Chapter 6: Routine Messages

Veronika Humphries

Chapter Learning Objectives

- Plan, write, revise, and edit short documents and messages that are organized, complete, and tailored to specific audiences.

- Write routine message types such as information shares, requests, and replies; complaints and claims; and recommendation and goodwill messages.

- Organize and write persuasive messages.

- Organize and write negative messages.

The vast majority of business messages sent daily are routine so-called positive messages sharing information, requesting action, or thanking someone for something. Most of these messages are positive or neutral in content, even if they may involve minor complaints or claims where the sender requests an error correction. All these messages are direct-approach messages. The main idea or request is listed at the beginning of the message with more details and explanations described later in the message. In situations when you must describe a delicate situation or something involving negative news, you should follow an indirect approach.

- 6.1: Positive Messages: Information, Requests, and Replies

- 6.2: Complaints and Claims

- 6.3: Negative Messages

6.1: Positive Messages: Information, Requests, and Replies

Section 6.1 Learning Objectives

- Plan, write, revise, and edit short documents and messages that are organized, complete, and tailored to specific audiences.

- Write routine message types such as information shares, requests, and replies.

Most business professionals would agree that most messages they compose at work concern requests for information or action and reply to such requests by providing answers and acknowledgments. Although you have likely written many such messages already, you may need help to polish the professional style, vocabulary, and organization of your messages to meet a professional business standard and to achieve your goal successfully. It is important to ask or request something concisely but clearly, providing correct and enough information so that the person requesting the information will not have to ask clarifying questions. A few scenarios with examples are described below.

6.1 Positive Messages: Information, Requests, and Replies Topics

- 6.1.1: Providing Information

- 6.1.2: Requests for Information or Action

- 6.1.2.1: Instructional Messages

- 6.1.3: Replies to Requests

6.1.1: Providing Information

Perhaps the simplest and most common routine message type is where the sender offers information that helps the receiver. These may not be official memos, but they follow the same structure, as shown in Table 6.1.1 below.

Table 6.1.1: Outline for Information Shares

| Outline | Content | Example Message |

|---|---|---|

| Opening | Main point of information |

Hi Karin, I just saw a CFP for a new funding opportunity you can apply for via the Department of Agriculture. |

| Body | Information context and further details | Find it on the Greenbelt Fund’s Local Food Literacy Grant Stream page. If you haven’t already been doing this, you should also check out the Ministry’s general page on Funding Programs and Support to connect with any other grants, etc. relevant to the good work you do. |

| Closing | Action regarding the information | It looks like the deadline for proposals is at the end of the week, though, so you might want to get on it right away.

Good luck! Shradha |

The writer made the reader’s job especially easy by providing links to the recommended web pages using the hyperlinking feature (Ctrl + K) in their email. Replies to such information shares involve either a quick and concise thank-you message (see §6.1.3 below) or continuing the conversation if it is part of an ongoing project or initiative. You should change the email subject line as the topic evolves (see §6.1.2 below). Information shared with a large group, such as a departmental memo to 60 employees, doesn’t usually require acknowledgment. If everyone wrote the sender just to say thanks, the barrage of reply notifications would frustrate them. They try to carry on their work while sorting out replies with valuable information from mere acknowledgments. Only respond if you have helpful information to share with all the recipients or just the sender.

6.1.2: Requests for Information or Action

Managers, clients, and coworkers alike send and receive requests for information and action all day. Because these provide the recipient with direction on what to do, the information that comes back or activity that results from such requests can only be as good as the instructions given. Therefore, such messages must be well organized and clear about expectations, opening directly with a clearly stated general request. On the other hand, if you anticipate resistance to the request, you should compose and organize your message in the indirect approach—and then proceed with background and more detailed instruction if necessary (as we see in Table 6.1.2 below).

Table 6.1.2: Outline for Direct Information or Action Requests

| Outline | Content | Example Message |

|---|---|---|

| Subject Line | 3- to 7-word title | Website update needed by Monday |

| 1) Opening | Main question or action request | Hello, Mohamed:

Could you please update the website by adding the new hires to the Personnel page? |

| 2) Body | Information or action request context, plus further details | We’ve hired three new associates in the past few weeks. With the contents of the attached folder that contains their bios and hi-res pics, please do the following:

|

| 3) Closing | Deadlines and/or submission details | Sorry for the short notice, but could we have this update all wrapped up by Monday? We’re meeting with some investors early next week and we’d like the site to be fully up to date by then.

Much appreciated! Sylvia |

Note that the opening question doesn’t always require a question mark because you are expecting action as a result of the request rather than a Yes or No answer. Never forget, however, the importance of saying “please” when asking someone to do something (see §6.1.2 above for more on courteous language). Notice that using a list of requests in the message body helps break up dense detail so that request messages are more reader-friendly (see §6.1.2 above). All the efforts that the writer of the above message made to deliver a reader-friendly message will pay off when the recipient performs the requested procedure exactly according to these worded expectations.

6.1.2.1: Instructional Messages

Effective organization and style are critical in requests for action that contain detailed instructions. Whether you’re explaining how to operate equipment, apply for funding, renew a membership, or submit a payment, the recipient’s success depends on the quality of the instruction. Vagueness and a lack of detail can result in confusion, mistakes, and requests for clarification. Too much detail can result in frustration, skimming, and possibly missing critical information. Profiling the audience and gauging their level of knowledge is vital (see Chapter 2 above on analyzing your audience) to provide the appropriate detail level for the desired results. Look at any assembly manual, and you’ll see that the quality of its readability depends on the instructions being organized in a numbered list of parallel imperative sentences. Though helpful, the above message would be much improved if it included illustrative screenshots at each step. Making a short video of the procedure, posting it to YouTube, and adding the link to the message would be even more effective.

