17 8: Juvenile Corrections

Key Terms:

|

State vs. Local Detention |

Dependent vs. Ward |

|

Status offender |

Delinquency Code |

|

Dual Status |

Juvenile Constitutional Protections |

|

Foster Care |

Specialized Care |

|

Arresting juveniles |

Detention |

|

Boot Camps |

Impact of institutionalization |

- : Juvenile Detention

- : Federal Juvenile Delinquency Code

- : Constitutional Protections Afforded Juveniles

- : Arresting Juveniles

- : Status Offender

- : Dual Status / Dependency vs Delinquency

- : Foster Home Placement

- : Special care placement

: Juvenile Detention

Many jails temporarily detain juveniles pending transfer to juvenile authorities.

Recent research by the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (OJJDP) shows that the trend in juvenile incarceration is toward lower numbers and a move toward local facilities. The juvenile offender population dropped 14% from 2010 to 2012, to the lowest number since 1975. In the March 2015 report, it was noted that for the first time since 2000, more offenders were in local facilities than were in state operated facilities.

The degree of security present in juvenile facilities tends to vary widely between jurisdictions. An important measure of security used in OJJDP reports is locking youth in “sleeping rooms.” Recent data indicates that public agencies are far more likely to lock juveniles in their sleeping quarters at least some of the time. A majority of state agencies (61%) reported engaging in this practice, while only a relatively small number (11%) of private agencies reported this practice. More than half of all facilities reported that they had one or more confinement features in addition to locking juveniles in their sleeping room (which usually happens at night). These security features usually consist of locked doors and gates designed to keep juveniles within the facility.

Unlike adult jails, juvenile detention takes place in a variety of different environments. According to the OJJDP study, the most common type of facility were facilities that considered themselves to be “residential treatment centers,” followed by those that considered themselves to be “detention centers.” The classifications of “group home,” “training school,” “shelter,” “wilderness camp,” and “diagnostic center” are also used. Group homes and shelters tended to be privately owned, and detention centers tended to be state run facilities.

Figure 8.1. Camp Erwin Owen, located in Kernville, California, was founded in 1938. This non-secure juvenile forestry camp houses 125 wards between the ages of 14 and 18 committed by the Juvenile Court. Camp Erwin Owen by Tabitha Raber is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

Federal Level

Nearly two-thirds of all youth arrested are referred to a court with juvenile jurisdiction for further processing. Juvenile Offenders and Victims: A National Report, National Center for Juvenile Justice (August, 1995). Cases that progress through the system may result in adjudication and court-ordered supervision or out-of-home placement or may result in transfer for criminal (adult) prosecution. Id. Over the five-year period from 1988 through 1992, the juvenile courts saw a disproportional increase in violent offense cases and weapon law violations. Id.

Many gang members and other violent offenders are under the age of eighteen when they commit criminal acts. Therefore, under 18 U.S.C.A. § 5031, these offenders are classified as “juveniles” for purposes of federal prosecution. Federal crimes committed by the juveniles which would be crimes if committed by an adult or violations of 18 U.S.C.A. § 922(x) are classified as acts of “juvenile delinquency.” Gang members are treated as adults for federal criminal prosecutions if they have attained their eighteenth birthday when they commit federal crimes.

At common law, one accused of a crime was treated essentially the same whether he was an infant or an adult. It was presumed that a person under the age of seven could not entertain criminal intent and thus was incapable of committing a crime. [Allen v. United States, 150 U.S. 551, 14 S. Ct. 196, 37 L. Ed. 1179 (1893).] One between the ages of seven and fourteen was presumed incapable

of entertaining criminal intent but such presumption was rebuttable. Id. A person fourteen years of age and older was prima facie capable of committing crime. Id.

Prior to 1938, there was no federal legislation providing for special treatment for juveniles. In 1938, the Federal Juvenile Delinquency Act was passed with the essential purpose of keeping juveniles apart from adult criminals. The original legislation provided juveniles with certain important rights including the right not to be sentenced to a term beyond the age of twenty-one. This early law also provided that an individual could be prosecuted as a juvenile delinquent only if the Attorney General in his discretion so directed. The 1938 Act gave the Attorney General the option to proceed against juvenile offenders as adults or as delinquents except with regard to those allegedly committing offenses punishable by death or life imprisonment. The Juvenile Delinquency Act was amended in 1948, with few substantive changes.

In 1974, Congress adopted the Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act (hereinafter referred to as “the Act”). Its stated purpose was “to provide basic procedural rights for juveniles who came under federal jurisdiction and to bring federal procedures up to the standards set by various model acts, many state codes and court decisions”. (S. Rep. No. 1011, 93 Cong., 2d Sess., reprinted in 1974 U.S.C.C.A.N. 5283, 5284.) The purpose of the Act is to remove juveniles from the ordinary criminal process to avoid the stigma of a prior criminal conviction and to encourage treatment and rehabilitation. [United States v. One Juvenile Male, 40 F.3d 841, 844 (6th Cir. 1994).] This purpose, however, must be balanced against the need to protect the public from violent offenders. Id. The intent of federal laws concerning juveniles are to help ensure that state and local authorities would deal with juvenile offenders whenever possible, keeping juveniles away from the less appropriate federal channels since Congress’ desire to channel juveniles into state and local treatment programs is clearly intended in the legislative history of 18 U.S.C.A. § 5032. [United States v. Juvenile Male, 864 F. 2d 641, 644 (9th Cir. 1988).] Referral to the state courts should always be observed except in the most severe of cases. [United States v. Juvenile, 599 F. Supp. 1126, 1130 (D. Or. 1984).]

