Chapter 2: Audience

Veronika Humphries

Chapter Learning Objectives

- Analyze primary and secondary audiences using common profiling techniques.

- Identify techniques for adjusting writing style according to audience size, position relative to you, knowledge of your topic, and demographic.

- Distinguish between communication channels to determine which is most appropriate for particular situations.

- Plan, write, revise, and edit short documents and messages that are organized, complete, and tailored to specific audiences.

2.1: Analyzing Your Audience

Section 2.1 Learning Objectives

- Analyze primary and secondary audiences using common profiling techniques.

- Identify techniques for adjusting writing style according to audience size, position relative to you, knowledge of your topic, and demographic.

- Plan, write, revise, and edit short documents and messages that are organized, complete, and tailored to specific audiences.

Profiling or analyzing your audience takes skill and consideration. When you sit down to write, ask yourself the following questions:

- What is the size of my main audience? Is it one person, two, a few, several, a dozen, dozens, hundreds, or an indeterminately large number (the public)?

- Who might my secondary or tertiary audiences be (e.g., people you can see copied on an email or people you can’t because they could have forwarded your email without your knowledge)?

- What is my professional or personal relationship with them relative to their position/seniority in their organization’s hierarchy?

- How much do they already know about the topic of my message?

- What is their demographic—i.e., their age, gender, cultural background, educational level, and beliefs?

The following subsections delve further into these considerations to help you answer the above questions in specific situations.

- 2.1.1: Writing for Audiences of Various Sizes

- 2.1.2: Secondary Audiences

- 2.1.3: Considering Your Relationship to the Audience and Their Position

- 2.1.4: Considering Your Audience’s Level of Knowledge

- 2.1.5: Audience Demographics

2.1.1: Writing for Audiences of Various Sizes

Writing to one person is a relatively straightforward task, but you must adjust your writing style to accommodate a larger audience. When emailing one person, for instance, you can address the recipients by name in the opening salutation and continue to use the second person singular “you” throughout the rest of your message. Two or three recipients should be individually addressed but past four, you may start to use collective salutations such as “Hello, team,” or “Hi, all.” For a small audience, your style can generally follow the conversational rapport you’ve developed with them, whether that be formal or informal, humorless or humorous, literal or expressive, and so on.

The larger the group, however, the more general and accessible your language has to be. When writing for an indeterminately large group such as the consumer public (a blog on your company’s website), your language must be as plain and accessible as possible. In the United States, the public includes readers who will appreciate that you use simple words rather than big, fancy equivalents because English may be their second or third language.

Use familiar language, known as expressions and illustrations:

- Choose familiar, everyday words and expressions (e.g., “quite” rather than “relatively”)

- Define specialized words and difficult concepts, illustrate them with examples and provide a glossary when it is necessary to use several such words/concepts

- Choose concrete rather than abstract words and give explicit information (e.g., “car crash” rather than “unfortunate accident”)

- Avoid jargon and bureaucratic expressions

- Use acronyms with care and only after having spelled them out

- Choose one term to describe something important and stick to it; using various terms to describe the same thing can confuse the reader

- Add tables, graphs, illustrations and simple visual symbols to promote understanding

The larger the group, the more careful you must be with using unique English idioms. Idioms are quirky or funny expressions we use to make a point. For example, if you wanted to reassure a customer who recently immigrated from North Africa, explaining an automotive maintenance procedure unique to winter weather in Maine and saying, “Hey, don’t worry, it’ll be a piece of cake,” they may be wondering what eating cake has to do with switching to winter tires. Likewise, if you said that it’ll be “a walk in the park,” they would be confused about why they need to walk through a park to get their radials switched. Calling it a “cakewalk” wouldn’t help much, either. These expressions would be perfectly understood by anyone who has been conversing in English for years because they would have heard them many times before and used them themselves. In the case of using them around ESL (English as a second language) speakers, however, you would be better off using the one word that these idioms translate to, which is the word “easy”. Again, the whole goal of communication is to be understood, so if you use idioms with people who haven’t yet learned them, you will fail to reach that goal. See The Idioms for a wide selection of English idioms and their meanings.

