Chapter 1: Communication Foundations

Sydney Epps

Chapter Learning Objectives

- Distinguish between the nature of English and Communications courses.

- Explain the importance of studying Communications.

- Identify communication-related skills and personal qualities favored by employers.

- Consider how communication skills will ensure your future professional success.

- Recognize that the quality of your communication represents the quality of your company.

- Distinguish between personal and professional uses of communications technology in ways that ensure career success and personal health.

- Select and use common, basic information technology tools to support communication.

- Illustrate the communication process to explain the end goal of communication.

- Troubleshoot communication errors by breaking down the communication process into its component parts.

- Reframe information gained from spoken messages in ways that show accurate analysis and comprehension.

Let’s begin by answering the question that is probably on the mind of anyone enrolled in an introductory English Communications course. Why are you here? It is unlikely you chose this course out of your natural enthusiasm for English classes. It’s because it is a requirement to advance in the program and graduate.

So why would the program administrators require you to take this course? You need sharp communication skills to be able to apply the core skills you are learning in your other courses in the program. This textbook’s first section expands on this so that you can proceed through this course in the right frame of mind. None of your courses make sense unless you realize that communications skills are a necessary key to thriving in this global environment, particularly through economic volatility.

- 1.1: Why Communications?

- 1.2: Communicating in the Digital Age

- 1.3: The Communication Process

- 1.4: Troubleshooting Miscommunication

1.1: Why Communications?

Section 1.1 Learning Objectives

- Distinguish between the nature of English and Communications courses.

- Explain the importance of studying Communications.

- 1.1.1: Communications vs. English Courses

- 1.1.2: Communication Skills Desired by Employers

- 1.1.3: A Diverse Skill Set Featuring Communications Is Key to Survival

- 1.1.4: Communication Represents You and Your Employer

1.1.1: Communications vs. English Courses

Whether students enter their first-year college Communications courses right out of high school or with years of work experience behind them, they often fear being doomed to repeat their high school English class, reading Shakespeare and writing essays. Welcome relief comes when they discover that a course in Communications has nothing to do with either of those things. Why should it when no one in the modern workplace speaks in a Shakespearean dialect or writes expository essays? If not High School English 2.0, what is Communications about?

For our purposes, Communications (with a capital C and ending with an s) is essentially the practice of interacting with others in the workplace and other professional contexts. Every job—from A to Z, accountant to zoologist—involves dealing with a variety of people all day long. You may deal with clients, managers, coworkers, stakeholders (such as investors or suppliers), professional organizations, a union, investors, the public, media, students, and more, depending on the nature of the job.

When dealing with each of those audiences, we adjust the way we communicate according to well-known conventions. You would not talk to a customer or client the same way you would a long-time friendly coworker; depending on what kind of relationship you have with your manager, you probably would not speak or write to them in the same way you would either of the others. Learning those communication conventions is certainly easier and more useful than learning how to interpret a four-hundred-year-old play. If we communicate effectively—that is, clearly, concisely, coherently, correctly, and convincingly—by following those conventions, we can do a better job of applying our core technical skills, whether they be in sales, the skilled trades, the service industry, health care, office management, the government, the arts, and so on.

A course in Communications brings your existing communication skills up to a professional level by focusing on how to follow conventions for interacting with those various audiences in a variety of channels—whether they be speaking in person or by phone, email, text, or emojis, for instance. That we do not generally communicate by emojis with clients or managers (unless they tell us that they prefer it), for instance, is a convention that does not occur naturally to some. Indeed, it may come as a surprise to some that you’d risk embarrassing yourself and permanently undermining your credibility if you added emojis to a message sent to a manager or client. Because we are not born with an instinct for staying within the bounds of respectable communication, the channel conventions must be learned and practiced.

Some will approach this course with years of professional experience behind them and will appreciate that the communication aspect of any job is easy to underestimate. They will also appreciate that not abiding by those well-established communication conventions—by going rogue and freestyling the way you communicate—usually brings embarrassment and failure. To the audiences you deal with in the workplace, how well you communicate determines your level of professionalism. It’s like your style of dress: a well-written email has the same effect as a nice suit worn in an office or a clean uniform worn by a service worker—it suggests detail-oriented competence. Major writing errors are like big stains down the front of that suit or revealing rips in that uniform—they make you look sloppy, foolish, and unreliable. Just as we spent decades getting to where we are now as communicators in whatever situation we find ourselves, we need a college course to iron out the wrinkles of our communication skills for the better workplaces we aspire to—what we go to a vocational college for—in ways that our previous work experience and high school English classes did not.

This is not to say that your high school English classes were useless, though few can claim that they prepared you adequately for the modern workplace. Arguably the movement away from English fundamentals (grammar, punctuation, spelling, style, mechanics, etc.) in high school does a disservice to students when they get into their careers. There they soon realize that stakeholders—customers, managers, coworkers, etc.—tend to judge the quality of a person’s general competence by the quality of their writing (if that’s all they have to go on) and speaking. The topic of Communications, then, includes aspects of the traditional English class curriculum, at least in terms of the basics of English writing. But the emphasis always returns to what is practical and necessary for succeeding in the modern workplace—wherever that is—not simply what is “good for you” in the abstract just because someone says it is.

If you feel that you are a weak writer but an excellent speaker or vice versa, rest assured that weaknesses and strengths in different areas of the communication spectrum do not necessarily mean that you will always be good or bad at communication in general. Weaknesses can and should be improved upon, as well as strengths built upon. It’s important to recognize that we have more communication channels available to us than ever before, which means that the communication spectrum—from oral to written to nonverbal channels—is broader than ever. Competence across that spectrum is no longer just a “nice to have” asset sought by employers but essential to career success.

Key Takeaway

By teaching you the communications conventions for dealing with a variety of stakeholders, a course in Communications has different goals from your high school English course and is a vitally important step toward professionalizing you for entry or re-entry into the workforce.

Exercise

List your communication strengths and weaknesses. Next, explain what you hope to get out of this Communications course now that you know a little more about what it involves. Before you answer, however, read ahead through the rest of this chapter to get a further sense of why this course is so vital to your career success.

1.1.2: Communication Skills Desired by Employers

Section 1.1.2 Learning Objectives

- Identify communication-related skills and personal qualities favored by employers.

If there’s a shorthand reason for why you need communication skills to complement your technical skills, it’s that you do not get paid without them. You need communication and “soft” skills to get work and keep working so that people continue to want to employ you to apply your core technical skills. A diverse skill set that includes communication is really the key to survival in the modern workforce, and hiring trends bear this out.

