Chapter 1 – Concepts of Corrections as a Subsystem of the Criminal Justice System

Joel George

Learning Objectives

- Discuss the history and development of corrections and the prison system

- Describe the goals of the correctional system

- Explain the different types of deterrence

- Assess Mandatory Minimums and Tree-Strike Laws

- Examine Recidivism and Sentences: Evidence-based Practices

Introduction

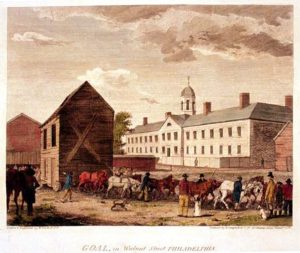

This chapter delves into corrections, the third pillar of the criminal justice system. It examines the nature of corrections and its significance within this framework. Historically, prior to the establishment of a formal structure, religious influences significantly shaped the American criminal justice system. The roots of American corrections can be traced to the colonial era, where early settlers embraced elements of the British punishment system. During the Enlightenment period, reforms led to a notable decline in corporal punishment as the concept of penitentiaries took hold. The first U.S. penitentiary, the Walnut Street Jail in Philadelphia, founded in 1773, was designed to reflect the European penitentiary model. Shortly after, the New York system emerged, marked by the opening of the Auburn penitentiary in 1819. In Louisiana, the correctional landscape, particularly the Angola prison—previously a slave plantation—has gained recognition as one of the most secure prisons in the country. As the prison system progressed, its goals expanded to incorporate deterrence, incapacitation, rehabilitation, and retribution. Nonetheless, a significant divergence occurred, with prisons in the South and West evolving differently from those in the Northeast, especially concerning lease systems that permitted businesses to exploit prison labor. The practice of convict leasing gained traction in the U.S. following the Civil War during the post-slavery era. In the 1980s, the nation faced a drastic rise in crime rates, resulting in overcrowded prisons, a situation exacerbated by mandatory minimum sentencing and three-strike laws. This chapter also highlights that recidivism plays a significant role in prison overcrowding and traces the development of the reformatory movement from the inception of corrections to modern reform initiatives in Louisiana.

1.1 History and Philosophy

The history of American corrections dates to the colonial era. Early settlers adopted the British approach to punishment, focusing on deterring crime through public humiliation and corporal punishment, like whipping and branding. These harsh measures aimed to shame offenders and uphold social order. Public execution was reserved for serious crimes such as murder, rape, perjury, witchcraft, and piracy.

Early Beliefs and Punishments

The religious beliefs of the milieu significantly shaped the early American justice system. Crime was viewed not only as harm against a victim or wrongdoing against society, but also as a sin against God. For instance, the colony’s laws in Puritan New England reflected biblical commandments, and the justice system focused not just on punishing the offender to deter future crimes, but also on purging the offender of the sin against God. This influence of faith on the legal system is a key aspect of the history of American corrections.

History of Jails

Jails in colonial America generally served only to hold individuals awaiting trial or punishment rather than as places for long-term incarceration (Rotman, 1990).

Before the 1800s, common law countries, including the United States, heavily relied on physical punishments to deal with wrongdoers. However, a significant shift occurred during the Age of Enlightenment. Reformers began to steer the criminal justice system away from corporal punishment and toward incarceration and offender reform. This marked a departure from the long-standing practice of inflicting pain as punishment. One of the key figures in this reform was John Howard, who advocated for the use of penitentiaries. These institutions, as their name suggests, were designed to encourage offenders to be penitent, engaging in work and reflecting on their misdeeds. To create the right environment for penitence, prisoners were often kept in solitary cells, providing ample time for reflection.

Jails and prisons are crucial components of the criminal justice system, each serving a distinct purpose. The idea of jails has a long history, with the historical roots of American jails tracing back to the ‘jails’ of feudal England. Sheriffs operated these early jails, and their primary purpose was to hold accused individuals awaiting trial. The functions of the jail under the English model remain the same. The jail’s function was extended to house those convicted of minor offenses and sentenced to short terms of incarceration. They were also used for other purposes, such as holding the mentally ill and vagrants, a term used to describe homeless or jobless individuals. The advent of a separate juvenile justice system and its development alleviated the burden of caring for these later categories.

Jails primarily serve individuals who have been arrested or are awaiting trial, whereas prisons hold those who have been convicted of crimes and are serving their sentences. This distinction is crucial for the administration of justice; it also enlightens us and raises our awareness of the lives of incarcerated individuals. The need for social control began to increase, and in the 1800s, jails started to evolve in response to the penitentiary movement.

