Childhood

We can divide childhood into three stages: early, middle and late childhood. Early childhood follows the infancy stage and begins with the toddler stage, when the child begins speaking or taking steps independently. While the toddler stage ends around age 3 when the child becomes less dependent on parental assistance for basic needs, early childhood continues approximately until the age of 5 or 6. Middle childhood begins at around age 7 and ends at around age 9 or 10. In this middle period, children develop socially and mentally. They are at a stage where they make new friends and gain new skills, which will enable them to become more independent and enhance their individuality. Late childhood or preadolescence is a stage of human development following early childhood and preceding adolescence. Preadolescence is commonly defined as ages 9–12, ending with the major onset of puberty, with markers such as menarche, spermarche, and the peak of height velocity occurring.

Nutritional Needs

Nutritional needs change as children leave the toddler years. From ages four to eight, school-aged children grow consistently, but at a slower rate than infants and toddlers. They also experience the loss of deciduous, or “baby,” teeth and the arrival of permanent teeth, which typically begins at age six or seven. As new teeth come in, many children have some malocclusion, or malposition, of their teeth, which can affect their ability to chew food. Other changes that affect nutrition include the influence of peers on dietary choices and the kinds of foods offered by schools and after-school programs, which can make up a sizable part of a child’s diet. Food-related problems for young children can include tooth decay, food sensitivities, and malnourishment. Also, excessive weight gain early in life can lead to obesity into adolescence and adulthood.

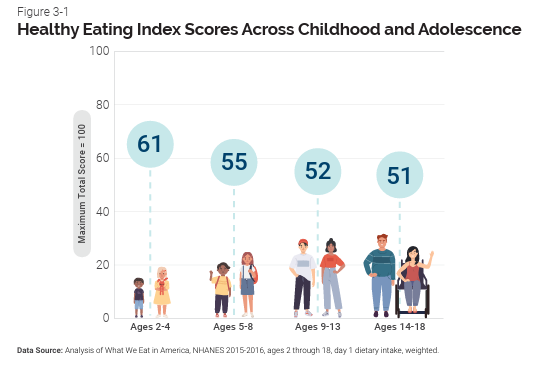

At this life stage, a healthy diet facilitates physical and mental development and helps to maintain health and wellness. School-aged children experience steady, consistent growth, with an average growth rate of 2–3 inches (5–7 centimeters) in height and 4.5–6.5 pounds (2–3 kilograms) in weight per year. In addition, the rate of growth for the extremities is faster than for the trunk, which results in more adult-like proportions. Long-bone growth stretches muscles and ligaments, which results in many children experiencing “growing pains” at night, in particular.[1] A healthy dietary pattern for children and adolescents with daily and weekly amounts of key foods is available in the Dietary Guidelines for Americans (link opens in a new window).

(Source: USDA, Public Domain)

Energy

Children’s energy needs vary, depending on their growth and level of physical activity. Energy requirements also vary according to gender. Girls ages four to eight require 1,200 to 1,800 calories a day, while boys need 1,200 to 2,000 calories daily, and, depending on their activity level, maybe more. Also, recommended intakes of macronutrients and most micronutrients are higher relative to body size, compared with nutrient needs during adulthood. Therefore, children should be provided nutrient-dense food at meal- and snack-time. However, it is important not to overfeed children, as this can lead to childhood obesity, which is discussed in the next section. Parents and other caregivers can turn to the MyPlate website (opens in a new window) for guidance.

Macronutrients

For carbohydrates, the Acceptable Macronutrient Distribution Range (AMDR) is 45–65 percent of daily calories (which is a recommended daily allowance of 135–195 grams for 1,200 daily calories). Carbohydrates high in fiber should make up the bulk of intake. The AMDR for protein is 10–30 percent of daily calories (30–90 grams for 1,200 daily calories). Children have a high need for protein to support muscle growth and development. High levels of essential fatty acids are needed to support growth (although not as high as in infancy and the toddler years). As a result, the AMDR for fat is 25–35 percent of daily calories (33–47 grams for 1,200 daily calories). Children should get 17–25 grams of fiber per day.

