The intramuscular (IM) injection route is used to place medication in muscle tissue. Muscle has an abundant blood supply that allows medications to be absorbed faster than the subcutaneous route.

Factors that influence the choice of muscle to use for an intramuscular injection include the patient’s size, as well as the amount, viscosity, and type of medication. The length of the needle must be long enough to pass through the subcutaneous tissue to reach the muscle, so needles up to 1.5 inches long may be selected. However, if a patient is thin, a shorter needle length is used because there is less fat tissue to advance through to reach the muscle. Additionally, the muscle mass of infants and young children cannot tolerate large amounts of medication volume. Medication fluid amounts up to 0.5-1 mL can be injected in one site in infants and children, whereas adults can tolerate 2-3 mL. Intramuscular injections are administered at a 90-degree angle. Research has found administering medications at 10 seconds per mL is an effective rate for IM injections, but always review the drug administration rate per pharmacy or manufacturer’s recommendations.[1]

Anatomic Sites

Anatomic sites must be selected carefully for intramuscular injections and include the ventrogluteal, vastus lateralis, and the deltoid. The vastus lateralis site is preferred for infants because that muscle is most developed. The ventrogluteal site is generally recommended for IM medication administration in adults, but IM vaccines may be administered in the deltoid site. Additional information regarding injections in each of these sites is provided in the following subsections.

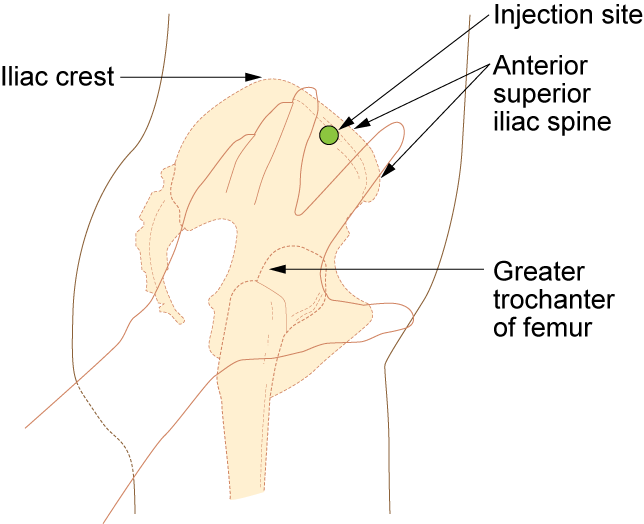

Ventrogluteal

This site involves the gluteus medius and minimus muscle and is the safest injection site for adults and children because it provides the greatest thickness of gluteal muscles, is free from penetrating nerves and blood vessels, and has a thin layer of fat. To locate the ventrogluteal site, place the patient in a supine or lateral position. Use your right hand for the left hip or your left hand for the right hip. Place the heel or palm of your hand on the greater trochanter, with the thumb pointed toward the belly button. Extend your index finger to the anterior superior iliac spine and spread your middle finger pointing towards the iliac crest. Insert the needle into the “V” formed between your index and middle fingers. This is the preferred site for all oily and irritating solutions for patients of any age.[2] See Figure 18.31[3] for an image demonstrating how to accurately locate the ventrogluteal site using your hand.

The needle gauge used at the ventrogluteal site is determined by the solution of the medication ordered. An aqueous solution can be given with a 20- to 25-gauge needle, whereas viscous or oil-based solutions are given with 18- to 21-gauge needles. The needle length is based on patient weight and body mass index. A thin adult may require a 5/8-inch to 1-inch (16 mm to 25 mm) needle, while an average adult may require a 1-inch (25 mm) needle, and a larger adult (over 70 kg) may require a 1-inch to 1½-inch (25 mm to 38 mm) needle. Children and infants require shorter needles. Refer to agency policies regarding needle length for infants, children, and adolescents. Up to 3 mL of medication may be administered in the ventrogluteal muscle of an average adult and up to 1 mL in children. See Figure 18.32[4] for an image of locating the ventrogluteal site on a patient.

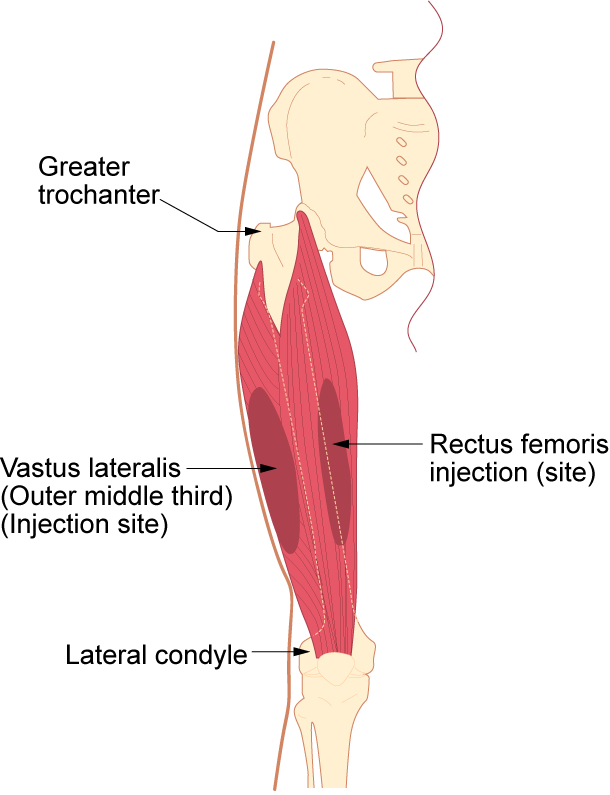

Vastus Lateralis

The vastus lateralis site is commonly used for immunizations in infants and toddlers because the muscle is thick and well-developed. This muscle is located on the anterior lateral aspect of the thigh and extends from one hand’s breadth above the knee to one hand’s breadth below the greater trochanter. The outer middle third of the muscle is used for injections. To help relax the patient, ask the patient to lie flat with knees slightly bent or have the patient in a sitting position. See Figure 18.33[5] for an image of the vastus lateralis injection site.

The length of the needle used at the vastus lateralis site is based on the patient’s age, weight, and body mass index. In general, the recommended needle length for an adult is 1 inch to 1 ½ inches (25 mm to 38 mm), but the needle length is shorter for children. Refer to agency policy for pediatric needle lengths. The gauge of the needle is determined by the type of medication administered. Aqueous solutions can be given with a 20- to 25-gauge needle; oily or viscous medications should be administered with 18- to 21-gauge needles. A smaller gauge needle (22 to 25 gauge) should be used with children. The maximum amount of medication for a single injection in an adult is 3 mL. See Figure 18.34[6] for an image of an intramuscular injection being administered at the vastus lateralis site.

