Chapter 11: Group Communication

Adrienne Abel

Chapter Learning Objectives

- Examine the importance of teamwork and how to contribute positively to the team dynamic.

- Define teamwork in professional settings.

- Compare and contrast positive and negative team roles and behaviors in the workplace.

- Discuss group strategies for solving problems.

- Rank several types of response to conflict in the workplace in order of most appropriate to least.

- Explain a collaborative approach to resolving workplace conflict.

- Explain the purpose and contents of the meeting agenda and minutes.

- Demonstrate best practices in web conferencing for professional situations.

- 11.1: Teamwork

- 11.2: Resolving Conflicts

- 11.3: Group and Web-based Meetings

- 11,4: Examples

- 11.5: Practice Makes Perfect

11.1: Teamwork

Section 11.1 Learning Objectives

- Plan and deliver short, organized spoken messages and oral reports tailored to specific audiences and purposes.

- Define teamwork in professional settings.

- Compare and contrast positive and negative team roles and behaviors in the workplace.

- Discuss group strategies for solving problems.

Almost every posting for a job opening in a workplace location lists teamwork among the required skills. Why? Is it because every employer writing a job posting copies other job postings? No, it’s because every employer’s business success depends on people working well in teams to get the job done. A high-functioning, cohesive, and efficient team is essential to workplace productivity anywhere you have three or more people working together. Effective teamwork means working together toward a common goal guided by a common vision, and it’s a mighty force when firing on all cylinders.

- 11.1.1: Team Member Roles

- 11.1.2: Team Problem-Solving

- 11.1.3: Team Leadership

- 11.1.4: Communication within the Team

11.1.1: Team Member Roles

The success of a team falls on the working dynamic of its members. Each team member should put forth an effort to contribute wholeheartedly to the overall team project. The only way to accomplish this task is to assign or defer various roles to each member. If you are serving in the capacity of a project manager, you would focus on creating a diverse team that has various personalities and work ethics. The purpose of creating a diverse team is to embrace the differences that various team members possess. Team diversity doesn’t just relate to ethnicities or gender, but it also means such differences as age, training, technical skills, and work experience. Companies find that projects completed by a diverse team yield favorable results and are more inclusive of many demographics.

In the following video, take note of ways to create an effective team environment:

In Table 11.1.1a, you will find a list of positive group roles and their actions. Table 11.1.1b shows a list of negative group roles. Notice the contrast in the two lists and decide which team would be more suitable for a successful work environment.

Table 11.1.1a: Positive Group Roles

| Role | Actions |

|---|---|

| Initiator-coordinator | Suggests new ideas or new ways of looking at the problem |

| Elaborator | Builds on ideas and provides examples |

| Coordinator | Brings ideas, information, and suggestions together |

| Evaluator-critic | Evaluates ideas and provides constructive criticism |

| Recorder | Records ideas, examples, suggestions, and critiques |

| Comic relief | Uses humor to keep the team happy |

Table 11.1.1b: Negative Group Roles

| Role | Actions |

|---|---|

| Dominator | Dominates discussion so others can’t take their turn |

| Recognition seeker | Seeks attention by relating discussion to their actions |

| Special-interest pleader | Relates discussion to special interests or personal agenda |

| Blocker | Blocks attempts at consensus consistently |

| Slacker | Does little-to-no work, forcing others to pick up the slack |

| Joker or clown | Seeks attention through humor and distracting members |

(Beene & Sheats, 1948; McLean, 2005)

11.1.2: Team Problem-Solving

In any type of environment—within the classroom, in a family setting, or within an employment situation—problems will arise. This will happen within teams just as it will occur between individuals. In Rebecca Knight’s article “Is Your Team Solving Problems, or Just Identifying Them?” the author relates that while team members may ask questions and generate new ideas, constructive feedback should be provided. In order to solve problems effectively, team members can use these steps adapted from Scott McClean (2005):

- Define the problem—Find out what the true problem is and what isn’t.

- Analyze the problem—Figure out the basis of the problem and what’s causing it.

- Establish criteria for a successful resolution to the problem—Set guidelines for how your team would like to gather information regarding the problem (specifics such as timing, placement, parties involved, etc.),

- Consider possible solutions—During this step, all team members should contribute their ideas on how the problem may be resolved.

- Decide on a solution or a select combination of solutions—During this stage, an analysis of all possible solutions should be gathered. The cost and benefits of each proposed solution would be discussed by the entire team.