Micronutrients

Micronutrient needs should be met with foods first. Parents and caregivers should select a variety of foods from each food group to ensure that nutritional requirements are met. Because children grow rapidly, they require foods that are high in iron, such as lean meats, legumes, fish, poultry, and iron-enriched cereals. Adequate fluoride is crucial to support strong teeth. One of the most important micronutrient requirements during childhood is adequate calcium and vitamin D intake. Both are needed to build dense bones and a strong skeleton. Children who do not consume adequate vitamin D should be given a supplement of 10 micrograms (400 international units) per day. Table 13.1 “Micronutrient Levels during Childhood” shows the micronutrient recommendations for school-aged children.[2] (Note that the recommendations are the same for boys and girls. As we progress through the different stages of the human life cycle, there will be some differences between males and females regarding micronutrient needs.)

| Nutrient | Children, Ages 4–8 |

|---|---|

| Vitamin A (mcg) | 400.0 |

| Vitamin B6 (mcg) | 600.0 |

| Vitamin B12 (mcg) | 1.2 |

| Vitamin C (mg) | 25.0 |

| Vitamin D (mcg) | 5.0 |

| Vitamin E (mg) | 7.0 |

| Vitamin K (mcg) | 55.0 |

| Calcium (mg) | 800.0 |

| Folate (mcg) | 200.0 |

| Iron (mg) | 10.0 |

| Magnesium (mg) | 130.0 |

| Niacin(B3) (mg) | 8.0 |

| Phosphorus (mg) | 500.0 |

| Riboflavin (B2) (mcg) | 600.0 |

| Selenium (mcg) | 30.0 |

| Thiamine (B1) (mcg) | 600.0 |

| Zinc (mg) | 5.0 |

Encouraging a Healthy Diet in Children and Adolescents

A healthy diet helps children grow and learn. It also helps prevent obesity and weight-related diseases, such as diabetes. To give your child a nutritious diet:[3]

- Make half of what is on your child’s plate fruits and vegetables

- Choose healthy sources of protein, such as lean meat, nuts, and eggs

- Serve whole-grain breads and cereals because they are high in fiber. Reduce refined grains.

- Broil, grill, or steam foods instead of frying them

- Limit fast food and junk food

- Offer water or milk instead of sugary fruit drinks and sodas

Factors Influencing Intake

A number of factors can influence children’s eating habits and attitudes toward food. Family environment, societal trends, taste preferences, and messages in the media all impact the emotions that children develop in relation to their diet. Television commercials can entice children to consume sugary products, fatty fast-foods, excess calories, refined ingredients, and sodium. Therefore, it is critical that parents and caregivers direct children toward healthy choices.

One way to encourage children to eat healthy foods is to make meal- and snack-time fun and interesting. Parents should include children in food planning and preparation, for example selecting items while grocery shopping or helping to prepare part of a meal, such as making a salad. At this time, parents can also educate children about kitchen safety. It might be helpful to cut sandwiches, meats, or pancakes into small or interesting shapes. In addition, parents should offer nutritious desserts, such as fresh fruits, instead of calorie-laden cookies, cakes, salty snacks, and ice cream. Also, studies show that children who eat family meals on a frequent basis consume more nutritious foods.[4]