2.1.2: Secondary Audiences

Always consider secondary or even tertiary audiences for any message you send. Although secondary audiences you may have included in your message are designated as recipients, you have little-to-no control over what tertiary audiences see your message. Your emails can be forwarded, your text or voicemail messages shown or played, and even the words alone can simply be reported to tertiary audiences. Youth who are more comfortable writing electronically than speaking in person often make the mistake of assuming privacy when sending messages and get burned when those messages fall into the wrong hands—sometimes with surprising legal consequences related to bullying or worse. Before sending that email or text, or leaving a voicemail in professional situations, however, always consider how your manager, your family, or a jury would perceive the conversation.

You may think that you have a right to privacy in communication, and you do to some extent, but employers also have certain rights to monitor their employees and ensure company property (including cyber property) isn’t being misused (Lublin, 2012). A disgruntled employee, for instance, uses their company email account in communication with a rival company to prove that they are part of a target company. The same employee later uses that email account to sell trade secrets before leaving for another job. The employer has a right to read both of these emails and take measures to protect against such corporate espionage. Because company emails can be stored on the organization’s servers, always assume that any email you send using a company account can be retrieved and read by tertiary audiences (such as auditors or law enforcement). If you are at all concerned that an email might hurt you if it fell into the wrong hands, arrange to talk to the primary audience on a channel that won’t be so easily monitored.

Even in more harmless and routine information sharing, you must adjust your message for any known or unknown secondary audiences. If you copy your supervisor or other stakeholders in your email, you will be even more careful to avoid any mistakes, since a poorly written message is a direct reflection of you. Your style will be a little more formal and you will proofread more thoroughly to avoid writing errors that make you appear uneducated and sloppy, which no employer wants to pay for.

Even if you don’t designate other recipients, as explained above, someone else could. For example, you might be in a back-and-forth email thread with a co-worker as you collaborate on a project. You’re making good progress at first, but your partner begins slacking off and your emails become progressively impatient, even angry and threatening. Frustrated, you enlist another collaborator who, towards the end of the thread as drafts are exchanged with finishing touches, copies your manager to show that the work is completed. Seeing the lack of professionalism in your exchanges with the previous collaborator when trying to assess what discipline may be necessary, your manager now sees that you must share some of the blame for your poor communication choices.

Of course, internet etiquette or netiquette requires that you be careful with whom you CC on messages. Often managers will be interested in what’s going on with certain projects and would like to be copied to be kept in the loop. In such cases, clarify with them to what extent they want to see the progress; copying them on every little exchange will just waste their time and annoy them by flooding their inbox. Involving them only when important milestones are met, however, will be much appreciated.

Reference

Lublin, D. (2012, November 8). Do employers have a right to spy on workers? The Globe and Mail. Retrieved from https://beta.theglobeandmail.com/report-on-business/careers/career-advice/experts/do-employers-have-a-right-to-spy-on-workers/article5104037/?ref=http://www.theglobeandmail.com&

2.1.3: Considering Your Relationship to the Audience and Their Position

Just as you might wear your best clothes for an important occasion such as a job interview or wedding, you must respectfully elevate the formality of your language depending on the perceived importance of the person you’re communicating with. As said above, if you’re writing to your manager about something very important, something that will be read closely perhaps by many people, you would be more careful to write in a professional style and fully proofread your email than you would if you were writing a co-worker who doesn’t really care about the odd spelling mistake. Employers or clients will create their personal judgment based on your writing and can deem you careless if they receive a poorly written email from you. Employers prefer detail-oriented and precise employees, which includes products of writing because they represent the company to customers and other stakeholders (Wiens, 2012). Ultimately, you don’t want to embarrass yourself and lose a chance on professional opportunities with glaring writing mistakes that more thorough proofreading could have caught.

Formality in writing requires correct grammar, and punctuation, and it involves carefully selecting words that are more professional than the colloquial (“informal”) words you would normally use in everyday situations. Word choice or diction requires that you use a thesaurus to find words with meanings equivalent to the simpler words that come to mind (called “synonyms”), then always use a dictionary to ensure that the synonym is the correct choice in the context you’re using it. When writing to a relatively non-judgmental co-worker whom you’ve become good friends with, you tend to write more casually with plain words that are possibly even slightly slangy for comic effect. When writing someone higher up in your organization’s hierarchy, however, you would probably choose skillfully selected words along the formality spectrum, yet not so fancy as to come off as pretentious and trying to make them feel unintelligent by forcing them to look at the words in the dictionary. Such obfuscation wouldn’t be reader-friendly and accomplish the basic communication goal of being understood, as you might realize right now if you don’t know what the word obfuscation means (it means the act of intentionally making your meaning unclear to confuse your audience).