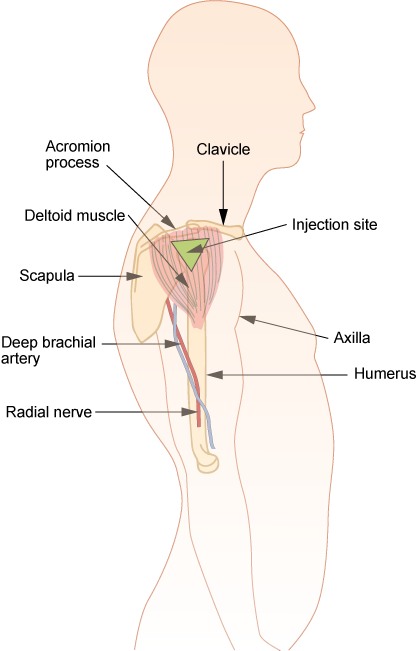

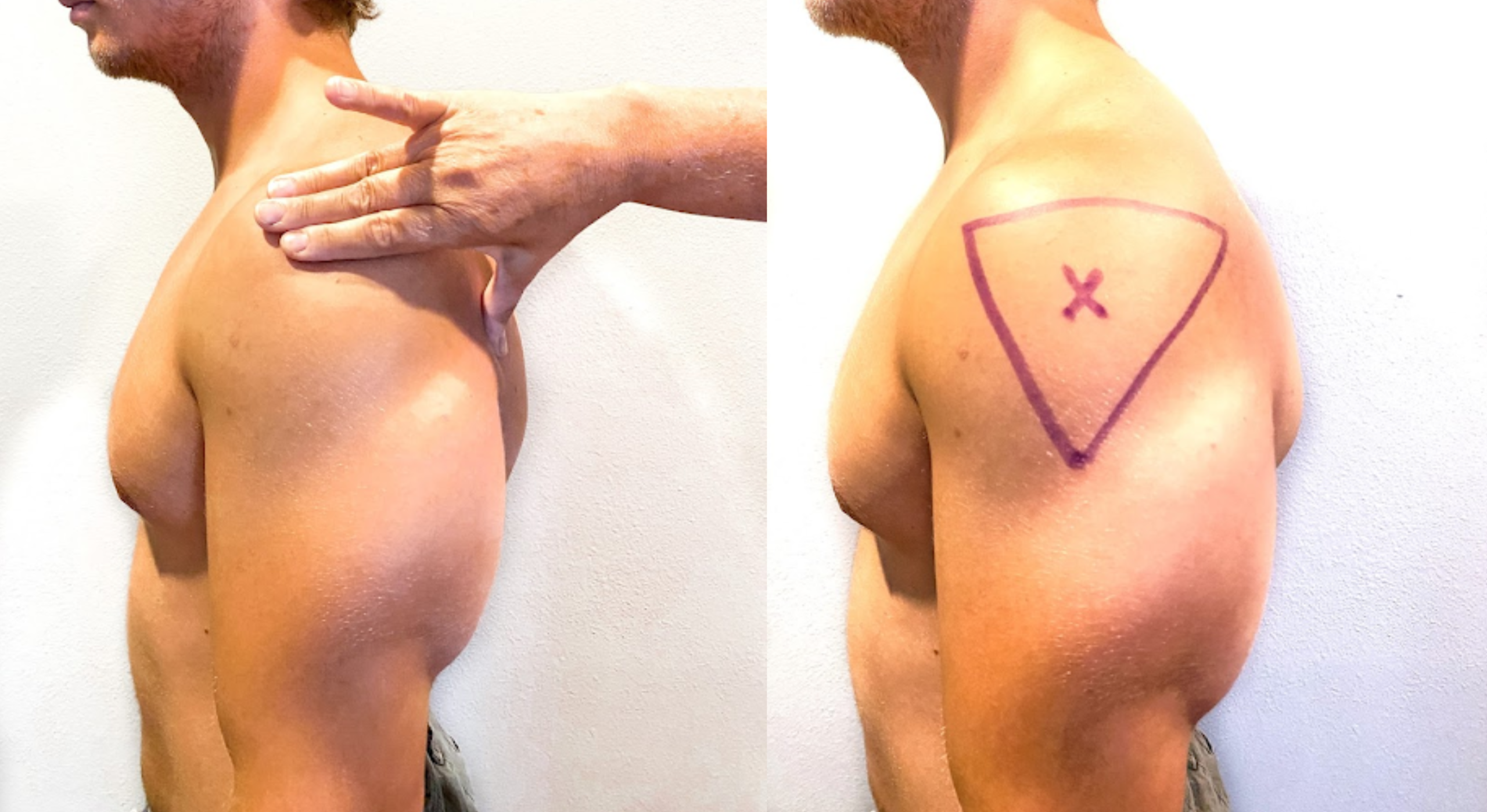

Deltoid

The deltoid muscle has a triangular shape and is easy to locate and access. To locate the injection site, begin by having the patient relax their arm. The patient can be standing, sitting, or lying down. To locate the landmark for the deltoid muscle, expose the upper arm and find the acromion process by palpating the bony prominence. The injection site is in the middle of the deltoid muscle, about 1 inch to 2 inches (2.5 cm to 5 cm) below the acromion process. To locate this area, lay three fingers across the deltoid muscle and below the acromion process. The injection site is generally three finger widths below in the middle of the muscle. See Figure 18.35[7] for an illustration for locating the deltoid injection site.

Select the needle length based on the patient’s age, weight, and body mass. In general, for an adult male weighing 60 kg to 118 kg (130 to 260 lbs), a 1-inch (25 mm) needle is sufficient. For women under 60 kg (130 lbs), a ⅝-inch (16 mm) needle is sufficient, while for women between 60 kg and 90 kg (130 to 200 lbs) a 1-inch (25 mm) needle is required. A 1 ½-inch (38 mm) length needle may be required for women over 90 kg (200 lbs) for a deltoid IM injection. For immunizations, a 22- to 25-gauge needle should be used. Refer to agency policy regarding specifications for infants, children, adolescents, and immunizations. The maximum amount of medication for a single injection is generally 1 mL. See Figure 18.36[8] for an image of locating the deltoid injection site on a patient.

Description of Procedure

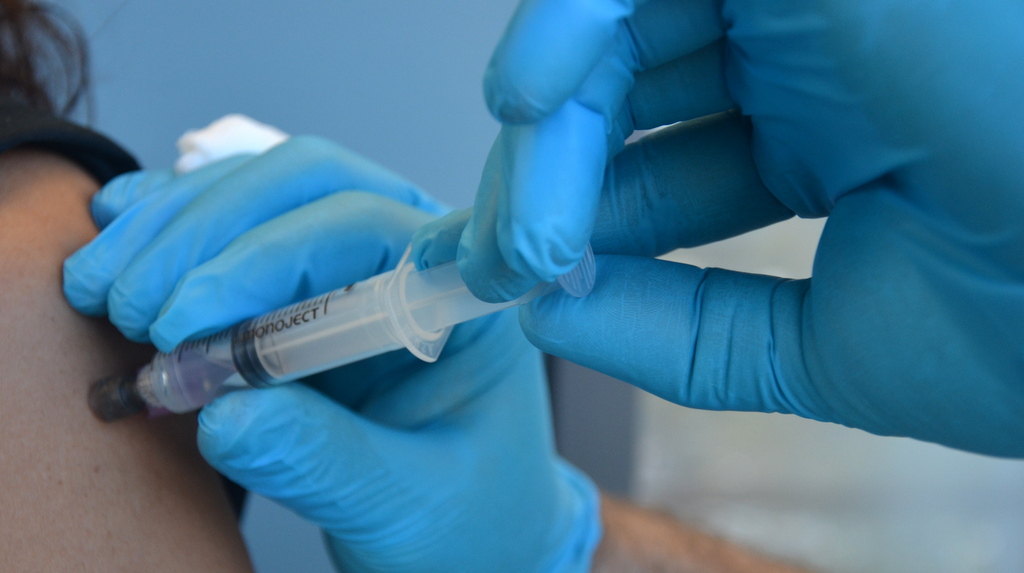

When administering an intramuscular injection, the procedure is similar to a subcutaneous injection, but instead of pinching the skin, stabilize the skin around the injection site with your nondominant hand. With your dominant hand, hold the syringe like a dart and insert the needle quickly into the muscle at a 90-degree angle using a steady and smooth motion. After the needle pierces the skin, use the thumb and forefinger of the nondominant hand to hold the syringe. If aspiration is indicated according to agency policy and manufacturer recommendations, pull the plunger back to aspirate for blood. If no blood appears, inject the medication slowly and steadily. If blood appears, discard the syringe and needle and prepare the medication again. See Figure 18.37[9] for an image of aspirating for blood. After the medication is completely injected, leave the needle in place for ten seconds, and then remove the needle using a smooth, steady motion. Remove the needle at the same angle at which it was inserted. Cover the injection site with sterile gauze using gentle pressure and apply a Band-Aid if needed.[10]

Z-track Method for IM injections

Evidence-based practice supports using the Z-track method for administration of intramuscular injections. This method prevents the medication from leaking into the subcutaneous tissue, allows the medication to stay in the muscles, and can minimize irritation.[12]

The Z-track method creates a zigzag path to prevent medication from leaking into the subcutaneous tissue. This method may be used for all injections or may be specified by the medication.

