16 7: Innovative Programs in Correctional Facilities

Key Terms:

|

Aging without Bars |

Re-entry programs |

|

Barriers to success |

Elements of successful re-entry |

|

Female programs |

Pre-release programs |

|

Clients not criminals |

Risk-Needs-Responsivity (RNR) |

|

Evidence-based rehabilitation |

Logic-model |

- : Aging Without Bars

- : Washington D.C Court Supervision and Offender Release Program

- : Virginia Department of Corrections

- : Common Factors of Successful Prison and Reentry Programs

- : Barriers to Success

- : Female Prisoners

- : California Rehabilitative Reform

In this Chapter, we explore new prison programs designed to improve inmates’ skills to improve their transition back into the community. The shift towards rehabilitation and skills training has proven successful in the reduction of recidivism rates.

This page titled 7: Innovative Programs in Correctional Facilities is shared under a CC BY 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by Dave Wymore & Tabitha Raber.

: Aging Without Bars

Aging Without Bars is a six-week person-centered training that helps inmates age 50 and older prepare to transition to the community. It addresses inmates’ lack of awareness of available resources by providing education and connecting them to case management services prior to their release, when possible. The program is implemented through a collaboration of Area Agencies on Aging (AAA) and jail intake staff, as well as community partners. The AAA became engaged in this area after the 2008-2012 Virginia 4-Year Plan for Aging Services ranked the older prisoner population as among the top areas of concern.

Measuring impact is a priority of this program. There is a pre-test and a post-test follow-up with each participant to assess what they have learned and to help calibrate the person’s needs moving forward. Evaluation of the program indicates that improvements have occurred across each of the performance measures: housing and economic stability, mental and physical health, and social supports. Inmates have shared that this is a life-changing program for them and have commented that they feel less invisible and forgotten as a result of their participation.

- : Aging Without Bars is shared under a CC BY 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by LibreTexts.

: Washington D.C Court Supervision and Offender Release Program

Washington, DC Office on Aging the DC Court Supervision and Offender Release Program and the Washington, DC Office on Aging (the AAA) partnered to address older inmate reentry needs related to employment and housing. The program began several years ago as an ad hoc effort in response to tremendous demand to assist older offenders with reentry. The DC Office on Aging conducted comprehensive pre-screening of mental and physical health status of the participants in order to develop customized plans and partnered to provide job skills training and coaching. The program has now transitioned from the DC Office on Aging to the DC Office of Employment Services, so it can be integrated with other training and skills development programs such as the Senior Community Service Employment Program, the workforce program within the Older Americans Act.

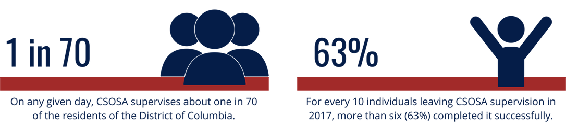

Figure 7.1 CSOSA achieves high successful completion rates as a result of the combination of supports and close supervision and accountability strategies, including partnerships with local law enforcement partners. Image is in the Public Domain.

Because of the program, approximately 80 percent of participants were employed within a six-month period of reentry. Word-of- mouth has continued to increase enrollment. Families reach out proactively to the program to help pave the way when their loved one is released from prison, providing evidence that the community sees the value of this program. Challenges the program works to overcome include bringing participants’ job skills up to date, ensuring participants have photo identification, addressing needs of individuals who did not enter the country legally, and addressing mental health and substance abuse issues.

- : Washington D.C Court Supervision and Offender Release Program is shared under a CC BY 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by LibreTexts.

: Virginia Department of Corrections

The Virginia Department of Corrections and the Virginia Department for Aging and Rehabilitative Services have embarked on a project to offer Chronic Disease Self-Management Education (CDSME) workshops for the aging prisoner population and other offenders living with chronic health conditions. Between 1990 and 2013 in Virginia, the prison population over the age of 50 increased from 822 individuals to 6,709 individuals. The state found that inmates were becoming older, sicker and staying longer behind bars. The program, now known as “Live Well Virginia!” was first introduced to the prison population at Bland Correction Center by District Three Senior Services AAA with the goal of helping Virginia offenders pursue a healthier lifestyle while incarcerated by teaching participants chronic disease self-management strategies and information on weight management, healthy eating, physical activity, rational decision making and relaxation. The program found that a secondary benefit of the program is the interaction and mutual support that the workshop fosters between prisoners. Building upon the success of CDSME at this site, Senior Connections (the AAA in in Richmond, VA) also began offering CDSME at a prison in its service area.

