15 6: Institutionalization of Inmates in Correctional Facilities

Key Terms:

|

Institutionalization |

Prison “norms” |

|

“Just Desserts” |

Diminished self worth |

|

Hypervigilance |

PTSD |

|

Alienation |

Dependence on structure |

|

Social withdrawl |

Prison culture |

- : The State of the Prisons

- : The Psychological Effects of Incarceration- On the Nature of Institutionalization

- : Dependence on institutional structure and contingencies

- : Hypervigilance, interpersonal distrust, and suspicion

- : Emotional over-control, alienation, and psychological distancing

- : Social withdrawal and isolation

- : Incorporation of exploitative norms of prison culture

- : Diminished sense of self-worth and personal value

- : Post-traumatic stress reactions to the pains of imprisonment

This page titled 6: Institutionalization of Inmates in Correctional Facilities is shared under a CC BY 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by Dave Wymore & Tabitha Raber.

: The State of the Prisons

Prisoners in the United States and elsewhere have always confronted a unique set of contingencies and pressures to which they were required to react and adapt in order to survive the prison experience. However, over the last several decades beginning in the early 1970s and continuing to the present time a combination of forces has transformed the nation’s criminal justice system and modified the nature of imprisonment. The challenges prisoners now face in order to both survive the prison experience and, eventually, reintegrate into the free world upon release have changed and intensified as a result.

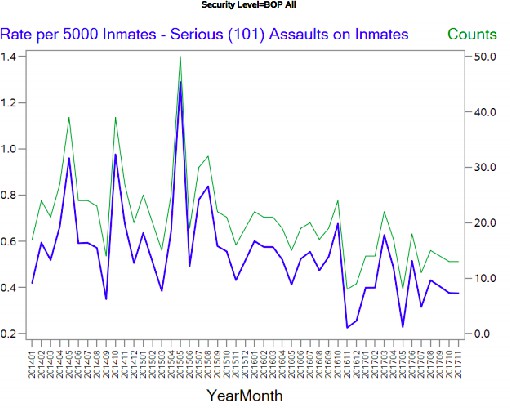

Figure 6.1 Bureau of Prison Statistics March 2018 Report.

Among other things, these changes in the nature of imprisonment have included a series of inter-related, negative trends in American corrections. Perhaps the most dramatic changes have come about as a result of the unprecedented increases in rate of incarceration, the size of the U.S. prison population, and the widespread overcrowding that has occurred as a result. Over the past 25 years, penologists repeatedly have described U.S. prisons as “in crisis” and have characterized each new level of overcrowding as “unprecedented.” By the start of the 1990s, the United States incarcerated more persons per capita than any other nation in the modern world, and it has retained that dubious distinction for nearly every year since. The international disparities are most striking when the U.S. incarceration rate is contrasted to those of other nations to whom the United States is often compared, such as Japan, Netherlands, Australia, and the United Kingdom. In the 1990s, as Marc Mauer and the Sentencing Project have effectively documented the U.S. rates have consistently been between four and eight times those for these other nations.

The combination of overcrowding and the rapid expansion of prison systems across the country adversely affected living conditions in many prisons, jeopardized prisoner safety, compromised prison management, and greatly limited prisoner access to meaningful programming. The two largest prison systems in the nation California and Texas provide instructive examples. Over the last 30 years, California’s prisoner population increased eightfold (from roughly 20,000 in the early 1970s to its current population of approximately 160,000 prisoners). Yet there has been no remotely comparable increase in funds for prisoner services or inmate programming. In Texas, over just the years between 1992 and 1997, the prisoner population more than doubled as Texas achieved one of the highest incarceration rates in the nation. Nearly 70,000 additional prisoners added to the state’s prison rolls in that brief five-year period alone. Not surprisingly, California and Texas were among the states to face major lawsuits in the 1990s over substandard, unconstitutional conditions of confinement. Federal courts in both states found that the prison systems had failed to provide adequate treatment services for those prisoners who suffered the most extreme psychological effects of confinement in deteriorated and overcrowded conditions.

Paralleling these dramatic increases in incarceration rates and the numbers of persons imprisoned in the United States was an equally dramatic change in the rationale for prison itself. The nation moved abruptly in the mid-1970s from a society that justified putting people in prison on the basis of the belief that incarceration would somehow facilitate productive re-entry into the free world to one that used imprisonment merely to inflict pain on wrongdoers (“just deserts”), disable criminal offenders (“incapacitation”), or to keep them far away from the rest of society (“containment”). The abandonment of the once-avowed goal of rehabilitation certainly decreased the perceived need and availability of meaningful programming for prisoners as well as social

and mental health services available to them both inside and outside the prison. Indeed, it generally reduced concern on the part of prison administrations for the overall well-being of prisoners.