Children and Malnutrition

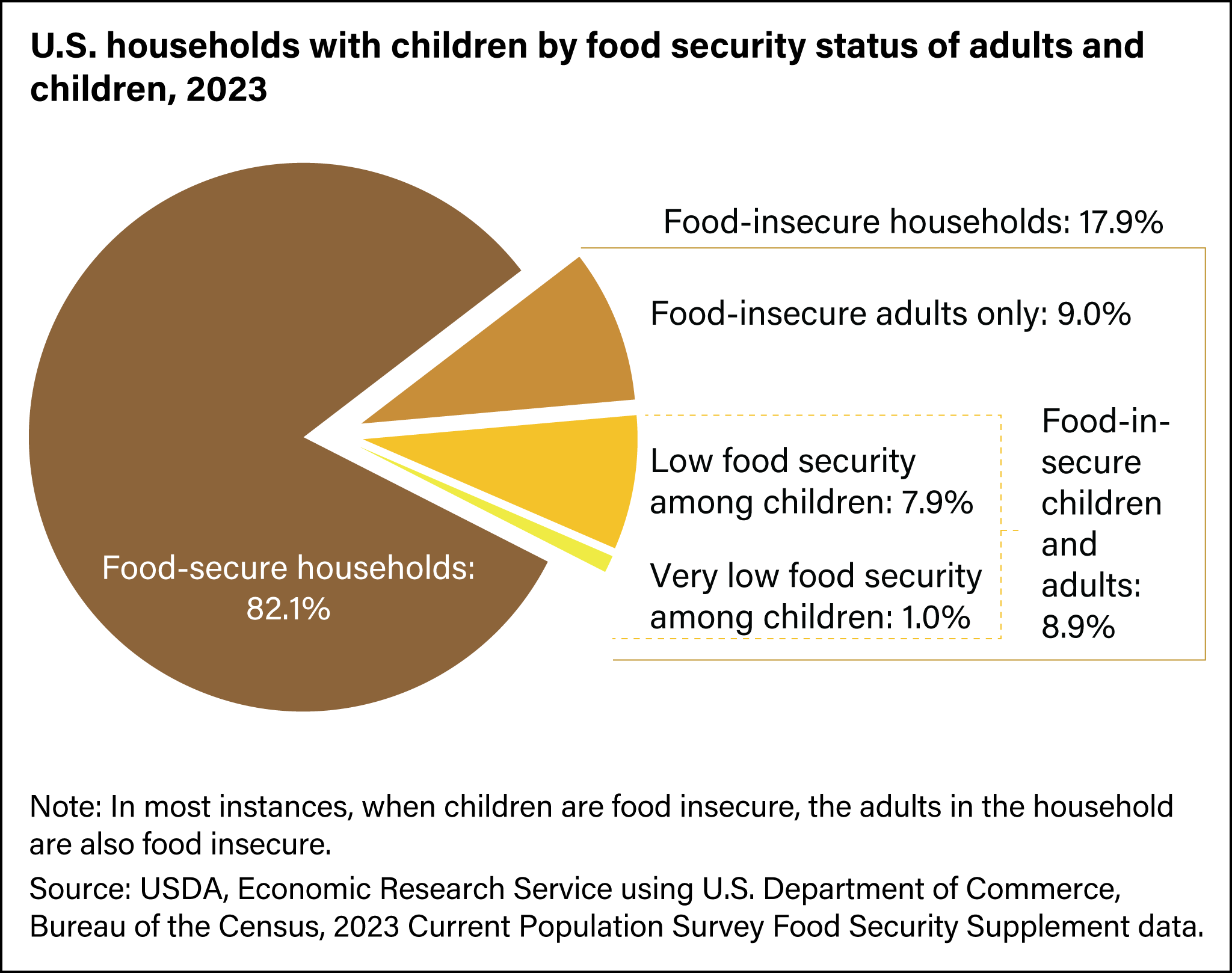

Malnutrition is a problem many children face, in both developing nations and the developed world. Even with the wealth of food in North America, many children grow up malnourished, or even hungry.An estimated 683,110 people in Louisiana live with food insecurity, 234,120 are children.[5] Over 21% of children in Louisiana come from food insecure homes. Food-secure children tend to perform better academically, have better health, and have a greater chance of achieving financial independence and overall well-being in life.[6] The US Census Bureau characterizes households into the following groups:

- food secure

- food insecure without hunger

- food insecure with moderate hunger

- food insecure with severe hunger

Millions of children grow up in food-insecure households with inadequate diets due to both the amount of available food and the quality of food. In the United States, about 20 percent of households with children are food insecure to some degree. In half of those, only adults experience food insecurity, while in the other half both adults and children are considered to be food insecure, which means that children did not have access to adequate, nutritious meals at times.[7]

Growing up in a food-insecure household can lead to a number of problems. Deficiencies in iron, zinc, protein, and vitamin A can result in stunted growth, illness, and limited development. Federal programs, such as the National School Lunch Program, the School Breakfast Program, and Summer Feeding Programs, work to address the risk of hunger and malnutrition in school-aged children. They help to fill the gaps and provide children living in food-insecure households with greater access to nutritious meals.

(Source USDA, Public Domain)

The National School Lunch Program

Beginning with preschool, children consume at least one of their meals in a school setting. Many children receive both breakfast and lunch outside of the home. Therefore, it is important for schools to provide meals that are nutritionally sound. In the United States, more than thirty-one million children from low-income families are given meals provided by the National School Lunch Program. The National School Lunch Program (NSLP) is a federally assisted meal program operating in public and nonprofit private schools and residential child care institutions. It provides nutritionally balanced, low-cost or free lunches to children each school day. The program was established under the National School Lunch Act, signed by President Harry Truman in 1946.[8] Updated December 24. School districts that take part receive subsidies from the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) for every meal they serve. School lunches must meet the Dietary Guidelines for Americans and need to provide one-third of the RDAs for protein, vitamin A, vitamin C, iron, and calcium. However, local authorities make the decisions about what foods to serve and how they are prepared.[9]