Figure 7.2 Virginia Department of corrections seal. Image in the Public Domain.

Since the workshops began, 37 workshops have been held in five correctional centers from south west to north central Virginia. Approximately 479 offenders have attended these sessions, with 368 inmates completing the workshops (a 77 percent retention rate). The Virginia Department of Corrections Director Harold Clark has stated, “This program helps offenders with chronic conditions take charge of their own well-being, contributing to better health outcomes while they’re incarcerated and successful reentry into their communities when they’re released.” A participant in the program stated, “The lessons you all have taught me will last a lifetime.” Based on the program’s early success, the effort was expanded to other prisons through partnership with additional AAAs.

- : Virginia Department of Corrections is shared under a CC BY 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by LibreTexts.

: Common Factors of Successful Prison and Reentry Programs

The poll and follow-up interviews reveal opportunities for engaging AAAs in supporting older inmates or those being released in the near future. The most important factor contributing to a successful initiative is a relationship between the AAA and the criminal justice system, whether it is a relationship with the local jail or prison in the AAA service area, a relationship with the local parole or probation department, or a contact at the state Department of Corrections. In instances where the jail or prison was not receptive to a partnership, implementing services in the jail or prison ultimately proved unrealistic. In many instances, partners in the criminal justice system (jail, prison, parole, probation, etc.) have recognized the limitations of the services they are able to provide and welcomed the partnership.

An additional predictor of a successful program is when the AAA and correctional system partner are housed within the same county, city government or Council of Governments structure. Having these departments housed under one institution facilitates coordination and communication. For example, the Schuyler County Office on Aging in New York is located in proximity to the probation and parole departments, as both are part of county government.

In Arlington, Virginia, the AAA and the local jail are also part of the same county government structure. Finally, securing buy-in from both staff and community members is essential. Programs benefit from staff who are willing to learn about the needs of older prisoners, and, at times, expand work scopes to accommodate a new initiative. In general, AAAs reported being pleased with support from the community to provide services to older prisoners and recently released individuals and shared that securing this support is another significant contributor to success.

Three Elements to Successful Reentry Programs for Inmates

- Start early

Until recently, the focus of organizations and government agencies has been predominantly on release programs, while ignoring the significance of pre-release programs. The Federal Bureau of Prisons philosophy states, “release preparation begins the first day of incarceration, and focus on release preparation intensifies at least 18 months prior to release.”

Successful reentry programs for inmates rely on more than just helping ex-offenders find jobs; it also requires helping offenders change their attitudes and beliefs about crime, addressing mental health issues, offering educational opportunities and job training, providing mentoring, and connecting them with community resources. Consideration should be given to providing most, if not all, of these things before a person’s release date.

- Clients, not criminals

When some government agencies and social service organizations see “offenders”, they can present a one-size fits all approach that ends up fitting no one. However, the Council for State Governments Justice Center suggests that employment programs need to move beyond traditional services. Instead, they recommend addressing individuals’ underlying attitudes about crime and work, making them more likely to succeed at getting and keeping jobs and less likely to reoffend. Not all offenders share the same levels of risk and learning how to accurately assess these attributes and deliver customized help is an important element to truly helping people get out of the criminal justice system.

- Evaluate frameworks

According to the Manpower Demonstration Research Corporation, an organization that works to help improve the lives of low- income people, “There is a growing consensus that reentry strategies should build on a framework known as Risk-Needs- Responsivity (RNR).” The framework helps organizations assess individuals’ risk levels for recidivism and provide appropriate levels of response.

Models like Hawaii’s Operation “HOPE” aim to change how we look at probation and post-incarceration monitoring. Since more than half of recidivism is a result of technical violations of parole, this is an important part of the reentry process to examine. By trying new methods, tracking efforts and outcomes, the desire is to move towards a system of reentry programs for inmates that serve their function while minimizing negative side effects.

- : Common Factors of Successful Prison and Reentry Programs is shared under a CC BY 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by LibreTexts.

