Chapter 5: The Writing Process—Editing

Sydney Epps

Chapter Learning Objectives

- Revise and edit documents and messages that are organized, complete, and tailored to specific audiences.

Whatever you do, don’t quit now! Self-correction is an essential part of the writing process, one that students or professionals skip at their peril. Say you flew through drafting a quick email. Glancing back to ensure that it’s correct in terms of its grammar, punctuation, spelling, and mechanics helps you avoid confusing your reader or embarrassing yourself. Communication errors within emails are like stains on your shirt or rips in your uniform: they give the impression that you are incompetent or apathetic about your messaging; professors and employers believe this shows a lack of attention to detail. In fact, they may even believe that poor messaging is a malware or phishing attack (Parsons et al., 2016).

Always keep in mind that people generalize to equate the quality of your writing with the quality of your work. Because readers tend to be judgmental, they may even draw bigger conclusions about your level of education, work ethic, and overall professionalism from even a small writing sample. When assessing résumés and cover letters—where your words are the first impression employers have of you—employers are judgmental about your writing because their customers will do so. Employers do not want their employees to represent their company in a way that makes it look like their organization produces shoddy and amateur work.

The final stage of the writing process involves managing your readers’ impressions by editing your draft from beginning to end. Initially, this involves returning to your goals at the start of the writing process and assessing where your document is in relation to the strategy set to achieve it. When you get a sense of how far your document is from achieving that primary purpose, you realize what needs to be done to close that gap—what you need to add, rewrite, delete, and improve. Your next move is a two-step editing process of substantial revisions and proof-editing. The order of these is crucial to avoid wasting time. You wouldn’t proofread for minor grammatical errors before substantial revisions because you may end up deleting paragraphs you meticulously proofread with a fine-tooth comb. Divide the editing process in the following order:

Figure 5: The four-stage writing process and stage 4 breakdown

- 5.1: Substantial Revisions

- 5.2: Proofreading for Grammar

- 5.3: Proofreading for Punctuation

- 5.4: Proofreading for Spelling

- 5.5: Proofreading for Mechanics

Reference

Parsons, K., Butavicius, M., Pattinson, M., Calic, D., Mccormac, A., & Jerram, C. (2016). Do users focus on the correct cues to differentiate between phishing and genuine emails?. arXiv preprint arXiv:1605.04717.

5.1: Substantial Revisions

Section 5.1 Learning Objectives

- Revise and edit documents and messages that are organized, complete, and tailored to specific audiences.

Before you begin your editing process with a bird’s-eye view of the whole document, it might be a good idea to step away from it altogether. Distancing yourself from the work you just drafted helps you approach it again with fresh eyes. This requires effective time management so that you have a solid draft ready well ahead of a deadline. Leaving enough time to shift attention to other work projects or your personal life, however, helps you forget a little what you were doing with the document in question. Ask yourself, Will that target reader understand what you’ve written in the order you’ve presented it? To complete their understanding of your topic, what do they need to see that isn’t in your draft yet? What parts are redundant, confuse the reader, or otherwise get in the way of their understanding and can just be deleted?

Alienating yourself from your own work helps give you the critical distance necessary to be more ruthless toward it than you are at the drafting stage. You cling too personally to the words you come up with at the drafting stage, whereas you would be more critical of the same words if they were written by someone else. Creating that critical distance helps you:

- Re-arrange the order that you originally plotted out at the outlining step, if need be

- Recognize gaps that must be filled with yet more draft material

- Chop out parts that don’t contribute to the purpose you set out to achieve, difficult as it may be to delete words that you labored into being

Before returning to the topic of trimming, however, let’s consider what you’re looking for when you evaluate your draft.

- 5.1.1: Evaluating Your Draft

- 5.1.2: Reorganizing Your Draft

- 5.1.3: Adding to Your Draft

- 5.1.4: Trimming Your Draft

5.1.1: Evaluating Your Draft

When considering how your draft meets the objectives you set out to achieve at the outset, use a few different lenses to assess that achievement. Each lens corresponds to a step in the drafting process, as shown in the table below.

| Evaluate for | Corresponding Step in the Drafting Process |

|---|---|

| 1. Content | Laying down content in the researching stage (Chapter 3) |

| 2. Organization | Organizing that material (§4.1–§4.2) |

| 3. Style | Stylizing it into effective sentences and paragraphs (§4.3, §4.4, §4.5) |

| 4. Readability | Adding document design features (§4.6) |

Table 5.1.1: Evaluation Lenses and Corresponding Steps in the Drafting Process

Approaching the text critically as if you were the reader you’re catering to—not as the words’ sentimental and protective parent—means keeping the most effective and clear concepts and assuring they flow together into a cohesive narrative.

When evaluating for content, consider what your audience needs to see for understanding the topic. Ask yourself if your coverage is thorough or if you’ve left gaps that would confuse your target audience. Do any concepts need further explanation? Less? With constraints on the length and scope of your document in mind, consider if there are digressions present that would send your reader down off-topic dead ends. Have you given your audience more than what they need? Will your document overwhelm them? Finally, have you fact-checked all of your information to ensure that it is true and accurately cited?

When evaluating for organization, consider the flow of content to determine if the document leads the reader through to the intended understanding of the topic. Is it clear that you’re taking the direct approach by getting right to the point when you need to do so, or is it obvious that you’re taking the indirect approach as necessary? Would it be clear to your reader what organizing principle you’ve followed? When you outlined your draft, you did so from a preliminary understanding of your topic. As you have drafted your message, do you see that something you first thought made sense near the end of your draft makes more sense at the beginning? Shifting paragraphs around for flow is a part of the editing process that will assure related concepts are close.

When evaluating for style, again consider your audience’s needs, expectations, and abilities. Did you draft in an informal style but now realize that a slightly more formal style is more appropriate or vice versa? If you produced a 6 Cs style rubric for Exercise #1 at the end of §4.5.3, apply it now to your draft to determine if it meets audience expectations in terms of its clarity, conciseness, coherence, correctness, courtesy, and confidence. Now would also be a great time to assess whether your style is consistent or whether you started off formal but then lapsed into informality or vice versa.

When evaluating for readability, consider your audience’s needs in terms of the many features that frame and divide the text so that your reader doesn’t get lost, confused, overwhelmed, repulsed, or bored. Check for whether you can do the following:

- Clarify titles

- Add headings or subheadings to break up large chunks of text

- Use lists to enable readers to skim over several items

- Add visuals to complement your written descriptions

The conclusions you draw from these evaluations will help inform and motivate you toward the substantial revisions explained below.

5.1.2: Reorganizing Your Draft

When you first move into a new apartment or house, you have a general idea of where all your furniture should go based on where it was in your previous place. After a few days, however, you may realize that the old arrangement doesn’t make as much sense in the new layout. A new arrangement would be much more practical. The same is true of your document’s organization once you’ve completed a working draft. You may realize that your original outline plan doesn’t flow as well as you thought it would now that you’ve learned more about the topic in the process of writing on it.

Moving pieces around is as easy as highlighting, copying (Ctrl c), cutting (Ctrl x), and pasting (Ctrl v) into new positions. When moving a whole paragraph or more, however, ensure coherence by rewriting the transitional element in the concluding sentence of the paragraph above the relocated paragraph so that it properly bridges to the newly located topic sentence below it. Likewise, the relocated paragraph’s (or paragraphs’) concluding sentence must transition properly to the new topic sentence below it. Additionally, any elements within the relocated text that assume knowledge of what came just before such as abbreviations (e.g., ADA) that the reader hasn’t seen fully spelled out yet must be fully spelled out here and can be abbreviated later in the text.

5.1.3:Adding to Your Draft

In furnishing your new apartment or house, especially if it’s larger than what you had before, you’ll find that merely transplanting your old furniture isn’t enough. The new space now has gaps that need to be filled—a chair here, a couch there, perhaps a rug to tie the whole room together. Likewise, you’ll find when writing a document that gaps need to be filled with more detail. Knowing your organizing principles well is helpful here. If you’re explaining a procedure in a chronological sequence of steps, for instance, you may find that one of the steps you describe involves a whole other sequence of steps that you’re sure your audience won’t know. In this case, embedding the additional sequence using a sub-list numbered with roman numerals (if you used Arabic numerals in the main list) completes the explanation. Of course, keep in mind any stated maximum word or page requirements in case your document exceeds the acceptable range. If it does, then you must be ruthless about chopping anything unnecessary out of your draft.