On most occasions, especially with customers, you should aim to strike a balance with a semi-formal style somewhere between overly formal and too casual. Your writing should read much like you speak in conversation, although it must be grammatically correct.

| Informal / Slang | Semi-formal / Common | Formal / Fancy |

|---|---|---|

| kick off | begin/start | commence |

| cut off | end | terminate |

| put off | delay | postpone |

| awesome / dope | good | positive |

| crappy / shoddy | bad | negative |

| flaunt | show | demonstrate |

| find out | discover | ascertain |

| go up | rise | increase |

| fess up / come clean | admit | confess |

| mull over | consider | contemplate |

| bad-mouth / put down | insult / belittle | denigrate |

| plus | also | moreover |

| jones for | need | require |

| put up with | endure/suffer | tolerate |

| leave out / skip | omit | exclude |

| give the go-ahead / greenlight | permit | authorize |

| loaded / well-heeled | wealthy / rich | affluent / monied |

| deal with | handle | manage |

| pronto / a.s.a.p. | now | immediately |

| muddy | confuse | obfuscate |

Table 2.1.3: Word Choices along the Formality Spectrum

Reference

Wiens, K. (2012, July 20). I Won’t Hire People Who Use Poor Grammar. Here’s Why. Harvard Business Review. Retrieved from: https://hbr.org/2012/07/i-wont-hire-people-who-use-poo

2.1.4: Considering Your Audience’s Level of Knowledge

A key step when analyzing your audience is to think about how much the recipient of your message already knows about the topic you are about to discuss. Your goal is to provide ample explanation so that the receiver will not have any additional clarifying questions. On the other hand, you do not want to restate so much information that the reader already knows. A safe assumption with everyone you deal with in professional situations is that they’re busy and don’t have time to read any more than they need to. If you overexplain a topic in an email, you make the double mistake of wasting the reader’s time and insulting them by presuming their ignorance. Additionally, this becomes a triple mistake considering the time you wasted in writing more than you had to.

On the other end of that spectrum, it is also an inconvenience to not provide enough information. A lack of necessary information in a message ultimately leads to either errors due to confusion or wasted time from having to respond with requests for clarification or, worse, damage control because your reader acted on misunderstandings resulting from your miscommunication. Either way, the goal of communication (for the receiver to understand information as it was understood by the sender) isn’t met by the message.

Appropriately assessing your audience’s level of knowledge extends to the language you use. Every profession has its jargon, which is the specialized vocabulary, shorthand code words, and slang that you use amongst colleagues with the same discipline-specific education as you. Jargon saves time by making elaborate descriptions unnecessary, so it’s useful among people who speak the same language. But some professionals err by using jargon with customers and even employers who don’t know the lingo. At worst, this puts those audiences in the uncomfortable position of feeling ignorant of something perhaps they should know about, leading to confusion; at best it leads to opportunities for educating those audiences so they can use the same jargon with you.

Effective document design can also aid in understanding for those who may have difficulty with reading comprehension, as well as for those who are competent professionals but are just busy. When explaining a procedure, for instance, using a numbered list rather than a paragraph description helps the reader skim to find their spot when going back and forth between your instructions and performing the procedure itself.

Brief, bolded headings and subheadings for discreet topics within a document also orient readers looking for specific information, as you can see from scanning through this textbook. If this chapter contained no such headings and instead was just a ream of paragraphs as in a novel, finding this section using the Table of Contents and index alone would probably double or triple the time it takes to narrow down where it begins and ends.

2.1.5: Audience Demographics

It is also necessary to adjust your message based on your audience’s level of education, age group, or profession, as described earlier. Depending on your profession, you may have to deal with people of all ages and levels of education from elementary school children to retirees.

Sometimes judging levels of understanding can be difficult and lead to trouble when done in error, so tact and emotional intelligence are essential. It can be downright insulting if you speak to an elderly person as you would to a child because you assume that their coherence is diminished when in fact the opposite is true. Don’t be surprised if your condescension is met with a sassy kickback if you make that mistake. But if you speak to an elderly person as you would a middle-aged adult despite their having severe hearing loss and undiagnosed early-onset dementia, this will also lead to failures in communication and understanding. So, what are we to do, then?