In an annual Graduate Management Admission Council Corporate Recruiters Survey of the skills candidates need to enter and grow in the 21st-century workplace, “[c]ommunication skills topped the list, followed in order by teamwork skills, technical skills, leadership skills, and managerial skills” (GMAC Research Team, 2020). Employers specifically want employees to know how to:

- Read and understand information presented in a variety of forms (e.g., words, graphs, charts, diagrams)

- Write, speak, and present content in a way that compels audiences to pay attention and understand new information

- Listen and ask questions to understand and appreciate the points of view of others

- Share information using a range of information and communications technologies (e.g., voice, email, computers)

- Use relevant scientific, technological, and mathematical knowledge and skills to explain or clarify ideas (e.g., a conference presentation or trifold or a non-disclosure agreement)

Likewise, the non-profit National Association of Colleges and Employers surveys hundreds of employers annually and has found that, in the last several years, they consistently rank the following four skills as most desirable ahead of fifth-ranked technical skills:

- Critical thinking and problem solving

- Professionalism and work ethic

- Teamwork

- Oral and written communication (NACE, 2016)

When employers include these interrelated soft skills in job postings, it’s not because they copied everyone else’s job posting but because they really want to hire people with those skills. From experience, they know that such skills directly contribute to the success of any operation, no matter whether you’re in the public or private sector, because they help attract and retain customers and client organizations.

Traditional hiring practices filter out applicants who have poor communication skills, starting with a “written exam”—the résumé and cover letter. As documents that represent you in your physical absence, these indicate whether you are detail-oriented; reviewers note how you organize information and whether you can compose proper, grammatically correct sentences and paragraphs. If you pass this evaluation, you are invited to the “oral exam,” where your face-to-face conversational skills are assessed. If you prove that you have strong soft skills in this two-stage filter, especially if you come off as friendly, happy, and easy to work with in the interview, an employer will be more likely to hire you, keep you, and trust you with coworkers and clients.

The latest thinking in human resources (HR), however, is that both of those traditional filters are unreliable; applicants can use outside resources to strengthen their documents without learning the critical skills discussed in this book. You could get someone else to write your résumé and cover letter for you, or you may follow a template and replace someone else’s details with your own. Though most job competitions for well-paying jobs will yield exceptionally good and bad résumés and cover letters amid a tall stack of applications, most tend to look the same because most applicants follow fairly consistent advice about how to put them together. Likewise, you can train for an interview and “fake it to make it” (Cuddy, 2012), then go back to being your less hireable self in the workplace, only to be the first one “let go” during departmental changes or re-organizations.

Recruiters at the most successful companies, such as tech giant Google, have looked at the big data on hiring and found that traditional criteria, including GPA and technical-skills test scores in the interview process, are poor predictors of how well a hire will perform and advance. New hires with only core technical skills, even if exceptionally advanced, do not necessarily become successful employees; in fact, they are the most replaceable in any organization, especially in STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) industries (Sena & Zimm, 2017). According to Business Insider, Google’s recruiters took an analytics approach like that portrayed in the 2011 film Moneyball and found that key predictors of success are instead personal traits, especially:

- Adaptability: the curiosity-driven agility to solve problems through independent, on-the-job learning

- Resilience: the “emotional courage” to persevere through challenges

- Diverse background: well-roundedness coming from exposure to multicultural influences and engagement in diverse extracurricular activities, including sports

- Friendliness: being a “people person,” happy around others, and eager to serve

- Conscientiousness: an inner drive to strive for detail-oriented excellence in completing tasks to a high standard without supervision (Patel, 2017)

- Professional presence: evidence of engaging in professional activities online

- Social and emotional intelligence: according to the CEO of Knack, a Silicon Valley start-up that uses big data and gamification in the hiring process to identify the traits of successful employees, “everything we do, and try to achieve inside organizations, requires interactions with others”; no matter what your profession or “social abilities, being able to intelligently manage the social landscape, intelligently respond to other people, read the social situation and reason with social savviness—this turns out to differentiate between people who do better and people who don’t do as well” (Nisen, 2013).

In other words, the quality of your communication skills in dealing with the various audiences that surround you in your workplace is the best predictor of professional success.

Key Takeaway

Employers value employees who excel in communication skills rather than just technical skills because, by ensuring better workplace and client relations, they contribute directly to the viability of the organization.

Exercises

- Go to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics site and find your chosen profession (i.e., the job your program will lead to) via the Occupation Finder page. List the particular document types you will be responsible for communicating with in a professional capacity by reading closely through the drop-downs.

- Prepare a SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats) Analysis of your current communication norms by interviewing 2–3 close friends, relatives, and academic peers about their perceptions of you.

References

Cuddy, A. (2012). Your body language may shape who you are. TED Talks. Retrieved from https://www.ted.com/talks/amy_cuddy_your_body_language_shapes_who_you_are

Graduate Management Admission Council. (2020). Employers Still Seek Communication Skills in New Hires. MBA.com. Retrieved from https://www.mba.com/information-and-news/research-and-data/employers-seek-communications-skills

Indeed Editorial Team. (2018). Top 10 Communication Skills for Career Success. Indeed. Retrieved from https://www.indeed.com/career-advice/resumes-cover-letters/communication-skills

National Association of Colleges and Employers. (2016, April 20). Employers identify four “must have” career readiness competencies for college graduates. Retrieved from https://www.naceweb.org/career-readiness/competencies/employers-identify-four-must-have-career-readiness-competencies-for-college-graduates/

Nisen, M. (2013, May 6). Moneyball at work: They've discovered what really makes a great employee. Business Insider. Retrieved from http://www.businessinsider.com/big-data-in-the-workplace-2013-5

Patel, V. (2017, August 7). Soft skills are the key to finding the most valuable employees. Forbes. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/theyec/2017/08/07/soft-skills-are-the-key-to-finding-the-most-valuable-employees/2/#5604d5c616e7

Sena, P., & Zimm, M. (2017, September 30). Dear tech world, STEMism is hurting us. VentureBeat. Retrieved from https://venturebeat.com/2017/09/30/dear-tech-world-stemism-is-hurting-us/

1.1.3: A Diverse Skill Set Featuring Communications Is Key to Survival

Section 1.1.3 Learning Objectives

- Consider how communication skills will ensure your future professional success.

The picture painted by this insight into what employers are looking for tells us plenty about what we must do about our skill set to have a fighting chance in the fierce competition for jobs: diversify it and keep our communication skills at a high level. Gone are the days when someone would do one or two jobs throughout their entire career. According to a U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1979—which tracks the lives of workers from the baby boomer generation (“individuals born from 1957 to 1964,” p. 1)—the retiring generation held an average of 12 jobs in their careers (BLS, 2021); with new technologies changing the future of office and time-dependent paid opportunities for employment (like Lyft and Uber for taxi and shuttle services), new opportunities may involve gigging for several employers at once rather than for one (Mahdawi, 2017).

