Chapter 2 – Judicial Process and Sentencing Practices for Misdemeanants, Felons, and Juveniles

Jonathan Sorensen

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, students will be able to:

- Understand Judicial Processing and Sentencing Practices.

- Explore Various types of sentencing and related practices.

- Examine Louisiana’s employment of specific sentencing practices.

Introduction

This chapter covers a range of issues related to judicial processes and sentencing. The importance of presentence investigations and victim impact statements is discussed. Various influences on sentencing are outlined, including aggravating and mitigating circumstances. Different types of sentences are discussed. An historical overview of the death penalty in Louisiana is presented as well as the current statute. The chapter concludes by distinguishing indeterminate, determinate, and mandatory sentencing.

In most jurisdictions, the judge holds the responsibility of imposing criminal sentences on convicted offenders. Often, this is a difficult process that defines the application of simple sentencing principles. The latitude that a judge has in imposing sentences can vary widely from state to state. This is because state legislatures often set the minimum and maximum punishments for particular crimes in criminal statutes. The law also specifies alternatives to incarceration that a judge may use to tailor a sentence to an individual offender.

2.1 – Presentence Investigation

Many jurisdictions require that a presentence investigation take place before a sentence is handed down. Most of the time, the presentence investigation is conducted by a probation officer, and results in a Presentence Investigation Report. This document describes the convict’s education, employment record, criminal history, present offense, prospects for rehabilitation, and any personal issues, such as addiction, that may impact the court’s decision. The report usually contains a recommendation as to the sentence that the court should impose. These reports are a major influence on the judge’s final decision.

After a defendant enters a plea of guilty to a federal offense or is convicted by trial, he or she will meet with a probation officer. Typically, at the initial meeting, the probation officer will conduct an interview with the defendant to gather the following information:

- family history,

- community ties,

- education background,

- employment history,

- physical health,

- mental and emotional health,

- history of substance abuse, financial condition, and

- willingness to accept responsibility for his or her offense(s).

During the presentence investigation, a probation officer will interview other persons who can provide pertinent information, including the prosecutor, law enforcement agents, victims, mental health and substance abuse treatment providers, and the defendant’s family members, associates and employer. The officer will also review numerous documents, which may include, court dockets, indictments, plea agreements, trial transcripts, investigative reports from other law enforcement agencies, criminal history records, counseling and substance abuse treatment records, scholastic records, employment records, and financial records.

Home Visit

When possible, the probation officer conducts a home visit to meet the defendant and the defendant’s family at his/her residence. During the visit, the officer interviews the family and assesses the defendant’s living conditions and suitability for potential supervision conditions, such as location monitoring.

Presentence Report

It is the responsibility of the probation officer assigned to a presentence investigation to assist the court by verifying, evaluating, and interpreting the information gathered, and to present the information to the court in an organized, objective presentence report. Another important part of the preparation of a presentence report involves the probation officer’s investigation into the offense of conviction including the defendant’s involvement, in any similar or uncharged criminal conduct, the impact of the offense on the victim(s), and the sentencing options under the applicable federal statutes and United States Sentencing Guidelines.

The presentence report helps the Court fashion appropriate and fair sentences and is used by probation officers later assigned to supervise the offender. The supervision officer uses the information contained in the presentence report as part of a comprehensive approach to assess risks posed by, and the needs of, offenders under supervision.

The report is also disclosed to the defendant, defense attorney and prosecutor, whom have the opportunity to make objections or seek changes to the presentence report through a formal process established by the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure.

Sentencing

Probation officers conducting the presentence investigation and preparing the presentence report play an integral role in the federal sentencing process.

Although practices differ among the various districts, a probation officer may, at the conclusion of a presentence investigation, work with his or her supervisor to formulate an appropriate sentencing recommendation that will be provided to the court. The officer must be prepared to discuss the case with the sentencing judge, to answer questions about the report that may arise during the Sentencing Hearing, and on rare occasions to testify in court as to the basis for the factual findings and guideline applications set forth in the presentence report.