: Barriers to Success

Some of the challenges in serving the prison population are the same that affect the Area Agencies on Aging’s (AAA) ability to serve the broader aging community. Lack of funding and staff resources are pervasive challenges for AAAs, no matter the population served. As the aging population has continued to grow, 75 percent of AAA budgets have remained flat or decreased over the last two years. AAAs find it difficult to expand programming to address the needs of new populations while existing programs, such as nutrition, transportation, case management and caregiver programs, are already stretched to the limit. For AAAs serving the older prisoner population, there is often more demand than they can handle, resulting in a need to triage their efforts and develop partnerships when possible.

AAAs would benefit from having efficient and effective tools to track aging prisoner program information to demonstrate the impact of their services. For CDSME programs, having data on how the program improves health outcomes (measuring weight, blood pressure and cholesterol) would be beneficial. For reentry programs, having data on the correlation between connecting recently released individuals to necessary services (such as transportation, housing and employment) and the impact on recidivism, would substantiate the need for these programs. Having the systems in place to track outcomes would underscore the importance of the AAA interventions and may serve to enhance collaboration with the correctional system. While tracking outcomes is important, it has also been necessary for AAAs to establish metrics prior to beginning a program to make the case and secure buy-in from key stakeholders. Some AAAs have struggled to secure data from prison and jail partners, such as the numbers of prisoners who plan to return home to the AAA service area after their discharge.

Some AAAs have found challenges with engaging the correctional system in these programs. While some correctional facilities have been very receptive to partnerships and see the value in providing aging-related services in jails or prisons, others have been reluctant to partner with external organizations. Further education on the unique needs and challenges faced by the aging prison population with criminal justice stakeholders would be beneficial.

An additional challenge that AAAs face in serving this population is overcoming established biases toward this demographic. When core programs are already stretched, stakeholders may question whether inmates or recently released individuals are as deserving of support as those who have not been convicted of crimes. On the other hand, some aging prisoners may have a bias against “the system” and have reservations about using a government-funded program when they feel that the system has not always served their best interests. One example of this type of bias can be seen in the DC reentry program, which was focused on employment. As part of the assessment to ensure clients are matched with the most appropriate resources, questions about mental health and addiction are raised. The DC program found that individuals did not always feel comfortable disclosing this type of information, resulting in employment placements that did not align with the needs or abilities of the individual being served.

- : Barriers to Success is shared under a CC BY 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by LibreTexts.

: Female Prisoners

Incarcerated women pose is significant difference from incarcerated men. The primary concern is that often times, women are the prime caretaker for children. When they are incarcerated, who cares for the children left behind? This may mean the children must be cared for by the father or extended family members, but this is not always possible, and the children may end up in foster care. To compound this problem, there are fewer female prisons, so they are farther away from their children making visits difficult if not impossible. These issues can have significant impact on the growth and development for the children and women. It can also make the reunification problem difficult.

Another issue for female prisoners is they may be pregnant or have other significant medical issues during incarceration. What happens to the child upon delivery is a significant concern for incarcerated females. They may be unsure of long-term care for the newborn or how to cope with the separation immediately after birth. This can contribute to significant psychological issues for the female prisoner and could affect behavior and treatment.

More and more institutions are recognizing these concerns for female prisoners and started unique programs to address these issues. For example, the State of California has developed the Community Prisoner Mother Program:

The Community Prisoner Mother Program (CPMP) is a community substance abuse treatment program where non-serious, nonviolent female offenders may serve a sentence up to six years. The CPMP has been in existence since 1985 and is mandated by Penal Code (PC) Section 3410. Women are placed in the program from any of the female institutions. Pursuant to PC 3410, program eligibility requires that the female offender have up to two children less than six years of age, have no active felony holds, nor any prior escapes. The female offender must sign a voluntary placement agreement to enter the program, followed by three years of parole. The CPMP facilities are not the property of CDCR, and a private contractor provides program services at our Pomona facility. The treatment program addresses substance issues, emotional functioning, self-esteem, parenting skills, and employment skills.

Figure 7.3 Female Inmate Education Class. Photo by CoreCivic. Image is under a CC.By 2.0 license.

Basic Program Components of the CPMP

Pregnant and/or parenting mothers and their children under six years of age are provided programs and support services to assist in developing the skills necessary to become a functioning, self-sufficient family that positively contributes to society.