Futurists tell us that the “gig economy” will evolve alongside advances in AI (artificial intelligence) and automation that will phase out jobs of a routine and mechanical nature with machines. On the bright side, jobs that require advanced communication skills will still be safe for humans because AI and robotics cannot so easily imitate them in a way that meets human needs. Taxi drivers, for instance, are a threatened species now with Uber encroaching on their territory and will certainly go extinct when the promised driverless car revolution arrives in the next 10-15 years, along with truckers, bus drivers, and dozens of other auto- and transport-industry roles (Frey, 2016). They can resist, but the market will ultimately force them into retraining and finding work that is hopefully more future-proof—work that prioritizes the human element.

Indeed, current predictions from an HSBC Global Research study note that positions such as administrative assistants and groundskeepers are at high risk of being affected by automation by the mid-2020s to 2030s (Fanusie, 2021). Some of those will be eliminated outright, but most will be redefined by requiring new skill sets that cannot be automated so easily. The 36% of jobs at low risk are those that require either advanced soft skills and emotional intelligence featured in roles such as managers, nurses, and teachers (Lamb, 2016), creativity, or advanced STEM skills in developing and servicing those technologies (Mahdawi, 2017; Riddell, 2017).

Read more:

The Future of Jobs Report 2025 from the World Economic Forum

Since the future of work is a series of careers and juggling several gigs simultaneously, communication skills are key to transitioning between them all. The gears of every career switch and new job added are greased by the soft skills that help convince your new employers and clients to hire you or, if you strike out on your own, convince your new partners and employees to work with or for you. Career changes certainly are not the signs of catastrophe that they perhaps used to be; usually, they mark moves up the pay scale so that you end your working life where you should: far beyond where you started in terms of both your role and pay bracket.

You simply cannot make those career and gig transitions without communication skills. In other words, you will be stuck on the first floor of entry-level gigging unless you have the soft skills to lift you up and shop you around. A nurse who graduates with a diploma and enters the workforce quilting together a patchwork of part-time gigs in hospitals, care homes, clinics, and schools, for instance, will not still be exhausted by this juggling act if they have the soft skills to rise to decision-making positions in any one of those places. Though the job will be technologically assisted in ways that it never had been before, with machines handling the menial dirty work, the fundamental human need for human interaction and decision-making will keep that nurse employed and upwardly mobile. The more advanced your communication skills develop as you find your way through the gig economy, the further up the pay scale you’ll climb.

Exercises

- Again, using the Bureau of Labor Statistics site, go to the Occupational Outlook Handbook page and search for your chosen profession (i.e., the job your program will lead to). Using the sources listed below as well as other internet research, explain whether near- and long-term projections predict that your job will survive the automation and AI revolution or disruption in the workforce. If the role you’re training for will be redefined rather than eliminated, describe what new skill sets will “future proof” it.

- Plot out a career path starting with your chosen profession and where it might take you. Consider that you can rise to supervisory or managerial positions within the profession you’re training for but then transfer into related industries. Name those related industries and consider how they too will survive the automation/AI disruption.

References

Fanusie, I. (2021, November 17). These are the jobs at the highest risk from automation: HSBC. Yahoo Finance. Retrieved from https://finance.yahoo.com/news/these-are-the-jobs-with-the-highest-risk-of-automation-190752107.html

Frey, T. (2016, April 5). 128 Things that will disappear in the driverless car era. Retrieved from http://www.futuristspeaker.com/job-opportunities/128-things-that-will-disappear-in-the-driverless-car-era/

Mahdawi, A. (2017, June 26). What jobs will still be around in 20 years? Read this to prepare your future. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2017/jun/26/jobs-future-automation-robots-skills-creative-health

Riddell, C. (2017, February 10). 10 high-paying jobs that will survive the robot invasion. Retrieved from https://careers.workopolis.com/advice/10-high-paying-jobs-will-survive-robot-invasion/

World Economic Forum. (2020, October 20). The Future of Jobs Report 2020. World Economic Forum. Retrieved from https://www.weforum.org/reports/the-future-of-jobs-report-2020

1.1.4: Communication Represents You and Your Employer

Section 1.1.4 Learning Objectives

- Recognize that the quality of your communication represents the quality of your company.

Imagine a situation where you are looking for a contractor for a custom job you need to be done on your car and you email several companies for a quote breaking down how much the job will cost. You narrow it down to two companies who have about the same price, and one gets back to you within 24 hours with a clear price breakdown in a PDF attached in an email that is friendly in tone and perfectly written. The other took four days to respond with an email that looked like it was written by a sixth grader with multiple grammar errors in each sentence and an attached quote that was just a scan of some nearly illegible chicken-scratch writing. Comparing the communication styles of the two companies, choosing who you’re going to go with for your custom job is a no-brainer.

Of course, the connection between the quality of their communication and the quality of the job they’ll do for you is not water-tight, but it’s a fairly good conclusion to jump to, one that customers will always make. The company representative who took the time to ensure their writing was clear and professional, even proofreading it to confirm that it was error-free, will probably take the time to ensure the job they do for you will be the same high-caliber work that you’re paying for. By the same token, we can assume that the one who did not bother to proofread their email at all will likewise do a quick, sloppy, and disappointing job that will require you to hound them to come back and do it right—a hassle you have no time for. We are all picky, judgmental consumers for obvious reasons: we are careful with our money and expect only the best work value for our dollar.

Good managers know that about their customers, so they hire and retain employees with the same scruples, which means they appreciate more than anyone that your writing represents you and your company. As tech CEO Kyle Wiens (2012) says, “Good grammar is credibility, especially on the internet,” where your writing is “a projection of you in your physical absence.” Just as people judge flaws in your personal appearance, such as a stain on your shirt or broccoli between your teeth, suggesting a sloppy lack of self-awareness and personal care, so they will judge you as a person if it’s obvious from your writing that “you can’t tell the difference between their, there, and they’re.”

As the marketing slogan goes, you do not get a second chance to make a first impression. If potential employers or clients (who are, essentially, your employers) see that you care enough about details to write a flawless email, they will jump to the conclusion that you will be as conscientious in your job and are thus a safe bet for hire. Again, it’s no guarantee of future success, but it increases your chances immeasurably. As Wiens says of the job of coding in the business of software programming, “Details are everything. I hire people who care about those details," but you could substitute “programmer” with any job title and it would be just as true.

Key Takeaway

The quality of your communication represents the quality of your work and the organization you work for, especially online, when others have only your words to judge.

Exercise

Describe an incident when you were disappointed with the professionalism of a business you dealt with, either because of shoddy work, poor customer service, shabby online or in-person appearance, etc. Explain how the quality of their communication impacted that experience and what you would have done differently if you were in their position.

References

Wiens, K. (2012, July 20). I won't hire people who use poor grammar. Here's why. Harvard Business Review. Retrieved from https://hbr.org/2012/07/i-wont-hire-people-who-use-poo/

Test your Understanding

1.2: Communicating in the Digital Age

Section 1.2 Learning Objectives

- Distinguish between personal and professional uses of communications technology in ways that ensure career success and personal health.

- Select and use common, basic information technology tools to support communication.