After sentencing, these presentence reports are utilized by the Bureau of Prisons to designate the institutions appropriate for an offender to serve their sentences, to select prison programs to help the offenders, and to develop case plans for their custody and eventual release. A presentence report is also forwarded to the U.S. Sentencing Commission, which uses the report to monitor the application of the U.S. Sentencing Guidelines and to gather statistics about sentencing trends.

https://www.laep.uscourts.gov/presentence-investigation

2.2 – Victim Impact Statements

Many states now consider a crime’s impact on the victim when determining an appropriate sentence. A few states even allow the victims to appear in court and testify. Victim impact statements are usually read aloud in open court during the sentencing phase of a trial. Criminal defendants have challenged the constitutionality of this process because it violates the Proportionality Doctrine requirement of the Eighth Amendment, but the Supreme Court has rejected this argument and found the admission of victim statements constitutional.

2.3 – The Sentencing Hearing

Many jurisdictions pass final sentences in a phase of the trial process known as a sentencing hearing. The prosecutor will recommend a sentence in the name of the people or defend the recommended sentence in the presentence investigation report, depending on the jurisdiction. Defendants retain the right to counsel during this phase of the process. Defendants also have the right to make a statement to the judge before the sentence is handed down.

Select Link Below for a sample PSI:

Presentence Investigation Report Example

2.4 – Influences on Sentencing Decisions

The severity of a sentence usually hinges on two major factors. The first is the seriousness of the offense. The other, which is much more complex, is the presence of aggravating or mitigating circumstances. In general, the more serious the crime is, the harsher the punishment. Listed below are typical statutory circumstances, which identify the specific criteria for both mitigating and aggravating circumstances.

In the presentence investigation, probation officers prepare a detailed court report that examines the crime, the criminal history of the defendant, the social factors of the defendant and the applicable circumstances in aggravation and mitigation to provide the court (judge) with an objective assessment of the crime and a suitable sentence based on all the indicated factors. It is important to note that a majority of criminal cases are resolved through the plea agreement process, so the range of sentences was agreed upon before the presentence report is prepared.

Aggravating and Mitigating Circumstances Impact on Sentencing:

The aggravating circumstance in the probation report indicates the factors of aggravation that pertain to the crime, or the defendant. Each crime has a sentence triad: a low-term, mid-term, and upper-term. Depending on the weight of the aggravating and mitigating circumstances of the crime and offender, a recommendation will be made in the report to impose one of the three eligible prison terms. The judge will review the report and impose the appropriate sentence based on the totality of circumstances.

Circumstances in Aggravation

Aggravating Factors relating to the crime, whether or not charged or chargeable as enhancements include the following:

- The crime involved great violence, great bodily harm, the threat of great bodily harm, or other acts disclosing a high degree of cruelty, viciousness, or callousness;

- The defendant was armed with or used a weapon at the time of the commission of the crime;

- The victim was particularly vulnerable;

- The defendant induced others to participate in the commission of the crime or occupied a position of leadership or dominance of other participants in its commission;

- The defendant induced a minor to commit or assist in the commission of the crime;

- The defendant threatened witnesses, unlawfully prevented or dissuaded witnesses from testifying, suborned perjury, or in any other way illegally interfered with the judicial process;

- The defendant was convicted of other crimes for which consecutive sentences could have been imposed but for which concurrent sentences are being imposed;

- The manner in which the crime was carried out indicates planning, sophistication, or professionalism;

- The crime involved an attempted or actual taking or damage of great monetary value;

- The defendant took advantage of a position of trust or confidence to commit the offense;

- The crime constitutes a hate crime.

Aggravating Factors relating to the defendant include:

- The defendant has engaged in violent conduct that indicates a serious danger to society;

- The defendant’s prior convictions as an adult or sustained petitions in juvenile delinquency proceedings are numerous or of increasing seriousness;

- The defendant was on probation, mandatory supervision, post-release community supervision, or parole when the crime was committed; and

- The defendant’s prior performance on probation, mandatory supervision, post-release community supervision, or parole was unsatisfactory.

Circumstances in Mitigation

Mitigating Factors relating to the crime:

- The defendant was a passive participant or played a minor role in the crime;

- The victim was an initiator of, willing participant in, or aggressor or provoker of the incident;

- The crime was committed because of an unusual circumstance, such as great provocation, that is unlikely to recur;

- The defendant participated in the crime under circumstances of coercion or duress, or the criminal conduct was partially excusable for some other reason not amounting to a defense;

- The defendant, with no apparent predisposition to do so, was induced by others to participate in the crime;

- The defendant exercised caution to avoid harm to persons or damage to property, or the amounts of money or property taken were deliberately small, or no harm was done or threatened against the victim;

- The defendant believed that he or she had a claim or right to the property taken, or for other reasons mistakenly believed that the conduct was legal;

- The defendant was motivated by a desire to provide necessities for his or her family or self; and

- The defendant suffered from repeated or continuous physical, sexual, or psychological abuse inflicted by the victim of the crime, and the victim of the crime, who inflicted the abuse, was the defendant’s spouse, intimate cohabitant, or parent of the defendant’s child; and the abuse does not amount to a defense.