5.1.4: Trimming Your Draft

As #2 in the 6 Cs of good writing, conciseness means using the fewest words possible to achieve the goal of communication, which is for your reader to understand your intended meaning. Many college students who stretched out their words to reach 1,000-word essays are relieved to find that college and professional audiences prefer writing that is as terse as a text. Indeed, because typing with thumbs is inefficient compared with 10 fingers on a keyboard and no one wants to read more than they must on a little screen, texting helps teach conciseness. Although professional writing requires a higher quality of writing than friends require of texts, the audience expectations are the same. The more succinct your writing is without compromising clarity, the more your reader will appreciate your writing. Given the choice between an article of 500 words and one of 250 that says the same thing, any reader would prefer the 250-word version. We all have better things to do in our jobs than read long-winded blather. Anything that doesn’t contribute to the purpose of your message or document as you conceived it back in Step 1.1 of the writing process must go.

The first trick to paring down your writing is to really want to make every word count and to see excess words as grotesque indulgence. So, pretend that words are expensive. If you had to pay a cent of your own money for every character you wrote in a document that you had to print 1,000 copies of, you would surely adopt a frugal writing style. You would then see that adding unnecessary words is doubly wasteful because time is money. Time spent writing or reading tiresome pap is time you and your reader could spend making money doing other things. Terse, to-the-point writing is both easier to write and easier to read than insufferable rambling. After putting yourself in a frugal frame of mind that detests an excessively wordy style, follow the practical advice in the subsections below to trim your writing effectively.

1. Mass-delete Whatever Doesn’t Belong

The first practical step toward trimming your document is a large-scale purge of whatever doesn’t contribute to the purpose you set out to achieve. The order is important because you don’t want to do any fine-tooth-comb proof-editing on anything that you’re just going to delete anyway. This is probably the most difficult action to follow through on because it means deleting large swaths of writing that may have taken some time and effort to compose. You may even have enjoyed writing them because they’re on quite interesting sub-topics. If they sidetrack readers, whose understanding of the topic would be unaffected (at best) or (worst) overwhelmed by their inclusion, those sentences, paragraphs, and even whole sections simply must go. Perhaps save them in an “outtakes” document if you think you can use them elsewhere. Otherwise, like those who declutter their apartment after reading Marie Kondo’s The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up (2014), the release that follows such a purge can feel something like enlightenment. Highlight, delete, and don’t look back.

2. Delete Long Lead-ins

The next-biggest savings come from deleting lead-ins that you wrote to gear up toward your main point. In ordinary speech, we use lead-ins as something like throat-clearing exercises. In writing, however, these are useless at best because they state the obvious. At worst, lead-ins immediately repulse the reader by signaling that the rest of the message will contain some time-wasting verbiage. If you see the following crossed-out expressions or anything like them in your writing, just delete them:

I’m Jerry Mulligan and I’m writing this email to ask you toplease consider my application for a co-op position at your firm.You may be interested to know thatyou can now find the updated form in the company shared drive.To conclude this memo,we recommend a cautious approach to using emojis when texting clients, and only after they’ve done so first themselves.

In the first example, the recipient sees the name of the sender before even opening their email. It’s therefore redundant for the sender to introduce themselves by name and say that they wrote this email. Likewise, in the third example, the reader can see that this is the conclusion if it’s the last paragraph, especially if it comes below the heading “Conclusion.” In each case, the sentence really begins after these lead-in expressions, and the reader misses nothing in their absence. Delete them.

3. Pare Down Unnecessarily Wordy Phrases

We habitually sprinkle long stock phrases into everyday speech because they sound fancy merely because they’re long and sometimes old-fashioned, as if length and long-time use grants respectability (it doesn’t). These phrases look ridiculously cumbersome when seen next to their more concise equivalent words and phrases, as you can see in Table 5.1.4.3 below. Unless you have good reason to do otherwise, always replace the former with the latter in your writing.

| Replace These Wordy Phrases | with These Concise Equivalents |

|---|---|

| at this present moment in time | now |

| in any way, shape, or form | in any way |

| pursuant to your request | as requested |

| thanking you in advance | thank you |

| in addition to the above | also |

| in spite of the fact that | even though / although |

| in view of the fact that | because/since |

| are of the opinion that | believe that / think that |

| afford an opportunity | allow |

| despite the fact that | though |

| during the time that | while |

| due to the fact that | because/since |

| at a later date/time | later |

| until such time as | until |

| in the near future | soon |

| fully cognizant of | aware of |

| in the event that | if |

| for the period of | for |

| attached hereto | attached |

| each and every | all |

| in as much as | because/since |

| more or less | about |

| feel free to | please |

Table 5.1.4.3: Replace Unnecessarily Wordy Phrases with 1–2 Word Equivalents

Again, the reader misses nothing if you use the words and phrases in the second column above instead of those in the first. Also, concise writing is more accessible to readers who are learning English as an additional language.

4. Delete Redundant Words

Like the wordy expressions in Table 5.1.4.3 above, our speech is also riddled with redundant words tacked on unnecessarily in stock expressions. These prefabricated phrases strung mindlessly together aren’t so bad when spoken because talk is cheap. In writing, however, which should be considered expensive, they make the author look like an irresponsible heavy spender. Be on the lookout for the expressions below so that you are in command of your language. Simply delete the crossed-out words if they appear in combination with the other words:

absolutelyessential (You can’t get any more essential than essential)futureplans (Are you going to make plans about the past? Plans are always future)- small

in size(The context will determine that you mean small in size, quantity, etc.) - refer

backto in orderto (Only use “in order” if it helps distinguish an infinitive phrase, which begins with “to,” from the preposition “to” appearing close to it)- each

and everyoreach andevery (or just “all,” as we saw in Table 5.1.4.3 above) - repeat

again(Is this déjà vu?)

5. Delete Filler Expressions and Words

If you audio-record your conversations and make a transcript of just the words themselves, you’ll find an abundance of filler words and expressions that you could do without and your sentences would still mean the same thing. A few common ones that appear at the beginning of sentences are “There is,” “There are,” and “It is,” which must be followed by a relative clause starting with the relative pronoun that or who. Consider the following, for example:

- There are many who want to take your place.

- Many want to take your place.

- There is nothing you can do about it.

- You can do nothing about it.

- It is the software that keeps making the error.

- The software keeps erring.

In the first and third cases, you can simply delete “There are” and “It is,” as well as the relative pronouns “who” and “that,” respectively, leaving the sentence perfectly fine without them. In the second case, deleting “There is” requires slightly reorganizing the word order but otherwise requires no additional words to say the very same thing. In each case, you save two or three words that simply don’t need to be there.

Other common filler words include the articles a, an, and the, especially in combination with the preposition of. You can eliminate many instances of of the simply by deleting them and flipping the order of the nouns on either side of them.

- technology of the future

- future technology

Obviously, you can’t do this in all cases (e.g., changing “first of the month” to “month first” makes no sense). When proofreading, however, just be on the lookout for instances where you can.

The definite article preceding plural nouns is also an easy target. Try deleting the article to see if the sentence still makes sense without it.

- The shareholders unanimously supported the initiative.

- Shareholders unanimously supported the initiative.

Though the above excess words seem insignificant on their own, they bulk up the total word count unnecessarily when used in combination throughout a large document. They are like dog food fillers such as “powdered cellulose” (a.k.a. sawdust). They provide no nutritive value, but manufacturers add them to charge you more for the mere volume they add to the product. Please don’t cut your writing with filler.

6. Delete Needless Adverbs

Streamline your writing by purging the filler adverbs that you pepper your conversational speech with. In writing, these add little meaning. Recall that adverbs are words that explain verbs (like adjectives do nouns) and typically, but not always, end in -ly. Some of the most common intensifying adverbs include the following:

- actually

- basically

- completely

- definitely

- extremely

- fairly

- fully

- greatly

- hugely

- literally

- quite

- rather

- really

- somewhat

- terribly

- totally

- very

- wholly

Perhaps the worst offender in recent years has been literally, which people overuse and often misuse when they mean “figuratively” or even “extremely,” especially when exaggerating. Saying, “I’ve literally told you a million times not to exaggerate” misuses literally (albeit ironically in this case) because telling someone not to exaggerate a million times would literally take about 20 days if you did nothing but repeat the phrase constantly all day every day without sleeping. That’s not going to happen. If you say, “I’m literally crazy for your speaking style,” you just mean “I’m thrilled by your speaking style.” Using “literally” in this case is just babbling nonsense.