How many texts or instant messages do you send in a day? How many emails? Do you prefer communicating by text, instant message app (e.g., Snapchat), or generally online instead of face-to-face in person with businesses? If you’re an average millennial sending out and receiving more than the 2013 average of 128 texts per day (Burke, 2016), that’s a lot of reading and responding quickly in writing—so much more than people your age were doing 20 years ago. Even if just for social reasons, you are probably writing more than most people in your demographic have at any point in human history. This is mostly an advantage because it gives you a baseline comfort with the writing process, even if the quality of that writing probably is not quite where it should be if you were doing it for professional reasons.

Where being overly comfortable with texting becomes a disadvantage, however, is when it is used as a way of avoiding the in-person, face-to-face communication that is vital to the routine functioning of any organization. As uncomfortable as it may sometimes be, especially for teens in their “cringey awkward years,” developing conversational skills throughout that decade is hugely important by the time they enter a workforce mostly populated by older generations who grew up without smartphones, developed those advanced conversational skills the hard way by making mistakes and learning from them, and expect well-developed conversational skills of younger generations entering the workforce. Though plenty of business is done online these days, there really is no good substitute for face-to-face interaction.

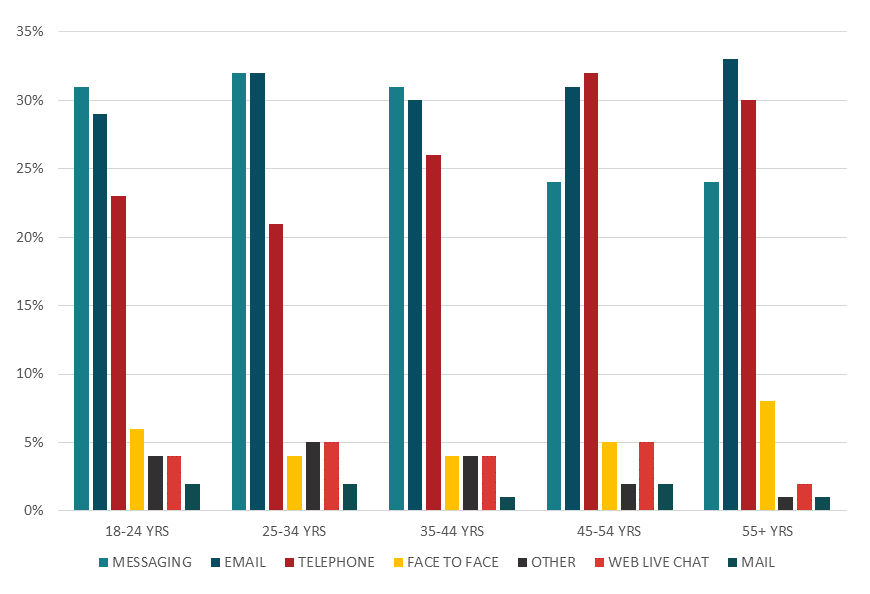

According to Twilio’s 2016 consumer report on messaging, however, the most preferred channel for customer service among 18- to 24-year-olds (said 31% of respondents) is by text or instant messaging, followed closely by email (p. 8). Face-to-face interaction, however, is preferred by only 6% of respondents.

| Messaging | Telephone | Face-to-Face | Other | Web Live Chat | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18-24 years | 31% | 29% | 23% | 6% | 4% | 4% | 2% |

| 25-34 years | 32% | 32% | 21% | 4% | 5% | 5% | 2% |

| 35-44 years | 31% | 30% | 26% | 4% | 4% | 4% | 1% |

| 45-54 years | 24% | 31% | 32% | 5% | 2% | 5% | 2% |

| 55+ years | 24% | 33% | 30% | 8% | 1% | 2% | 1% |

Figure 1.2: Preferred customer service channel by age group (Twilio, 2016)

Customer service aside, face-to-face interactions are still vitally important to the functioning of any organization. In a study on the effectiveness of in-person requests for donations versus requests by email, for instance, the in-person approach was found to be 34 times more successful (Bohns, 2017). We instinctively value human over machine interaction in many (but not all) situations we find ourselves. Though some jobs like nurse or therapist simply cannot function without in-person interaction and would be the last to be automated (if ever), most others will involve a mix of written and face-to-face communication. During the COVID-19 pandemic, for instance, eHealth, telehealth, and/or telemedicine solutions assisted with face-to-face communication in delivering health care services to patients living with chronic diseases/conditions. While physical distancing emerged as the most effective way to reduce spread of COVID-19, Bitar and Alismail (2021) noted the value “of using such technological solutions in the future when the COVID-19 crisis is over” in circumstances where physical and transportation limitations may continue (p. 16).

Our responsibility in handling that mix requires that we become competent in the use of a variety of devices that bring us a competitive advantage in our work (see Table 1 below). By working in the cloud with our smartphones and laptop, desktop, or tablet devices, for instance, we can collaborate with individuals or teams anywhere and anytime, as well as secure our work in ways we could not when files were tied to specific devices. Through the years, new technology trends will offer up new advantages with new devices that we will have to master to stay competitive.

Those advantages are double-edged swords, however, so it is important that we manage the risks associated with them. With so much mobile technology enabling us to communicate and work on the go, from home, or anywhere in the world with a Wi-Fi connection, we are expected to be always available to work, to always be “on”—even after hours, on weekends, and on vacation—lest we lose a client to someone else who is available at those times. The early bird gets the worm. Add to that the psychological and physiological impacts of adults averaging 8.8 hours of screen time per day (Dunckley, 2014; Twenge, 2017; Nielsen, 2016, p. 4). With this number increasing, it’s no wonder that problematic technology use, including screen addiction, is a growing concern among both health and technology experts (Phillips, 2015; Fawcett, 2019). Beyond being an effective communicator and professional in general, just being an effective person—in the sense of being physically and mentally healthy—requires knowing when not to use technology.

But in the workplace, especially if it’s a traditional office environment, we must be savvy in knowing which technology to use rather than always reach for our smartphones. The modern office offers up a variety of tools that increase productivity and raise the bar on the quality and appearance of the work we do. You must be competent in the use of the latest in presentation technology, voice and video conferencing, company intranets, multifunctional printers, and so on. Even using the latest industry-wide software and social media apps ensures that your communication looks and functions on-point rather than in an antiquated way that makes you look like you stopped trying six years ago.

All such technology will change rapidly in our lifetimes, some will disappear completely, and new devices and software will emerge and either dominate or also disappear. So long as others are using the dominant technology for an advantage in your type of business, then it’s on you to use them also to avoid falling behind and getting stuck on obsolete technology that fewer and fewer people use. Depending on how successful you’re driven to be, you would be wise to even get ahead of the curve by adopting emerging technology early.

Key Takeaway

Use an array of dominant communications technology to maintain a competitive advantage, and know when to put it all away in favor of in-person communication.

