11 3: Correctional Clients

Key Terms:

The Texas Syndicate The Mexikanemi Crips and Bloods Career Criminals Elderly Criminals

- : Career Criminals

- : Criminal Gang Members

- : Managing Gangs in a Prison Setting

- : Accidental Criminals

- : Elderly Criminals

: Career Criminals

The United States Sentencing Commission was directed by Congress to set sentencing guidelines for repeat violent offenders or repeat drug trafficking offenders, known as “Career Offenders,” at or near the statutory maximum penalty. Tracking statutory criteria, a defendant qualifies as a Career Offender in the sentencing guidelines if:

the defendant was at least 18 years of age at the time he or she committed the instant offense the instant offense is a felony that is a crime of violence or a controlled substance offense the defendant has at least two prior felony convictions of either a crime of violence or a controlled substance offense.

There were 75,836 federal criminal cases reported to the United States Sentencing Commission during fiscal year 2014. Of the 67,672 cases in which the Commission received complete guideline application information, 2,269 (3.4%) offenders were sentenced as career offenders. Offenders sentenced under the career offender guidelines over the past ten years have consistently accounted for about three percent of federal offenders sentenced each year.

While career offenders account for just 3% of the annual federal caseload, they account for more than 11% of the federal prison population due to their lengthy prison sentences (on average, more than 12 years, or 147 months, in prison).

Career offenders often receive sentences below the guideline range (often at the government’s request), especially when they qualify as career offenders on the basis of drug trafficking offenses alone (“drug trafficking only” pathway).

Although career offenders with a violent instant or prior offense often have more serious criminal histories, the career offender directive has the most significant impact on drug trafficking offenders because they often carry higher statutory maximum penalties than some violent offenses

Despite similar average guideline minimums, “drug trafficking only” career offenders are generally sentenced less severely than other career offenders. In these cases, federal judges impose sentences similar to the sentences recommended in the guidelines for the underlying drug trafficking offense.

While career offenders, as a group, tend to recidiviate at higher rates than non-career offenders, the United States Sentencing Commission found a lower recidivism rate among career offenders qualifying on the basis of drug trafficking offenses alone.

In addition to having a more serious and extensive criminal history, career offenders who have committed a violent offense recidivate at a higher rate and are more likely to commit another violent offense in the future (see the “violent only” and “mixed” groups in the table below).

|

Drug Trafficking |

Only Mixed |

Only Mixed |

|

|

Recidivism Rate: |

54.4% |

69.4% |

69.0% |

|

Median Time to Recidivism |

26 Months |

20 Months |

14 Months |

|

Most Serious Post-Release Event |

Trafficking |

Assault |

Robbery |

|

26.5% |

28.6% |

35.3% |

|

Table 1. U.S. Sentencing Commission’s Recidivism Study Cohort Followed for Eight Years

Offender Demographics & Offense Characteristics

In fiscal year 2014, Black offenders accounted for more than half (59.7%) of offenders sentenced under the career offender guideline, followed by White (21.6 %), Hispanic (16.0%), and Other races (2.7%). Nearly all offenders sentenced under the career offender guideline were male (97.5%) and U.S. citizens (97.7%). Their average age at sentencing was 38 years.

In 2014, nearly three-quarters (74.1%) of career offenders were convicted of a drug trafficking offense. The remaining offenders would have been sentenced for robbery (11.6%), unlawful receipt, possession, or transportation of firearms (5.4%), aggravated assault (1.6%), and drug offenses occurring near a protected location (1.6%). Other offense types constituted the remaining 5.8 percent.

- : Career Criminals is shared under a CC BY 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by LibreTexts.

: Criminal Gang Members

As the gang phenomenon has grown and spread in America’s cities and counties, there has been a parallel growth and spread of gangs in America’s prisons. There’s no way to know how many prisons gang member inmates have due, in part, to the fact that “Politics generally determine whether agencies [prisons] … admit to having STGs [Security Threat Groups like gangs].” It may also be impossible to gather accurate information on how many of America’s prisoners are involved in gang activity. However, judging from my own observations and other current research on the subject, one may safely say gangs and their members are prevalent in many prisons in the United States and elsewhere.