History of Prisons

In Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the Walnut Street Jail, established in 1773, was one of the first attempts to model European penitentiaries. The system used there later became known as the Pennsylvania System. Under this system, inmates were kept in solitary confinement in small, dark cells. A key element of the Pennsylvania System was that no communications whatsoever were allowed. The New York system evolved similarly, starting with the opening of New York’s Auburn Penitentiary in 1819. This facility employed what came to be known as the congregate system. Under this system, inmates spent their nights in individual cells but were required to assemble in workshops during the day. Work was serious business, and inmates were prohibited from talking on the job or at meals. This emphasis on labor has been associated with the values accompanying the Industrial Revolution. However, by the middle of the nineteenth century, the future of the penitentiary movement was clouded with uncertainty. No evidence had been mustered to suggest that penitentiaries had any real impact on Rehabilitation and Recidivism, casting doubt on the effectiveness of the system.

However, early on, vocal critics of this system began to speak out against the practice of solitary confinement, believing it was emotionally damaging to inmates. This early criticism highlighted the evolving nature of justice systems and the ongoing debate about the best approach to rehabilitation.

After the belief that “nothing works” became popular, the crime control model emerged as the dominant paradigm of corrections in the United States. This model criticized the rehabilitative approach as being “soft on crime.” “Get tough” policies became the norm throughout the 1980s and 1990s, leading to lengthy prison sentences becoming common. As a result, there has been a dramatic increase in prison populations and a corresponding rise in corrections expenditures. These expenditures have reached a level where many states can no longer sustain their correction departments. The pendulum is swinging back toward a rehabilitative model that emphasizes community corrections. While the community model has existed alongside the crime control model for many years, it is gaining prominence.

When it comes to the philosophy of criminal sanctions, what people believe to be appropriate is primarily determined by the theory of punishment to which they adhere. Individuals tend to align with the punishment theory that is most likely to yield the outcome they consider correct. This belief system regarding the purposes of punishment often extends into the political realm. Politics and correctional policy are closely intertwined. Many changes in correctional policy in the United States during this time mirrored the prevailing political climate.

During the more liberal periods of the 1960s and 1970s, criminal sentences were largely the responsibility of the government’s judicial and executive branches. The role of the legislatures during this era was to develop sentencing laws with rehabilitation as the main objective. However, in the politically conservative climate of the 1980s and 1990s, lawmakers removed much of that power from the judicial and executive branches. Much of the political rhetoric during this period focused on “getting tough on crime.” The correctional goals of retribution, incapacitation, and deterrence became predominant, while rehabilitation was relegated to a secondary role.

Historical overview of the Louisiana correctional system

Louisiana’s correctional system has historical significance due to Angola Prison, officially known as Louisiana State Penitentiary, which is located on land that was once a slave plantation in Louisiana. Angola is recognized as one of the highest-security prisons in the country, and its history is closely linked to the leasing system that was prevalent in Louisiana for many centuries.

After the Civil War ended and slavery was abolished in the South, there was a rise in forms of labor such as convict leasing.

Louisiana especially embraced the practice of profiting from renting out inmates. Primarily, African Americans who had been unjustly convicted of trivial or falsely accused crimes were affected. Angola became infamous for its working conditions, where prisoners were loaned out to plantation owners, railways, and various enterprises. These brutal leasing situations in Louisiana are frequently likened to the hardships faced by slaves prior to their liberation, solidifying Angola’s notoriety as a site of misery and exploitation.

By the 20th century, attempts to revamp Louisiana’s facilities led to some improvements. Despite this progress, Angola’s severe notoriety continued. The penitentiary became a topic in conversations about imprisonment, racial disparities, and prison restructuring, particularly as the state gained recognition as the “Prison Capital of the World” because of its substantial incarceration rates.

1.2 Goals of the Correctional System

- Deterrence

- Incapacitation

- Rehabilitation

- Retribution

When it comes to the philosophy of criminal sanctions, what people believe to be appropriate is primarily determined by the theory of punishment to which they subscribe. That is, individuals tend to agree with the theory of punishment that is most likely to produce the outcome they consider correct. This system of beliefs regarding the purposes of punishment often spills over into the political arena. Politics and correctional policy are intricately related. Many of the changes observed in corrections policy in the United States during this time reflected the political climate of the day. During the more liberal periods of the 1960s and 1970s, criminal sentences were largely the purview of the judicial and executive branches of government. The role of the legislatures during this period was to design sentencing laws with rehabilitation as the primary goal. In the politically conservative era of the 1980s and 1990s, lawmakers stripped much of that power from the judicial and executive branches. The political rhetoric of this time largely centered on “getting tough on crime.” The correctional goals of retribution, incapacitation, and deterrence became predominant, while rehabilitation was shifted to a more distant position.

Deterrence

Throughout the ages, a popular notion has persisted: the fear of punishment can reduce or eliminate undesirable behavior. This idea has consistently attracted attention from criminal justice thinkers and has been formalized in various ways. The Utilitarian philosopher Jeremy

Bentham is credited with articulating the three elements necessary for effective Deterrence: punishment must be administered with celerity, certainty, and appropriate severity. These elements relate to a type of rational choice theory, which posits that individuals consider the consequences before committing a crime. If the rewards of the crime outweigh the potential punishment, they are likely to engage in the prohibited act. Conversely, if the punishment is perceived as outweighing the rewards, they will refrain from committing the crime. Criminologists sometimes borrow the term “cost-benefit analysis” from economists to explain this decision-making process. When assessing the effectiveness of deterrence, it is crucial to distinguish between general and specific deterrence. General Deterrence suggests that each individual punished by the law serves as a warning to others contemplating the same unlawful act.

