6 Organization

Do you ever begin writing and think “this all makes sense in my head, but I can’t seem to get it right on paper?” This phenomenon affects almost all writers at some point in their careers, and it is somewhat easier to explain why it happens than you might expect.

Thoughts, opinions, and arguments have a lot of space to expand in our minds. Sometimes, we can associate ideas without even realizing that we are making a connection between them. While everyone thinks a little differently, the process of forming an argument in the mind can be similar to the creation of a 3-D model of the planets in the universe, where lots of ideas and evidence circle around a main point but the force holding them together is somewhat invisible (like gravity). All the same, people have a reason for believing what they do, and those connections are vital infrastructure even if they seem hard to define.

The issue occurs when we are asked to take that 3-D thought model, or other expansive thought processes, and flatten them onto a page. Whereas before, recursive or unstated connections between ideas still resulted in a tangible outcome–an argument or belief–now, on paper, these connections need to be explained in detail and in a logical progression in order to make a clear claim. In order to write, we must find a way to transition from our personal thinking patterns to a linear model of conveying information.

That’s where organization comes in. Organized writing is not something that magically occurs. It is something that is created over time–often through review and revision–until we successfully transfer what’s in our heads to the page. Organized writing not only helps our readers understand our arguments, but once we understand and master certain forms of organization, it can also help us overcome the initial difficulty of writing in the first place.

In this chapter, we will explore different types of organizational schema and strategies that can help you 1) understand what your reader expects of your writing, and 2) use those expectations to structure your thoughts into a linear argument.

The Importance of Organization

Humans like routine, and some even expect it so much that deviation from the routine can throw off an entire day. One area where we all expect routine is in an essay. However, in all writing modes, not just in an essay, there is some kind of organization pattern, just as there is in every architectural structure.

The routine, or organization, of a piece creates a framework that guides the reader through your excellent ideas. Of course, you can find examples of writers who twist their writing in unexpected ways, but those are exceptions that are difficult to pull off effectively. Additionally, you often find them in the creative modes, rather than the research-like modes. In general, you’ll find using an accepted organizational format not only useful for the reader, but satisfying for you as the structure will lend strength to your ideas.

Why is organization important?

- Readers expect it.

- It helps make your ideas clearer.

- It shows you’re credible; you know how to organize, so you know what you’re

- doing.

- It helps the flow of your writing and removes reading “stumbling blocks.”

Getting Started with Organization

So, how do you get started? First, consider the overall structure of any piece of writing:

- Introduction

- Body paragraphs

- Conclusion

That is the basic idea, but let’s look at organization more carefully, using the example of an essay as our mode. Keep in mind as you go through this section that if we were writing a novel, or a movie review, or a manual for work, or an epic poem, there would be different expectations, in many ways. For the most part, however, the organizational ideas below go for all modes and genres of writing.

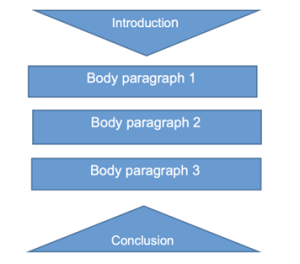

The most basic essay format is the five-paragraph essay. It looks like this:

Note

Note that the introduction is an inverted triangle because traditionally, introductions begin broadly and move to more specific information, ending with the very specific thesis statement. The conclusion, then, goes from the specific essay idea to broader generalizations about the topic.

You may have learned about the five paragraph essay in school before, and you might be comfortable with it, too. That’s great! Now, it’s time to expand on this structure to create essays of more than five paragraphs. Some essays, like essay questions in a history exam, might only require two paragraphs, while a research paper might require twenty paragraphs. In general, though, all essays will follow the introduction, body, conclusion structure, but introductions and conclusions may be more than one paragraph, and you may have more than three body paragraphs.

Ways to Organize Ideas

You have several options for organizing your ideas: chronological order, spatial order, or order of importance.

Chronological Order

Chronological, or time, order is used when relating events in which time plays a crucial role. It’s the easiest of the organizational structures because it’s one we’ve used as humans since we started telling each other stories: “Once upon a time…” It’s used all the time in the working world, too. For example, in healthcare, charting will often use chronological order to explain when certain events happened. This type of structure is great to use when time is of the essence. The same is true for a police report, to use another example.