If you find yourself slipping in any of the above adverbs in your writing, question whether they need to be there. (In the case of the previous sentence, leaving out “really” before “need” doesn’t diminish the impact of the statement much.) Consider the following sentence:

- Basically, you can’t really do much to fully eliminate bad ideas because they’re quite common.

- You can’t do much to eliminate bad ideas because they’re so common.

7. Favor Short, Plain Words and Use Jargon Selectively

If you pretend that every character in each word you write costs money from your own pocket, you would do what readers prefer: use shorter words. The beauty of plain words is that they are more understandable and draw less attention to themselves than big, fancy words while still getting the point across. This is especially true when your audience includes ESL readers. Choosing shorter words is easy because they are often the first that come to mind, so writing in plain language saves you time in having to look up and use bigger words unnecessarily. It also involves vigilance in opting for shorter words if longer jargon words come to mind first.

Obviously, you would use jargon for precision when appropriate for your audience’s needs and your own. You would use the word “photosynthesis,” for instance, if (1) you needed to refer to the process by which plants convert solar energy into sugars and (2) you know your audience knows what the word means. In this case, using the big, fancy jargon word achieves a net savings in the number of characters because it’s the most precise term for a process that otherwise needs several words. Using jargon words merely to extend the number of characters, however, is a desperate-looking move that your instructors and professional audiences will see through as a time-wasting smokescreen for a lack of quality ideas.

Table 5.1.4.7 below lists several polysyllabic words (those having more than one syllable) that writers often use when a shorter, more plain and familiar word will do just as well. There’s a time and place for fancier words, such as when formality is required, but in routine writing situations where there’s no need for them, always opt for the simple, one- or two-syllable word.

| Big, Fancy Words | Short, Plain Options |

|---|---|

| advantageous | helpful |

| ameliorate | improve |

| cognizant | aware |

| commence | begin, start |

| consolidate | combine |

| deleterious | harmful |

| demonstrate | show |

| disseminate | issue, send |

| endeavor | try |

| erroneous | wrong |

| expeditious | fast |

| facilitate | ease, help |

| implement | carry out |

| inception | start |

| leverage | use |

| optimize | perfect |

| proficiencies | skills |

| proximity | near |

| regarding | about |

| subsequent | later |

| utilize | use |

Table 5.1.4.7: Favor Plain, Simple Words over Polysyllabic Words

Source: Brockway (2015)

The longer words in the above table tend to come from the Greek and Latin side of the English language’s parentage, whereas the shorter words come from the Anglo-Saxon (Germanic) side. When toddlers begin speaking English, they use Anglo-Saxon-derived words because they’re easier to master and therefore recognize them as plain, simple words throughout their adult lives.

Avoid using longer words when they are grammatically incorrect. For instance, using reflexive pronouns such as “myself” just because it sounds fancy instead looks foolish when the subject pronoun “I” or object pronoun “me” are correct.

- Aaron and myself will do the heavy lifting on this project.

- Aaron and I will do the heavy lifting on this project.

- I’m grateful that you contacted myself for this opportunity.

- I’m grateful that you contacted me for this opportunity.

The same goes for misusing the other reflexive pronouns “yourself” instead of “you,” “himself” or “herself” instead of “him” or “her,” etc.

Sometimes, you see short words rarely used in conversation being used in writing to appear fancy, but they just look pretentious, such as “said” preceding a noun.

- Call me if you are confused by anything in the said contract.

- Call me if you are confused by anything in the contract.

Usually, the context helps determine that the noun following “said” is the one mentioned earlier, making “said” an unnecessary, pompous add-on. Delete it or use the demonstrative pronouns “this” or “that” if necessary to avoid confusion.

Finally, don’t fall into the trap of thinking that a simple style is the same as being simplistic. Good writing can communicate complex ideas in simple words just like bad writing can communicate simple ideas with overly complex words. The job of the writer in professional situations is to make smart things sound simple. Be wary of writing that makes simple things sound complex. You probably don’t want what it’s selling.

8. Simplify Verbs

Yet another way that people overcomplicate their writing involves expressing the action in as many words as possible, such as by using the passive voice, continuous tenses, and nominalizations. We’ve already seen how the passive voice rearranges the standard subject-verb-object word order so that, by going object-verb-subject, an auxiliary verb (form of the verb to be) and the preposition by must be added to say what an active-voice sentence says without them. Consider the following sentences, for instance:

- The candidate cannot be supported by our membership.

- Our members cannot support the candidate.

Here, the active-voice construction on the right uses two fewer words to say the same thing. Though we saw in §4.3.4 that there certainly are legitimate uses of the passive voice, overusing the passive voice sounds unnatural and appears as an attempt to extend the word count or sound more fancy and objective. Because the passive voice is either more wordy or more vague than the active voice, however, readers prefer the latter most of the time and so should you.

Another common annoyance to busy readers is using continuous verb forms instead of simple ones. The continuous verb form uses the participle form of the main verb, which means adding an -ing ending to it, and adds an auxiliary verb (form of the verb to be, which differs according to the person and number) to determine the tense (past, past perfect, present, future, future perfect, etc.). In the table below, you can see how cumbersome continuous forms are compared with simple ones.

| Continuous Verb Forms | Simple Verb Forms |

|---|---|

| I was writing a letter to her. | I wrote a letter to her. |

| I had been writing a letter to her. | I had written a letter to her. |

| I have been writing a letter to her. | I have written a letter to her. |

| I would have been writing a letter to her. | I would have written a letter to her. |

| I am writing a letter to her. | I write a letter to her. |

| I would be writing a letter to her. | I would write a letter to her. |

| I will be writing a letter to her. | I will write a letter to her. |

| I will have been writing a letter to her. | I will have written a letter to her. |

Table 5.1.4.8: Favor Simple Verb Forms Instead of Continuous Forms

There are certainly legitimate reasons for using continuous verb forms to describe actions stretching out over time. In the case of the present tense, saying, “I am considering my options” is more appropriate compared with “I consider my options” because you really are in the process of considering your options. In other tenses, however, people who use word-count-extending strategies favor continuous verb forms because they think those forms sound fancier. Overused or misused, however, such verb forms just annoy the reader by overcomplicating the language.

Yet another strategy for extending the word count with verbs is to turn the main action they describe into nouns, a process called nominalization. This involves taking a verb and adding a suffix such as -ant, -ent, -ion, -tion, -sion, -ence, -ance, or -ing, as well as adding forms of other verbs, such as to make or to give. Nominalization may also require determiners such as articles (the, a, or an) before the action nouns. Consider the following comparisons of nominalized-verb sentences with simplified verb forms:

- The committee had a discussion about the new budget constraints.

- The committee discussed the new budget constraints.

- We will make a recommendation to proceed with the investment option.

- We will recommend proceeding with the investment option.

- They handed down a judgment that the offer wasn’t worth their time.

- They judged that the offer wasn’t worth their time.

- The regulator will grant approval of the new process within the week.

- The regulator will approve the new process within the week.

- He always gives me advice on what to say to the media.

- He always advises me on what to say to the media.

- She’s giving your application a pass because of all the errors in it.

- She’s passing on your application because of all the errors in it.

You can tell that the above sentences where the simple verb drives the action are punchier and have greater impact than those that turn the action into a noun and thus require more words to say the same thing. Indeed, each of the verb-complicating, word-count-extending strategies throughout this subsection is bad enough on its own. Writing riddled with nominalization, continuous verb forms, and passive-voice verb constructions muddies writing with an insufferable multitude of unnecessary words.

