Chapter 15: Ethics

Sydney Epps

Chapter Learning Objectives

- Define professional behavior according to employer, customer, coworker, and other stakeholder expectations.

- Explain the importance of ethics as part of the persuasion process.

- Define and provide examples of sexual harassment in the workplace, as well as strategies for how to eliminate it.

- Identify and provide examples of eight common fallacies in persuasive speaking.

- Plan and deliver short, organized spoken messages and oral reports tailored to specific audiences and purposes.

From the moment we started considering what communication skills employers desire onward throughout this guide, we’ve been examining aspects of professional behavior. A recurring theme has been the importance of being nice. The logic is that if you’re nice and the people you work with and for like you because they feel that they can trust you and are productive when you collaborate with them, you’ll keep your job and be presented with attractive new opportunities. In this section, we’ll look closer at behaviors that will get you liked and open doors for you.

Professionalism, Etiquette, and Ethical Behavior Topics

- 15.1: Professional Behavior in the Workplace

- 15.2: Business Etiquette

- 15.3: Respectful Workplaces in the #MeToo Era

- 15.4: Speaking Ethically and Avoiding Fallacies

15.1: Professional Behavior in the Workplace

We’ve said from the beginning that professional communication must always cater to the audience. This is true, especially in face-to-face interactions where, unlike with written communication, you can assess audience reaction in real-time and adjust your message accordingly. This places the responsibility of behaving professionally in the workplace solely on you. When we speak of professional behavior, we mean the following aspects that generally fall under the banner of soft skills:

- Civility

- Social intelligence

- Emotional intelligence

- Social graces

We’ll consider these aspects in more detail throughout this subsection, but first, we’ll spend some time on the personality traits of successful professionals.

We must be careful with how we define success when we speak of personality, however. Those who lack the soft skills associated with the above aspects are difficult to work with and are usually demoted or fired. In rare instances, cruel, selfish, arrogant, narcissistic, or sociopathic people rise to positions of power through a combination of enablers tolerating or even rewarding their anti-social behavior and their own lying, cheating, and bullying. This is an unfortunate reality that’s difficult to watch, but it’s important that the rest of us avoid being enablers. It’s also important that we don’t let their bad example lead us into thinking that such behavior is right. It isn’t, and the proof is the suffering it spreads among people in their sphere of influence. For every horrible person who moves up the corporate ladder, there’ll be a trail of broken, bitter, and vengeful people in their wake. The loathing most people feel toward such people proves the importance of conducting ourselves otherwise.

- 15.1.1: The Five Qualities of a Successful Professional

- 15.1.2: Civility

- 15.1.3: Social Intelligence

- 15.1.4: Emotional Intelligence

- 15.1.5: Social Graces

15.1.1: The Five Qualities of a Successful Professional

A persistent idea within the field of psychology is that there are five basic personality traits, often known as the “Big Five” or by the acronyms OCEAN or CANOE. Each trait contains within it a sliding scale that describes how we behave in certain situations. The five are as follows:

- Openness to experience: curious and innovative vs. cautious and consistent

- Conscientiousness: goal-driven and detail-oriented vs. casual and careless

- Extraversion: outgoing and enthusiastic vs. solitary and guarded

- Agreeableness: cooperative and flexible vs. defiant and stubborn

- Neuroticism: anxious and volatile vs. confident and stable

Except for neuroticism, most of the traits as named correlate with professional success. Researchers have found that successful people are generally organized, innovative, outgoing, cooperative, and stable, although extraverts don’t do as well as introverts on individual tasks, and agreeableness doesn’t necessarily lead to a high salary (Spurk & Abele, 2010; Neal et al., 2011).

Blending these with Guffey, Loewy, and Almonte’s six dimensions of professional behavior in Essentials of Business Communication (2016) and putting our own spin on these ideas, Table 15.1.1 below presents a guide for how generally to be successful in your job, how to be well liked, and how to be happy. Consider it also a checklist for how to be a decent human being.

