Chapter 3 – The Correctional Offender & Special Needs Population

Geraldine Doucet

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, students will be able to:

- Identify and describe the diverse populations served within correctional institutions.

- Compare and contrast the characteristics and experiences of male and female prisoners.

- Explain the purpose and process of offender classification and reclassification within correctional systems.

- Summarize the characteristics and needs of special populations within prison settings (e.g., juveniles, mentally ill, elderly, LGBTQ+).

- Analyze the historical and contemporary approaches to managing correctional offenders in the State of Louisiana.

- Explain major correctional ideologies and their influence on contemporary correctional practices.

Introduction

“Education is the most powerful weapon you can use to change the world.” – Nelson Mandela

Nelson Mandela, who once endured incarceration, powerfully reminded the world that education is the most powerful tool for change. His words hold special meaning in the field of corrections, where humane, evidence-based, and rehabilitative practices can truly transform lives. Understanding the correctional client, that is the people under supervision or custody of correctional systems, is crucial for developing policies and practices that foster personal growth, ensure public safety, and support successful reentry into society.

Globally, correctional systems are responsible for overseeing diverse offender populations with a wide range of risks, needs, and behavioral characteristics (Doucet & Adu-Frimpong, 2025). This chapter examines the complex landscape of correctional clients, exploring distinctions between male and female offenders, the principles and practices of classification and reclassification, and the challenges gangs, and those faced by both general and special-needs populations.

While the previous chapters introduced correctional history, ideologies, and the role of judiciary, this chapter shifts focus specifically to the offender population. Over the past thirty years, scholars and practitioners have described correctional offenders in multiple ways: by type of offense (misdemeanor or felony), offense category (violent or property), custody status (incarcerated or on community supervision), or by specialized categories such as gang-affiliated, terrorist, or habitual offenders, etc. In addition, the term “special needs” offenders capture a growing and diverse subgroup with distinct challenges.

The chapter proceeds in six parts: (1) male and female offenders, (2) classification and reclassification, (3) gangs in prison, (4) offender population, (5) special populations, and (6) Louisiana’s approaches to managing offenders. It begins with exploration of male and female offenders, who often enter the system with different backgrounds, criminal behaviors, and rehabilitative needs. These differences influence security measures, treatment options, and facility design. The chapter then turns to classification and reclassification processes, which are essential for placing offenders in the right security level, housing, and programming. Accurate classification helps protect staff and inmates, promotes institutional safety, and supports rehabilitation. Next, the chapter explores special populations within corrections, including juvenile offenders housed in adult facilities, sexual offenders, substance abusers, offenders with disabilities, elderly offenders, pregnant women, LGBTQ+ individuals, veterans, immigrants, and those with mental illness. These groups require specialized services and accommodations to ensure humane treatment, legal protections, and ethical standards. Finally, the chapter highlights the State of Louisiana’s approaches to managing its correctional offender population over time.

3.1: Landscape of Correctional Clients

In this chapter, “correctional offenders” or “correctional clients” will be defined broadly, including those housed in incarcerated facilities (jails, prisons, detention centers) and those supervised in community settings (probation, parole, or other reentry programs). Within jails, individuals might be awaiting trial, convicted, detained, or held for protective reasons, and may be referred to as arrestees, inmates, or detainees. Those in prisons are often described as prisoners, inmates, offenders, or “incarcerated individuals.” Juvenile offenders in the system are often labeled “delinquents,” however, those committing status offenses are not the focus of this chapter. For adult community-based corrections, the terms probationers, parolees, or releasees apply, as does the increasingly common phrase “formerly incarcerated persons.” For the purposes of this chapter, “offenders” will encompass all these categories.

The correctional population is highly diverse demographically, by gender (i.e., consisting of men and women; age (i.e., juveniles, elderly), race, mentally and physically status, as well as a host with special needs (Clear, Reisig, & Cole, 2021; Meyer, 2015; Maschi, Viola, & Koskinen, 2015; Mears, 2010; James & Glaze, 2006).

Demographics: Incarcerated individuals vary significantly across gender, age, and race. Women in custody are more likely to have trauma histories, mental health issues, or caregiving responsibilities, requiring gender-responsive programming (Covington & Bloom, 2007). Juvenile offenders also need developmentally appropriate interventions (Underwood & Washington, 2016).

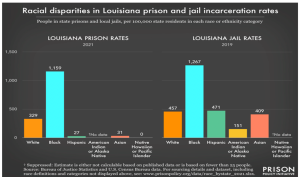

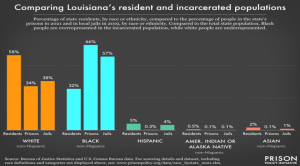

Racial Disparities: Black and Hispanic individuals remain disproportionately represented. Black men are imprisoned at 5.5 times the rate of White men; Black women at 1.6 times the rate of White women (Mistrett, M. & Espinoza, M. (2021). Though Black and Latinx people make up 30% of the U.S. population, they account for over half the jail population (National Conference of State Legislatures -NCSL, 2022).

Health and Special Needs

Many offenders enter the system with untreated mental illness, substance use disorders, or chronic diseases such as hypertension, diabetes, and HIV/AIDS (James & Glaze, 2006; Maruschak et al., 2015). These conditions strain correctional healthcare systems and heighten the need for reform.

Certain groups face unique risks:

- LGBTQ+ individuals are more vulnerable to harassment and sexual assault and often lack culturally competent care (Meyer, 2015; Beck et al., 2014).

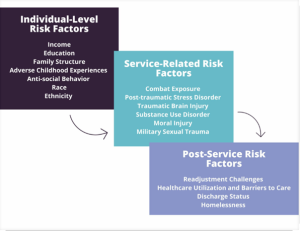

- Veterans may experience PTSD or service-related conditions requiring specialized treatment (Tsai, Mares, & Rosenheck, 2012).

- Elderly inmates increasingly require geriatric care, accessible housing, and end-of-life services due to longer sentences and aging demographics (Maschi, Viola, & Koskinen, 2015).

- Disabled individuals need accommodations such as accessible facilities and trained staff.

Importance of Recognition

Acknowledging the diversity of correctional clients is essential for effective classification, risk assessment, and programming. Tailored strategies enhance safety, uphold constitutional rights, reduce recidivism, and support reintegration (Taxman et al., 2007).

Scale of Corrections

As of 2025, about 2 million people were incarcerated in the U.S. across state and federal prisons, local jails, juvenile facilities, immigration detention centers, tribal facilities, military prisons, and psychiatric hospitals. These figures underscore the scope and variety of today’s correctional population.

Correctional systems regardless of size and diversity are responsible for addressing these varied needs through structured interventions such as classification systems, specialized housing, rehabilitative programs, and reentry planning (Latessa & Smith, 2011). Jail and prison infirmaries play a vital role in treating and caring for individuals with complex health needs. Ultimately, special populations in corrections require careful, thoughtful management to ensure humane, legal, and effective treatment.

The next section will focus on male and female offender populations.

3.2: Men and Women in Prison: A Gendered Landscape

In spring 2024, about 1.8 million people were incarcerated in the United States. While the system is overwhelmingly male-dominated, women remain the fastest-growing segment of the prison population. Between 2024 and 2025, the number of men incarcerated dropped by more than 5%, while the decline for women was less than 1% (BJS, 2025; Prison Policy Initiative, 2025). Since 1978, however, women’s imprisonment rates have risen far more rapidly than men’s.