If it matters when certain events happened or if you’re directing a reader how to do something, putting things in chronological order makes sense. For example, you might write an essay about Google. If you’re talking about how it became the most popular search engine, you would utilize chronological order to describe its ascent to domination.

Another example would be a biography. If you’re writing about Frederick Douglass, for example, a chronological outline might look something like this:

- Early life

- Parents

- Separation from mother

- Teenage years

- Learning to read

- Tutoring other slaves

- Punishment

- Escape from slavery

- Unsuccessful attempt

- Successful escape

- Free years

- Marriage

- Work as an abolitionist and preacher

Spatial Order

Spatial order, or space order, is often used when you’re describing. This type of order is also easy because when you deploy it, you act like a video camera: describing from right to left or vice versa, or from the top to the bottom or vice-versa. In the working world, civil engineers, for example, would find spatial order to be extremely important when looking at road design plans. Sometimes, description is the major role of an essay, but more frequently, you’ll use description within a single paragraph and will then consider spatial order for that segment only. An example might be describing a treehouse you had as a child, or describing the scene of an accident. An outline for an essay on this topic using spatial order might look like this:

- Before I get to the scene

- Walking down the street

- Passing people

- A dog barks viciously

- Hear the sirens

- Turning the corner

- Smell the fire

- Hear shouting

- Walking down the street

- Seeing the scene from afar

- Three cars

- One is halfway up a light pole

- Another is jammed up behind the first

- A third has t-boned the second

- Emergency vehicles

- Crowd of people

- Three cars

- Getting close up to the scene

- People on stretchers

- Firefighters putting out blaze

- A woman screaming

- An elderly woman’s dismissive comments

Order of Importance

Now, order of importance is the most common organizational structure, but it can be tricky. You can look at it in several ways:

- General to specific (commonly called deduction): Moving from general ideas to more specific ideas

- Specific to general (commonly called induction): Moving from specific ideas to more general ideas

- Most to least critical: Making your strongest point first and then bringing up less critical ideas

- Least to most critical: Bringing up less critical points early on to build up into the most important point of all

How about an example? Let’s say you want to discuss the benefits of long-distance running. You might have the following points:

- Increases strength and cardiovascular health

- Encourages weight loss

- Excellent for stress relief

- Creates a state of “flow”

- Promotes self-esteem though setting and achieving goals

How would you organize these points using order of importance? It is, of course, a matter of judgment. Which of these points is most important to you as the writer and, even more importantly, to your audience?

Let’s say your audience is first-year college student women who have never run before and want to avoid the “Freshman Fifteen.” You might want to hit them with the most important points first, to catch their attention, and then move to the other benefits, like this:

- Encourages weight loss

- Increases strength and cardiovascular health

- Excellent for stress relief

- Promotes self-esteem though setting and achieving goals

- Creates a state of “flow”

If your audience is middle-aged people who need to unwind from their days in a healthy way, it might make more sense to start with the less “important,” or more obvious to that audience, points and then build to the more compelling points that will convince them to give it a try:

- Encourages weight loss

- Increases strength and cardiovascular health

- Promotes self-esteem though setting and achieving goals

- Creates a state of “flow”

- Excellent for stress relief

An Example of Ways to Organize Persuasive Writing

Audience is critical when deciding on an organizational structure. To look at this topic of running from a slightly different perspective, what if you wanted to write about the reasons why running is difficult? What if your audience included mostly personal trainers? You might organize from the specific ideas to the more general ideas.

Specific ideas:

- The distance aspect is threatening to new runners

- Running as an exercise can be punishing on the body

- Newer runners don’t know about training regimens

General idea:

- Create a specific training program that is accessible and easy on the body to help gain strength and endurance

If you happen to be a personal trainer or you know a lot about running and your audience is middle-aged runners who have started and quit running programs over and over, you might go from the more general ideas to the more specific ideas.

General ideas:

- Safety is key when you begin exercise

- Use a running training program that starts slowly help gain strength and endurance

Specific ideas:

- Newer runners have to build up their distance over time

- Starting slow is important to avoid punishing the body

- There are various training regimens that can work

Considerations When Organizing

Organization is related to the mode of writing you choose. Sometimes, like using spatial order for descriptive writing, the type of writing you’re doing (mode) will determine organizational structure. One mode that requires strict adherence to organization is compare and contrast. Let’s look at this mode now as an example.