Table 15.1.1: The Five Qualities of a Successful Professional

| Quality | Specific Behaviors |

|---|---|

| Conscientious | Consistently do your best work in the time you have to do it Be organized and efficient in your workflow and time management Be realistic about what you can accomplish and follow through on commitments Go the extra mile for anyone expecting quality work from you (while respecting time, budget, or other constraints) Finish your work on time rather than leave loose ends for others |

| Courteous | Speak and write clearly at a language level your audience understands Be punctual: arrive at the workplace on time and deliver work by the deadline Notify those expecting you when you’re running late Apologize for your own errors and misunderstandings Practice active listening Share your expertise with others and be a positive, encouraging mentor to those entering the workplace |

| Tactful | Exercise self-control with regard to conversational topics and jokes Avoid contentious public and office politics, especially in writing Control your biases by being vigilant in your diction (e.g., word choices involving gendered pronouns) Accept constructive criticism gracefully Provide helpful, improvement-focused feedback mixed with praise Keep negative opinions of people to yourself Be patient, understanding, and helpful toward struggling colleagues |

| Ethical | Avoid even small white lies and truth-stretching logical fallacies Avoid conflicts of interest or even the perception of them Pay for products and services as soon as possible if not right away Respect the confidentiality of private information and decisions Focus on what you and your company do well rather than criticize competitors to customers and others Follow proper grievance procedures rather than take vengeance Be charitable whenever possible |

| Presentable | Be positive and friendly, especially in introductions, as well as generous with your smile Present yourself according to expectations in grooming and attire Practice proper hygiene (showering, dental care, deodorant, etc.) Follow general rules of dining etiquette |

Source: Guffey, Loewy, & Almonte (2016, p. 309: Figure 10.1)

15.1.2: Civility

Civility simply means behaving respectfully toward everyone you interact with. Being civilized means following the golden rule: treat others as you expect to be treated yourself. The opposite of civility is being rude and aggressive, which creates conflict and negatively affects productivity in the workplace because it creates a so-called chilly climate or a toxic work environment. Such a workplace makes people uncomfortable, miserable, or angry—not emotions normally conducive to people doing their best work.

15.1.3: Social Intelligence

In the decades you’ve been immersed in the various cultures you’ve passed through, you’ve come to understand the (often unspoken) rules of decent social interaction. Having social intelligence means following those rules to cooperate and get along with others, especially in conversation. This includes reading nonverbal cues so that you know:

- How and when to initiate conversation

- When it’s your turn to speak and when to listen in order to keep a conversation going

- What to say and what not to say

- How to say what you mean in a manner that will be understood by your audience

- When and how to use humor effectively and when not to

- How and when to end conversation gracefully

People who lack social intelligence, perhaps because they missed opportunities to develop conversational skills in their formative school years, come off as awkward in face-to-face conversation. They typically fail to interpret correctly nonverbal cues that say “Now it’s your turn to speak” or “Okay, I’m done with this conversation; let’s wrap it up.” It’s difficult to interact with such people because either they make you do all the work keeping the conversation going or they don’t let you speak and keep going long after you wanted it to stop, forcing you to be slightly rude in ending it abruptly. Like any other type of intelligence, however, social intelligence can be developed through an understanding of the principles of good conversation and practice.

15.1.4: Emotional Intelligence

Like social intelligence, emotional intelligence (EI) involves being a good reader of people in social contexts, being able to distinguish different emotions, and knowing what to do about them with regard to others and yourself. Strong EI means knowing how a person is likely to react to what you’re about to say and adjusting your message accordingly and then adjusting again according to how they actually react. Though we often hide our inner emotional state—smiling and looking happy when we’re feeling down or wearing a neutral “poker face” to mask our excitement—in professional situations, EI enables us to get a sense of what others are actually feeling despite how they appear. It involves reading subtle nonverbal signals such as eye movements, facial expressions and fleeting micro-expressions (Ekman, 2017), posture, hands, and body movements for how they betray inner feelings different from the outward show. Beyond merely reading people, however, EI also requires knowing how to act, such as empathizing when someone is upset—even if they’re trying to hide it and show strength—because you recognize that you would be upset yourself if you were in their position.

Every interaction you have is colored by emotion—both yours and the person or people you interact with. Though most routine interactions in the workplace are on the neutral-to-positive end of the emotional spectrum, some dip into the red—anywhere from slightly upset and a little sad to downright furious or suicidal. Whether you keep those emotions below the surface or let them erupt like a volcano depends on your self-control and the situation. Expressing such emotions in the workplace requires good judgment, represented by the 3 Ts:

- Tact: Recognizing that what you say has a meaningful impact, tact involves the careful choice of words to achieve intended effects. In a sensitive situation where your audience is likely to be upset, for instance, tact requires that you use calming and positive words to reduce your message’s harmful impact (see Chapter 8 on negative messages). When you’re upset, tact likewise involves self-restraint so that you don’t unleash the full fury of what you’re feeling if it would be inappropriate. When emotions are running high, it’s important to recognize that they are just thoughts that come and go. You may need some additional time to process information when you’re in a different emotional state before communicating about it.

