13 4: Alternatives to Incarceration

Key Terms:

Split Sentence John Augustus Active Supervision

Intensive Probation (ISP) Boot Camp

Revocation Absconders Morrissey vs. Brewer Restorative Justice

Probation Intermediate Sanctions Inactive Supervision

Work Release Programs Parole

Technical Violation Halfway Houses Gagnon vs. Scarpelli Drug Courts

- : Probation

- : Officer Roles

- : Intermediate Sanctions

- : Parole

- : Treatment

- : Halfway Houses

- : Home Confinement/Electronic Home Monitoring

- : Fines and Restitution

- : Community Service

- : Sex Offender Treatment and Civil Commitment

- : Mental Health Courts

- : Restorative Justice

- : Boot Camp

- : Public Shaming

- : Drug Courts

: Probation

Probation is very similar to parole, and many of the legal issues are identical. Many jurisdictions combine the job of probation and parole officer, and these officers are often employed in departments of community corrections. The most basic difference between probation and parole is that probationers are sentenced to community sanctions rather than a prison sentence. Parolees have already served at least some prison time. Some jurisdictions can sentence an offender to a split sentence. A split sentence requires the offender to stay in prison for a short time before being released on probation.

Most criminal justice historians trace the roots of modern probation to John Augustus, who began his professional life as a businessperson and boot maker. Augustus became known as the father of probation largely due to his strong belief in abstinence from alcohol. He was an active member in the Washington Total Abstinence Society, an organization that believed criminals motivated by alcohol could be rehabilitated by human kindness and moral teachings rather than incarceration. His work began in earnest when, in 1841, he showed up in a Boston police court to bail out a “common drunkard.” Augustus accompanied the man on his court date three weeks later, and those present were stunned at the change in the man. He was sober and well kempt. For 18 years, he served in the capacity of a probation officer on a purely voluntary basis. Shortly after his death in 1859, a probation statute was passed so that his work could continue under the auspices of the state. With the rise of psychology’s influence in the 1920s, probation officers moved from practical help in the field to a more therapeutic model. The pendulum swung back to a more practical bent in the 1960s when probation officers began to act more as service brokers. They assisted probationers with such things as obtaining employment, obtaining housing, managing finances, and getting an education.

Many jurisdictions have several levels of supervision. The most common distinction between levels of probationers is active supervision and inactive supervision. Probationers on active supervision are required to report in with a probation officer at regular intervals. Probationers can be placed on inactive supervision because they committed only minor offenses. Serious offenders can sometimes be placed on inactive supervision when they have completed much of a long probation sentence without problems.

The preferred method of checking in depends on the jurisdiction. Many require in person visits, but some jurisdictions allow phone calls and checking in via mail. Inactive probationers are not required to check in at all or very infrequently. Checking in with an officer is a condition of probation. Other conditions often include participation in treatment programs, paying fines, and not using drugs or alcohol. If these conditions are not followed, the the probationer is said to be a violator. Violators are subject to probation revocation. Revocations often result in a prison sentence, but some violators are given second chances, and some are sentenced to special programs for technical violations. Many jurisdictions classify absconders differently than other violators. An absconder is a probationer (or parolee) that stops reporting and “disappears.”

Following the trend of mass incarceration in the United States over the past several decades has been a similar trend in what has been called “mass community supervision.” In 1980, about 1.34 million offenders were on probation or parole in the United States. That figure exploded to nearly 5 million by 2012. The Bureau of Justice Statistics (Maruschak & Parks, 2014) provides a look at these numbers from a different vantage point: about 1 in 50 adults in the United States were under community supervision at yearend 2012. The community supervision population includes adults on probation, parole, or any other post-prison supervision.

- : Probation is shared under a CC BY 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by LibreTexts.

: Officer Roles

Many jurisdictions combine the role of probation officer and parole officer into a single job description. In Gagnon v. Scarpelli (1973), the court had this to say of the duties of the such officers: “While the parole or probation officer recognizes his double duty to the welfare of his clients and to the safety of the general community, by and large concern for the client dominates his professional attitude. The parole agent ordinarily defines his role as representing his client’s best interests as long as these do not constitute a threat to public safety.” This statement suggests a dichotomy in the responsibility of parole (and probation) officers; these must look out for the best interest of the client as well as looking out for the best interest of the public. This fact frequently enters into politics. Liberals tend to focus on the treatment and rehabilitation of the offender, and conservatives focus more on the safety of the public and just deserts for the offender.