The key to determining the level of one’s understanding is always to begin communication with a mid-level diction and conversational tone in your opening message, then adjust based on the feedback message, which includes both a verbal or written response and nonverbal clues (if communicating in person). In-person, nonverbal feedback such as a briefly furrowed brow of confusion helps to determine if a message is misunderstood. A slight eye-roll subtly informs you that you’ve started off too basic and need to step up to a more advanced level. Sometimes you can even “see” these expressions in writing by reading between the lines of a response that indicates a more advanced understanding than you assumed.

If your correspondent’s writing style similarly betrays a lack of education—for whatever reason—through numerous grammatical, spelling, and punctuation errors, then you know to adjust your own style to use more plain expressions accommodating someone with a more basic reading level. In such cases, be understanding rather than assume that the person is merely dim-witted. They could be:

- Extremely intelligent but English is their second or third language and they’re still in the process of learning it

- Extremely intelligent at some things but just not at writing

- Very young and still learning how to write

- Elderly and either out of practice or losing their faculties

- Affected by any number of learning disabilities of varying severity

- Good writers and smart, but in a terrible rush

Make sure to avoid reaching conclusions. Rather, respond without judgment to someone who writes poorly, but do so in a plain, accessible style using familiar words and fully explaining your topic.

Being nonjudgmental as well as respectful towards those of different cultures and religious beliefs is also key to effective communication. If you are committed to a belief system yourself, never assume that everyone else shares your views or is wrong for believing otherwise. Even if you are not religious per se, you still have a belief system shaped by the culture in which you developed. Everyone’s belief system is the result of life experiences that differ from those of others; unless that system drives them towards anti-social behavior or even violence, nothing is wrong with holding those beliefs as far as you’re concerned. In your writing, always be understanding towards others’ beliefs; don’t belittle or insult them.

Key Takeaway

Knowing your audience by their size, position relative to you, knowledge of your topic, and demographic helps you craft your message content and style to meet their needs.

Exercises

- List at least three demographic traits that apply to you. How does belonging to these demographic groups influence your perceptions and priorities? Share your thoughts with your classmates.

- Recall a time when you started a new job and learned the jargon of the workplace—words that the general public wouldn’t know the meaning of, or at least the meanings you attached to them. Write a glossary listing as many such jargon words as you can along with their definitions (how you would explain them to the public). Share a few with the class. (If you’ve never been employed, use a volunteer, sports, or other group activity you’ve engaged in.)

- Review the last email you wrote. Is it written formally or informally? If informal, revise it so that it is more formal as if you were to send it to a manager or client; if formal, revise it so that it is more informal as if you were to send it to a trusted co-worker. (If you want your most recent email to remain private, search back for the one you wouldn’t mind sharing. Include the original email in your submission.)

2.2: Message Channel Selection

Section 2.2 Learning Objectives

- Distinguish between communication channels to determine which is most appropriate for particular situations.

- Plan, write, revise, and edit short documents and messages that are organized, complete, and tailored to specific audiences.

2.2.1: Common Workplace Communication Channels

Throughout this chapter, we’ve been considering messages sent via email because it is the most common channel for written business messages. However, many professionals make the mistake of sending an email when another channel (e.g., a verbal rather than a written one) would be more appropriate for the situation and the audience. If you had to deal with inappropriate behavior in the workplace, for instance, the right thing to do is discuss it in person with all involved because conflict resolution requires social intelligence enhanced by all the verbal and nonverbal information you can gather from them. You could follow up with an email summarizing a remedial action plan reached through constructive dialogue, but you would never deal with the situation by email alone.

Addressing sensitive situations exclusively by email (or, even worse, text message) tends only to intensify a conflict. Email or messaging can’t possibly address the emotional complexity of a difficult situation and usually results in costly delays given the time lag between responses. Tensions also tend to escalate when people have the time to read too much into emails and text or instant messages about sensitive topics, misinterpret their tone, and write angry or passive-aggressive ones in return. (Many people tend to lack filters when writing electronically in a state of heightened emotion because they feel relatively free to express the internal monologue that they would otherwise restrain if in the physical company of the person they’re writing to.) Email is only one of many channel options and although the most popular and widely used one, always consider other options before making the decision on how to address your audience most effectively and efficiently.