- Implement the solution(s)—Once a solution has been decided upon, your team will put the plan into action.

- Follow up on the solution(s)—Your team should revisit the situation by either conducting a follow-up meeting or simply sharing the results by interoffice mail, memo, email, etc.

11.1.3: Team Leadership

Successful teams are driven by a good leader. The leader sets the tone for the team, guiding them and helping them to stay on task. If a team leader is not chosen, that leaves a lot of room for error, miscommunication, and misdirection that can ultimately cause the project to be either delayed or not completed. In the following video, a little insight is given into leading teams:

What characteristics make an effective leader? An effective leader possesses a combination of skills, talents, and traits that enables them to direct individuals without cause. Anyone can be groomed in the art of leadership; however, it takes a certain skill set, along with empathy, compassion, and other valuable traits needed to become a leader. The following are some types of leaders that you may come in contact with:

Autocratic leader: This type of leader is self-directed and establishes norms and conduct for the group.

Laissez-faire leader: “Live and let live.” This type of leader allows others to be creative and use their resources. You won’t find someone micromanaging or getting too involved with this type of leadership.

Leader-as-technician: This individual may serve as an expert in some areas that would support the other team members.

Leader-as-conductor: This type of leader guides the team through the movement of the project, setting benchmarks and collaborating frequently with feedback.

Leader-as-coach: Leadership in this form serves as the motivator or cheerleader. Team members can expect specific directions and input in an effort to continue the project moving forward.

Within any work environment, you would desire a fair leader. Unfortunately, there are some leaders who create stressed work environments with their lines of authority. If you experience any of those behaviors, an article from Forbes magazine entitled “13 Effective Tactics for Dealing with a Toxic Boss” gives the following suggestions:

- Seek clarity.

- Do your job and drop your ego.

- Assume positive intent and provide feedback.

- Try to have a candid conversation.

- Start by assessing your own values.

- Learn and adapt.

- Become a trusted partner

- Focus on helping, not judging

- Don’t take it personally

- Control your reactions.

- Set boundaries.

- Avoid them as much as possible.

- Document, document, document.

Another spectrum of a toxic work environment may include harassment—verbal, sexual, or physical. If you experience any of these types of behaviors, please note that action can be taken regarding safeguarding yourself from any undue harm. It is important to follow the guidance given in your employee/company handbook and how to proceed with reporting this behavior. Additionally, you can seek information from the following resources:

- OSHA—Workplace Violence

- Labor Law Information Resources—Louisiana Workforce Commission

- Louisiana Board of Regents—Title IX/Power-Based Violence

11.1.4: Communication within the Team

Communication is vital for completing any project. Discovering ways to effectively communicate with the team should contain inclusive methods for best results. Forbes magazine published an article (Richard, 2020) that discusses strategies for improving communication with team members:

Ensure that your communication has a purpose. If your communication is not clear, your desired message would not be received as intended.

Have a plan when meeting with your team members. You should always prepare a written agenda. Meetings should be brief and kept on task. Additional information regarding agendas will be covered in Section 11.3.1.

Sensitive situations. There may be times when your team will cover sensitive topics. These situations may warrant additional personal conversations to resolve any issues or concerns.

Mode of communication. Make a decision on which mode of communication your team will use throughout the project. Due to differing schedules, your team may choose several avenues such as email, texting, instant messaging, video calls, etc.

Keep your team updated. Throughout your project, the team should receive regular updates. If deadlines for certain items were identified at the beginning of the project, marking them as “completed” states that a goal has been reached.

Your responses to your team and others can help determine if communication is received correctly. This is evidenced in the form of feedback. Feedback may present in several forms: positive or negative. Positive feedback presents as receiving praise for a job well done or giving a satisfactory evaluation of a team member. The opposite type of feedback is negative feedback or negative criticism, where you may receive information about a poorly executed job without any suggestions for improvement. In a leadership role, it is important to always offer suggestions or helpful recommendations in order to assist one’s performance.

Constructive criticism is set apart from negative criticism because it involves improving situations with detailed instructions to execute in an effort to meet expectations. In a leadership role, instead of focusing on the negative aspects, speak to the writer about what is fixable. It is imperative to give clear and specific points that will be needed for the writer to correct their mishaps. Encouraging the writer to take care with revision, spelling, and grammar checking not only will build the confidence of the writer but will also help the writer with future assignments or projects.