Mitigating Factors relating to the defendant include:

- The defendant has no prior record, or has an insignificant record of criminal conduct, considering the recency and frequency of prior crimes;

- The defendant was suffering from a mental or physical condition that significantly reduced culpability for the crime;

- The defendant voluntarily acknowledged wrongdoing before arrest or at an early stage of the criminal process;

- The defendant is ineligible for probation and but for that ineligibility would have been granted probation;

- The defendant made restitution to the victim; and

- The defendant’s prior performance on probation, mandatory supervision, post-release community supervision, or parole was satisfactory.

2.5 – Concurrent versus Consecutive Sentences

It is not uncommon for a person to be indicted on multiple offenses. This can be several different offenses, or a repetition of the same offense. In many jurisdictions, the judge has the option to order the sentences to be served concurrently or consecutively. A Concurrent Sentence means that the sentences are served at the same time. A Consecutive Sentence means that the defendant serves the sentences one after another. In Louisiana, sentences for multiple convictions related to the same act are generally served concurrently, while those related to separate acts are generally served consecutively.

Concurrent and consecutive sentences

If the defendant is convicted of two or more offenses based on the same act or transaction, or constituting parts of a common scheme or plan, the terms of imprisonment shall be served concurrently unless the court expressly directs that some or all be served consecutively. Other sentences of imprisonment shall be served consecutively unless the court expressly directs that some or all of them be served concurrently. In the case of the concurrent sentence, the judge shall specify, and the court minutes shall reflect, the date from which the sentences are to run concurrently. (CCRP Art. 883)

2.6 – Types of Sentences

A sentence is the punishment ordered by the court for a convicted defendant. Statutes usually prescribe punishments at both the state and federal level. The most important limit on the severity of punishments in the United States is the Eighth Amendment.

The Death Penalty

The death penalty is a sentencing option in thirty-eight states and the federal government. It is usually reserved for those convicted of murder with aggravating circumstances. Because of the severity and irrevocability of the death penalty, its use has been heavily circumscribed by statutes and controlled by case law. Included among these safeguards is an automatic review by appellate courts.

The death penalty remains a controversial type of correction in the United States [click here to take a virtual tour of San Quentin Prison lethal Injection facility – Look for something similar in Louisiana]. In America, there are many pro and con arguments concerning the death penalty, with educated and qualified individuals on both sides of the debate.

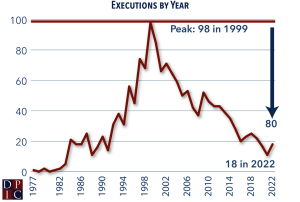

Historically in the United States the death penalty has been imposed for a variety of felonies, from religious infractions to rape, robbery and murder. In 1972, the U.S. Supreme Court held the death penalty to violate the Eighth Amendment due to its often arbitrary and discriminatory imposition (Furman v. Georgia). Since the reimposition of statutes that guide juries’ discretion in assessing punishments relying on aggravating and mitigating factors (see below), only defendants sentenced to death for first-degree murder have been executed. The method of execution has also changed from hanging, gas, and predominantly electrocution to lethal injection. The trend line shows that executions in the modern era peaked at 98 during 1999 and have hovered around 20 annually during the past decade. In line with this trend, President Biden commuted the death sentences of 37 of the 40 inmates under sentences of death in the federal system prior to leaving office.

Historically, in Louisiana, the death penalty was an option for any defendant sentenced to murder at the discretion of the jury before 1972, at which time the U.S. Supreme Court found the death penalty as then imposed unconstitutional throughout the United States (Furman v. Georgia). During that era, Louisiana employed the electric chair, known as “Gruesome Gertie,” which was mobile and traveled from Parish to Parish until 1951. In the case of Francis v. Resweber (1947) the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the death sentence of Willie Francis, a teenager convicted of killing a pharmacist, after a botched execution ruling that the second, and ultimately successful, attempt constituted neither double jeopardy nor cruel and unusual punishment. The last execution in Louisiana occurred in 2010, with the dearth of executions owed mainly to the difficulty in obtaining the drugs used to carry out lethal injections. Governor Landry, however, has pledged to ramp up the executions of inmates remaining on death row with the passage of a law in 2024 allowing for the use of either nitrogen gas or electrocution. Jessie Hoffman became the first inmate executed using this new technology on March 19, 2025 for a murder committed in 1996.