The Healthy School Lunch Campaign works to improve the food served to children in school and to promote children’s short- and long-term health by educating government officials, school officials, food-service workers, and parents. Sponsored by the Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine, this organization encourages schools to offer more low-fat, cholesterol-free options in school cafeterias and in vending machines.[10]

Food Allergies and Food Intolerance

Food Allergy

As discussed previously, the development of food allergies is a concern during the toddler years. This remains an issue for school-aged children as well.Food allergy is an immune system reaction that happens soon after eating a certain food. An allergy occurs when a protein in food triggers an immune response, which results in the release of antibodies, histamine, and other defenders that attack foreign bodies. Possible symptoms include Hives or red, itchy skin, stuffy or itchy nose, sneezing or itchy, teary eyes,nausea,vomiting, stomach cramps or diarrhea, angioedema or swelling.[11] Symptoms usually develop within minutes to hours after consuming a food allergen. Children can outgrow a food allergy, especially allergies to wheat, milk, eggs, or soy. Nine very common foods are responsible for the majority of allergic reactions: cow’s milk, eggs, fish, peanuts, sesame, shellfish, soy, tree nuts, wheat.[/footnote]Food Allergies: Symptoms, Diagnosis, & Treatment. American Academy of Allergy, asthma, and Immunology. https://www.aaaai.org/conditions-treatments/allergies/food-allergy. Accessed August 6, 2025.[/footnote] Even a tiny amount of the allergy-causing food can trigger symptoms such as hives, swollen airways and digestive problems.[12]

(Source: U.S. Food & Drug Administration, Public Domain)

Proper diagnosis of food allergies is extremely important. Studies have shown that many suspected food allergies are actually caused by other conditions such as a food intolerance. Skin tests, blood tests, or food challenges may be used to identify and confirm an allergy. While there is currently no cure for food allergies, there are preventative measures to manage the condition. The most important of these is avoiding coming in contact with food proteins that can cause an allergic reaction. Reading food labels and asking about ingredients when dining away from home are important strategies for staying informed about potential allergens.[13]

Anaphylaxis

Anaphylaxis is a life-threatening reaction that results in difficulty breathing, swelling in the mouth and throat, decreased blood pressure, shock, or even death. Milk, eggs, wheat, soybeans, fish, shellfish, peanuts, and tree nuts are the most likely to trigger this type of response. A dose of the drug epinephrine is often administered via a “pen” to treat a person who goes into anaphylactic shock.[14] Anaphylactic symptoms typically start in minutes to hours and then increase very rapidly to life-threatening levels. Urgent medical treatment is required to prevent serious harm and death, even if the patient has used an epinephrine autoinjector or has taken other medications in response, and even if symptoms appear to be improving. Table 13.2 “Anaphylaxis Signs and Symptoms” details the indications of anaphylactic reaction.[15]

| Body System | Likelihood system is part of anaphylactic response | Signs and Symptoms |

| Skin/Mucosa | 80-90% | Itchy, urticaria (hive) rash.

Progressive, painless swelling (angioedema) around the face and mouth, which may be preceded by itchiness, tearing, nasal congestion, or facial flushing. |

| Respiratory | 70% | Sneezing, coughing, wheezing, labored breathing, and upper airway swelling (indicated by hoarseness and/or difficulty swallowing) possibly causing airway obstruction. |

| Gastrointestinal | 45% | Crampy abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. |

| Cardiovascular | Up to 45% | Chest pain, palpitations, tachycardia, sudden reduction in blood pressure, or symptoms of end-organ dysfunction (e.g. hypotonia and incontinence). In infants symptoms may also include fussiness, irritability, drowsiness, or lethargy. |

| Central Nervous System | Up to 15% | Uneasiness, altered mental status, dizziness, or confusion. |

Food Intolerance

A food intolerance occurs when a person has difficulty digesting a specific food or nutrient, causing unpleasant GI symptoms such as gas, bloating, flatulence, cramping, and diarrhea. Food intolerances are commonly caused by the body not producing enough of a particular digestive enzyme, so the symptoms generally involve the digestive system, and the severity of symptoms usually correlates with how much of the food was eaten. Unlike food allergies, the immune system does not play a role in food intolerance, and while the symptoms are unpleasant, they are generally not dangerous and will subside once the food passes out of the GI tract. People with food intolerances can also often consume small amounts of the offending food without symptoms.[16] Common food intolerances include lactose, wheat, additives, fructose, caffeine and some natural food chemicals.