Exercises

- Keep a daily journal recording the length of time you spend using various screen devices, such as your smartphone, tablet, laptop, desktop, TV, etc. Also record the amount of time you use these for school-related activities, social networking activities, and entertainment (which you can further break down into passive viewing, such as watching Netflix and YouTube videos, and interactive use such as gaming). What conclusions can you draw from quantifying your screen time? Are your habits consistent each day or throughout the week? Explain what benefit you derive from these activities and how they might help and hinder your professional development.

- Record how many texts or instant messages you send and receive per day over the course of a week. Count how many you sent because you had good reason to do so by text (as opposed to phone call), such as to reply in the same channel you received a message or to send a message quietly so as to avoid disturbing others around you (e.g., in class or late at night). Identify how many messages you could have exchanged merely by calling the person up and having a quick back-and-forth or waiting to talk to them in person. What conclusions can you draw from quantifying your messaging habits?

- Research what future technology might revolutionize the work you’re training to do. Bearing in mind the job description on the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ study on the Impact of New Technologies on the Labor Market, what tasks identified there can be automated? What will still be done by you because it involves the human element that cannot be automated?

References

Bitar, H., & Alismail, S. (2021). The role of eHealth, telehealth, and telemedicine for chronic disease patients during COVID-19 pandemic: A rapid systematic review. Digital health, 7, 20552076211009396.

Bohns, V. K. (2017, April 11). A face-to-face request is 34 times more successful than an email. Harvard Business Review. Retrieved from https://hbr.org/2017/04/a-face-to-face-request-is-34-times-more-successful-than-an-email

Dell, K., Nestoriak, N., & Marlar, J. (2020). Assessing the Impact of New Technologies on the Labor Market: Key Constructs, Gaps, and Data Collection Strategies for the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/bls/congressional-reports/assessing-the-impact-of-new-technologies-on-the-labor-market.htm

Dunckley, V. L. (2014, February 27). Gray matters: Too much screen time damages the brain. Psychology Today. Retrieved from https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/mental-wealth/201402/gray-matters-too-much-screen-time-damages-the-brain

Fawcett, C. (2019). Beyond the Digital Border: Modern Life on the Network. Jeunesse: Young People, Texts, Cultures 11(2), 321-339. Retrieved from https://muse-jhu-edu.ezproxy.lib.ou.edu/article/750600

Nielsen. (2016). The Nielsen Total Audience Report. Retrieved from http://www.nielsen.com/content/dam/corporate/us/en/reports-downloads/2016-reports/total-audience-report-q1-2016.pdf

Phillips, B. (2015). Problematic technology use: The impact of capital enhancing activity. Association for Information Systems Electronic Library. Retrieved from http://aisel.aisnet.org/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1003&context=sais2015

Twenge, J. M. (2017, September). Have smartphones destroyed a generation? The Atlantic. Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2017/09/has-the-smartphone-destroyed-a-generation/534198/

Twilio. (2016). Understand how consumers use messaging: Global mobile messaging consumer report 2016. Retrieved from https://assets.contentful.com/2fcg2lkzxw1t/5l4ljDXMvSKkqiU64akoOW/cab0836a76d892bb4a654a4dbd16d4e6/Twilio_-_Messaging_Consumer_Survey_Report_FINAL.pdf

U. S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2021, August). Number of Jobs, Labor Market Experience, Marital Status, and Health: Results from a National Longitudinal Survey. U. S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/nlsoy.pdf

Test Your Understanding

1.3: The Communication Process

Section 1.3 Learning Objectives

- Illustrate the communication process to explain the end goal of communication.

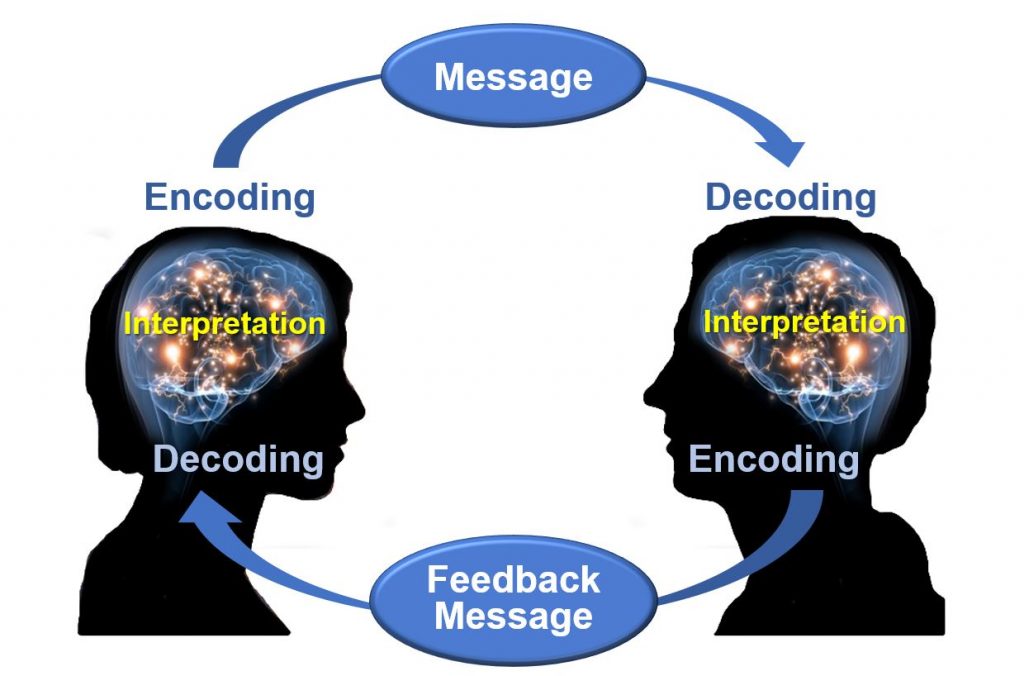

Stripping away the myriad array of technology and channels we use to communicate, at its core the whole point of communication is to move an idea from your head into someone else’s so that they understand that idea the same way you do. If there is work to be done to ensure that the person receiving a message understands the sender’s intended meaning, the responsibility falls mainly on the sender. But the receiver is also responsible for confirming their understanding of that message, making communication a dynamic, cyclical process.

Breaking down the communication cycle into its component parts is helpful to understand your responsibilities as both a sender and receiver of communication, as well as to troubleshoot communication problems. First, let’s appreciate how amazing it is that you can form an idea as an incredibly complicated pattern of electrical impulses in your brain and plant that same pattern of impulses in someone else’s brain very easily. It may sound complicated, but you are wired to do this every second of the day.

