9 1: Concepts of Corrections as a Sub-system of the Criminal Justice System

Key Terms:

Walnut Street Jail Specific Deterrence Rehabilitation Recidivism Criminogenic Needs

Pennsylvania System General Deterrence Retribution

Mandatory Minimum Sentences Evidence-based Practices

Deterrence Incapacitation Bigotry

Three-Strikes Law Risk Assessments

- : History and Philosophy

- : Deterrence

- : Incapacitation

- : Rehabilitation

- : Retribution

- : A Racist System?

- : Prison Overcrowding

- : States Shifting Focus from Incarceration to Rehabilitation

This page titled 1: Concepts of Corrections as a Sub-system of the Criminal Justice System is shared under a CC BY 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by Dave Wymore & Tabitha Raber.

: History and Philosophy

Prior to the 1800s, common law countries relied heavily on physical punishments. Influenced by the high ideas of the enlightenment, reformers began to move the criminal justice system away from physical punishments in favor of reforming offenders. This was a dramatic shift away from the mere infliction of pain that had prevailed for centuries. Among these early reformers was John Howard, who advocated the use of penitentiaries. Penitentiaries, as the name suggests, were places for offenders to be penitent. That is, they would engage in work and reflection on their misdeeds. To achieve the appropriate atmosphere for penitence, prisoners were kept in solitary cells with much time for reflection.

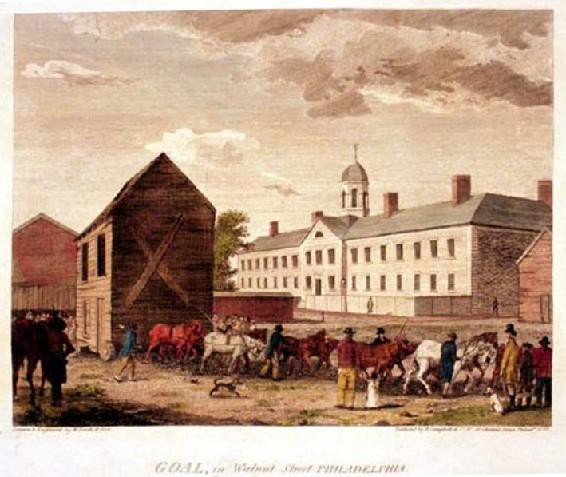

Philadelphia’s Walnut Street Jail was an early effort to model the European penitentiaries. The system used there later became known as the Pennsylvania System. Under this system, inmates were kept in solitary confinement in small, dark cells. A key element of the Pennsylvania System is that no communications whatsoever were allowed. Critics of this system began to speak out against the practice of solitary confinement early on. They maintained that the isolated conditions were emotionally damaging to inmates, causing severe distress and even mental breakdowns. Nevertheless, prisons across the United States began adopting the Pennsylvania model, espousing the value of rehabilitation.

|

Figure 1.1 Walnut Street Prison, Pennsylvania Historical Marker, on southeast corner of 6th and Walnut Streets. Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International |

Figure 1.2 “Jail in Walnut Street, Philadelphia.” Plate 24 from W. Birch & Son. Public Domain. |

The New York system evolved along similar lines, starting with the opening of New York’s Auburn Penitentiary in 1819. This facility used what came to be known as the congregate system. Under this system, inmates spent their nights in individual cells, but were required to congregate in workshops during the day. Work was serious business, and inmates were not allowed to talk while on the job or at meals. This emphasis on labor has been associated with the values that accompanied the Industrial Revolution. By the middle of the nineteenth century, prospects for the penitentiary movement were grim. No evidence had been mustered to suggest that penitentiaries had any real impact on rehabilitation and recidivism.

Prisons in the South and West were quite different from those in the Northeast. In the Deep South, the lease system developed. Under the lease system, businesses negotiated with the state to exchange convict labor for the care of the inmates. Prisoners were primarily used for hard, manual labor, such as logging, cotton picking, and railroad construction. Eastern ideas of penology did not catch on in the West, with the exception of California. Prior to statehood, many frontier prisoners were held in federal military prisons.

