025. ↵

- U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2020). Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025. https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/sites/default/files/2020-12/Dietary_Guidelines_for_Americans_2020-2025.pdf. Accessed July 30, 2025 ↵

- Reid, R. L., and Lorenzo, M., (2018). SCUBA Diving in Pregnancy. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada, 40 (11): 1490–1496. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jogc.2017.11.024. Accessed August 1, 2025. ↵

- Pregnancy Complications: Maternal Infant Health. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/maternal-infant-health/pregnancy-complications/index.html. Accessed August 1, 2025. ↵

- WHO Recommendations for Prevention and Treatment of Pre-eclampsia and Eclampsia. World Health Organization. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/44703/9789241548335_eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Published 2011. Accessed August 5, 2025. ↵

- Noctor, E., and Dunne, F. P., (2015). Type 2 diabetes after gestational diabetes: The influence of changing diagnostic criteria. World Journal of Diabetes, 6 (2): 234–244. https://doi.org/10.4239/wjd.v6.i2.234. ↵

- Signs and Symptoms of Urgent Maternal Warning Signs: Hear Her Campaign. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/hearher/maternal-warning-signs/index.html. Accessed August 1, 2025. ↵

The unborn developing human from the ninth week after conception to birth.

The period of early childhood from birth to 1 year of age.

A birth weight less than 2.5 kg or 5.5 lbs.

NTDs are serious birth defects of the brain or spine.

The term used to describe each 3 month period of a pregnancy.

A person’s weight in kilograms divided by their height in meters squared.

An infant that is born before the 37 weeks of gestation.

C-section, or cesarean birth is the surgical delivery of a baby through a cut (incision) made in the birth parent's abdomen and uterus.

The organ that anchors the developing fetus to the uterus that secretes hormones, transfers nutrients and oxygen from the mother’s blood to the fetus and removes metabolic wastes.

The accumulation of fluid within tissues, making them soft and spongy with a bloated appearance.

Pre-eclampsia is a multi-system disorder specific to pregnancy, characterized by the new onset of high blood pressure and often a significant amount of protein in the urine or by the new onset of high blood pressure along with significant end-organ damage, with or without the proteinuria.

Abnormally high blood pressure.

The internal structure composed of bone or cartilage that provides structure and support to organs and tissues.

A range of physical, behavioral, functional, or mental impairments or disorders that are linked to prenatal alcohol exposure.

An illness caused by the consumption of an contaminated food.

the species of pathogenic bacteria that causes the infection listeriosis.

An abnormal craving for and ingestion of nonfood substances that have little or no nutritional value during pregnancy.

any one of a group of diseases that affect how the body uses blood sugar (glucose).

A condition characterized as elevated blood pressure, a rapid increase in weight, protein in the urine and edema known as toxemia.

High blood glucose levels that develops during pregnancy.

Large for gestational age means that a fetus or infant is larger or more developed than normal for the baby's gestational age. G

Macrosomia refers to a baby who is born much larger than average for their gestational age. It is variably defined as a birth weight over 4000g, over 4500g, or above the 90th centile of weight for gestation. Babies with macrosomia weigh over 8 pounds, 13 ounces.