In some prisons, inmate gang members were members of gangs prior to their incarceration. They were arrested, incarcerated and, while incarcerated, continue to recruit and build their gang. Other gang members in prison had no gang affiliation prior to their imprisonment but joined one of the prison gangs many of which have counterparts on the streets. In other prisons, notably in California and Texas, gangs have formed which had no counterpart on the street. The gangs were created in prison. Examples of these gangs include the Mexican Mafia, Neta, Aryan Brotherhood, Black Guerrilla Family, La Nuestra Familia and the Texas Syndicate.

According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, On December 31, 2000, a total of 1,237,469 inmates were confined in state and federal prisons in the United States. A total of 232,900 of these inmates were between the ages of 18 and 24. Those youthful inmates, roughly of gang member age, represent approximately 18% of all the inmates.

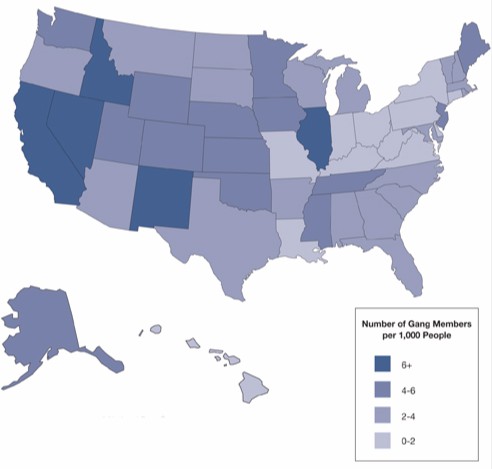

Figure 3.1 Image by: NGIC and NDIC 2010 National Drug Survey Data is in the public domain.

There are at least five major prison gangs, each with its own structure and purpose.

The Mexican Mafia (La Eme)

The Mexican mafia started at the Deuel Vocational Center in Tracy, California, in the 1950s and was California’s first prison gang composed primarily of Chicanos, or Mexican Americans. Entrance into La Eme requires a sponsoring member. Each recruit has to undergo a blood oath to prove his loyalty. The Mexican Mafia does not proscribe killing its members who do not follow instructions. Criminal activities include drug trafficking and conflict with other prison gangs, which is common with the Texas Syndicate, Mexikanemi, and the Aryan Brotherhood (AB).

The Aryan Brotherhood

The Aryan Brotherhood, a white supremacist group, was started in 1967 in California’s San Quentin prison by white inmates who wanted to oppose the racial threat of black and Hispanic inmates and/or counter the organization and activities of black and Hispanic gangs. Pelz, Marquart, and Pelz suggest that the AB held distorted perceptions of blacks and that many Aryans felt that black inmates were taking advantage of white inmates, especially sexually, thus promoting the need to form and/or join the Brotherhood. Joining the AB requires a 6-month probationary period. Initiation, or “making one’s bones,” requires killing someone. The AB traffics in drugs and has a blood in, blood out rule; natural death is the only nonviolent way out. The Aryan

Brotherhood committed eight homicides in 1984, or 32 percent of inmate homicides in the Texas correctional system, and later became known as the “mad dog” of Texas corrections.

The Aryan Brotherhood structure within the federal prison system used a three-member council of high-ranking members. Until recently, the federal branch of the Aryan Brotherhood was aligned with the California Aryan Brotherhood, but differences in opinion caused them to split into separate branches. The federal branch no longer cooperates with the Mexican Mafia in such areas as drugs and contract killing within prisons, but as of October 1997, the California branch still continued to associate with the Mexican Mafia. Rees suggested that the Aryan Brotherhood aligned with other supremacist organizations to strengthen its hold in prisons. The Aryan Brotherhood also has strong chapters on the streets, which allows criminal conduct inside and outside prisons to support each other.