Figure 1.3 Convict Lease. Public Domain

Disillusionment with the penitentiary idea, combined with overcrowding and understaffing, led to deplorable prison conditions across the country by the middle of the nineteenth century. New York’s Sing Sing Prison was a noteworthy example of the brutality and corruption of that time. A new wave of reform achieved momentum in 1870 after a meeting of the National Prison Association (which would later become the American Correctional Association). At this meeting held in Cincinnati, members issued a Declaration of Principles. This document expressed the idea that prisons should be operated according to a philosophy that prisoners should be reformed, and that reform should be rewarded with release from confinement. This ushered in what has been called the Reformatory Movement.

One of the earliest prisons to adopt this philosophy was the Elmira Reformatory, which was opened in 1876 under the leadership of Zebulon Brockway. Brockway ran the reformatory in accordance with the idea that education was the key to inmate reform. Clear rules were articulated, and inmates that followed those rules were classified at higher levels of privilege. Under this “mark” system, prisoners earned marks (credits) toward release. The number of marks that an inmate was required to earn in order to be released was established according to the seriousness of the offense. This was a movement away from the doctrine of proportionality, and toward indeterminate sentences and community corrections.

The next major wave of corrections reform was known as the rehabilitation model, which achieved momentum during the 1930s. This era was marked by public favor with psychology and other social and behavioral sciences. Ideas of punishment gave way to ideas of treatment, and optimistic reformers began attempts to rectify social and intellectual deficiencies that were the proximate causes of criminal activity. This was essentially a medical model in which criminality was a sort of disease that could be cured. This model held sway until the 1970s when rising crime rates and a changing prison population undermined public confidence.

After the belief that “nothing works” became popular, the crime control model became the dominate paradigm of corrections in the United States. The model attacked the rehabilitative model as being “soft on crime.” “Get tough” policies became the norm throughout the 1980s and 1990s, and lengthy prison sentences became common. The aftermath of this has been a dramatic increase in prison populations and a corresponding increase in corrections expenditures. Those expenditures have reached the point that many states can no longer sustain their departments of correction. The pendulum seems to be swinging back toward a rehabilitative model, with an emphasis on community corrections. While the community model has existed parallel to the crime control model for many years, it seems to be growing in prominence.

When it comes to criminal sanctions philosophy, what people believe to be appropriate is largely determined by the theory of punishment to which they subscribe. That is, people tend to agree with the theory of punishment that is most likely to generate the outcome they believe is the correct one. This system of beliefs about the purposes of punishment often spills over into the political arena. Politics and correctional policy are intricately related. Many of the changes seen in corrections policy in the United States during this time were a reflection of the political climate of the day. During the more liberal times of the 1960s and 1970s, criminal sentences were largely the domain of the judicial and executive branches of government. The role of the legislatures during this period was to design sentencing laws with rehabilitation as the primary goal. During the politically conservative era of the 1980s and 1990s, lawmakers took much of that power away from the judicial and executive branches. Much of the political rhetoric of this time was about “getting tough on crime.” The correctional goals of retribution, incapacitation, and deterrence became dominate, and rehabilitation was shifted to a distant position.

- : History and Philosophy is shared under a CC BY 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by LibreTexts.

: Deterrence

It has been a popular notion throughout the ages that fear of punishment can reduce or eliminate undesirable behavior. This notion has always been popular among criminal justice thinkers. These ideas have been formalized in several different ways. The Utilitarian philosopher Jeremy Bentham is credited with articulating the three elements that must be present if deterrence is to work: The punishment must be administered with celerity, certainty, and appropriate severity. These elements are applied under a type rational choice theory. Rational choice theory is the simple idea that people think about committing a crime before they do it. If the rewards of the crime outweigh the punishment, then they do the prohibited act. If the punishment is seen as outweighing the rewards, then they do not do it. Sometimes criminologists borrow the phrase cost-benefit analysis from economists to describe this sort of decision-making process.

When evaluating whether deterrence works or not, it is important to differentiate between general deterrence and specific deterrence. General deterrence is the idea that every person punished by the law serves as an example to others contemplating the same unlawful act. Specific deterrence is the idea that the individuals punished by the law will not commit their crimes again because they “learned a lesson.”