Male Offenders

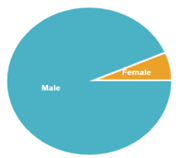

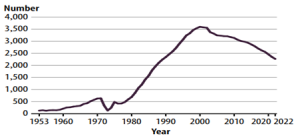

Men account for about 93.5% of the prison population, or over 1.1 million people as shown in Figures 3.2.1 and 3.2.2 below, which illustrates the number and percentage men and women in prison as recent as June 2025. Most male inmates are incarcerated for violent or drug-related crimes, often with gang involvement or offenses committed under the influence of drugs or alcohol (Beck, 1990; Council on Criminal Justice, 2024).

Poverty, homelessness, and policy shifts that criminalize social problems have also contributed to high incarceration rates, particularly among men of color. Other characteristics include:

- Disproportionately Black (34.9%) or Hispanic (30.7%).

- Average age is 42; nearly one in four is over 50.

- Many lack a high school diploma and have prior criminal history.

- Offenses often include murder, aggravated assault, sex offenses, and property crimes.

Male inmates’ needs often revolve around vocational training, aggression management, and reentry preparation.

Female Offenders

As shown in Figure 3.2.2-above, women make up only 6.5% of the prison population (about 174,600 in 2025), yet their incarceration rate has grown nearly twice as fast as men since 1980 (Budd, 2024). Currently, the United States imprisons more women than any other country (World Prison Brief, 2025). Here are some other significant trends:

- Women’s state prison populations grew 834% between 1980 and 2020, compared to 367% for men.

- Women are more likely than men to be held in jails, where high bail costs keep many detained pretrial (Sawyer, 2028).

- Mental health concerns are acute: one in three jailed women reports serious psychological distress.

Patterns of Crime:

- Women commit fewer violent crimes than men.

- About 70% of women’s offenses are property crimes, compared to 50% for men.

- Drug crimes and misdemeanors are also common.

Characteristics:

- Black women are imprisoned at 1.6 times the rate of White women; Latina women at 1.2 times (Budd, 2024).

- About 62% are mothers of children under 18, compared to 51% of incarcerated men.

- Over 12,000 women enter prison pregnant each year, raising health and caregiving concerns.

Women’s needs differ significantly from men’s. They face greater challenges related to trauma, reproductive health, and parenting. Correctional systems increasingly emphasize trauma-informed care, gender-specific mental health treatment, parenting programs, and nursery initiatives (Covington, 2007).

Conclusion

Men continue to make up the overwhelming majority of inmates, mostly for violent crimes, while women are more often incarcerated for property or drug offenses. Women, however, face greater struggles with health, trauma, and family responsibilities, highlighting the need for gender-responsive, evidence-based correctional strategies.

Table 3.2.3 – Summary Characteristics of Male and Female Offenders

| Category | Men | Women |

| Proportion of prison population (2025) | 93.5% | 6.5% |

| Most common offenses | Violent crimes, drug trafficking, gang activity | Property crimes, drug possession, some violent crimes |

| Average age | 42 (22.5% aged 50+) | 39 |

| Major needs | Vocational training, aggression management | Trauma-informed care, mental health, parenting support |

| Parental status | 51% are parents of children under 18 | 62% are parents of children under 18 |

Source: Bureau of Justice Statistics (2025); Prison Policy Initiative (2025).

Discussion Questions

- Discuss your thoughts about whether female offenders be allowed to have their children under age two stay with them in prison?

- Why do you think the male prison population is so much larger than the female prison population?

3.3: Classification: Offenders and Institution

Purpose of Classification

Classification is a core element of correctional administration. It matches inmates’ risks and needs with housing, custody levels, and rehabilitative programming (Snarr & Wolford, 1985). The National Advisory Commission on Corrections-UNODC (2020; Moser, 2020), maintains that classification serves two primary purposes once prisoners are placed into custody or supervision levels that fit their risks and needs.

Classification serves two purposes:

- Assessing individual offender needs.

- Matching those needs with institutional programs and services.

Both functions directly affect inmates’ daily lives and opportunities for rehabilitation.

Institutional Security Levels

Most state prisons operate at minimum, medium, and maximum security:

- Minimum: Dormitory housing, limited fencing, educational or work release opportunities.

- Medium: Double fencing, controlled movement, structured programming.

- Maximum: High-risk offenders, reinforced security, intensive monitoring.

The Federal Bureau of Prisons uses five levels: minimum, low, medium, high (maximum), and administrative, with distinctions based on supervision, staff ratios, and medical or mental health care availability.

The Classification Process

Classification begins at intake, where inmates undergo:

- Medical and mental health screenings

- Risk assessment tools

- Criminal history and institutional behavior reviews

- Interviews and psychosocial evaluations

This determines custody level, housing, and access to programs such as vocational training, education, and behavioral interventions.

Historical Development

Early systems in Europe and the U.S. often separated inmates by age, gender, or offense type. The Pennsylvania model emphasized solitary confinement, while the Auburn model stressed strict discipline and labor. By the mid-19th century, humanitarian and rehabilitative goals led to more sophisticated classification practices (Silverman & Vega, 1996).

Reclassification

Classification is ongoing. Reclassification adjusts custody levels based on program participation, behavior, or disciplinary issues (Hardyman et al., 2004). Reviews occur every 6–12 months or after major incidents.

- Custody reductions reward positive behavior and program completion.

- Custody increases follow disciplinary violations, aggression, or escape attempts.

This dynamic process promotes fairness, safety, and rehabilitation.

Juvenile Classification

Juvenile systems adapt classification to emphasize developmental needs and rehabilitation. Key steps include:

- Assessing community risk.

- Determining treatment needs.

- Regular reclassification based on progress.

Modern approaches include psychological evaluations, standardized risk tools, and due process protections, since classification can affect liberty interests Such as parole eligibility or restrictive housing.

Conclusion

Classification is the backbone of correctional operations. It shapes institutional safety, access to services, and prospects for rehabilitation. Through evidence-based and dynamic assessments, classification systems support security while advancing correctional reform, reentry, and public safety.

Discussion Questions

- Define the basic elements of prison classification. Contrast the differences between prison classification versus offender classification?

- Discuss your understanding of institutional classification system by examining factors that influence Offender classification decisions.

3.4: Gangs in Prison

Prison gangs, officially called Security Threat Groups (STGs), pose a persistent and complex challenge to correctional facilities and public safety in the United States. The presence of these groups in jails and prisons has a profound impact on institutional life, affecting inmate safety, the prison culture, and daily operations. While jails tend to house individuals for shorter periods, prisons — with their longer sentences — face a more sustained threat from gangs.

In correctional settings, a gang refers to an organized group of inmates engaged in criminal activities, such as drug trafficking, extortion, or violence, both inside and outside prison walls. Because of their coordinated and often violent nature, gangs are formally labeled security threat groups or disruptive groups (Snarr & Wolford, 1985). These groups significantly undermine efforts at rehabilitation, institutional security, and order.

