Chapter 4 – Alternatives to Incarceration

Joel George

Learning Objectives

- Discuss the history and development of probation and parole

- Describe types of sanctions and alternatives to incarceration

- Explain how community service works and the functions of restorative justice

- Assess specialty courts and treatments

- Evaluate types of fines and restitution as a form of punishment

Introduction

Historically, offenders primarily faced prison sentences. However, due to John Augustus’s initiatives in the 19th century and advancements in the 1960s, community corrections gained traction. Probation and parole became standard practices within the correctional system. These measures enable convicted individuals to maintain some structure and meet control requirements during their rehabilitation in the community. The chapter also addresses the Interstate Act of 1937 and highlights the essential role of the probation officer, who has significant responsibilities in facilitating the successful reintegration of offenders into society.

4.1 Historical developments of probation

Probation is very similar to Parole, and many legal issues are identical. Numerous jurisdictions combine the roles of probation and parole officers, and these officers are often employed in community corrections departments.

Probation, possibly the most traditional and widely used of intermediate sanctions, traces its origins to common law principles from England, similar to several other correctional methods employed in the United States. In the early American judicial system, individuals could secure their release on their own recognizance if they committed to being accountable citizens and fulfilling their debts, whether monetary or moral.

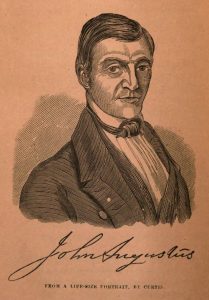

The origins of modern probation are often traced back to the 19th century and a businessperson named Jon Augustus, a bootmaker from Boston, Massachusetts. He is widely regarded as the father of probation due to his strong advocacy for abstaining from alcohol. Augustus was a dedicated member of the Washington Total Abstinence Society, which believed that individuals driven to crime by alcohol could be rehabilitated through kindness and moral guidance, rather than through imprisonment.

His active involvement started in 1841 when he appeared in a Boston police court to bail out a “common drunkard.” Three weeks later, Augustus attended the man’s court date, and those present were amazed by his transformation. In the early 1840s, Boston shoemaker John Augustus frequently visited the court and began overseeing individuals as a “Surety.” A Surety is someone who guarantees or pays for a person’s bond, allowing them to be released while awaiting trial. Augustus, depicted below (See Picture Below), took in many of these individuals, offering them jobs and housing to help keep them out of crime and repay society. He was sober and well-groomed. For 18 years, he voluntarily served as a probation officer.

Shortly after his death in 1859, a probation statute was enacted to ensure that his work could continue under the auspices of the state. With the rise of psychology’s influence in the 1920s, probation officers transitioned from providing practical assistance in the field to adopting a more therapeutic approach. The pendulum swung back to a more practical bent in the 1960s when probation officers began to act more as service brokers. They assisted probationers with tasks such as obtaining employment, securing housing, managing finances, and pursuing education.

Conditions of Probation

The primary goal of probation is to provide offenders with specific requirements that must be met to complete a court sanction and, importantly, to prevent them from being incarcerated for criminal violations. Due to a fragmented criminal justice system, each jurisdiction has standard conditions of probation that all probationers must follow, and judges typically have the authority to impose additional special conditions.

Probation serves a dual purpose: it requires offenders to meet specific conditions that not only mitigate risk to society but also address the individual needs of the offender. These two roles are instrumental in the probation process, striking a balance between public safety and the rehabilitation of offenders.

Standard conditions of probation generally include the following:

- Must not commit any new crimes and participate in any criminal activity.

- Will be required to report to a probation officer per the directions of the

- probation officer direction.

- May be required to maintain employment or show attempts to gain employment.

- May be required to submit to drug testing

- May be responsible for court-mandated financial obligations such as fees and fines.

- May be required to disassociate with known criminals.