Title 21, United States Code, Section 860, provides enhanced criminal penalties for those who illegally distribute, possess with intent to distribute, or manufacture a controlled substance in or on, or within 1,000 feet of, the real property comprising a public or private elementary, vocational, or secondary school or a public or private college, junior college, or university, or a playground, or housing facility owned by a public housing authority, or within 100 feet of a public or private youth center, public swimming pool, or video arcade facility. The statute also provides a mandatory minimum imprisonment term of not less than one year for violators. [21 U.S.C.A. § 860(a) (West Supp. 1995).] There are additional enhancements for repeat offenders. [21 U.S.C.A. § 860(b) (West Supp. 1995).]

It is a federal offense to possess a firearm in a school zone. 18 U.S.C.A. § 922(g) (West Supp. 1995). However, the Supreme Court ruled the Gun-Free School Zone Act was unconstitutional as exceeding Congress’ commerce clause authority in [United States v. Lopez, U.S. , 115 S.Ct. 1624, L. Ed.2d (1995).] Prior to this decision, Congress amended Section 922(g) by expressly stating in the statute the national need to regulate firearms around schools and its nexus to commerce. [18 U.S.C.A. § 922(g)(1) (West Supp. 1995).] Whether this change will accommodate the ruling made the basis for the Lopez decision is yet to be finally determined.

- : Juvenile Detention is shared under a CC BY 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by LibreTexts.

: Federal Juvenile Delinquency Code

The Federal Government often provides guidance and foundation on governance for the states. They provide the guidelines for how to will manage certain processes and then allow the states to determine what best suits their unique populace. States are allowed to create laws, ordinances, and judicial practices as long as they do not violate a citizen’s Constitutional rights. Juvenile processes and procedures are no different than many other areas in the criminal justice system where the Federal Government provides guidance with allowance for adjustments. In this section, we examine the Federal Juvenile Delinquency Code.

Before prosecuting juvenile delinquent conduct, a thorough reading of Chapter 403 of Title 18, United States Code (18 U.S.C.A. §§ 5031-42), should be made. This chapter, codified from the Act, applies to any individual who commits a federal criminal violation prior to his eighteenth birthday. The Act applies to illegal aliens as well as to American citizens. United States v. Doe, 701 F. 2d 819, 822 (9th Cir. 1983). The United States Attorneys’ Manual, Title 9-8.000, provides some guidance on prosecuting those committing acts of juvenile delinquency.

Some terms need to be understood when referring to the Act. “Juvenile delinquency” means a federal criminal violation committed prior to one’s eighteenth birthday. “Juvenile” means a person who has not attained his eighteenth birthday, or for the purpose of proceedings and disposition under the Act for an alleged act of juvenile delinquency, one who has not attained his twenty-first birthday. “Certification”|B250 is the document filed by the United States Attorney which confirms to the court that delinquency proceedings in federal court are authorized.

A person who commits a crime while aged eighteen or older may not be tried under the Act but must be proceeded against as an adult. [United States v. Smith, 675 F. Supp. 307, 312 (E.D.N.C. 1987).] A person older than twenty-one may, in some situations, be proceeded against as an adult for committing an act of juvenile delinquency. A defendant who commits an act of juvenile delinquency but is not indicted until after he turns twenty-one years of age, is not entitled to protection of the Act and must be prosecuted as an adult. [United States v. Hoo, 825 F. 2d 667, 670 (2d Cir. 1987), cert. denied, 484 U.S. 1035, 108 S. Ct. 742, 98 L. Ed. 2d 777 (1988).] The defendant may have a good objection to an adult charge filed after he turns twenty-one for a prior act of juvenile delinquency, if the delay in prosecuting him causes him substantial prejudice and is an intentional device to gain a tactical advantage. [Id. At 671, citing United States v. Marion, 404 U.S. 307, 92 S. Ct. 455, 30 L. Ed. 2D 468 (1971).]

The Act imparts considerable prosecutorial discretion as to whether an accused will be tried as an adult even though the criminal conduct charged qualifies as an act of juvenile delinquency. [United States v. Welch, 15 F. 3d 1202, 1207 (1st Cir.), cert. Denied, U.S., 114 S. Ct. 1863, 128 L. Ed. 2d 485 (1994).] The government may bring a motion to transfer|B251 a juvenile defendant to the district court for prosecution as an adult if the juvenile is at least fifteen years of age and the government alleges that the juvenile committed certain enumerated transferrable offenses (e.g., violent crimes or controlled substance violations). [18 U.S.C.A. § 5032 (West Supp. 1995); Welch, 15 F. 3d at 1208.] The government may also implement the mandatory transfer|B253 of a juvenile offender who has previously committed certain crimes.