Specific Deterrence is the idea that the individuals punished by the law will not commit their crimes again because they “learned a lesson.” It uses punishment as a deterrent to discourage a specific individual from re-offending

Critics of deterrence theory point to high recidivism rates as proof that the theory does not work. Recidivism means a relapse into crime. In other words, those who are punished by the criminal justice system tend to reoffend at a very high rate. Some critics also argue that rational choice

The theory does not work. They argue that crimes of passion and crimes committed by those under the influence of drugs and alcohol are not the result of a rational cost-benefit analysis. As unpopular as rational choice theories may be with certain schools of modern academic criminology, they are critically important for understanding how the criminal justice system functions. This is because nearly the entire criminal justice system is based on rational choice theory. The idea that people commit crimes because they decide to do so is the very foundation of criminal law in the United States. In fact, the intent element must be proven beyond a reasonable doubt in almost every felony acknowledged by American criminal law before a conviction can be secured. Without a culpable mental state, there is no crime (with very few exceptions).

Incapacitation

Incapacitation is a pragmatic goal of criminal justice. The idea is that if criminals are confined in a secure environment, they cannot go around victimizing everyday citizens. The limitation of incapacitation is that it is effective only while the offender is incarcerated. There is no doubt that incapacitation reduces crime to some extent. The primary issue with incapacitation is the cost. There are significant social and moral costs when the criminal justice system removes individuals from their homes, separates them from their families, and takes them out of the workforce for an extended period. Additionally, this model incurs substantial financial costs. Lengthy prison sentences lead to large prison populations, which necessitate a vast prison industrial complex. These expenses have created a crippling financial burden on many states.

Rehabilitation

Overall, rehabilitation efforts have yielded poor results when measured by recidivism rates. Those whom the criminal justice system attempted to help tend to reoffend at about the same rate as those who serve prison time without any treatment. Advocates of rehabilitation highlight that past efforts failed due to underfunding, poor planning, or inadequate execution. Today, there is a significant trend among prisons to revert to the rehabilitative model. However, this new initiative has been guided by “evidence-based” treatment models, which require treatment providers to demonstrate that their programs lead to significant improvements in recidivism rates. This movement begins during incarceration with programs tailored to address the specific needs of offenders. As the offender approaches their release date, the focus shifts to reintegrating them into society. Efforts include modifying behavior so that offenders become law-abiding citizens. Prison case managers collaborate with offenders to locate available community resources, strengthen family relationships, and develop employment opportunities for them to become productive members of society. Upon release, offenders often receive support from their probation or parole officers, who provide supervision, treatment resources, and employment information.

Retribution

Retribution refers to assigning offenders a punishment that corresponds to the harm caused by their crimes. Proponents of this concept assert that penalties should align with the severity of the offenses, a principle known as the doctrine of proportionality. This doctrine was championed by the early Italian criminologist Cesare Beccaria, who criticized the extreme punishments of his era as excessively harsh for many crimes. The phrase “just desert” is commonly used to denote a punishment that is fitting in relation to the offense. However, in practice, achieving proportionality proves to be challenging. Legislatures struggle to objectively assess criminal culpability, resulting in a process that relies on legislative agreement and tends to be uncertain at best.

1.3 The Convict Leasing System

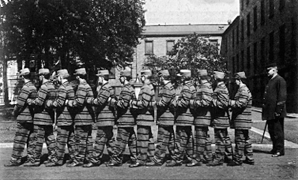

Prisons in the South and West were quite different from those in the Northeast. In the Deep South, the lease system developed. Under this system, businesses negotiated with the state to exchange convict labor for the care of inmates. Prisoners were primarily used for hard manual labor, such as logging, cotton picking, and railroad construction. Eastern ideas of penology did not catch on in the West, except in California. Before statehood, many frontier prisoners were held in federal military prisons.

The convict leasing system is a form of prison labor used in the United States after the Civil War. It represented one of the most controversial and darkest chapters in the history of American corrections. The convict leasing system originated in the southern states during the Reconstruction era. Following the end of the Civil War, the economy of the southern states had virtually collapsed. The slave labor upon which the economy depended was no more due to the abolition of slavery in 1865 with the ratification of the 13th Amendment. With the loss of their primary labor force, the Southern states, seeking new ways to sustain agricultural and industrial productivity, introduced the convict leasing system. The idea was to fill the vacuum created by the loss of enslaved labor by using prison inmates who were disproportionately African American due to the criminalization of Black life through Black Codes and vagrancy laws (Alexander, 2012). These laws were deliberately designed to reestablish control over African Americans through criminalization of their everyday behavior to ensure a steady supply of convict labor for private businesses, such as plantations, railroads, and mining companies, in exchange for payment to the state. The Southern states tried to justify the convict leasing system by arguing that it was meant to teach inmates important skills, reduce idleness, and help cover the costs of incarceration (Adamson, 1983).