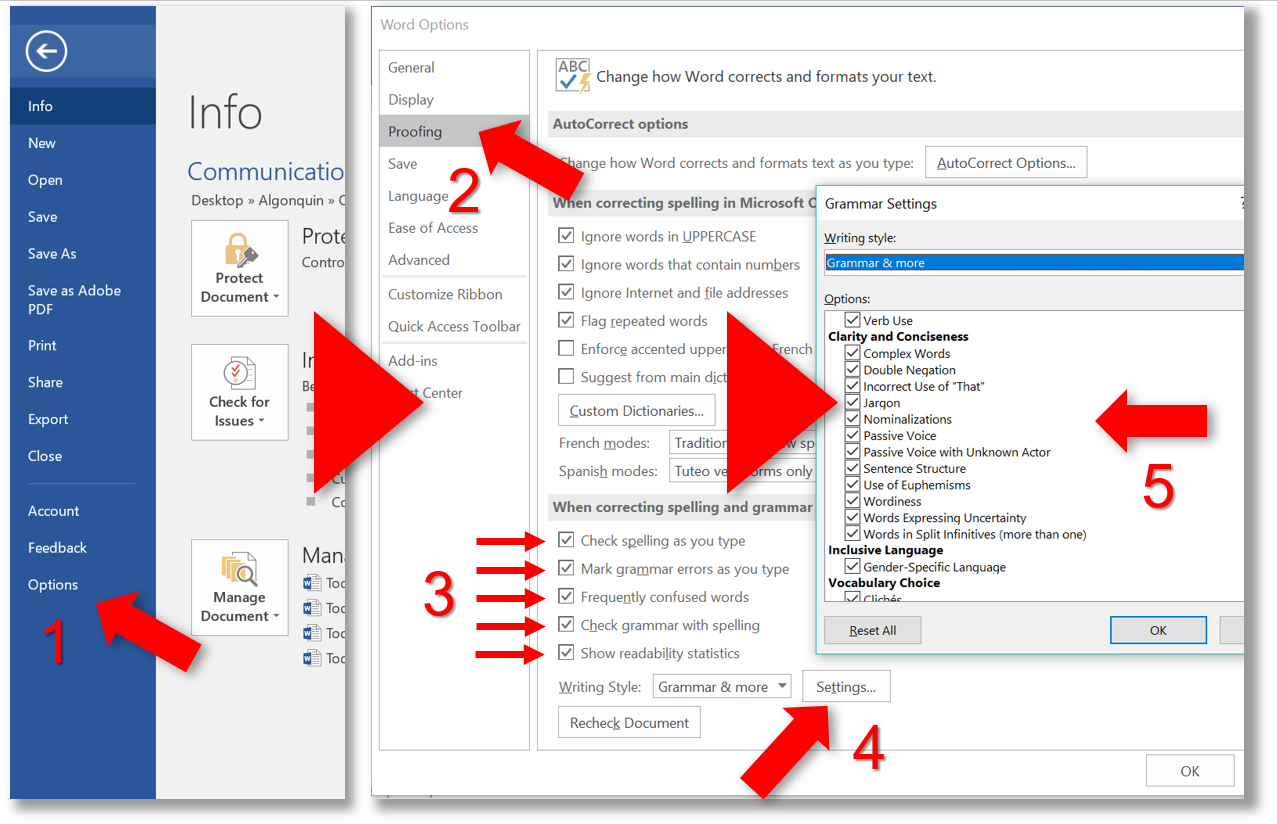

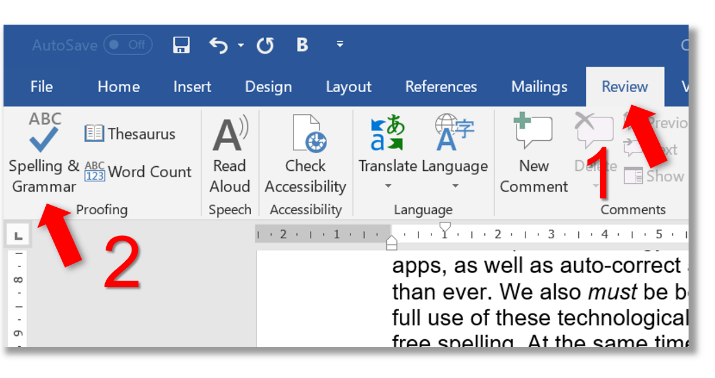

The final trick to making your writing more concise is the Editor feature in your word processor. In Microsoft Word, for instance, you can set up the Spelling & Grammar checker to scan for all the problems above by following the procedure below:

- Go to File (Alt + f) and, in the File menu, click on Options (at the bottom; Alt + t) to open the Word Options control panel.

- Click on Proofing in the Word Options control panel.

- Check all the boxes in the “When correcting spelling and grammar in Word” section of the Word Options control panel.

- Click on the Settings… button beside “Writing Style” under the check boxes to open the Grammar Settings control panel.

- Click on all the check boxes in the Grammar Settings control panel, as well as the Okay button of both this panel and the Word Options panel to activate.

Figure 5.1.4.8: Setting up your MS Word Grammar, Style, and Spellchecker - Go to the Review menu tab in the tool ribbon at the top of the Word screen and select Spelling & Grammar (Alt + r, s) to activate the Editor that will, besides checking for spelling and grammar errors, also check for all of the stylistic errors you checked boxes for in the Grammar Settings control panel.

When you finish running your grammar, style, and spellchecker through your document, a dialog box will appear showing readability statistics. Pay close attention to stats such as the average number of words per sentence and letters per word. If the former exceeds thirty and the latter ten, your writing might pose significant challenges to some readers, especially ESL. Do them a solid favor by breaking up your sentences and simplifying your word choices.

Rather than suck the life out of language by adding useless verbiage, make your writing like a paperclip. A paperclip is beautiful in its elegance. It’s so simple in its construction and yet does its job of holding paper together perfectly without any extra parts or mechanisms like staples that need to fasten pages together and unfasten them. A paperclip does it with just a couple of inches of thin, machine-bent wire. We should all aspire to make our language as elegant as a paperclip so that we can live a life free of time-wasting writing.

Key Takeaway

egin editing any document by evaluating it for the quality of its content, organization, style, and readability, then add to, reorganize, and trim it as necessary to meet the needs of the target audience.

Exercises

- Take any writing assignment you’ve previously submitted for another course, ideally one that you did some time ago so that it almost seems like it was written by another person. Evaluate and comment on its content, organization, style, and readability. Explain how you can improve it from each of these perspectives. Add to that assignment anything that would help the target audience understand it better. Trim that assignment using the eight strategies explained in §5.1.4 above.

- What are some ways you can detail the differences between formal and informal writing? Make a list of three notable ways you can determine if an article or text has been written for an audience of scholars or a group of friends. What forms of communication tend to be less formal?

Reference

Brockway, L. H. (2015, November 3). 24 complex words—and their simpler alternative. Retrieved from https://www.prdaily.com/24-complex-words-and-their-simpler-alternatives/

5.2: Proofreading for Grammar

Section 5.2 Learning Objectives

- Identify and correct sentence errors such as comma splices, run-ons, and fragments.

- Identify and correct grammatical errors such as subject-verb and pronoun-antecedent disagreement, as well as faulty parallelism.

- Identify and correct syntax errors such as misplaced modifiers.

- Plan, write, revise, and edit short documents and messages that are organized, complete, and tailored to specific audiences.

Grammar organizes the relationships between words in a sentence, especially between the doer and action, so that the reader can understand in detail who’s doing what. When you botch those connections with grammar errors, however, you risk confusing the reader. Severe errors force the reader to interpret what you meant. If the reader then acts on an interpretation different from the meaning you intended, major consequences can ensue, including expensive damage control. You can avoid being a liability and embarrassing yourself by following some simple rules for how to structure your sentences grammatically. By following these rules habitually, especially when you apply them at the proofreading stage, not only will your writing be clearer to the reader and better organized, but your thought process may become more organized as well.

5.2.1: Sentence Errors

Readers who find comma splices, fragments, and run-on sentences lose confidence in the writer’s command of language and thus the quality of their work. Such giveaways suggest that the writer doesn’t know much about sentence structure and punctuation. This is especially bad coming from native English speakers in their 20s or older because it says that they still don’t understand the basics of their own written language even after decades of using it. It’s important to know what to look for, then, when proofreading your draft for sentence errors.

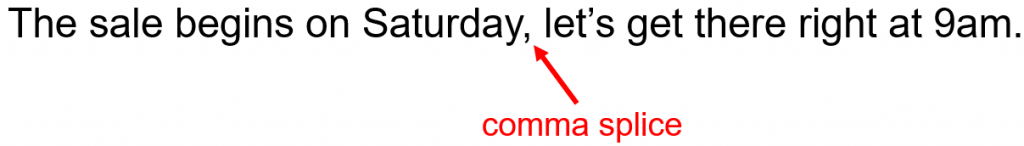

1. Comma Splices

A comma splice is simply two independent clauses separated by only a comma. Perhaps the error comes from writers thinking that, because the two clauses say closely related things, they need something a little “lighter” than a period to separate them. While separating them with a comma is certainly possible, doing so with a comma alone shows that the writer doesn’t fully understand what a sentence is and what commas do.