The abandonment of rehabilitation also resulted in an erosion of modestly protective norms against cruelty toward prisoners. Many corrections officials soon became far less inclined to address prison disturbances, tensions between prisoner groups and factions, and disciplinary infractions in general through ameliorative techniques aimed at the root causes of conflict and designed to de- escalate it. The rapid influx of new prisoners, serious shortages in staffing and other resources, and the embrace of an openly punitive approach to corrections led to the “de-skilling” of many correctional staff members who often resorted to extreme forms of prison discipline (such as punitive isolation or “supermax” confinement) that had especially destructive effects on prisoners and repressed conflict rather than resolving it. Increased tensions and higher levels of fear and danger resulted.

The emphasis on the punitive and stigmatizing aspects of incarceration, which has resulted in the further literal and psychological isolation of prison from the surrounding community, compromised prison visitation programs and the already scarce resources that had been used to maintain ties between prisoners and their families and the outside world.

Support services to facilitate the transition from prison to the free world environments to which prisoners were returned were undermined at precisely the moment they needed to be enhanced. Increased sentence length and a greatly expanded scope of incarceration resulted in prisoners experiencing the psychological strains of imprisonment for longer periods of time, many persons being caught in the web of incarceration who ordinarily would not have been (e.g., drug offenders), and the social costs of incarceration becoming increasingly concentrated in minority communities (because of differential enforcement and sentencing policies).

Thus, in the first decade of the 21st century, more people have been subjected to the pains of imprisonment, for longer periods of time, under conditions that threaten greater psychological distress and potential long-term dysfunction, and they will be returned to communities that have already been disadvantaged by a lack of social services and resources.

Video: Explaining Mass Incarceration in Under 4 minutes…

- : The State of the Prisons is shared under a CC BY 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by LibreTexts.

: The Psychological Effects of Incarceration- On the Nature of Institutionalization

The adaptation to imprisonment is almost always difficult and, at times, creates habits of thinking and acting that can be dysfunctional in periods of post-prison adjustment. Yet, the psychological effects of incarceration vary from individual to individual and are often reversible. To be sure, then, not everyone who is incarcerated is disabled or psychologically harmed by it. But few people are completely unchanged or unscathed by the experience. At the very least, prison is painful, and incarcerated persons often suffer long-term consequences from having been subjected to pain, deprivation, and extremely atypical patterns and norms of living and interacting with others.

The empirical consensus on the most negative effects of incarceration is that most people who have done time in the best-run prisons return to the free world with little or no permanent, clinically-diagnosable psychological disorders as a result. Prisons do not, in general, make people “crazy.” However, even researchers who are openly skeptical about whether the pains of imprisonment generally translate into psychological harm concede that, for at least some people, prison can produce negative, long-lasting change. And most people agree that the more extreme, harsh, dangerous, or otherwise psychologically-taxing the nature of the confinement, the greater the number of people who will suffer and the deeper the damage that they will incur.

Rather than concentrate on the most extreme or clinically-diagnosable effects of imprisonment, however, I prefer to focus on the broader and more subtle psychological changes that occur in the routine course of adapting to prison life. The term “institutionalization” is used to describe the process by which inmates are shaped and transformed by the institutional environments in which they live. Sometimes called “prisonization” when it occurs in correctional settings, it is the shorthand expression for the negative psychological effects of imprisonment. The process has been studied extensively by sociologists, psychologists, psychiatrists, and others, and involves a unique set of psychological adaptations that often occur in varying degrees in response to the extraordinary demands of prison life. In general terms, the process of prisonization involves the incorporation of the norms of prison life into one’s habits of thinking, feeling, and acting.

It is important to emphasize that these are the natural and normal adaptations made by prisoners in response to the unnatural and abnormal conditions of prisoner life. The dysfunctionality of these adaptations is not “pathological” in nature (even though, in practical terms, they may be destructive in effect). They are “normal” reactions to a set of pathological conditions that become problematic when they are taken to extreme lengths, or become chronic and deeply internalized (so that, even though the conditions of one’s life have changed, many of the once-functional but now counterproductive patterns remain).

Like all processes of gradual change, of course, this one typically occurs in stages and, all other things being equal, the longer someone is incarcerated the more significant the nature of the institutional transformation. When most people first enter prison, of course, they find that being forced to adapt to an often harsh and rigid institutional routine, deprived of privacy and liberty, and subjected to a diminished, stigmatized status and extremely sparse material conditions is stressful, unpleasant, and difficult.