Louisiana Special Requirements for Probation

- The defendant shall not leave the judicial district without the permission of the court or probation officer

- The defendant’s compliance with this condition is crucial. Failure to report to the probation officer and submit a truthful and complete written report within the first five days of each month may result in specific consequences

- The defendant shall answer truthfully all inquiries by the probation office and follow the instructions of the probation officer

- The defendant shall support his or her dependents and meet other family responsibilities

- The defendant shall work regularly at a lawful occupation. However, if the defendant needs to be excused for schooling, training, or other acceptable reasons, they must obtain permission from the probation officer

- The defendant shall notify the probation officer at least ten days prior to any change in residence or employment

- The defendant shall refrain from excessive use of alcohol and shall not purchase, use, distribute, or administer any controlled substance or any paraphernalia related to any controlled substances, except as prescribed by a physician

- The defendant shall not frequent places where controlled substances are illegally sold, used, distributed, or administered.

- The defendant shall not associate with any persons engaged in criminal activity. If the defendant wishes to associate with a person convicted of a felony, they must first obtain permission from the probation officer.

- The defendant shall permit a probation officer to visit him or her at any time at home or elsewhere and shall permit confiscation of any contraband observed in plain view by the probation officer

- The defendant shall notify the probation officer within seventy-two hours of being arrested or questioned by a law enforcement officer;

- The defendant shall not enter into any agreement to act as an informer or special agent of a law enforcement agency without permission of the court

- As directed by the probation officer, the defendant shall notify third parties of risks that may be occasioned by the defendant’s criminal record, personal history, or characteristics and shall permit the probation officer to make such notifications and confirm the defendant’s compliance with such notification required.

Louisiana Probation Requirements

Louisiana Probation and Parole – The Louisiana Interstate Compact

The Interstate Compact for the Supervision of People on Parole and Probation, established in 1937, was the first and only framework facilitating the controlled movement of adults on probation and parole across state lines. A significant milestone in this system’s evolution occurred with the ratification of the new Interstate Compact for Adult Offender Supervision on June 19, 2002, when Pennsylvania became the 35th state to adopt the updated Compact legislation. Louisiana was the 22nd state to enact the revised Compact law. All states, including the District of Columbia, the Virgin Islands, and Puerto Rico, are signatories to this Compact.

The new compact not only enhances public safety by ensuring that returning residents are adequately supervised, but also plays a crucial role in fostering accountability. Its regulations carry the full force and effect of statutory law and grant enforcement capabilities against states that fail to comply with its provisions. The Compact achieves this by including representatives from the legislative, executive, and judicial branches and victims’ rights advocates in a state oversight council. The Commission convenes annually to review regulations, develop policies, and provide training.

Louisiana, in its commitment to efficiency and modernization, employs the Interstate Compact Offender Tracking System (ICOTS), a national computer database that facilitates the compact process through a centralized, internet-based platform. This system not only enhances efficiency but also minimizes paperwork, making the process smoother and more streamlined.

The Louisiana Legislature has passed legislation authorizing a $150 application fee for individuals under community supervision who wish to transfer their supervision to another state. The fees collected offset the costs associated with returning those who violate probation or parole to Louisiana for revocation or court hearings. Louisiana aims to maintain a balanced number of incoming and outgoing transfer requests.

Louisiana employs the Interstate Compact Offender Tracking System (ICOTS), a national computer database that facilitates the compact process through a centralized, internet-based platform. This system enhances efficiency and minimizes paperwork.

The Louisiana Legislature has passed legislation authorizing a $150 application fee for individuals under community supervision who wish to transfer their supervision to another state. The fees collected offset the costs associated with returning those who violate probation or parole to Louisiana for revocation or court hearings. Louisiana aims to maintain a balanced number of incoming and outgoing transfer requests.