Black Panther George Jackson united black groups such as the Black Liberation Army, Symbionese Liberation Army, and the Weatherman Underground Organization to form one large organization, the Black Guerrilla Family, which emerged in San Quentin in 1966. Leaning on a Marxist-Leninist philosophy, the Black Guerrilla Family was considered to be one of the more politically charged revolutionary gangs, which scared prison management and the public. Recently, offshoots within the Black Guerrilla Family have appeared. California reported the appearance of a related group known as the Black Mafia.

La Nuestra Familia

La Nuestra Familia (“our family”) was established in the 1960s in California’s Soledad prison, although some argue it began in the Deuel Vocational Center. The original members were Hispanic inmates from Northern California’s agricultural Central Valley who aligned to protect themselves from the Los Angeles-based Mexican Mafia. La Nuestra Familia has a formal structure and rules as well as a governing body known as La Mesa, or a board of directors. Today, La Nuestra Familia still wars against the Mexican Mafia over drug trafficking but the war seems to be easing in California.

The Texas Syndicate

The Texas Syndicate emerged in 1958 at Deuel Vocational Institute in California. It appeared at California’s Folsom Prison in the early 1970s and at San Quentin in 1976 because other gangs were harassing native Texans. Inmate members are generally Texas Mexican Americans, but now the Texas Syndicate offers membership to Latin Americans and perhaps Guamese as well. The Texas Syndicate opposes other Mexican American gangs, especially those from Los Angeles. Dominating the crime agenda is drug trafficking inside and outside prison and selling protection to inmates.

Like other prison gangs, the Texas Syndicate has a hierarchical structure with a president and vice president and an appointed chairman in each local area, either in a prison or in the community. The chairman watches over that area’s vice chairman, captain, lieutenant, sergeant at arms, and soldiers. Lower-ranking members perform the gang’s criminal activity. The gang’s officials, except for the president and vice president, become soldiers again if they are moved to a different prison, thus avoiding local-level group conflict. Proposals within the gang are voted on, with each member having one vote; the majority decision determines group behavior.

The Mexikanemi

The Mexikanemi (known also as the Texas Mexican Mafia) was established in 1984. Its name and symbols cause confusion with the Mexican Mafia. As the largest gang in the Texas prison system, it is emerging in the federal system as well and has been known to kill outside as will as inside prison. The Mexikanemi spars with the Mexican Mafia and the Texas Syndicate, although it has been said that the Mexikanemi and the Texas Syndicate are aligning themselves against the Mexican Mafia (Orlando-Morningstar, 1997). The Mexikanemi has a president, vice president, regional generals, lieutenants, sergeants, and soldiers. The ranking positions are elected by the group based on leadership skills. Members keep their positions unless they are reassigned to a new prison. The Mexikanemi has a 12-part constitution. For example, part five says that the sponsoring member is responsible for the person he sponsors; if necessary, a new person may be eliminated by his sponsor.

Hunt et al. suggest that the Nortenos and the Surenos are new Chicano gangs in California, along with the New Structure and the Border Brothers. The origins and alliances of these groups are unclear; however, the Border Brothers are comprised of Spanish- speaking Mexican American inmates and tend to remain solitary. Prison officials report that the Border Brothers seem to be gaining membership and control as more Mexican American inmates are convicted and imprisoned.

Crips and Bloods

The Crips and Bloods, traditional Los Angeles street gangs, are gaining strength in the prison as well as are the 415s, a group from the San Francisco area (415 is a San Francisco area code). The Federal Bureau of Prisons cites 14 other disruptive groups within

the federal system, which have been documented as of 1995, including the Texas Mafia, the Bull Dogs, and the Dirty White Boys. (Citations omitted to save space. You may view the original work which includes the omitted citations.)

If Beck’s 1991 estimate that approximately 12% of prison inmates were gang-affiliated could be extrapolated to today, then perhaps as many as 148,496 gang members (12% of all 1,237,469 inmates) were confined in state and federal prisons on December 31, 2000. If, in order to be a gang, at least five characteristics of a gang were required then as many as 74, 245 inmates were gang members (6% of all 1,237,469 inmates). According to the California Department of Corrections there are over 100,000 gang inmates in that state’s correctional facility.