Development of the Convict Leasing System

Alabama is generally regarded as the state that initiated the Convict Leasing System, which became law in 1846 and lasted until it was completely abolished by President Franklin Roosevelt on December 12, 1941. Louisiana adopted the policy of convict leasing around the same time as Alabama, and some sources claim that it began in Louisiana as early as 1844. Georgia implemented the practice in 1868. Convict leasing was a system of involuntary labor that exploited inmates, compelling them to provide free labor while disproportionately targeting African Americans. Under this system, prisoners were leased to private companies or individuals for hard labor, often in dehumanizing conditions (Lichtenstein, 1996). Following the Civil War in 1865, the convict leasing system spread across the Southern states. Freed African Americans were deliberately targeted and arrested for minor or fabricated offenses. The Southern states were driven by the need for a steady supply of cheap and expendable labor for economic activities (Blackmon, 2008). The convict leasing system persisted into the early 20th century and has been widely criticized as a continuation of slavery by another name. The prisoners were predominantly African Americans, forced to work under terrible conditions characterized by extreme brutality, inadequate food, unsanitary environments, and frequent physical abuse. Deaths among the leased convicts were significantly high, as these individuals were often viewed as expendable labor.

1.4 Racial Dimensions and Exploitation

To circumvent the 13th Amendment, which abolished slavery, the Southern states capitalized on a clause in the amendment that permitted involuntary servitude as punishment for committing a crime. The Southern states exploited this clause to justify the mass incarceration of African Americans and their subsequent leasing to private industries. The convict leasing system became a means by which the Southern states maintained white supremacy and economic control over newly freed blacks (Oshinsky, 1996).

Louisiana and Inequalities

Modern Reforms in Angola and Historical Legacy

Angola, particularly its prison system, has undergone some reforms in recent years, although progress has been slow and fraught with challenges. The prison’s deep-rooted history of racial inequality and its origins as a slave plantation continue to affect its current policies and operations. While modernization efforts have introduced educational programs, work-release initiatives, and faith-based rehabilitation services, the prison’s past looms large. Recent attempts have been made to address issues such as overcrowding and harsh sentencing policies, particularly impacting non-violent offenders (Walsh, 2016). These reforms have included reducing incarceration rates for drug-related offenses and increasing parole options for certain inmates. Nevertheless, Angola remains notorious for its high number of inmates serving life sentences without parole, a testament to Louisiana’s historically rigorous sentencing laws.

End of Convict Leasing and Its Legacy

In the early 20th century, the convict leasing system faced increasing criticism from opponents who were alarmed by its cruelty and exploitation. Frequent reports of abuse and public outcry ultimately led to the gradual abolition of the system. In 1928, Alabama became the last state to formally end convict leasing (Lichtenstein, 1996). The lasting impact of convict leasing on the American criminal justice system continues to this day. The prison labor programs that endure today, including chain gangs and modern-day prison industries, can be traced back to the convict leasing system. Similarly, the racial disparities in incarceration rates within the contemporary U.S. penal system, which disproportionately affects African Americans, can be linked to the convict leasing era.

Louisiana Corrections and Convict Leasing

Angola still houses over 5,000 inmates, most of whom are serving life sentences. The prison’s grim past is evident in aspects such as the fields where inmates labor and the controversial prison rodeos, which raise ethical concerns about the treatment of incarcerated individuals. Louisiana’s correctional systems bear the lingering impact of practices like convict leasing, reflecting challenges such as inequality, overcrowding, and the human toll of imprisonment.

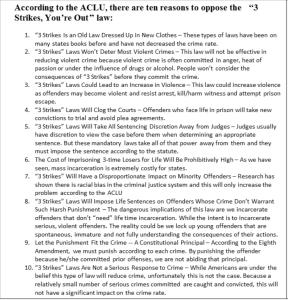

1.5 Prison Overcrowding

During the 1980s, crime rates in America experienced a significant spike. This increase was attributed to various factors, with most experts identifying drug trafficking and gang violence as key contributors. Drug dealers and gangs resorted to violent measures to protect their territories from rivals. The media extensively reported on the crisis’s impact on local neighborhoods, prompting society to demand solutions. In response, legislation was enacted that established tougher sentencing laws, including ‘Three-Strikes Law,’ which imposed life sentences on individuals with three felony convictions. This change fundamentally transformed prison management, leading to longer sentences and considerable overcrowding in facilities. Furthermore, many individuals released from prison returned to custody due to parole infractions—a process known as recidivism. The California Department of Correction and Rehabilitation noted that in the early 2000s, the recidivism rate was around 65%, peaking at 67.5% between 2005 and 2006. By the 2000s, the inmate population had reached alarming levels.

