14 5: Types of Correctional Facilities

Key Terms:

Federal/State/Local Facilities Pre-trial Detention

Security Levels (Inmates) Medium Security Supermax Prisons

Custody Levels Punishment Minimum Security Maximum Security

: Federal level

The Federal Bureau of Prisons was established in 1930 to provide more progressive and humane care for federal inmates, to professionalize the prison service, and to ensure consistent and centralized administration of the 11 Federal prisons in operation at that time. Today, the Bureau includes 121 institutions, 6 regional offices, a Central Office (headquarters), and 26 offices that oversee residential reentry centers. The regional offices and Central Office provide oversight and administrative support to the institutions and offices. The Bureau is responsible for the care and custody of more than 208,000 federal inmates, as of spring 2015.1 About 81 percent of these inmates are confined in federal correctional institutions or detention centers, and the remainder are held in secure privately managed or community-based facilities and local jails under contract with the Bureau. The Bureau protects society by confining offenders in prisons and community-based facilities that are safe, humane, cost-efficient, and appropriately secure, and by providing inmates with programs and services to assist them in becoming proactive law-abiding citizens when they return to their communities. The Bureau’s most important resource is its staff. All Bureau staff are expected to conduct themselves in a manner that creates and maintains respect for the agency, the Department of Justice, the Federal Government, and the law.

The Bureau operates institutions at four security levels (minimum, low, medium, and high) and has one maximum-security prison for the less than one percent of inmates who require that level of security. It also has administrative facilities, such as pretrial detention centers and medical referral centers that have specialized missions and confine offenders of all security levels. The Bureau also classifies its institutions based on the level of medical services readily available, as care levels 1-4. The characteristics that help define the security level of an institution are perimeter security (such as fences, patrol officers, and towers), level of staffing, internal controls for inmate 3 movement and accountability, and type of living quarters (for example, cells or open dormitories).

The Bureau’s graduated security and medical classification levels allow staff to assign an inmate to an institution in accordance with his/her individual needs. Thus, inmates who can function with relatively less supervision, without disrupting institution operations or threatening the safety of staff or other inmates, can be housed in lower security level institutions. Regardless of the specific discipline in which a staff member works, all employees are “correctional workers first.” This means everyone is responsible for the security and good order of the institution. All staff are expected to be vigilant and attentive to inmate accountability and security issues, to respond to emergencies, and to maintain a proficiency in custodial and security matters, as well as in their particular job specialty. This approach allows the Bureau to operate in the most cost-effective manner with fewer correctional officers and still maintain direct supervision of inmates.

The Bureau relies on security technologies to help ensure the safety of staff and inmates. Recently new technologies have included whole body imaging devices to detect contraband (including cell phones) and sophisticated walk-through metal detectors, thermal fencing, and thermal camera sensors. These technologies have significantly reduced contraband. Additionally, the Bureau has provided staff additional equipment, such as oleoresin capsicum spray, to further enhance safety.

The Bureau’s philosophy is that preparation for reentry to society begins on the first day of incarceration. Accordingly, the Bureau provides many programs, designed to assign inmates and address their needs such as substance abuse treatment, mental health treatment, education, anger management, parenting and more. Prison work programs provide inmates an opportunity to acquire marketable occupational skills, as well as acquire a sound work ethic and habits. Medically able inmates are required to work some. For some individuals, this represents their first employment experience. Work assignments provide on-the-job training similar to what would be received in the community. For example, inmates work as clerks, landscapers, and electricians. Many work assignments are linked to vocational training programs and may lead to formal apprenticeships.

- Federal Prison Industries (FPI) and Vocational Training Federal Prison Industries (FPI), trade name UNICOR, is one of the Bureau’s most important correctional programs. It has been proven to substantially reduce recidivism and operates without congressional appropriation. Inmates who participate in FPI are also substantially less likely to engage in misconduct.

- Education: The Bureau provides education and recreation programs individually: GED, Spanish GED, English As A Second Language, 6 Adult Continuing Education, Post-Secondary, Parenting, Vocational, Apprenticeships, and Release Preparation. Inmates who participate in education programs for a minimum of six months are less likely to recidivate when compared to similar nonparticipating inmates. Recreation programs help teach inmates to make constructive use of leisure time to reduce stress, improve their health and develop hobbies they enjoy. These programs keep inmates constructively occupied and contribute to positive lifestyles and self-improvement.