- : Federal Juvenile Delinquency Code is shared under a CC BY 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by LibreTexts.

: Constitutional Protections Afforded Juveniles

The United States Supreme Court has held that in juvenile commitment proceedings, juvenile courts must afford to juvenile’s basic constitutional protections, such as advance notice of the charges, the right to counsel, the right to confront and cross-examine adverse witnesses, and the right to remain silent. [In re Gault, 387 U.S. 1, 87 S. Ct. 1428, 18 L. Ed. 2d 527 (1967).] The Supreme Court has extended the search and seizure protections of the Fourth Amendment to juveniles. [New Jersey v. T.L.O., 469 U.S. 325, 333, 105 S. Ct. 733, 738, 83 L. Ed. 2d 720 (1985).] It has also been held that the Fourth Amendment requires that a juvenile arrested without a warrant be provided a probable cause hearing. [Moss v. Weaver, 525 F. 2d 1258, 1259-60 (5th Cir. 1976).] The exclusionary rule also applies to federal delinquency adjudications. [United States v. Doe, 801 F. Supp. 1562, 1567-72 (E.D. Tex. 1992).]

Juveniles are entitled to Fifth Amendment protection against self-incrimination in juvenile proceedings despite the non-criminal nature of those proceedings. [In re Gault, 387 U.S. at 49-50, 87 S. Ct. at 1455-56.] Substance, not form, controls in determining the applicability of the Fifth Amendment to proceedings not labeled criminal. Id. at 49-50, 87 S. Ct. at 1455-56. Since a juvenile defendant’s liberty is at stake, the Fifth Amendment applies.

Juveniles are not, however, accorded the full panoply of rights that adult criminal defendants are accorded, such as the right to trial by jury. [McKeiver v. Pennsylvania, 403 U.S. 528, 91 S. Ct. 1976, 29 L. Ed. 2d 647 (1971).] Most of the opinions reason that a jury trial is not required because the Act does not treat alleged juvenile delinquents as alleged criminals, and therefore, the Constitution does not mandate it.

Figure 8.2 Juvenile Justice Center in Kern County. JJC by Tabitha Raber is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

The McKeiver court stated that, “(t)here is a possibility, at least, that the jury trial, if required…, will remake the juvenile proceeding into a fully adversary process and will put an effective end to what has been the idealistic prospect of an intimate, informal protective proceeding.” [403 U.S. at 545, 91 S. Ct. at 1986.] As a result, juvenile courts still process juvenile delinquents in a manner more paternal and diagnostic than that afforded their adult criminal counterparts. [Alexander S. by and through Bowers

v. Boyd, 876 F. Supp. 773, 781 (D.S.C. 1995).]

A juvenile is accorded all due process rights at a juvenile hearing which includes the right to contest the value of the evidence offered by the government. [Kent v. United States, 383 U.S. 541, 563, 86 S. Ct. 1045, 1058, 16 L. Ed. 2d 84 (1966).] Although juvenile adjudications are adjudications of status rather than criminal liability, the government must still prove beyond a reasonable doubt that a juvenile is a delinquent. [In re Winship, 397 U.S. 358, 90 S. Ct. 1068, 25 L. Ed. 2d 368 (1970).]

Proceedings for adjudication of a juvenile as a delinquent shall be in district court. [18 U.S.C.A. § 5032 (West Supp. 1995).] The court may convene at any time and place within the district, in chambers or otherwise, to take up the proceedings of juvenile delinquency. A juvenile may consent to having a magistrate judge preside over cases involving a Class B or C misdemeanor, or an infraction. [18 U.S.C.A. § 3401(g) (West Supp. 1995).] There is a certain advantage to the juvenile in exercising this option since a magistrate judge cannot impose a term of imprisonment in these situations. Id. Proceedings in misdemeanor cases can be ordered to be conducted before a district judge rather than a magistrate judge by the court’s own motion or upon petition with good cause by the United States Attorney. [18 U.S.C.A. § 3401(f) (West 1985).]

- : Constitutional Protections Afforded Juveniles is shared under a CC BY 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by LibreTexts.

: Arresting Juveniles

Whenever a juvenile is arrested for an act of juvenile delinquency, he must immediately be advised of his legal rights. [18 U.S.C.A.

§ 5033 (West 1985).] The Attorney General (United States Attorney) shall be notified. Id. The juvenile’s parents, guardian or custodian must also be immediately notified of his arrest as well as his rights and of the nature of the alleged offense. This requirement is not invoked when a juvenile is arrested and placed into administrative detention, but rather is initiated by the juvenile’s placement into custody after the filing of an information alleging delinquent conduct. [United States v. Juvenile Male, 74 F.3d 526, 530 (4th Cir. 1996).] Notification made after a statement has been given or made without spelling out the juvenile’s right to notify a responsible adult cannot satisfy the statutory mandate. [United States v. Nash, 620 F. Supp. 1439, 1442-43 (S.D.N.Y. 1985).]