Sources: Kisspng, 2018; Web Editor 4, 2017

According to the Osgood-Schramm model of communication (1954), you first encode an idea into a message when you want to communicate that idea with the outside world (or even just to yourself). If you choose to send that message in the channel of in-person speech (as opposed to other spoken, written, or visual channels, examples of which are listed in Table 1), you first form the word into the language in which you will be understood, then send electrical impulses to your lungs to push air past your vocal chords, send electrical impulses to vibrate your vocal chords to bend the air into a sound, shape those sound waves further with your jaw, tongue, and lips, send that sound on its way through the air till it reaches the eardrum of the receiver, which vibrates in a manner that tickles the cochlear cilia in their inner ear, which sends a patterned electrical impulse into their brain, which proceeds to decode that impulse into the same pattern of electrical impulses that constitute the same idea that you had in your brain.

| Verbal | Written | Visual |

|---|---|---|

| In-person speech | Drawings, paintings | |

| Phone conversation | Text, instant message | Photos, graphic designs |

| Voice over internet protocol (VoIP) | Report, article, essay | Body language (e.g., eye contact, hand gestures) |

| Radio | Letter | Graphs |

| Podcast | Memo | Font types |

| Voicemail message | Blog | Semaphore |

| Intercom | Tweet | Architecture |

Table 1.3: Examples of Communication Channels

To ensure that the message was decoded properly and understood, the receiver then encodes and sends an intentional or unintentional feedback message that the first sender receives and decodes; when the first sender understands that the receiver understood the first message, then the goal of the communication process has been achieved. If you stated, for instance, “I’m hungry” and the receiver of that message responded by saying, “Me too. Let’s get a taco,” you can be sure that they understood your intended meaning without them stating that they understood. From there, the message and feedback can continue to cycle around in a back-and-forth conversation that exchanges new ideas and offers opportunities for the receiver of those messages to ask for clarification if understanding is not achieved as intended.

But the receiver’s intentional or unintentional feedback message need not be in the same channel as the sender’s. If the receiver of the above “I’m hungry” message nodded and held up a cookie for you to take instead of saying anything at all, it would be clear from their intentional nonverbal expressions and actions that they correctly decoded and understood your meaning: that you’re not only hungry but also your hunger would be somewhat relieved by the cookie at hand. And if the receiver responded in no other way but with a rumble of their stomach, their unintentional feedback also confirmed understanding of the message.

As you can see, this whole process is easier done than said because you encode incredible masses of data to transmit to others all day long in multiple channels, often at once, and are likewise bombarded with a constant multi-channel stream of information in each of your five senses that you decode without being even consciously aware of this complex process. You just do it. Even when you merely talk to someone in person, you’re communicating not just the words you’re voicing but also through your tone of voice, volume, speed, facial expressions, eye contact, posture, hand movements, style of dress, etc. All such channels convey information besides the words themselves, which, if they were extracted into a transcript of words on a page or screen, communicate relatively little. In professional situations, especially in important ones such as job interviews or meetings with clients where your success depends entirely on how well you communicate across the verbal and all the nonverbal channels, it’s extremely important that you be in complete control of all of them and present yourself as a detail-oriented pro—one they can trust to get the job done perfectly for their money.

Key Takeaway

As a cyclical exchange of messages, the goal of communication is to ensure that you’ve moved an idea in your head into someone else’s head so that they understand your idea as you understood it.

Exercises

- Without looking at the communication process model above, illustrate your own theory of how communication works and label the diagram’s parts. Compare it to the model above and discuss the advantages and disadvantages of each.

- Table 1.3 above compiles only a partial list of channels for verbal, written, and visual channels. Extend that list as far as you can push it.

References

Kisspng. (2018, March 17). Clip art - Two people talking. Retrieved from https://www.kisspng.com/png-clip-art-two-people-talking-569998/

Schramm, W. L. (1954). The Process and Effects of Mass Communication. Champaign, IL: U of Illinois P.

Web Editor 4. (2017, January 12). A pattern of brain activity may link stress to heart attacks. Daily Messenger. Retrieved from https://dailymessenger.com.pk/2017/01/12/a-pattern-of-brain-activity-may-link-stress-to-heart-attacks/

Test Your Understanding

1.4: Troubleshooting Miscommunication

Section 1.4 Learning Objectives

- Troubleshoot communication errors by breaking down the communication process into its component parts.

Now with a basic overview of the communication process under our belts, troubleshooting miscommunication becomes a matter of locating where in the cyclical exchange of messages lies the problem: with the sender and the message they put together, the receiver and their feedback message, or the channel in the context of the environment between them. Identifying the culprit can help avoid one of the most costly errors in any business. According to Susan Washburn, communication problems can lead to:

- Conflict, damaged relationships, and animosity within an office and lost business with clients

- Productivity lost and resources wasted fixing problems that could have been avoided with proper communication

- Inefficiency in taking much longer to do tasks easily completed with better communication, leading to delays and missed deadlines

- Missed opportunities

- Unmet objectives due to unclear or shifting requirements or expectations

Let’s examine some of these in the real and imagined scenarios below.

If the receiver of the above “I’m hungry” message responded with something like “Yes, and I’m Romania,” to the sender the receiver would appear for a moment to have misunderstood the message as it was intended, though indeed the receiver did but chose to respond in a way that plays with the unintended possible misinterpretation of “hungry” as the homophone (a word that sounds the same as another completely different word) “Hungary,” a European country next to Romania. Part of the beauty and fun of language is that words—especially spoken ones—can have multiple meanings, which means that senders must be careful to anticipate potential misinterpretations of their messages due to carelessness toward ambiguities. In any case, once the joke is understood, the first sender can rest assured that the feedback message still confirms that the first message was understood, which is the end goal of communication.

Most jokes toy with communication breakdowns in harmless ways, but when breakdowns happen unintentionally in professional situations where opportunities, money, and reputations are on the line, their serious costs make them no laughing matter. Take, for instance, the misplaced comma that cost Rogers Communications $1 million in a contract dispute over New Brunswick telephone poles (Austen, 2006) or the absence of an Oxford comma that cost Oakhurst Dairy $10 million in a Maine labor dispute (Associated Press, 2017). In both cases, everyone involved would have preferred to continue with business as usual rather than sink time and resources into protracted legal and labor disputes all stemming from a mere misplaced or missing comma. To avoid costly miscommunication in any business or organization, senders and receivers must be diligent in fulfilling their communication responsibilities and be wary of potential misunderstandings throughout the communication cycle outlined above.

1.4.1: Sender-related Miscommunication

The responsibility of the sender of a message is to make it as easy as possible to understand the intended meaning. If work must be done to get your point across, it is on you as the sender to do all you can to make that happen. (The receiver also has their responsibilities that we’ll examine below, but listening and reading are not necessarily as labor-intensive as composing a message in either speech or writing.) This is why grammar, punctuation, and even document design in written materials—as well as excellent conversational and presentation skills—are so important: sender errors in these aspects of communication lead to readers’ and audiences’ confusion and frustration, which get in the way of their understanding the meaning you intended. If senders of messages fail to anticipate their audience’s needs and miss the target of writing or saying the right thing in the right way to get their messages across, they bear the responsibility for miscommunication and need to pay close attention to the lessons throughout this textbook to help them get back on target.