Critics of deterrence theory point to high recidivism rates as proof that the theory does not work. Recidivism means a relapse into crime. In other words, those who are punished by the criminal justice system tend to reoffend at a very high rate. Some critics also argue that rational choice theory does not work. They argue that such things as crimes of passion and crimes committed by those under the influence of drugs and alcohol are not the product of a rational cost-benefit analysis.

As unpopular as rational choice theories may be with particular schools of modern academic criminology, they are critically important to understanding how the criminal justice system works. This is because nearly the entire criminal justice system is based on rational choice theory. The idea that people commit crimes because they decide to do so is the very foundation of criminal law in the United States. In fact, the intent element must be proven beyond a reasonable doubt in almost every felony known to American criminal law before a conviction can be secured. Without a culpable mental state, there is no crime (with very few exceptions).

- : Deterrence is shared under a CC BY 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by LibreTexts.

: Incapacitation

Incapacitation is a very pragmatic goal of criminal justice. The idea is that if criminals are locked up in a secure environment, they cannot go around victimizing everyday citizens. The weakness of incapacitation is that it works only as long as the offender is locked up. There is no real question that incapacitation reduces crime by some degree. The biggest problems with incapacitation is the cost. There are high social and moral costs when the criminal justice system takes people out of their homes, away from their families, and out of the workforce and lock them up for a protracted period. In addition, there are very heavy financial costs with this model. Very long prison sentences result in very large prison populations which require a very large prison industrial complex. These expenses have placed a crippling financial burden on many states.

- : Incapacitation is shared under a CC BY 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by LibreTexts.

: Rehabilitation

Overall, rehabilitation efforts have had poor results when measured by looking at recidivism rates. Those that the criminal justice system tried to help tend to reoffend at about the same rate as those who serve prison time without any kind of treatment. Advocates of rehabilitation point out that past efforts failed because they were underfunded, ill-conceived, or poorly executed.

There has been a significant trend among prisons today to return to the rehabilitative model. However, this new effort has been guided by “evidence-based” treatment models which requires treatment providers to demonstrate their programs offer significant improvement in recidivism rates. This movement begins during incarceration with programs designed to address specific needs of the offenders. As the offender gets closer to his release date, the focus shifts to reintegrating him or her into society. Prison case managers work with the offender to locate resources available to the offender in the community, work on relationships with families and develop employment opportunities in order for the offender to be a productive member of society. Upon release, the offender often receives support from their probation or parole officer who provides supervision, treatment resources, and employment information.

- : Rehabilitation is shared under a CC BY 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by LibreTexts.

: Retribution

Retribution means giving offenders the punishment they deserve. Most adherents to this idea believe that the punishment should fit the offense. This idea is known as the doctrine of proportionality. Such a doctrine was advocated by early Italian criminologist Cesare Beccaria who viewed the harsh punishments of his day as being disproportionate to many of the crimes committed. The term just desert is often used to describe a deserved punishment that is proportionate to the crime committed.

In reality, the doctrine of proportionality is difficult to achieve. There is no way that the various legislatures can go about objectively measuring criminal culpability. The process is one of legislative consensus and is imprecise at best.

- : Retribution is shared under a CC BY 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by LibreTexts.

: A Racist System?

The United States today can be described as both multiracial and multiethnic. This has led to racism. Racism is the belief that members of one race are inferior to members of another race. Because white Americans of European heritage are the majority, racism in America usually takes on the character of whites against racial and ethnic minorities. Historically, these ethnic minorities have not been given equal footing on such important aspects of life as employment, housing, education, healthcare, and criminal justice. When this unequal treatment is willful, it can be referred to as racial discrimination. The law forbids racial discrimination in the criminal justice system, just as it does in the workplace.

Bigotry is not present in every facet of the criminal and juvenile justice systems, but there are possible incidents of prejudice within both systems. Discrimination has taken place in such areas as criminal sentencing, use of force by police, and the imposition of the death penalty. One topic of recent discussion is a disparity in federal drug policy. While much has recently changed with the passage of the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010, federal drug law was a prime example of disproportion impacts on minority populations.