Combining DOs and DON’Ts is an effective way to help your audience complete the instructed task without making common mistakes. Always begin with the DOs after explaining the benefits or rewards of following a procedure, not with threats and heavy-handed Thou shalt nots. Most people are better motivated by chasing the carrot than fleeing the stick. If necessary, you can certainly follow up with helpful DON’Ts and consequences, but phrased in courteous language, such as “For your safety, please avoid operating the machinery when not 100% alert or you may risk serious harm.”

6.1.3: Replies to Requests

When responding to information or action requests, simply deliver the needed information or confirm that the action has been completed unless you have good reasons for refusing. Stylistically, such responses should follow the 6 Cs of effective business style, especially courtesies such as prioritizing the “you” view and audience benefits and saying “please” for follow-up action requests. Such messages also provide opportunities to promote your company’s products and services. However, ensure the accuracy of all details because if disputes arise, courts will consider them legally binding, even if this information was only described in an email. Therefore, manager approval may be necessary before sending, especially if you are not authorized to initiate or approve bids or negotiate contracts. Organizationally, a positive response to an information request delivers the main answer in the opening, proceeds to give more detail in the body if necessary, and ends politely with appreciation and goodwill statements, as shown in Table 6.1.3 below.

Table 6.1.3: Outline for Positive Replies to Information or Action Requests

| Outline | Content | Example Message |

|---|---|---|

| Subject Line | 3- to 7-word title | Re: Accommodation and conference rooms for 250 guests |

| 1) Opening | Main information or action confirmation | Greetings, Mr. Prendergast:

Thank you so much for choosing the JW Marriott New Orleans for your spring 2023 sales conference. We would be thrilled to accommodate 250 guests and set aside four conference rooms next May 25 through 29. |

| 2) Body | Further details | In answer to your other questions:

|

| 3). Closing | Deadlines and/or action details | You can visit our website at www.marriott.com for additional information about our facilities such as gyms, a spa, and both indoor and outdoor swimming pools. Call us at 1-504-525-6500 if you have additional questions.

Please book online as soon as possible to ensure that all 250 guests can be accommodated during your preferred date range. For such a large booking, we encourage you to call also during the booking process. Again, we are very grateful that you are considering the JW Marriott New Orleans for your conference. We look forward to making your stay memorable. Rufus Killarney, Booking Manager JW Marriott New Orleans |

Key Takeaway

Follow best practices when sharing information, requesting information or action, and replying to such messages.

Exercise

Choose a partner and email them a set of instructions following the message outline template and the example given in Table 6.1.3. It must be a procedure with at least five steps that is familiar to you (e.g., how to prepare your favorite drink) but unfamiliar to them. Can they follow your procedure and get the results you desire?

Reference

Stein, J. (2021, September 28). Yes, Sending an Email Can Create a Binding Contract. Forbes. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/joshuastein/2021/09/28/yes-sending-an-email-can-create-a-binding-contract/?sh=68de2b2950f2

6.2: Complaints and Claims

Section 6.2 Learning Objectives

- Plan, write, revise, and edit short documents and messages that are organized, complete, and tailored to specific audiences.

- Write routine message types such as information shares, requests, and replies.

Business doesn’t always go smoothly. Customers can be disappointed with a faulty product or poor service; shipments might get damaged en route, lost, or arrive late; or one business might infringe on their rights and freedoms. In all such cases, the offended party’s responsibility is to make the offending party aware of what went wrong and request a remedy. Indeed, it is their consumer right to do so, and the business or organization receiving such a message should take it as valuable information about customer expectations that must be met for the company to remain viable.

A claim explains what went wrong and demands compensation from the offending party, whereas a complaint explains what went wrong and merely demands correction or apology. Minor complaints are best communicated in person, on the phone, or by email (if it’s important to have them in writing) so they can be dealt with quickly. More serious complaints or claims are delivered as formal letters to provide a paper trail if they need to be used as evidence in a lawsuit.

Though some believe that a strongly worded complaint or claim is an effective way of getting what they want, you can catch more flies with honey than with vinegar (Michael, 2007, #3). In other words, if you are nice about communicating your problem with a situation or business transaction, the customer service representative (CSR) or manager dealing with it is more likely to give you what you want. Just because some customers have found success bullying people who are only trying to do their jobs, not all such attempts will likewise succeed, nor is it right from a moral standpoint, especially when the CSR had nothing to do with the complaint.

Ineffective complaints or claims often merely vent frustrations, issue threats, don’t state the desired remedy (or only vaguely imply it), or demand completely unreasonable compensation. Demanding a lifetime supply of milk from your grocery store because one carton happened to be rotten will result in nothing because the manager or CSR will dismiss it altogether as ridiculous opportunism. Threatening to shop elsewhere makes you sound like a lost cause and, therefore, not worth losing any more time or money over. Since such messages are usually aggressive (or passive-aggressive) in tone and consequently rude and offensive, the recipient may respond aggressively and give the complainant much less than what they asked for (e.g., a mere apology rather than compensation or replacement) or ignore the complaint altogether. Often the reader of such messages is not the one at fault, so a hostile message would be especially ineffective and possibly even actionable in extreme cases—i.e., liable to cause damages that the recipient could pursue compensation for in court.

Assume that a business will take your complaint or claim seriously if it is done right because, no matter what the industry, companies are rightly afraid of losing business to negative online reviews. According to one study, even one negative review can cost a business 22% of its customers and three negative reviews 59% of them (Arevalo, 2017). One mother’s endorsement or warning to others about a local store in a local mom’s group on Facebook could make or break that business. Even worse, complaints aired on social media, shared widely to the point of going viral, and picked up by news outlets, can destroy all but the too-big-to-fail companies or at least cause serious damage to their brand. In this digital age, good customer service is crucial to business survivability. A complaint provides a business with valuable information about customer expectations and an opportunity to win back a customer—as well as their social network if a good endorsement comes of it from the now-satisfied customer—or else risk losing much more than just the one customer.