Pregnant and/or parenting mothers and their children under six years of age are provided programs and support services to assist in developing the skills necessary to become a functioning, self-sufficient family that positively contributes to society.

Individual Treatment Plans are developed for both the mother and child to foster development and personal growth. Program services focus on trauma-informed substance abuse prevention, parenting and educational skills.

Individual Treatment Plans are developed for both the mother and child to foster development and personal growth. Program services focus on trauma-informed substance abuse prevention, parenting and educational skills.

The program provides a safe, stable, and stimulating environment for both the mother and the child, utilizing the least restrictive alternative to incarceration consistent with the needs for public safety.

The program provides a safe, stable, and stimulating environment for both the mother and the child, utilizing the least restrictive alternative to incarceration consistent with the needs for public safety.

Program goals facilitate the mother/child bond, reunite the family, enhance community reintegration, foster successful independent living, and enhance self-reliance and self-esteem. The resultant mission is to break the inter-generational chain of crime and social services dependency.

Program goals facilitate the mother/child bond, reunite the family, enhance community reintegration, foster successful independent living, and enhance self-reliance and self-esteem. The resultant mission is to break the inter-generational chain of crime and social services dependency.

The primary focus of the CPMP is to reunite mothers with their child(ren) and re-integrate them back into society as productive citizens by (a) providing a safe, stable, wholesome and stimulating environment, (b) establishing stability in the parent-child

relationship and providing the opportunity for in-mate mothers to bond with their children and strengthen the family unit. Specific goals are:

- To PROMOTE community reintegration, independent living and self-reliance;

- To REDUCE the use of alcohol and drugs, involvement in criminal behavior, the rate of recidivism, Factors which result in trauma to children of incarcerated parents and ultimately long-term costs to the state;

- To INCREASE parenting skills, emotional stability, and educational and vocational opportunities;

- To ADDRESS substance abuse issues, behavioral and psychological factors which impact emotional stability, self-esteem, self- reliance, parent-child relationship and appropriate child development;

- To PROVIDE pre-release planning, employment skills, educational, vocational and parenting skills. (CDCR Website)

7.6: Female Prisoners is shared under a CC BY 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by LibreTexts.

: California Rehabilitative Reform

In 2004, the State of California began a massive reorganization of their prison system. California was suffering from massive prison overcrowding and there was massive pressure from both inside the system and from the Court. After decades of incapacitation, the Department of Corrections shifted its focus to rehabilitation. However, this time it was going to be measurable and effective by offering evidence-based treatment programs designed to reduce recidivism. Recidivism – returning offenders to custody after a violation or commission of a crime – was one of the biggest factors in the rising prison population. Prisons had become a revolving door with about 43% of released offenders being returned to custody within three years. Something had to change.

One of the first things the California Department of Corrections (CDC) did was to change their name to California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR). This change was to identify their focus was moving to not just incarceration but to focus on rehabilitation. Their mission was to return to the community offenders who could become productive and valuable members of the community. They did this by overhauling their system, adding education programs, job training, effective substance abuse treatment programs, cognitive behavior programs, and re-entry programs to improve the outcomes upon release. Massive overhaul of the California Youth Authority also occurred during this time. (To be discussed in Chapter 8).

California Enacts Major Change with Division of Addiction and Recovery Services (DARS)

Two significant events occurred between May and September 2007. In May 2007, Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger signed landmark legislation, the Public Safety and Offender Rehabilitation Services Act of 2007 (AB 900). This statute fundamentally changes California’s correctional system by focusing on rehabilitative programming for offenders as a direct way to improve public safety upon return of inmates to their communities. In September 2007, the Undersecretary of Adult Programs was 5 appointed, overseeing the DARS, Education and Vocation; Community Partnerships; Correctional Health Care Services; Victim & Survivor Rights and Services; and Prison Industry Authority.

Assembly Bill (AB) 900 is a major effort to reform California’s prison system by reducing prison overcrowding and increasing rehabilitative programming. DARS has responsibility for two of thirteen benchmarks established by AB 900 that must be met prior to the release of funds for construction projects outlined in the bill.

They are:

- At least 2,000 substance abuse treatment slots have been established with aftercare in the community. (The bill requires a total of 4,000 new in-prison substance abuse treatment slots with aftercare in the community overall), and

- Prison institutional drug treatment slots have averaged at least 75 percent participation over the previous six months.