Displace the patient’s skin in a Z-track manner by pulling the skin down or to one side about 1 inch (2 cm) with your nondominant hand before administering the injection. With the skin held to one side, quickly insert the needle at a 90-degree angle. After the needle pierces the skin, continue pulling on the skin with the nondominant hand, and at the same time, grasp the lower end of the syringe barrel with the fingers of the nondominant hand to stabilize it. Move your dominant hand and pull the end of the plunger to aspirate for blood, if indicated. If no blood appears, inject the medication slowly. Once the medication is given, leave the needle in place for ten seconds. After the medication is completely injected, remove the needle using a smooth, steady motion, and then release the skin. See Figure 18.38[13] for an illustration of the Z-track method.

![“Z-track-process-1.png“ and "Z-track-process-3.png" by British Columbia Institute of Technology (BCIT) is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://opentextbc.ca/clinicalskills/chapter/6-8-iv-push-medications-and-saline-lock-flush/[/footnote] Illustration showing two parts of the Z track method](https://louis.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/141/2025/08/ztrack-1-scaled-1.png)

Special Considerations for IM Injections

- Avoid using sites with atrophied muscle because they will poorly absorb medications.

- If repeated IM injections are given, sites should be rotated to decrease the risk of hypertrophy.

- Older adults and thin patients may only tolerate up to 2 milliliters in a single injection.

- Choose a site that is free from pain, infection, abrasions, or necrosis.

- The dorsogluteal site should be avoided for intramuscular injections because of the risk for injury. If the needle inadvertently hits the sciatic nerve, the patient may experience partial or permanent paralysis of the leg.

View supplementary YouTube videos on Administering Intramuscular Injections:

Z-Track Method[14]

Ventrogluteal Injection[15]

- This work is a derivative of Clinical Procedures for Safer Patient Care by British Columbia Institute of Technology and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Clinical Procedures for Safer Patient Care by British Columbia Institute of Technology and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “Im-ventrogluteal-300x244.png” by British Columbia Institute of Technology is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://opentextbc.ca/clinicalskills/chapter/6-8-iv-push-medications-and-saline-lock-flush/ ↵

- “Injection Site Image1.heic” by Meredith Pomietlo for Chippewa Valley Technical College is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “Im-vastus-lateralis.png” by British Columbia Institute of Technology is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://opentextbc.ca/clinicalskills/chapter/6-7-intradermal-subcutaneous-and-intramuscular-injections/ ↵

- “Vastus Lateralis Site” by Meredith Pomietlo for Chippewa Valley Technical College is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “Im-deltoid.png” by British Columbia Institute of Technology is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://opentextbc.ca/clinicalskills/chapter/6-7-intradermal-subcutaneous-and-intramuscular-injections/ ↵

- “Injection Site Image 3.jpg” and "Injection Site Image 2.jpg" by Meredith Pomietlo for Chippewa Valley Technical College are licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “Sept-22-2015-111.jpg” by British Columbia Institute of Technology is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://opentextbc.ca/clinicalskills/chapter/6-8-iv-push-medications-and-saline-lock-flush/ ↵

- This work is a derivative of Clinical Procedures for Safer Patient Care by British Columbia Institute of Technology and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019, April 15). Vaccine administration. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/vac-admin.html ↵

- Yilmaz, D., Khorshid, L., & Dedeoğlu, Y. (2016). The effect of the z-track technique on pain and drug leakage in intramuscular injections. Clinical Nurse Specialist, 30(6), E7-E12. https://doi.org/10.1097/nur.0000000000000245 ↵

- “Z-track-process-1.png” and “Z-track-process-3.png” by British Columbia Institute of Technology are licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://opentextbc.ca/clinicalskills/chapter/6-8-iv-push-medications-and-saline-lock-flush/ ↵

- RegisteredNurseRN. (2018, November 19). Intramuscular injection in deltoid muscle with z-track technique [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. Video used with permission. https://youtu.be/DBHnd3N-5Ns ↵

- RegisteredNurseRN. (2014, August 8). How to give an IM intramuscular injection ventrogluteal buttock muscle [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. Video used with permission. https://youtu.be/wKCPiSnYqwA ↵

Hand hygiene should be performed during select moments of patient care: immediately before touching a patient; before performing an aseptic task or handling invasive devices; before moving from a soiled body site to a clean body site on a patient; after touching a patient or their immediate environment; after contact with blood, body fluids, or contaminated surfaces (with or without glove use); and immediately after glove removal.

Infection prevention and control interventions to be used in addition to standard precautions; used for diseases spread by large respiratory droplets such as influenza, COVID-19, or pertussis.

Infection prevention and control interventions to be used in addition to standard precautions; used for diseases spread by large respiratory droplets such as influenza, COVID-19, or pertussis.

Standard Versus Transmission-Based Precautions

Standard Precautions

Standard precautions are used when caring for all patients to prevent health care associated infections. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), standard precautions are “the minimum infection prevention practices that apply to all patient care, regardless of suspected or confirmed infection status of the patient, in any setting where health care is delivered.”[1] They are based on the principle that all blood, body fluids (except sweat), nonintact skin, and mucous membranes may contain transmissible infectious agents. These standards reduce the risk of exposure for the health care worker and protect the patient from potential transmission of infectious organisms.

Current standard precautions according to the CDC (2019) include the following:

- Appropriate hand hygiene

- Use of personal protective equipment (e.g., gloves, gowns, masks, eyewear) whenever infectious material exposure may occur

- Appropriate patient placement and care using transmission-based precautions when indicated

- Respiratory hygiene/cough etiquette

- Proper handling and cleaning of environment, equipment, and devices

- Safe handling of laundry

- Sharps safety (i.e., engineering and work practice controls)

- Aseptic technique for invasive nursing procedures such as parenteral medication administration[2]

Each of these standard precautions is described in more detail in the following subsections.

Transmission-Based Precautions

In addition to standard precautions, transmission-based precautions are used for patients with documented or suspected infection, or colonization, of highly transmissible or epidemiologically important pathogens. Epidemiologically important pathogens include, but are not limited to, Coronavirus disease (COVID-19), Clostridium difficile (C-diff), Methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), Vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE), Respiratory syncytial sirus (RSV), measles, and tuberculosis (TB). For patients with these types of pathogens, standard precautions are used along with specific transmission-based precautions.

There are four categories of transmission-based precautions: contact precautions, enhanced barrier precautions, droplet precautions, and airborne precautions. Transmission-based precautions are used when the route(s) of transmission is (are) not completely interrupted using standard precautions alone. Some diseases, such as tuberculosis, have multiple routes of transmission so more than one transmission-based precautions category must be implemented. See Table 4.2 outlining the categories of transmission precautions with associated PPE and other precautions. When possible, patients with transmission-based precautions should be placed in a single occupancy room with dedicated patient care equipment (e.g., blood pressure cuffs, stethoscope, thermometer). Transport of the patient and unnecessary movement outside the patient room should be limited. However, when transmission-based precautions are implemented, it is also important for the nurse to make efforts to counteract possible adverse effects of these precautions on patients, such as anxiety, depression, perceptions of stigma, and reduced contact with clinical staff.