Effective complaints or claims are politely worded and motivated by a desire to correct wrongs and save the business relationship. They’re best if they remind the business that you’ve been a loyal customer (if that’s true) and want to keep coming back, but you need them to prove that they value your business after whatever setback prompted the complaint. If the writer of such messages plays their cards right, they can get more than they originally bargained for.

Complaints and Claims Topics

- 6.2.1: Complaint or Claim Message Organization

- 6.2.2: Replies to Complaints or Claims

- 6.2.2.1: Apologizing

- 6.2.2.2: Social Media Response Flowchart

6.2.1: Complaint or Claim Message Organization

Complaints and claims take the direct approach of message organization even though they arise from dissatisfaction. They follow the usual three-part message organization we’ve seen before:

- Opening: To be effective at writing a complaint or claim, describe in the opening clearly, precisely, and politely what you would like to achieve with your message. If you want financial compensation or a replacement product in the case of a claim, be clear about the amount or model. You could also suggest equivalent or alternative compensation if it is unlikely that your request will be honored. If you want an error to be corrected or an apology in response to your complaint, be upfront about it.

- Body: The message body justifies the request by describing the desired outcome while chronologically stating what has happened and what went wrong. Be objective in recalling the facts because an angry tone coming through in negative words, accusations, and exaggerations will only undermine the validity of your complaint or claim. Be precise in such details as names, dates and times, locations (addresses), and product names and numbers. Wherever possible, provide and refer to evidence. For instance, you may include copies (definitely not originals) of documentation such as receipts, invoices, work orders, bills of lading, emails (printed), phone records, photographic evidence, and even video (e.g., of a damaged product).

- Closing: No matter what prompted the complaint or claim, the closing must be politely worded with action requests (e.g., a deadline) and goodwill statements. Impolite, rude, or even passive-aggressive wording will only invoke resilience in the reader, and your request will likely be rejected. By complimenting the recipient’s company, however, your chances of getting what you wanted and perhaps even something extra are much higher. In damage-control mode, the business wants you to feel compelled to tell your friends that the company turned it around.

Table 6.2.1: Outline for Complaints or Claims

| Outline | Content | Example Message |

|---|---|---|

| Subject Line | 3- to 7-word title | Refund for unwanted warranty purchase |

| 1) Opening | Main action request | Greetings:

Please refund me for the $89.99 extended warranty that was charged to my Visa despite being declined at the point of sale. |

| 2) Body | Narrative of events justifying the claim or complaint | This past Tuesday (June 12), I purchased an Acer laptop at the Belleville location of Future Shock Computers and was asked by the sales rep if I would like to add a 3-year extended warranty to the purchase. I declined and we proceeded with the sale, which included some other accessories. When I got home and reviewed the receipt (please find the PDF scan attached), I noticed the warranty that I had declined was added to the bill after all. |

| 3) Closing | Deadlines and/or submission details | Please refund the cost of the warranty to the Visa account associated with the purchase by the end of the week and let me know when you’ve done so. I have enjoyed shopping at Future Shock for the great prices and customer service. I would sincerely like to return to purchase a printer soon.

Much appreciated! Samantha |

Notice that the final point in the closing suggests to the store manager that they have an opportunity to continue the business relationship if all goes well with the correction.

6.2.2: Replies to Complaints or Claims

A message in which a company grants what the complainant or claimant has asked for is called an adjustment message. An adjustment letter or email is highly courteous in letting the disappointed customer know that they are valued and will be (or have already been) awarded what they were asking for, and possibly even more. Companies may use coupons for discounts on future purchases to win back the customer’s confidence, hoping that in return, the customer will tell their friends that the store or company is worthy of their business after all. An adjustment message takes the direct approach by immediately delivering the good news about granting the claimant’s request. Though you would probably start with an apology if this situation arose in person, starting on a purely positive note is more effective in a written message. The tone of the message is fundamental, as is avoiding blaming the customer—even if they’re partly to blame or if part of you still suspects that the claim is not entirely valid. If you will grant the claim, write it whole-heartedly, providing good customer service on behalf of your company.

Though a routine adjustment letter might skip a message body, a more serious one may need to detail how you are complying with the request or take the time to explain what your company is doing to prevent the error again. Doing this makes the reader feel as though making an effort to write will have made a positive impact in the world, however small, because it will benefit not only you but also everyone else who won’t have to go through what you did. Even if you have to explain how the customer can avoid this situation in the future (e.g., by using the product or service as it was intended), putting the responsibility partly on their shoulders, do so in entirely positive terms. An apology might also be appropriate in the message body (see §6.2.2.1 below).

Table 6.2.2: Outline for Complaints or Claims

| Outline | Content | Example Message |

|---|---|---|

| Subject Line | Identify the previous subject line | Re: Refund for unwanted warranty purchase |

| 1) Opening | Main point about granting the request | Hello, Samantha:

Absolutely, we would be happy to refund you for the $90 warranty mistakenly charged along with your purchase of the Acer laptop. For your inconvenience, we will also offer you a $20 gift card for future purchases at our store. |

| 2) Body | Details of compliance and/or assurances of improved process | To receive your refund and gift card, please return to our Belleville location with your receipt and the credit card you purchased the computer with so that we can credit the same card $90. (For consumer protection reasons, we are unable to complete any transactions without the card.)