Let’s say you’re comparing four wheel drive and all-wheel drive vehicles. The audience is parents with young kids who have just moved to Minnesota from a southern state. You need to come up with points of comparison that are useful for that audience, such as:

- Cost of the vehicle

- Reliability over time

- Gas mileage

- Traction on the road

Based on this audience and their foremost desire for safety on the treacherous winter roads, you might want to use a general order of importance to get your points of comparison in order, going from the most important point to the lesser points:

- Traction on the road

- Reliability over time

- Cost of the vehicle

- Gas mileage

Once you’ve decided on the order of your points of comparison, you have two choices when it comes time to organize the whole essay: whole to whole or point by point.

With whole to whole, you talk about Topic One and then Topic Two. An outline might look like this:

Four Wheel Drive Vehicle

- Traction on the road

- Reliability over time

- Cost of the vehicle

- Gas mileage

All-Wheel Drive Vehicle

- Traction on the road

- Reliability over time

- Cost of the vehicle

- Gas mileage

Note

The order of the points of comparison is the same for each type of vehicle.

With point by point, those points of comparison direct an alternating discussion of both types of vehicles concurrently:

Traction on the road

- Four wheel drive

- All-wheel drive

Reliability over time

- Four wheel drive

- All-wheel Drive

Cost of the vehicle

- Four wheel drive

- All-wheel drive

Gas mileage

- Four wheel drive

- All-wheel drive

Note

For each point of comparison, you would talk about four wheel drive vehicles first, and then move to the all-wheel drive vehicles.

Pro Tip

The Student Success Center can help you think about the organization and structure of your writing. You can reach out for their help by email (success[at]lsus.edu).

Cause and effect will lend itself better to induction and deduction. Classification will be a “most important to least important” (or vice-versa) situation.

Again, what organizational structure do you choose? It depends on your topic and its mode, but ultimately, knowing what the audience expectations are for your piece of writing will help you make your decision.

Organization Between and Within Paragraphs

Now that you’ve decided how you’re going to organize your essay as a whole, you’re going to start working on getting your points on the page. How are you going to make sure your ideas flow, both within your paragraphs and when moving from paragraph to paragraph? First, note that just as an essay starts with an introduction, moves into the body, and then has a conclusion, paragraphs reflect that same structure:

- Topic sentence

- Body

- Concluding sentence

The topic sentence, like the thesis statement in an essay, gives an overview of the paragraph. The body sentences support the topic sentence with transitions, working within them to help the ideas flow. Then the concluding sentence helps wrap up ideas and/or transition into the paragraph that follows. Consider the following paragraph from The Atlantic article “Why Do Humans Talk to Animals if They Can’t Understand?” by Arianna Rebolini. The bolded words act as transitions within the paragraph:

It’s no stretch to suppose that a person with few or no friends would treat a pet more like a human friend. (topic sentence) Perhaps, too, people speak to their pets because they like to believe the animals understand, and perhaps people like to believe they understand because the alternative is kind of scary. To share a home with a living being whose mind you can’t understand and whose actions you can’t anticipate is to live in a state of unpredictability and disconnectedness. So people imagine a mind that understands, and talk to it. (concluding sentence)[2]

Just like in an essay, you can consider using any of the major organizational methods (order of importance, chronological order, etc.) to guide the ideas of each paragraph. Another good habit is to notice the way things are organized in texts you read. You can get good ideas for how to organize your own texts from other well-organized texts.

Writing Introductions, Conclusions, and Titles

Writing an Introduction

“A long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away…”

Does this ring a bell? These are the opening words to every narrative in the massive, culture-bending Star Wars franchise. Your introductions don’t need to be as earth-shattering, but they do need to do the following:

- Grab the reader’s attention

- Give a sense of the direction of ideas in the essay

- Set up what the writing will be like in the essay (super formal, more informal, etc.)

No big deal, right? Actually, it can feel like a HUGE deal, and writing the introduction can be so scary for some writers that it stops any forward progress. That being the case, here are the first two rules for writing introductions:

Rule Number One: If you don’t have ideas for the introduction, skip it!