Lactose intolerance, though rare in very young children, is one example of a food intolerance. Children who suffer from this condition experience an adverse reaction to the lactose in milk products. It is a result of the small intestine’s inability to produce enough of the enzyme lactase, which is produced by the small intestine. Symptoms of lactose intolerance usually affect the GI tract and can include bloating, abdominal pain, gas, nausea, and diarrhea. An intolerance is best managed by making dietary changes and avoiding any foods that trigger the reaction.[17]

As with most food intolerances, people with lactose intolerance can often ingest a small amount of lactose without discomfort, although this varies from person to person. Aged hard cheese, buttermilk, and yogurt are often well-tolerated because they are low in lactose. In addition, lactose-free milk and lactase enzyme supplements are available. Dairy products are some of the main dietary sources of calcium and vitamin D, so individuals who avoid dairy need to take care to include other sources of these nutrients in their diets.[18]

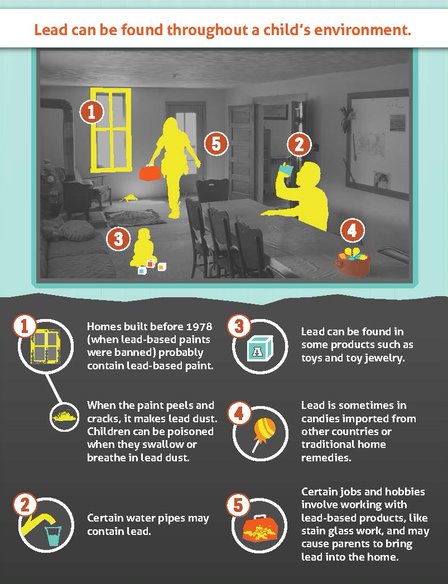

The Threat of Lead Toxicity

There is a danger of lead toxicity, or lead poisoning, among school-aged children. Lead is found in plumbing in old homes, in lead-based paint, and occasionally in the soil. Homes built before 1978 (when lead-based paints were banned) probably contain lead-based paint. When the paint peels and cracks, it makes lead dust. Children can be exposed to lead when they swallow or breathe in lead dust.[19] Contaminated food and water can increase exposure and result in hazardous lead levels in the blood. Children under age six are especially vulnerable. They may consume items tainted with lead, such as chipped, lead-based paint. Another common exposure is lead dust in carpets, with the dust flaking off of paint on walls. When children play or roll around on carpets coated with lead, they are in jeopardy. Lead is indestructible, and once it has been ingested it is difficult for the human body to alter or remove it. It can quietly build up in the body for months, or even years, before the onset of symptoms. Lead toxicity can damage the brain and central nervous system, resulting in impaired thinking, reasoning, and perception.

(Source Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Public Domain)

Treatment for lead poisoning includes removing the child from the source of contamination and extracting lead from the body. Extraction may involve chelation therapy, which binds with lead so it can be excreted in urine. Another treatment protocol, EDTA therapy, involves administering a drug called ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid to remove lead from the bloodstream of patients with levels greater than 45 mcg/dL.[20] Fortunately, lead toxicity is highly preventable. It involves identifying potential hazards, such as lead paint and pipes, and removing them before children are exposed to them.

Learning Activities

Technology Note: The second edition of the Human Nutrition Open Educational Resource (OER) textbook features interactive learning activities. These activities are available in the web-based textbook and not available in the downloadable versions (EPUB, Digital PDF, Print_PDF, or Open Document).

Learning activities may be used across various mobile devices, however, for the best user experience it is strongly recommended that users complete these activities using a desktop or laptop computer.

- Polan EU, Taylor DR. (2003). Journey Across the LifeSpan: Human Development and Health Promotion. Philadelphia: F. A. Davis Company, 150–51. ↵

- Institute of Medicine. 2006. Dietary Reference Intakes: The Essential Guide to Nutrient Requirements. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/11537. Accessed December 10, 2017. ↵

- Child Nutrition. Medline Plus. https://medlineplus.gov/childnutrition.html. Accessed August 5, 2025. ↵

- Research on the Benefits of Family Meals. Dakota County, Minnesota. https://www.co.dakota.mn.us/HealthFamily/HealthyLiving/DietNutrition/Documents/ReturnFamilyMeals.doc. Updated April 30, 2012. Accessed December 4, 2017. ↵

- Hunger in Louisiana : How Food Insecurity Affects Our Community. Feeding Louisiana. https://www.feedinglouisiana.org/hunger-in-louisiana#:~:text=Over%20234%2C120%20children%20in%20Louisiana,poverty%20in%20the%20US%C2%B2.. Accessed August 6, 2025. ↵