Spotting a comma splice requires being able to identify an independent clause—that is, the combination of a subject and predicate (noun + verb) that can stand on its own as a sentence. In the Figure 5.2.1.1 example above, the first independent clause’s subject is “The sale” and its predicate is “begins on Saturday” (sale + begins), so it can stand on its own as a sentence if it ended with a period. The second is an imperative clause with the main verb being “let,” so it too can stand on its own as a sentence. When proofreading, be on the lookout for commas that have independent clauses on either side—that is, clauses that can stand on their own as sentences.

Fixing a comma splice is as easy as swapping out the comma for the correct punctuation or adding a conjunction, depending on the relationship you want to express between the two clauses. Altogether, you have four options in correcting a comma splice—two that replace the comma with other punctuation and two that leave it as-is but add a conjunction:

- Replace the comma with a period to turn the two independent clauses into two sentences if each is a distinct enough complete thought. Don’t forget to capitalize the letter that followed the comma. Correcting the comma splice in the Figure 5.2.1.1 example would look as follows:

- The sale begins on Saturday. Let’s get there at 9 a.m.

- Replace the comma with a semicolon to form a compound sentence if the two independent clauses are related enough to be in the same sentence:

- The sale begins on Saturday; let’s get there at 9 a.m.

If the writer wanted something a little lighter than a period to separate the two clauses, then a semicolon fits the bill.

- Add a coordinating conjunction (e.g., and, but, so; see Table 4.3.2a for all seven of them) to form a compound sentence if it clarifies the relationship between the independent clauses:

- The sale begins on Saturday, so let’s get there at 9 a.m.

Note that if you see three or more independent clauses with commas between them and an and or or before the last one, then it’s a perfectly correct (albeit probably too long) compound sentence that combines whole clauses rather than just nouns or verbs. See the final example given in Comma Rule 4 below for a sentence organized into a list of clauses.

- Add a subordinating conjunction (e.g., when, if, though, etc.; see Table 4.3.2a for more) to form a complex sentence (see Table 4.3.2b for more on complex sentences):

- When the sale begins on Saturday, let’s get there at 9 a.m.

Though each of the above comma-splice fixes is grammatically correct, the last two are best because adding a conjunction clarifies the relationship between the ideas expressed in the two clauses.

A common comma-splice error involves “however” following a comma that separates two independent clauses. Consider the following sentences that are grammatically equivalent:

- The company raised its rates, however, we were granted an exemption.

- = The company raised its rates, however we were granted an exemption.

- = The company raised its rates, we were granted an exemption.

Seeing that you have independent clauses on either side of the comma preceding “however” is easier if you imagine the sentence without both “however” and the comma following it, as in the third example sentence above. Fixing the error is as easy as replacing the comma preceding “however” with a semicolon and ensuring that a comma follows “however,” which is a conjunctive adverb (see Comma Rule 2 below):

- The company raised its rates; however, we were granted an exemption.

This is somewhat tricky because “however” can be surrounded by commas if it’s used as an interjection between the subject and predicate (see Comma Rule 3 below) or between clauses in a complex sentence:

- This particular company, however, had been delaying raising its rates for years.

- With the company raising its rates, however, we had to apply for an exemption.

Because you see the first clause beginning with “With” in the second example, you know that it’s a dependent clause that will end with a comma followed by the main clause. It’s thus possible to add “however” where the comma separates the subordinate from the main clause.

When proofreading, be on the lookout for “however” surrounded by commas. If the clauses on either side can stand on their own as sentences, fix the comma splice easily by replacing the first comma with a semicolon. If one of the clauses before or after is a subordinate clause and the other a main clause, however, then you’re safe (as in this sentence). For more on comma splices, see the following resources:

- Run-on Sentences and Comma Splices (Purdue OWL)

- Fixing Comma Splices (Plotnick, 2003)

2. Run-on Sentences

Whereas a comma splice places the wrong punctuation between independent clauses, a run-on (a.k.a. fused) sentence simply omits punctuation between them. Perhaps this comes from the second clause following the first so closely in the writer’s free-flowing stream of consciousness that they don’t think any punctuation is necessary between them. While it may be clear to the writer where one idea-clause ends and the other begins, that division isn’t so clear to the reader. The absence of punctuation will cause them to trip up, and they’re forced to mentally insert the proper punctuation to make sense of it, which is frustrating.

Spotting a run-on is easy if it’s just commas missing before coordinating conjunctions. If you string together the last couple of sentences concluding the above paragraph, for instance, and use conjunctions to separate the four clauses without accompanying commas, you’ll get a cumbersome run-on:

- That division isn’t so clear to the reader and the absence of punctuation will cause them to trip up and they’re forced to mentally insert the proper punctuation to make sense of it and that’s frustrating.

“Run-on” is a good description for sentences like this because they seem like they can just go on forever like a toddler tacking on clause after clause using coordinating conjunctions (… and … and … and …). Though the above sentence would be perfectly correct if commas preceded “and” and “so,” adding further clauses would just exhaust the reader’s patience, commas or no commas. A run-on is not necessarily the same as a long sentence. Such a long sentence can become convoluted, however, especially for audiences who may struggle with English, such as ESL learners.

Sometimes spotting a run-on is just a matter of tripping over its nonsense. Say you’re reading your draft and then come across the following sentence:

- We’ll have to drive the station is too far away to get there on foot.

You’re doing just fine reading this sentence up until the word “is,” since, the way things were going, you probably expected a vehicle to follow the article “the.” Assuming “drive” is being used as a transitive verb (Simmons, 2007) that takes an object, “station wagon” would make sense. When you see “is” instead of “wagon,” however, you might go back and see if the writer forgot to put “to” before “station” to make “drive to the station.” That doesn’t make sense either, however, given what follows. Finally, you realize that you’re really dealing with two distinct independent clauses starting with a short one and that some punctuation is missing after “drive.” The sentence is like a chain with a broken link.

Once you’ve found that missing link, fixing a run-on is just a simple matter of adding the correct punctuation and perhaps a conjunction, depending on the relationship between the clauses. Indeed, the options for fixing a run-on are identical to those for fixing a comma splice. Following the same menu of options as those presented above, you would be correct doing any of the following:

- Add a period between the clauses (after “drive”) and capitalize “the” to form two sentences:

- We’ll have to drive. The station is too far away to get there on foot.

- Add a semicolon between the clauses to form a compound sentence:

- We’ll have to drive; the station is too far away to get there on foot.

This is the easiest, quickest fix of them all.

- Add a comma and coordinating conjunction to form a compound sentence:

- We’ll have to drive, for the station is too far away to get there on foot.

- Add a subordinating conjunction to form a complex sentence:

- We’ll have to drive because the station is too far away to get there on foot.

Again, though each of the above run-on fixes is grammatically correct, only the last one best clarifies the relationship between the ideas expressed in the two clauses. For more on run-on sentences, see the following:

- Run-on Sentences and Comma Splices (Purdue OWL, n.d.)

3. Sentence Fragments

A sentence fragment is one that’s incomplete usually because either the main-clause subject, predicate, or both are missing. The most common sentence fragment is the latter, where a subordinate clause poses as a sentence on its own, usually with its main clause being the preceding or following sentence. If the final example in §5.2.1.2 above were a fragment, it would look like the following:

- We’ll have to drive. Because the station is too far away to get there on foot.

Recall that a complex sentence combines a main (a.k.a. independent) clause with a subordinate (a.k.a. dependent) clause, and the cue for the latter is that it begins with a subordinating conjunction (see Table 4.3.2a for several examples). In the above case, the coordinating conjunction “because” makes the clause subordinate, which must join with a main clause in the same sentence to be complete.

The fix is simply to join the fragment subordinate clause with its main clause nearby so that they’re in the same sentence. You can do this in one of two ways, either of which is perfectly correct:

- Delete the period between the sentences and make the subordinating conjunction lowercase if the subordinate clause follows the main clause:

- We’ll have to drive because the station is too far away to get there on foot.

- Move the subordinate clause so that it precedes the main clause, separate the two with a comma, and make the first letter of the main clause lowercase:

- Because the station is too far away to get there on foot, we’ll have to drive.