No, don’t skip it altogether—you need to have one—but if it’s freaking you out and stopping you from getting going on your essay, start working with your body paragraphs first. Sometimes you need to play with the essay ideas for a while before an idea for the introduction alights on your shoulder and demands your attention.

Of course, sometimes ideas aren’t that cooperative and you need to work at pulling them out. Have you written the rest of the essay and now you are considering the virtues of skipping writing an introduction altogether rather than going through the torture of having to figure it out? First, relax. Don’t take it so seriously.

Rule Number Two: Consider audience!

This brings us to the second rule about introductions. Ask yourself: What will get my audience’s attention? Always consider the audience’s needs, interests, and desires. If your audience is similar to you in any way, fabulous. Ask yourself: What would get my attention? Write an introduction that amuses or fascinates you. After all, if you’re genuinely delighted, that could rub off on the reader.

It might help if you had some ideas about the types of introductions out there:

- Thesis statement

- Anecdote

- Asking questions

- A contradiction

- Starting in the middle

Thesis statement introductions are for the traditionalists. They also often work well in professional writing. They are typical in formal essays where it’s important to start broad to help create context for a topic before narrowing it in to land at the specific point of the essay, in the thesis statement, at the end of the introductory paragraph. Sometimes formal academic argument papers even start with the thesis statement (underlined), as in this example:

Parents are heroes because they work hard to show their children the difference between right and wrong, they teach their children compassion, and they help them to grow into stable, loving adults. Parents act as guides for their kids while allowing them to make mistakes, listening to them when their kids need to talk, pushing them along when they’re too shy to move on their own, and cheering the loudest when their kids achieve their dreams. It’s no easy task to be the steady, moral compass that kids need, as parents are people too, and people make mistakes. As a species, though, we manage more often than not to raise well-adjusted kids who turn into hardworking adults, giving us hope for the future.

As you can see, it’s a pretty generic introduction, but it firmly orients the reader into the topic.

Let’s say you want to stretch your creativity a bit, though. You might try an anecdotal introduction, where you tell a brief but complete story (real or fictional). This type of intro uses narration to catch the reader’s attention. Here’s an example of that using the same topic and thesis statement (underlined) as above:

When my brother was little, he used to get into all sorts of trouble. Because he was just so curious about everything, his desire to check things out often overrode his good sense. This finally got the best of him when he was nine and got stuck in a tree. He climbed up there to look into a bird’s nest, and we found him after he started yelling for us. He was twenty feet up there, and before my mom and I knew what was happening, my dad jumped up and started climbing, which was amazing because my father isn’t too fond of heights. He got up to Jason and then helped him down, showing him where to put his hands and feet. When they were both safely on the ground, my parents scolded Jason while simultaneously hugging him. He was still terrified, and suddenly, I could see how terrified my dad was, too. I never forgot that moment, and I also came to a realization. Parents aren’t just heroes because they will put their lives on the line for their kids. Parents are heroes because they work hard to show their children the difference between right and wrong, they teach their children compassion, and they help them to grow into stable, loving adults.

This strategy is great to try because it gives a specific example of your topic, and it’s human nature to enjoy hearing stories. The reader won’t be able to help being pulled into your essay when you use narration.

Another strategy writers employ when writing introductions is asking a question or questions to catch the reader’s attention. You might have heard the adage, “There are no dumb questions, only dumb answers.” While that’s often true, when it comes to introductions, you need to be smart about the types of questions you ask, always keeping your audience in mind:

- DON’T ask yes or no questions.

- DON’T ask questions that will cause the reader to tune out.

- DO ask questions that get the reader thinking in the direction you’re planning on going in within your essay.

Here’s an example of a question that will stop your reader in his or her tracks:

Have you ever wondered about how Einstein’s String Theory applies to old growth forests?

Why is this a bad question? Simple: what if the reader answers that and says “Uh…no.”

You’ve just lost the reader.

Instead, consider your audience: what questions might they actually have about your topic? For example:

When you were a kid, who were your heroes? Was it Luke Skywalker? The President of the United States? An astronaut? A firefighter? Heroes come from all walks of life…

This series of questions begins with an open-ended question that frames the topic (childhood heroes) and gets readers thinking, but not too much—the follow-up questions keep readers from floating off into la-la land with their own ideas.