We are sorry for inconveniencing you and will speak with all sales staff about the importance of carefully checking the accuracy of any bill of sale before sending the order for payment. To ensure that this doesn’t happen again, we will also instruct sales staff to confirm with customers whether an extended warranty appearing on the sales bill is there with consent before completing any transaction. |

| 3) Closing | Courteous statements expressing confidence in future business relations | We appreciate your choosing Future Shock for your personal electronics and look forward to seeing you soon to credit your Visa card and provide you with the best deal in town on the printer you were looking to purchase.

Have a great day! Melissa |

When a claim or complaint does not warrant an adjustment and such rejection must be communicated to the customer, a compelling negative message must be written, as described in section 6.3.2.

6.2.2.1: Apologizing

Most customers welcome or even expect an apology to win back their confidence in the company and to continue to do business with them. The problem arises when such apologies create a cause of action in legal proceedings when the company implies admitting the wrongdoing by simply apologizing to the customer. Courts had viewed such apologies as admitting misconduct, especially when it involved injury or damage to property. For this reason, it is essential to consult with a manager or the company’s legal department before apologizing to a customer or other stakeholders in writing.

Legal repercussions are not expected if apologizing for a minor mistake, such as sending the wrong color dress in the order. It is certainly something a customer service representative should do to appease an upset customer. Such an apology should be sincere, responsible, specific, and improvement-focused. “Sorry for your inconvenience” is just a trite phrase that may only anger the customer even more. A more specific and sincere apology should be provided instead: “We are sincerely sorry for providing the dress in the incorrect color” sounds more honest. If approved by legal counsel or your manager, the mistake should be admitted and full responsibility should be taken for it instead of trying to come up with excuses or blaming others. A sincere apology is also specific, providing identifiable details and persons responsible for the action. Most importantly, to regain the customer’s confidence and future business, it is imperative to provide information about how the company will ensure that such mishaps will not happen again.

Apologizing may be necessary when you are not really in the wrong, but the customer’s or public’s perception is that you are. In crisis communications, effective apologies show that you care enough about your existing and potential customers to say and do what it takes to win back their trust and confidence in you. You can do this without falsely claiming that you made an error (if you genuinely didn’t) by saying that you apologize for the misunderstanding. Dismissing complaints and doubling down on a mistake, on the other hand, shows disrespect for the people your success depends on.

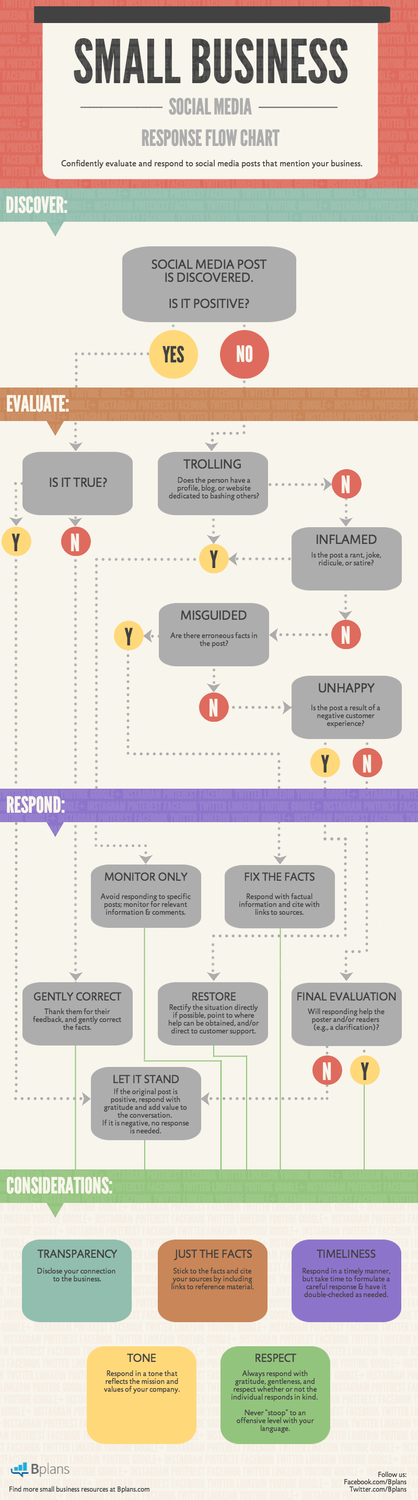

6.2.2.2: Social Media Response Flowchart

Business entities often provide their customer representative with a flowchart describing how to properly respond to social media posts that mention the company. Please see the example below. (Source: How to Choose Which Social Media Platforms Are Right for Your Business)

Key Takeaway

When something goes wrong in a commercial situation, courteous communication is essential when both asking for and responding to complaints and claims.

Exercises

- If you’ve ever felt mistreated or taken advantage of in a business transaction but did nothing about it, write a complaint or claim letter asking that the company correct the wrong following the guidance in §8.2.1 above. You don’t need to actually send it, but do so if you feel strongly about it and feel as though you have a reasonable chance at success.

- Put yourself in the shoes of the company that you wrote to in the previous exercise. Write a response to your message following the advice in §8.2.2 above.

References

Arevalo, M. (2017, March 15). The impact of online reviews on businesses. BrightLocal. Retrieved from https://www.brightlocal.com/2017/03/15/the-impact-of-online-reviews/

Michael, P. (2007, January 28). How to complain and get a good result. Wise Bread. Retrieved from http://www.wisebread.com/how-to-complain-and-get-a-good-result

6.3: Negative Messages

Section 6.3 Learning Objective

1. Organize and write negative messages.

Just as in life, the workplace isn’t always sunny. Sometimes things don’t go according to plan. It is your job to communicate negative aspects that don’t ruin your relationships with customers, coworkers, managers, the public, or any other stakeholders. Bad-news or so-called negative messages require care and skillful language because your main point will likely meet with resistance. People will generally have a negative reaction when told that they’re laid off, their application has been rejected, their shipment got lost on the way, prices or rates are increasing, their appointment has to be moved back several months, or they’re losing their benefits. Although some people may prefer to receive bad news directly, in most cases, you can assume that the receiver will appreciate or even benefit from a more tactful, indirect approach. Keep in mind the following advice whenever required to deliver unwelcome news.