California’s prison overcrowding has reached critical levels, prompting inmates to file lawsuits claiming violations of their Eighth Amendment rights. In response, the U.S. Supreme Court mandated that the state take urgent measures to reduce its inmate population. Currently, California’s prisons are designed to accommodate roughly 85,000 inmates. However, when the Supreme Court ruled in Brown v. Plata in 2011, the prison system was nearly double its capacity, housing around 156,000 inmates. The Supreme Court determined that this overcrowding violated inmates’ Eighth Amendment rights and upheld a directive from a three-judge panel to reduce the inmate count by approximately 46,000.

Review the Bureau of Prisons website and compare the national figures with the prison population figures for California and Louisiana.

Pin It! Brown v. Plata Case Study

Follow the link to understand the impact Brown v. Plata had on Prison overcrowding.

This problem isn’t limited to California; across the United States, our prison population is among the highest in the world. A report from the American Psychological Association states, “One out of every 100 American adults is incarcerated, a per capita rate five to 10 times higher than that in Western Europe or other democracies, the report found.” While there is no easy fix, it is evident that we must evaluate the current system and explore innovative strategies to address crime and rehabilitate offenders.

1.6 Mandatory Minimum Sentences: Make about Historical

In the mid-1980s, lawmakers established Mandatory Minimum Sentences for a range of drug offenses. The Anti-Drug Act of 1986 led to a significant increase in required sentences for certain drug charges, with penalties based on the type and quantity of drugs involved. Many of these sentences began at 10 years and could extend to life imprisonment. This legislation diminished judges’ discretion and authority, granting district attorneys considerable power; offenders faced substantial prison time based on the charges filed against them. To avoid lengthy trials, many chose to plead guilty to lesser charges.

These federal mandatory minimums were quickly adopted at the state level; however, they often affected low-level drug offenders instead of targeting the “high-level” suppliers or importers that Congress aimed to address. As a result, lengthy sentences were frequently imposed on drug couriers, street-level dealers, or even friends and family of offenders.

However, reforms are underway. Recognizing that these laws have failed to achieve their intended effects, judges and citizens are advocating for their repeal to restore sentencing authority to judges. Several states have recently repealed these laws, but many more must take similar action.

Three-Strikes Laws

Three-Strikes legislation, commonly known as habitual offender laws, imposes stricter penalties for specific crimes, usually violent offenses, for individuals with multiple convictions. In California, for instance, after a first offense, the second and third crimes may result in sentences that are doubled, potentially leading to life imprisonment.

The Three Strikes law mandates that a defendant convicted of a new felony, if they have one prior conviction for a serious felony as outlined in section 1192.7(c), a violent felony per section 667.5(c), or a qualifying juvenile adjudication or out-of-state conviction (a “strike”), must receive a state prison sentence that is double the standard term for that crime. Furthermore, if the defendant has two or more prior strikes, they face a mandatory state prison sentence of at least 25 years to life.

This law aims to incapacitate offenders through lengthy sentences and discourage others from committing crimes due to the repercussions they will face. However, this mandatory sentencing removes judges’ ability to impose appropriate sentences based on the crime, the offender, the victim, and the circumstances involved. Similar to mandatory minimum drug sentencing, this law has significantly contributed to the rise of the American prison population. While the law’s intention was to diminish serious, repeat offenders and permanently incapacitate those who do not “learn their lesson,” critics contend that it has been misapplied, leading to unnecessary incarceration.

1.7 Recidivism

One major factor contributing to prison overcrowding is recidivism, which involves offenders returning to custody for either violating probation or parole conditions or committing new crimes. Often, these returns result from what are termed technical violations of community supervision rather than new criminal behavior. Technical violations arise when offenders disobey a court order or directives from their probation or parole officer. Generally, officials attempt to work informally with offenders before resorting to re-incarceration. However, if an offender consistently disregards instructions or commits a serious breach—such as a domestic violence offender stalking their victim—they may face the prospect of returning to prison. Once community supervision is revoked, a judge holds a hearing. Depending on the severity of the violation, the offender may be sent back to custody for a short time or for the remainder of their original sentence; this hearing is typically referred to as a revocation hearing.

In California, recent reforms aim to reduce recidivism and alleviate prison overcrowding. Launched in 2011, AB 109 Public Safety Realignment sought to address these challenges by shifting significant criminal supervision responsibilities from state prisons and parole officers to local probation departments. For certain “non-violent” offenses, individuals who would have previously faced incarceration are now kept under local custody and supervised by county probation. The state allocated funds to county law enforcement to support evidence-based initiatives focused on reducing recidivism. (Evidence-Based Practices will be discussed in the next section.) This realignment significantly impacted local law enforcement, particularly jails and probation departments, which suddenly had to manage a larger number of offenders. Jails had to adjust to accommodating more individuals than their original capacity and contend with prolonged incarceration periods. Traditionally, California jails housed individuals sentenced to one year or less, but following AB 109, sentences could extend to several years. However, jails are not designed for long-term incarceration of offenders, posing substantial challenges. Furthermore, they lack rehabilitative programs suited for longer-term inmates. To tackle this issue, the state has allocated funding to jails to develop evidence-based treatment programs.