Note

Pin It! Gagnon v. Scarpelli Case Study

Is a previously sentenced probationer entitled to a hearing when his probation is revoked? Gagnon v. Scarpelli decides this question

From the perspective of the parole officers, they must perform law enforcement duties that are designed to protect the public safety. These functions very much resemble the tasks of police officers. They are also officers of the court and are responsible for enforcing court orders. These orders often include such things as drug testing programs, drug treatment programs, alcohol treatment programs, and anger management programs.

Officers are often required to appear in court and give testimony regarding the activities of their clients. They frequently perform searches and seize evidence of criminal activity or technical violations. The courts often ask officers to make recommendations when violations do occur. Officers may recommend that violators be sent to prison or continue on probation or parole with modified conditions.

There is ambivalence about the role of probation and parole officers within the criminal justice community. This has to do with an artificial dichotomy, often being characterized as police work versus social work. The detection and punishment of law and technical violations are characterized as the law enforcement role. The rehabilitation and reintegration of the offender are regarded as the social work role. Officers tend to lean more heavily toward one of these objectives than the other. Some officers embrace the law enforcement perspective and seek strict compliance with the law and conditions of parole. Other officers view themselves more as counselors, helping the offender reform, and brokering community resources to help resolve problems. Which model a particular officer exemplifies has many influences. The officer’s personal beliefs, the dominate culture of the local office, the policy dictates of agency heads, and legislative enactments driven by political philosophies all play a role in shaping the working personality of each officer. The most effective officers are likely to be hybrids that fall somewhere in between the two archetypes.

- : Officer Roles is shared under a CC BY 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by LibreTexts.

: Intermediate Sanctions

Traditionally, a person convicted of an offense was sentenced to probation or sentenced to prison. There was no middle ground. The purpose of intermediate sanctions is to seek that middle ground by providing a punishment that is more severe than probation alone, yet less severe that a period of incarceration. Perhaps the most common among these alternatives is Intensive Supervision Probation (ISP). Offenders given to this sort of intermediate sanction are assigned to an officer with a reduced caseload. Caseloads are reduced in order to provide the officer with more time to supervise each individual probationer. Frequent surveillance and frequent drug testing characterize most ISP programs. Offenders are usually chosen for these programs because they have been judged to be at a high risk for reoffending.

Another common type of alternative to prison is the work release program. These programs are designed to maintain environmental control over offenders while allowing them to remain in the workforce. Most often, offenders sentenced to a work release program reside in a work release center, which can be operated by a county jail, or be part of the state prison system. Either way, work- release center residents are allowed to leave confinement for work related purposes. Otherwise, they are locked in a secure facility.

Correctional boot camps are facilities run along similar lines to military boot camps. Military style discipline and structure along with rigorous physical training are the hallmarks of these programs. Usually, relatively young and nonviolent offenders are sentenced to terms ranging from three to six months in boot camps. Research has found that convicts view boot camps as more punitive than prison and would prefer prison sentence to being sent to boot camp. Research has also shown that boot camp programs are no more effective at reducing long-term recidivism than other sanctions.

- : Intermediate Sanctions is shared under a CC BY 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by LibreTexts.

: Parole

The practice of releasing prisoners on parole before the end of their sentences has become an integral part of the correctional system in the United States. Parole is a variation on imprisonment of convicted criminals. Its purpose is to help individuals reintegrate into society as constructive individuals as soon as they are able, without being confined for the full term of the sentence imposed by the courts. It also serves to lessen the costs to society of keeping an individual in prison. The essence of parole is release from prison, before the completion of sentence, on the condition that parolees abide by certain rules during the balance of the sentence. Under some systems, parole is granted automatically after the service of a certain portion of a prison term. Under others, parole is granted by the discretionary action of a board, which evaluates an array of information about a prisoner and makes a prediction whether he is ready to reintegrate into society.

To accomplish the purpose of parole, those who are allowed to leave prison early are subjected to specified conditions for the duration of their parole. These conditions of parole restrict their activities substantially beyond the ordinary restrictions imposed by law on an individual citizen. Typically, parolees are forbidden to use alcohol and other intoxicants or to have associations or correspondence with certain categories of undesirable persons (such as felons). Typically, also they must seek permission from their parole officers before engaging in specified activities, such as changing employment or housing arrangements, marrying, acquiring or operating a motor vehicle, traveling outside the community, and incurring substantial indebtedness. Additionally, parolees must regularly report to their parole officer.