- Timing: There’s a time and place for expressing your emotions. Expressing your anger when you’re at the height of your fury might be a bad move if it moves you to say things you’ll later regret. Waiting to cool down so that you can tactfully express your disappointment will get the best results if it’s an important matter. If it’s a trivial matter, however, waiting to realize that it’s not worth the effort can save you the trouble of dealing with the fallout of a strong and regrettable reaction.

- Trust: You must trust that the person you share your feelings with will respect your privacy and keep whatever you say confidential or at least not use it against you.

By considering these 3 Ts, you can better manage the expression of your own emotions and those of the people you work with and for in the workplace (Business Communication for Success, 2015, 14.6).

Like those who lack social intelligence, those who lack emotional intelligence can often be difficult to work with and offensive, often without meaning to be. When someone fails to understand the emotional “vibe” of their audience (fails to “read the room”), we say that they are “tone deaf.” This can be a sign of immaturity because it takes years to develop EI through extensive socialization in your school years and beyond, including learning how and why people take offense to what you say. Someone who jokes openly about another’s appearance in front of them and an audience, for instance, either fails to understand the hurt feelings of the person who is the butt of the joke or doesn’t care. Either way, people like this are a liability in the workplace because their offense establishes an environment dominated by insecurity—where employees are afraid that they’ll be picked on as if this were the elementary school playground. They won’t do their best work in such a “chilly climate” or toxic environment.

15.1.5: Social Graces

Social graces include all the subtle behavioral niceties that make you likable. They include manners such as being polite, etiquette (e.g., dining etiquette), and your style of dress and accessories. We will explore most of these in the following section. For now, we can list some of the behaviors associated with social graces:

- Pronouncing someone’s name correctly

- Saying please when asking someone to do something

- Saying thank you when given something you accept

- Saying no, thank you, but thanks for the offer when offered something you refuse

- Complimenting someone for something they’ve done well

- Speaking positively about others and refraining from negative comments

- Smiling often

- Being a good listener

Of course, there is much more to social graces, but let’s focus now on specific situations in which social graces are expressed.

15.2: Business Etiquette

Etiquette is a code of behavior that extends to many aspects of how we present ourselves in social situations. We’ve examined this throughout this guide in specific written applications (e.g., using a well-mannered, courteous style of writing, such as saying please when asking someone to do something). Though we’ll examine specific applications of etiquette associated with various channels (e.g., telephone) throughout this chapter, we will here focus on dining etiquette and dress.

15.2.1: Dining Etiquette

If you are invited out for a lunch by a manager, it’s probably not just a lunch. They will assess how refined you are in your manners so that they know whether they can put you in front of clients doing the same and not embarrass the company. Though it may not be obvious, they’ll observe whether you use your utensils correctly, chew with your mouth closed, wait till your mouth is empty before speaking or cover your mouth with your hand if you must speak while chewing, and how you position your cutlery when you’re done. Why does any of this matter?

Though all of this seems like it has nothing to do with the quality of work, it shows the extent to which you have developed fastidious habits and self-awareness. Someone who chews with their mouth open, for instance, either lacks the self-awareness to know that people tend to be disgusted by the sight of food being chewed or doesn’t care what people think. Either way, that lack of self-awareness can lead to behaviors that will ruin their reputation, as well as that of the company they represent. The University of Kansas presents a handy Dining Etiquette (Kent State University, n.d.) for starters.

15.2.2: Dressing Appropriately for the Workplace

When we hear the word uniform, we often think of a very specific style, such as what a police officer or nurse wears. In a general sense, however, we all wear uniforms of various styles in whatever professional or institutional environment we participate in. Dressing appropriately in those situations and in the workplace specifically has everything to do with meeting expectations. In an office environment, clients, coworkers, and managers expect to see employees in either suits or a business-casual style of dress depending on the workplace. In such situations, conformity is the order of the day, and breaking the dress code can be a serious infraction. Guidelines on Dress Code (The Washington Center, 2021)

Though some infractions are becoming less serious in many places because the general culture is becoming more accepting of tattoos, piercings, and dyed hair as more and more people use these to express themselves, you might need to be careful. Consider the following points:

- Tattoos: Though a significant proportion of the population has tattoos and therefore they are more acceptable across the board, overly conspicuous tattoos are still considered taboo. Tattoos on the face, neck, or hands, for instance, are considered risky because of their association with prison and gang branding. Tattoos that can be covered by a long-sleeved shirt with a collar and slacks are a safe bet. However, if you have tattoos on your forearms depicting scenes of explicit sex or violence, consider either getting them removed or never rolling up your sleeves if you want to get hired and keep your job.