Between traditional and rapid electronic media, we have more choices for communication channels than ever in human history. Each has its own unique advantages and disadvantages that make it appropriate or inappropriate for specific situations. Knowing those pros and cons, summarized below for a dozen of the most common verbal and written channels available, is necessary for being an effective communicator in the modern workplace. Choosing channels wisely can mean the difference between a message that is received and understood as intended (the goal of communication), and one that is lost in the noise or misunderstood in costly ways.

2.2.1: Common Workplace Communication Channels

The following is a list of communication channels from the richest to the poorest in terms of feedback. In-person communication provides the richest feedback because you see the person you are communicating with and speak to them in real-time (without any delays in responses). You can see their facial expressions, their body language, and hear their tone of voice, which gives you the opportunity to adjust your message appropriately based on what you see and hear. A report provides the poorest feedback because you cannot see the person’s reactions while reading it. If it is a long report, it may take a long time before you receive any response and therefore it is impossible to adjust your communication in any way after the report has already been submitted.

- In-person conversation and group meeting

- Video chat and web conference

- Phone, VoIP, voicemail, and conference calls

- Instant/text message

- Memo

- Letter

- Report/PowerPoint

Channel: In-person conversation and group meeting

Advantages: It is the most information-rich channel combining words and nonverbal messages; facilitates immediate back-and-forth exchange of ideas; maintains the human element lacking in most other channels, and additional participants can join for group discussion.

Disadvantages: The speakers must be physically in the same space together; people have different levels of verbal communication and listening skills; the results of the conversation are not permanent unless recording equipment is used.

Expectations: The audience must be present and attentive rather than distracted by their mobile technology or multitasking; a dynamic speaking ability is required to engage audiences.

Appropriate Use: Quickly exchange ideas with people close by; visually communicate to complement your words; add the human element in discussing sensitive or confidential topics that need to be worked out through dialogue.

Channel: Video chat and web conference

Advantages: Enables face-to-face, one-on-one, or group meetings for people physically distant from one another (anywhere from across town to the other side of the planet); allows participants to see non-verbals that would be unseen in a phone conference meeting; can be integrated into a real in-person meeting to include physically absent members; inexpensive with common applications such as Zoom, Skype, FaceTime (for Apple devices), and Google Talk; more cost-effective than flying people around to conduct routine meetings.

Disadvantages: Connection problems often result in poor audio quality (cutting in and out) and split-second delays that result in misleading nonverbal cues and participants talking over one another; enterprise applications improve functionality but for a higher cost.

Expectations: Requires a high-speed internet connection, microphone, and webcam all in good working order; requires that participants be as present and presentable (at least from the waist-up) as they would be for an in-person meeting; participants must control their background surroundings, especially when web conferencing from home, to avoid interruptions.

Appropriate Use: Ideal when in-person meetings are necessary but participants are in different physical locations; often used for job interviews when participants cannot conveniently attend in person.

Channel: Phone, VoIP, voicemail, and conference calls

Advantages: Enables audio-only dialogue between speakers anywhere in the world; quick back-and-forth saves time compared to written dialogue by email or text; can send one-way voicemail messages or leave them when the recipient isn’t available; can be conducted cheaply over the internet (with Voice over Internet Protocol) and easily on smartphones; specialized phone equipment and VoIP enable conference calls among multiple users.

Disadvantages: Absence of nonverbal visual cues can make dialogue occasionally difficult; the receiver of a call isn’t always available, so the timing must be right on both ends; if not, availability problems lead to “phone tag”; time zone differences complicate the timing of long-distance calls; possibly expensive for long-distance calls over a public switched telephone network (PSTN) if VoIP isn’t available; limited length of the voicemail message; recording of conversations is typically unavailable unless you have special equipment.

Expectations: Follow conventions for initiating and ending audio-only conversation; for voicemail, strike a balance between brevity and providing a thorough description of the reason for the call and your contact information; record a professional call-back message for voicemail when not available to take a call; respond to voicemail as soon as possible since you were called with the hope that you would be available to talk immediately; be careful with confidential information over the phone, and don’t discuss confidential information via voicemail.