Table 4.2 Transmission-Based Precautions[3]

| Precaution | Implementation | PPE and Other Precautions |

|---|---|---|

| Contact | Known or suspected infections with increased risk for contact transmission (e.g., draining wounds, fecal incontinence) or with epidemiologically important organisms, such as C-diff, MRSA, VRE, or RSV |

Note: Use only soap and water for hand hygiene in patients with C. difficile infection. |

| Enhanced barrier | Used during high-contact resident care activities for individuals colonized or infected with a multidrug-resistant organism (MDRO), as well as those at increased risk of MDRO acquisition |

|

| Droplet | Known or suspected infection with pathogens transmitted by large respiratory droplets generated by coughing, sneezing, or talking, such as influenza, coronavirus, or pertussis |

|

| Airborne | Known or suspected infection with pathogens transmitted by small respiratory droplets, such as measles, tuberculosis, and disseminated herpes zoster | Fit-tested N-95 respirator or PAPR

|

View a list of transmission-based precautions used for specific medical conditions at the CDC Guideline for Isolation Precautions.

Patient Transport

Several principles are used to guide transport of patients requiring transmission-based precautions. In the inpatient and residential settings, these principles include the following:

- Limiting transport for essential purposes only, such as diagnostic and therapeutic procedures that cannot be performed in the patient’s room

- Using appropriate barriers on the patient consistent with the route and risk of transmission (e.g., mask, gown, covering the affected areas when infectious skin lesions or drainage is present)

- Notify other health care personnel involved in the care of the patient of the transmission-based precautions. For example, when transporting the patient to radiology, inform the radiology technician of the precautions.[4]

Appropriate Hand Hygiene

Hand hygiene is the single most important practice to reduce the transmission of infectious agents in health care settings and is an essential element of standard precautions.[5] Routine handwashing during appropriate moments is a simple and effective way to prevent infection. However, it is estimated that health care professionals, on average, properly clean their hands less than 50% of the time it is indicated.[6] The Joint Commission, the organization that sets evidence-based standards of care for hospitals, recently updated its hand hygiene standards in 2018 to promote enforcement. If a Joint Commission surveyor witnesses an individual failing to properly clean their hands when it is indicated, a deficiency will be cited requiring improvement by the agency. This deficiency could potentially jeopardize a hospital’s accreditation status and their ability to receive payment for patient services. Therefore, it is essential for all health care workers to ensure they are using proper hand hygiene at the appropriate times.[7]

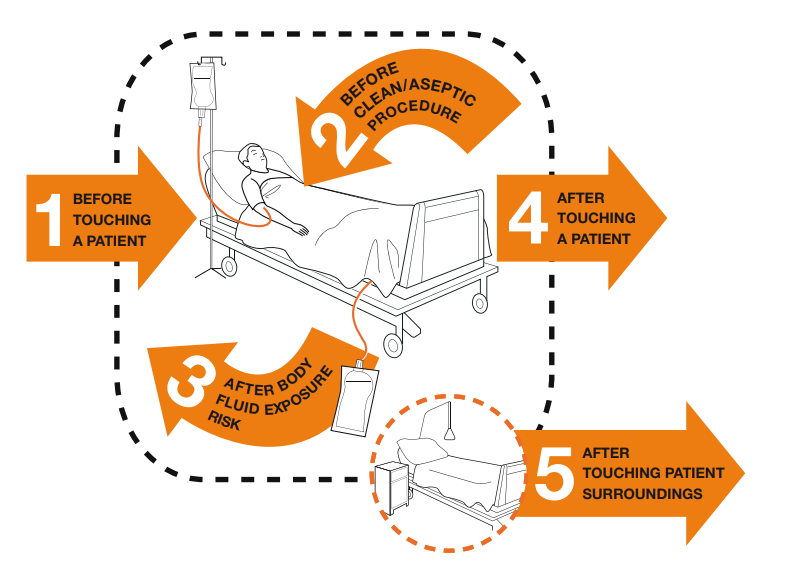

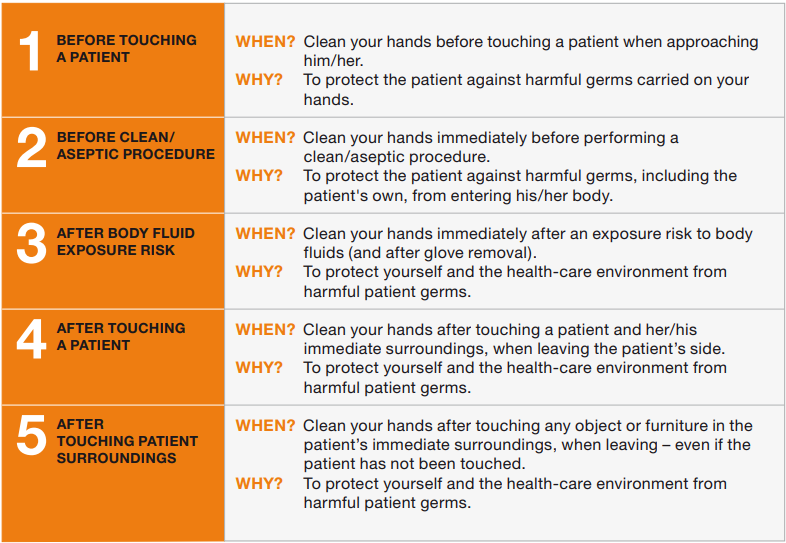

There are several evidence-based guidelines for performing appropriate hand hygiene. These guidelines include frequency of performing hand hygiene according to the care circumstances, solutions used, and technique performed. The Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC) recommends health care personnel perform hand hygiene at specific times when providing care to patients. These moments are often referred to as the “Moments for Hand Hygiene.”[8] See Figures 4.1[9] and 4.2[10] for an illustration and application of the five moments of hand hygiene. The five moments of hand hygiene are as follows:

- Immediately before touching a patient

- Before performing an aseptic task or handling invasive devices

- Before moving from a soiled body site to a clean body site on a patient

- After touching a patient or their immediate environment

- After contact with blood, body fluids, or contaminated surfaces (with or without glove use)

When performing hand hygiene, washing with soap and water, or an approved alcohol-based hand rub solution that contains at least 60% alcohol, may be used. Unless hands are visibly soiled, an alcohol-based hand rub is preferred over soap and water in most clinical situations due to evidence of improved compliance. Handrubs are also preferred because they are generally less irritating to health care worker’s hands. However, it is important to recognize that alcohol-based rubs do not eliminate some types of germs, such as Clostridium difficile (C-diff).