A one-year study of over 82,000 federal inmates in the United States revealed that those who were embedded in gangs (referred to as gang embeddedness) were more likely to exhibit violent behavior and misconduct than those who were peripherally involved in gangs. And those who were peripherally involved exhibited more violent behavior and misconduct than those who were unaffiliated.

In gang-dominated prisons, gangs rule the roost. Which inmates eat at what times and where they sit in the dining hall, who gets the best or worst job assignments in the prison, who has money and nice clothes, who lives and who dies – all of these things, and others, are determined by gangs in the prison. Their very presence requires special attention from prison authorities.

Prison staff, too, may be participants in or potential victims of the prison gang culture. As participants, they may be actively or passively involved. As active participants they may collude with inmate gang members by providing alibis, providing opportunities for the commission of certain crimes, or taking bribes or payment for their silence or other form of assistance.

As passive participants in prison gang activity they may simply “overlook” an incident or situation or neglect their duty just long enough for the gang members to do what it is that they wanted to do. In either case, prison staff are not immune to the negative influence of prison gangs. As victims of gang activity, they may be threatened, harassed, extorted, physically or sexually assaulted, or murdered.

Approximately 600,000 inmates were released from American prisons in the year 2005. Some of them were die hard gang members. Upon being discharged from prison (when one’s full sentence has been served) or released early parole, prison gang members move back into society. Unless they recant their gang membership, they are likely to continue their gang activity. Their impact on a community may be measured by their continued criminal activity, the harm they inflict upon their victims and their participation in already existing community-based gangs.

Many inmates find it difficult to survive in prison unless they are affiliated with a gang. But there’s a twist. The twist may be best explained using an analogy. Do you remember a game called Rock, Scissors, Paper? It’s a game kids play using hand signs. Each player chooses rock, scissors, or paper without telling the other players their choice. Then each child displays their chosen hand sign at the same time. Rock is symbolized by a clenched fist and rock beats scissors. Scissors are characterized by a protruding index and middle finger in the shape of scissors blades and scissors beat paper. Paper is shown by holding out an open hand with fingers all touching side by side. If we stop the game there I can use this as an analogy that helps describe the gang situation in prison. In the analogy “rock” is race or ethnicity, “scissors” is a gang, and “paper” is an inmate who is not gang affiliated. Inmates who are not affiliated with a gang are often in peril in a prison setting. They have no one who will come to their aid if they are assaulted or extorted and no one who will join them in retaliation.

There are a few exceptions to this rule. The exceptions include inmates who have organized crime connections on the outside, and those who are knowledgeable about the law and may, therefore, be valued for their ability to help other inmates write legal briefs for their appeals. There are other inmates who are basically left alone because they are seriously ill or very old, and inmates who are so physically powerful or out of their minds that few inmates will assault them.

Most inmates, however, are vulnerable. In our analogy the next class of inmates are the gang members – scissors. They assault non- gang members – those who are “paper” in our analogy, and rival gang members. According to one federal prison administrator, “About one-third of my prison’s one thousand seven hundred inmates are not in a gang. They are referred to by the staff as ‘lame’ or as ‘dorks.‘ They eat meals together in the mess hall with the Native Americans. The unaffiliated are often extorted by gang inmates and used in other ways.”

Then there are the rocks – the racial and ethnic groups. They beat all. That is, African-American inmates who are Crips, Bloods, Black Gangster Disciples, or whatever their name, are faced with a new enemy – groups of non-African-Americans. In most instances this means they need protection from Caucasian, Asian, and Hispanic inmates in the prison. Suddenly prior gang affiliation and old hatreds between same-race/same-ethnicity gangs succumb to fears of racial or ethnic conflict.

- : Criminal Gang Members is shared under a CC BY 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by LibreTexts.

: Managing Gangs in a Prison Setting

Special administrative and management techniques have been developed to deal with the conflicts which arise out of a gang presence in a prison. One correctional administrator indicated “There is a heavy emphasis on gathering gang intelligence inside and outside the prison in an effort to maintain safety and security. The correctional facility has five Intelligence Officers within the correctional officer cadre, one for each gang – the Blacks, Latinos, Asians, Whites, and Latin Kings.” The administrative structure of the prison reflects its gang clientele.