Another strategy that can work well is considering the contradictions in your topic, playing Devil’s Advocate, and bringing them up right away in the introduction. When it comes to your topic, what clichés are out there about it? What misunderstandings do people have? Those ideas can make for a great introduction. For example:

When kids think about heroes, they often think about Superman or Spiderman in all of their comic book glory. These superheroes fight the bad guys, restoring order in the chaos that the villains create in the comics. They always win in the end because they are the good ones and because they have amazing abilities. What kid hasn’t thought about how cool it would be to have super powers? What kids often miss, however, and don’t understand until they’re older, is that their parents are the real superheroes in their lives. The super powers that parents have may not be bionic vision or super strength, but they have powers that are much more important. Parents are heroes because they work hard to show their children the difference between right and wrong, they teach their children compassion, and they help them to grow into stable, loving adults.

Note

In this sample, there’s a contradiction: the cliché idea of heroes as cartoon superheroes, but there’s also a rhetorical question. Often, strategies for writing introductions can be combined to great effect.

Finally, an introductory strategy worth noting is similar to an anecdote, but instead of starting at the beginning of a story, you start in the middle of the action. For example, instead of setting the scene by starting in the cafeteria on a normal school day, you would start like this:

A wad of spaghetti smacked the side of my face, and one of the noodles ricocheted off my cheek and swung into my mouth. I nearly inhaled it, but before I started choking, I managed to fling a handful of fries in Jose’s direction. I saw Amy running over to dump her milkshake on Anthony’s head before I ducked under the table. It was full-on pandemonium in the cafeteria, boys versus girls, a spark of rage finally igniting after weeks of classroom tension.

Starting an essay right in the middle of action immediately piques the reader’s interest and creates a tension that can, admittedly, be difficult to come down from, but it sure makes for an exciting start.

These strategies can serve to enliven your essay topic, not just for the reader, but for you. When you can build an introduction that you can be proud of, it can give you creative ideas for the rest of your piece. Consider trying several different strategies for your introduction and choose what works best. Perhaps even combine a few to customize. It’s also worth noting that, though introductions are traditionally one paragraph with the thesis statement as the last sentence, there’s nothing which says that an introduction can’t be more than one paragraph. It’s all about what’s going to work for your topic and for your audience.

Writing a Conclusion

Let’s be honest: when you’ve spent so much time working out the ideas of your essay, organizing them, and writing an awesome, eye-catching introduction, by the time you get to the conclusion, you might have run out of steam. It can feel impossible to maintain the creative momentum through the most boring of paragraphs: the conclusion. So what do writers do? Easy: they start by writing, “In conclusion…” and sum up what the reader just finished reading.

If that feels off to you, good–it should. Unless you’ve written a long essay, a summary-style conclusion isn’t appropriate and can even be insulting to the reader: why would you think readers need to be reminded of what they just read? Have more faith in them and in your own writing. If you’ve done your job in the essay, your ideas will be etched in readers’ brains.

You still need to have a conclusion, though. So what’s a conscientious writer to do?

The goal of a conclusion is to leave the reader with the final impression of your take on the topic. You don’t need to try to have the final, be-all, end-all word on the topic, case closed, no more discussion. Readers will reject this type of language. Again, don’t worry about summarizing what you’ve just written.

Think about a boring conclusion being like the end of a class period. Your classmates are putting their books away, packing their bags, glancing at their phones—their minds are already floating away from the topics in the class. An effective teacher will keep student attention until she is ready to dismiss the class, and an effective conclusion will not just keep the reader’s attention until the end but will make them want to go back to the beginning and re-read—to see what they might have missed.

Types of Conclusions

Mirroring the Introduction

The easiest way to write a conclusion, especially after you’ve written a stellar introduction, is to mirror the introduction. So, if you’ve started by setting the scene in the cafeteria mid-food fight, go back to the cafeteria in the conclusion, perhaps just as the fight is over and it’s dawned on all the kids that this food-fight was a bad idea. If you spent your introduction bringing up a contradiction and dispelling it, allude to that contradiction again in your conclusion. If you asked a question in the introduction, you’d better be sure to answer it in the conclusion.