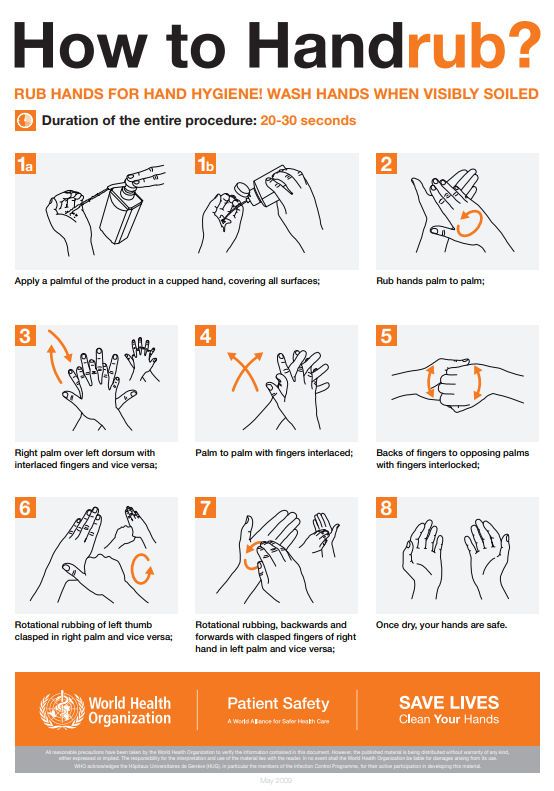

When using the alcohol-based handrub method, the CDC recommends the following steps. See Figure 4.3[11] for a handrub poster created by the World Health Organization.

- Apply product to the palm of one hand in an amount that will cover all surfaces.

- Rub hands together, covering all the surfaces of the hands, fingers, and wrists until the hands are dry. Surfaces include the palms and fingers, between the fingers, the backs of the hands and fingers, the fingertips, and the thumbs.

- The process should take about 20 seconds, and the solution should be dry.[12]

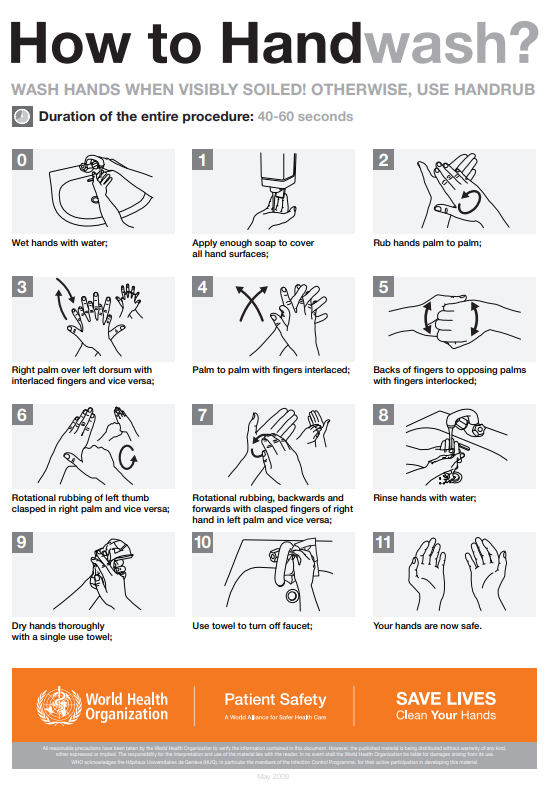

When washing with soap and water, the CDC recommends using the following steps. See Figure 4.4[13] for an image of a handwashing poster created by the World Health Organization.

- Wet hands with warm or cold running water and apply facility-approved soap.

- Lather hands by rubbing them together with the soap. Use the same technique as the handrub process to clean the palms and fingers, between the fingers, the backs of the hands and fingers, the fingertips, and the thumbs.

- Scrub thoroughly for at least 20 seconds.

- Rinse hands well under clean, running water.

- Dry the hands using a clean towel or disposable toweling.

- Use a clean paper towel to shut off the faucet.[14]

By performing hand hygiene at the proper moments and using appropriate techniques, you will ensure your hands are safe and you are not transmitting infectious organisms to yourself or others.

Hand Hygiene for Healthcare Workers on YouTube[15]

Personal Protective Equipment (PPE)

Personal protective equipment (PPE) includes gloves, gowns, face shields, goggles, and masks used to prevent the spread of infection to and from patients and health care providers. Depending on the anticipated exposure, PPE may include the use of gloves, a fluid-resistant gown, goggles or a face shield, and a mask or respirator. When used for a patient with transmission-based precautions, PPE supplies are typically stored in an isolation cart next to the patient’s room, and a card is posted on the door alerting staff and visitors to precautions needed before entering the room.

Gloves

Gloves protect both patients and health care personnel from exposure to infectious material that may be carried on the hands. Gloves are used to prevent contamination of health care personnel hands during activities such as the following:

- Anticipating direct contact with blood or body fluids, mucous membranes, nonintact skin, and other potentially infectious material

- Having direct contact with patients who are colonized or infected with pathogens transmitted by the contact route, such as Vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE), Methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), and Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV)

- Handling or touching visibly or potentially contaminated patient care equipment and environmental surfaces[16]

Nonsterile disposable medical gloves for routine patient care are made of a variety of materials, such as latex, vinyl, and nitrile. Many people are allergic to latex, so be sure to check for latex allergies for the patient and other health care professionals. See Figure 4.5[17] for an image of nonsterile medical gloves in various sizes in a health care setting. At times, gloves may need to be changed when providing care to a single patient to prevent cross-contamination of body sites. It is also necessary to change gloves if the patient interaction requires touching portable computer keyboards or other mobile equipment that is transported from room to room. Discarding gloves between patients is necessary to prevent transmission of infectious material. Gloves must not be washed for subsequent reuse because microorganisms cannot be reliably removed from glove surfaces, and continued glove integrity cannot be ensured.[18]

When gloves are worn in combination with other PPE, they are put on last. Gloves that fit snugly around the wrist should be used in combination with isolation gowns because they will cover the gown cuff and provide a more reliable continuous barrier for the arms, wrists, and hands.