However, the course of becoming institutionalized, a transformation begins. Persons gradually become more accustomed to the restrictions that institutional life imposes. The various psychological mechanisms that must be employed to adjust (and, in some harsh and dangerous correctional environments, to survive) become increasingly “natural,” second nature, and, to a degree, internalized. To be sure, the process of institutionalization can be subtle and difficult to discern as it occurs. Thus, prisoners do not “choose” to succumb to it or not, and few people who have become institutionalized are aware that it has happened to them. Fewer still consciously decide that they are going to willingly allow the transformation to occur.

The process of institutionalization is facilitated in cases in which persons enter institutional settings at an early age, before they have formed the ability and expectation to control their own life choices. Because there is less tension between the demands of the institution and the autonomy of a mature adult, institutionalization proceeds more quickly and less problematically with at least some younger inmates. Moreover, younger inmates have little in the way of already developed independent judgment, so they have little if anything to revert to or rely upon if and when the institutional structure is removed. And the longer someone remains in an institution, the greater the likelihood that the process will transform them.

Among other things, the process of institutionalization (or “prisonization”) includes some or all the following psychological adaptations.

- : The Psychological Effects of Incarceration- On the Nature of Institutionalization is shared under a CC BY 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by LibreTexts.

: Dependence on institutional structure and contingencies

Among other things, penal institutions require inmates to relinquish the freedom and autonomy to make their own choices and decisions and this process requires what is a painful adjustment for most people. Indeed, some people never adjust to it. Over time, however, prisoners may adjust to the muting of self-initiative and independence that prison requires and become increasingly dependent on institutional contingencies that they once resisted. Eventually it may seem more or less natural to be denied significant control over day-to-day decisions and, in the final stages of the process, some inmates may come to depend heavily on institutional decision makers to make choices for them and to rely on the structure and schedule of the institution to organize their daily routine. Although it rarely occurs to such a degree, some people do lose the capacity to initiate behavior on their own and the judgment to make decisions for themselves. Indeed, in extreme cases, profoundly institutionalized persons may become extremely uncomfortable when and if their previous freedom and autonomy is returned.

A slightly different aspect of the process involves the creation of dependency upon the institution to control one’s behavior. Correctional institutions force inmates to adapt to an elaborate network of typically very clear boundaries and limits, the consequences for whose violation can be swift and severe. Prisons impose careful and continuous surveillance and are quick to punish (and sometimes to punish severely) infractions of the limiting rules.

Figure 6.1 Which one? by Truid Radtke. (CC BY 4.0)

The process of institutionalization in correctional settings may surround inmates so thoroughly with external limits, immerse them so deeply in a network of rules and regulations, and accustom them so completely to such highly visible systems of constraint that internal controls atrophy or, in the case of especially young inmates, fail to develop altogether. Thus, institutionalization or prisonization renders some people so dependent on external constraints that they gradually lose the capacity to rely on internal organization and self-imposed personal limits to guide their actions and restrain their conduct. If and when this external structure is taken away, severely institutionalized persons may find that they no longer know how to do things on their own, or how to refrain from doing those things that are ultimately harmful or self- destructive.

- : Dependence on institutional structure and contingencies is shared under a CC BY 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by LibreTexts.

: Hypervigilance, interpersonal distrust, and suspicion

In addition, because many prisons are clearly dangerous places from which there is no exit or escape, prisoners learn quickly to become hypervigilant and ever-alert for signs of threat or personal risk. Because the stakes are high, and because there are people in their immediate environment poised to take advantage of weakness or exploit carelessness or inattention, interpersonal distrust and suspicion often result. Some prisoners learn to project a tough convict veneer that keeps all others at a distance. Indeed, as one prison researcher put it, many prisoners “believe that unless an inmate can convincingly project an image that conveys the potential for violence, he is likely to be dominated and exploited throughout the duration of his sentence.”

McCorkle’s study of a maximum-security Tennessee prison was one of the few that attempted to quantify the kinds of behavioral strategies prisoners report employing to survive dangerous prison environments. He found that “[f]ear appeared to be shaping the life-styles of many of the men,” that it had led over 40% of prisoners to avoid certain high-risk areas of the prison, and about an equal number of inmates reported spending additional time in their cells as a precaution against victimization. At the same time, almost three-quarters reported that they had been forced to “get tough” with another prisoner to avoid victimization, and more than a quarter kept a “shank” or other weapon nearby with which to defend themselves. McCorkle found that age was the best predictor of the type of adaptation a prisoner took, with younger prisoners being more likely to employ aggressive avoidance strategies than older ones.