Courts are not immune to cries of racism from individuals and politically active groups. The American Civil Liberties Union (2014), for example, states, “African-Americans are incarcerated for drug offenses at a rate that is 10 times greater than that of whites.” The literature on disproportionate minority sentencing distinguishes between legal and extralegal factors. Legal factors are those things that we accept as legitimately, as a matter of law, mitigating or aggravating criminal sentences. Such things as the seriousness of the offense and the defendant’s prior criminal record fall into this category. Extralegal factors include things like class, race, and gender. These are regarded as illegitimate factors in determining criminal sentences. They have nothing to do with the defendant’s criminal behavior, and everything to do with the defendant’s status as a member of a particular group.

One way to measure racial disparity is to compare the proportion of people that are members of a particular group (their proportion in the general population) with the proportion or that group at a particular stage in the criminal justice system. In 2013, the Bureau of the Census (Bureau of the Census, 2014) estimated that African-Americans made up 13.2% of the population of the United States. According to the FBI, 28.4% of all arrestees were African-American. From this information we can see that the proportion of African-Americans arrested was just over double what one would expect. The population of African-Americans is 13.2%, however they are arrested at a percentage that is double (28%) of their population. This demonstrates they may be arrested more often than would be expected.

The disparity is more pronounced when it comes to drug crime. According to the NAACP (2014), “African Americans represent 12% of the total population of drug users, but 38% of those arrested for drug offenses, and 59% of those in state prison for a drug offense.” There are three basic explanations for these disparities in the criminal justice system. The first is individual racism. Individual racism refers to a particular person’s beliefs, assumptions, and behaviors. This type of racism manifests itself when the individual police officer, defense attorney, prosecutor, judge, parole board member, or parole officer is bigoted. Another explanation of racial disparities in the criminal justice system is institutional racism. Institutional racism manifests itself when departmental policies (both formal and informal), regulations, and laws result in unfair treatment of a particular group. A third (and controversial) explanation is differential involvement in crime. The basic idea is that African-Americans and Hispanics are involved in more criminal activity. Often this is tied to social problems such as poor education, poverty, and unemployment.

While it does not seem that bigotry is present in every facet of the criminal and juvenile justice systems, it does appear that there are pockets of prejudice within both systems. It is difficult to deny the data: Discrimination does take place in such areas as use of force by police and the imposition of the death penalty. Historically, nowhere was the disparity more discussed and debated than in federal drug policy. While much has recently changed with the passage of the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010, federal drug law was a prime example of institutional racism at work.

Note

Think about it . . . Racism in Law Enforcement

“Is racism an intractable problem for the police, or can other factors explain the disparate rate at which African-Americans are stopped and arrested?”

This is the introduction to a New York Times opinion series called “Black, White, and Blue” which consist of several opinion articles written for the NYT on the subject of racism in American law enforcement. Read these articles. Do you agree with their conclusions and solutions? Disagree? Why?

- : A Racist System? is shared under a CC BY 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by LibreTexts.

: Prison Overcrowding

In the 1980’s, the crime rate in America exploded. While many factors affected the rise, most scholars indicated that the rise was due to drug trafficking and gang activity. Drug traffickers and gangs protected their “turf” by killing the competition. Media would report nightly on the impact it was having in neighborhoods and society demanded action. Legislation responded by creating harsher sentencing laws. Mandatory minimum sentences and three strikes laws greatly changed the way we managed prisons. It led to longer sentences and prison overcrowding. To compound prison overcrowding, many of the offenders who are released are only returned to custody for parole violations. This is called recidivism. According to the California Department of Correction and Rehabilitation, in the early 2000’s the recidivism rate was approximately 65%, reaching its highest point in 2005-2006 where it was 67.5%. By the 2000’s the prison population had reached epidemic proportion.

Figure 1.4 Overcrowding in California State Prison. Public Domain.

Prison overcrowding reached epidemic proportions in California. The inmates filed lawsuits stating their Eighth Amendment rights were being violated. This led to action by the U.S. Supreme Court requiring the state to take immediate action to reduce its population.