Appropriate Use: When quick dialogue is necessary between speakers physically distant from one another; use conference call when members of a team can’t be physically present for a meeting; use VoIP to avoid long-distance charges; leave clear voicemail messages when receivers aren’t available, when a record of the conversation isn’t necessary, or when confidentiality is somewhat important.

Channel: Email

Advantages: Delivers messages instantly anywhere in the world to anyone with an internet connection and email address; can be sent to one or many people at once, including secondary audiences CC’d (copied) or BCC’d (blind copied); allows you to attach documents up to several megabytes in size or links to any internet webpages; allows for a back-and-forth thread on the topic in the subject line; archives written correspondence for review even decades later; can be done on any mobile device with an internet connection; is cost-effective (beyond your subscription fees to an internet or phone provider); is somewhat permanent in that emails exist somewhere on a server even if deleted by both sender and receiver.

Disadvantages: Gives the illusion of privacy: your messages can be forwarded to anyone, monitored by your company or an outside security agency, retrieved with a warrant, or hacked even if both you and the receiver delete them; can provide delayed feedback when used for back-and-forth dialogue; tone may be misread (e.g., jokes misunderstood) due to the absence of nonverbal cues; may be sent automatically to the recipient’s spam folder or otherwise overlooked or deleted without being read given the volume of emails some people get in a day; subject to errors such as clicking “send” prematurely or replying to all when only the sender should be replied to; subject to limits on document attachment size; subject to spam (unsolicited emails); regretted emails can’t be taken back or edited; requires a working internet connection on a computing device, which isn’t available everywhere in the world.

Expectations: Reply within 24 hours, or sooner if company policy requires it; follow conventions for writing a clear subject line, salutation, message opening, body and closing, closing salutation, and e-signature; netiquette: be as kind as you should be in person; don’t write emails angrily; edit to ensure coverage of the subject indicated in the subject line with no more or less information than the recipient needs to do their job; proofread to ensure correct grammar, punctuation, and spelling because errors compromise your credibility; avoid confusion due to vagueness that requires that the recipient respond asking for clarification.

Appropriate Use: Quickly deliver a message that doesn’t need an immediate response; send a message and receive a response in writing as evidence for future review (provide a paper trail); use when confidentiality isn’t necessary; send electronic documents as attachments; send the same message to several people at once, including perhaps people whose email address you need to hide from the others (using BCC) to respect their confidentiality.

Channel: Instant/text message

Advantages: Enables the rapid exchange of concise written messages; can be done quietly to not be overheard; inexpensive; autocomplete feature helps achieve efficiencies in typing speed and spelling; nonverbal characters such as emojis can clarify tone; many instant message applications are available, such as Facebook Messenger, Google Talk, WhatsApp, and Snapchat.

Disadvantages: Often used to avoid human contact when the telephone or in-person communication is available and more appropriate; encourages informality with lazy abbreviations, initialism, and acronyms; even with autocomplete, typing with thumbs alone can be slower than using 10 fingers on a desktop or laptop computer; concise text alone can be misinterpreted for tone when used to summarize complex ideas; other non-verbals such as emojis help clarify tone, but also undermine credibility if used in professional situations; give the illusion of privacy: texts exist on servers and can be retrieved even if deleted by both sender and receiver; mobility and portability of texting devices tempt users with poor impulse control to text dangerously while walking or driving, or rudely in front of people talking to them.

Expectations: Respond immediately or as soon as possible, since the choice to text or IM is usually for rapid exchange of information; be patient if the recipient doesn’t respond immediately, they may be busy with real-life tasks; proofread when used for professional purposes as confusion due to writing errors can be costly when acted upon immediately; use only when able; never text when driving because the distraction turns your vehicle into a lethal weapon; never text when walking because you get in people’s way, hit obstacles yourself, and look like an addict to technology.

Appropriate Use: Use for exchanging short messages quickly with someone physically distant; get an information exchange in writing for reference later; use when confidentiality isn’t important.

Channel: Instagram

Advantages: Instagram for Business provides branding visuals for interested customers, especially millennials; allows customers to respond in real-time.

Disadvantages: The audience is largely limited to a younger demographic with limited spending power; means of expression is limited to photos and brief captions; can undermine professional credibility if used for selfies, which make you appear juvenile and overly self-involved; inconvenient if posting and managing an account from a laptop or desktop computer rather than a smartphone; doesn’t provide an easy way to link to a company website to provide audiences with further information.