Figure 8.3 USMS-Omaha-2 by the Omaha Police Department.is used under a CC BY 2.0 license.

If the juvenile is an alien, a reasonable effort must be made to reach his parents, and if not feasible, prompt notice to his country’s Consulate should be made. [United States v. Doe, 862 F. 2d 776, 780 (9th Cir. 1988).]

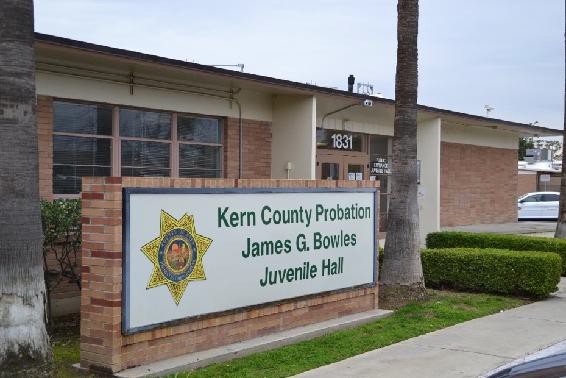

Figure 8.4 James G. Bowles Juvenile Hall is operated 24 hours a day, 365 days a year by the Kern County Probation Department as a secure detention facility for minors. JGB Juvenile Hall by Tabitha Raber is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

Regarding cases of juvenile delinquency, the United States Attorney can proceed in different ways. The case can be referred to state authorities, attempts to adjudicate the juvenile as a delinquent can be made, or the United States Attorney can move to transfer the juvenile for criminal prosecution as an adult.

- : Arresting Juveniles is shared under a CC BY 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by LibreTexts.

: Status Offender

When we look at juvenile crime and detention, we must look at several issues surrounding the unique nature of the juvenile offender. First, we must differentiate between crimes and status offenses. Most times when a juvenile is arrested, it is thought they must have committed a crime. However, juveniles historically could be detained (incarcerated) for “status” offenses. These are “crimes” that only juveniles can be arrested for such as curfew violations, truancy or being “incorrigible,” basically not listening to your parent. These petty infractions could get a juvenile locked in a detention facility without even a hearing. Today, this no longer happens, and our guidelines have changed in regard to these offenses. However, it is important to know the history and the reason behind the practice. While status offenses are not serious, they are often precursor to more delinquent behavior.

Figure 8.5 Groundbreaking on Future Detention Home in Richmond Virginia, Dated June 14, 1956. Image is under a CC.By 2.0 license.

The Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (OJJDP) recognized this as a significant issue pertaining to juvenile and provided research into the concern in the following abstract:

Scope of the Problem Status Offending behavior is often a sign of underlying personal, familial, community, and systemic issues, similar to the risk factors that underlie general offending. Sometimes these underlying issues contribute to delinquency later in life, putting youths at a higher risk for drug use, victimization, engagement in risky behavior, and overall increased potential for physical and mental health issues, including addiction (Greenwood and Turner 2011; Chuang and Wells 2010; Buffington, Dierkhising, and Marsh 2010; Henry, Knight, and Thornberry 2012; Mersky, Topitzes, and Reynolds 2012). Ample evidence supports the notion that less serious forms of delinquency often precede the onset of more serious delinquent acts (Huizinga, Loeber, and Thornberry 1995; Elliott, 1994). However, the “precursor to delinquency” view of status offending does not take into account the normal experimentation of childhood and adolescence or the diverse developmental pathways that can lead to serious delinquency (Kelley et al. 1997). Children and adolescents commonly experiment with behaviors that are not considered positive or prosocial, such as lying, being truant, or defying parents. Such experimentation allows youths to discover the negative consequences of their behaviors and learn from their mistakes. Most youths who engage in status and other minor offenses never progress to more serious behaviors (Kelley et al. 1997). States have formulated differing approaches to defining and handling status offenders. The approaches can be broadly divided into three categories: status offenders as delinquents, status offenders as neglected/abused dependents, or status offenders as a separate legislative category. The classification of offense behaviors largely dictates the kind of treatment and services that status offenders are likely to receive. The legal definition of a status offense is critical, as it can impact the treatment and availability of services to a youth in the juvenile justice system (Kendall 2007). Relatively few states define status offenses as delinquent behavior under statute, yet many status offenders end up being treated as de facto delinquents. One such way is through the use of probation as a disposition for status offenders, which is an option in 30 states (Szymanski 2006). Often, status offenders will be placed on probation, only to be later incarcerated as the result of a technical violation, regardless of whether the status offense was serious enough to initially warrant the use of confinement (Yeide and Cohen 2009).