1.8 The Reformatory Movement

Disillusionment with the penitentiary system, combined with overcrowding and understaffing, led to deplorable prison conditions across the country by the middle of the nineteenth century. The American prison experiment, once heralded by European Enlightenment thinkers as one of the greatest achievements of the New Republic, had succumbed to the scourge of time. Additionally, a new concern for the imprisoned arose following the Civil War, stemming from the treatment of enemy combatants in prisoner-of-war camps like Andersonville. The aspirations of the Penitentiary movement had fallen by the wayside due to a broken routine, overcrowding, idleness, corruption, and desperation. New York’s Sing Sing Prison exemplified the brutality and corruption of that era.

With a mandate to conduct a nationwide survey on the state of prisons, the New York Prison Association led the charge into a new era. The Report on Prisons and Reformatories in the United States and Canada, authored by Enoch Wines in 1867, detailed their failure to achieve reformation among those incarcerated. A new wave of reform gained momentum in 1870 after a meeting of the National Prison Association (which would later become the American Correctional Association). At this meeting held in Cincinnati, members issued a Declaration of Principles. This document expressed the belief that prisons should be operated according to a philosophy of reform, and that reform should be rewarded with release from confinement. This ushered in what has been called the Reformatory Movement.

One of the earliest prisons to adopt this philosophy was the Elmira Reformatory, which opened in 1876 under the leadership of Zebulon Brockway. Brockway ran the reformatory with the belief that education was the key to inmate reform. Clear rules were articulated, and inmates who adhered to those rules were classified at higher levels of privilege. Under this “mark” system, prisoners earned marks (credits) toward release. The number of marks required for release was established based on the seriousness of the offense. This marked a shift from the doctrine of proportionality toward indeterminate sentences and community corrections.

The new model of incarceration focused on the reformation of individuals in a secular sense, emphasizing the acquisition of skills needed by young men in the post-war industrial era. Young men received educational and vocational training suited to the “modern” manufacturing of goods in factories. Zebulon Brockway, the director of the first “true” reformatory in Elmira, New York, specified principles and practices designed to “habituation” young men to a lifestyle beneficial to both themselves and society at large. Inmates wore uniforms and participated in military drills and tactics. They learned to read and write, were trained in various trades, exercised, consumed a proper diet, engaged in recreation, and followed a daily regimen that would prove useful upon their release as productive citizens.

Rather than focusing on the “soul” of the offender, the regimen of the reformatory adhered to a “Darwinian” view of adaptation, asserting that physical routine impacted mental processes. A system of rewards and coercion was implemented, with an “indeterminate” sentencing scheme at its core; positive behavior was rewarded with a “graduated approximation to freedom.” These ideas had been tested by Alexander Maconochie, who introduced a “Mark system” to gain compliance on Norfolk Island, a facility for repeat offenders who had previously been transported from England to present-day Australia. The model, later adopted by Sir Walter Crofton, became known as the “Irish Model,” where offenders progressed through varying stages—moving from solitary confinement to public works, followed by an “intermediate prison” akin to a halfway house, and finally to a “Ticket of Leave” system resembling modern-day parole. These concepts, which will be discussed more fully in a later chapter, form the foundation for much of the current system of correctional practices in the United States and beyond.

Louisiana Prison Reform

One significant reform was the 2017 criminal justice overhaul, which aimed to reduce the state’s high incarceration rate (the highest in the world) at that time. This reform package led to a reduction in the prison population by reclassifying non-violent offenses, granting parole to inmates convicted of certain crimes, and introducing alternative sentencing programs, such as drug courts. Despite these reforms, Angola continues to face criticism over conditions such as solitary confinement, inadequate healthcare, and the treatment of elderly inmates, many of whom are serving life sentences for crimes committed decades ago. The prison’s labor programs, including the controversial Angola prison rodeo, also remain a focal point of debate. Many argue that the conditions for inmate labor mirror the exploitative practices of the convict leasing system. The historical legacy of convict leasing and slavery, as embodied by Angola’s past, continues to shape public discourse and policy debates in Louisiana. Activists and reform advocates push for further changes, particularly in the areas of sentencing reform, restorative justice, and improving conditions for inmates, while critics argue that the state’s criminal justice system remains deeply rooted in punitive practices rather than rehabilitation. This ongoing tension between Angola’s past and the push for modern reforms highlights the complex relationship between history and contemporary prison policies in Louisiana. As such, Angola continues to serve as both a symbol of the deeply ingrained issues with the American prison system and a site for potential change and progress.