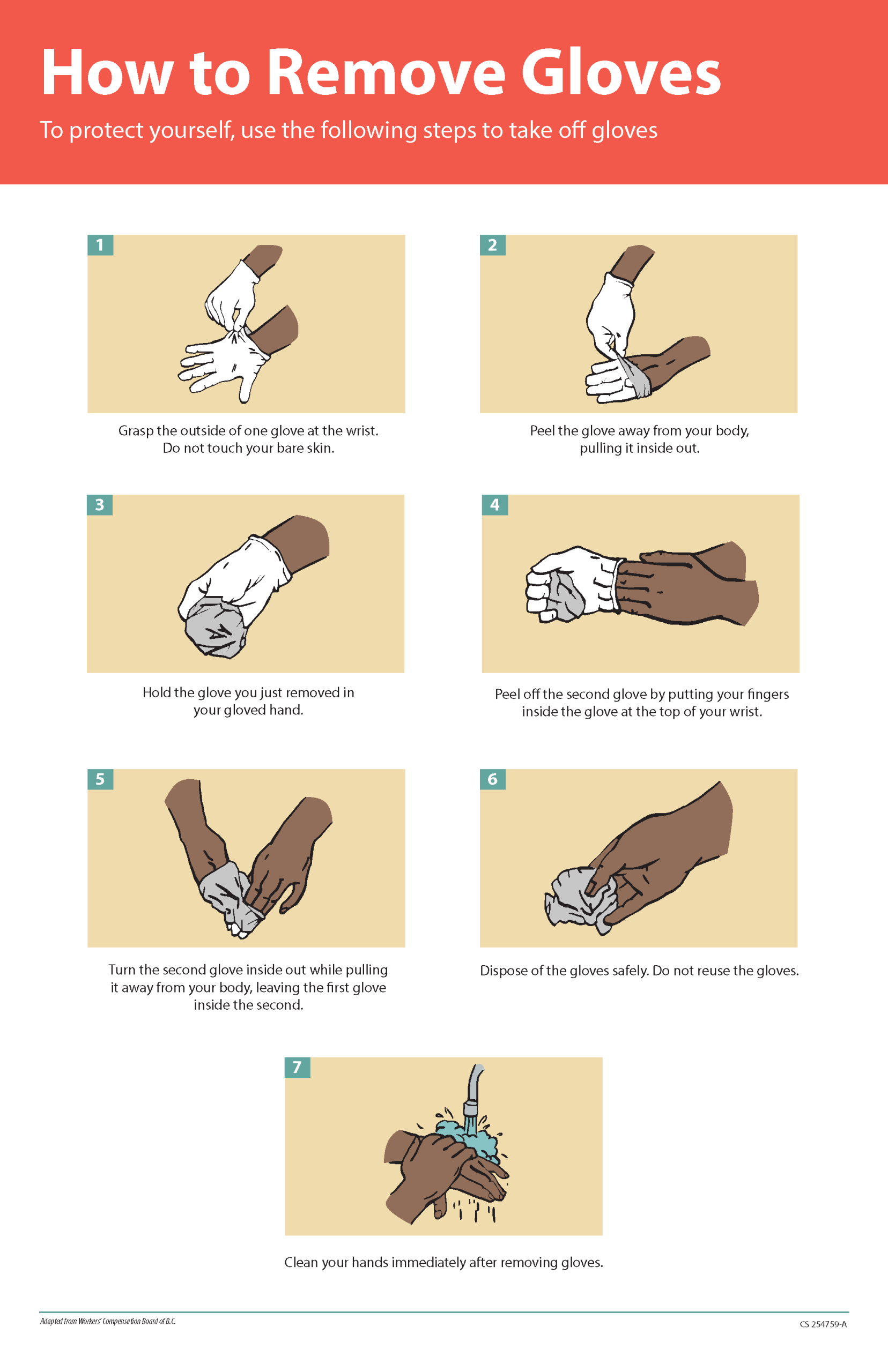

Gloves should be removed properly to prevent contamination. See Figure 4.6[19] for an illustration of properly removing gloves. Hand hygiene should be performed following glove removal to ensure the hands will not carry potentially infectious material that might have penetrated through unrecognized tears or contaminated the hands during glove removal. One method for properly removing gloves includes the following steps:

- Grasp the outside of one glove near the wrist. Do not touch your skin.

- Peel the glove away from your body, pulling it inside out.

- Hold the removed glove in your gloved hand.

- Put your fingers inside the glove at the top of your wrist and peel off the second glove.

- Turn the second glove inside out while pulling it away from your body, leaving the first glove inside the second.

- Dispose of the gloves safely. Do not reuse.

- Perform hand hygiene immediately after removing the gloves.[20]

Gowns

Isolation gowns are used to protect the health care worker’s arms and exposed body areas and to prevent contamination of their clothing with blood, body fluids, and other potentially infectious material. Isolation gowns may be disposable or washable/reusable. See Figure 4.7[21] for an image of a nurse wearing an isolation gown along with goggles and a respirator. When using standard precautions, an isolation gown is worn only if contact with blood or body fluid is anticipated. However, when contact transmission-based precautions are in place, donning of both gown and gloves upon room entry is indicated to prevent unintentional contact of clothing with contaminated environmental surfaces.

Gowns are usually the first piece of PPE to be donned. Isolation gowns should be removed before leaving the patient room to prevent possible contamination of the environment outside the patient’s room. Isolation gowns should be removed in a manner that prevents contamination of clothing or skin. The outer, “contaminated,” side of the gown is turned inward and rolled into a bundle, and then it is discarded into a designated container to contain contamination. See more information about putting on and removing PPE in the subsection below.[22]

Masks

The mucous membranes of the mouth, nose, and eyes are susceptible portals of entry for infectious agents. Masks are used to protect these sites from entry of large infectious droplets. See Figure 4.8[23] for an image of nurse wearing a surgical mask. Masks have three primary purposes in health care settings:

- Used by health care personnel to protect them from contact with infectious material from patients (e.g., respiratory secretions and sprays of blood or body fluids), consistent with standard precautions and droplet transmission precautions

- Used by health care personnel when engaged in procedures requiring sterile technique to protect patients from exposure to infectious agents potentially carried in a health care worker’s mouth or nose

- Placed on coughing patients to limit potential dissemination of infectious respiratory secretions from the patient to others in public areas (i.e., respiratory hygiene)[24]

Masks may be used in combination with goggles or a face shield to provide more complete protection for the face. Masks should not be confused with respirators used during airborne transmission-based precautions to prevent inhalation of small, aerosolized infectious droplets.[25]

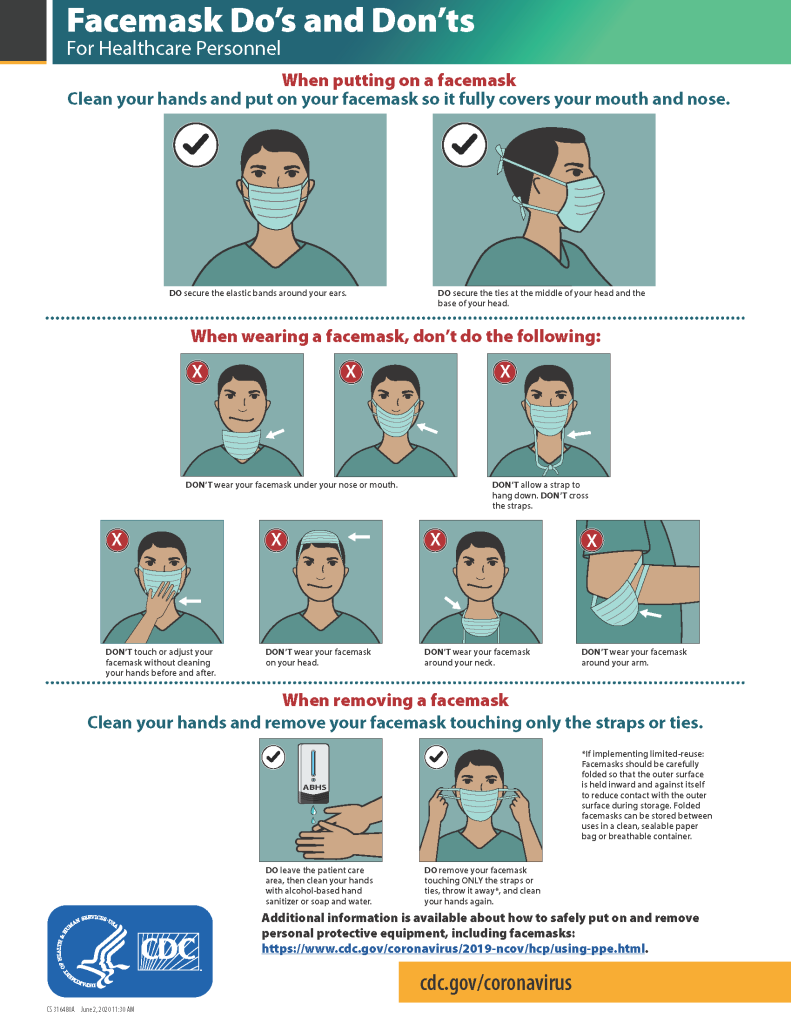

It is important to properly wear and remove masks to avoid contamination. See Figure 4.9[26] for CDC face mask recommendations for health care personnel.

Goggles/Face Shields

Eye protection chosen for specific work situations (e.g., goggles or face shields) depends upon the circumstances of exposure, other PPE used, and personal vision needs. Personal eyeglasses are not considered adequate eye protection. See Figure 4.10[27] for an image of a health care professional wearing a face shield along with a N95 respirator.