Note

Parole Conditions-California State

All inmates released from a California State prison who are subject to a period of State parole supervision will have conditions of parole that must be followed. Some parolees will have imposed special conditions of parole which must also be followed. Special conditions of parole are related to the commitment offense and/or criminal history and will discourage criminal behavior, improving the parolee’s chances for success on parole.

Conditions of Parole and Special Conditions of Parole are defined as:

Conditions of Parole – the general written rules you must follow.

Special Conditions of Parole – these are special rules imposed in addition to the general conditions of parole and must also be followed. They are related to your commitment offense and/or criminal history and may be imposed by the Board of Parole Hearings, by the court, or by your parole agent.

General Conditions of Parole:

Your Notice and Conditions of Parole will give the date that you are released from prison and the maximum length of time you may be on parole.

You, your residence (where you live or stay) and your possessions can be searched at any time of the day or night, with or without a warrant, and with or without a reason, by any parole agent or police officer.

You must waive extradition if you are found outside of the state.

You must report to your parole agent within one day of your release from prison or jail. You must always give your parole agent the address where you live and work.

You must give your parole agent your new address before you move.

You must notify your parole agent within three days if the location of your job changes, or if you get a new job. You must report to your parole agent whenever you are told to report, or a warrant can be issued for your arrest. You must follow all of your parole agent’s verbal and written instructions.

You must ask your parole agent for permission to travel more than 50 miles from your residence and you must have your parole agent’s approval before you travel.

You must ask for and get a travel pass from your parole agent before you leave the county for more than two days. You must ask for and get a travel pass from your parole agent before you can leave the State, and you must carry your travel pass on your person at all times.

You must obey ALL laws.

If you break the law, you can be arrested and incarcerated in a county jail even if you do not have any new criminal charges.

You must notify your parole agent immediately if you get arrested or get a ticket.

The parole officers are part of the administrative system designed to assist parolees and to offer them guidance. The conditions of parole serve a dual purpose; they prohibit, either absolutely or conditionally, behavior that is deemed dangerous to the restoration of the individual into normal society. Moreover, through the requirement of reporting to the parole officer and seeking guidance and permission before doing many things, the officer is provided with information about the parolee and an opportunity to advise him. The combination puts the parole officer into the position in which he can try to guide the parolee into constructive development.

The enforcement advantage that supports the parole conditions derives from the authority to return the parolee to prison to serve out the balance of his sentence if he fails to abide by the rules. In practice, not every violation of a parole condition will automatically lead to a revocation. Typically, a parolee will be counseled to abide by the conditions of parole, and the parole officer ordinarily does not take steps to have parole revoked unless he thinks that the violations are serious and continuing so as to indicate that the parolee is not adjusting properly and cannot be counted on to avoid antisocial activity. The broad discretion accorded the parole officer is also inherent in some of the quite vague conditions, such as the typical requirement that the parolee avoid “undesirable” associations or correspondence. Yet revocation of parole is not an unusual phenomenon, affecting only a few parolees. According to the Supreme Court in Morrissey v. Brewer, 35% – 45% of all parolees are subjected to revocation and return to prison. Sometimes revocation occurs when the parolee is accused of another crime; it is often preferred to a new prosecution because of the procedural ease of recommitting the individual on the basis of a lesser showing by the State.

Note

Pin It! Morrissey v. Brewer Case Study

Does a parolee have the right to defend himself if he breaks parole? Morrisey v. Brewer settles this issue.

- : Parole is shared under a CC BY 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by LibreTexts.

: Treatment

An “alternative to incarceration” is any kind of punishment other than time in prison or jail that can be given to a person who commits a crime. Frequently, punishments other than prison or jail time place serious demands on offenders and provide them with intensive court and community supervision. Just because a certain punishment does not involve time in prison or jail does not mean it is “soft on crime” or a “slap on the wrist.” Alternatives to incarceration can repair harms suffered by victims, provide benefits to the community, treat the drug-addicted or mentally ill, and rehabilitate offenders. Alternatives can also reduce prison and jail costs and prevent additional crimes in the future. Before we can maximize the benefits of alternatives to incarceration, however, we must repeal mandatory minimums and give courts the power to use cost-effective, recidivism-reducing sentencing options instead.