California’s prisons are currently designed to house approximately 85,000 inmates. At the time of the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2011 decision in Brown v. Plata, the California prison system housed nearly twice that many (approximately 156,000 inmates). The Supreme Court held that California’s prison system violated inmates’ Eighth Amendment rights. The Court upheld a three-judge panel’s order to decrease the population of California’s prisons by an estimated 46,000 inmates.

-Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, University of California-Davis School of Medicine, 2230 Stockton Boulevard, 2nd Floor, Sacramento, CA 95818, USA. wjnewmanmd@gmail.com

Note

Pin It! Brown v. Plata Case Study

Follow the link to understand the impact Brown v. Plata had on Prison overcrowding.

But this is not unique to California, across the United States our prison populations are among the highest in the world. According to a report prepared by American Psychological Association, “One out of every 100 American adults is incarcerated, a per capita rate five to 10 times higher than that in Western Europe or other democracies, the report found.” While there is no easy answer, it is safe to say that we must evaluate the current system and find progressive ways to deal with crime and the criminal offender.

Mandatory Minimum Sentences

In the mid 1980’s, legislators created mandatory minimum sentences for many drug crimes. The Anti-Drug Act created in 1986 dramatically increased the sentences ordered for certain drug charges. The sentences increased depending on the drug and the amount. Many of these sentences started at 10 years in prison up to Life. But this legislation took away the power and discretion of judges. Now the district attorney had significantly more power, based on the charges filed offenders could be facing significant

prison time. They would likely plead to a lesser charge than facing a trial where they would be sentenced to prison for decade to Life.

These mandatory minimums which started at the Federal level were soon adopted by the state. But many of these mandatory minimum sentences were applied to low level drug offenders, not the “high-level” suppliers or importers Congress intended the laws to address. Most of these lengthy sentences were handed out to drug couriers, street level dealers or even friends or families of drug offenders.

But reforms are in the works. Recognizing these laws did not have the intended outcomes, judges and citizens have been advocating for repealing these laws and return sentencing power to judges. Several states have already repealed the laws, but more need to follow.

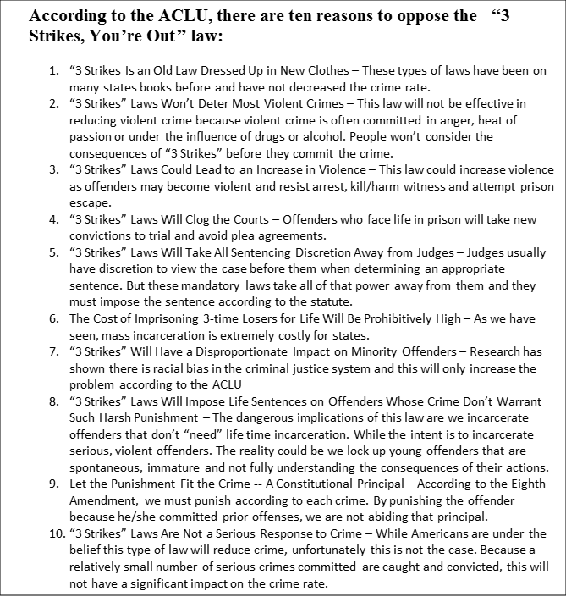

Three-Strikes Law

Three-Strikes legislation, often referred to as habitual offender laws impose harsher sentences for certain crimes (often violent offenses) for repeated violations. For example, in California after the first offense, the second and third crime could result in double the sentence, up to life in prison.

Three Strikes law was to require a defendant convicted of any new felony, having suffered one prior conviction of a serious felony as defined in section 1192.7(c), a violent felony as defined in section 667.5(c), or a qualified juvenile adjudication or out-of-state conviction (a “strike”), to be sentenced to state prison for twice the term otherwise provided for the crime. If the defendant was convicted of any felony with two or more prior strikes, the law mandated a state prison term of at least 25 years to life.