Constructive criticism can also be given nonverbally and can be indicated by listening. Becoming a good listener also means being able to take direction or criticism without being defensive. If you immediately begin listing defensive tactics mentally, you’re not effectively listening to the criticism being given.

Receiving constructive criticism in a way that assures the speaker that you understand involves completing the communication process. Indications that you are truly listening revolve around nonverbal clues such as the following:

- Maintaining eye contact shows that you’re paying close attention to the speaker’s words and nonverbal inflections.

- Nodding your head shows that you’re processing and understanding the information coming in, as well as agreeing.

- Taking notes shows that you’re committing to the information by reviewing it later.

The “Poop Sandwich” Method

One way of delivering constructive criticism is to utilize the “poop sandwich” method. With this method, the receiver is made to feel good about themselves to appear more receptive to hearing, processing, and recognizing the constructive criticism being given. If the “poop” (constructive criticism) focuses on the improvement needed, then the receiver will relate it to praise that comes before and/or after (the slices of bread) the improvement has been made. The following table illustrates the “poop sandwich” feedback:

Table 11.1.4.: Poop Sandwich Feedback

| Feedback | Example |

|---|---|

| 1. Sincere, specific praise | Your report really impressed me with its organization and visually appealing presentation of your findings. It’s almost perfect. |

| 2. Constructive criticism | If there’s anything that you can improve before you send it on to the head office, it’s the writing. Use MS Word’s spellchecker and grammar checker, which will catch most of the errors. Perhaps you could also get Marieke to check it out because she’s got an eagle eye for that sort of thing. The cleaner the writing is, the more the execs will see it as a credible piece worth considering. |

| 3. Sincere, specific praise | Otherwise, the report is really great. The abstract is right on point, and the evidence you’ve pulled together makes a really convincing case for investing in blockchain. I totally buy your conclusion that it’ll be the future of financial infrastructure. |

In an earlier chapter, delivering bad news in writing was discussed, but how do you deliver bad news in person? The delivery of bad news in a face-to-face setting is more beneficial because the delivery can be more effective, particularly within the workplace. The majority of people shy away from conflict, thus the preference for using electronic channels to communicate bad news. No one enjoys creating a sad or angry situation that could quickly turn into a retaliatory confrontation or provoke emotional outbursts.

The best plan of action, in this case, would involve having a clear goal. Stephen Covey (1989) recommends beginning with the end in mind. Do you want your negative news to inform or bring about change? If so, what kind of change and to what degree? A clear conceptualization of the goal allows you to anticipate the possible responses, plan ahead, and get your emotional “house” in order.

The response to the news and the audience, regardless of if it involves one person or a group, sets the tone for the interaction itself. It is natural to have feelings of frustration, anger, and hurt; however, displaying these types of feelings can actually worsen the situation further. If the deliverer of the news keeps a mild or neutral tone, then the receiver is more than likely to respond in that same tone.

If you are delivering the bad news to an individual, make sure that the message doesn’t get lost in translation. Find out which mode of communication works best for both parties. Written responses (i.e., email or letter) may work in some instances; however, the tone of the response may be misunderstood. A face-to-face meeting might be the answer, but again, you should watch your body language in your delivery. In either scenario, the deliverer should be comfortable enough to deliver the message.

In the workplace, you may have to deliver bad news to a group of people or a department. A presentation or speech may be the best option for this scenario. Allow for a question-and-answer period and end your delivery on a positive note. You should follow the previous steps mentioned and prepare for a variety of reactions. How you handle yourself in this scenario will provide a basis for how the audience will receive and react to the news.

Key Takeaway

Almost all jobs require advanced teamwork skills, which involve being effective in performing a particular role (e.g., leader) in a working group, contributing to group problem solving, and both giving and receiving constructive criticism.

Exercises

- Think of a group you belong to and identify some of the roles played by its members. Identify your role (give it a label, perhaps based on those given in §10.3.1) and explain how it enriches the group.

- Consider past group work you’ve done in high school or even recently in college and identify a particular problem you had to overcome to guarantee the group’s success. Did the group as a whole contribute to its solution, or did an individual member have to step up and pull through? Describe your problem-solving procedure. Was it successful immediately or did it require fine-tuning along the way?

- Identify a problem that can only be solved with teamwork in the profession you’ll enter into upon graduating. Describe the problem-solving process using the seven-step procedure narrated in §10.3.2.