If the sender has any doubt that their message is being understood, it’s also on them to check in to make sure. If you are giving a presentation, for instance, you can employ several techniques to help ensure that your audience stays with you:

- Ensure that they can properly hear you by projecting your voice so that even the people in the back row can hear you properly; check that they can by asking if they can hear you just fine. Use a microphone if one is available, even if no one acknowledges an inability to hear; those who are hard of hearing may not want to identify themselves as such. In addition, using a microphone will assist in video and audio recording.

- Get them involved and engaged by asking for a show of hands on topical questions.

- Ask them to ask questions if they do not understand anything; make them feel at ease to ask questions by saying that there are no stupid questions and that if a question occurs to any one of them, it is probably also occurring to the rest.

- Flag important points and, several minutes later, ask them to summarize them back to you when you are relating them to another major point.

1.4.2: Channel-related Miscommunication

Errors can also be blamed on the medium of the message, such as the technology and the environment—some of which can slide back to choices the sender makes, but others are out of anyone’s control. If you need to work out the terms of a sale with a supplier a few towns over before you draw up the invoice (and time is of the essence), sending an email and expecting a quick response would be foolish when you (a) have no idea if anyone’s there to write back right away and (b) would potentially need to go back and forth over the terms; this exchange could potentially take days, but you only have an hour. The smart move is instead to call the supplier so that you can have a quick back-and-forth. If you need to, you could also text them to say that you’re calling to hammer out the details before writing it up. However, you would not call using a cellphone from inside a parking garage, because the reception (or interference) could hinder the quality or possibility of receiving the call. If phone lines and the internet are down due to equipment malfunction (despite paying your bills and buying trustworthy equipment), however rare that might be, the problem is obviously out of your hands and in the environment. Otherwise, it’s entirely up to you to use the right channels the correct way in the environments best suited to clear communication to get the job done.

1.4.3: Receiver-related Miscommunication

The responsibility of the receiver of a message is to be able not only to actively read or hear the message itself but also to understand the nuances of that message in context. Say you were a relatively recent hire at a company and were in line for a promotion for the excellent work you’ve been doing lately, it’s 11:45 a.m., you just crossed paths with your manager in the hallway, and she’s the one who said “I’m hungry” (to use our example from above). That statement is the primary message, which simply describes how the speaker feels. But if she says it in a manner that—with nonverbals (or secondary messages) such as eyebrows raised, signaling interest in your response, and a flick of the head toward the exit—suggests an invitation to join her for lunch, you would be foolish not to put all of these contextual cues together and see this as a professional opportunity worth pursuing. If you responded with “Enjoy your lunch!” your manager would probably question your social intelligence and whether you would be able to capitalize on opportunities with clients when cues lined up for business opportunities that would benefit your company. But if you replied, “I’m starving, too. May I join you for lunch? I know a great place around the corner,” you would be correctly interpreting auxiliary messages such as your manager’s intention to assess your professionalism outside of the traditional office environment.

Say you arrive at the lunch spot with your manager and sit down to eat, but it’s too noisy to hear each other well; you would be equally foolish to use this environmental problem as an excuse not to talk and instead just browse your social media accounts on your phone (perhaps your usual lunchtime routine when eating solo) in front of her. You could accommodate her need to hear you by raising your voice, but the image of you shouting at your manager also sends all the wrong messages. Rather, if you cite the competing noise as a reason to move to a quieter spot where you can converse with her in a way that displays the polish of your manners and ultimately positions you nicely for the promotion, she would understand that you have the social intelligence to control the environmental conditions in ways that prioritize effective communication.

Of course, so much more can go wrong with the receiver. In general, the receiver may lack the knowledge to understand your message; if this is because you failed to accommodate their situation—say you used formal language and big, fancy words but they do not understand because they are ESL (English as a Second Language)—then the blame shifts back to you because you can do something about it. You could instead use more plain, easy-to-understand language. If your audience is a coworker who should know what you’re talking about when you use the jargon of your profession, but they do not because they’re in the wrong position and in over their head, the problem is with the receiver (and perhaps the hiring process).

Another receiver problem may have to do with attitude. If a student, for instance, believes that they do not need to take a class in Communications because they speak the language, think their high school English classes were a complete joke, and figure they will traverse workplace communication on their own, then the problem with this receiver is that overconfidence prevents them from keeping the open mind necessary to learn and take direction. Carried into the workplace, such arrogance would prevent them from actively listening to customers and managers, and they would most likely fail until they develop necessary active listening skills (see below). Employers like employees who can solve problems on their own; those who are unable to take direction can cause costly problems between staff members and clients, resulting in strained relationships, poor morale, and lost business.

The picture emerging here, then, is one where many factors must work in concert to achieve communication of intended meaning. The responsibility of reaching the goal of understanding in the communication process requires the full cooperation of both the sender and receiver of a message to make the right choices and avoid all the perils—personal and situational—that lead to costly miscommunication.

Key Takeaway

Being an effective professional involves knowing how to avoid miscommunication by upholding one’s responsibilities in the communication process toward the goal of ensuring proper understanding.

Exercise

Describe a major miscommunication that you were involved in lately and its consequences. Was the problem with the sender, channel, environment, receiver, or a combination of these? Explain what you did about it and what you would do (or advise someone else to do) to avoid the problem in the future.

References

Associated Press. (2017, March 21). Lack of comma, sense, ignites debate after $10m US court ruling. CBC News | Business. Retrieved from http://www.cbc.ca/news/business/comma-lawsuit-dairy-truckers-1.4034234

Washburn, S. (2008, February). The miscommunication gap. ESI Horizons, 9(2). Retrieved from http://www.esi-intl.com/public/Library/html/200802HorizonsArticle1.asp?UnityID=8522516.1290

Test Your Understanding

1.5: Listening Effectively

Section 1.5 Learning Objectives

- Reframe information gained from spoken messages in ways that show accurate analysis and comprehension.

If most communication is text-based, why is it still important to be an effective listener? Why not just wait till everyone who’s grown up avoiding in-person contact in favor of filtering all social interaction through their smartphones dominate the workforce so that conversation can be done away with at last?

Perhaps the first rule in business is to know your customer. If you do not know what they want or need, you cannot successfully supply that demand, and no one’s going to buy what you have to sell. If you do not actively listen to what your customers or managers say they want or fail to piece together what they do not know they want from their description of a problem they need you to solve, then you may just find yourself always passed over for advancement. Business “intel” gleaned from knowledge- and needs-driven conversation is the lifeblood of any business, as is the daily functioning of anyone working within one.