Compared to street gangs, prison gangs have received less research attention from criminologists, sociologists, and psychologists (Gundur, 2020). Yet their impact is considerable. Prison gangs often function as organized criminal enterprises with complex structures, rules, and codes of loyalty. Activities may include drug smuggling, extortion, human trafficking, and even contract killings. Each gang typically maintains its own symbols, mottos, colors, and even a constitution to reinforce loyalty and control (Gundur, 2020; Kristine & Chambliss, 2011).

Prison gangs tend to be more hierarchical and stable than street gangs, with leadership structures that remain intact over long periods. In contrast, street gangs often have more fluid, loosely organized leadership, with shifting alliances and opportunistic crimes (Gundur, 2020). Both types, however, demand absolute loyalty and secrecy from their members. In this sense, prison gangs resemble organized crime networks — though even more sophisticated organized offenders will be discussed later in the chapter.

As of 2023, nearly 20% of incarcerated individuals in the U.S. were affiliated with some form of gang (Zeng, 2025), highlighting the widespread influence of these groups. Their power extends beyond prison walls, with ties to street gangs and telecommunication networks that allow them to recruit, intimidate, and coordinate criminal activities across communities.

Historical Context and Major Prison Gangs

Some of the earliest and most notorious prison gangs developed in California during the civil rights era, when rising racial tensions and inmate safety concerns contributed to gang formation. For example:

- Aryan Brotherhood (AB): Originating in San Quentin in the 1960s, initially organized for racial protection but evolved into a violent crime syndicate involved in drug smuggling, extortion, and murder.

- Black Guerrilla Family (BGF): Also founded in San Quentin in the 1960s, with an ideological Marxist-Leninist mission to combat oppression within the prison system.

- La Nuestra Familia (NF): Formed in the 1960s in Northern California to protect rural and working-class Hispanic inmates, becoming rivals to the Mexican Mafia.

- Mexican Mafia (La Eme): Established in 1957 at Deuel Vocational Institution, this powerful and violent gang controls many Southern California Hispanic street gangs (Sinclair, 2023).

In Texas, several major prison gangs have been identified by the Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ), including:

- Texas Syndicate: Originally formed in California but made up largely of Texas inmates, known for strict loyalty rules and involvement in drug smuggling.

- Barrio Azteca: Closely linked with Mexican drug cartels, conducting contract killings and coordinating cross-border crime.

- Tango Blast: Notorious for its loosely organized, city-based network, making it difficult for law enforcement to control. As of 2017, estimates put its membership at over 8,200 (Texas Department of Public Safety, 2017).

The racial and ethnic backgrounds of prison gangs often mirror the communities from which inmates come. As a result, gang networks are reinforced both inside facilities and in their home communities (Kristine & Chambliss, 2011).

Correctional Responses to Prison Gangs

Correctional systems have developed various strategies to respond to the threats posed by prison gangs. These include:

- Intelligence gathering through informants and surveillance.

- Isolation strategies such as administrative segregation (solitary confinement).

- Transfer of gang leaders to disrupt organizational structures.

- Rehabilitation programs focused on disengaging inmates from gang culture.

In Texas, the Security Threat Group Management Office (STGMO) is responsible for identifying and monitoring gang members through investigations and intelligence networks. Once validated as a gang member, an inmate is often moved to administrative segregation to disrupt their influence and protect others.

However, ethical and mental health concerns about prolonged isolation have prompted alternatives. For example, Texas developed the Gang Renouncement and Disassociation (GRAD) process, a phased program including debriefing, counseling, education, and behavior monitoring. Only after completing these steps — including monitored conditions afterward — may participants rejoin the general prison population (TDCJ, 2023). One successful graduate of GRAD, a former Tango Blast member, now mentors’ other inmates to leave gangs.

Despite these efforts, STGs continue to challenge correctional systems with encrypted communication, external networks, and the potential for violence against informants or defectors. This means controlling prison gangs requires not just correctional interventions but also broader community-based gang prevention programs, partnerships with law enforcement, and intelligence-sharing across agencies.

Gender Differences in Prison Gangs

Prison gangs are overwhelmingly a male phenomenon. Gang membership often requires committing a violent act — such as assault or murder — against another inmate to gain entry. While women in prisons do sometimes engage in violence, their involvement in formal prison gangs is minimal. Instead, women more commonly form pseudofamilies, informal family-like groups with roles such as “mother,” “father,” “daughter,” or other relatives. These pseudofamilies serve social and emotional needs rather than engaging in organized violence (Kristine & Chambliss, 2011).

Demographics and the Broader Context

The gang landscape in prisons reflects the broader correctional population, which is overwhelmingly young, poorly educated, unemployed or underemployed, and disproportionately Black or Hispanic. In 1992, Black individuals made up 47% of state prison admissions, compared to 19% for Hispanics (Perks, 1994). According to the U.S. Sentencing Commission (2024), half of those sentenced in fiscal year 2024 were Hispanic, 25% were Black, and 21% were White. The Prison Policy Initiative (2024) confirms that people of color continue to be overrepresented in both carceral and non-carceral punishments.

Conclusion

In conclusion, prison gangs are almost exclusively a male phenomenon. They are violent and pose a persistent and complex problem concerning the security of prison/jail institutions as well as a threat to public safety. For an inmate to belong to a prison gang, violence is often required for membership, with many gangs requiring a violent act such as murder or assault to be performed against another inmate to gain admission. Female prisons or jail rarely have gangs. Kristine and Chambliss (2011), maintain that while there are some female inmates, the violence engaged in are not due to gang membership. More common in female prisons are the formation of pseudofamilies rather than gangs.

Discussion Questions

- Why has it been difficult to define prison gangs?

- Why are prison gangs referred to as security threat groups (STGs) in correctional settings?

- How do prison gangs differ structurally from street gangs?

3.5: Types of Offenders in the Corrections

Classification not only determines custody levels but also helps define the types of offenders within corrections. Understanding these categories is essential for tailoring treatment, supervision, and rehabilitation (Clear, Reisig, & Cole, 2021).

Table 3.5.1 – Types of Offenders in Corrections

| Type of Offender | Definition | Key Characteristics | Correctional Considerations |

| Situational Offenders | Commit crimes under unusual circumstances, often first-time | Rarely reoffend, low risk | Often diverted to probation or community sanctions |

| Organized Crime Offenders | Members of sophisticated groups with profit motives | Structured, hierarchical, transnational networks | Require intensive law enforcement tools (e.g., RICO) |

| Habitual Offenders | Repeat offenders with prior convictions | Cycle through system, linked to poverty, substance abuse | Harsh penalties in some states; often confused with “career” criminals |

| Career Criminals | Chronic offenders with early onset and long criminal histories | High recidivism; often violent or drug-related | Require strict sentencing and intensive supervision |

| Professional Offenders | Skilled criminals who treat crime as full-time work | Specialized knowledge and techniques | Hard to apprehend; operate in organized networks |

| White-Collar Offenders | Nonviolent, financially motivated crimes (fraud, embezzlement) | Higher social status, deceptive practices | Sentences vary; social/economic harm is high |

| Public Order Offenders | Crimes disrupting social norms (e.g., prostitution, intoxication) | Often nonviolent, low risk | Diversion to treatment or community programs |

| Long-Term Offenders | Sentenced to 20+ years or life | Can be young, aging, or lifers | Risk of institutionalization; require long-term planning |

| Death Row Offenders | Sentenced to execution for capital crimes | Predominantly male, racially disproportionate | Held in isolation; declining mental health common |

Source: Adapted from Clear, Reisig, & Cole (2021).