- Think of a leader you admire and respect, someone who had or has authority over you. How did they become a leader? By appointment, democratic selection, or emergence? How would you characterize their leadership style? Are they autocratic or laissez-faire? Are they like a technician, a conductor, or a coach? Do they use the carrot or the stick to get action from the people they have authority over?

- Roleplay with a classmate the following scenario: You’re a mid-level manager and are concerned about an employee arriving 15–20 minutes late every day, although sometimes it’s around 30–40 minutes. The employee leaves at the same time as everyone else at the end of the day, so that missing work time isn’t made up. What you don’t know (but will find out from talking with the employee) is that they must drop their child off at elementary school shortly before 8 a.m., battle gridlock highway traffic on the way to work (hence the lateness), then leave at a certain time to pick their child up from after-school daycare (hence not being able to stay later). What you do know is that talking with the employee in private is the right way to handle this and that the executive director above you considers it your responsibility to have everyone arriving on time and being paid for their hours as stipulated in their contracts; the director isn’t afraid of firing someone for such a breach of contract, so you have the authority to threaten the employee with that consequence if you feel that it’s necessary. The fact that this employee is being paid for working fewer hours than stipulated in the contract will be a strike against you unless you either get them back on track or fire them if they can’t work their full hours. Be creative in discussing an amicable solution with the employee that satisfies everyone involved. Switch between being both the manager and the employee in your roleplay.

11.2: Resolving Conflicts

Section 11.2 Learning Objectives

- Plan and deliver short, organized spoken messages and oral reports tailored to specific audiences and purposes.

- Rank several types of response to conflict in the workplace in order of most appropriate to least.

- Explain a collaborative approach to resolving workplace conflict.

Behavioral questions are usually asked during a job interview. Potential employers want to know how you would handle a crisis at work if it arises. It is a certainty that conflict will appear at one point in your employment. However, the steps that are taken to resolve the conflict can be practiced so that you can make informed decisions during the crisis situation.

First, we should identify what a conflict is and why it arises. According to McLean (2005), conflict is the physical or psychological struggle associated with the perception of opposing or incompatible goals, desires, demands, wants, or needs. Possessing effective communication skills is key to resolving conflicts, and using positive solutions can affect our daily lives and how we handle issues in the workplace. In the next few sections, we will explore several strategies to resolve conflicts.

11.2.1: The GRIT Method

You might experience conflicts that are serious enough to cause disruption within the workplace culture. This type of disruption can cause low morale, lack of trust, and lackluster productivity. During these times, a method called GRIT can be utilized. GRIT is an acronym for Graduated Reciprocation in Tension-reduction. One side initiates a breakthrough in the form of a compromise regarding one of the demands. The other side responds with a compromise of their own while trying to build trust with one another. Charles E. Osgood (1962) developed this method to assist and ease tensions between the United States and Russia and the threat of using nuclear weapons.

Let’s say you find yourself getting between two conflict parties at your job; on one side is a trusted coworker, Jillian, and on the other is the manager, Dante, whom you like very much. They don’t see eye-to-eye on the way a major aspect of the operation is set up, and it’s caused a rift that is starting to draw other employees in to take sides. Team Jillian doesn’t miss opportunities to take pot-shots at anyone on Team Dante for being management lackeys, and Team Dante has been dismissive of Team Jillian’s concerns, and its members have been threatening to get Team Jillian’s members fired. It doesn’t look like this will end well. Your sympathies go to both sides, so you propose to mediate between them. Applying GRIT in this situation would look like the following:

- Get both sides to agree to talk formally with one another in the meeting room with the goal of resolving the conflict. Reasonable human beings will recognize that the toxic environment is hindering productivity and is bad for business. Team Jillian knows that it will be a hassle having to look for and secure new jobs, and Team Dante knows it’ll likewise be a lot of work to let everyone go and re-hire half the operation, which will take time and will meanwhile slow operations down even further. No one wants this despite everyone taking sides and digging into their chosen positions till now. The willingness to participate in a conflict resolution process requires that both parties show concern for rescuing the relationship.

- After sitting down to talk to one another, actually listen to one another’s concerns. Much conflict in the workplace happens when two sides don’t understand each other’s thinking. Sharing each other’s thoughts in a mature and controlled way will dispel some of the misunderstandings that led to the conflict. One side gets a certain amount of time to state its case uninterrupted. The other gets the same. Then they take turns responding to each other’s points.