Army Staff Sgt. Michael Romero shows his tattoos (U.S. Army photo by Sgt. Adrian Borunda/Released, 2015, Public Domain Mark 1.0) - Piercings: Of course, earrings are de rigueur for women and acceptable for men as well. However, earlobe stretching and piercings on the nasal septum or lips are still generally frowned upon in professional settings. Any serious body modification along these lines is acceptable in certain subcultures, but not in most workplaces.

- Dyed hair: As with tattoos and piercings, hair dye is becoming more acceptable generally, but extreme expression is inadvisable in any traditional workplace. Where customer expectations are rigid (e.g., in a medical office), seeing someone with bright pink hair will give the impression of an amateur operation rather than a legitimate health care facility.

Because conformity is the determining factor of acceptability in proper attire in any particular workplace, the best guide for how to dress when you aren’t given a specific uniform is what everyone else wears. Observe closely their style and build a wardrobe along those lines. If the fashion is slacks with a belt that matches the color of your shoes and a long-sleeve, button-up, collared shirt for men and a full-length skirt and blouse for women, do the same (Feloni, Lee, & Cain, 2018). Nevertheless, professionals in a number of fields have spoken up about the way in which professionalism can follow colonialist norms that marginalize people of non-European descent; for instance, a front tooth gap (considered a symbol of beauty or good luck in some cultures), tightly-coiled hair (or “afros,” braids, and locs), hijabs (hair coverings often worn by women who practice Islam), or a bindi (a body adornment which uses a red dot between the eyebrows on the forehead worn by Hindu and Jain women) may illicit illegal discrimination within workplaces and are ways global diversity may not align with traditional norms (Frye et al., 2020). It is the duty of workplaces to acknowledge their appreciation for these distinct geographical, communal, and religious differences by educating staff on cultural competency, the skills associated with inclusion and personalized interaction (Vescio, Gervais, Heiphetz, & Bloodhart, 2014).

15.3: Respectful Workplaces in the #MeToo Era

- 15.3.1: The Prevalence of Sexual Harassment in the Workplace

- 15.3.2: What is Sexual Harassment?

- 15.3.3: LGBT Harassment

- 15.3.4: How to Make the Workplace More Respectful

Most of this chapter and guide focuses on how we should behave to be effective, respected professionals in our respective workplaces. Unfortunately, this isn’t what we always see in actual workplaces. Misbehavior is rampant and is especially harmful when it’s harassment of a sexual nature. The broader culture took a hopeful step forward toward more respectful workplaces in 2017–2018 with the rise of the #MeToo and Time’s Up movements.

The founder of the #MeToo movement—Tarana Burke—brought forth the understanding of a need for conversation surrounding sexual assault against women and children as a survivor of childhood sexual violence. Though initially a response to high-profile sexual assault cases in the entertainment industry where perpetrators often went unpunished for decades, #MeToo activists successfully brought the movement to the broader culture via social media. Encouraged by a series of public accusations, firings, and resignations of prominent men in the entertainment, media, and political arenas throughout North America, women everywhere were encouraged to challenge the widespread toleration of common sexual harassment and assault by reporting incidents to their employers and speaking out to shame everyday offenders in social media. For those who were unaware, it revealed the troubling extent of sexual harassment in workplaces.