- Child Nutrition Programs. Feeding Louisiana. https://www.feedinglouisiana.org/initiatives/child-nutrition. Accessed August 6, 2025. ↵

- Coleman-Jensen A, et al. (2011). Household Food Security in the United States in 2010. US Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Report, no. ERR-125. ↵

- National School Lunch Program | Food and Nutrition Service ↵

- National School Lunch Program Fact Sheet. US Department of Agriculture. https://www.fns.usda.gov/fns-101-nslp. Published 2021. Accessed August 6, 2025. ↵

- Healthy School Food. Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine. https://www.pcrm.org/good-nutrition/healthy-communities/healthy-school-food. Accessed August 6, 2025. ↵

- Food Allergies: Symptoms, Diagnosis, & Treatment. American Academy of Allergy, asthma, and Immunology. https://www.aaaai.org/conditions-treatments/allergies/food-allergy. Accessed August 6, 2025. ↵

- Food Allergy: Symptoms & Causes. Mayo Clinic. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/food-allergy/symptoms-causes/syc-20355095. Accessed August 6, 2025. ↵

- Food Allergies: Symptoms, Diagnosis, & Treatment. American Academy of Allergy, asthma, and Immunology. https://www.aaaai.org/conditions-treatments/allergies/food-allergy. Accessed August 6, 2025. ↵

- Food Allergy: Symptoms & Causes. Mayo Clinic. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/food-allergy/symptoms-causes/syc-20355095. Accessed August 6, 2025. ↵

- St. Amant, O., et al (2019). 4.6 Anaphylaxis. Vaccine Practice for Health Professionals. https://med.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Nursing/Book%3A_Vaccine_Practice_for_Health_Professionals_(St-Amant_Lapum_Dubey_Beckermann_Huang_Weeks_Leslie_and_English)/04%3A_Vaccine_Safety/4.06%3A_Anaphylaxis. Accessed August 6, 2025. ↵

- Shanle, E. K. and Dowell J. (2025). Food Intolerances, Allergies, and Celiac Disease. An Introduction to Human Nutrition. https://med.libretexts.org/Courses/Lincoln_Land_Community_College/An_Introduction_to_Human_Nutrition_(Shanle_and_Dowell)/04%3A_Basics_of_Digestion/4.05%3A_Food_Intolerances_Allergies_and_Celiac_Disease. Accessed August 6, 2025. ↵

- Lactose Intolerance. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. http://digestive.niddk.nih.gov/ddiseases/pubs/lactoseintolerance/. Accessed August 6, 2025. ↵

- Shanle, E. K. and Dowell J. (2025). Food Intolerances, Allergies, and Celiac Disease. An Introduction to Human Nutrition. https://med.libretexts.org/Courses/Lincoln_Land_Community_College/An_Introduction_to_Human_Nutrition_(Shanle_and_Dowell)/04%3A_Basics_of_Digestion/4.05%3A_Food_Intolerances_Allergies_and_Celiac_Disease. Accessed August 6, 2025. ↵

- Preventing Childhood Lead Poisoning:Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/lead-prevention/prevention/index.html. Accessed August 6, 2025 ↵

- Lead Poisoning: Diagnosis and Treatment. Mayo Clinic. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/lead-poisoning/diagnosis-treatment/drc-20354723 . Accessed August 6, 2025. ↵

is the first menstrual cycle, or first menstrual bleeding, in female humans.

Spermarche, also known as semenarche, is the time at which a male experiences his first ejaculation

Food that is high in nutrients but relatively low in calories

(Acceptable Macronutrient Distribution Ranges) A range of intakes for carbohydrates, fat, and protein expressed as a percentage of total energy intake for normal healthy individuals.

state or condition of being overweight.

any one of a group of diseases that affect how the body uses blood sugar (glucose).

A situation where people lack adequate physical, social or economic access to sufficient and nutritious foods that meets their dietary needs.

A federal program designed to provide free or reduced cost lunches to school-age children.

Preschool refers to an early childhood program in which children combine learning with play.

An adverse immune response to specific protein.

A condition that results from the inability to digest lactose. Symptoms include bloating, gas, abdominal pain, discomfort, and diarrhea.

an enzyme in the milk that catalyzes the hydrolysis of lactose to glucose and galactose.

The organ system that includes the brain and spinal cord responsible for sensing changes in the external environment and creating a reaction to them.