Situational Offenders

First-time offenders who act under stress or provocation. Typically, low-risk, they often benefit from probation, counseling, or diversion programs (Clear et al., 2021). Haskell and Yablonsky (1974) described these situational offenders in their book, Crime and Criminality, as a person acting out of temporary stress, provocation, or extreme emotion, and are unlikely to reoffend. For example, someone who commits manslaughter during a sudden fight but has no prior record could be considered a situational offender.

Organized Crime Offenders

Operate in structured, transnational groups such as cartels or smuggling networks, generating billions annually (UNODC, 2009). These groups can operate nationally or transnationally and may engage in a variety of crimes like drug trafficking, human smuggling, money laundering, cybercrime, or extortion (The Mob Museum, 2025). More sophisticated than prison gangs, they require specialized tools like the RICO Act to dismantle.

Habitual and Career Criminals

Habitual offenders cycle through the system, often tied to substance use or poverty. The criteria for labeling someone a habitual offender differ by jurisdiction. “Three Strikes” laws have targeted them, sometimes excessively for nonviolent crimes.

Career criminals represent the most persistent group, with early onset and lifelong offending. They commit a disproportionate share of serious crimes, making them the focus of strict sentencing and intensive supervision (USSC, 2023). According to the U.S. Sentencing Commission (2023), federal career offenders must have at least two prior felony convictions and commit another qualifying serious offense to trigger enhanced sentencing.

Professional Offenders

Professional criminals, described by Edwin Sutherland in The Professional Thief, see crime as a skilled occupation. They specialize in fraud, burglary, or cybercrime and often belong to larger networks (Bouchard, Martin. (2020).

White-Collar Offenders

Coined by Sutherland (1940), these offenders commit financially motivated crimes such as fraud or embezzlement. Though nonviolent, their crimes can devastate communities and erode trust. Sentences often appear lenient compared to their social harm.

Public Order Offenders

Sometimes called “victimless crimes,” these include prostitution, drug use, or public intoxication. They disproportionately affect disadvantaged groups. Many jurisdictions now favor diversion programs like Seattle’s LEAD, which connect offenders to treatment and housing rather than jail.

Long-Term Offenders

Offenders who are serving 20 years or more for serious crimes. They may be young, aging lifers, or career criminals. Over time, many adjust to prison culture, sometimes becoming “model inmates” (Flanagan, 1991).

Table 3.5.2 – Long-Term Offenders in Six Largest U.S. Prison Systems

| State/System | No. of Inmates | % Serving 20+ Years | Date Recorded |

| California | 102,412 | 16.6% | 1992 |

| Florida | 46,233 | 21.7% | 1991 |

| Michigan | 33,688 | 15.5% | 1991 |

| New York | 58,933 | 6.8% | 1992 |

| Texas | 50,172 | 52.9% | 1992 |

| Federal Bureau of Prisons | 66,328 | 14.9% | 1992 |

Source: Maghan (1996)

Long-term confinement brings challenges such as depression, anxiety, and “prisonization.” Research shows stress is highest in the first few years, often declining as inmates adapt (MacKenzie & Goodstein, 1985).

Death Row Offenders

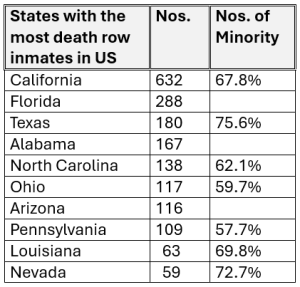

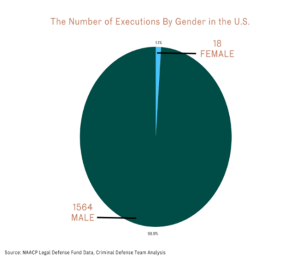

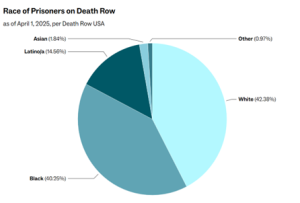

As of 2025, about 2,100 individuals were on death row, mostly men. Numbers have declined for 20 years.

- States with the largest death row populations: California, Florida, Texas, Alabama.

- Minorities are overrepresented, with Black defendants far more likely to receive death sentences when victims are White (Pierce & Radelet, 2011).

The Death Penalty Information show that that national death row population has declined for 20 consecutive years. Figure 3.5.2 below show the number of prisoners under sentence of death, 1953–2022.

Race and Death Row

In terms of who these offenders are, the NAACP Legal Defense & Educational Fund (2025, 2024) and the Death Penalty Information Center (2024) reports that they comprised of males, people of color, as previously mentioned, and individuals with limited education and socioeconomic backgrounds. Racial and ethnic minorities, especially Black individuals, are overrepresented compared to their proportion of the general population. As shown in the figure 3.4.8.3 by the Death Penalty Information Center, show racial and ethnic minorities, especially Black individuals, are overrepresented by 41 percent compared to their proportion of the general population, which has been the case for and long time and continues to be (Prison Policy Initiative, 2025).

Other Characteristics:

Most death row inmates have limited education (half did not complete high school) and lower-than-average IQ scores (Cunningham et al., 2011). Many also face trauma, mental illness, or disabilities.

Held in extreme isolation, they spend up to 23 hours per day in cells, often suffering psychological deterioration. Older inmates face additional health challenges. Scholars argue these conditions amount to cruel and unusual punishment (ACLU, 2013).

Conclusion

Offender typologies reveal the complexity of correctional populations. From situational and public-order offenders to lifers and death row inmates, each group presents distinct risks and needs. Correctional systems must respond with targeted strategies that ensure safety, uphold justice, and promote rehabilitation where possible.

3.6: Offenders with Special Needs in the Corrections

“Tough on crime” policies (mandatory minimums, three-strikes, truth-in-sentencing, reduced parole) have increased the number of people with special needs in custody. Corrections must now manage juveniles, sex offenders, people with substance use and mental illnesses, individuals with disabilities, elderly prisoners, pregnant women, LGBTQ+ people, veterans, and immigrants—each requiring tailored policies, housing, treatment, and reentry planning.

Table 3.6.1 – Offenders with Special Needs in the Corrections

| Type of Offender | Definition | Key Characteristics | Correctional Considerations |

| Juvenile Offenders | Children in conflict with the law | Often first-time, developmentally distinct | Community-based sanctions; developmentally appropriate services |

| Chronic Juvenile Offenders | Youth with persistent reoffending | Frequent/early onset | Close supervision; structured, family-involved interventions |

| Serious Juvenile Offenders | Youth committing grave violent crimes | High harm; sometimes without prior record | Possible adult transfer; intensive supervision & treatment |

| Sex Offenders (Adult & Juvenile) | Convicted of sexual crimes | Stigma, victimization risk | Specialized assessment/treatment; registry & strict supervision |

| Substance-Abusing Offenders (Adult & Juvenile) | Alcohol/drug dependence co-occurs with crime | High relapse/recidivism risk | Drug courts; CBT/MST; treatment + monitoring |

| Mentally Ill Offenders (Adult & Juvenile) | Diagnosed mental disorders | Compliance, safety, care gaps | Psychiatric services; protective housing; continuity of care |

| Developmentally Disabled Offenders | Intellectual/developmental disabilities | Vulnerability; comprehension limits | Simplified communication; advocates; safe placement |

| Elderly Offenders | 50/55+ with geriatric needs | Chronic illness, mobility limits | Medical care; accessibility; geriatric units/compassionate release |

| LGBTQ+ Offenders (Adult & Juvenile) | Diverse sexual orientations/gender identities | Heightened victimization risk | Anti-victimization policies; gender-affirming care; safe housing |

| Pregnant/Motherhood Offenders | Pregnant/incarcerated women & new mothers | High medical/social needs | Prenatal care; anti-shackling; nursery/alternatives to custody |

| Veteran Offenders | Incarcerated former service members | PTSD/TBI; homelessness risk | Trauma-informed care; veteran courts; VA benefits linkage |

| Immigrant Offenders | Non-citizens in the system | Language/legal barriers | Due-process safeguards; cultural competence; agency coordination |

Source: Adapted from Gideon (2013) with updates from cited studies.