15.3.1: The Prevalence of Sexual Harassment in the Workplace

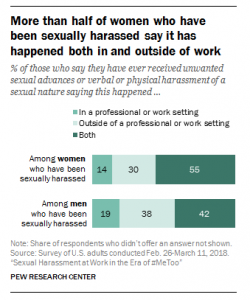

According to the Pew Research Center (Graf, 2018), “half of Americans think that men getting away with this type of behavior is a major problem” (para. 7). Forty percent of women (and 16% of men) say they’ve experienced sexual harassment at work; this number has remained stagnant since the 1980s. In a separate online survey of 2000 Canadians nationwide, 34% of women reported experiencing sexual harassment in the workplace and 12% of men, and nearly 40% of those say it involved someone who had a direct influence over their career success (Navigator, 2018, p. 5). These perceptions are completely out of step with what top executives believe, with 95% of 153 surveyed Canadian CEOs and CFOs confirming that sexual harassment is not a problem in their workplaces (Gandalf Group, 2017, p. 9). Clearly there are differences of opinion between those who experience sexual harassment on the floor and those in the executive suites who are responsible for the safety of their employees, and much of the confusion may have to do with how sexual harassment is defined.

15.3.2: What Is Sexual Harassment?

The US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission’s definition of sexual harassment is quite broad but oriented more toward the perception of the person offended than the intentions of the offender. Though there is nothing wrong with discrete flirtation between two consenting adults on break at work, a line is crossed as soon as one of them—or third-party observers—feels uncomfortable with actions or talk of a sexual nature. Sexual harassment is a form of sex discrimination that violates Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

It is unlawful to harass a person (an applicant or employee) because of that person’s sex. Harassment can include “sexual harassment” or unwelcome sexual advances, requests for sexual favors, and other verbal or physical harassment of a sexual nature.

Harassment does not have to be of a sexual nature, however, and can include offensive remarks about a person’s sex or gender. For example, it is illegal to harass a woman by making offensive comments about women in general.

Both the victim and the harasser can be either a woman or a man, and the victim and harasser can be the same sex and/or gender.

Unwelcome sexual advances, requests for sexual favors, and other verbal or physical conduct of a sexual nature constitute sexual harassment when submission to or rejection of this conduct explicitly or implicitly affects an individual’s employment; unreasonably interferes with an individual’s work performance; or creates an intimidating, hostile, or offensive work environment.

Sexual harassment can occur in a variety of circumstances, including but not limited to the following:

- The victim as well as the harasser may be a woman or a man. The victim does not have to be of the opposite sex.

- The harasser can be the victim’s supervisor, an agent of the employer, a supervisor in another area, a coworker, or a non-employee.

- The victim does not have to be the person harassed but could be anyone affected by the offensive conduct.

- Unlawful sexual harassment may occur without economic injury to or discharge of the victim.

- The harasser’s conduct must be unwelcome (“Facts about Sexual Harassment,” 2002).

15.3.3: LGBT Harassment

Test Your Understanding

Though data on harassment experienced by transgender and lesbian, gay, or bisexual (LGB) employees is emerging, the few studies done conclude that harassment toward this demographic includes “sexually-based behaviors (such as unwanted sexual touching or demands for sexual favors) as well as gender- [or orientation-] based harassment” (Feldblum & Lipnic, 2016).

The Williams Institute (2011) notes that 35% of LGBT-identified workers experienced direct harassment in their profession; within the Human Rights Campaign’s Degrees of Equality Report: A National Study Examining Workplace Climate for LGBT Employees (2009), 58% of LGBT respondents said they heard derogatory comments or verbiage regarding LGBT people in the workplace. The Williams Institute (2011) also found that transgender individuals generally experience higher rates of harassment than cisgender LGB people.

In a large-scale survey by the National Center for Transgender Equality and National Gay and Lesbian Task Force (2011), half of those surveyed reported workplace harassment; 41% received intrusive inquiries in regard to their gender identity (including their bodies and medical information), and 45% have been referred to by pronouns that did not align with their identity “repeatedly and on purpose” while on the job (Feldblum & Lipnic, 2016). Sixty-three percent (63%) experienced an extreme act of discrimination, those that impact a person’s quality of life and ability to sustain themselves financially or emotionally:

- Lost job due to bias

- Eviction due to bias

- School bullying/harassment so severe the respondent had to drop out

- Teacher bullying

- Physical assault due to bias

- Sexual assault due to bias

- Homelessness because of gender identity/expression

- Lost relationship with partner or children due to gender identity/expression

- Denial of medical service due to bias

- Incarceration due to gender identity/expression

In Bostock v. Clayton County, Georgia, No. 17-1618 (S. Ct. June 15, 2020), the Supreme Court held that firing individuals because of their sexual orientation or transgender status violates Title VII’s prohibition on discrimination because of sex. The Court reached its holding by focusing on the plain text of Title VII. The law forbids sexual orientation and gender identity discrimination when it comes to any aspect of employment, including hiring, firing, pay, job assignments, promotions, layoff, training, fringe benefits, and any other term or condition of employment (“Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity (SOGI) Discrimination”).