DARS met the benchmark to add 2,000 in-prison substance abuse slots with aftercare in the community on December 30, 2008. At that point, all of the new programs were operational, and inmates were participating in treatment. DARS added approximately 55,000 square feet of new programming space to five institutions and one community correctional facility. In addition, between April 2007 and December 2008, the Department expanded community care participation by 2,960 treatment slots. This is a 119 percent growth in community care participation from 2,498 in April 2007 to 5,458 participants in December 2008.

In March 1, 2009, DARS began piloting the Interim Computerized Attendance Tracking System (ICATS) at Solano and Folsom State Prisons to monitor in-prison substance abuse program utilization. This system will be implemented at all in-prison substance abuse programs to ensure that substance abuse treatment program utilization is captured and sustained at 75 percent or above. In June 2007, the Expert Panel recommended the California Logic Model as this state’s approach to integrating evidence-based principles into its rehabilitation programming. (See Appendix A, page 60). The Governor’s Rehabilitation Strike Team provided guidelines on how to implement the Expert Panel recommendations.

DARS has been challenged to provide quality evidence-based rehabilitative treatment programs aligned with the California Logic Model. This rehabilitation programming implements programs based on inmate risk to recidivate and assessment of individual needs that will better prepare offenders for successful community reentry and reintegration. The Correctional Offender Management Profiling for Alternative Sanctions (COMPAS) and CDCR’s Addiction Severity Index (ASI) assessment tools will guide CDCR in placing the right offender in the right program at the right time.

DARS is continuing to develop programs that address the substance use disorder needs of its inmate population. Today, DARS delivers a redesigned program model that is trauma-informed, gender-responsive and includes standards and measures. In addition to the current modified Therapeutic Community, Cognitive Behavioral 6 Treatment and Psycho-Educational Treatment models are

being included to better address the needs of offenders. Currently, DARS manages more than 12,000 substance abuse treatment slots in 44 programs at 21 institutions. In addition, as of the June 30, 2008, 5,503 parolees participated daily in community-based Substance Abuse Treatment, or “continuing care” programs, throughout the State. DARS achieved major milestones in CDCR’s mission to strengthen substance abuse recovery programs, to reduce recidivism, and to increase public safety.

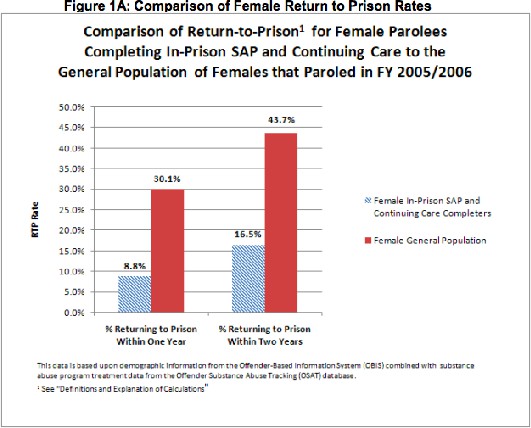

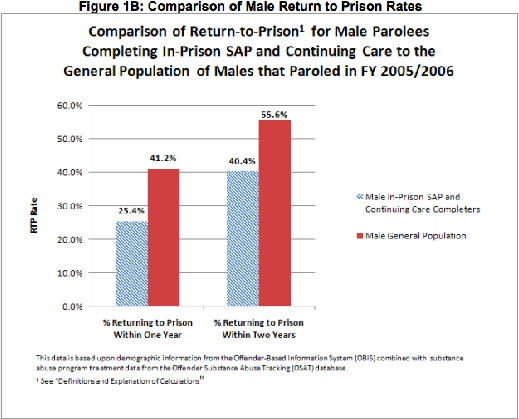

Return-to-prison rates are significantly reduced for offenders completing in-prison and community-based substance abuse treatment programs