4.2 Officer Roles

Many jurisdictions combine the roles of probation and parole officers into a single job description. In Gagnon v. Scarpelli (1973), the court had this to say of the duties of such officers: “While the parole or probation officer responsibilities equate to double duty to the welfare of clients and to the safety of the general community, by and large, concern for the client dominates professional attitude of the officer. The parole agent role is ordinarily defined as one that represents the client’s best interests as long as these do not constitute a threat to public safety.” This statement suggests a dichotomy in the responsibility of parole (and probation) officers; they must look out for the client’s best interest and the public’s best interest. This fact frequently enters into politics. Liberals tend to focus on the treatment and rehabilitation of the offender, while conservatives prioritize public safety and just deserts for the offender.

From the court’s standpoint, parole officers are mandated to carry out law enforcement responsibilities aimed at ensuring public safety. Their duties, similar to those of police officers, encompass the enforcement of court orders involving drug testing, substance abuse treatment, alcohol rehabilitation, and anger management programs. Additionally, officers must provide testimony in court regarding their clients’ activities, perform searches, and collect evidence of illegal activities or technical breaches. When infractions take place, officers are frequently required to suggest actions, such as whether the offender should face imprisonment or remain on probation or parole under revised conditions.

There exists a divide regarding the function of probation and parole officers within the criminal justice system. This division arises from an artificial contrast, often framed as police work versus social work. The identification and enforcement of legal and Technical Violation are seen as integral to law enforcement, while the rehabilitation and reintegration of offenders are viewed as social work. Officers typically gravitate towards one of these roles more than the other. Some adopt a law enforcement standpoint, advocating for strict adherence to the law and parole regulations. Conversely, other officers see themselves primarily as counselors, assisting offenders in their reform and connecting them with community resources to address various issues. The personal beliefs of these officers, which greatly shape their professional demeanor, are frequently overlooked. Recognizing these beliefs can encourage empathy and a better understanding of the difficulties they encounter daily in their roles.

Probation Officers’ roles and responsibilities

Probation officers generally serve state or federal governments, but they can also work for local or municipal agencies. Many counties or parishes implement a community justice system that includes probation offices. In these offices, probation officers oversee cases, referred to as their caseload, which consists of probationers. The number of probationers in a probation officer’s caseload can vary widely, ranging from a few clients with significant needs or risks to several hundred probationers. This discrepancy is influenced by the jurisdiction, the local probation office’s structure, and the officers’ expertise.

The role of a probation officer (PO) is multifaceted and often involves conflicting duties. Their primary responsibility is to ensure compliance with probation terms. They achieve this through regular check-ins, administering random drug tests, and enforcing the conditions set for probationers. Additionally, POs may enter the field to serve warrants, conduct home compliance checks, and make arrests as needed.

Simultaneously, a probation officer strives to assist individuals on probation in achieving their goals. This includes helping them find employment, improve their education, and access programs for substance abuse and alcohol treatment, among other resources. The role of a probation officer is multifaceted and demands a balance between providing support and ensuring compliance. Recently, there has been a transformation in the field of probation, promoting a coaching mindset for officers rather than a strict enforcement role. This new strategy may contribute to decreased rates of probation revocation and recidivism.

Probation Officers are increasingly serving as “resource brokers,” helping probationers connect with vital resources to successfully complete their probation. Another important duty of a probation officer is to prepare PSI reports for individuals in the court system. A PSI, or Pre-Sentence Investigation report, is a psycho-social assessment for individuals facing trial. It offers essential background details about the person, such as age, education, relationships, physical and mental health, employment, military experience, social background, and substance use history. Furthermore, it contains a thorough account of the current offense, witness or victim impact statements related to the incident, and records of past offenses as documented by various agencies. Finally, the PSI includes a section for a supervision plan or recommendations from the probation officer, outlining appropriate probation conditions should probation be granted. Judges take this information into account during sentencing discussions and hearings, and they often follow the PSI’s recommendations. As a result, many probation conditions are set by probation officers.