Respirators and PAPRs

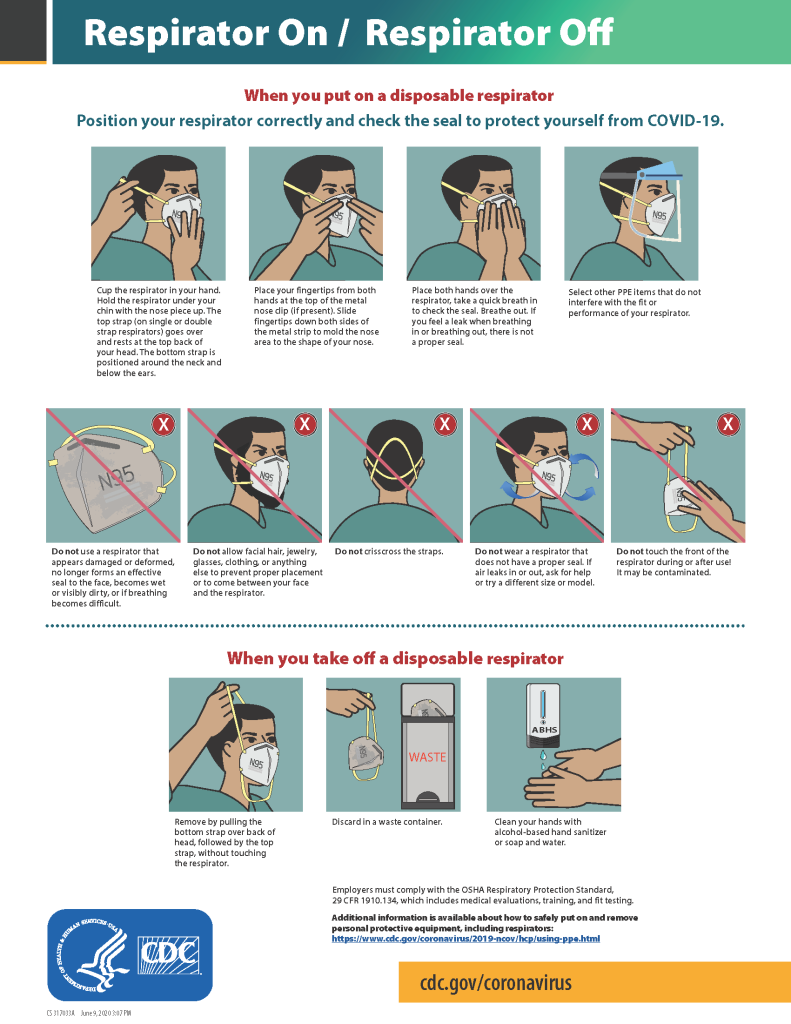

Respiratory protection used during airborne transmission precautions requires the use of special equipment. Traditionally, a fitted respirator mask with N95 or higher filtration has been worn by health care professionals to prevent inhalation of small airborne infectious particles. A user-seal check (formerly called a “fit check”) should be performed by the wearer of a respirator each time a respirator is donned to minimize air leakage around the facepiece.

A newer piece of equipment used for respiratory protection is the powered air-purifying respirator (PAPR). A PAPR is an air-purifying respirator that uses a blower to force air through filter cartridges or canisters into the breathing zone of the wearer. This process creates an air flow inside either a tight-fitting facepiece or loose-fitting hood or helmet, providing a higher level of protection against aerosolized pathogens, such as COVID-19, than a N95 respirator. See Figure 4.11[28] for an example of PAPR in use.

The CDC currently recommends N95 or higher level respirators for personnel exposed to patients with suspected or confirmed tuberculosis and other airborne diseases, especially during aerosol-generating procedures such as respiratory-tract suctioning.[29] It is important to apply, wear, and remove respirators appropriately to avoid contamination. See Figure 4.12[30] for CDC recommendations when wearing disposable respirators.

How to Put On (Don) PPE Gear

Follow agency policy for donning PPE according to transmission-based precautions. More than one donning method for putting on PPE may be acceptable. The CDC recommends the following steps for donning PPE[31]:

- Identify and gather the proper PPE to don. Ensure the gown size is correct.

- Perform hand hygiene using hand sanitizer or wash hands with soap and water.

- Put on the isolation gown. Tie all of the ties on the gown. Assistance may be needed by other health care personnel to tie back ties.

- Based on specific transmission-based precautions and agency policy, put on a mask or N95 respirator. The top strap should be placed on the crown (top) of the head, and the bottom strap should be at the base of the neck. If the mask has loops, hook them appropriately around your ears. Masks and respirators should extend under the chin, and both your mouth and nose should be protected. Perform a user-seal check each time you put on a respirator. If the respirator has a nosepiece, it should be fitted to the nose with both hands, but it should not be bent or tented. Masks typically require the nosepiece to be pinched to fit around the nose, but do not pinch the nosepiece of a respirator with one hand. Do not wear a respirator or mask under your chin or store it in the pocket of your scrubs between patients.

- Put on a face shield or goggles when indicated. When wearing an N95 respirator with eye protection, select eye protection that does not affect the fit or seal of the respirator and one that does not affect the position of the respirator. Goggles provide excellent protection for the eyes, but fogging is common. Face shields provide full-face coverage.

- Put on gloves. Gloves should cover the cuff (wrist) of the gown.

- You may now enter the patient’s room.

How to Take Off (Doff) PPE Gear

More than one doffing method for removing PPE may be acceptable. Train using your agency’s procedure, and practice until you have successfully mastered the steps to avoid contamination of yourself and others. There are established cases of nurses dying from disease transmitted during incorrect removal of PPE. Below are sample steps of doffing established by the CDC[34]:

- Remove the gloves. Ensure glove removal does not cause additional contamination of the hands. Gloves can be removed using more than one technique (e.g., glove-in-glove or bird beak).

- Remove the gown. Untie all ties (or unsnap all buttons). Some gown ties can be broken rather than untied; do so in a gentle manner and avoid a forceful movement. Reach up to the front of your shoulders and carefully pull the gown down and away from your body. Rolling the gown down is also an acceptable approach. Dispose of the gown in a trash receptacle. If it is a washable gown, place it in the specified laundry bin for PPE in the room.

- Health care personnel may now exit the patient room.

- Perform hand hygiene.

- Remove the face shield or goggles. Carefully remove the face shield or goggles by grabbing the strap and pulling upwards and away from head. Do not touch the front of the face shield or goggles.

- Remove and discard the respirator or face mask. Do not touch the front of the respirator or face mask. Remove the bottom strap by touching only the strap and bringing it carefully over the head. Grasp the top strap and bring it carefully over the head, and then pull the respirator away from the face without touching the front of the respirator. For masks, carefully untie (or unhook ties from the ears) and pull the mask away from your face without touching the front.

- Perform hand hygiene after removing the respirator/mask. If your workplace is practicing reuse, perform hand hygiene before putting it on again.