- Establish common ground. When two sides are locked in a dispute, they usually share more in common than they realize. After discussing their differences, moving forward toward a resolution must involve establishing points of agreement. If both parties agree that the success of their operation is in their best interests, then you can start with such common goals and then work your way down to more specific points of agreement. These may begin to suggest solutions.

- Discuss innovative solutions to the conflict. With everyone in the room representing their various interests within the organization and listening to one another’s concerns, a truly cooperative collaboration can begin in identifying solutions to operational problems.

- Take turns exchanging concessions GRIT-style. After establishing common ground and considering pathways toward operational solutions, address the lingering differences by getting both sides to prioritize them and offer up the lowest-priority demands as a sacrifice to the deal you want them to strike. If the other side is like this, the principle of reciprocity compels them to drop their lowest-priority demand as well. Then both sides go back and forth like this with each condition until they reach an agreement.

11.2.2: Conflict Resolution Strategies

Conflict arises everywhere communication occurs. Effective communicators can predict, anticipate, and formulate strategies to address conflict in order to successfully resolve it. How you choose to approach conflict influences its resolution. Joseph DeVito (2003) offers us several conflict management strategies that we have adapted and expanded for our use below. Let’s examine these various responses to conflict.

Managing your emotions: Refrain from being perceived as angry or frustrated. Don’t engage in a “war of words.” This can result in hurling insults at another person, which not only can be damaging to the other person but may reflect negatively on you as well.

Empathizing: Put yourself in someone else’s shoes and see if the emotions that they are experiencing feel right. When you complete this step, you are showing emotional intelligence, which is vital to effective communication. Sometimes, just listening to the other’s plight will have a profound effect on you, prompting you to deescalate the situation.

Supportive vs. defensive: In 1961, author Jack Gibb discussed defensive and supportive communication interactions as part of an analysis of conflict management. In the following video, his theories are explained:

Face-saving vs. face-detracting: A face-detracting strategy compromises the respect, integrity, or credibility of the targeted person. On the other hand, face-saving strategies protect credibility and separate the message from the messenger.

Backpacking: This involves imaginary luggage in which we carry unresolved grievances and grudges over time.

Avoiding: This trait is considered as either a healthy or unhealthy response to conflict, depending on the seriousness of the situation.

Escalating: This trait is considered as either an appropriate or inappropriate response depending on the issue’s importance. Examples would include overreacting to a trivial issue, using a loud voice while using offensive language, becoming violent regarding an issue, etc.

Key Takeaway

Conflict is inevitable in any workplace with human interaction, so responding to it in ways that promote professionalism requires excellent communication skills and conflict resolution strategies.

Exercises

- Write a description of a situation you recall where you came into conflict with someone else. It may be something that happened years ago or a current issue that just arose. Using the principles and strategies in this section, describe how the conflict was resolved or could have been resolved.

- Can you think of a time when a conflict led to a new opportunity, better understanding, or other positive result? If not, think of a past conflict and imagine a positive outcome. Write a two- to three-paragraph description of what happened or what you imagine could happen.

11.3: Group and Web-based Meetings

Section 11.3 Learning Objectives

- Explain the purpose and contents of the meeting agenda and minutes.

- Demonstrate best practices in web conferencing for professional situations.

Although they can be boring, pointless, and futile exercises if poorly organized, professional group meetings are opportunities to exchange information and produce results when used appropriately in any business or organization. A combination of thoughtful preparation and cooperative execution makes all the difference. Though they typically take place in boardrooms, where participants meet in person, web conferencing enables face-to-face meetings anywhere in the world. In this section, we examine what makes for effective in-person and virtual meetings before, during, and after.

- 11.3.1: Developing the Agenda

- 11.3.2: How to Conduct a Meeting

- 11.3.3: The Importance of Meeting Minutes

11.3.1: Developing the Agenda

Every meeting needs a clear purpose, such as an agenda. An agenda is a document that lists all issues for the business that will be discussed at the meeting. The formality of the meeting will determine which format is used to prepare the agenda. For an informal meeting, the agenda will only list the items that will be discussed during that particular meeting. For a more formal meeting, the agenda could list items such as times, events, speakers, meeting location, and other pertinent information.