The utility of corrections-based treatment for substance abusing offenders has spurred both research and debate this decade. The Prison Journal contains reports on the nation’s three largest prison-based treatment studies. These studies, being conducted in California, Delaware, and Texas, offer further evidence that substance abuse treatment for appropriate correctional populations can work when adequate attention is given to engagement, motivation, and aftercare. 1 Corrections-based treatment policy should emphasize a continuum of care model (from institution to community) with high quality programs and services. 2 1 (Simpson, D.D., Wexler, H.K., & Inciardi, J.A. (Eds.) (September/December, 1999). Special issue on drug treatment outcomes for correctional settings, parts 1 & 2. The Prison Journal, 79 (3/4). 2 (Hiller, M. L., Knight, K., & Simpson, D. D. (1999). Prison-based substance abuse treatment, residential aftercare and recidivism. Addiction, 94(6), 833-842. DARS’ multi-year commitment to linking inmates who have completed in-prison substance abuse programs with community-based substance abuse treatment programs is proving to be a successful combination. The most recent data which followed offenders who paroled in 2005-06 for a one-year and a two-year period demonstrates that the recidivism rate was reduced for offenders who completed in-prison substance abuse treatment programs – with a more substantial reduction in recidivism for offenders completing in-prison followed by community-based substance abuse treatment programs.

Recidivism, or return-to-prison, is defined as a paroled offender returning to prison for any reason during a specified time period. This includes offenders who are returned to Substance-Abuse Treatment-Control Units in correctional facilities; returned pending a revocation hearing by the Board of Parole Hearings on charges of violating the conditions of parole; returned to custody for parole violations to serve revocation time; or returned to custody by a court for a new felony conviction.

Figure 7.3 Demonstrated a lower return-to-prison rate for female offenders who completed both in-prison and community-based substance abuse treatment in Fiscal Year (FY) 2005-06 (8.8 percent after one year and 16.5 percent after two years) as compared to the return-to-prison rate for all CDCR female offenders (30.1 percent after one year and 43.7 after two years).

Figure 7.4 Demonstrated a lower return-to-prison rate for male offenders who completed both in-prison and community-based substance abuse treatment in FY 2005-06 (25.4 percent after one year and 40.4 percent after two years) as compared to the return- to-prison rate for all CDCR male offenders (41.2 percent after one year and 55.6 percent after two years).

EVIDENCE-BASED REHABILITATION REFORMS

Implemented historic evidence-based rehabilitation reforms

During FY 2007-08, DARS also played a major role in historic reforms to bring evidence-based rehabilitation to California’s correctional system. These reforms use evidence-based rehabilitation – academic, vocational, substance abuse and other programs – to help offenders succeed when they return to their communities and reduce the State’s recidivism rate. The major principles of evidence-based programs include: research-based risk and needs assessments, targeting of criminogenic needs, skills-oriented, responsivity to an individual’s unique characteristics, program intensity (dosage), continuity of care, and ongoing monitoring and evaluation. To integrate these evidence-based principles, DARS:

Demonstrated that the national research which states that in-prison substance abuse treatment followed by community-based aftercare reduces recidivism.

Demonstrated that the national research which states that in-prison substance abuse treatment followed by community-based aftercare reduces recidivism.

Integrated evidence-based treatment services in DARS’ treatment model. DARS solicited input for its treatment model from experts in the field including the CDCR Expert Panel, the DARS Treatment Advisory Committee and outside evaluators. This treatment design now includes Cognitive Behavioral Treatment and Psycho-Educational Interventions as well as the modified Therapeutic Community model. DARS in-prison substance abuse provider contracts now include the requirement that programs offer all of these models. Also included in this expanded treatment model is individualized treatment planning based on risk and needs assessment from COMPAS as an initial screening tool and the ASI as a secondary assessment instrument.

Integrated evidence-based treatment services in DARS’ treatment model. DARS solicited input for its treatment model from experts in the field including the CDCR Expert Panel, the DARS Treatment Advisory Committee and outside evaluators. This treatment design now includes Cognitive Behavioral Treatment and Psycho-Educational Interventions as well as the modified Therapeutic Community model. DARS in-prison substance abuse provider contracts now include the requirement that programs offer all of these models. Also included in this expanded treatment model is individualized treatment planning based on risk and needs assessment from COMPAS as an initial screening tool and the ASI as a secondary assessment instrument.

Implemented recommendations in “The Master Plan for Female Offenders: A Blueprint for Gender-Responsive Rehabilitation 2008” from the Division of Adult Institutions’ Female Offender Programs and Services (FOPS) office, and national experts including Barbara Bloom, Ph.D., Stephanie Covington, Ph.D., Barbara Owen, Ph.D., Nena Messina, Ph.D. and Christine Grella, Ph.D. These recommendations have informed CDCR’s approach to providing Gender Responsive and Trauma-Informed Treatment for female offenders.