Impact of Institutionalization: Research is limited with regard to the specific impacts of institutionalization on particular subgroups, such as status offenders. However, researchers have examined the general impact of institutionalization on juvenile offenders and consistently demonstrated that confinement in correctional facilities does not reduce reoffending and may increase it for certain youths (e.g., Lipsey and Cullen 2007). In some cases, status offenders are placed in the same facilities as juveniles who have committed more serious crimes, a practice that may increase deviant attitudes and behaviors among status offenders, such as the development of antisocial perspectives and gang affiliation (Levin and Cohen 2014). Juveniles experiencing confinement are eventually forced to navigate the barriers to reentry in the community, home, and school, which increases the chance of being rearrested and re-incarcerated (Levin and Cohen 2014). Further, research has shown that confinement fails to address underlying causes of status-offending behavior, and thus does not deter youths from committing future crimes (Hughes 2011; Holman and Ziedenberg 2006). Although most youths naturally “age out” of delinquency when social controls are enforced (Sweeten, Piquero, and Steinberg 2013; Tremblay et al. 2004), institutionalization can negate this type of development. When handled as delinquents and placed in juvenile facilities, status offenders may be put into environments that can lead to physical and emotional harm. Institutionalizing juveniles may negatively affect their social development by disrupting their social connectedness and support from family, school, and the community (Hughes 2011). Confinement in a secure environment can increase violent tendencies, exacerbate risk factors, and increase recidivism risk (Holman and Ziedenberg 2006). Studies done on juvenile delinquents show that community-based programming can be more effective than detention in preventing future crime (Hughes 2011; Holman and Ziedenberg 2006; Kendall 2007; Salsich and Trone 2013; Petitclerc et al. 2013). Although status offenders are noncriminal youths, they often possess many risk factors for future offending, which can be exacerbated by formal processing through the juvenile justice system. Research illustrates the need for immediate and efficacious community-based alternatives to help status-offending youths and their families. Strengthening of family relationships, social-control mechanisms, and other protective factors are integral in preventing future criminality among status offenders (Salsich and Trone 2013).

Conclusions – Currently, status-offense laws, terminology, and programs and practices vary widely across states (Hockenberry and Puzzanchera 2014). Some states choose to process juveniles formally through the system, with the idea that harsh treatment of young offenders will deter them from future criminal activity. Conversely, some research has shown that by further entangling young people and children in the juvenile justice system, they become more likely to be involved in a life of crime because of their increased exposure to other criminal peers, the justice system, and the effects of “labeling” (Petrosino et al. 2010). A meta-analysis by Petrosino and colleagues (2010) assessed 27 studies and found a small negative effect for formal system processing of juveniles, meaning that juveniles who were formally processed through the juvenile justice system were more likely to recidivate, compared with youths who were diverted from the system (although the difference was not statistically significant). As a result, more states are exploring alternative strategies to divert status offenders from the juvenile court process altogether (Coalition for Juvenile Justice 2012). Some resources have been developed for jurisdictions looking for specific information about options in the treatment of status-offending youths. For example, through its participation in the MacArthur Foundation’s Models for Change Resource Center Partnership, the Status Offense Reform Center (SORC) provides tools and techniques to improve the juvenile justice system in support of the equitable, rational, and effective treatment of status offenders. The SORC, operated by the Vera Institute of Justice (n.d.), serves as an information base for juvenile justice stakeholders and is available to provide information, guidance, and assistance to policymakers and practitioners who are interested in preventing the confinement of status offenders (Salsich and Trone 2013). Jurisdictions can make use of this information to consider options to the processing and treatment of status offenders and ensure that they are deinstitutionalized.

- : Status Offender is shared under a CC BY 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by LibreTexts.

: Dual Status / Dependency vs Delinquency

It is important to understand the concept of “dual status” in juvenile law and detention. It may be shocking to learn that a majority of juvenile “delinquents” entered the juvenile justice system through dependency. As a result of parental abuse, neglect or incarceration, a child can enter the system at any point in their life as a dependent. This means their parent can no longer care for them. A majority of dependents are placed with another relative, but not all. Those children often end up in foster homes or group homes.

When a juvenile enters the juvenile justice system as a result of parental neglect or abuse it is called dependency. The area of law that governs how we treat juveniles in California falls under the Welfare and Institutions Code section 300:

Note

ARTICLE 6. Dependent Children—Jurisdiction [300 – 304.7]

(Article 6 added by Stats. 1976, Ch. 1068.)

300.

A child who comes within any of the following descriptions is within the jurisdiction of the juvenile court which may adjudge that person to be a dependent child of the court.

When we look at juvenile delinquency, these are juveniles that have committed a crime. In juvenile courts, this is called wardship and is also guided by the Welfare and Institutions Codes but falls under section 602 in California.

Note

ARTICLE 14. Wards—Jurisdiction [601 – 608]

(Heading of Article 14 renumbered from Article 5 by Stats. 1976, Ch. 1068.)

602.

Except as provided in Section 707, any person who is under 18 years of age when he or she violates any law of this state or of the United States or any ordinance of any city or county of this state defining crime other than an ordinance establishing a curfew based solely on age, is within the jurisdiction of the juvenile court, which may adjudge such person to be a ward of the court.

(Amended November 8, 2016, by initiative Proposition 57, Sec. 4.1.)