Expectations: Use for providing visuals of company products or services rather than for individual self-promotion with selfies; strike a balance in posting frequency—not too seldom, not too often; include as part of a marketing mix that includes other social media such as Facebook and Twitter.

Appropriate Use: Post company photos to reach younger demographics.

Channel: Letter

Advantages: Shows respect through formality and effort; ensures confidentiality when sealed in an envelope and delivered to the recipient’s physical address (it is illegal to open someone else’s mail); can introduce other physical documents (enclosures).

Disadvantages: Slow to arrive at the recipient’s address depending on how far away they are from the sender; can be intercepted or tampered with in transit (albeit illegally); can be overlooked as junk mail; time-consuming to print, sign, seal, and send for delivery; mail postage is costlier than email.

Expectations: Follow conventions for different types of letters (e.g., block for company letters, modified block for personal letters) and provide the sender’s and recipient’s address, date, recipient salutation, closing salutation, and author’s signature; use company letterhead template when writing on behalf of your organization.

Appropriate Use: For providing a formal, permanent, confidential written message to a single important person or organization; ideal for job applications (cover letter), persuasive messages (e.g., fundraising campaigns), bad-news messages, matters with possible legal implications (e.g., claims), and responses to letters; for non-urgent matters.

Channel: Memo

Advantages: Provides a written record of group decisions, announcements, policies, and procedures within an organization; can also be a format for delivering small reports (e.g., conference report) and recording negotiating terms in agreements between organizations (e.g., memo of understanding); can be posted on a physical bulletin board and/or email.

Disadvantages: Requires a good archiving system to make memos easily accessible for those (especially new employees) needing to review a record of company policies, procedures, etc.; doesn’t provide immediate reader feedback or reaction.

Expectations: Use template with company letterhead; follow the same conventions as email, except omit the opening and closing salutations and e-signature.

Appropriate Use: For a written record for decisions, announcements, policies, procedures, and small reports shared within an organization; post a printed version on an office bulletin board and email it to all involved.

Channel: Report/PowerPoint

Advantages: Allows presentation of a high volume of information presenting research and analysis; can take various forms such a document booklet or proposal for reading alone or PowerPoint for presenting.

Disadvantages: Time-consuming to write with proper research documentation and visual content, as well as to prepare for (presentations); time-consuming for the busy professional to read or an audience to take in; presentations can bore audiences if not engaging.

Expectations: Follow conventions for organizing information according to the size of the report, audience, and purpose; enhance with visuals; engage audiences with effective oral delivery and visual appeal.

Appropriate Use: For providing thorough business intelligence on topics important to an organization’s operation; for internal or external audiences; for persuading audiences with well-developed arguments (e.g., proposal reports).

Selecting the correct communication channel on the spectrum of options using the criteria above involves a decision-making process based on the purposes of the communication, as discussed earlier in this chapter. Factors to consider include convenience for both the sender and receiver, timeliness, and cost in terms of both time and money. When choosing to send an email, for instance, you:

- Begin with the thought you need to communicate

- Decide that it must be in writing for future reference rather than spoken

- Consider that it would be more convenient if it arrived cheaply the instant you finished writing it and hit Send

- Want to give the recipient the opportunity to respond quickly or at least within the 24-hour norm

- Decide that it would be better to send your message by email rather than by other electronic channels such as text, instant message (because you have more to say than would fit in either of those formats), or fax because you know most recipients prefer email over fax