Under the current death penalty statutes, individuals convicted of first-degree murder can be sentenced to death by lethal injection if the jury concludes that one of the following aggravating circumstances was present and outweighs any mitigating circumstances.

The following shall be considered aggravating circumstances:

- The offender was engaged in the perpetration or attempted perpetration of aggravated or first degree rape, forcible or second degree rape, aggravated kidnapping, second degree kidnapping, aggravated burglary, aggravated arson, aggravated escape, assault by drive-by shooting, armed robbery, first degree robbery, second degree robbery, simple robbery, cruelty to juveniles, second degree cruelty to juveniles, or terrorism.

- The victim was a fireman or peace officer engaged in his lawful duties.

- The offender has been previously convicted of an unrelated murder, aggravated or first degree rape, aggravated burglary, aggravated arson, aggravated escape, armed robbery, or aggravated kidnapping.

- The offender knowingly created a risk of death or great bodily harm to more than one person.

- The offender offered or has been offered or has given or received anything of value for the commission of the offense.

- The offender at the time of the commission of the offense was imprisoned after sentence for the commission of an unrelated forcible felony.

- The offense was committed in an especially heinous, atrocious or cruel manner.

- The victim was a witness in a prosecution against the defendant, gave material assistance to the state in any investigation or prosecution of the defendant, or was an eye witness to a crime alleged to have been committed by the defendant or possessed other material evidence against the defendant.

- The victim was a correctional officer or any employee of the Department of Public Safety and Corrections who, in the normal course of his employment was required to come in close contact with persons incarcerated in a state prison facility, and the victim was engaged in his lawful duties at the time of the offense.

- The victim was under the age of twelve years or sixty-five years of age or older.

- The offender was engaged in the distribution, exchange, sale, or purchase, or any attempt thereof, of a controlled dangerous substance listed in Schedule I, II, III, IV, or V of the Uniform Controlled Dangerous Substances Law.

- The offender was engaged in the activities prohibited by R.S. 14:107.1(C)(1).

- The offender has knowingly killed two or more persons in a series of separate incidents. CCRP Art. 905.4

The following shall be considered mitigating circumstances:

- The offender has no significant prior history of criminal activity;

- The offense was committed while the offender was under the influence of extreme mental or emotional disturbance;

- The offense was committed while the offender was under the influence or under the domination of another person;

- The offense was committed under circumstances which the offender reasonably believed to provide a moral justification or extenuation for his conduct;

- At the time of the offense the capacity of the offender to appreciate the criminality of his conduct or to conform his conduct to the requirements of law was impaired as a result of mental disease or defect or intoxication;

- The youth of the offender at the time of the offense;

- The offender was a principal whose participation was relatively minor;

- Any other relevant mitigating circumstance. CCRP Art. 905.5

Incarceration

The most common punishment after fines in the United States is the deprivation of liberty known as Incarceration. Jails are short-term facilities, most often run by counties under the auspices of the sheriff’s department. Jails house those awaiting trial and unable to make bail, and convicted offenders serving short sentences or waiting on a bed in a prison. Prisons are long-term facilities operated by state and federal governments. Most prison inmates are felons serving sentences of longer than one year.

Probation

Probation serves as a middle ground between no punishment and incarceration. Convicts receiving probation are supervised within the community and must abide by certain rules and restrictions. If they violate the conditions of their probation, they can have their probation revoked and can be sent to prison. Common conditions of probation include obeying all laws, paying fines and restitution as ordered by the court, reporting to a probation officer, not associating with criminals, not using drugs, submitting to searches, and submitting to drug tests.

The heavy use of probation is controversial. When the offense is nonviolent, the offender is not dangerous to the community, and the offender is willing to make restitution, then many agree that probation is a good idea. Due to prison overcrowding, judges have been forced to place more and more offenders on probation rather than sentencing them to prison.

Intensive Supervision Probation (ISP)

Intensive Supervision Probation (ISP) is similar to standard probation but requires much more contact with probation officers and usually has more rigorous conditions of probation. The primary focus of adult ISP is to provide protection of public safety through close supervision of the offender. Many juvenile programs, and an increasing number of adult programs, also have a treatment component that is designed to reduce recidivism.