- : Treatment is shared under a CC BY 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by LibreTexts.

: Halfway Houses

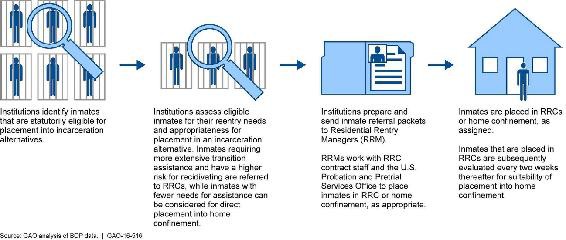

Halfway houses (also called “community correction centers” or “residential reentry centers” by the federal Bureau of Prisons) are used mostly as an intermediate housing option to help a person return from prison to the community after he has served a prison sentence. Sometimes, though, halfway houses can be used instead of prison or jail, usually when a person’s sentence is very short. For example, halfway houses may be a good choice when a person has served time in prison, been released on parole, and then violated a parole condition and been ordered to serve a few months additional time for that violation. While in halfway houses, offenders are monitored and must fulfill conditions placed on them by the court. Usually, offenders must remain inside the halfway house except when they are going to court or to a job.

Figure 4.1 Bureau of Prisons’ Process for Placing Inmates into Residential Reentry Centers (RRC) and Home Confinement. Image is in the public domain.

- : Halfway Houses is shared under a CC BY 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by LibreTexts.

: Home Confinement/Electronic Home Monitoring

Home confinement (also called “house arrest”) requires offenders to stay in their homes except when they are in certain pre- approved areas (i.e., at court or work). Often, home confinement requires that the offender be placed on electronic home monitoring (EHM). EHM requires offenders to wear an electronic device, such as an ankle bracelet, that sends a signal to a transmitter and lets the authorities know where the offender is at all times. Like probation, home confinement usually comes with conditions. If the offender violates those conditions, he can be put in jail or prison. Offenders on EHM usually contact a probation officer daily and take frequent and random drug tests. In many jurisdictions, an offender cannot be placed on EHM unless the court or a jail official recommends it.

- : Home Confinement/Electronic Home Monitoring is shared under a CC BY 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by LibreTexts.

: Fines and Restitution

Requiring the offender to pay supervision fees, fines, and court costs can be used as an independent punishment or in addition to other punishments. “Tariff fines” are a set amount applied to every offender when a particular crime is committed (e.g., $500 for driving while intoxicated), regardless of the offender’s income level or ability to pay. For the wealthy, tariff fines can be too small to be a meaningful punishment. For the poor, tariff fines can be too large, resulting in jail time when the offender cannot pay. “Day fines” are one solution. They are not a flat amount but are based on the seriousness of the crime and the offender’s daily income. Wealthier offenders pay more and pay an amount that is a meaningful loss of income, while those with lower incomes pay an amount they can afford and avoid jail. Restitution requires offenders to pay for some or all of a community or victim’s medical costs or property loss that resulted from the crime.

- : Fines and Restitution is shared under a CC BY 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by LibreTexts.

: Community Service

Community service can be its own punishment or can act as a condition of probation or an alternative to paying restitution or a fine (each hour of service reduces the fine or restitution by a particular amount, until it is paid in full). Community service is unpaid work by an offender for a civic or nonprofit organization. In federal courts, community service is not a sentence, but a special condition of probation or supervised release.

Figure 4.2 File: Community Service Work Detail for 35th District Court Northville Michigan.JPG. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license.

- : Community Service is shared under a CC BY 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by LibreTexts.

: Sex Offender Treatment and Civil Commitment

Many sex offenders are placed on probation, with requirements that they attend a sex offender treatment program, report regularly to a probation officer, do not contact their victims, do not use the internet, and do not live or work in certain areas. Sex offender treatment programs can be inpatient (residential) or outpatient (non-residential) and generally use cognitive-behavioral therapy, counseling, and other approaches to reduce the likelihood that the person will commit another sex offense. About 20 states also have “civil commitment” programs, which place sex offenders in secure hospitals or residential treatment facilities for treatment. These offenders typically receive civil commitment only after they have finished serving a prison term for their sex offense. Offenders can be required to stay on civil commitment indefinitely, which means the programs can cost up to four times what it costs to keep an offender in prison.

- : Sex Offender Treatment and Civil Commitment is shared under a CC BY 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by LibreTexts.