15.3.4: How to Make the Workplace More Respectful

Though the US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission places the responsibility of ensuring a harassment-free workplace squarely on the employer, all employees must do their part to uphold one another’s right to work free of harassment. Of course, experiencing harassment places the victim in a difficult position with regard to their job security, as does witnessing it and the duty to report it. The situation is even more complicated if the perpetrator has the power to promote, demote, or terminate the victim’s or witness’s employment. If you find yourself in such a situation, seeking the confidential advice of an ombudsperson or person in a similar counseling role should be your first recourse. Absent these internal protections, consider seeking legal counsel.

If you witness sexual or other types of harassment, what should you do? The following guide may help:

- If you can play any additional role in stopping the harassment before it continues, try to get the attention of the person being harassed and ask them if they want support and what you can do to assist. If it’s welcome from the victim and safe for both you and them, try to place yourself between them and the attacker. If the victim is handling the attack in their own way, respect their choice.

- If it’s safe for you to do so, try recording video of the incident on your smartphone. The mere presence of the phone may act as a deterrent to further harassment. If not, however, a record of the incident will be valuable in the post-incident pursuit of justice.

- If the harassment continues, try to de-escalate the situation non-violently by explaining to the offender that the one being harassed has a right to work in peace. Only resort to violence if it’s defensive.

- After a safe resolution, follow up with the person being harassed about what you can do for them (American Friends Service Committee, 2016). Reporting the attack to appropriate authorities, assuring any evidence gained is transmitted to the victim, and serving as a witness to the attack are all helpful ways to use your presence.

Of course, every harassment situation is different and requires quick-thinking action that maintains the safety of all involved. The important thing, however, is to act as an ally to the person being harassed. The biggest takeaway from the development of the #MeToo and Time’s Up movements is that a workplace culture that permits sexual harassment will only end if we all do our part to ensure that offenses no longer go unreported and unpunished.

15.4: Speaking Ethically and Avoiding Fallacies

When we discussed persuasive messages earlier, we focused on best practices without veering much into what’s considered offside in the art of persuasion. When we consider ethical behavior in the workplace, it’s worth revisiting the topic of persuasion so that we can address how not to persuade. In other words, how can we avoid manipulating someone in professional situations so that they don’t later feel like they were taken advantage of?

In the context of communication, manipulation is the management of facts, ideas, or points of view to play upon people’s insecurities or to use emotional appeals to one’s own advantage. Though emotional appeals were part of the rhetorical triangle discussed earlier, they cross the line into manipulation when motivated by an attempt to do something against the best interests of the audience, which expects that you treat them with respect. Deliberately manipulating them by inciting fear or guilt is unethical. Likewise, deception is unethical because it uses lies, partial truths, or the omission of relevant information to deceive. No one likes to be lied to or led to believe something that isn’t true. Deception can involve intentional bias or the selection of information to support your position while negatively framing any information that might challenge your audience’s belief.

Other unethical behaviors with respect to an audience such as a workplace team include coercion and bribery. Coercion is the use of power to make someone do something they would not choose to do freely. It usually involves threats of punishment, which get results at least while the “stick” is present but results in hatred toward the coercing person or group and hence a toxic work environment. Bribery, which is offering something in return for an expected favor, is similarly unethical because it sidesteps normal, fair protocol for personal gain at the audience’s expense. When the rest of the team finds out that they lost out on opportunities because someone received favors for favors, an atmosphere of mistrust and animosity—hallmarks of a toxic work environment—hangs over the workplace.

15.4.1: Eleven Unethical Persuasive Techniques

Though you may be tempted to do anything to achieve the result of convincing someone to act in a way that benefits you and your company or organization, certain techniques are inherently unethical. The danger in using them is that they will be seen for what they are—dishonest manipulation—and you’ll lose all credibility rather than achieve your goal. Just as we have a set of DOs for how to convince someone effectively in a decent way, we also have a set of DON’Ts for what not to do.