Prison gangs constitute a persistently disruptive force in correctional facilities because they interfere with correctional programs, threaten the safety of inmates and staff, and erode institutional quality of life.

Prison gangs share organizational similarities. They have a structure with one person who is usually designated as the leader and who oversees a council of members that makes the gang’s final decisions. Like some street counterparts, prison gangs have a creed or motto, unique symbols of membership, and a constitution prescribing group behavior.

Prison gangs dominate the drug business, and many researchers argue prison gangs are also responsible for most prison violence. Adverse effects of gangs on prison quality of life have motivated correctional responses to crime, disorder, and rule violations, and many correctional agencies have developed policies to control prison gang-affiliated inmates.

The current policy of some prison administrators in their dealings with incarcerated gang members is to use both intervention and suppression strategies. Intervention initiatives are sometimes referred to as “de-ganging” or “renunciation programs” while some institutions segregate or separate gangs from one another in hopes of maintaining peace in the facility. The Taylorville Correctional Center in Illinois is an example of a prison which does not tolerate gang activity. According to the Illinois Department of Corrections:

The department designates Taylorville Correctional Center as a security threat group free prison. Admission to the facility requires inmates to have no documented history of security threat group membership or activity. Strong disciplinary sanctions are employed for any inmate identified as participating in any security threat group activity including transfer, loss of good time, disciplinary segregation and loss of privileges.

According to Meghan Mandeville, News Research Reporter for Corrections Connection, in order to “help inmates who want to break away from that way of life, TDCJ created the Gang Renouncement and Disassociation (GRAD) program to give them a way out.”It gives the offenders an avenue to renounce their gang membership, to get out of the gang and to be able to go back to the general population,” said Kenneth W. Lee, Program Administrator for TDCJ’s STG Management Office. “Then, [they can] be released into the free world and thrive in society.

Conditions of American prison contribute to the problems surrounding prison gangs and their members’ impact on the communities to which they return when paroled or released from prison. They state that:

We do not advocate coddling inmates, but we surely do not advocate allowing millions of imprisoned inmates to live with drug addictions, emotional difficulties, and educational and employment skills so poor that only minimum-wage employment awaits them. These are the disabilities that, to some degree define the American inmate population, and these same disabilities will damage the quality of life in our communities when these untreated, uneducated, and marginal inmates return home . . . Prisons are our last best chance to help law-breakers find a lawful, economically stable place in mainstream communities.

Suppression efforts include, among other things, isolation of gang members within the prison and reducing the influence of gang leaders by moving them to different prisons or centralizing them in one prison.

As all these gang-member inmates are released into their home communities, what will their impact be on local gang members? If the receiving communities don’t act to provide returning inmates with housing, job training, and jobs, I predict their newly achieved status as ex-convict will result in their being respected in the gang community. They will encourage cooperation with former enemy gangs in pursuit of greater gain and increased criminality.

As we’ve seen, gangs in prison, much like those on the street, are difficult to eliminate because they have come to serve a purpose – they are functional. They provide their members with protection, security, power, status, income, and association with others of their own kind. This does not bode well when it comes to integrating ex-convict gang members back into the community once they are released or paroled from confinement.

One can only guess, of course, about what the future holds in store as regards gangs in our prisons. It is certain that more gangs and gang members are appearing in prisons where, heretofore, they were seldom found. As of this writing, there are approximately

2,100,000 people confined in prisons and jails in the United States and that number has been growing steadily over the past two decades. Increasingly violent crimes committed by gang members, and the use of imprisonment and longer sentences to control them, suggest more gang members will fill our prisons’ cells in the future.

- : Managing Gangs in a Prison Setting is shared under a CC BY 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by LibreTexts.