[insert figure 2.2]

Boot Camps

Convicts, often young men, sentenced to boot camps live in a military-style environment complete with barracks and rigorous physical training. These camps usually last from three to six months, depending on the particular program. The core idea of boot camp programs is to teach wayward youths discipline and accountability. While a popular idea among some reformers, the research shows little to no impact on recidivism.

House Arrest and Electronic Monitoring

The Special Curfew Program was the federal courts’ first use of home confinement. It was part of an experimental program, a cooperative venture of the Bureau of Prisons, the U.S. Parole Commission, and the federal probation system, as an alternative to the Bureau of Prisons Community Treatment Center (CTC) residence for eligible inmates. These inmates, instead of CTC placement, received parole dates advanced a maximum of 60 days and were subject to a curfew and minimum weekly contact with a probation officer. Electronic Monitoring became part of the home confinement program several years later.

[INSERT FIGURE 2.3]

In 1988, a pilot program was launched in two districts to evaluate the use of electronic equipment to monitor persons in the curfew program. The program was expanded nationally in 1991 and grew to include offenders on probation and supervised release and defendants on pretrial supervision, as those who may be eligible to be placed on home confinement with electronic monitoring (Courts, 2015).

Today, most jurisdictions stipulate that offenders sentenced to house arrest must spend all or most of the day in their own homes. The popularity of house arrest has increased in recent years due to monitoring technology that allows a transmitter to be placed on the convict’s ankle, allowing compliance to be remotely monitored. House arrest is often coupled with other sanctions, such as fines and community service. Some jurisdictions have a work requirement, where the offender on house arrest is allowed to leave home for a specified window of time in order to work.

[INSERT FIGURE 2.4]

Fines

Fines are very common for violations and minor misdemeanor offenses. First-time offenders found guilty of simple assaults, minor drug possession, traffic violations, and so forth are sentenced to fines alone. If these fines are not paid according to the rules set by the court, the offender is jailed. Many critics argue that fines discriminate against the poor. A $200 traffic fine means very little to a highly paid professional but can be a serious burden on a college student with only a part-time job. Some jurisdictions use a sliding scale that bases fines on income, known as Day Fines. They are an outgrowth of traditional fining systems, which were seen as disproportionately punishing offenders with modest means while imposing no more than “slaps on the wrist” for affluent offenders.

This system has been very popular in European countries such as Sweden and Germany. Day fines take the financial circumstances of the offender into account. They are calculated using two major factors: The seriousness of the offense and the offender’s daily income. The European nations that use this system have established guidelines that assign points (“fine units”) to different offenses based on the seriousness of the offense. The range of fine units varies greatly by country. For example, in Sweden, the range is from 1 to 120 units. In Germany, the range is from 1 to 360 units. The most common process is for court personnel to determine the daily income of the offender. It is common for family size and certain other expenses to be taken into account.

Restitution

When an offender is sentenced to a fine, the money goes to the state. Restitution requires the offender to pay money to the victim. The idea is to replace the economic losses suffered by the victim because of the crime. Judges may order offenders to compensate victims for medical bills, lost wages, and the value of property that was stolen or destroyed. The major problem with restitution is actually collecting the money on behalf of the victim. Some jurisdictions allow practices such as wage garnishment to ensure the integrity of the process. Restitution can also be made a condition of probation, whereby the offender is imprisoned for a probation violation if the restitution is not paid.

Community Service

As a matter of legal theory, crimes harm the entire community, not just the immediate victim. Advocates see Community Service as the violator paying the community back for the harm caused. Community service can include a wide variety of tasks such as picking up trash along roadways, cleaning up graffiti, and cleaning up parks. Programs based on community service have been popular, but little is known about the impact of these programs on recidivism rates.

[INSERT FIGURE 2.5]

“Scarlet-letter” Punishments

While exact practices vary widely, the idea of scarlet-letter punishments is to shame the offender. Advocates view shaming as a cheap and satisfying alternative to incarceration. Critics argue that criminals are not likely to mend their behavior because of shame. There are legal challenges that have kept this sort of punishment from being widely accepted. Appeals have been made because such punishments violate the Eighth Amendment ban on cruel and unusual punishment. Others have been based on the idea that they violate the First Amendment by compelling defendants to convey a judicially scripted message in the form of forced apologies, warning signs, newspaper ads, and sandwich boards.