This law was designed to incapacitate offenders (through long sentences) and deter others from committing crimes due to the consequences they will face. But again, this mandatory sentencing took the power away from judges to determine the appropriate sentence based on the crime, offender, victim and circumstances. This law, like mandatory minimum drug sentencing has dramatically increased the American prison population. The intent of this law was to reduce serious, repeat offenders and permanently incapacitate offenders who do not “learn their lesson.” However, critics argue that the law has been used to incorrectly and incarcerate offenders unnecessarily

Figure 1.4 3 Strikes Law is under a CC BY 4.0 license.

Recidivism

Another dynamic issue facing prison overcrowding is recidivism. Recidivism is when offenders are returned to custody for a probation/parole violation or after committing a new offense. Often times offenders are returned to custody not for a new law

violation, but what is called a technical violation of community supervision. This is when an offender violates a court order or probation/parole officer’s directive. Usually officials work with offenders before returning them to custody using informal sanctions. But if the offender continues to disregard directives or commits a serious violation of a term; for example, a domestic violence offender harassing the victim; they can be returned to incarceration. When community supervision is revoked, a hearing is held before a judge. Depending on the violation, they could be returned to custody for a short time, or to complete the remainder of their commitment. This hearing is often called a revocation hearing.

Recent changes in California has been implemented to address recidivism and prison population. Enacted in 2011, AB 109 Public Safety Realignment was implemented to address recidivism and prison overcrowding. While there are many facets of this legislation, the biggest change was transferring a significant amount of criminal supervision to local probation departments and out of prison/parole supervision. For a select number of “non-violent” offenses, offenders who used to go to prison would now remain in local custody and released to county probation supervision instead of going to prison. The state redirected funds to county law enforcement agencies to fund evidence-based programs to reduce recidivism. (Evidence-Base Practices will be discussed in the next section.

This realignment had a significant impact on local law enforcement agencies, especially local jails and probation departments. A significant number of offenders would remain the counties responsibility. Jails had to deal with an increased population they were not built to deal with and also longer incarceration rates. Historically, California jails only housed offender sentenced to one year or less. After AB 109, sentences could go as has as decades. Jails were not designed to house offenders’ long term, so this has been a struggle for many local jails. They also didn’t have rehabilitative programs in place for long term offenders. The state has provided jails with funding to establish evidence-based treatment programs in their facilities.

Probation departments were also significantly impacted by the realignment. They now had different classifications of offenders with specific terms of supervision. Historically, probation departments supervised offenders in the community in lieu of a lengthy prison sentence. As long as they complied with the terms and conditions outlined in their sentence, they could remain in the community. If they complied for the term of supervision (usually 3-5 years) they would be successfully completed and could even have their conviction reduce in certain circumstances. However, if they failed to comply; probation could be revoked, and they were then sentenced to prison to serve their commitment. This is called Felony Probation. After realignment, there were two additional probation supervision types: Mandatory Supervision and Post-Release Community Supervision.

Mandatory Supervision was a sentence ordered by the court for felony crimes determined to be “non-violent” and not requiring prison time. These offenders would serve time in local custody and released to probation supervision when jail determined they completed their commitment. (Of course, jail population and overcrowding lead to early releases). The judge orders the in-custody and supervision time at sentencing. For example, for the crime where the confinement time is six years. The judge can order one, two or more years in custody with the remainder of under mandatory supervision. If the judge orders one year in jail, they would spend the remaining five years under Mandatory Supervision. Post-Release Community Supervision is a grant of supervision that occurs after the offender completes this prison commitment but has been determined to be a “non-violent” offender and place under the supervision of a probation officer instead of a parole agent. The term of supervision is one year and if they remain violation free during that one-year period, they are terminated from supervision.

Again, this greatly increased the number of offenders under probation supervision. The state funded the local county probation department for staffing. The state also funded local probation departments for evidence-based treatment programs to address these new offenders.

- : Prison Overcrowding is shared under a CC BY 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by LibreTexts.

: States Shifting Focus from Incarceration to Rehabilitation

As the prison populations continued to climb through the decades, more and more states are looking for ways to ease the population. The current direction many states are taking is to release “non-violent” offenders and provide rehabilitation services. In this section we review the practice and policy of offender rehabilitation. Rehabilitation programs are nothing new, this idea, once called the medical model dates back to the 1940’s and seeks to treat criminal behavior through treatment as opposed to punishment and incarceration. It lost favor in the 1970’s when correctional professionals determined rehabilitation didn’t work. However, significant research into criminal behavior and new assessment tools have led to a renewal of interest in this method of dealing with crime.