- Inmate Faith-Based Programs Federal prisons offer a variety of faith-based services and programs. Inmates are granted permission to wear or retain various religious items, and accommodations are made to observe holy days. Bureau facilities offer religious diets that meet the dietary requirements of various faith groups, such as the Jewish and Islamic faiths. Most institutions

have sweat lodges to accommodate the religious requirements of Native Americans. Religious programs are led or supervised by staff chaplains, contract spiritual leaders, and community volunteers. Chaplains oversee inmate worship services and self- improvement programs, and provide pastoral care, spiritual guidance, and counseling. The Bureau offers inmates the opportunity to participate in its Life Connections Program, a residential reentry program as well as Thresholds, the nonresidential version of our program.

- Residential Substance Abuse Treatment Residential drug abuse treatment programs (RDAPs) are offered at more than 77 Bureau institutions, providing treatment to more than 18,000 inmates each year. Inmates in RDAP are housed in a separate housing unit that operates a modified therapeutic community. RDAPs provide intensive half-day programming, 5 days a week, for 9-12 months. The remainder of each day is spent in education, work skills training, and other programs. The program also includes a community- based component that inmates complete while in a RRC or home confinement. Inmates who complete RDAP are 16 percent less likely to recidivate and 15 percent less likely to have a relapse to drug use within 3 years after release. Nonviolent offenders who complete the program are eligible to have their sentence reduced by up to one year. Other drug programs offered by the Bureau are the Nonresidential Drug Treatment Program, Challenge Program, and Spanish RDAP.

- Pro-Social Values Programs Encouraged by RDAP’s positive results, the Bureau implemented a number of other programs, including the Secure Mental Health Treatment Program, which treats inmates with serious mental illness and histories of significant violence; the Challenge Program for high security inmates, which treats inmates with a history of substance abuse or mental illness; the Resolve Program for female inmates, which treats inmates with trauma-related mental illnesses; the BRAVE (Bureau Rehabilitation and Values Enhancement) Program for younger, newly-designated offenders, which addresses anti-social attitudes and behavior; the Skills Program for cognitively-impaired inmates, which treats issues with adapting to prison and the community; Mental Health Step Down Units, which provide treatment for inmates with serious mental illnesses releasing from psychiatric hospitalization; the Sex Offender Treatment Program for inmates with a sex offense history; and the STAGES (Steps Toward Awareness, Growth, and Emotional Strength) program for inmates with severe personality disorders, who have a history of behavioral problems or self-harm. As resources allow, the Bureau has expanded these programs to address the significant demand for these services. The Bureau has found that these programs significantly reduce institution misconduct.

Near the end of their sentence, inmates participate in the Release Preparation Program, which includes a series of classes regarding daily living activities in the community including employment, banking, resume writing, job search strategies, and job retention. It also includes presentations by representatives from community-based organizations that help former inmates find employment and training opportunities after release. The Bureau helps inmates maintain ties with their family and friends through visiting, mail, email and the telephone.

The Bureau specifically encourages inmates to maintain and develop bonds with their children through parenting programs that include specialized activities such as day camps and workshops. The Bureau’s Inmate Transition Branch helps inmates prepare release portfolios that include a resume, education and training certificates and transcripts, diplomas, and other significant documents needed to secure employment. Many institutions hold mock job fairs to allow inmates to practice job interview techniques and expose community recruiters to the skills available among inmates.

- : Federal level is shared under a CC BY 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by LibreTexts.

: State Level

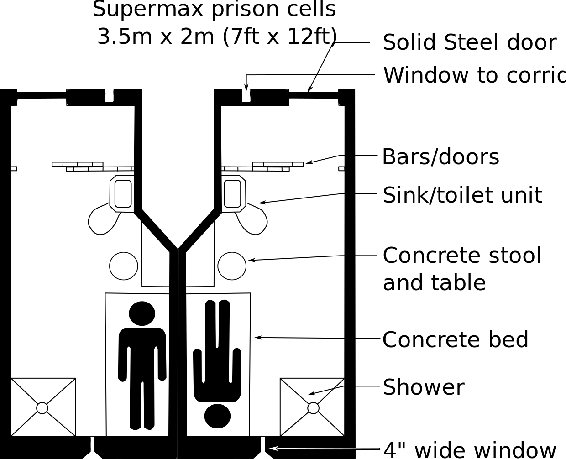

Prisons in the United States today are usually distinguished by custody levels. Super-maximum-security prisons are used to house the most violent and most escape prone inmates. These institutions are characterized by almost no inmate mobility within the facility, and fortress-like security measures. This type of facility is very expensive to build and operate. The first such prison was the notorious federal prison Alcatraz, built by the Federal Bureau of Prisons in 1934.

Maximum-security prisons are fortresses that house the most dangerous prisoners. Only 20% of the prisons in the United States are labeled as maximum security, but, because of their size, they hold about 33% of the inmates in custody. Because super-max prisons are relatively rare, maximum-security facilities hold the vast majority of America’s dangerous convicts. These facilities are characterized by very low levels of inmate mobility, and extensive physical security measures.