- : Hypervigilance, interpersonal distrust, and suspicion is shared under a CC BY 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by LibreTexts.

: Emotional over-control, alienation, and psychological distancing

Shaping such an outward image requires emotional responses to be carefully measured. Thus, prisoners struggle to control and suppress their own internal emotional reactions to events around them. Emotional over-control and a generalized lack of spontaneity may occur as a result. Admissions of vulnerability to persons inside the immediate prison environment are potentially dangerous because they invite exploitation. As one experienced prison administrator once wrote: “Prison is a barely controlled jungle where the aggressive and the strong will exploit the weak, and the weak are dreadfully aware of it.” Some prisoners are forced to become remarkably skilled “self-monitors” who calculate the anticipated effects that every aspect of their behavior might have on the rest of the prison population and strive to make such calculations second nature.

Prisoners who labor at both an emotional and behavioral level to develop a “prison mask” that is unrevealing and impenetrable risk alienation from themselves and others, may develop emotional flatness that becomes chronic and debilitating in social interaction and relationships, and find that they have created a permanent and unbridgeable distance between themselves and other people. Many for whom the mask becomes especially thick and effective in prison find that the disincentive against engaging in open communication with others that prevails there has led them to withdrawal from authentic social interactions altogether. The alienation and social distancing from others are a defense not only against exploitation but also against the realization that the lack of interpersonal control in the immediate prison environment makes emotional investments in relationships risky and unpredictable.

- : Emotional over-control, alienation, and psychological distancing is shared under a CC BY 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by LibreTexts.

: Social withdrawal and isolation

Some prisoners learn to find safety in social invisibility by becoming as inconspicuous and unobtrusively disconnected from others as possible. The self-imposed social withdrawal and isolation may mean that they retreat deeply into themselves, trust virtually no one, and adjust to prison stress by leading isolated lives of quiet desperation. In extreme cases, especially when combined with prisoner apathy and loss of the capacity to initiate behavior on one’s own, the pattern closely resembles that of clinical depression. Long-term prisoners are particularly vulnerable to this form of psychological adaptation.

Figure 6.2 Isolation by Trudi Radtke. (CC BY 4.0)

Indeed, Taylor wrote that the long-term prisoner “shows a flatness of response which resembles slow, automatic behavior of a very limited kind, and he is humorless and lethargic.” In fact, Jose-Kampfner has analogized the plight of long-term women prisoners to that of persons who are terminally-ill, whose experience of this “existential death is unfeeling, being cut off from the outside (and who) adopt this attitude because it helps them cope.”

- : Social withdrawal and isolation is shared under a CC BY 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by LibreTexts.

: Incorporation of exploitative norms of prison culture

In addition to obeying the formal rules of the institution, there are also informal rules and norms that are part of the unwritten but essential institutional and inmate culture and code that, at some level, must be abided. For some prisoners this means defending against the dangerousness and deprivations of the surrounding environment by embracing all of its informal norms, including some of the most exploitative and extreme values of prison life. Note that prisoners typically are given no alternative culture to which to ascribe or in which to participate. In many institutions the lack of meaningful programming has deprived them of pro-social or positive activities in which to engage while incarcerated. Few prisoners are given access to gainful employment where they can obtain meaningful job skills and earn adequate compensation; those who do work are assigned to menial tasks that they perform for only a few hours a day. With rare exceptions those very few states that permit highly regulated and infrequent conjugal visits they are prohibited from sexual contact of any kind. Attempts to address many of the basic needs and desires that are the focus of normal day-to-day existence in the free world to recreate, to work, to love necessarily draws them closer to an illicit prisoner culture that for many represents the only apparent and meaningful way of being.

However, as I noted earlier, prisoner culture frowns on any sign of weakness and vulnerability and discourages the expression of candid emotions or intimacy. And some prisoners embrace it in a way that promotes a heightened investment in one’s reputation for toughness and encourages a stance towards others in which even seemingly insignificant insults, affronts, or physical violations must be responded to quickly and instinctively, sometimes with decisive force. In extreme cases, the failure to exploit weakness is itself a sign of weakness and seen as an invitation for exploitation. In men’s prisons it may promote a kind of hypermasculinity in which force and domination are glorified as essential components of personal identity. In an environment characterized by enforced powerlessness and deprivation, men and women prisoners confront distorted norms of sexuality in which dominance and submission become entangled with and mistaken for the basis of intimate relations.