Juvenile Offenders

The juvenile system emphasizes rehabilitation, but serious or chronic cases may be waived to adult court (judicial waiver, statutory exclusion, direct file). Youth in adult facilities face greater suicide risk and victimization; racial disparities persist (Black, Native, and Latino youth are overrepresented). Use developmentally appropriate programming, family engagement, and diversion whenever feasible, reserve adult transfer for the most serious cases.

Sex Offenders (Adults and Juveniles)

Sex offenses range from rape to child exploitation; there is no single profile. Individuals carry low status in prison and face elevated victimization. Effective responses include specialized assessment, CBT-based treatment, careful housing, and reentry planning that addresses registry obligations and community safety. Research on female sex offenders remains limited and should expand.

Substance-Abusing Offenders

Substance use disorders are widespread among people in custody; many arrests test positive for drugs and reoffending is often addiction-driven. Evidence shows treatment-oriented approaches (drug courts, medication-assisted treatment, therapeutic communities, CBT, family-based models for youth) outperform punishment-only responses. Supervision should include relapse-responsive conditions, not just sanctions.

Mentally Ill Offenders

Jails and prisons have become de facto mental health institutions. Around two in five incarcerated people report a mental illness, with service gaps common. Priorities: standardized screening at intake, timely access to psychiatric care, suicide prevention, crisis stabilization, discharge planning, and community care linkage. Women often face compounding stressors and fewer program opportunities, elevating mental-health needs.

Disabled Offenders

People with disabilities (psychiatric and non-psychiatric) are overrepresented. Common needs include cognitive support, mobility aids, and accessible formats. Risks include inappropriate disciplinary segregation for behavior linked to disability, which increases self-harm. Best practices: reasonable accommodation, accessible housing/programs, trained staff, and alternatives to isolation.

Elderly (Geriatric) Offenders

An aging prison population requires chronic-care management, mobility aids, dementia-informed practices, and hospice (e.g., Angola’s program). Typologies (first-incarcerated, long-termers, multiple-incarcerated) differ in risks and adjustments. Many older adults pose low public-safety risk; consider geriatric units and compassionate release when appropriate (Aday, 1983, 2002, 2003).

Pregnant and Motherhood Offenders

Essential policies include prenatal care, anti-shackling during transport/labor, and humane postpartum practices. Separation from newborns harms attachment; some systems use nursery programs or alternatives to incarceration for eligible cases. Early, routine prenatal care improves outcomes; late/insufficient care correlates with adverse events. Align practice with medical standards and civil-rights rulings.

LGBTQ+ Offenders

LGBTQ+ people—especially transgender individuals—are overrepresented in the system and face heightened risks of sexual/physical victimization. Needs include safe housing, gender-affirming healthcare (e.g., hormones), and protection from discriminatory practices (including inappropriate “protective” solitary confinement). Youth in this group are heavily overrepresented in juvenile systems; use non-carceral and protective responses where possible.

Veteran Offenders

Some veterans struggle with PTSD, TBI, substance use, homelessness, and re-entry to civilian life, elevating justice-involvement risk. Responses: veteran treatment courts, trauma-informed programming, peer mentorship, and VA benefits coordination. Offense patterns vary; supervision should integrate clinical care and housing/employment supports. Orak’s research contribution to literature is certainly a good place to start understanding the issues of the incarcerated veterans.

Immigrant Offenders

Most immigrant offenses relate to status violations; decades of research show immigrants are less crime-prone than the native-born. In custody, prioritize language access, cultural competence, due-process protection, and coordination with immigration authorities. Avoid blanket assumptions, tailor services to legal status, family ties, and reentry risks.

Discussion Questions

- Discuss the difference between the mentally ill offender and the offender merely having mental health issues.

- Why have special-needs offender populations increased in correctional institutions over recent decades?

3.7: The State of Louisiana: The handling of its’ Offender Population – Incarcerated and non-incarcerated offenders

Overview

Louisiana’s correctional system has long been shaped by its colonial past, racial disparities, and reliance on incarceration. So, to understand “corrections” in the state, it is important to look at a few things, such as 1) the state original French and Spanish governorship, 2) the Louisiana’s correctional ideologies, then and now, 3) the heavy reliance on incarceration, and 4) the Louisiana’s long history of racial disparities and inequalities in the entire criminal justice system, and the corrections segment particularly. Louisiana was under French rule from 1682 to 1762, then briefly again from 1801 to 1803 before the Louisiana Purchase. In short, to avoid the complexity of when France ruled and Span ruled, the Spanish governorship began with its first governor in 1766, eventually establishing Spanish colonial institutions after suppressing a French revolt in 1768. Early French and Spanish codes emphasized harsh punishments, including branding, maiming, and executions, particularly for Black offenders under the Code Noir under France and Span establishing a civil law framework, known as Las Siete Partidas. Las Siete Partidas that established a codified, or statutory, legal tradition that endures in Louisiana differentiating it from the common law system used by all other U.S. state (Rabalais, 1982). Both these Franch and Spanish practices created a legacy of unequal treatment that continues to influence Louisiana corrections to this date.

Louisiana’s correctional ideologies historically leaned toward incapacitation (“warehousing”) and retribution (“payback”), focusing on removing offenders from society rather than rehabilitation. While the Department of Public Safety and Corrections (DPS&C) now emphasizes safety, supervision, and opportunities for change, in practice, Louisiana still relies heavily on incarceration.

It should not come as no surprise to the average reader that Louisiana’s criminal justice system has deep historical ties to slavery, particularly when examining the practices implemented in the State’s prison system. The States’ largest maximum-security prison, Louisiana State Penitentiary-LSP, also known as Angola, was initially referred to as a planation prison because it originated from a plantation system that predated and continued after the Civil War. LSP is still located on that same land that was formerly the Angola Plantations, a large slave plantation owned by a slave trader before the Civil War. This historical legacy of forced labor on the same planation land is the reason for the prison’s nicknames such as “Alcatraz of the South”, “The Farm”, and “The Bloodiest Prison in America” (Louisiana Prison Museum & Cultural Center Website).

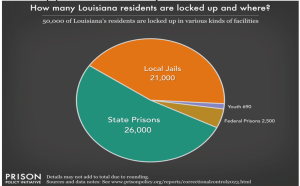

The state has one of the highest incarceration rates in the world—1,067 per 100,000 people (Prison Policy Initiative, 2023), currently second to the State of Mississippi. Most incarcerated individuals are poor, undereducated, and disproportionately Black, reflecting deep racial disparities in arrest and sentencing patterns.