Still other appeals have been based on the notion that shaming punishments are not specifically authorized by State sentencing guidelines and therefore constitute an abuse of judicial discretion (Litowitz, 1997).

2.7 – Asset Forfeiture

Many jurisdictions have laws that allow the government to seize property and assets used in criminal enterprises. Such a seizure is known as forfeiture. Automobiles, airplanes, and boats used in illegal drug smuggling are all subject to seizure. The assets are often given over to law enforcement. According to the FBI, “Many criminals are motivated by greed and the acquisition of material goods. Therefore, the ability of the government to forfeit property connected with criminal activity can be an effective law enforcement tool by reducing the incentive for illegal conduct. Asset forfeiture takes the profit out of crime by helping to eliminate the ability of the offender to command resources necessary to continue illegal activities” (FBI, 2015).

Asset Forfeiture can be both a criminal and a civil matter. Civil forfeitures are easier on law enforcement because they do not require a criminal conviction. As a civil matter, the standard of proof is much lower than it would be if the forfeiture were a criminal penalty. Commonly, the standard for such a seizure is probable cause. With criminal asset forfeitures, law enforcement cannot take control of the assets until the suspect has been convicted in criminal court.

2.8 – Appeals

An appeal is a claim that some procedural or legal error was made in the prior handling of the case. An appeal results in one of two outcomes. If the appellate court agrees with the lower court, then the appellate court affirms the lower court’s decision. In such cases, the appeals court is said to uphold the decision of the lower court. If the appellate court agrees with the plaintiff that an error occurred, then the appellate court will overturn the conviction. This happens only when the error is determined to be substantial. Trivial or insignificant errors will result in the appellate court affirming the decision of the lower court. Winning an appeal is rarely a “get out of jail free” card for the defendant. Most often, the case is remanded to the lower court for rehearing. The decision to retry the case ultimately rests with the prosecutor. If the decision of the appellate court requires the exclusion of important evidence, the prosecutor may decide that a conviction is

2.9 – Sentencing Statutes and Guidelines

In the United States, most jurisdictions hold that criminal sentencing is entirely a matter of statute. That is, legislative bodies determine the punishments that are associated with particular crimes. These legislative assemblies establish such sentencing schemes by passing sentencing statutes or establishing sentencing guidelines. These sentences can be of different types that have a profound effect on both the administration of criminal justice and the life of the convicted offender.

[INSERT FIGURE 2.6]

2.10 – Indeterminate Sentences

An Indeterminate Sentence is a type of criminal sentencing where the convict is not given a sentence of a certain period in prison. Rather, the amount of time served is based on the offender’s conduct while incarcerated. Most often, a broad range is specified during sentencing, and then a parole board will decide when the offender has earned release.

For much of the twentieth century, statutes commonly allowed judges to sentence criminals to imprisonment for indeterminate periods. Under this indeterminate sentencing approach, judges sentenced the offender not to a specific period of time but rather to a time frame that was often quite broad (ex. 5 to 25 years). For an offender given an indeterminate prison sentence, release – at 5 years, 10 years, or any period short of the maximum sentence – was contingent upon getting paroled or approved for release by a parole board which determined that the person was rehabilitated.

Because some offenders might rapidly show signs of reform, while others appeared resistant to change, indeterminate sentencing’s open-ended time frame was deemed optimal for allowing individual rehabilitation, no matter how quickly or slowly. In other words, an indeterminate sentence functioned almost like an individualized “treatment plan,” which was flexible to the needs of the offender. Moreover, the promise of release at the early end or minimum sentence was thought to function as an incentive for “good behavior” and participation in rehabilitative programming.

Yet, skepticism around indeterminate sentencing began to brew in the late 20th century, with critics highlighting both its ineffectiveness and potential for abuse. Indefinite sentences give tremendous discretion and power to judges, parole boards, and prison officials who inform parole decisions. Inmates who were unpopular with correctional officers or wardens, due to their political beliefs, religion, or race, had little hope of a favorable parole recommendation. Moreover, as crime ticked upward in the late 1960s and 1970s, many began to wonder if indeterminate sentences reformed or merely empowered “unfixable” offenders. In many ways, the end of indeterminate sentencing signaled the origins of mass incarceration in the United States. While many states began to abandon indeterminate sentencing (in favor of determinate sentencing), in the 1970s and 1980s, the federal government legally ended parole for federal prisoners in the 1984 Comprehensive Crime Control Act (CCCA). After the CCCA took effect in 1987, any individual sentenced to federal prison was required to serve at least 85% of their sentence, with (slightly) early release predicated upon the banking of “good time” – not parole.