The same applies to sentences that begin with any of the seven coordinating conjunctions. These are technically fragments but can be easily fixed by joining them with the previous sentence to make a compound. You could also change the conjunction to something else, such as a conjunctive adverb like “However” for “but” or “Also” for “and” followed by a comma:

- The station is too far away to get there on foot. But we’ll drive.

- The station is too far away to get there on foot, but we’ll drive.

- The station is too far away to get there on foot. However, we’ll drive.

You may also encounter fragments that are just noun phrases, verb phrases, prepositional phrases, and so on. Of course, we speak often in fragments rather than full sentences, so if we’re writing informally, such fragments are perfectly acceptable. Even in some formal documents, such as résumés, fragments are expected in certain locations such as the Objective statement (an infinitive phrase) and profile paragraph (noun phrases) and in the Qualifications Summary.

If we’re writing formally, however, these fragmentary phrases are variations on the error of leaving sentences incomplete. The easy fix is always to re-unite them with a proper sentence or to make them into one by adding parts.

- We thank you for choosing our company. As well as the impressive initiative you’ve taken.

- We thank you for choosing our company and are impressed by the initiative you’ve taken.

- We thank you for choosing our company. You’ve shown impressive initiative.

The beauty of the English language is that there’s an endless number of ways to say something and still be grammatically correct as long as you know what makes a proper sentence. If you don’t, review §4.3.1 and §4.3.2 till you can spot the main subject noun and verb in any sentence, as well as tell if they’re missing. For more on fragments, see the following:

- Sentence Fragments (Purdue OWL, n.d.)

For exercises in spotting and fixing comma splices, run-ons, and fragments, see the digital activities at the bottom of the Guide to Grammar and Writing pages linked above (Purdue OWL, n.d.), as well as Exercise: Run-ons, Comma Splices, and Fused Sentences (Purdue OWL, n.d.).

5.2.2: Grammar Errors

Let’s focus on some of the most common grammar errors in college and professional writing:

- 5.2.2.1: Subject-verb Disagreement

- 5.2.2.2: Pronoun-antecedent Disagreement

- 5.2.2.3: Faulty Parallelism

- 5.2.2.4: Dangling and Misplaced Modifiers

1. Subject-verb Disagreement

Perhaps the most common grammatical error is subject-verb disagreement, which is when you pair a singular subject noun with a plural verb (usually ending without an s) instead of a singular one (usually ending with an s) or vice versa. Spotting such disagreements of number requires being able to identify the subject noun and main verb of every sentence and hence knowledge of sentence structure. The search for the main subject noun and verb is complicated by the fact that many other nouns and verbs in various phrase types can crowd into a sentence. The following subject-verb agreement rules help you know what to look for.

Quick Rules

Click on the rules below to see further explanations, examples, advice on what to look for when proofreading, and demonstrations of how to correct common subject-verb disagreement errors associated with each one.

Subject-verb Agreement Rule 1.1:

- Singular subjects take singular verbs.

- The first of many cuts is going to be the deepest.

Subject-verb Agreement Rule 1.2:

- The indefinite pronouns each, either, and neither, and those ending with -body or -one take a singular verb.

- If each of you chooses wisely, someone is going to win the prize, but everybody wins because neither really loses.

Subject-verb Agreement Rule 1.3:

- Collective nouns and some irregular nouns with plural endings are singular and take a singular verb.

- The band isn’t going on stage until the news about the stage lighting is more positive.

Subject-verb Agreement Rule 2:

- Plural noun, compound noun, and plural indefinite pronoun subjects take plural verbs.

- The rights of the majority usually trump those of minority groups, except when money and politics conspire, and both usually do.

Subject-verb Agreement Rule 3:

- Compound subjects joined by or or nor take verbs that agree in number with the nouns closest to them.

- Neither your lawyers nor the justice system is going to be able to adequately punish this type of crime.

Subject-verb Agreement Rule 4:

- The verb in clauses beginning with there or here agrees with the subject noun following the verb.

- There are two types of people in the world, and here comes one of them now.

Extended Explanations

Subject-verb Agreement Rule 1.1: Singular subjects take singular verbs.

When the subject of the sentence—the doer of the action—is a singular subject (i.e., one doer), the verb (the action it performs) is always singular. Watch out, though: this rule holds even if phrases modifying the subject or intervening parenthetical elements are plural. You just have to be able to tell that those phrases and parenthetical elements aren’t the main subject and therefore don’t count when determining the number of the verb.

Correct:

- Our investment is paying off nicely.

- Why it’s correct: The singular subject “investment” takes the singular verb “is,” which is the third-person singular form of the verb to be.

Correct:

- The source of all our network errors disappears whenever you do a system restart.

- Why it’s correct: The singular subject “source” takes the singular main verb “disappears”; the plural noun “errors” immediately before the verb is just the last word in a prepositional phrase (“of . . .”) modifying the subject.

Correct:

Stalling for time to think of better responses doesn’t work in a job interview.

Why it’s correct: The singular subject “stalling,” a gerund (action noun), takes the singular main verb “does”; the plural noun “responses” immediately before the verb is just the last word in a prepositional phrase (“of . . .”) embedded in an infinitive phrase (“to think . . .”) embedded in another prepositional phrase (“for . . .”).

Correct:

- The singer-songwriter, along with new additions to her five-piece backup band, arrives at the press conference at 1:30 p.m.

- Why it’s correct: Despite the parenthetical addition of other actors, the grammatical subject (“singer-songwriter”) is still singular and takes a singular verb.

How This Helps the Reader

Following this rule helps the reader connect the doer of the action with the main action itself, especially when a variety of phrases, including nouns of different number, intervene between the subject noun and main verb.

What to Look for When Proofreading

Look for subject nouns (the main doers of the action) and the main verbs that the subject noun takes, then ensure that both are singular. Look out especially for verbs that are wrongly plural in form because the nouns immediately preceding them are plural despite the fact that they are only part of phrases modifying the main subject noun.

Incorrect:

- The best vodka in the opinion of all the experts at international competitions are surprisingly the bottom-shelf Alberta Pure.

The fix:

- The best vodka in the opinion of all the experts at international competitions is surprisingly the bottom-shelf Alberta Pure.

Incorrect:

- The lucky winner, as well as three of their best friends, are going on an all-expenses-paid trip to beautiful Cornwall, Ontario!

The fix:

The lucky winner, as well as three of their best friends, is going on an all-expenses-paid trip to beautiful Cornwall, Ontario!

In the first incorrect example sentence above, the proximity of the plural nouns “experts” and “competitions” to the main verb (form of to be) probably made the writer think that the verb had to be plural, too. The true subject noun of the sentence, however, is “vodka,” which is singular and therefore takes the singular verb “is” no matter what comes between them. In the second incorrect sentence, the grammatical subject is the singular “winner,” so the main verb should be the singular “is,” not the plural “are.” A parenthetical interjection between the subject and the verb, even if it appears to pluralize the subject with “as well as,” “along with,” “plus,” or the like, technically doesn’t make a compound subject (see Rule 2 below for more on compounds).

Subject-verb Agreement Rule 1.2: The indefinite pronouns each, either, neither, and those ending with -body or -one take a singular verb.

When the subject noun of the sentence is the indefinite pronoun either, neither, each, anybody, everybody, nobody, somebody, anyone, everyone, someone, no one, or none (see Table 4.4.2a above on pronouns), it is singular and takes a singular verb.

Correct:

- Each has enough personal finance know-how to handle her own taxes.

- Why it’s correct: The subject pronoun “Each” can be thought of as the singular “Each one” and therefore takes a singular verb. In this case the verb is “has” rather than the plural “have” that would be appropriate if the subject were “All of them.”

Correct:

- Either is fine.

- Why it’s correct: The subject pronoun “Either” can be thought of as the singular “Either one,” despite implying a pair of options, and therefore takes a singular verb—in this case “is.”

Correct:

- “Perhaps none is more vulnerable than James, a soft-spoken 19-year-old who is quick to flash a smile that would melt ice” (Chianello, 2014).

- Why it’s correct: The subject pronoun “none” in this case can be thought of as the singular “no one” because the topic of the sentence concerns a single person. The pronoun therefore takes a singular verb—in this case “is” rather than the plural “are.”

- Exception: None can sometimes be a plural indefinite pronoun depending on what comes later in the sentence.