View a YouTube Video from the CDC on Putting on PPE[35]

View a YouTube Video from the CDC on Removing PPE[36]

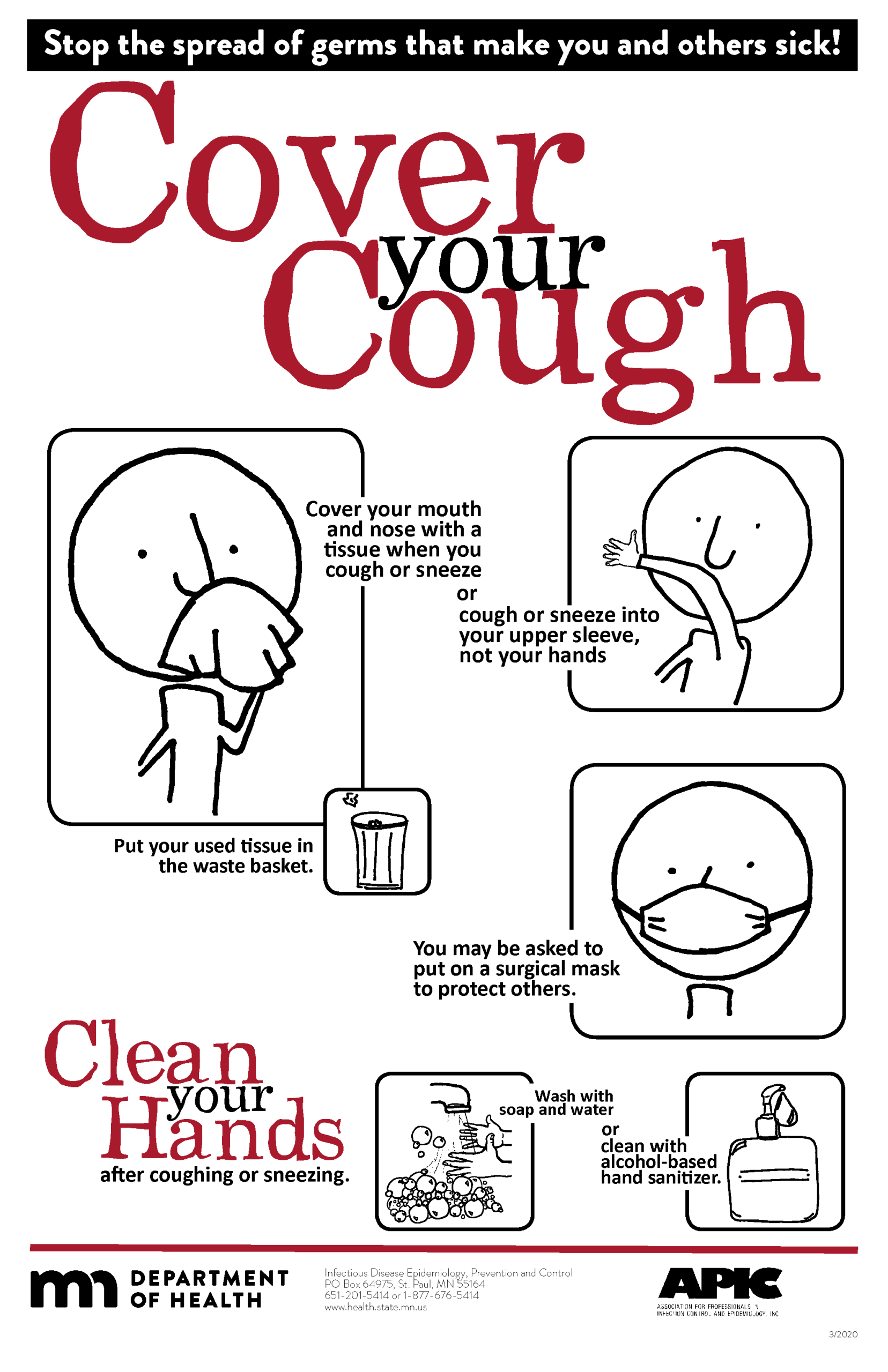

Respiratory Hygiene

Respiratory hygiene is targeted at patients, accompanying family members and friends, and health care workers with undiagnosed transmissible respiratory infections. It applies to any person with signs of illness, including cough, congestion, rhinorrhea, or increased production of respiratory secretions when entering a health care facility. See Figure 4.13[37] for an example of a “Cover Your Cough” poster used in public areas to promote respiratory hygiene. The elements of respiratory hygiene include the following:

- Education of health care facility staff, patients, and visitors

- Posted signs, in language(s) appropriate to the population served, with instructions to patients and accompanying family members or friends

- Source control measures for a coughing person (e.g., covering the mouth/nose with a tissue when coughing and prompt disposal of used tissues, or applying surgical masks on the coughing person to contain secretions)

- Hand hygiene after contact with one’s respiratory secretions

- Spatial separation, ideally greater than 3 feet, of persons with respiratory infections in common waiting areas when possible.[38]

Health care personnel are advised to wear a mask and use frequent hand hygiene when examining and caring for patients with signs and symptoms of a respiratory infection. Health care personnel who have a respiratory infection are advised to avoid direct patient contact, especially with high-risk patients. If this is not possible, then a mask should be worn while providing patient care.[39]

Environmental Measures

Routine cleaning and disinfecting surfaces in patient-care areas are part of standard precautions. The cleaning and disinfecting of all patient-care areas are important for frequently touched surfaces, especially those closest to the patient that are most likely to be contaminated (e.g., bedrails, bedside tables, commodes, doorknobs, sinks, surfaces, and equipment in close proximity to the patient).

Medical equipment and instruments/devices must also be cleaned to prevent patient-to-patient transmission of infectious agents. For example, stethoscopes should be cleaned before and after use for all patients. Patients who have transmission-based precautions should have dedicated medical equipment that remains in their room (e.g., stethoscope, blood pressure cuff, thermometer). When dedicated equipment is not possible, such as a unit-wide bedside blood glucose monitor, disinfection after each patient’s use should be performed according to agency policy.[40]

Disposal of Contaminated Waste

Medical waste requires careful disposal according to agency policy. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) has established measures for discarding regulated medical waste items to protect the workers who generate medical waste, as well as those who manage the waste from point of generation to disposal. Contaminated waste is placed in a leak-resistant biohazard bag, securely closed, and placed in a labeled, leakproof, puncture-resistant container in a storage area. Sharps containers are used to dispose of sharp items such as discarded tubes with small amounts of blood, scalpel blades, needles, and syringes.[41]

Sharps Safety

Injuries due to needles and other sharps have been associated with transmission of blood-borne pathogens (BBP), including hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and HIV to health care personnel. The prevention of sharps injuries is an essential element of standard precautions and includes measures to handle needles and other sharp devices in a manner that will prevent injury to the user and to others who may encounter the device during or after a procedure. The Bloodborne Pathogens Standard is a regulation that prescribes safeguards to protect workers against health hazards related to blood-borne pathogens. It includes work practice controls, hepatitis B vaccinations, hazard communication and training, plans for when an employee is exposed to a BBP, and recordkeeping.

When performing procedures that include needles or other sharps, dispose of these items immediately in FDA-cleared sharps disposal containers. Additionally, to prevent needlestick injuries, needles and other contaminated sharps should not be recapped. See Figure 4.14[42] for an image of a sharps disposal container. FDA-cleared sharps disposal containers are made from rigid plastic and come marked with a line that indicates when the container should be considered full, which means it’s time to dispose of the container. When a sharps disposal container is about three-quarters full, follow agency policy for proper disposal of the container.

If you are stuck by a needle or other sharps or are exposed to blood or other potentially infectious materials in your eyes, nose, mouth, or on broken skin, immediately flood the exposed area with water and clean any wound with soap and water. Report the incident immediately to your instructor or employer and seek immediate medical attention according to agency and school policy.

Textiles and Laundry

Soiled textiles, including bedding, towels, and patient or resident clothing may be contaminated with pathogenic microorganisms. However, the risk of disease transmission is negligible if they are handled, transported, and laundered in a safe manner. Follow agency policy for handling soiled laundry using standard precautions. Key principles for handling soiled laundry are as follows:

- Do not shake items or handle them in any way that may aerosolize infectious agents.

- Avoid contact of one’s body and personal clothing with the soiled items being handled.

- Place soiled items in a laundry bag or designated bin in the patient’s room before transporting to a laundry area. When laundry chutes are used, they must be maintained to minimize dispersion of aerosols from contaminated items.[43]