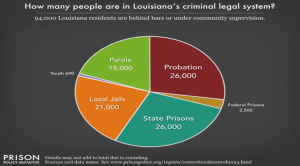

Louisiana Adult Corrections and Partnership with Sheriffs and Jails

A unique feature of Louisiana corrections is its dependence on local parish jails to house state prisoners. The jail partnership was a response to overcrowding that had reached a crisis point in the 1970s and 80s. One of the factor that forced, such move was a1975 lawsuit filed by inmates at the Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola led a federal judge to declare the prison in an “extreme public emergency” due to overcrowding and other issues. Since the 1990s, the state has contracted sheriffs to keep thousands of state inmates in jails rather than prisons. In 2023, more than 21,000 state prisoners were held in local jails (Figure 3.7.1). In this type of arrangements there are benefits and drawbacks, such as:

- Benefits: cost savings, use of existing facilities, and reduced prison overcrowding.

- Drawbacks: jails are designed for short-term detention, so inmates have fewer programs, limited healthcare, and weaker reentry support. Studies also show higher suicide and overdose rates compared to prisons.

Under this partnership, the Louisiana Department of Public Safety and Corrections (DPSC) pay local sheriffs a per diem rate to house thousands of state inmates in their parish facilities. This arrangement, originally intended as a temporary fix, created a lasting financial and structural dynamic for Louisiana’s correctional system. While the prison/jail partnership is great for state policy makers, correctional administrators, political leaders, it may not be great for prisoners. Andrea Armstrong, a co-author of a 2022 report on the state’s criminal justice system, maintains that prisoners in jails often have less access to education and treatment for chronic health conditions than their counterparts in state prisons.

Who Are the Offenders?

Most inmates in Louisiana jails and prisons are serving time for violent crimes, though many are also incarcerated for drug, property, or parole violations. Vulnerable populations such as juveniles charged as adults, the elderly, and the mentally ill are also present. Race is a critical factor. In 2023, 65% of Louisiana inmates were Black, despite Black people making up only one-third of the state’s population. In some parishes, Black residents accounted for up to 89% of the jail population. Cities like Bogalusa, Ville Platte, and Bastrop have imprisonment rates even higher than New Orleans or Baton Rouge (Table 3.7.1).

Table 3.7.1 – Louisiana Cities with Heavy Black Populations and High Incarceration (2023)

| Name of Cities | Black Population Numbers | Prison Numbers | Percentage (%) |

| New Orleans | 206,000 (55.22) | 2,519 | 1.22 |

| Shreveport | 103,000 (56.00) | Not Available | — |

| Baton Rouge | 114,000 (53.00) | Not Available | — |

| Bogalusa | 4,960 (47.00) | 180 (in prison) | 1.69 |

| Ville Platte | 4,190 (66.69) | 80 (in prison) | 1.91 |

| Bastrop | 7,450 (79.2) | 180 (in prison) | 2.42 |

| Marksville | 2,000 (40.23) | Not Available | — |

The two graphs below illustrate the proportion of offenders housed in local jails and prisons in 2023 as well as the racial and ethnic breakdown of offenders in the years 2021 and 2019. See Figure 3.7.1 and Figure 3.7.2.

No matter what the chart shows or the study reports, race is a significant factor contributing to disparities within Louisiana’s criminal justice system. A pattern that has existed for a long time. The arrest rates are higher of Blacks, both men and women, particularly among young men, the sentencing rates are higher as well as the incarceration rates. As the State of Louisiana grapples with the high cost of incarceration, recidivism, the upticks with crime (i.e., violent, drugs, etc..), the prevalence of the special needs offender populations, the state has failed to address the racial inequalities the plagues its criminal justice system.

As shown in the figure above, these percentages illustrate stark disparity and racial inequality within the state’s incarceration practices. Smith and Sarma (2012) wrote in a Louisiana Law Review article that Louisiana “laws enacted by nineteenth-century white supremacists continues to operate today and do so —regardless of modern intent—in a way that executes their intended discriminatory purposes” (p. 363).

When examining the entire Louisiana Criminal Justice System, the sentencing and incarceration or non-incarceration in the year 2022, the Prison Policy Initiative shows the breakdown to be approximately 44,000 persons in community corrections and another 47,000 in correctional institutions, as noted in Figure 3.7.4 below. More specifically 18,000 on parole, 26,000 on probation and as shown earlier 21,000 in local jails and 26,000 in prisons. While incarceration rates are still high, since 2018, Louisiana has dropped to the second highest state in incarceration. The State of Oklahoma surpassed Louisiana in 2018 and since 2019, Mississippi has held the highest incarceration rate in the United States, according to the U.S. News & World Report and the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS).

Juvenile Offenders in Louisiana

Louisiana’s juvenile justice system began in 1906 with the passage of Act No. 82. This was during a period that reflects the state’s segregated history. White youth were sent to reformatories school, later called training institutes, while Black male youth were often sent to Angola Prison, a maximum-security adult facility. Similar options were given to Black girls. Regardless of age of Black girls, they were sentenced to hard labor and sent to the female quarters of the Louisiana State Penitentiary. It was not until 1948 that a facility for Black youth was established, as segregation continued to persist until 1969.

The juvenile court jurisdiction in Louisiana, like other states, the age of the offender is one factor used by each state legislature to determine the minimum and maximum age at which a person is considered a juvenile or an adult. The most common maximum age of a juvenile court jurisdiction is 17, meaning that in states that classify 17 as the maximum age of juvenile court jurisdiction. A 17-year-old who commits an offense should be processed in juvenile court. The offense or criminal act was another major factor considered.

The age and serious nature of crime were not the only factors weighing in on the decision of how juveniles are defined by law even after the establishment if the first Juvenile court in America. It took years before things would change for certain youths of color. For instance, in the State of Louisiana Juveniles handled by the Corrections segment of the juvenile and/or criminal justice systems has a history of handling youths differently based on race from the inception of the State’s juvenile Justice/court System.

While the America juvenile justice system can be traced to Cook County, Chicago, Illinois, in 1899, the State of Louisiana started its juvenile justice system much later. The Cook County juvenile justice system in the United States was originally founded on the doctrine of parens patriae, dogma that promotes creating a separate system aimed at therapy, rehabilitation, and addressing the underlying causes of youth misbehavior to redirect young lives.

In Louisiana, the establishment of juvenile justice facilities reflected the broader segregated system of government. Implementing a juvenile justice system also proved to be problematic at first. For instance, the Louisiana State Legislature first attempted to establish a statewide juvenile court system with Act No. 82 of 1906, but this was declared unconstitutional. A significant step was then made in 1908 when Act No. 83 was passed, creating a Juvenile Court specifically for the Parish of Orleans, and this became a part of the 1898 Constitution. Later, the 1913 Constitution, enacted in 1913, broadened the scope to include provisions for Juvenile Courts in all Louisiana parishes. It was not until 1904 that the General Assembly passed Senate Bill No. 51, creating Act No. 82 which amended the Louisiana Constitution of 1898. The legislature in 1906 authorized a reformatory school in Monroe exclusively for white boys, later renamed the Louisiana Training Institute. In 1926, a State Industrial School for white girls was created, and by the 1940s, similar facilities operated for white youth across the state (Budd, 2024; The Law Library of Louisiana, n.d.).