In Ethics in Human Communication, Richard Johannesen (1996) offers eleven points to consider when speaking persuasively. Do not:

- Use false, fabricated, misrepresented, distorted, or irrelevant evidence to support arguments or claims

- Intentionally use unsupported, misleading, or illogical reasoning

- Represent yourself as an “expert” (or even informed) on a subject when you’re not, as in the case of “mansplaining” (McClintock, 2016)

- Use irrelevant appeals to divert attention from the issue at hand

- Ask your audience to link your idea or proposal to emotion-driven values, motives, or goals to which it is unrelated

- Deceive your audience by concealing your real purpose, your self-interest, the group you represent, or your position as an advocate of a viewpoint

- Distort, hide, or misrepresent the number, scope, intensity, or undesirable features of consequences or effects

- Use “emotional appeals” that lack a supporting basis of evidence or reasoning

- Oversimplify complex, multi-layered, nuanced situations into simplistic, two-valued, either/or, polar views or choices

- Pretend certainty where tentativeness and degrees of probability would be more accurate

- Advocate for something that you yourself do not believe in

If you tried any of the above tricks and were found out by a critical-thinking audience, you risk irreparable damage to your reputation personally and that of your company.

Though you might think that the above guidelines wipe out most of a marketer’s available techniques, in fact, they leave plenty of room for creative argument following the model for persuasive argument outlined above. After all, the goal of any such argument in a professional situation is to achieve a mutually beneficial result, one where both you and your audience benefit by getting something you both want or need in a free and honest exchange. Your audience will appreciate your fair dealing as you build your credibility.

15.4.2: Avoiding Fallacies

Logicians (experts on logic) have long pointed out a set of rhetorical tricks, called fallacies, that charlatans use to convince others of an argument that has no merit on its own. Though these fallacies are typically deceptive in nature, they still manage to convince many people in ways that undermine their own interests. Whenever you see anyone resorting to these tricks, you should probably be suspicious of what they’re selling or getting you to support. To be ethical in the way you present arguments in professional situations and steer clear of being held under suspicion by a critical audience yourself, avoid the eight fallacies explored below in Table 15.4.2.

Table 15.4.2: Logical Fallacies to Avoid

| Fallacy | Definition | Example |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Red Herring | Any diversion intended to distract attention from the main issue, particularly by relating the issue to a common fear | So-called "safe" injection sites in our neighborhood will mean that more dealers will set up shop, too, leading to more crime. |

| 2. Straw Man | A weak argument set up to be easily refuted, distracting attention from stronger arguments | Safe injection sites will increase illegal drug use because it'll make those drugs easier to access, defeating the purpose of "harm reduction." |

| 3. Begging the Question | Claiming the truth of the very matter in question, as if it were already an obvious conclusion | Safe injection sites won't save anybody because addicts will continue to overdose with or without them. |

| 4. Circular Argument | A proposition is used to prove itself, assuming the very thing it aims to prove (related to begging the question) | Once a junkie, always a junkie. No "harm reduction" approach will solve the opioid crisis. |

| 5. Bandwagon (a.k.a. Ad Populum) | Appeals to a common belief of some people, often prejudicial, and states everyone holds this belief | No one wants a safe injection site in their neighborhood because they don't care that much about the welfare of drug-addicted criminals. |

| 6. Ad Hominem | Stating that someone's argument is wrong solely because of something about them rather than about the argument itself | The safe injection site advocate is a junkie himself. How can we trust him on issues of safety when every junkie lies as a matter of habit? |

| 7. Non Sequitur | The conclusion does not follow from the premises | Since this whole obsession with being politically correct began 30 years ago, people now think that even addicts are worthy of respect. |

| 8. Post Hoc Ergo Propter Hoc | Establish a cause-and-effect relationship where only a correlation exists | The rise of liberal attitudes since the 1960s has led to higher rates of incarceration across the country. |

(Business Communication for Success, 2015, 14.6)

Avoiding such false logic helps strengthen your own argument by compelling you to stay within the bounds of sound argumentative strategies such as those covered above in §8.4.

Key Takeaway

The quality of any workplace culture depends on the ethical conduct of its leadership and employees, with everyone treating one another with respect and speaking responsibly.

Exercises

- First, think of someone who exemplifies everything you aspire to be in terms of their good behavior in the workplace (loosely defined as anywhere someone does work—not necessarily where it’s compensated with money). List the qualities and actions that make them such a good, well-liked model for behavior. Second, think of someone who exemplifies everything you aspire to avoid in terms of their misconduct in the workplace. List the qualities and typical misbehavior that make them so detestable.