2.11 – Determinate Sentences

A Determinate Sentence is of a fixed length and is generally not subject to review by a parole board. Convicts must serve the entire sentence, minus any good time earned while incarcerated.

Under determinate sentencing, judges have little discretion in sentencing. The legislature sets specific parameters on the sentence (ex. 36 to 41 months), and the judge sets a fixed term of years (or months) within that time frame (ex. 38 months). Often, such sentencing laws allow the court to increase the term (beyond the given window) if it finds aggravating factors and reduce the term (below the given window) if it finds mitigating factors. With determinate sentencing, the defendant knows immediately when he or she will be released. While determinate sentencing does not allow for parole, there may be some options for early release; namely, offenders may receive credit for time served while in pretrial detention, or “good time” credits for good behavior while incarcerated. The discretion that judges are allowed in initially setting the fixed term is what distinguishes determinate sentencing from definite sentencing.

Determinate sentencing grew largely out of growing disenchantment with indeterminate sentencing and, more broadly, the “rehabilitative ideal” in sentencing and incarceration. Multiple books and research papers published in the 1970s asserted that rehabilitative programs in prisons simply weren’t working; moreover, indeterminate sentences created great disparities between offenders convicted of similar crimes and further caused inmates unnecessary stress and anxiety. These critiques combined with growing concerns over crime, which were embraced by politicians promoting a “get tough” approach. Ironically, there is little evidence that the move toward determinate sentencing significantly improved sentencing inequities or prisoners’ attitudes toward prison and their sentences. Yet this approach – in combination with “innovations” such as sentencing guidelines, mandatory minimums, and sentencing enhancements, continues to drive much state and federal sentencing.

2.12 – Mandatory Sentences

Mandatory sentences are a type of sentence where the absolute minimum sentence is established by a legislative body. This effectively limits judicial discretion in such cases. Mandatory sentences are often included in habitual offender laws, such as repeat drug offenders. Under federal law, prosecutors have the powerful plea-bargaining tool of agreeing not to file under the prior felony statute.

2.13 – Sentencing Guidelines

Legislative enactments, ballot measures, initiatives, and referendums have resulted in mandatory minimum sentencing schemes, in which offenders who commit certain crimes must be sentenced to prison terms for minimum periods. Mandatory minimum sentences take precedence over, but do not completely replace, whatever other statutory or administrative sentencing guidelines may be in existence. It is possible for a judge to impose a sentence that exceeds the mandatory minimum, following their judgment that an offender warrants a particularly harsh guideline sentence due to their criminal history or the brutality of their crime; however, judges may not impose a sentence lower than the mandatory minimum.

Mandatory minimum sentences are a type of determinate sentence. At the state level, most mandatory minimum sentences are attached to violent offenses or offenses involving the use of firearms. Federal law also mandates minimum prison terms for certain drug crimes prosecuted in federal courts. For example, a person charged with possession with the intent to distribute more than five kilograms of cocaine, or 0.28 kilograms of crack cocaine, is subject to a mandatory minimum sentence of ten years in prison (See, 21 U.S.C.A. §841 (b)(1)(A)). Indeed, the severe mandatory minimums – and unjustified, racialized disparities – for federal drug offenses have driven a growing outcry against mandatory minimum sentencing schemes, which have not been shown to reduce sentencing disparities or offender recidivism.

Louisiana Mandatory Minimums: Louisiana state law has in place mandatory minimum sentences for some nonviolent drug offenses that equate to distribution or cultivation of schedule I drugs. Read LA Revised Statute 40:966 – “Penalty for distribution or possession with intent to distribute” to learn more about mandatory minimums in Louisiana.

The Sentencing Reform Act of 1984 was passed in response to congressional concern about fairness in federal sentencing practices. The Act completely changed the way courts sentenced federal offenders. The Act created a new federal agency, the U.S. Sentencing Commission, to set sentencing guidelines for every federal offense. When federal sentencing guidelines went into effect in 1987, they significantly altered judges’ sentencing discretion, probation officers’ preparation of the presentence investigation report, and officers’ overall role in the sentencing process. The new sentencing scheme also placed officers in a more adversarial environment in the courtroom, where attorneys might dispute facts, question guideline calculations, and object to the information in the presentence report. In addition to providing for a new sentencing process, the Act also replaced parole with “supervised release,” a term of community supervision to be served by prisoners after they completed prison terms (Courts, 2015).