Figure 5.1 Artist’s render of a supermax prison cell, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International

Tall walls and fences are common features, usually topped with razor wire. Watchtowers staffed by officers armed with rifles are common as well. Security lighting and video cameras are almost universal features.

States that use the death penalty usually place death row inside a maximum-security facility. These areas are usually segregated from the general population, and extra security measures are put in place. Death row is often regarded as a prison within a prison, often having different staff and procedures than the rest of the facility.

Medium-security prisons use a series of fences or walls to hold prisoners that, while still considered dangerous, are less of a threat than maximum-security prisoners. The physical security measures placed in these facilities is often as tight as for maximum- security institutions. The major difference is that medium-security facilities offer more inmate mobility, which translates into more treatment and work options. These institutions are most likely to engage inmates in industrial work, such as the printing of license plates for the State.

Minimum-security prisons are institutions that usually do not have walls and armed security. Prisoners housed in minimum-security prisons are considered to be nonviolent and represent a very small escape risk. Most of these institutions have far more programs for inmates, both inside the prison and outside in the community. Part of the difference in inmate rights and privileges stems from the fact that most inmates in minimum-security facilities are “short timers.” In other words, they are scheduled for release soon. The idea is to make the often-problematic transition from prison to community go more smoothly. Inmates in these facilities may be assigned there initially, or they may have worked their way down from higher security levels through good behavior and an approaching release date.

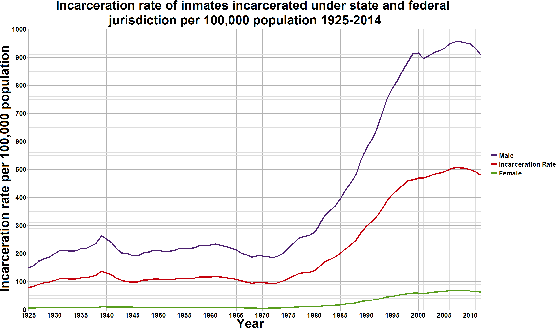

Women are most often housed in women’s prisons. These are distinguished along the same lines as male institutions. These institutions tend to be smaller than their male counterparts are, and there are far fewer of them. Women do not tend to be as violent as men are, and this is reflected in what they are incarcerated for.

Figure 5.2 Male v. Female Incarceration Rates in the U.S., Image is in the public domain.

Most female inmates are incarcerated for drug offenses. Inmate turnover tends to be higher in women’s prisons because they tend to receive shorter sentences.

A few states operate coeducational prisons where both male and female inmates live together. The reason for this is that administrators believe that a more normal social environment will better facilitate eventual reintegration of both sexes into society. The fear of predation by adult male offenders keeps most facilities segregated by gender.

In the recent past, the dramatic growth in prison populations led to the emergence of private prisons. Private organizations claimed that they could own and operate prisons more efficiently than government agencies can. The Corrections Corporation of America is the largest commercial operator of jails and prisons in the United States. The popularity of the idea has waned in recent years, mostly due to legal liability issues and a failure to realize the huge savings promised by the private corporations.

- : State Level is shared under a CC BY 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by LibreTexts.

: Local Level

The idea of jails has a long history, and the historical roots of American jails are in the “gaols” of feudal England. Sheriffs operated these early jails, and their primary purpose was to hold accused persons awaiting trial. This English model was brought over to the Colonies, but the function remained the same. In the 1800s, jails began to change in response to the penitentiary movement. Their function was extended to housing those convicted of minor offenses and sentenced to short terms of incarceration. They were also used for other purposes, such as holding the mentally ill and vagrants. The advent of a separate juvenile justice system and the development of state hospitals alleviated the burden of taking care of these later categories.

Today’s jails are critical components of local criminal justice systems. They are used to address the need for secure detention at various points in the criminal justice process. Jails typically serve several law enforcement agencies in the community, including local law enforcement, state police, wildlife conservation officers, and federal authorities. Jails respond to many needs in the criminal justice system and play an integral role within every tier of American criminal justice. These needs are ever changing and influenced by the policies, practices, and philosophies of the many different users of the jail. Running a jail is a tough business, usually undertaken by a county sheriff. Often, much of the Sheriff’s authority is delegated to a jail administrator.

Running a jail is such a complicated endeavor partly because jails serve an extremely diverse population. Unlike prisons where inmate populations are somewhat homogenous, fails hold vastly different individuals. Jails hold both men and women, and both children and adults. Most state prisoners are serious offenders, whereas jails old both serious offenders as well as minor offenders who may be vulnerable to predatory criminals. Those suffering from mental illness, alcoholism, and drug addiction often find themselves in jail. It is in this environment that jail staff must accomplish the two major functions of jails: Intake and Custody.