The concerning part of this distinction is many “juvenile delinquents” who commit crimes began in the juvenile dependency court as a result of abuse or neglect. We refer to these juveniles who fall under both dependency as an abused or neglected child and as a ward after committing a crime as “Dual Status” because they fall under both conditions in the Welfare and Institutions Code.

Note

Pin It! Dual Status For further research:

Family and Juvenile Law Advisory Committee: Dual-Status Youth Data Standards Working Group

Podcast on Dual Status

- : Dual Status / Dependency vs Delinquency is shared under a CC BY 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by LibreTexts.

: Foster Home Placement

Foster care, a part of the state child welfare system designed to protect abused and neglected children, provides a 24-hour state supervised living arrangement for children who need temporary substitute care because of abuse or neglect. The foster care system in California is a state supervised, county administered system. The California Department of Social Services provides oversight to 58 county child welfare agencies that provide direct administration and supervision of children in the foster care system.

Children are most often placed in foster care after they have been removed from their home by a county child welfare agency, and a juvenile court has found their parents cannot care for them. A child who has been declared a “ward” of the court for committing a violation of law may also be placed in foster care if the court finds that returning the child home would be contrary to the child’s welfare.

Overview of the Juvenile Justice System. Every county child welfare agency must maintain a 24-hour response system to receive and investigate reports of suspected child abuse or neglect. Once a call is received, the agency pursuant to the Emergency Response Protocol must determine if the allegations require an in-person investigation and, if so, whether that investigation must be immediate.

Upon completion of the investigation, the agency must determine whether the allegations are substantiated, inconclusive or unfounded. Based on the risk posed to the child, the agency in all three cases may close the case with or without providing the family with referrals to community organizations for services. If the allegations are substantiated or inconclusive, the agency may keep the case open and offer the family voluntary services to remedy and prevent future abuse or neglect without court intervention. Voluntary services include in home emergency services for up to thirty days or family maintenance services for up to 6 months without removing the child, or voluntary foster care placement services for up to 6 months.

If the allegations are substantiated, the agency may seek court intervention and either:

- Keep the child in the home, file a petition in juvenile court to declare the child dependent, and provide the family with court supervised family maintenance services; or

- Remove the child from the home and file a petition in juvenile court (within 48 hours of the child’s removal excluding non- judicial days) to declare the child dependent.

Dependency proceedings may also be initiated by any person through an application to the county child welfare agency. The agency must immediately investigate to determine whether a dependency petition should be filed in juvenile court and notify the applicant within three weeks after the application of its filing decision and the reasons for the decision. If the agency fails to file a petition, the applicant may, within one month after the initial application, seek review of the decision by the juvenile court.

If the child is removed from his or her parents’ home, the social worker will file a petition with the juvenile court requesting that the court become involved in the child’s life because the child is alleged to be abused or neglected.9 The parents must be given notice of the removal, a telephone contact for the child, and the date, time and place of the detention hearing upon filing of the petition in juvenile court.10 The child will be placed in a foster care setting until the court determines whether the child should remain in placement or should be returned to the parent’s home.

- : Foster Home Placement is shared under a CC BY 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by LibreTexts.

: Special care placement

Special Education in Juvenile Delinquency Cases Individual Disability Education Act’s (IDEA) comprehensive system of identification, evaluation, service delivery, and review has special relevance for juvenile justice professionals. The purpose of the special education system, like the juvenile justice system, is to provide individualized services designed to meet the needs of a particular youth. The enhanced behavioral intervention and transition service needs requirements in the 1997 IDEA amendments bring special education goals even closer to those of the juvenile court. Moreover, the careful documentation of service needs and ongoing assessment of progress required by IDEA bring valuable informational resources to juvenile justice professionals. This section presents a brief overview of how special education information may be helpful as cases make their way through juvenile court.

Some of the issues discussed, such as insanity or incompetence, arise only occasionally. Others, such as the impact on disposition of whether a child has a disability, are relevant in every case in which a delinquent youth is eligible for special education services.

Figure 8.6 Law enforcement transport juveniles to detention facilities such as this to be booked. Security is a concern and officers must enter through a sally port. This is a secure area where the first door is locked before the second door can be opened into the facility. Booking photo by Tabitha Raber is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

Intake and Initial Interviews

The short time frame for juvenile court proceedings leaves little room for missed opportunities. Juvenile justice professionals must be alert from the earliest moment for clues to the youth’s special education status or existing unidentified disabilities. This process, which should become part of the standard operating procedure, includes carefully interviewing the youth and his or her parents, routinely gathering educational records, procuring examinations by educational and mental health experts, investigating educational services at potential placement facilities, and coordinating juvenile court proceedings with the youth’s IEP team.

Under the 1997 IDEA amendments, whenever a school reports a crime allegedly committed by a youth with a disability, school officials must provide copies of the youth’s special education and disciplinary records to the appropriate authorities to whom the school reports the crime, but only to the extent that the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) permits the transmission. FERPA allows school officials to transmit school records to law enforcement officials only if parents’ consent in writing to the transmission and in certain other narrowly tailored situations (see 34 C.F.R. § 99.30). This requirement should help ensure that, at least in appropriate school-related cases, special education history, assessments, and service information are readily available early in the court process.