Negative Messages Topics

- 6.3.1: The Seven Goals of Negative Messages

- 6.3.2: Indirect Approach to Negative Messages

- 6.3.2.1: Negative Message Buffer

- 6.3.2.2: Justification of Negative Messages

- 6.3.2.3: Negative Messages and Redirection

- 6.3.3: Mitigating Negative Messages

- 6.3.3.1: Avoid Negative or Abusive Language

- 6.3.3.2: Avoid Oversharing but Tell the Truth

- 6.3.3.3: Respect the Recipient’s Privacy

- 6.3.4: Crisis Communication

- 6.3.5: Direct Approach Bad-news Messages

- 6.3.6: Examples of Closing Paragraphs

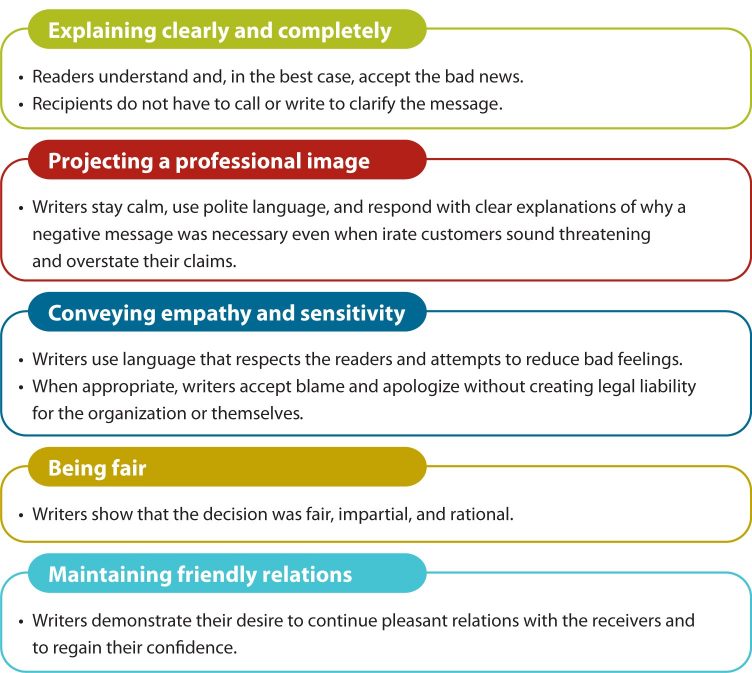

6.3.1: The Seven Goals of Bad-news Messages

Your ability to manage, clarify, and guide the understanding of the recipient of your message is key to addressing challenging situations while maintaining trust and integrity with customers, coworkers, managers, the public, and other stakeholders. Keep in mind these seven goals when delivering bad news in person or in writing:

- Negative messages should be clear and concise and provide all important facts and information

- Provide the recipient with information to understand and accept that bad news.

- Express sympathy and empathy to reduce the anxiety caused by negative news.

- Retain the customer’s confidence and future business by respectful and trustworthy communication.

- Use appropriate channels and timing for delivering the bad news.

- Check with a supervisor to avoid legal liability by admitting negligence or guilt.

- Ensure the desired business outcome.

The following example is a workplace situation where you as a supervisor must mitigate an issue when an employee has been consistently arriving late to work. The individual’s actions negatively impact the entire team, and your task is to speak to the employee about this situation.

At first, it may seem like you have several options:

- Speak to the employee at the workplace by simply stating that if they don’t start coming to work on time, their employment will be terminated.

- Invite the employee to an upscale restaurant for lunch and explain the situation.

- Write a stern email.

- Speak with the employee in the privacy of your office.

Only the last alternative meets the seven goals in delivering negative messages, but we will discuss why the other options are less than desirable in this situation.

Discussing personnel matters in front of other employees is not only tactless, but it may also cause liability issues. Confronting an employee with a short blunt statement does not provide additional information and is likely to prompt a hostile response. It is human nature to become defensive when accused of wrongdoing, especially if done in front of others.

Inviting the employee to a restaurant can provide opposing verbal communication clues than what is truly intended, which may lead to misunderstanding and worsening of the situation. Employees are typically invited to upscale lunches to celebrate a promotion or a similar accomplishment, but certainly not when discussing one’s tardiness and possible termination of employment.

From a legal liability standpoint, writing an email will dispense written evidence of what has been said on your part, which could be used in a possible wrongful termination dispute. Since the employee’s immediate reaction will not be visible while reading your email, this is certainly not the best channel to discuss such a sensitive issue. Also, you may accidentally send emails to unintended recipients, and they can also be forwarded by a disgruntled employee, potentially causing more liability problems.

Beginning the private meeting with a sympathetic statement that you have been worried about the employee’s work lately and asking whether everything is okay is a much better way to begin your investigation into the matter. The employee may respond by providing a plausible explanation right away or you may have to offer specific work-related mistakes that the employee has made to prompt an acknowledgment. From your tone of voice, the employee should feel that you are genuinely concerned and not authoritatively demanding (although you may have all the right to do so). Finding a replacement for an otherwise valuable employee is much less cost-effective than keeping an existing one.

One additional point to consider as you document this interaction is the need to present the warning in writing. You may elect to prepare a memo that outlines the information concerning the employee’s performance and tardiness and have it ready should you want to present it. If the session goes well, and you have the discretion to make a judgment call, you may elect to give him another week to resolve the issue. Even if it goes well, you may want to present the memo, as it documents the interaction and serves as evidence of due process should the employee’s behavior fail to change, eventually resulting in the need for termination. This combined approach of a verbal and written message is increasingly the norm in business communication (Business Communication for Success, 2015, 17.1).