A receiver’s responsibilities in the communication process will be to use their senses of hearing, vision, and even touch, taste, and smell to understand messages in whatever channels target those senses. In the case of routine in-person communication, active listening and reading nonverbal social cues are vitally important to understanding messages, including subtext—that is, significant messages that are not explicitly stated but must be inferred from context and nonverbals. In the above case of the manager saying she’s hungry, for instance, she did not say, “Join me for lunch so I can base my decision about whether to promote you on your social graces, emotional intelligence, and conversational ability.” Rather, plenty of reading between the lines was required of the receiver to figure out that:

- This is an invitation to lunch that ought to be accepted

- Given the context, the invitation suggests that the manager is considering the receiver for the promotion (otherwise she would avoid the receiver altogether)

- This opportunity should be treated like an informal job interview

With so much of the communication process’s success riding on the responsibility of the receiver to understand both explicit and implicit messages, effective, active listening skills are keys to success in any business.

1.5.1: Receiver Errors

Unfortunately, plenty can go wrong on the receiver’s end in listening effectively and making the right inferences. We’ve already looked at the possibility that they may just lack knowledge about both the job and the broader context to understand fully the content of workplace messages and their underlying meanings. They may be:

- A poor reader of nonverbal social cues due to a lack of experience in developing conversational skills

- Distracted by their devices

- Experiencing too much internal “semantic noise” interference from their minds wandering off topic with distracting thoughts about non-work-related things even during work communication

- Too preoccupied rehearsing what they’re going to say on a topic because they would rather speak than listen, or they listen only to reply rather than to understand

- Trying to multitask by reading or browsing while listening, but doing neither very effectively (Sanbonmatsu et al., 2013)

Woman playing on her phone at work by rawpixel.com is CC0 (public domain)

Many students struggle with this. Some have difficulty being patient enough to listen and would rather speak, otherwise known as grandstanding. In all such cases, the problem is passive listening—when you merely hear noises and barely register the meaning of the message because you have a preoccupying internal agenda that is more compelling. Once again, however, communication requires that you do your fair share to ensure that the sender’s meaning is understood.

1.5.2: Be an Active Listener

Fortunately, everyone can practice being a more effective listener by making themselves aware of their own listening habits and actively seeking to improve them. Doing so certainly takes work, especially if your listening habits have been largely passive for most of your life and your attention span is short from a steady diet of small units of media content such as memes. If your problem is that your mind wanders, you must train yourself to focus on the message at hand rather than consume other media in a failed effort to multitask or get distracted by the internal monologue that tries to whisk you away from the present. Work on just being present. Take the earbuds out and keep your cellphone in your pocket when someone is talking, including your college instructors. (When your instructors see you staring intently in the direction of your crotch under your desk and your hands are twitching a little down there, they’re not stupid; they know you’re fiddling with your phone.) Would you tolerate someone blatantly ignoring you to focus on their phone if you were speaking right in front of them? It’s just plain rude, and doing this yourself could, in professional situations, get you blacklisted by managers, coworkers, and customers, resulting in missed opportunities.

Rather, maintain strong eye contact with the speaker to show active interest. Resist the social anxiety–driven urge to avert your eyes as soon as pupil-to-pupil contact lasting more than a second or two makes the human connection too real for comfort. Challenge that. Eye contact builds trust, so do not signal to the speaker that you have something to hide (such as a lack of confidence in yourself) by darting your eyes away. But do not fake attention either by maintaining eye contact while your mind is a million miles away; good communicators can tell from your nonverbals (like nodding in agreement at the wrong things) when the lights are on but no one’s home.

Perhaps the best strategy for active listening is to devote your brain’s full processing power to the message at hand. One way you can do this is to paraphrase the message (i.e., re-state it in your own words), then ask the speaker if you understood it correctly. Translating the message into words that resonate more with you than what the speaker used helps you remember it because you’ve personally invested yourself in it. You can find a way to make it your own without necessarily agreeing with it (but that helps too). By doing this, you signal to the speaker that you’ve completed the whole goal of communication: to understand the sender’s meaning as they intended it.

Another processing strategy is to think of questions you can ask for clarification. No matter how thoroughly a speaker covers a topic, you can probably find gaps to ask about for clarification. “I understand that you’re saying A, B, and C, but what happens to those in situations X, Y, and Z?” Identifying gaps requires keen interest and strong processing power of your brain. But it’s the kind of processing that sends the auxiliary message that you are interested in what the speaker says, which may lead to a deeper conversation and connection—the holy grail of networking.

Figuring out when to talk and when to listen also requires social skills. If you like to grandstand and you get impatient when someone else is talking, you must practice exercising some impulse control. Take turns! By hearing them out and reserving judgment, you can really learn something. If you’re dealing with someone like that—one who monologues and does not know when to pass the ball—you must be a good reader of nonverbal cues to capitalize on the right moment to jump in with the right thing to say. On the other end of the spectrum, it takes skill to know how to draw people who communicate mostly in silence out of their shells if it means that you will mutually benefit from it on a business or personal level.

If you spent too much of your youth lost in screen time rather than interacting in person with friends, however, there’s no time like now and the rest of your life to begin favoring human contact over technology. Of course, the technology will always be there and you will be great at using it when the situation calls for it. However, your professional and personal well-being depends on knowing how and when to do without it and to get back to what really matters: being human. From there, professional success follows from keeping the communication channels open to solve problems collaboratively one conversation at a time.

Key Takeaway

The receiver of a message plays a significant role in ensuring that the goal of understanding is achieved, which means active listening in the case of spoken messages.

Exercises

- Pair up with a classmate and do a role-play exercise where one of you tries to explain how to do something while the other multitasks and interrupts the other. Quiz the multitasker to see if they remember specific steps in the procedure described. Then try it again while the listener practices active listening. How do the two communication experiences compare? Discuss your findings.

- In a half-hour period of conversation with friends, see if you can count how many times you are interrupted, but do not tell them ahead of time that you’re counting for this. Share and compare with your classmates.

- Take Psychology Today’s 33-question (15 min.) Listening Skills Test. Grab a screenshot of your results and, below it and the heading “Barriers to Effective Listening,” write five barriers that particularly annoy you or prevent you from being an active listener—that you notice both in other people and in yourself. Below that and the heading “Effective Listening Strategies,” list five strategies, one for each of the barriers listed above, each identifying a strategy for overcoming the barrier.

References

Hall, A. (2012, July 14). To succeed as an entrepreneur, know your customer. Forbes. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/alanhall/2012/06/14/to-succeed-as-an-entrepreneur-know-your-customer/

Listening Skills Test. (n.d.). Psychology Today. Retrieved on December 17, 2020, from https://www.psychologytoday.com/tests/relationships/listening-skills-test

Sanbonmatsu, D. M., Strayer, D.L., Medeiros-Ward, N., Watson, J.M. (2013). Who multi-tasks and why? Multi-tasking ability, perceived multi-tasking ability, impulsivity, and sensation seeking. PLoS ONE 8(1): e54402. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0054402

Test Your Understanding