Introduction

“You don’t need a silver fork to eat good food”

– Chef Paul Prudhomme

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Describe the function and role of lipids in the body

- Describe the process of lipid digestion and absorption

- Describe tools and approaches for balancing your diet with lipids

Pecans are a rich source of manganese, copper, zinc, and magnesium. Louisiana is ranked among the top five producers of pecans in the United States, harvesting over 17 million pounds of pecans per year.[1] The state has an enormous amount of native pecan trees and is home to one of the largest “yard crops” of pecans in the southern region of the US. Pecans are usually hand-harvested by residents who have pecan-bearing trees in their yards. Dating back to 1845, a New Orleans slave named Antoine was the first person to produce new pecan plants, which he named Centennial, through a technique known as grafting. His new technique for planting and producing Centennial pecan trees pioneered the success of the pecan industry in Louisiana. Traditionally, Louisianaians use pecans for cooking and baking staple southern dishes unique to the region, such as pecan pie, pecan candy or pralines, and various cakes.

Pecans contain a significant amount of monounsaturated fatty acids and tocopherols, which can aid in lipid balance, improve heart health and blood sugar levels, and contribute to weight loss. Research studies suggest that including pecans in the diet can contribute to higher energy levels and healthy weight management.[2] Pecans are usually harvested in late September. Therefore, pecans can be an excellent nutrient source in the fall and winter seasons.

Lipids are important molecules that serve different roles in the human body. A common misconception is that fat is simply fattening. However, fat is probably the reason we are all here. Throughout history, there have been many instances when food was scarce. Our ability to store excess caloric energy as fat for future usage allowed us to continue as a species during these times of famine. So, normal fat reserves are a signal that metabolic processes are efficient and a person is healthy.

Lipids are a family of organic compounds that are mostly insoluble in water. Composed of fats and oils, lipids are molecules that yield high energy and have a chemical composition mainly of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen. Lipids perform three primary biological functions within the body: they serve as structural components of cell membranes, function as energy storehouses, and function as important signaling molecules.

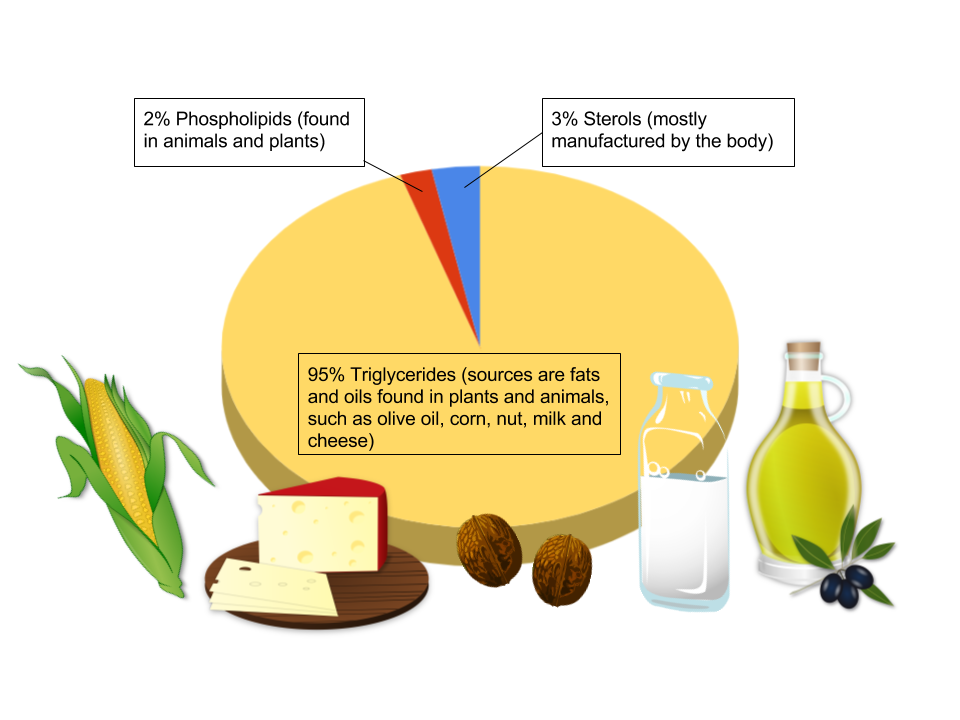

The three main types of lipids are triglycerides, phospholipids, and sterols. Triglycerides comprise more than 95 percent of lipids in the diet and are commonly found in fried foods, vegetable oil, butter, whole milk, cheese, cream cheese, and some meats. Naturally occurring triglycerides are found in many foods, including avocados, olives, corn, and nuts. We commonly call the triglycerides in our food “fats” and “oils.” Fats are solid lipids at room temperature, whereas oils are liquid. As with most fats, triglycerides do not dissolve in water. The terms fats, oils, and triglycerides are interchangeable and can be used interchangeably. In this chapter, when we use the word fat, we refer to triglycerides.

Phospholipids make up only about 2 percent of dietary lipids. They are water-soluble and are found in both plants and animals. Phospholipids are crucial for building the protective barrier, or membrane, around your body’s cells. Phospholipids are synthesized in the body to form cell and organelle membranes. In blood and body fluids, phospholipids form structures where fat is enclosed and transported throughout the bloodstream.

Sterols are the least common type of lipid. Cholesterol is perhaps the best-known sterol. Though cholesterol has a notorious reputation, the body gets only a small amount of its cholesterol through food—the body produces most of it. Cholesterol is an important component of the cell membrane and is required for the synthesis of sex hormones, and bile salts.

Later in this chapter, we will examine each of these lipids in more detail and discover how their different structures function to keep your body working.

(Source: University of Hawaii @ Manoa, Allison Calabrese, CC-BY-NC-SA

Learning Activities

Technology Note: The second edition of the Human Nutrition Open Educational Resource (OER) textbook features interactive learning activities. These activities are available in the web-based textbook and are not in downloadable versions (EPUB, Digital PDF, Print_PDF, or Open Document).

Learning activities may be used across various mobile devices; however, for the best user experience, it is strongly recommended that users complete these activities using a desktop or laptop computer.

- Louisiana Commodities: Pecans. Ag in the Classroom. https://aitcla.org/pecans. Accessed July 22, 2025. ↵

- Morgan, W.A. & Claushulte, B.I., 2000.Pecans Lower Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol in People with Normal Lipid Levels. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 100(3): 312-318. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10719404/. Accessed July 21, 2025. ↵

A chemical messenger in the body that is released into the blood from one specific location in the body and travels to another location, where it elicits a specific response.