v. Resumes and Profiles: The College Version

You may already have a resume or a similar profile (such as LinkedIn), or you may be thinking about developing one. Usually, these resources are not required for early college studies, but you may need them for internships, work-study, or other opportunities. When it comes to an online profile, something that is a public resource, be very considerate and intentional when developing it.

Resume Overview

A resume is a summary of your education, experience, and other accomplishments. It is not simply a list of what you’ve done; it’s a showcase that presents the best you have to offer for a specific role. While most resumes have a relatively similar look and feel, there are some variations in the approach. Especially when developing your first resume or applying in a new area, you should seek help from resources such as career counselors and others with knowledge of the field. Websites can be very helpful but be sure to run your resume by others to make sure it fits the format and contains no mistakes.

A resume is a one-page summary (two, if you are a more experienced person) that generally includes the following information:

- Name and contact information

- Objective and/or summary

- Education—all degrees and relevant certifications or licenses

- While in college, you may list coursework closely related to the job to which you’re applying.

- Work or work-related experience—usually in reverse chronological order, starting with the most recent and working backward. (Some resumes are organized by subject/skills rather than chronologically.)

- Career-related/academic awards or similar accomplishments

- Specific work-related skills

While you’re in college, especially if you went into college directly after high school, you may not have formal degrees or significant work experience to share. That’s okay though!

Tailor the resume to the position for which you’re applying, and include high school academic, extracurricular, and community-based experience. These show your ability to make a positive contribution and are a good indicator of your work ethic. Later on in this chapter, we’ll discuss internships and other programs through which you can gain experience, all of which can be listed on your resume. Again, professionals and counselors can help you with this.

If you have significant experience outside of college, you should include it if it’s relatively recent, relates to the position, and/or includes transferable skills (discussed above) that can be used in the role for which you’re applying. Military service or similar experience should nearly always be included. If you had a long career with one company quite some time ago, you can summarize that in one resume entry, indicating the total years worked and the final role achieved. These are judgment calls, and again you can seek guidance from experts.

At the end of this chapter we’ve added a supplement for writing great resumes and cover letters so you have it as a reference as you prepare to market yourself!

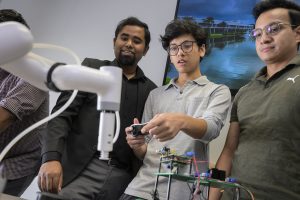

Photo by University of New Orleans

Digital Profiles

An online profile is a nearly standard component of professional job seeking and networking. LinkedIn is a networking website used by people from nearly every profession. It combines elements of resumes and portfolios with social media. Users can view, connect, communicate, post events and articles, comment, and recommend others. Employers can recruit, post jobs, and process applications. Alternatives include Jobcase, AngelList, Hired, and Nexxt. These varying sites work in similar ways, with some unique features or practices.

Some professions or industries have specific LinkedIn groups or subnetworks. Other professions or industries may have their own networking sites, to be used instead of or in addition to LinkedIn. Industry, for example, is a networking site specifically for culinary and hospitality workers.

As a college student, it might be a great idea to have a LinkedIn or related profile. It can help you make connections in a prospective field, and provide access to publications and posts on topics that interest you. Before you join and develop a public professional profile, however, keep the following in mind:

- Be professional. Write up your profile information, any summary, and job/education experience separately, check for spelling and other errors, and have someone review before posting. Be sure to be completely honest and accurate.

- Your profile isn’t a contest. As a college student, you may only have two or three items to include on your profile. That’s okay. Overly long LinkedIn profiles—like overly long resumes—aren’t effective anyway, and a college student’s can be brief.

- Add relevant experience and information as you attain it. Post internships, summer jobs, awards, or work-study experiences as you attain them. Don’t list every club or organization you’re in if it doesn’t pertain to the professional field, but include some, especially if you become head of a club or hold a competitive position, such as president or member of a performance group or sports team.