1.9 Rehabilitation Programs

Rehabilitation programs have long been a part of the criminal justice system. For decades, we have offered various programs, including those for substance abuse, drug diversion, domestic violence, and DUI offenses, to address illegal behaviors with mixed results. In response to jail and prison overcrowding, states have sought to implement more treatment programs for what they categorize as “non-violent” offenders, primarily focusing on drug offenders and those involved in property crimes. As noted earlier, California enacted legislation known as AB 109 Realignment, which shifted the incarceration and supervision of these offenders from state to local authorities, specifically from prison/parole to jail/probation. This shift was based on the belief that local governments could offer more effective treatment options while ensuring public safety. The state provides funding to local governments contingent on their treatment offerings and effectiveness in reducing recidivism. However, compliance with state requirements entails meeting specific objectives and implementing “evidence-based” practices to qualify for this funding.

1.10 Evidence-Based Practices

The National Institute of Corrections defines Evidence-based Practices (EBP) as the objective, balanced, and responsible application of current research and high-quality data to guide policy and practice decisions, ultimately improving outcomes for consumers. Originally applied in healthcare and social sciences, EBP emphasizes methods validated through empirical research, moving beyond anecdotal evidence and personal experiences.

Adopting an evidence-based approach entails ongoing and critical evaluation of research literature to identify trustworthy information, leading to the formulation of the most effective policies and practices based on the best available evidence. It also involves rigorous quality assurance and evaluation to ensure that evidence-based practices are accurately executed and that new practices are assessed for their effectiveness.

In contrast to terms like “best practices” and “what works,” evidence-based practice signifies that 1) there are measurable outcomes; 2) these outcomes can be quantified; and 3) they are defined based on practical realities such as recidivism and victim satisfaction. Though these terms may sometimes be used interchangeably, EBP is especially appropriate for outcome-oriented human service sectors.

This theoretical shift has significantly influenced how correctional facilities and community correction officers approach offender treatment. Agencies are now required not only to demonstrate impact through statistical data but also to implement programs that can positively alter offender behavior. This necessitated the development of new methodologies for evaluating offenders’ risks of reoffending and identifying criminogenic needs. Such tools allow officers to rely not only on their “professional judgment” but also on validated instruments that provide scientific evidence regarding the risk of reoffending. Moreover, these tools assist officers in identifying individuals most likely to reoffend, enabling them to concentrate their supervision and support on these offenders while guiding moderate and low-risk offenders toward more suitable treatment alternatives.

1.11 Developments in the Twentieth Century

Progressives view prisons as essential for achieving two primary goals of the criminal justice system: protecting society from crime and providing a structured environment for offender rehabilitation. They liken prisons to hospitals, where individuals remain until their behavioral issues are addressed. This perspective has led to the concept of an indeterminate sentence, which lasts indefinitely based on the offender’s willingness to engage in rehabilitation. However, due to insufficient funding for training and attracting qualified staff, along with the challenges of managing many individuals with problematic behaviors, the progressive vision for prisons has not been realized. Instead, prisons have become harsh and dehumanizing places that often exacerbate criminal behaviors. Historical analysis indicates that incarceration should be minimized and reserved only for those who pose a clear danger. Furthermore, there is an urgent need to explore alternatives to imprisonment.

The rehabilitation model established in the 1950s emphasizes treatment programs designed to reform offenders. In this framework, ensuring safety during housekeeping activities is essential for successful rehabilitation, as every aspect of the organization must align with rehabilitation objectives. Treatment specialists receive more recognition than other staff. Although many contemporary institutions provide treatment programs, only a handful of prisons continue to follow this model, particularly since the reassessment of rehabilitation goals in the 1970s.

The ‘nothing works’ doctrine suggests that rehabilitation and treatment efforts for criminal offenders largely fail to lower recidivism rates. This contentious theory arose in the 1970s, based on Robert Martinson’s research, which revealed that current programs had minimal success in preventing repeat offenses.

Conclusion

This chapter explores the history and evolution of the corrections system within the United States’ prison framework. As the third pillar of the criminal justice system, it underscores the significance of corrections and its nature. It traces the American foundation of corrections back to the colonial era, when early settlers adopted elements from the British punishment system. The chapter discusses the first U.S. penitentiary, Walnut Street Jail in Philadelphia, and spotlights Louisiana’s correctional history, particularly Angola prison, which was formerly a slave plantation.

It also emphasizes early views on punishment, influenced by religious beliefs, reflecting how early Americans implemented the British approach that prioritized deterring crime through humiliation and corporal punishment. Before the 1800s, common law in countries like the United States relied heavily on physical punishment, but the Age of Enlightenment ignited a transformation in the correctional approach. A pivotal figure in this reform was John Howard, who promoted the penitentiary model. In 1773, the Walnut Street Jail became the first effort to establish a modern European-style penitentiary. Its design featured solitary confinement in small, dark cells, forbidding communication among prisoners. However, opposition to such treatment, alongside issues of overcrowding, prompted the need for reform, leading to the establishment of the Elmira Reformatory in 1876 under Zebulon Broadway’s leadership. The rehabilitation model emerged as a major wave of correctional reform, gaining traction during the 1930s and persisting to the present day.