Implemented recommendations in “The Master Plan for Female Offenders: A Blueprint for Gender-Responsive Rehabilitation 2008” from the Division of Adult Institutions’ Female Offender Programs and Services (FOPS) office, and national experts including Barbara Bloom, Ph.D., Stephanie Covington, Ph.D., Barbara Owen, Ph.D., Nena Messina, Ph.D. and Christine Grella, Ph.D. These recommendations have informed CDCR’s approach to providing Gender Responsive and Trauma-Informed Treatment for female offenders.

Opened the first-of-its-kind Trauma-Informed Gender-Responsive substance abuse treatment program for female offenders at Leo Chesney Community Correctional Facility. This program was implemented in collaboration with CDCR’s FOPS Division. This evidence-based model will be included in all AB 900 slots being added at Central California Women’s Facility and Valley State Prison for Women.

Opened the first-of-its-kind Trauma-Informed Gender-Responsive substance abuse treatment program for female offenders at Leo Chesney Community Correctional Facility. This program was implemented in collaboration with CDCR’s FOPS Division. This evidence-based model will be included in all AB 900 slots being added at Central California Women’s Facility and Valley State Prison for Women.

Participated in launching a pilot project at California State Prison, Solano, to implement and assess the effectiveness of DARS’ expanded treatment model, which includes science-based risk and needs assessment tools, risk-needs responsive treatment services and integrated treatment services. Placement of inmates is based on their risk to reoffend and their need for rehabilitative programs. CDCR is initially targeting offenders with a moderate to high risk to reoffend for placement in intensive rehabilitation programs that include substance abuse, vocation and education, anger management, and criminal thinking.

Participated in launching a pilot project at California State Prison, Solano, to implement and assess the effectiveness of DARS’ expanded treatment model, which includes science-based risk and needs assessment tools, risk-needs responsive treatment services and integrated treatment services. Placement of inmates is based on their risk to reoffend and their need for rehabilitative programs. CDCR is initially targeting offenders with a moderate to high risk to reoffend for placement in intensive rehabilitation programs that include substance abuse, vocation and education, anger management, and criminal thinking.

New Evidence-Based Rehabilitation Treatment Model

The goal of evidence-based rehabilitation is to reduce recidivism by implementing the five principles of effective intervention: Risk Principle: Target high-risk offenders

Need Principle: Treat risk factors associated with offending behavior Treatment Principle: Employ evidence-based treatment approaches Responsivity Principle: Tailor treatments to meet special needs

Fidelity Principle: Monitor implementation, quality, and treatment fidelity

Substance Abuse Programs represent one of several core offender rehabilitation program areas that also include: Education; Vocation; Criminal Thinking, Behaviors and Associations; and Anger, Hostility and Violence Management. Integrated service delivery fosters rehabilitation by incorporating various types of treatment that correspond to each individual’s unique needs, instead of a standard set of services. Practitioners within the fields of education, vocation, substance abuse treatment, and mental health will collaborate to design individualized treatment plans and analyze and monitor the overall impact of all treatment services for each individual.

All in-prison adult programs are being aligned with the California Logic Model.

The California Logic Model is a detailed, sequential description of how California will apply evidence-based principles and practices and effectively deliver a core set of rehabilitation programs. Research shows that to achieve positive outcomes, correctional agencies must provide rehabilitative programs to the right inmate at the right time and in a manner consistent with evidence-based programming design. The Logic Model includes the following eight components:

- Assess High Risk

- Assess Needs

- Develop Behavior Management Plan

- Deliver Programs

- Measure Progress

- Prep for Re-entry

- Reintegrate

- Follow-Up.

DARS provides coordinated services for inmates and parolees by working with partners in statewide law enforcement, health, and social services communities. It provides broad-based substance abuse treatment programs in correctional facilities that include transitional programs preparing inmates for release on parole, and community-based substance abuse treatment programs. Community-based organizations and state and local governmental agencies are assisting DARS in carrying out its mission. Community-based substance abuse treatment contractors provide most of the services for DARS inmates and parolee offender participants.

7.7: California Rehabilitative Reform is shared under a not declared license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by LibreTexts.