The PSI includes key factors that determine if someone receives probation. If the offender is mainly a “prosocial” individual—possessing education, employment, and family connections—they are viewed as having strong community ties. Incarceration could jeopardize these ties. Therefore, offering a sanction that enables the offender to remain in the community is typically the favored option, depending on the specifics of the offense.

The Parole Officers’ responsibilities

To achieve the goals of parole, individuals released early from prison must comply with various conditions during their parole period. While these conditions may greatly limit activities beyond typical legal restrictions imposed on citizens, they are crucial for rehabilitation. Parolees are typically forbidden from drinking alcohol or using other intoxicants and from interacting with certain prohibited individuals (such as felons). Furthermore, they are usually required to seek approval from their parole officers before engaging in specific actions, including changing jobs or residences, getting married, acquiring or operating a vehicle, traveling outside the area, and taking on significant debt. Moreover, parolees are expected to regularly report to their parole officer.

Parole officers are vital to the administrative system, offering assistance and guidance to parolees. The conditions of parole serve two main purposes: they prohibit certain behaviors that are considered harmful to the individual’s reintegration into society, either absolutely or conditionally. Additionally, by requiring parolees to report to their officer and seek permission for various activities, the officer gains insights into the parolee’s behaviors and can provide relevant advice. This arrangement allows the parole officer to help guide the parolee toward constructive growth, establishing a supportive system for the individual.

The enforcement advantage supporting parole conditions stems from the authority to reincarcerate a parolee if they fail to comply with the rules. However, not all violations of parole conditions lead to immediate revocation. Generally, a parolee receives counseling to ensure compliance, and parole officers typically refrain from seeking revocation unless they believe the violations are significant and ongoing, indicating that the parolee struggles with adjustment and is likely to engage in antisocial behavior. The broad discretion given to parole officers is also reflected in some vague conditions, such as the usual requirement for parolees to avoid “undesirable” associations or correspondence. This discretionary power highlights the human aspect of the parole system, making it more relatable to the audience.

Case Study: Gagnon v. Scarpelli

In many jurisdictions, the roles of probation and parole officers are often merged into a single job. In Gagnon v. Scarpelli (1973), the court noted the responsibilities of these officers: “While the parole or probation officer recognizes his double duty to the welfare of his clients and to the safety of the general community, by and large, concern for the client dominates his professional attitude. The parole agent ordinarily defines his role as representing his client’s best interests as long as these do not constitute a threat to public safety.” This observation highlights a dual responsibility for parole and probation officers, as they must expertly navigate the interests of their clients while ensuring public safety. This dynamic often influences political debates, with liberals emphasizing treatment and rehabilitation for offenders, while conservatives prioritize public safety and appropriate punishment for offenders.

Gagnon v. Scarpelli is a significant 1973 U.S. Supreme Court case concerning the constitutional rights of those accused of probation violations. The Supreme Court determined that probationers have the right to a preliminary hearing prior to the revocation of their probation, followed by a final hearing. This ruling is based on the due process guarantees of the Fourteenth Amendment, which safeguards fairness in legal processes, particularly when an individual’s freedom is at stake.

The case involved two men, Gagnon and Scarpelli, who were on probation and faced potential revocation. They did not receive a hearing before their probation was revoked, leading to a legal challenge.

The Court determined that probationers have a due process right to a preliminary hearing to establish whether there is probable cause to believe they have violated the terms of their probation. They also have the right to a final hearing to present evidence before their probation can be revoked.

The decision established important guidelines for conducting probation revocation hearings, ensuring that individuals receive due process protections in this context. This case is significant for its impact on the rights of probationers within the U.S. legal system, particularly in safeguarding the right to a fair hearing before probation is revoked.

4.3 Intermediate Sanctions

Traditionally, a person convicted of an offense was sentenced to probation or prison. There was no middle ground. Intermediate sanctions seek that middle ground by providing a punishment that is more severe than probation alone yet less severe than an incarceration period. The most common among these alternatives is Intensive Supervision Probation (ISP). Offenders given this sort of intermediate sanction are assigned to an officer with a reduced caseload. Caseloads are reduced to give the officer more time to supervise each probationer. Frequent surveillance and frequent drug testing characterize most ISP programs. Offenders are usually chosen for these programs because they have been judged to be at a high risk of reoffending.