The U. S. Supreme Court’s ruled in Brown v. Board of Education (1954) that segregation in public education was unconstitutional, overturning Plessy v. Ferguson (1896). The State of Louisiana, however, continued to operate racially segregated correctional institutions well into the 20th century. So, Black youth did not receive the protection of the juvenile court until much later.

Black youth faced particularly harsh treatment in the name of justice. In 1928, with the advocacy of J.D. Lafarque and Southern University President J.S. Clark, the legislature was persuaded to establish a facility for African American youth. Still, it was not until 1948 that the State Industrial School for Colored Youth opened in Scotlandville, housing both boys and girls until 1956, when a separate dormitory for girls was built. Full desegregation of Louisiana’s juvenile facilities did not occur until a 1969 Louisiana Supreme Court order. Prior to that, many Black boys were not sent to juvenile training schools at all but instead to Angola—the Louisiana State Penitentiary—where they were treated as adult convicts and subjected to hard labor (Adams, n.d.; Gilmore, 2006; Whitney, 2010).

Before leaving this discussion, it is important to mention that children in need of supervision (i.e., also called status offenders). The State of Louisiana’ juvenile justice system began addressing status offenses, which are acts that are only illegal because of the offender’s age, in the early 1970s. Prior to that time the status offenders were handled similarly to delinquent offenders (those who commit crimes). That did not change until 1974 with the passage of the Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act (JJDP Act). One of the things the Act did was prompted a national movement to differentiate between status offenders and delinquent offenders. The JJDP Act encouraged states to deinstitutionalize status offenders, meaning they should not be placed in secure detention or correctional facilities.

Today, Louisiana law allows juveniles as young as 14 to be prosecuted as adults for serious crimes. While the system was originally designed to “save children” through rehabilitation, racial disparities persist. Black youth are still disproportionately transferred to adult courts and face harsher outcomes.

Louisiana’s reliance on Angola Prison for youth has been widely criticized. In the mid-2000s, the state housed more than 300 juveniles in adult prisons, second only to Pennsylvania. Most were sentenced for serious violent crimes.

The Miller v. Alabama (2012) decision ruled that mandatory life without parole for juveniles was unconstitutional, reducing the number of youth lifers. Yet as of 2022, 70–80 children—almost all Black boys—remained at Angola (ACLU, 2023).

Conclusion

Louisiana’s correctional system is deeply rooted in a history of punitive ideologies, racial inequality, and heavy reliance on incarceration. From colonial codes and slavery through convict leasing and present-day partnerships with local jails, the state has consistently prioritized retribution and incapacitation over rehabilitation. This has resulted in the highest incarceration rates in the nation, persistent racial disparities, and continued challenges in the treatment of vulnerable populations, including juveniles. While reforms have been introduced, meaningful change requires a commitment to equity, rehabilitation, and reintegration in order to break from /the state’s legacy of mass incarceration and systemic injustice. So, the key features of Louisiana Corrections can best be described as:

- Overreliance on jails, detention, and prisons → overcrowding and high costs.

- Highest incarceration rate in the U.S. and among the highest globally.

- Dominant ideologies: incapacitation and retribution.

- A life sentence means life without parole.

- Louisiana remains a death penalty state (lethal injection).

References

Aday, R. (2003). Aging prisoners: Crisis in American corrections. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger Publishers.

Aday, R. H. (2002). Aging prisoners: Crisis in American corrections. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger Publication.

American Civil Liberties Union-ACLU (2013, July). A death before dying: Solitary confinement on death row. https://assets.aclu.org/live/uploads/publications/deathbeforedying-report.pdf

Armstong, A. & Kondkar, M. (2022, October). Louisiana justice: Pre-trial, incarceration, & reentry, public welfare Foundation.

Armstong, A. & Kondkar, M. (2022, October). Opportunities for philanthropy in Louisiana’s Justice System, Public Welfare Foundation.

Baird, S. C., Sturrs, G. M., & Connelly, H. (1984). Classification of juveniles in corrections: A Modern system approach, NCJRS: Department of Justice. https://www.ojp.gov/ncjrs/virtual-library/abstracts/classification-juveniles-corrections-model-systems-approach

Beck, C, F. (1990). Drug enforcement and treatment in prison. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Justice.

Beck, A. J., Berzofsky, M., Caspar, R., & Krebs, C. (2014). Sexual Victimization in Prisons and Jails Reported by Inmates, 2011–12 update. Bureau of Justice Statistics.

Black’s Law Dictionary. (2024, June). 12th Edition. Thomson Reuters Publisher.

Bouchard, Martin. (2020). A network perspective on collaboration and boundaries in organized crime. In Organizing Crime: Mafias, Markets, and Networks, edited by Michael Tonry and Peter Reuter. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Budd, K. M. (2024, July). Incarcerated women and girls. The Sentencing Project. https://www.sentencingproject.org/fact-sheet/incarcerated-women-and-girls/

Bureau of Prisons website (2025 as of February 12,)

Clear, T. R., Reisig, M. D., & Cole, G. F. (2021). American Corrections (13th ed.). Cengage Learning.

Covington, S. S., & Bloom, B. E. (2007). Gender responsive treatment and services in correctional settings. Women & Therapy, 29(3-4), 9–33. https://doi.org/10.1300/J015v29n03_02

Covington, S. (2007). The relational theory of women’s psychological development: Implications for the criminal justice system. In Zaplin, R. (Ed.), Female offenders: Critical perspectives and effective interventions.

Cunningham, M. D., Sorensen, J. R., Vigen, M. P. & Woods, S. O. (2011). Inmate homicides: Killers, victims, motives, and circumstances. Journal of Criminal Justice, 38 (4), 348-358.

Death Penalty Information Center (2024, June). The Death Penalty in 2024 Report. https://dpic-cdn.org/production/documents/DPI-2024-Year-End-Report.pdf?dm=1735847939

Doucet, G. & Adu-Frimpong, A. (2025). Reimagining justice: The power of community-based corrections. New York: Barnes & Noble.

Estelle v. Gamble, 429 US. 97 (1976). Supreme Court decision. https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/429/97/

Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). (n.d.). What we investigate: Gangs. https://www.fbi.gov/investigate/violent-crime/gangs

Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). (n.d.). Transnational organized crime. https://www.fbi.gov/investigate/transnational-organized-crime

Flanagan, T. (1991). Sentence planning for long-term inmates. Federal Probation, 23-28.

Gideon, L. (2013). Special needs offenders in correctional institutions. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publisher.

Hardyman, P. L., Austin, J., & Peyton, J. (2004). Prisoner intake systems: Assessing needs and classifying inmates. U.S. Department of Justice, National Institute of Corrections.

Haskell, M. R. & Yablonsky, L. (1974), Crime and Criminality. Rand McNally College Pub. Co.inmaesAID. (2025). Addressing Mental Health and Substance Abuse in Correctional Facilities. nmaesAID. Addressing Mental Health and Substance Abuse in Correctional Facilities

Haskell, M.R. & Lewis Yablonsky, L. (1974). Crime and criminality a situational. Criminology .