Correct:

- “None are more hopelessly enslaved than those who falsely believe they are free” (Goethe, 1809, p. 397).

- Why it’s correct: The subject pronoun “none” can be thought of as “no people,” consistent in number with the later pronoun “those,” and thus a plural pronoun that takes a plural verb—in this case “are,” not “is.”

How This Helps the Reader

Following this rule helps the reader see that the “one” or “body” suffix in each of these indefinite pronouns is singular, even if the word applies to many people, and therefore takes a singular verb form.

What to Look for When Proofreading

Look for any indefinite pronouns ending with -one or -body taking a plural main verb and change the verb to the singular form.

Incorrect:

- Everybody here share our opinion on quantitative easing.

- The fix: Everybody here shares our opinion on quantitative easing.

- The fix: All here share our opinion on quantitative easing.

Incorrect:

- Each of you send enough carbon into the atmosphere to poison a river.

- The fix: Each of you sends enough carbon into the atmosphere to poison a river.

- The fix: All of you send enough carbon into the atmosphere to poison a river.

Here, the “every” part of the word everybody in the first incorrect sentence and the fact that the second addresses a group suggests to the confused writer that a plurality of actors is at play, thus requiring the plural verbs “share” and “send.” Wrong! The “body” part of the word is the operative one; being singular, it takes a singular verb—“shares” in this case—and “Each” is short for “Each one.” Another fix in each case is to make the subject the plural “All” and keep the verbs plural.

Subject-verb Agreement Rule 1.3: Collective nouns and some irregular nouns with plural endings are singular and take a singular verb.

Collective nouns such as “group” are grammatically singular and thus take a singular verb despite meaning several people or things. The following are common collective nouns:

- army

- audience

- band

- board

- bundle

- cabinet

- class

- committee

- company

- corporation

- council

- crew

- department

- faculty

- family

- firm

- gang

- group

- jury

- majority

- membership

- minority

- navy

- pack

- party

- plethora

- public

- office

- school

- senate

- society

- task force

- team

- tribe

- troupe

The same is true of any company name that ends in s or has a compound name (e.g., Food Basics, Long & McQuade), as well as any compound of inanimate objects treated as a singular entity (e.g., meat and potatoes is considered one dish; see Rule 2 below for more on compounds). Likewise, some special-case words that look like plurals because they end with s instead take singular pronouns and verbs, especially names for games and disciplines or areas of study, as well as dollar amounts, distances, and amounts of time:

- acoustics

- billiards

- cards

- civics

- crossroads

- darts

- # dollars

- dominoes

- economics

- ethics

- gymnastics

- # hours

- # meters

- linguistics

- mathematics

- measles

- mumps

- news

- physics

- rabies

- shambles

Note that most of these words will be plural if used other than meaning disciplines, fields of study, games, or number of units. For instance, when you’re playing darts, you would use the plural verb in “Three darts remain” to refer to three individual darts in your hand but use a singular verb when saying “Darts is a way of life” because you’re now using “darts” in the sense of the game rather than the object.

Correct:

- The committee demands action on the latest media blunder.

- Why it’s correct: The collective noun “committee” is singular, despite being comprised of several people, and therefore takes the singular verb “demands,” not the plural “demand.”

Correct:

- A demolition crew of three sledgehammer-wielding heavies is leveling the house as we speak.

- Why it’s correct: The collective noun “crew” is singular despite being followed by a prepositional phrase detailing how many people are in the crew. Despite also the plural noun “heavies” preceding the main verb, the singular “is” is the correct verb rather than the plural “are.”

Correct:

- Food Basics has a deal on for ice cream right now, and Dolce & Gabbana has some fresh new styles coming this season.

- Why it’s correct: Though the subject nouns seem plural because one ends with s and the other compounds two names, being a single corporate entity in each case makes them singular and take the singular verb “has” rather than the plural “have.”

Correct:

- Oh look, green eggs and ham is on the menu.

- Why it’s correct: Though the subject noun seems plural because it is a compound of a plural and singular noun, it is considered one singular dish and therefore takes the singular verb “is” rather than the plural “are.”

Correct:

- The news is so depressing today.

- Why it’s correct: Though the subject noun seems plural because it ends with s, “news” is a singular noun taking the singular verb “is,” not the plural “are.”

Correct:

- Ethics isn’t an optional field of study for business professionals.

- Why it’s correct: Though the subject noun seems plural because it ends with s and the singular “ethic” is also a legitimate word, it acts in this case as a singular entity because it is a field of study and therefore takes the singular verb “is.”

Correct:

- Five dollars donated to the right charities is all that’s needed to save a life.

- Why it’s correct: Though the subject noun seems plural because it contains more than one dollar, it acts as a singular entity and thus takes the singular verb “is” regardless of the noun “charities” that comes before it in a prepositional phrase.

Correct:

- Ten kilometers is too far to walk because those ten kilometers are going to make us late.

- Why it’s correct: The first “Ten kilometers” is a grammatically singular subject because the distance as a whole is meant. The second instance refers to each individual kilometer together with the others, however, so it is grammatically plural, taking the plural pronoun “those” and verb “are.”

How This Helps the Reader

Following this rule helps the reader connect the singular grammatical subject performing a single action in concert as one entity with the main verb, especially when phrases of different number come between them.

What to Look for When Proofreading

Look for count nouns, as well as special-case nouns that look plural but are actually singular, such as games and areas of study, like those identified above. Ensure that the main verb following them is singular rather than plural.

Incorrect:

- A pack of lies averaging around twenty per day are winning over a confused and angry swath of the electorate.

- The fix: A pack of lies averaging around twenty per day is winning over a confused and angry swath of the electorate.

Incorrect:

- The acoustics in here are so bad that it makes me want to study acoustics, which are all about how sounds behave in certain environments.

- The fix: The acoustics in here are so bad that it makes me want to study acoustics, which is all about how sounds behave in certain environments.

In the first incorrect sentence above, the collective noun “pack” is grammatically singular and must therefore take the singular verb “is,” not the plural verb “are”, despite it being comprised of a plurality of things (“lies”) identified in the prepositional phrase following it. In the second incorrect sentence, we see two different types of the word “acoustics.” One type means “sound quality,” acts as a plural grammatical subject, and therefore takes the plural verb “are.” The other, meaning the study of how sounds interact with the environment, takes the singular verb “is,” not the plural verb “are.”

Subject-verb Agreement Rule 2: Plural noun, compound noun, and plural indefinite pronoun subjects take plural verbs.

When the subject of the sentence is plural or contains two or more nouns or pronouns joined by and to make a compound subject, the verb describing the action they perform together is always plural regardless of whether the nouns are singular or plural. The verb is plural even if the compounded subject noun closest to the verb is singular. Other word types that take plural pronouns and verbs include:

- The indefinite pronouns both, few, many, several, and others

- Some items that seem singular because they are assembled into one unit, such as binoculars, glasses, jeans, pants, scissors, shears, and shorts

- Sport teams with singular names, such as the Colorado Avalanche and Tampa Bay Lightning

- Bands of musicians with singular-sounding names such as the Tragically Hip and Arcade Fire

Correct:

- Self-driving cars are going to revolutionize more than just the auto industry.

- Why it’s correct: The plural subject noun “cars” takes the plural main verb “are.”

Correct:

- Goodness, we have our work cut out for us.

- Why it’s correct: The plural subject pronoun “we” takes the plural main verb “have”

Correct:

- All the network systems and the mainframe we’ve been updating are going to have to be liquidated now.

- Why it’s correct: The compound subject with the plural noun “systems” and singular noun “mainframe” takes the plural main verb “are.” All the other verbs are part of embedded phrases that don’t affect the verb number.

Correct:

- A few of them say they can’t go, but several are still going.

- Why it’s correct: The plural indefinite pronouns “few” and “several” take the plural verbs “say” and “are,” respectively.

Correct:

- These pants don’t fit, these scissors don’t cut, and these shears are kaput.

- Why it’s correct: Though each of these subject nouns sells as one item, they are considered pairs grammatically and therefore take plural verbs such as “don’t” instead of the singular “doesn’t.”

Correct:

- The Tragically Hip are playing their final concert in Kingston, where they played their first show 32 years earlier.

- Why it’s correct: As a five-piece band of musicians, the Tragically Hip are a grammatically plural noun despite having a singular-sounding name and therefore take the plural verb “are.”