Juvenile justice professionals can learn to recognize disabilities by carefully reading the legal definitions of disability. It is important to understand that youth may have a variety of impairments that are not immediately apparent. Numerous checklists and screening instruments are available to help recognize signs of disabilities and to determine eligibility for special education services (National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges, 1991).

If circumstances suggest the need for an eligibility evaluation, modification of a previously existing IEP, or some other exercise of the youth’s rights under special education law, juvenile justice professionals should ensure that appropriate action is expeditiously taken. They should request that parents give written consent for the release of records and should submit a written request for information, evaluation, or review to the LEA.

Juvenile justice professionals could start by contacting the LEA to obtain its policies and procedures for providing special education services to youth in the juvenile justice system. Some districts have designated an individual to deal with compliance issues, and that person may be helpful in expediting or forwarding requests to the right person or agency. Most jurisdictions have a number of other groups that can provide advocacy or other assistance in navigating the special education system. Protection and advocacy offices, special education advocacy groups, learning disabilities associations, and other groups providing support or advocacy for particular disabilities may greatly assist juvenile justice professionals.

Determination of Whether Formal Juvenile Proceedings Should Go Forward

Nothing in IDEA prohibits an agency from “reporting a crime committed by a child with a disability to appropriate authorities” or prevents law enforcement and judicial authorities from “exercising their responsibilities with regard to the application of Federal and State law to crimes committed by a child with a disability. These provisions, outlined in the 1997 amendments, were made in response to concerns that IDEA’s procedural protections could be interpreted to preclude juvenile court jurisdiction over school- related crimes committed by youth with disabilities. In the past, at least one court ruled under State law that a school could not initiate a juvenile court prosecution as a means of evading the procedural requirements of IDEA. Other courts found the juvenile court lacked jurisdiction in cases involving noncriminal school related misconduct in which special education procedures had not been followed.

In at least one case decided after the 1997 amendments, the court confirmed that IDEA does not prevent juvenile courts from exercising jurisdiction over students with disabilities, even if the school is attempting to evade its special education responsibilities. Nonetheless, intake officers and prosecutors should scrutinize whether such evasion has occurred in determining whether a particular case belongs in the juvenile justice system and how it should be processed. Courts and hearing officers have stressed that the school’s responsibility to comply with IDEA procedural requirements does not end when a youth with a disability enters the juvenile justice system.

Even if courts have the power to act, that does not mean the power should be exercised in every case. Long before the 1997 IDEA amendments, a number of courts found that the best course was to dismiss the juvenile court case or defer it until special education proceedings stemming from the misbehavior could be completed.

Many juvenile justice professionals have encountered cases in which a youth enters the juvenile justice system for a relatively minor offense and his or her stay escalates into long-term incarceration because of the youth’s inability to succeed in programs developed for low-risk delinquent youth. This may happen either because the disability-related behavior makes it difficult for the youth to understand or comply with program demands or because his or her behavior is misinterpreted as showing a poor attitude, lack of remorse, or disrespect for authority.

If the juvenile court petition involves a youth with an identified or suspected disability, juvenile justice professionals should first consider whether school-based special education proceedings could provide services or other interventions that would obviate the need for juvenile court proceedings. This is particularly true for incidents occurring at school. The 1997 IDEA amendments require thorough scrutiny of behavioral needs and implementation of appropriate interventions that may far exceed what most juvenile courts are able to provide. In appropriate cases, the juvenile court may wish to consider:

Continuing or deferring the formal prosecution pending the outcome of special education due process and disciplinary proceedings that may alleviate the need for juvenile court intervention.

Continuing or deferring the formal prosecution pending the outcome of special education due process and disciplinary proceedings that may alleviate the need for juvenile court intervention.

Placing first-time offenders and/or youth alleged to have committed offenses that are not considered too serious for informal handling into diversion or informal supervision programs. Through such programs, the court imposes specific conditions on the youth’s behavior, such as regular school attendance, participation in counseling, observation of specified curfews, or involvement in community service programs. If the youth successfully complies with these conditions, the case is dismissed at the end of a specified period—usually 6 months to 1 year. Allowing the youth to remain in the community, subject to such conditions, may facilitate the completion of special education proceedings while ensuring heightened supervision of the youth. Through IEP development or modification, the youth might be determined eligible for services that supplant the need for formal juvenile court proceedings.

Placing first-time offenders and/or youth alleged to have committed offenses that are not considered too serious for informal handling into diversion or informal supervision programs. Through such programs, the court imposes specific conditions on the youth’s behavior, such as regular school attendance, participation in counseling, observation of specified curfews, or involvement in community service programs. If the youth successfully complies with these conditions, the case is dismissed at the end of a specified period—usually 6 months to 1 year. Allowing the youth to remain in the community, subject to such conditions, may facilitate the completion of special education proceedings while ensuring heightened supervision of the youth. Through IEP development or modification, the youth might be determined eligible for services that supplant the need for formal juvenile court proceedings.