The chapter outlines the core objectives of the correctional system: deterrence, which aims to diminish or eliminate undesirable behavior through the fear of punishment; incapacitation, wherein criminals are confined to prevent them from victimizing civilians; rehabilitation, focusing on helping offenders avoid reoffending; and retribution, addressing the need to assign punishments that correspond to the harm inflicted by crimes. Furthermore, the chapter highlights the convict leasing system, where businesses negotiate with the state for convict labor. It also examines the racial dimensions and exploitation within Louisiana’s prison system, addressing inequalities and the historical legacy of Louisiana’s prisons alongside modern reforms.

During the 1980s, the prison system experienced significant overcrowding, largely due to mandatory minimum sentencing, three strikes laws, and recidivism. With the development and historical background of the correctional system, this chapter highlights evidence-based practices as an objective balance in the responsible application of research and high-quality data to guide policies and decision-making regarding our modern correctional system. Finally, the chapter closes with developments in the 20th century, discussing some of the different models related to the correctional system, such as the progressive movement and the rehabilitation model, but nothing works model.

Discussion

- Discuss the historical and philosophical approaches to punishment in the development of the correctional system.

- Examine the conditions of the Walnut Street jail, along with solitary confinement and noncommunication between offenders, as compared to today’s prisons.

- Discuss the history of Angola in relation to the convict leasing system.

- Regarding the philosophy of criminal sanctions, describe the goals of the correctional system.

- Describe the history and development of the convict leasing system.

- Discuss prison overcrowding and explain some of the contributing factors.

- What do you see as some advantages and disadvantages of the reformatory movement?

- How has the history of Angola Prison, from its origin as a slave plantation to its role in the convict leasing system, influenced modern prison policies in Louisiana? What lessons can be learned from this history in shaping future prison reforms?

References

Adamson, C. R. (1983). Punishment after slavery: Southern state penal systems, 1865-1890. Social Justice Publications.

Alexander, M. (2012). The new Jim Crow: Mass incarceration in the age of colorblindness. The New Press.

Blackmon, D. A. (2008). Slavery by another name: The re-enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II. Anchor Books.

Logan, C. (1993). Criminal Justice Performance Measures in Prisons. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Lichtenstein, A. (1996). Twice the work of free labor: The political economy of convict labor in the New South. Verso.

McKelvey, B. (1977). American prisons: A history of good intentions. Patterson Smith. Oshinsky, D. M Adamson, C. R. (1983). Punishment after slavery: Southern state penal systems, 1865-1890. Social Problems, 30(5), 555-569.

Pisciotta, A. W. (1994). Benevolent repression: Social control and the American reformatory prison movement. New York University Press.

Rotman, E. (1990). Beyond punishment: A new view on the rehabilitation of criminal offenders. Greenwood Press.

Rothman, D. (1979). For the Good of All – The Progressive Tradition in Prison Reform. National Institute of Justice

Walsh, T. (2016, February 24). How effective are Angola’s reformation methods? NOLA life Stories. Retrieved from NOLA Website.

Media Attributions

- Fig 1.1 is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Fig 1.2 is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Fig 1.3 © “Angola Prison” by msppmoore is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0 is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Fig 1.4 © Joel George

- Fig 1.5 is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Fig 1.7 is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Fig 1.9 is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

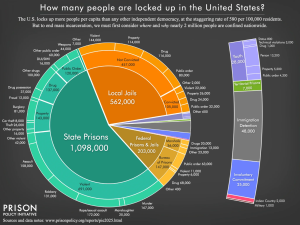

- Fig 1.8 © Prison Policy Initiative - Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie 2025 Article By Wendy Sawyer and Peter Wagner

The first U.S. penitentiary, in Philadelphia, founded in 1773, was designed to reflect the European penitentiary model.

A method where inmates were maintained in solitary confinement within small, dark cells, isolated from communication.

Efforts include altering behavior so that offenders become law-abiding citizens. Prison case managers work with offenders to locate resources available in the community.

Many individuals released from prison found themselves back in custody due to parole infraction or the commission of another crime.

Punishments must be administered with celerity, certainty, and appropriate severity. These elements are based on a type of rational choice theory.

The concept that every individual punished by the law serves as an example for others who might consider the same unlawful act.

It uses punishment as a deterrent to discourage a specific individual from re-offending.

The premise is that when criminals are confined in a secure facility, they are unable to harm ordinary citizens.

Refers to assigning offenders a punishment that corresponds to the harm caused by their crimes.

Imposed life sentences on individuals with three felony convictions

Lawmakers established mandatory minimum sentences for a range of drug offenses.

As the objective, balanced, and responsible application of current research and high-quality data to guide policy and practice decisions, ultimately improving outcomes for consumers.