Rehabilitation Programs

Rehabilitation programs are nothing new to the criminal justice system. For many decades we have been providing substance abuse treatment programs, drug diversion programs, domestic violence and DUI treatment programs to deal with illegal behavior with varying success. However, as states have tried to address the overcrowding in jails and prisons, they have tried to apply more treatment programs to what they call “non-violent” offenders. Often this “non-violent” classification addresses drug offenders and offenders convicted of property offenses.

As previously indicated, The State of California passed legislation – AB 109 Realignment – that transferred the incarceration and supervision of these offenders out of state control (prison/parole) to local (jail/probation) control. The theory behind this transition was that local government could provide better treatment options to this non-violent offender and maintain public safety. The State awards local governments funding based on their treatment options and success in reducing recidivism. However, the State also required that the programs met specific goals and the agencies had to adopt “evidence-based” practices to be compliant with to receive funding.

Evidence-Base Practices

According to the National Institute of Corrections, the definition of evidence-based practices is as following:

Evidence-based practice (EBP) is the objective, balanced, and responsible use of current research and the best available data to guide policy and practice decisions, such that outcomes for consumers are improved. Used originally in the health care and social science fields, evidence-based practice focuses on approaches demonstrated to be effective through empirical research rather than through anecdote or professional experience alone.

An evidence-based approach involves an ongoing, critical review of research literature to determine what information is credible, and what policies and practices would be most effective given the best available evidence. It also involves rigorous quality assurance and evaluation to ensure that evidence-based practices are replicated with fidelity, and that new practices are evaluated to determine their effectiveness.

In contrast to the terms “best practices” and “what works,” evidence-based practice implies that 1) there is a definable outcome(s);

2) it is measurable; and 3) it is defined according to practical realities (recidivism, victim satisfaction, etc.). Thus, while these three terms are often used interchangeably, EBP is more appropriate for outcome-focused human service disciplines.

This shift in theory drastically changed the way in which correctional facilities and community correction officers managed the treatment of offenders. These agencies were now required to not only state they were making an impact through statistical date, but also needed to provide programs which could also show positive influence on offender behavior. New ways of assessing offenders’ risk to reoffend and determination of criminogenic needs were needed. These tools allow officers to not only use their “professional judgement,” but a validated tool that could provide scientific support to the likelihood and offender would reoffend. These tools also allowed officers to identify those offenders who were at the highest risk to reoffend. Officers could then focus attention (supervision/public safety) and support towards those offenders while allowing moderate and low risk offenders to be placed in more appropriate treatment.

Risk Assessments Tools and Criminogenic Needs

The ability to predict the likelihood to reoffend and determine an offender’s criminogenic needs is important to provide officers and offenders with the appropriate treatment plan. By identifying the offenders who need the most intensive supervision, agencies can allocate the resources to those high-risk individuals. This means officer can provide a higher level of supervision to the right classification of offender. It also allows means officers with these high-risk offenders have lower caseloads. Research indicates that officers who supervise high risk offenders should be in the range of 30-50 offenders. The next step in the process is to conduct

detail comprehensive interviews with the offender to identify the specific criminogenic needs of the offender and prepare a case plan. This case plan is shared with the offender, so he become part of his/her rehabilitation. Offenders are not always willing to participate with treatment and this can cause delay in treatment and may require to be returned to custody.

Another important aspect of this approach is that by identify each offender’s risk to reoffend we avoid mixing the population of offenders. For example, high-risk offenders are generally more criminally sophisticated the low or moderate offenders. If we integrate all offenders in similar treatment programs we run the risk of affecting or influencing low/moderate offender with higher risk offenders thereby increasing their risk to reoffend. The higher-risk offenders could negatively influence low/moderate risk offenders when they interact. Significant amount of research indicate low/moderate risk will often complete community supervision with limited contact with supervision officers.

- : States Shifting Focus from Incarceration to Rehabilitation is shared under a CC BY 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by LibreTexts.