The following items are a standard agenda outline:

- The time, date, location, list of participants, purpose statement, call to order identifying the person chairing or leading the meeting

- Introductions if there is even one new participant in the group

- Roll call listing the participants expected, which can be silently checked off by the participant in charge of recording minutes; a note is made beside the name of any absentees so that a list of actual participants is ready for the minutes

- Approval of the minutes, where corrections to the previous meeting’s minutes (sent out soon after the previous meeting) are suggested by participants who were there before the minutes are approved by the group for official archiving

- Old business for discussing any issues left unresolved (“tabled”) in the previous meeting

- New business listing topics for discussion in the order of priority so that the most important issues can be dealt with first so that items of lesser importance don’t push the important ones off the agenda and into the next meeting if the lesser items end up taking longer than expected

- The expected length of time is indicated for each item, with contentious items getting extra time to accommodate the depth of discussion expected.

- Items may include proposals for new initiatives, brief presentations reporting on recent developments or existing initiatives, and discussions about recent or upcoming developments

- Any preparatory work is indicated such as readings (e.g., reports that will be discussed) or reports that must be presented by individuals.

- Adjournment for discussing when the next meeting shall take place.

Those individuals who will participate regarding specific agenda items for the meeting should be contacted well in advance of the proposed meeting date. Once those individuals have been confirmed (preferably in writing or via email), the agenda should be prepared. It is also imperative that the meeting room and proposed time period are confirmed. After these specifics are secured, the meeting agenda should be sent to all meeting participants at least a week prior to the scheduled meeting date.

The use of certain software products allows for the ease of sending meeting invitations. The invitations can be confirmed through this medium as well as track those individuals who have “accepted” or “declined” attending the meeting. If you are the organizer of this meeting, you also have the option of sending meeting reminders one day prior to the meeting.

It is key to assure that your meeting runs smoothly. One way to accomplish this would be to ensure that you have adequate space for the meeting participants. You may want to “preset” the meeting by setting out pens, notepads, coffee/tea/water, and/or snacks. Also prior to the meeting, make sure that any electronic devices that may be needed for the meeting, such as a laptop or a projector, are in working order.

11.3.2: How to Conduct a Meeting

In this video, you can learn a few tips on conducting meetings:

Exploring this concept further, Mary Ellen Guffey (2007) provides a useful checklist for participants as a guide for how to conduct oneself during a meeting, adapted below for our use:

- Be prepared and have everything you need on hand.

- Arrive on time and stay until the meeting adjourns (unless there are prior arrangements).

- Turn off cell phones and personal digital assistants; don’t just switch them to vibrate and put them on the tabletop.

- Engage in polite small talk with participants before the meeting begins; don’t cut yourself off from human interaction by looking at your phone.

- Follow the established protocol for taking turns speaking.

- Respect time limits.

- Leave the meeting only for established breaks or emergencies.

- Demonstrate professionalism in your verbal and nonverbal interactions.

- Communicate interest and stay engaged in the discussion.

- Avoid tangents and side discussions.

- Respect space and don’t place your notebook or papers all around you.

- Clean up after yourself.

- Engage in conversation with other participants after the meeting.

11.3.3: The Importance of Meeting Minutes

Each meeting should be documented. Meeting minutes serve as the historical document for the meeting. It is imperative to record the entire meeting, thus you will need to have adequate equipment and materials to accomplish this. For best accuracy, the use of a recorder during the meeting would be beneficial. By using the recorder, pertinent details won’t be left out. When interpreting the notes, you should not include your personal thoughts or ideas. You must remain neutral, particularly in relation to a topic of disagreement.

Although you may use a recording device, you will still need to listen carefully and take notes. Completing this step will assist you in combining the information that you had written with the information that you hear on the recording. Writing a draft of the minutes allows you to check for spelling and grammar errors and to read it aloud. Make any necessary corrections and then prepare your final draft. Once the required signatures (if needed) have been obtained, the minutes are ready for dissemination.

As technology evolves constantly, various meeting tools become available. Popular meeting tools include Zoom, Microsoft Teams, and Google Meet.

11.4: Examples of Meeting Minutes

- 11:41: Team Dynamics Video

- 11.4.2: Information regarding Team Contracts/Expectancies

- 11.4.3: Sample of an Agenda

- 11.4.4: Sample of Meeting Minutes

11.4.1: Team Dynamics Video

11.4.2: Information regarding Team Contracts/Expectancies

An example of a group contract.