: Accidental Criminals

Most people attempt to obey the law in their daily lives, but what happens when someone unintentionally commits a crime? A mistake or moment of not paying attention could lead to someone breaking the law without even realizing what they have done. Breaking the law, whether accidentally or intentionally, can lead to serious consequences if the person is found guilty, so it is important to understand the law.

Accident vs Intent

Mens Rea is a legal term that refers to the mental condition in which a person needs to be in to establish whether or not they committed a crime intentionally. A person that accidentally walks off with another person’s jacket in a public area will most likely have a very similar jacket themselves in the same location. The person lacking Mens Rea (criminal mind) would attempt to find the real owner of the jacket once they realize their mistake. By contrast, a person that takes a jacket that he has never seen before, puts it on and then leaves is most likely aware that it does not belong to him and had the criminal intent.

A parent pushing their crying baby through a department store may place items on the stroller with the intent to purchase the items. While tending to the child and attempting to pay for other items, they might forget about the items on the stroller and leave the store without paying for them. Once the parent realizes their mistake, if they are innocent they will most likely return the property to the store, thus throwing in doubt intent and lending credibility to it being an accident.

Sometimes minor crimes will be excused if the officer, prosecutor or judge determines them to be accidental, however there are some laws that end in prosecution regardless of the circumstances or intent. Driving under the influence of alcohol or a controlled substance is an example of Strict Liability. Strict Liability laws do not require criminal liability. Anyone committing the action can be arrested or prosecuted even if they did so unwittingly.

A man might decide to have two glasses of whiskey with dinner and then drive his car to take his date home, believing that he has only consumed a small amount of alcohol and will not be over the legal limit. However, the glasses of whiskey may have been larger than standard servings. A person found operating a vehicle while over the legal alcohol limit will always be prosecuted. Bartenders that unknowingly serve alcohol to minors are also liable to be prosecuted for their actions even if they did not intend to break the law.

An example of a strict-liability prosecution occurred in New Mexico in 1996, Bobby Unser, a three-time winner of the Indianapolis 500, went snowmobiling with a friend. A snowstorm blew in causing whiteout conditions, resulting in Unser and his friend becoming trapped. After two full days and nights, the men found a building with a phone, and called for help. Unser informed the

U.S. Forest Service of the incident and was prosecuted for entering a wilderness area even though there was no intent he planned to violate the law. Unser was convicted and fined by a United States Federal Court District Judge. The conviction was appealed and upheld by the Appellate Court.

- : Accidental Criminals is shared under a CC BY 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by LibreTexts.

: Elderly Criminals

An aging population in general coupled with mandatory sentencing laws has caused an explosion in the number. This is an expensive proposition for the American correctional system. A substantial reason for this increased cost is the increased medical attention people tend to require as they grow older. Prisons that rely on prison industry to subsidize the cost of operations find that elderly inmates are less able to work than their younger counterparts. There is also the fear that younger inmates will prey on elderly ones. This phenomenon has caused the federal prison system and many state systems to rethink the policies that contribute to this “graying” of correctional populations.

Substantial growth has also been seen in the number of inmates that are ill. Arthritis and hypertension are the most commonly reported chronic conditions among inmates, but more serious and less easily treated maladies are also common. Many larger jails and prisons have special sections devoted to inmates with medical problems. In addition to the normal security staff, these units must employ medical staff. Recruiting medical staff that are willing to work in confinement with inmates is a constant problem for administrators.

According to many critics of mental health in America, the number of mentally ill inmates has reached crisis level. There has been explosive growth in the incarceration of mentally ill persons since the deinstitutionalization movement of the 1960s. As well- meaning people advocated for the rights of American’s mentally ill, they fostered in a sinister unintended consequence: As mental hospitals closed, America’s jails became the dumping ground for America’s mentally ill population. This problem was exacerbated at the federal level by the passage of the Community Mental Health Act of 1963, which substantially reduced funding of mental health hospitals. With state hospitals gone or severely restricted, communities had to deal with the issue of what to do with mentally ill persons. Most communities responded with the poor solution of criminalizing the mentally ill.

- : Elderly Criminals is shared under a CC BY 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by LibreTexts.