6.3.2: Indirect Approach to Negative Messages

The indirect approach should be used when delivering negative messages in situations when the news may be upsetting to the recipient, may provoke a hostile reaction, could threaten the relationship with a customer, or when the negative information is unexpected:

Suppose you bluntly state the really bad news. In that case, you risk the recipient rejecting or misunderstanding it because they may be too distracted with anger or sadness to rationally process the explanation or instructions for what to do about the bad news. The key to avoiding misunderstandings when delivering bad news is to follow the four-part organization of negative messages:

- Buffer

- Justification

- Bad news + redirection

- Positive action closing

This is much like the three-part structure we’ve seen before. Only the body is now divided into two distinct parts where the order matters, as we see in Table 6.3.2 and the explanation for each part below it.

Table 6.3.2: Bad-news Message Outline and Example Message

| Part | Example Message |

|---|---|

| 1. Buffer | Thank you for your order. We appreciate your interest in our product and are confident you will love it. |

| 2. Explanation | We are writing to let you know that this product has been unexpectedly popular with over 10,000 orders submitted on the day you placed yours. |

| 3. Bad news + redirect | This unexpected increase in demand has resulted in a temporary out-of-stock/backorder situation. Despite a delay of 2–3 weeks, we will definitely fulfill your order as it was received at 11:57 p.m. on October 9, 2018, as well as gift you a $5 coupon toward your next purchase. |

| 4. Positive action closing | While you wait for your product to ship, we encourage you to use the enclosed $5 coupon toward the purchase of any product in our online catalog. We appreciate your continued business and want you to know that our highest priority is your satisfaction. |

(Business Communication for Success, 2015, 17.1)

6.3.2.1: Negative Message Buffer

Begin with neutral or positive statements that set a welcoming tone and serve as a buffer for the information to come. A buffer softens the blow of bad news like the airbag in a car softens the driver’s collision with the steering wheel in a high-speed car accident. If any silver linings can calm the poor person about to be battered by the dark thunder clouds of bad news, here at the beginning would be a good time to point them out. The following are some possible buffer strategies:

- Good news: If there’s good news and bad news, start with the good news.

- Compliment: If you’re rejecting someone’s application, start by complimenting them on their efforts and other specific accomplishments you were impressed by in their application.

- Gratitude: Say thanks for whatever positive things the recipient has done in your dealings with them. If they’ve submitted a claim that doesn’t qualify for an adjustment, thank them for choosing your company.

- Agreement: Before delivering bad news that you’re sure the recipient will disagree with and oppose, start with something you’re sure you both agree on. Start on common ground by saying, “We can all agree that . . . ”

- Facts: If positives are hard to come by in a situation, getting started on the next section’s explanation, starting with cold, hard facts, is the next best thing.

- Understanding: Again, if there are no silver linings to point to, showing you care by expressing sympathy and understanding is a possible alternative (Guffey et al. 2016, p. 194).

- Apology: If you’re at fault for any aspect of a bad-news message, an apology is appropriate as long as it won’t leave you at a disadvantage in legal proceedings that may follow as a result of admitting wrongdoing. (See §6.2.2.1 above for more on effective strategies for apologizing.)

The idea here is not to fool the audience into thinking that only good news is coming but putting them in a receptive frame of mind to understand the following explanation. If you raise the readers’ expectation that they’re going to hear only the good news they want, just to let them down near the end, they will be even more disappointed for being misled. Suppose you bluntly blast the bad news right away, however. In that case, they may be more distracted by emotion to rationally process the explanation or instructions for what to do about the bad news.

6.3.2.2: Justification of Negative Messages

The justification section of negative messages explains the background or context for the bad news before delivering the bad news itself. Let’s say that you must reject an application, claim for a refund, or request for information. In such cases, the explanation could describe the strict acceptance criteria and high quality of applications received in the competition, the company policy on refunds, its policy on allowable disclosures, and the legalities of contractually obligated confidentiality. Your goal with the explanation is to be convincing so that the reader says, “That sounds reasonable,” and similarly accepts the bad news as inevitable given the situation you describe. On the other hand, if you make the bad news seem like mysterious and arbitrary decision-making, your audience will probably feel like they’ve been treated unfairly and might even escalate further with legal action or “yelptribution”—avenging the wrong on social media. While an explanation is ethically necessary, never admit or imply responsibility without written authorization from your company, cleared by legal counsel if there’s any way that the justification might be seen as actionable (i.e., the offended party can sue for damages). Use additional strategies to make the justification more agreeable, such as focusing on benefits. If you’re informing employees that they will have to pay double for parking passes next year in an attempt to reduce the number of cars filling up the parking lot, you could sell the idea on the health benefits of cycling to work or the environmental benefit of fewer cars polluting the atmosphere. If you’re informing a customer asking why a product or service can’t include additional features, you could say that adding those features would drive the cost up, and you would rather respect your customer’s pocketbooks by keeping the product or service more affordable. In any case, try to pitch an agreeable benefit rather than saying that you’re merely trying to maximize company or shareholder profits.

6.3.2.3: Negative Messages and Redirection

Burying the bad news itself in the message is a defining characteristic of the indirect approach. Far from intending to hide the bad news, the indirect approach frames the bad news so that it can be properly understood and its negative (depressing or anger-arousing) impact minimized.

The goal is also to be clear in expressing the bad news so that it isn’t misunderstood while also being sensitive to your reader’s feelings. If you’re rejecting a job applicant, you can be clear that they didn’t get the job without bluntly saying, “You failed to meet our criteria” or “You won’t be working for us anytime soon.” Instead, you can imply it by putting the bad news in a subordinate clause in the passive voice:

- Though another candidate was hired for the position, . . .