Dismissing the case in the interest of justice. This option should be considered in cases in which the disability is so severe that it may be difficult or impossible for the youth to comply with court orders. This may occur, for example, if the offense is relatively minor; the youth suffers from mental illness, emotional disturbance, or mental retardation; and/ or services are forthcoming through the special education system.

Dismissing the case in the interest of justice. This option should be considered in cases in which the disability is so severe that it may be difficult or impossible for the youth to comply with court orders. This may occur, for example, if the offense is relatively minor; the youth suffers from mental illness, emotional disturbance, or mental retardation; and/ or services are forthcoming through the special education system.

Note

Think about it . . . Mental health treatment

Many young people in South Carolina have better access to mental health care in juvenile jail than they do outside the fence, back in their own communities. Read these personal interviews of youth in the system in treatment centers. Do you think this approach to treating juvenile delinquents with mental illness instead of jailing them is effective? Why or why not?

Detention

Youth taken into secure custody at the time of arrest are entitled to judicial review of the detention decision within a statutory time period. Depending on the jurisdiction and characteristics of the case, the length of detention may range from several hours to several months. Many professionals view the detention decision as the most significant point in a case. Detention subjects the youth to potential physical and emotional harm. It also restricts the youth’s ability to assist in his or her defense and to demonstrate an ability to act appropriately in the community.

Unfortunately, youth with disabilities are detained disproportionately (Leone et al., 1995). Experts posit that one reason for this is that many youths with disabilities lack the communication and social skills to make a good presentation to arresting officers or intake probation officers. Behavior interpreted as hostile, impulsive, unconcerned, or otherwise inappropriate may reflect the youth’s disability. This is another reason why it is important to establish the existence of special education needs or suspected disabilities early in the proceedings. Juvenile justice professionals must be sensitive to the impact of disabilities on case presentation at this initial stage and work to dispel inaccurate first impressions at the detention hearing.

In some cases, it may be appropriate for the court to order the youth’s release to avoid disrupting special education services. This is particularly true if adjustments in supervision (e.g., modification of the IEP or behavioral intervention plans) may reduce the likelihood of further misbehavior pending the jurisdictional hearing. Similarly, if there are early indications that a special education evaluation is needed, it may be important for the youth to remain in the community to facilitate the evaluation. Many jurisdictions have home detention programs that facilitate this type of release by imposing curfews or other restrictions on liberty that allow the youth to live at home and attend school pending the outcome of the delinquency proceedings.

Education

Education may be the single most important service the juvenile justice system can offer young offenders in its efforts to rehabilitate them and equip them for success. School success alone may not stop delinquency, but without it, troubled youth have a much harder time (Beyer, Opalack, and Puritz, 1988). When special education needs are evident, they should be an essential part of the social study report prepared by the probation department to guide the court in making its disposition order. Moreover, juvenile justice professionals should coordinate disposition planning with education professionals to avoid conflict and to take advantage of the rich evaluation resources and services available through IDEA.

The resulting disposition order should reflect the court’s review of special education evaluations and the goals, objectives, and services to be provided under the IEP. If the youth is to be placed out of the home, the court should demand specific assurance that the facility will meet the youth’s educational needs under IDEA. The juvenile court should also use its disposition powers to ensure special education evaluation and placement for previously unidentified youth who show indications of having a disability.

In deciding whether or where to place a youth with a disability, it is also important for the court to understand the impact of the disability on behavior. Youth with attention deficit disorder (ADD), for example, commonly act impulsively, fail to anticipate consequences, engage in dangerous activities, have difficulty with delayed gratification, have a low frustration threshold, and have difficulty listening to or following instructions. They may begin to associate with delinquents or self-medicate through drugs and alcohol because they are rejected by others. Proper medication has a dramatic effect in helping many of these youth control their behavior, and a variety of professionals are skilled in treating ADD in medical, psychiatric, or educational settings (Logan, 1992). Unless the characteristics of ADD and the existence of effective interventions are recognized, youth with this disability stand a good chance of being treated harshly, often through incarceration, based on the outward manifestations of their disability. Juvenile justice professionals should respond appropriately to evidence of such disabilities by ensuring that appropriate medical, mental health, and other services are provided.

Juvenile justice professionals also must learn to recognize potential problems for youth with certain disabilities in particular settings, so as not to set the youth up for failure. This does not mean that juvenile justice professionals need to become diagnosticians or clinicians. However, they should consult with education, mental health, and medical professionals. It is important

to seek professional advice about the kinds of settings in which the youth can function best and the kinds of settings most likely to lead to negative behavior. For example, a youth with an emotional disturbance may not be able to function in the large dormitory setting typical of some institutions. Such youth may feel especially vulnerable because of past physical or sexual abuse or may simply suffer from over stimulation in an open setting. They may require a setting in which external stimuli are reduced to the greatest extent possible and intensive one-on-one supervision is provided. Youth with other disabilities may need programs that minimize isolation and emphasize participation in group activities.

8.8: Special care placement is shared under a CC BY 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by LibreTexts.