- Deliver a short presentation on dining etiquette or how to dress for success in the workplace with clear recommendations for how your audience should conduct themselves.

- Have you ever experienced or witnessed sexual harassment in a workplace or institution (e.g., at school)? What happened and what did you do about it? Would you do anything differently in hindsight?

- Find an example of advertising that is unethical because it relies on logical fallacies and other deceptive techniques. Identify the fallacies or techniques and speculate on why the advertiser used them. Outline a more honest—yet still effective—advertisement for the same product or service.

Test Your Understanding

References

American Friends Service Committee. (2016, December 2). Do’s and Don’ts for bystander intervention. Retrieved from https://www.afsc.org/resource/dos-and-donts-bystander-intervention

Aufmuth, M. (2018). Tarana Burke. Retrieved from https://www.flickr.com/photos/tedconference/44281895720

Barnes, E. (2018, January 20). Marchers in Baltimore. Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=65692582

Ekman, P. (2017, August 5). Micro expressions. Retrieved from https://www.paulekman.com/resources/micro-expressions/

Feldblum, C.R. & Lipnic, V.A. (2016). Select Task Force on the Study of Harassment in the Workplace. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. Accessed at https://www.eeoc.gov/select-task-force-study-harassment-workplace

Feloni, R., Lee, S., & Cain, Á. (2018, May 16). How to dress your best in any work environment, from a casual office to the boardroom. Business Insider. Retrieved from https://www.businessinsider.com/how-to-dress-for-work-business-attire-2014-8

Frye, V., Camacho-Rivera, M., Salas-Ramirez, K., Albritton, T., Deen, D., Sohler, N., … & Nunes, J. (2020). Professionalism: The wrong tool to solve the right problem?. Academic Medicine, 95(6), 860-863.

The Gandalf Group. (2017, December 12). The 49th quarterly C-suite survey. Retrieved from http://www.gandalfgroup.ca/downloads/2017/C-Suite%20Report%20Q4%20December%202017%20tc2.pdf

Grant, J. M., Motter, L. A., & Tanis, J. (2011). Injustice at every turn: A report of the national transgender discrimination survey. Accessed at http://arks.princeton.edu/ark:/88435/dsp014j03d232p

Hale, T. (2015, April 2). Changing the culture of reporting sexual harassment and sexual assault. Retrieved from https://www.army.mil/e2/c/images/2015/04/02/388160/original.jpg

HRPA. (2018a). Doing our duty: Preventing sexual harassment in the workplace. Retrieved from https://www.hrpa.ca/Documents/Public/Thought-Leadership/Doing-Our-Duty.PDF

HRPA. (2018b). Sexual harassment infographic. Retrieved from https://www.hrpa.ca/Documents/Public/Thought-Leadership/Sexual-Assault-Harassment-Infographic.pdf

Kent State University. (n/d). Dining Etiquette. Kent State University—Career Exploration & Development. Retrieved from https://www.kent.edu/career/dining-etiquette

McClintock, E. A. (2016, March 31). The psychology of mansplaining. Psychology Today. Retrieved from https://www.psychologytoday.com/ca/blog/it-s-man-s-and-woman-s-world/201603/the-psychology-mansplaining

Navigator. (2018, March 7). Sexual harassment survey results. Retrieved from http://www.navltd.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Report-on-Publics-Perspective-of-Sexual-Harassment-in-the-Workplace.pdf

Neal, A., Yeo, G., Koy, A., & Xiao, T. (2011, January 26). Predicting the form and direction of work role performance from the Big 5 model of personality traits. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 33(2), pp. 175-192. Retrieved from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/job.742

Spurk, D., & Abele, A. E. (2010, June 16). Who earns more and why? A multiple mediation model from personality to salary. Journal of Business and Psychology, 26(1), pp. 87-103. Retrieved from https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs10869-010-9184-3

Vescio, T. K., Gervais, S. J., Heiphetz, L., & Bloodhart, B. (2014). The stereotypic behaviors of the powerful and their effect on the relatively powerless (pp. 247–266), in T. D. Nelson (Ed), Handbook of prejudice, stereotyping and discrimination. New York: Psychology Press.

The Washington Center. (2021). What Should I Wear? The Ultimate Guide to Workplace Dress Codes. The Washington Center. Retrieved from https://resources.twc.edu/articles/what-should-i-wear-to-work