: Mental Health Courts

Mental health courts, like drug courts, are specialized courts that place offenders suffering from mental illness, mental disabilities, drug dependency, or serious personality disorders in a court-supervised, community-based mental health treatment program. Court and community supervision are combined with inpatient or outpatient professional mental health treatment. Offenders receive rewards for compliance with supervision conditions and are disciplined for noncompliance. They are also linked to housing, health care, and life skills training resources that help prevent relapse and promote their recovery. Often, offenders must first plead guilty to charges before being diverted to mental health court.

- : Mental Health Courts is shared under a CC BY 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by LibreTexts.

: Restorative Justice

Restorative justice is a holistic sentencing process focused on repairing harm and bringing healing to all those who are impacted by a crime, including the offender. Representatives of the justice system, victims, offenders, and community members are involved and achieve these goals through sentencing circles, victim restitution, victim-offender mediation, and formalized community service programs. Sentencing circles occur when the victim, offender, community members, and criminal justice officials meet and jointly agree on a sentence that repairs the harm the offender caused. Victim-offender mediation allows the offender and victim to meet and exchange apologies and forgiveness for the crime committed. Restorative justice practices can be used alone or as a condition of a sentence of probation.

- : Restorative Justice is shared under a CC BY 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by LibreTexts.

: Boot Camp

Boot camp programs involve intense daily regimens that include physical exercise, individual counseling, educational classes, and studying for a GED. Today, boot camps are no longer used in the federal prison system and are rarely used in state corrections systems. Like a military boot camp, offenders follow a strict disciplinary code that requires them to wear short hair and uniforms, stand at attention before their officers, and address their superiors as “sir.” Offenders who complete the program and find a job can become eligible for early release. Once released, they may be put on probation.

- : Boot Camp is shared under a CC BY 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by LibreTexts.

: Public Shaming

Public shaming is public humiliation. It is used rarely and usually only for low-level misdemeanors. For example, a court ordered a convicted mail thief to stand outside a post office for a total of 100 hours wearing a sign that said, “I am a mail thief. This is my punishment.” Public shaming is intended to rehabilitate the offender and discourage him from re-offending.

- : Public Shaming is shared under a CC BY 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by LibreTexts.

: Drug Courts

Drug courts are a special branch of courts created within already-existing court systems. Drug courts provide court-supervised drug treatment and community supervision to offenders with substance abuse problems. All 50 states and the District of Columbia have at least a few drug court programs. There are no drug courts in the federal system. Some states have drug courts for adults and for juveniles, as well as family treatment or family dependency treatment courts that treat parents so that they might remain or reunite with their children.

Drug court eligibility requirements and program components vary from one locality to another, but they typically require some or all of the following:

Require offenders to complete random urine tests, attend drug treatment counseling or Narcotics Anonymous/Alcoholics Anonymous meetings, meet with a probation officer, and report to the court regularly on their progress;

Require offenders to complete random urine tests, attend drug treatment counseling or Narcotics Anonymous/Alcoholics Anonymous meetings, meet with a probation officer, and report to the court regularly on their progress;

Give the court authority to praise and reward the offender for successes and discipline the offender for failures (including sending the offender to jail or prison);

Give the court authority to praise and reward the offender for successes and discipline the offender for failures (including sending the offender to jail or prison);

Are available to non-violent, substance-abusing offenders who meet specific eligibility requirements (e.g., no history of violence, few or no prior convictions);

Are available to non-violent, substance-abusing offenders who meet specific eligibility requirements (e.g., no history of violence, few or no prior convictions);

Are not available on demand – usually, either the prosecutor or the judge handling the case must refer the offender to drug court; sometimes, this referral can only be made after the offender pleads guilty to the offense; and

Are not available on demand – usually, either the prosecutor or the judge handling the case must refer the offender to drug court; sometimes, this referral can only be made after the offender pleads guilty to the offense; and

Allow offenders who successfully complete the program to avoid pleading guilty, having a conviction placed on their record, or serving some or all of their prison or jail time; some programs also allow successful participants who have already pled guilty to have their drug conviction removed from their record.

Allow offenders who successfully complete the program to avoid pleading guilty, having a conviction placed on their record, or serving some or all of their prison or jail time; some programs also allow successful participants who have already pled guilty to have their drug conviction removed from their record.

4.15: Drug Courts is shared under a CC BY 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by LibreTexts.