Of course, embracing these values too fully can create enormous barriers to meaningful interpersonal contact in the free world, preclude seeking appropriate help for one’s problems, and a generalized unwillingness to trust others out of fear of exploitation. It can also lead to what appears to be impulsive overreaction, striking out at people in response to minimal provocation that occurs particularly with persons who have not been socialized into the norms of inmate culture in which the maintenance of interpersonal respect and personal space are so inviolate. Yet these things are often as much a part of the process of prisonization as adapting to the formal rules that are imposed in the institution, and they are as difficult to relinquish upon release.

?

Think about it . . . Stanford Prison Experiment

The Stanford Prison Experiment was a psychological study that tried to measure humans psychological responses to captivity, in particular, to life as a prisoner. It was conducted in 1971 by Philip Zimbardo of Stanford University. Since then other psychological researches have taken issue with the way Zimbardo conducted the experiment and claim that he skewed the conditions of the experiment and the findings. Click the links to do your own research and come to your own conclusion about this controversial study.

- : Incorporation of exploitative norms of prison culture is shared under a CC BY 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by LibreTexts.

: Diminished sense of self-worth and personal value

Prisoners typically are denied their basic privacy rights and lose control over mundane aspects of their existence that most citizens have long taken for granted. They live in small, sometimes extremely cramped and deteriorating spaces (a 60 square foot cell is roughly the size of king-size bed), have little or no control over the identity of the person with whom they must share that space (and the intimate contact it requires), often have no choice over when they must get up or go to bed, when or what they may eat, and on and on. Some feel infantalized and that the degraded conditions under which they live serve to repeatedly remind them of their compromised social status and stigmatized social role as prisoners.

Figure 6.3 Low Self-esteem. By Trudi Radtke. (CC BY 4.0)

A diminished sense of self-worth and personal value may result. In extreme cases of institutionalization, the symbolic meaning that can be inferred from this externally imposed substandard treatment and circumstances is internalized; that is, prisoners may come to think of themselves as “the kind of person” who deserves only the degradation and stigma to which they have been subjected while incarcerated.

- : Diminished sense of self-worth and personal value is shared under a CC BY 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by LibreTexts.

: Post-traumatic stress reactions to the pains of imprisonment

For some prisoners, incarceration is so stark and psychologically painful that it represents a form of traumatic stress severe enough to produce post-traumatic stress reactions once released. Moreover, we now understand that there are certain basic commonalities that characterize the lives of many of the persons who have been convicted of crime in our society. A “risk factors” model helps to explain the complex interplay of traumatic childhood events (like poverty, abusive and neglectful mistreatment, and other forms of victimization) in the social histories of many criminal offenders. As Masten and Garmezy have noted, the presence of these background risk factors and traumas in childhood increases the probability that one will encounter a whole range of problems later in life, including delinquency and criminality. The fact that a high percentage of persons presently incarcerated have experienced childhood trauma means, among other things, that the harsh, punitive, and uncaring nature of prison life may represent a kind of “re-traumatization” experience for many of them. That is, some prisoners find exposure to the rigid and unyielding discipline of prison, the unwanted proximity to violent encounters and the possibility or reality of being victimized by physical and/or sexual assaults, the need to negotiate the dominating intentions of others, the absence of genuine respect and regard for their wellbeing in the surrounding environment, and so on all too familiar. Time spent in prison may rekindle not only the memories but the disabling psychological reactions and consequences of these earlier damaging experiences.

Figure 2.4 PTSD. Image has been designated to the public domain by Q .under a CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication

The dysfunctional consequences of institutionalization are not always immediately obvious once the institutional structure and procedural imperatives have been removed. This is especially true in cases where persons retain a minimum of structure wherever they re-enter free society. Moreover, the most negative consequences of institutionalization may first occur in the form of internal chaos, disorganization, stress, and fear. Yet, institutionalization has taught most people to cover their internal states, and not to openly or easily reveal intimate feelings or reactions. So, the outward appearance of normality and adjustment may mask a range of serious problems in adapting to the free world.

This is particularly true of persons who return to the free world lacking a network of close, personal contacts with people who know them well enough to sense that something may be wrong. Eventually, however, when severely institutionalized persons confront complicated problems or conflicts, especially in the form of unexpected events that cannot be planned for in advance, the myriad of challenges that the non-institutionalized confront in their everyday lives outside the institution may become overwhelming. The facade of normality begins to deteriorate, and persons may behave in dysfunctional or even destructive ways because all of the external structure and supports upon which they relied to keep themselves controlled, directed, and balanced have been removed.

6.9: Post-traumatic stress reactions to the pains of imprisonment is shared under a CC BY 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by LibreTexts.