When the Federal Courts began using sentencing guidelines, about half of the states adopted the practice. Sentencing guidelines indicate to the sentencing judge a narrow range of expected punishments for specific offenses. The purpose of these guidelines is to limit judicial discretion in sentencing. Several sentencing guidelines use a grid system, where the severity of the offense runs down one axis, and the criminal history of the offender runs across the other. The more serious the offense, the longer the sentence the offender receives. The longer the criminal history of the offender, the longer the sentence imposed. Some systems allow judges to go outside of the guidelines when aggravating or mitigating circumstances exist.

The Sentencing Reform Act of 1984 also established the United States Sentencing Commission, which is an independent agency in the judicial branch of the government. Its mission is to provide the federal courts with guidelines for appropriate punishment of crimes, to establish the development of effective and efficient crime policy, and to provide data, and research regarding criminal justice issues and provide their findings to the other branches of government and the public.

The drastic increase in the prison population has become a greater concern for government agencies and policymakers. The rising costs of prisons and questions regarding fair treatment of inmates have led agencies such as the United States Sentencing Commission to seek answers on how to protect the community but addressing the concerns regarding the high rate of incarceration in the United States. Sentencing reform began with the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010. It sought to reduce the disparity of sentences for crack cocaine. It eliminated the mandatory minimum sentence of five years for possession of crack cocaine. In 2018, the First Step Act was signed into law by President Trump. This reform has two goals: first, to cut the length of non-violent criminal offenses such as drug crimes, and to reduce recidivism rates through the use of evidence-based rehabilitation programs. The bill has several provisions:

- It will make the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010 retroactive.

- Ease the mandatory minimum sentence guidelines and provide the judicial branch with more discretion in sentencing.

- It increases the “good time credits” that inmate can earn while serving their sentences.

- It provides more “good time credits” for offenders who participate in vocational training or rehabilitation programs while incarcerated.

Conclusion:

In most jurisdictions, judges hold responsibility for imposing criminal sentences on convicted offenders. The type and range of allowable sentences are determined within the bounds set by statutes passed by legislatures. Most commonly, convicted offenders are sentenced either to a term of probation or imprisonment. In choosing from the range of available alternatives, judges rely on information concerning the defendant’s history revealed by the presentence investigation as well as the types of aggravating and mitigating factors involved in their crimes. Those sentenced to probation often receive additional intermediate sanctions ranging from participation in particular programs and monetary sanctions up to house arrest. Those sentenced to prison may receive sentences of determinate length reduced only through the accumulation of good time, while others receive sentences of indeterminate length, with their ultimate date of release from prison being determined by a parole board.

Discussion

What types of sentences and sentencing practices promote the greatest degree of fairness? In what ways?

Media Attributions

This document, compiled by a probation officer, describes the convict's education, employment record, criminal history, present offense, prospects for rehabilitation, and any personal issues, such as addiction, which be useful to the court in making an appropriate sentencing decision.

The final phase of the trial process wherein the judge determines the appropriate sentence to be served by a defendant.

The requirement that a criminal punishment be commensurate with the degree of the harm caused by the crime committed.

For defendants who are sentenced for multiple crimes, their sentences are to be served at the same time.

For defendants who are sentenced for multiple crimes, their sentences are to be served one after the other.

A sentence involving the deprivation of liberty in jail or prison.

A sentence wherein convicted criminals are supervised within the community and must abide by certain rules and restrictions.

A stipulation whereby accused or convicted criminals serving their time under house arrest wear an electronic bracelet to enforce the terms of their confinement.

Fines utilized in some jurisdictions which rely on a sliding scale that bases the amount of fines on a defendant’s income in daily increments.

A sentence whereby a violator pays the community back for the harm caused by completing any of a wide variety of tasks.

Laws that allow the government to seize property and assets obtained as a result of criminal enterprises.

A type of criminal sentencing wherein the amount of time served by a convict is based on the offender's conduct while incarcerated and release determined by the parole board.

A sentence of fixed length that is generally not subject to review by a parole board.

An act passed by Congress that significantly changed the way that convicted criminals were sentenced in the federal courts by narrowing and channeling judges’ sentencing discretion.

An Act passed by Congress that reduced the disparity of sentences for crack cocaine by eliminating the mandatory minimum sentence of five years for possession.