- Don’t “overconnect.” As you meet and work with people relevant to your career, it is appropriate to connect with them through LinkedIn by adding a personal note on the invite message. But don’t send connection invites to people with whom you have no relationship, or to too many people overall. Even alumni from your own school might be reluctant to connect with you unless you know them relatively well.

- Professional networking is not the same as social media. While LinkedIn has a very strong social media component, users are often annoyed by too much nonprofessional sharing (such as vacation/child pictures); aggressive commenting or arguing via comments is also frowned upon. As a student, you probably shouldn’t be commenting or posting too much at all. Use LinkedIn as a place to observe and learn. And in terms of your profile itself, keep it professional, not personal.

- LinkedIn is not a replacement for a real resume.

There’s no need to rush to build and post an online professional profile—certainly not in your freshman year. But when the time is right, it can be a useful resource for you and future employers.

Social Media and Online Activity Never Go Away

While thinking about LinkedIn and other networks, it’s a good time to remember that future employers, educational institutions, internship coordinators, and anyone else who may hire or develop a relationship with you can see most of what you’ve posted or done online. Companies are well within their rights to dig through your social media pages, and those of your friends or groups you’re part of, to learn about you. Tasteless posts, inappropriate memes, harassment, pictures or videos of high-risk behavior, and even aggressive and mean comments are all problematic. They may convince a potential employer that you’re not right for their organization. Be careful of who and what you retweet, like, and share. It’s all traceable, and it can all have consequences.

For other activities on social media, such as strong political views, activism, or opinions on controversial topics, you should use your judgment. Most strong organizations will not be dissuaded from working with you because you’re passionate about something within the realm of civility, but any posts or descriptions that seem insensitive to groups of people can be taken as a reason not to hire you. While you have freedom of speech with regard to the government, that freedom does not extend to private companies’ decisions on whether to hire you. Even public institutions, such as universities and government agencies, can reject you for unlawful activity (including threats or harassment) revealed online; they can also reject you if you frequently post opinions that conflict with the expectations of both your employer and the people/organizations they serve.

With those cautions in mind, it’s important to remember that anything on your social media or professional network profiles related to federally protected aspects of your identity—race, national origin, color, disability, veteran status, parental/pregnancy status, religion, gender, age, or genetic information (including family medical history)—cannot be held against you in hiring decisions.

Building Your Portfolio

Future employers or educational institutions may want to see the work you’ve done during school. Also, you may need to recall projects or papers you wrote to remember details about your studies. Your portfolio can be one of your most important resources.

Photo by University of New Orleans

Portfolio components vary according to field. Business students should save projects, simulations, case studies, and any mock companies or competitions they worked on. Occupational therapy students may have patient thank-you letters, summaries of volunteer activity, and completed patient paperwork (identities removed). Education majors will likely have lesson plans, student teaching materials, sample projects they created, and papers or research related to their specialization.

Other items to include a portfolio:

- Evidence of any workshops or special classes you attended. Include a certificate, registration letter, or something else indicating you attended/completed it.

- Evidence of volunteer work, including a write-up of your experience and how it impacted you.

- Related experience and work products from your time prior to college.

- Materials associated with career-related talks, performances, debates, or competitions that you delivered or took part in.

- Products, projects, or experiences developed in internships, fieldwork, clinicals, or other experiences (see below).

- Evidence of “universal” workplace skills such as computer abilities or communication, or specialized abilities such as computation/number crunching.

A portfolio is neither a scrapbook nor an Instagram story. No need to fill it with pictures of your college experience unless those pictures directly relate to your career. If you’re studying theology and ran a religious camp, include a picture. If you’re studying theology and worked in a food store, leave it out.

Certain disciplines, such as graphic design, music, computer science, and other technologies, may have more specific portfolio requirements and desired styles. You’ll likely learn about that in the course of your studies but be sure to proactively inquire about these needs or seek examples. Early in your college career, you should be most focused on gathering components for your portfolio, not formalizing it for display or sharing.