11.4.3: Sample of an Agenda

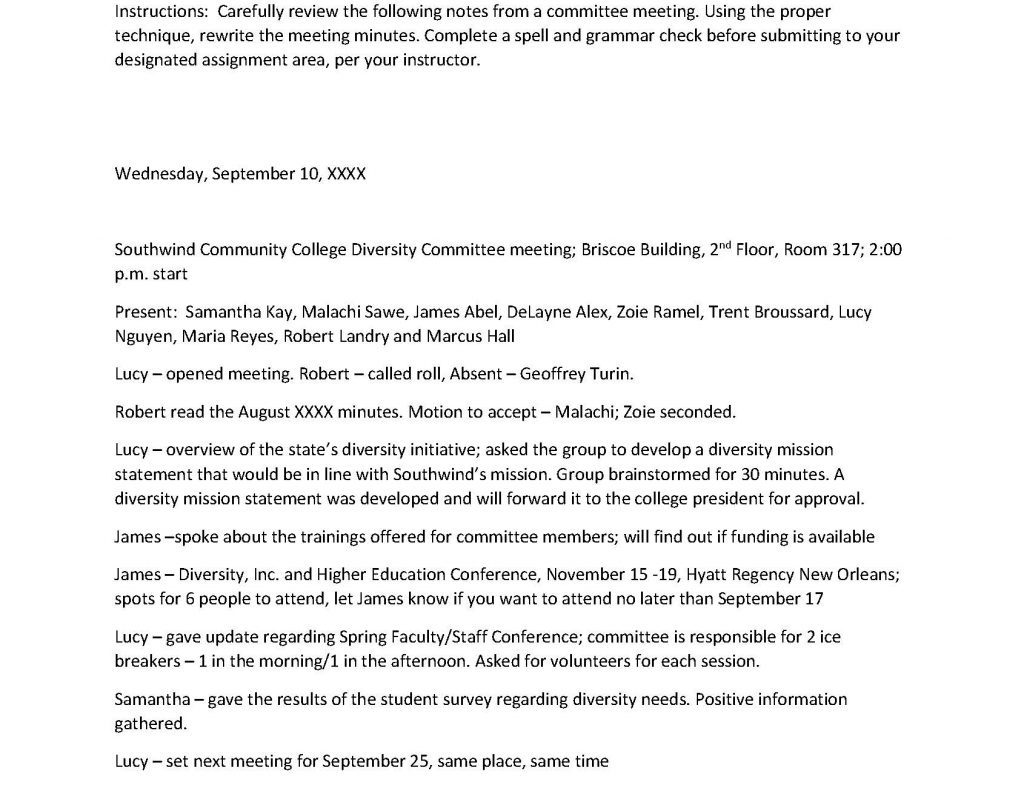

11.4.4: Sample of Meeting Minutes

11.5: Practice Makes Perfect!

- 11.5.1: Questions regarding Team Contract (What-If Scenarios)

- 11.5.2: Agenda Exercise: Rewrite/Revise

- 11.5.3: Rewrite/Revise Meeting Minutes

- 11.5.4: Agenda Knowledge Quiz

11.5.1: Questions regarding Team Contract (What-If Scenarios)

11.5.2: Agenda Exercise: Rewrite/Revise

11.5.2: Agenda Exercise: Rewrite/Revise

11.5.3: Rewrite/Revise Meeting Minutes

11.5.4: Agenda Knowledge Quiz

Test Your Understanding: Agenda Knowledge

References

BBC News. (2017, March 10). Children interrupt BBC News interview—BBC News [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Mh4f9AYRCZY

GreggU. (2020, December 14). Team dynamics [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/hvsi5OHeHMI

Guffey, M. (2007). Essentials of business communication (7th ed.). Mason, OH: Thomson/Wadsworth.

Kennedy, B. (1997). Robert’s Rules of Order: Quick reference and tools for meetings. Retrieved from https://robertsrules.org/

Lovgren, B. (2017, January 5). The biggest do’s and don’ts of video conferencing. Entrepreneur. Retrieved from https://www.entrepreneur.com/article/238902

Muir, T. (2022). Trevor Muir— Group Contract. Trevor Muir. Retrieved June 8, 3033, from https://www.trevormuir.com/blog/group-contract

Usborne, S. (2017, December 20). The expert whose children gatecrashed his TV interview: “I thought I’d blown it in front of the whole world.” The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/media/2017/dec/20/robert-kelly-south-korea-bbc-kids-gatecrash-viral-storm