James, D. J., & Glaze, L. E. (2006). Mental Health Problems of Prison and Jail Inmates. Bureau of Justice Statistics. Congressional Research Service,

Kristine, M.L. & Chambliss, W. J. (2011). Gang and violence in prison, Chapter 4 on Corrections, Sage Publication Inc.

Latessa, E. J., & Smith, P. (2011). Corrections in the Community (5th ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315721965

Louisiana. Louisiana Prison Museum & Cultural Center Website, https://www.angolamuseum.org/historyof-angola#

Maruschak, L. M., Berzofsky, M., & Unangst, J. (2015). Medical Problems of State and Federal Prisoners and Jail Inmates, 2011–12. Bureau of Justice Statistics.

Maruschak, L. M., Bronson, J., & Alper, M. (2021). Parents in prison and their minor children: Survey of prison inmates, 2016. Bureau of Justice Statistics. https://bjs.ojp.gov/library/publications/parents-prison-and-their-minor-childrensurvey-prison-inmates-2016

Maschi, T., Viola, D., & Koskinen, L. (2015). Trauma, stress, and coping among older adults in prison: towards a human rights and intergenerational family justice action agenda. Traumatology, 21(3), 188–200. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/trm0000021

National Gang Center (n.d.) About gangs. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice. https://nationalgangcenter.ojp.gov/

Mears, D. P. (2010). American Criminal Justice Policy: An Evaluation Approach to Increasing Accountability and Effectiveness. Cambridge University Press.

Meyer, I. H. (2015). Resilience in the study of minority stress and health of sexual and gender minorities. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 2(3), 209–213. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000132

Mistrett, M. & Espinoza, M. (2021, December). Youth in adult courts, jails, and prisons. The Sentencing Project. https://www.sentencingproject.org/reports/youth-in-adult-courts-jails-and-prisons/

National Conference of State Legislatures. (2022). Racial and ethnic disparities in the criminal justice system. https://www.ncsl.org/civil-and-criminal-justice/racial-and-ethnic-disparities-in-the-criminal-justicesystem#:~:text=An%20)ctober%20from%The%20Sentencing,rate%

Prison Policy Initiative’s Reports presented by Sawyer, W. & Wagner, P. (2025, March). Mass Incarceration: The whole pie 2025. https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2025.html

Prison Policy Initiative’s Reports presented by Sawyer, W. & Wagner, P. (2023, March). Mass Incarceration: The whole pie 2023. https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2025.html

Rabalais, R. J. (1982). The influence of Spanish laws and treatises on the jurisprudence of Louisiana: 1762-1828. Louisiana Law Review, 42(5), 1485-1508.

Rovner, J. (2024, August). Youth justice by the numbers. The Sentencing Project. https://www.sentencingproject.org/policy-brief/youth-justice-by-the-numbers/

Shelden, R. (2012, July). Slavery’s legacy alive and well in Louisiana. Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice. https://www.cjcj.org/news/blog/slaverys-legacy-alive-and-well-in-louisiana#:~:text=Douglas%20Blackmon%27s%20best%2Dselling%20book,and%20then%20to%20local%20businesses.

Sinclair, N. (2023). Gang Involvement. Gang Involvement | EBSCO Research Starters

Smith, R. J. & Sarma, B. J. (2012). How and why race continues to influence the administration of criminal justice in Louisiana, Louisiana Law Review, 72(2), 361-407.

Snarr, R. W. & Wolford, B. I. (1985). Corrections. Dubuque, Iowa: Wm. C. Brown Publishers.

Taxman, F. S., Cropsey, K. L., Young, D. W., & Wexler, H. (2007). Screening, assessment, and referral practices in adult correctional settings: A national perspective. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 34(9), 1216–1234. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854807304431

Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ). (2023). Security Threat Groups. Security Threat Group Management Office FAQ Pamphlet. https://www.tdcj.texas.gov/documents/cid/STGMO_FAQ_Pamphlet_English.pdf

Texas Department of Public Safety. (2017). DPS Releases Texas Gang Threat Assessment. https://www.dps.texas.gov/section/intelligence-counterterrorism-division/texas-gang-threat-assessment

The Mob Museum (2025). Organized crime today. https://themobmuseum.org/exhibits/organized-crime-today/

The Death Penalty Information Center Website— a national, non-profit organization dedicated to providing data, analysis, and news about the death penalty. https://deathpenaltyinfo.org/

U.S. Sentencing Commission, (n.d.). Career offenders- FY 2020 through FY 2024. https://www.ussc.gov/research/quick-facts/career-offenders#:~:text=A%20career%20offender%20is%20someone,felony%20convictions%20for%20those%20crimes. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-9133.12097

Tsai, J., Mares, A., & Rosenheck, R. A. (2012). Does housing chronically homeless adults lead to social integration? Psychiatric Services, 63(5):427-34. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.201100047.

Underwood, L.A. & Washington, A, (2016, February). Mental illness and juvenile offenders. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 13(2), 1-14. doi: 10.3390/ijerph13020228

Van Voorhis, P., Wright, E. M., Salisbury, E., & Bauman, A. (2010). Women’s risk factors and their contributions to existing risk/needs assessment: The current status of a gender-responsive supplement. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 37(3), 261-288. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854809357442

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crimes. (2020, April). Defining organized crime. https://www.unodc.org/e4j/ru/organized-crime/module-1/key-issues/defining-organized-crime.html

Venture, A. (2019). Incarceration trend in Louisiana. VERA Institute of Justice. https://verainstitute.files.svdcdn.com/production/downloads/pdfdownloads/stateincarceration-trends-louisiana.pdf

VERA Institute of Justice (n.d.). Incarceration trends in Louisiana. https://vera-institute.files.svdcdn.com/production/downloads/pdfdownloads/state-incarceration-trends-louisiana.pdf

World Prison Brief (2025, February). Female prison population growing faster than male, worldwide. https://www.prisonstudies.org/news/female-prison-population-growing-faster-male-worldwide#:~:text=Since%202000%

Zhen Zeng, Z. (2023, June). Juveniles incarcerated in U.S. adult jails and prisons, 2002–2021. NCJ 306140. BJS Statisticians. https://bjs.ojp.gov/juveniles-incarcerated-us-adult-jails-and-prisons-2002-2021

Media Attributions

- FIG 3.2.1 © Federal Bureau of Prison, reported on 7 June 2025

- FIG 3.2.2 © Federal Bureau of Prison, reported on 7 June 2025

- FIG 3.5.1A © NAACP Legal Defense & Educational Fund, Death Row USA, Summer 2024

- FIG 3.5.1B © NAACP Legal Defense & Educational Fund, Death Row USA, Summer 2024

- FIG 3.5.2 © Bureau of Justice Statistics, National Prisoner Statistics program (NPS-8), 1953–2022, by Tracy L. Snell, BJS Statistician.

- FIG 3.5.3 © Death Penalty Information Center

- FIG 3.6.1 © Orak, U. (2023, October). From service to sentencing: Unraveling risk factors for criminal justice involvement among U.S. veterans. Council on Criminal Justice.

- FIG 3.7.1 © Wendy Sawyer, September 2023. Prison Policy Initiatives

- FIG 3.7.2 © Wendy Sawyer, September 2023. Prison Policy Initiatives

- FIG 3.7.3 © Wendy Sawyer, September 2023. Prison Policy Initiatives

- FIG 3.7.4 © Leah Wang, May 2023. Prison Policy Initiatives