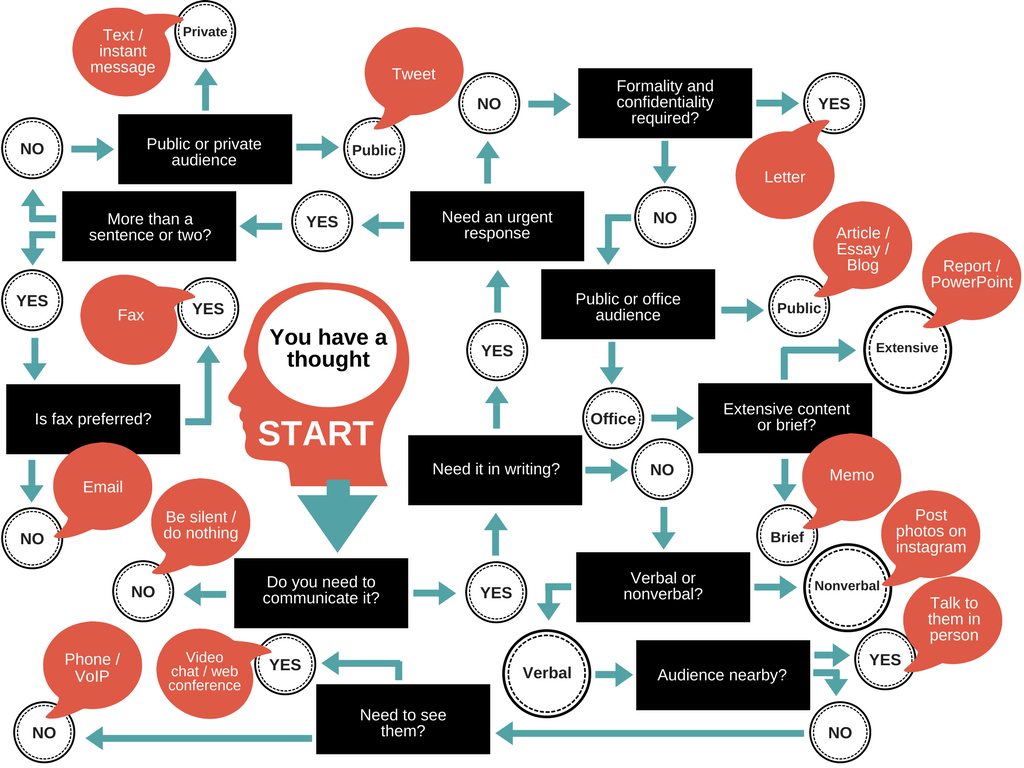

All of these decisions may occur to you in the span of a second or so because they are largely habitual. Figure 2.2 charts the decision-making process for selecting the most appropriate channel among the 10 given in section 2.2.1 above.

Figure 2.2: Channel selection process flow chart

Click here for an interactive and accessible version of the Channel Selection Flow Chart

The uses, misuses, conventions, and implications of these channels will be discussed in the chapters ahead, especially Chapters 6–8 on written documents and Chapters 10–11 on oral communication. For now, however, let’s appreciate that choosing the most appropriate channel at the beginning of the writing process saves time—the time that you would otherwise spend correcting communication errors and doing damage control for having chosen the wrong one for the situation at hand.

Key Takeaway

Choose the most appropriate communication channel for the occasion by taking into account the full spectrum of traditional and electronic means, as well as your own and your audience’s needs.

Exercises

Identify the most appropriate channel for communicating what’s necessary for the given situation and explain your reasoning.

- You come up with a new procedure that makes a routine task in your role in the organization quicker and easier; praise for your innovation goes all the way up to the CEO, who now wants you to meet with the other employees in your role in the seven other branch offices across the country to share the procedure.

- A customer emails you for a price quote on a custom job they would like you to do for them. (Your company has a formal process for writing up quotes on an electronic form that gives a price breakdown on a PDF.)

- You are working with two officemates on a market report. Both have been bad lately about submitting their work on time and you’re starting to worry about meeting the next major milestone a few days from now. Neither has been absent because you can see them in their offices as you walk by in the hallway.

- You are about to close a deal but need quick authorization from your manager across town about a certain discount you would like to apply. You need it in writing just in case your manager forgets about the authorization or anyone else questions it back at the office.

- Your division recently received word from management that changes to local bylaws mean that a common procurement procedure will have to be slightly altered when dealing with suppliers. Your team meets to go over the changes and the new procedure, but you need to set it down in writing so that everyone in attendance can refer to it, as well as any new hires.

- You have a limited amount of time to discuss a potential funding opportunity with a colleague in another city because the proposal deadline is later in the week and it’s almost closing time in your colleague’s office. You’ll have to hammer out some details about who will write the various parts of the proposal before you get to work on it tonight.

- You were under contract with a local entrepreneur to perform major landscaping services. Near the end of the job, you discovered that he dissolved his company and is moving on, but you haven’t yet been paid for services rendered. You want to formally inform him of the charges and remind him of his contractual obligations; in doing so you want to lay down a paper trail in case you need to take him to court for breach of contract.

Test Your Understanding