Predicting the Future

Mirroring is the easiest way of thinking about an appropriate concluding strategy. You might also consider predicting the future implications of your arguments. Let’s say you’re arguing for increased sales taxes to help improve your city’s crumbling roads in your essay. In your conclusion, paint a picture of what the future roads would look like (or feel like when driving on them) if you got your way. This idyllic, concrete scene would remain in readers’ minds, increasing the chances that they’ll remember your point of view.

Humor

Another option that helps to endear you one more time to the reader is ending with something funny or catchy. When readers feel good because you utilized the strategy of a humorous conclusion, they’ll remember both that feeling and your take on the topic. You don’t need to be a comedian to be funny, either. You can utilize jokes made in popular culture to make your reader smile: from the classic “Where’s the beef?” catchphrase the fast-food chain Wendy’s utilized in the 80’s to the more current “double rainbow” YouTube video to the most cutting-edge memes, these jokes can be utilized for an impactful conclusion. The key (and warning!), however, is to consider your audience. Choose something that will amuse your audience, because although you don’t need to be a comedian to write a humorous conclusion, like a comedian, if the joke falls flat, you’ll leave readers with crickets chirping and the kind of awkward silence that all comedians face one time or another.

Memorable Phrases

Another great option is one encouraged by the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle in his books on Rhetoric: use a maxim, or proverb. These are like folk-wisdom, or quotes by famous people who really know how to turn a phrase.

For example, in writing a paper arguing about nursery rhymes and the gender roles in them, you could end by quoting a portion of the ending nursery rhyme: Snip, snap, snout, This tale’s told out.

Of course, this strategy could fail, too, by hitting the wrong note or not being quite on-topic. This is where an extra pair of eyes (or two or three) helps: test your conclusion out on others before you call it your final draft.

Writing a Gripping Title

Some people have no problem coming up with titles for their essays. The struggle is NOT real for them, and they don’t understand why the rest of us have difficulties with this relatively small part of the essay, at least small in terms of the number of words. These same people should probably go out and play the lottery because they’re lucky. For the rest of us, however, we need to work at it.

Titles are scary because they’re short, yet they must do a lot of work: they state the topic, a direction for the topic, and grab attention. You might note that these are basically the same tasks of the introduction, but at least with that, you have a whole paragraph. The same can’t be said with a title (unless you’re going for something absurd, which your supervisor or writing teacher will likely not appreciate).

Yes, writing a title requires some creativity. In this case, though, there’s a strategy you can use to think about title creation.

Step One: Write down your topic.

Hank Aaron, baseball legend

Step Two: Think about the points you’re going to make in the essay about your topic.

This is a major research paper, so it’s long. I’m going to write about his baseball life, his early life, and his passions outside of baseball (civil rights)

Step Three: Brainstorm a list of ideas, clichés, and associations dealing with your topic.

Baseball, take me out to the ball game, grand slam, double-header, triple play, seventh-inning stretch, peanuts and Cracker Jack, “Juuuust a bit outside,” major league, home run, homers, crack of the bat, Negro League, Milwaukee Brewers, The Hammer (his nickname), swing and miss…

Step Four: Put the ideas together in interesting ways to create title options.

- Hank Aaron Hammers It Home

- Triple Play: The Life, Love, and Career of Hank Aaron

- From Mobile to the Majors: Hank Aaron’s Success Story

- …and so on.

Note

The second two title options above utilize a colon. These are titles with subtitles, sometimes called a two-part title. The first part, before the colon, is the eye-catcher. The second part gives a direction for the essay. A subtitle is an opportunity you can exercise to get more words for your title

Let’s say you’re going to write a persuasive essay about the importance of attending class. You can think of different titles based on different strategies:

- Description of your essay

- How to be a Successful College Student

- Rhetorical question

- To Attend or Not to Attend?

- Mode of writing title

- Go to Class!

- Two-part title

- Attendance: The Key to Acing College

- Lifting a great phrase from your essay title

- Be There: Attending Class to Ace College

Taking into consideration all of the strategies presented in this chapter will help you write an organized essay that will grab your audience’s attention.

Listen to the Audio Chapter

Media Attributions

- 5 paragraph essay structure © Textbook Authors is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- https://oer.galileo.usg.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1007&context=english- textbooks ↵

- Enter your footnote content here.Rebolini, Arianna “Why do humans talk to animals if they can’t understand?” The Atlantic 18 August 2017. https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2017/08/talking-to-pets/537225/ ↵