Booking and Intake

The booking and intake function of jails serves a vital public safety function by providing a secure environment in which potentially dangerous persons can be assessed, and the risk these individuals pose the public can be determined.

Custody

The second major function of jails is the idea of custody. That is, people are deprived of their liberty for various reasons. The two most common of these reasons are pretrial detention and punishment.

Pretrial Detention

A major use of modern jails is what is often referred to as pretrial detention. In other words, jails receive accused persons pending arraignment and hold them awaiting trial, conviction, or sentencing. More than half of jail inmates are accused of crimes and are awaiting trial. The average time between arrest and sentencing is around six months. Jails also readmit probation and parole violators and absconders, holding them for judicial hearings. The major purpose of pretrial detention is not to punish offenders, but to protect the public and ensure the appearance of accused persons at trial.

According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, there are around 3,300 jails currently in operation within the United States. This large number points to a very important fact: Jails are primarily a local concern. Jails (and detention centers) are facilities designed to safely and securely hold a variety of criminal offenders, usually for a short period. The wide variety of offenders comes from the fact that jails have dual roles. They hold criminal defendants waiting on processing by the criminal justice system, and they hold those convicted of crimes and sentenced to a jail term. In addition, jails hold prisoners for other agencies, such as state departments of correction, until bed space becomes available in a state prison.

Figure 5.2 Jail Cell. Free to use by Pixaby

The size of jails can vary widely depending on the jurisdiction the facility serves. Both geographic and legal jurisdiction must be considered. The single most important determinant of jail size is population density. The more people a given jurisdiction has, the more jail inmates they are likely to have. Many rural jails are quite small, but America’s largest population centers tend to have massive jail complexes. Most counties and many municipalities operate jails, and a few are operated by federal and other non-local agencies. There has been a trend for small, rural jurisdictions to combine their jails into regional detention facilities. These consolidated operations can increase efficiency, security, and better ensure prisoners’ rights.

Punishment

A primary function of jails is to house criminal defendants after arrest. Within a very narrow window of time, the arrestee must appear before a judge. The judge will consider the charges against the defendant and the defendant’s risk of flight when determining bail. The judge may decide to remand the defendant to the custody of the jail until trial, but this is rare. Most often, pretrial release will be granted. The arrestees may be required to pay a certain amount of money to ensure their appearance in court, or they may be released on their own recognizance.

As a criminal sanctioning option, jails provide a method of holding offenders accountable for criminal acts. Jails house offenders that have been sentenced to a jail term for misdemeanor offenses, usually for less than one year. There are many ways that jail sentences can be served, depending largely on the laws and policies of the particular jurisdiction. A central goal of incarceration as punishment in the criminal justice system is the philosophical goal of deterrence. Many believe that jail sentences discourage offenders from committing future criminal acts (specific deterrence) and to potential criminals about the possible costs of crime (general deterrence). Rehabilitation and reintegration are sometimes considered secondary goals of incarceration. These goals are not usually deemed amenable to the jail environment, and few programs designed to meet these goals exist. Many local jails do make a modest effort to provide inmates with opportunities for counseling and change to deter future criminal behavior, but always within the constraints of scant resources.

Miscellaneous Functions

Jails in some jurisdictions are responsible for transferring and transporting inmates to federal, state, or other authorities. Jails are also tasked with holding mentally ill persons pending their transfer to suitable mental health facilities where beds are often unavailable. Jails also hold people for a variety of government purposes; they hold individuals wanted by the armed forces, for protective custody of individuals who may not be safe in the community, for those found in contempt of court, and witnesses for

the courts. Jails often hold state and federal inmates due to overcrowding in prison facilities. Jails are commonly tasked with community-based sanctions, such as work details engaged in public services.

Jail Populations

Arrestees often arrive at the jail with myriad many problems. Substance abuse, alcohol abuse, and mental illness often mean that jail inmates are not amenable to complying with the directions of jail staff. Many have medical problems, psychological problems, and emotional problems. Inmates can display the full gambit of human emotions: fail staff may see fear, anxiety, anger, and depression every day. Behaviors often mirror emotional state, and at times staff must deal with noncompliant, suicidal, or violent inmates. While inmates are in custody, the jail is responsible for their health and wellbeing.

Jails function in a role as a service provider for the rest of the criminal justice community. Jail administrators have very little discretion in who goes to jail and how long they remain in custody. Law and policy play a big role in dictating who goes to jail, as do the discretionary decisions of probation and parole officers, law enforcement, and judges. Prevalent community attitudes are also important, because voters can place pressure on law enforcement and the courts to make more arrests and prosecute more offenders. When this happens, more people end up in jail.

- : Local Level is shared under a CC BY 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by LibreTexts.