The passive voice enables you to draw attention away from your own role in rejecting the applicant and away from the rejected applicant in the context of the competition itself. Instead, you focus on the positives of someone getting hired. While the rejected applicant probably won’t be throwing a celebration party for the winning candidate, the subordinate clause here allows for speedy redirection to a consolation prize.

Redirection is key to this type of bad news’ effectiveness because it quickly shifts the reader’s attention to a plausible alternative to their original request. Offering a coupon or store credit, if available, will make accepting the bad news or rejection easier and will be appreciated as being better than nothing. Even if you’re not able to offer the reader anything of value, you could at least say something nice. In that case, completing the sentence in the previous paragraph with an active-voice main clause could go as follows:

- . . . we wish you success in your continued search for employment.

This way, you avoid saying anything negative while still clearly rejecting the applicant.

6.3.3: Mitigating Negative Messages

Delivering bad news can be dangerous if it angers the reader so much that they are motivated to seek revenge. If you’re not careful with what you say, that message can be used as evidence in a court case and could compromise your position when read by a judge or jury. You can lower the risk of being litigated by following the general principles given below when delivering bad news.

6.3.3.1: Avoid Negative or Abusive Language

Sarcasm, profanity, harsh accusations, and abusive or insulting language may feel good to write in a fit of anger but, in the end, make everyone’s lives more difficult. When someone sends an inflammatory message and the reader interprets it as harmful to their reputation, it could legally qualify as libel that is legitimately actionable. Even if you write critically about a rival company’s product or service by stating (as if factually) that it’s dangerous, whereas your version of the product or service is safer and better, this can be considered defamation or libel. If said aloud and recorded, perhaps on a smartphone’s voice recorder, it is slander and can likewise be litigated. It’s much better to always write courteously and maturely, even under challenging circumstances, to avoid the fallout that involves expensive court proceedings.

6.3.3.2: Avoid Oversharing but Tell the Truth

When your job is to provide a convincing rationale that might make the recipient of bad news accept it as reasonable, be careful with what details you disclose. When rejecting a job applicant, for instance, you must be especially careful not to lay all your cards on the table by sharing the winning and rejected candidates’ scoring sheets, nor even summarizing them. Though that would give them a full picture, it would open you up to a flood of complaints and legal or human-rights challenges picking apart every little note. Instead, you would simply wish the rejected candidate luck in their ongoing job search. When you must provide detail, avoid saying anything negative about anyone so that you can’t be accused of libel and taken to court for it. Provide only as much information as is necessary to provide a convincing rationale.

At the same time, you must tell the truth so that you cannot be challenged on the details. If you are inconsistent or contradictory in your explanation, it may invite scrutiny and accusations of lying. Even making false claims by exaggerating may give the reader the wrong impression, leading to serious consequences. Although avoiding providing some facts may appear as dishonest, you must protect your organization and avoid triggering hostile behavior from the recipient.

6.3.3.3: Respect the Recipient’s Privacy

Criticizing an employee in a group email or memo—even if the criticism is fair—is mean, unprofessional, and an excellent way of opening yourself to a world of trouble. People who call out others in front of a group create a chilly climate in the workplace, leading to fear, loathing, and a loss of productivity among employees, not to mention legal challenges for possible libel. Called-out employees may even resort to sabotaging the office with misbehavior such as vandalism, cyberattacks, or theft to get even. Always maintain respect and privacy when communicating bad news as a matter of proper professionalism (Business Communication for Success, 2015, 17.1).

6.3.4: Crisis Communications

A rumor that the CEO is ill pulls down the stock price. A plant explosion harms several workers and requires evacuating residents in several surrounding city blocks. Risk management seeks to address such risks, including prevention as well as liability, but emergency and crisis situations happen anyway. Employees also make errors in judgment that can damage the public perception of a company. The mainstream media does not lack stories involving addiction or abuse that require a clear response from a company’s standpoint. It is crucial to respond to such negative information even if it brings unwanted attention to the company because, with active engagement, the company can control the narrative that appears in the media. If the storytelling is left to the press, factual information may be distorted or sensationalized, and the corporation may not have any venues to safeguard what is being reported. In this chapter, we address the basics of a crisis communication plan, focusing on critical types of information during an emergency:

- What is happening?

- Is anyone in danger?

- How big is the problem?

- Who reported the problem?

- Where is the problem?

- Has a response started?

- What resources are on-scene?

- Who is responding so far?

- Is everyone’s location known? (Mallet, Vaught, & Brinch, 1999)

You will be receiving information from the moment you know a crisis has occurred. Still, without a framework or communication plan to guide you, valuable information may be ignored or lost. These questions help you quickly focus on the basics of “who, what, and where” in the crisis.

A crisis communication plan is the prepared scenario document that organizes information into responsibilities and lines of communication before an event. If an emergency arises when you already have a plan, each person knows their role and responsibilities from a common reference document. Overall effectiveness can be enhanced with a clear understanding of roles and responsibilities for an effective and swift response. The plan should include four elements:

- Crisis communication team members with contact information

- Designated spokesperson

- Meeting place/location

- Media plan with procedures

A crisis communication team includes people who can decide what actions to take, carry out those actions, and offer expertise or education in the relevant areas. By designating a spokesperson prior to an actual emergency, your team addresses the inevitable need for information proactively. People will want to know what happened and where to get further details about the crisis. Lack of information breeds rumors that can make a bad situation worse. The designated spokesperson should be knowledgeable about the organization and its values; be comfortable in front of a microphone, camera, and media lights; and stay calm under pressure. Part of your communication crisis plan should focus on where you will meet to coordinate and communicate your activities in response to the crisis. In case of a fire in your house, you might meet in the front yard. In an organization, a designated contingency building or office some distance away from your usual place of business might serve as a central place for communication in an emergency that requires evacuating your building. Depending on the size of your organization and its facilities, the emergency plan may include exit routes, hazardous materials procedures (OSHA), and policies for handling bomb threats, for example. Safety is, of course, the priority, but in terms of communication, the goal is to eliminate confusion about where people are, where they need to be, and where information is coming from. Whether or not evacuation is necessary when a crisis occurs, your designated spokesperson will gather information and carry out your media plan. They will need to make quick judgments about which information to share, how to phrase it, and whether certain individuals need to be notified of facts before they become public. The media and public will want to get reliable information, which is preferable to mere spin or speculation. Official responses help clarify the situation for the public, but an unofficial interview can make the tragedy personal and attract unwanted attention. Remind employees to direct all inquiries to the official spokesperson and never to speak anonymously or “off the record.” Enable your spokesperson to have access to the place you indicated as your crisis contingency location to coordinate communication and activities and allow them to prepare and respond to inquiries. When crisis communication is handled professionally, it seeks not to withhold information or mislead but to minimize the “spin damage” from the incident by providing necessary facts even if they are unpleasant or tragic (Business Communication for Success, 2015, 17.3).

6.3.5: Direct Approach in Negative Messages

We’ve looked at expressing negative news using the indirect approach, which is most often used, but there are situations when it is better to use the direct approach and put the reader on notice right away. In the following situations, it is certainly appropriate to deliver bad news by getting right to the point:

- When the bad news isn’t that bad:

- In the case of small price or rate increases, customers won’t be devastated by having to pay more. Indeed, inflation makes such increases an expected fact of life.

- If your job involves routinely delivering criticism because you’re a Quality Assurance specialist, the people who are used to receiving recommendations to improve their work will appreciate the direct approach. Some organizations even require direct-approach communications for bad news as a policy because it is more time-efficient.

- When you know that the recipient prefers or requires the direct approach: Though the indirect approach is intended as a nice way to deliver negative news, some people would rather you be blunt. Since a message must always be tailored to the audience, getting permission to take the direct approach is your cue to follow through with precisely that. Not doing so may trigger the angry response you would have expected otherwise.

- When you’re short on time or space: One of the hallmarks of the indirect approach is that it takes more words than a direct-approach message (see Table 6.1.5 for comparative examples). If time is limited or you’re constrained in how much space you have to write, taking the direct approach is justifiable.

- When the indirect approach hasn’t worked: If this is the third time you’ve had to tell a client to pay their invoice and the first two were nicely worded indirect messages that the recipient ignored, take the kid gloves off and issue a stern warning of the consequences of not paying. You may need to threaten legal action or say you’ll refer the account to a collection agency, and you may need to put it in bold so that you’re sure the reader won’t miss it.

- When the reader may miss the bad news: You may determine from profiling your audience and their literacy level that they might not understand indirect-approach bad news. If your reader doesn’t have a strong command of English vocabulary and misses words here and there, they may not pick up on the buried bad news past the mid-point of a challenging message.

In the above situations, structure your message following the same three-part organization we’ve seen elsewhere (e.g., §6.1.5–§6.1.7 on email parts):

- Opening: State the bad news right upfront.

- Body: Briefly explain why the bad news happened.

- Closing: Express confidence in continued business relations with a goodwill statement and provide any action information such as contact instructions should the recipient require further information.

Of course, clarity and brevity in such messages are vital to maintaining friendly relations with your audiences (Guffey et al., 2016, p. 190).

6.3.6: Examples of Closing Paragraphs

- Thanks for your bid. We may be able to work with your talented staff when future projects demand your unique expertise.

- Although the lot you saw last week is now sold, we do have two excellent lots available at a slightly higher price.

- We appreciate your interest in our company, and we extend to you our best wishes in your search to find the perfect match between your skills and job requirements.

- Your loyalty and concern about our frozen meals are genuinely appreciated. Because we want you to continue enjoying our healthy and convenient dinners, we are enclosing a coupon for your next nutritious Town Foods meal that you can redeem at your local market. (Guffey et al., 2022, p. 295)

Key Takeaway

Write carefully when addressing negative situations, such as delivering bad news, usually by burying the bad news after a buffer and rationale, and following it with redirection to minimize the harm that the message might cause.

Exercises

- Think of a time when you were given bad news by email or letter, such as when you were told that a warranty couldn’t be honored for the type of damage inflicted on your product or your application was rejected. How well did it fulfill or fail to fulfill the seven goals of delivering bad news (see §6.3.1 and §6.3.3)?

- Sales have decreased for two consecutive quarters at your business. You must inform your sales team that their hours and base pay will be reduced by 20% if the company is to break even this quarter. While you may have a few members of your sales team that are underperforming, you can’t afford to be short-staffed now, so you must keep the entire team for the time being. Write negative news messages in both the direct and indirect approach informing your sales team of the news following the advice in §6.3.2 and §6.3.5 above.

- Research a crisis in your area of training or career field. What communication issues were present and how did they affect the response to the crisis? If the situation was handled well, what are the major takeaways? If handled poorly, what do you think you would have done differently following the general guidelines in §6.3.4 above?

References

Guffey, M. E., Loewy, D., Almonte, R. (2016). Essentials of business communication (8th Can. Ed.). Toronto: Nelson.

Lehman, C. M., DuFrene, D, & Murphy, R. (2013). BCOM (1st Can. Ed.). Toronto: Nelson Education.

Mallet, L., Vaught, C., & Brinch, M. (1999). The emergency communication triangle. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Pittsburgh, PA: Pittsburgh Research Laboratory.