How This Helps the Reader

Following this rule helps the reader connect the doer of the action with the main action itself, especially when a variety of phrases, including nouns of different numbers, intervene between the subject noun and main verb.

What to Look for When Proofreading

Look for subject nouns (the main doers of the action) and the main verbs that the subject noun takes, then ensure that both are plural. Look out especially for compound subjects with a singular noun close to the verb tricking you into making the main verb singular.

Incorrect:

- Most major auto manufacturers and, of course, Tesla is leading the way toward self-driving cars via a switch to all-electric drivetrains.

- The fix: Most major auto manufacturers and, of course, Tesla are leading the way toward self-driving cars via a switch to all-electric drivetrains.

Incorrect:

- I can respect their musicianship, but Rush just annoys me, or maybe it’s just Geddy Lee’s voice.

- The fix: I can respect their musicianship, but Rush just annoy me, or maybe it’s just Geddy Lee’s voice.

In the first incorrect example above, the proximity of the singular noun “Tesla” to the main verb probably made the confused writer think that the verb had to be the singular “is,” too. The subject is in fact a compound, however: “manufacturers and . . . Tesla.” Changing the main verb to a plural form easily fixes the subject-verb disagreement of number.

In the second incorrect example, the band Rush seems like it should be a singular noun and take the singular verb “annoys” because the word rush is singular; as a trio of musicians, however, the band is grammatically plural and takes the plural verb “annoy.” Notice, when we use the noun “band” in front of “Rush” so that “band” is grammatically the subject noun, however, we use a singular verb following Rule 1.3 above.

Subject-verb Agreement Rule 3: Compound subjects joined by or or nor take verbs that agree in number with the nouns closest to them.

When the subject of the sentence is a compound joined by the coordinating conjunction or or nor, the number (singular or plural) of the verb is determined by the subject noun that comes immediately before it.

Correct:

- Either the players or the coach is going to take the fall for the loss.

- Why it’s correct: Though this is a compound subject comprised of the plural “players” and singular “coach,” the main verb is the singular “is” because “or” joins the two subject nouns and the one closest to the verb, “coach,” is singular.

Correct:

- When neither the project lead nor dozens of engineers dare to doubt the safety of the launch, you have all the makings of a Challenger-like disaster.

- Why it’s correct: The plural subject pronoun “dozens,” as the second part of the compound subject including the singular “lead,” takes the plural main verb “dare” because it is closer.

How This Helps the Reader

Following this rule helps the reader see the two compounded subject nouns as separate actors performing the verb action independently of one another rather than together.

What to Look for When Proofreading

Look for plural verbs that disagree in number with singular subject nouns closest to them when the subject nouns are joined by or or nor.

Incorrect:

- A rock or a hard place are your only choice in this situation.

- The fix: A rock or a hard place is your only choice in this situation.

In the incorrect example above, the compounding of the two singular nouns likely made the confused writer think that the verb should be plural as it is when and compounds subject nouns. When or or nor compounds subjects, however, the verb must agree with whatever subject noun comes immediately before it.

Subject-verb Agreement Rule 4: The verb in clauses beginning with there or here agrees with the subject noun following the verb.

When a sentence or clause begins with the pronoun there or here, the subject noun follows the verb and therefore determines whether the verb should be singular or plural. In other words, what comes before the verb usually determines whether the verb is singular or plural, but in this case, what comes after the verb does that. In such expletive constructions, as they’re called, here or there are not actually subjects.

Correct:

- There appears to be a mighty storm approaching on the horizon.

- Why it’s correct: The singular subject noun “storm” following the verb takes the singular verb “appears.”

Correct:

- Here is a pencil and here are some forms you need to fill out.

- Why it’s correct: The singular subject noun “pencil” following the main verb takes the singular verb “is” in the first clause. The plural subject noun “forms” in the second clause takes the plural verb “are.”

Correct:

- There happen to be six conditions on which the growth of our business depends.

- Why it’s correct: The plural subject noun “conditions” following the verb takes the plural verb “happen” rather than the singular “happens.”

Correct:

- There is nothing to the allegations of wrongdoing.

- Why it’s correct: The singular subject noun “nothing” following the verb takes the singular verb “is” regardless of the plural noun “allegations” in the prepositional phrase modifying the subject noun.

Correct:

- There are too many applications to sort through in the given timeframe.

- Why it’s correct: The plural subject noun “applications” following the verb takes the plural verb “are.”

How This Helps the Reader

In sentences beginning with the pronoun there, following this rule cues the reader toward the number of the subject noun before it appears.

What to Look for When Proofreading

Look for sentences or clauses beginning with there and ensure that the verb agrees with the noun that follows it. The verb isn’t necessarily singular just because there comes before the verb (where the subject is usually located) and seems like a singular pronoun.

Incorrect:

- I can’t believe there just happens to be two tickets to the show you wanted to see in my pocket here.

- The fix: I can’t believe there just happen to be two tickets to the show you wanted to see in my pocket here.

Incorrect:

- Here is a bar graph and pie chart you can extrapolate results from.

- The fix: Here are a bar graph and pie chart you can extrapolate results from.

In the first incorrect sentence above, the pronoun “there” is not the subject noun of the relative clause following “that”; the plural noun “tickets” is the subject and therefore takes the plural verb “happen” rather than the singular “happens.” In the second incorrect sentence, the grammatical subject is the compound noun “bar graph and pie chart” following “Here,” so the main verb must be the plural “are,” not the singular “is.”

For more on subject-verb agreement and how to correct disagreement, see the following resources:

- Making Subjects and Verbs Agree (Paiz, Berry, & Brizee, 2018)

- Self Teaching Unit: Subject-Verb Agreement (Benner, 2000), including exercises

2. Pronoun Errors

For more on pronoun-antecedent disagreements of number (e.g., Everybody has an opinion on this, but they are all wrong), ambiguous pronouns (e.g., The plane crashed in the field, but somehow it ended up unscathed—was the plane or field left unscathed?), and pronoun case errors (e.g., Rob and me are going to the bank—would you say “me is going to the bank”?), see the following resource:

- Common Pronoun Errors (Brigham Young University-Idaho, 2019)

3. Faulty Parallelism

For more on parallelism, see the following resource:

- Parallel Structure (Purdue OWL, n.d.)

4. Dangling and Misplaced Modifiers

For more on dangling modifiers, see the following resource:

- The Dangling Modifier and The Misplaced Modifier (Simmons, 2011)

Key Takeaway

Writing sentences free of common grammar errors such as comma splices and subject-verb disagreement not only helps you avoid confusing the reader and embarrassing yourself but also helps keep your own thinking organized.

Exercises

- Go through the above sections and follow the links to self-check exercises at the end of each section to confirm your mastery of the grammar rules.

- Take any writing assignment you’ve previously submitted for another course, ideally one that you did some time ago, perhaps even in high school. Scan for the sentence and grammar errors covered in this section now that you know what to look for. How often do such errors appear? Correct them following the suggestions given above.

References

Benner, M. L. (2000). Self teaching unit: Subject-verb agreement. Retrieved from https://webapps.towson.edu/ows/moduleSVAGR.htm

Brigham Young University-Idaho Resource Center. (2019). Common Pronoun Errors. Brigham Young University-Idaho. Retrieved from https://content.byui.edu/file/b8b83119-9acc-4a7b-bc84-efacf9043998/1/Grammar-2-5-1.html

Chianello, J. (2014, November 29). Giving youth futures. The Ottawa Citizen. Retrieved from http://ottawacitizen.com/news/local-news/giving-youth-futures

Driscoll, D. L. (2018a, March 28). Parallel structure. Purdue OWL. Retrieved from https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/general_writing/mechanics/parallel_structure.html#:~:text=Parallel%20structure%20means%20using%20the,and%22%20or%20%22or.%22

Goethe, J. W. v. (1809, trans. 1982). Die wahlverwandtschaften, Hamburger ausgabe [Elective affinities, Hamburg edition]. Munich: DTV Verlag. Retrieved from https://en.wikiquote.org/wiki/Johann_Wolfgang_von_Goethe

Paiz, J. M., Berry, C., & Brizee, A. (2018, February 21). Making subjects and verbs agree. Purdue OWL. Retrieved from https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/general_writing/grammar/subject_verb_agreement.html

Plotnick, J. (2003, August 13). Fixing comma splices. University of Toronto. Retrieved from http://www.uc.utoronto.ca/comma-splices