Another common alternative to prison is the work release program. These programs are designed to maintain environmental control over offenders while allowing them to remain in the workforce. Often, offenders sentenced to a work release program reside in a work release center, which a county jail can operate or which is part of the state prison system. Either way, work-release center residents can leave confinement for work-related purposes. Otherwise, they are locked in a secure facility.

A correctional Boot Camp is a facility run similarly to a military boot camp. Military-style discipline, structure, and rigorous physical training are the hallmarks of these programs. Usually, relatively young and nonviolent offenders are sentenced to terms ranging from three to six months in boot camps. Research has found that convicts view boot camps as more punitive than prison and would prefer a prison sentence to be sent to boot camps. Research has also shown that boot camp programs are no more effective at reducing long-term recidivism than other sanctions.

- Common alternatives to prison

- Correctional boot camps and military boot camps

4.4 Parole

The practice of releasing prisoners on parole before the end of their sentences has become an integral part of the correctional system in the United States. Parole is a variation of the imprisonment of convicted criminals. Its purpose is to help individuals reintegrate into society as productive members as soon as possible without requiring them to serve the full term of the sentence imposed by the courts. It also reduces the costs to society associated with keeping an individual in prison. The essence of parole is the release from prison before the completion of the sentence, on the condition that parolees adhere to specific rules during the remainder of their sentence. In some systems, parole is granted automatically after serving a specific portion of a prison term. Under others, parole is granted by the discretionary action of a board, which evaluates an array of information about a prisoner and makes a prediction of whether he is ready to reintegrate into society.

To accomplish the purpose of parole, those who are allowed to leave prison early are subjected to specified conditions for the duration of their parole. These conditions of parole restrict their activities substantially beyond the ordinary restrictions imposed by law on an individual citizen. Typically, parolees are forbidden to use alcohol and other intoxicants or to have associations or correspondence with certain categories of undesirable persons (such as felons). Typically, also they must seek permission from their parole officers before engaging in specified activities, such as changing employment or housing arrangements, marrying, acquiring or operating a motor vehicle, traveling outside the community, and incurring substantial indebtedness. Additionally, parolees must regularly report to their parole officer.

Case Study. Morrissey v. Brewer

In Morrissey v. Brewer (1972), the court established that individuals facing parole revocation are entitled to due process, which includes a prompt informal inquiry before an impartial hearing.

The court established a two-step procedure for revocation hearings. In the initial stage, a hearing officer assesses whether there is probable cause to suspect a violation has taken place. Parolees are entitled to be notified of the allegations against them, comprehend the evidence being shown, speak for themselves, present witnesses, and confront those testifying against them.

In the second stage, the formal revocation hearing, the paroled individual must receive notice of the charges and the disclosed evidence of the alleged violation. They are allowed to cross-examine witnesses. The hearing body then decides whether the violation is serious enough to warrant revocation. Ultimately, the individual must be provided with a written statement outlining the evidence considered and explaining the rationale behind the decision.

Morrissey v. Brewer, https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/408/471/]

4.5 Treatment

An “alternative to incarceration” refers to any form of punishment that does not involve imprisonment in a prison or jail for individuals who commit crimes. Often, these alternatives impose significant demands on offenders, providing intensive supervision from the court and community. Just because a punishment does not require time behind bars does not mean it is lenient or merely a “slap on the wrist.”

Alternatives to incarceration can mend the harm inflicted on victims, offer advantages to the community, tackle problems linked to drug addiction or mental health, and aid in the rehabilitation of offenders. Furthermore, these alternatives may result in lower expenses related to prisons and jails while also contributing to crime prevention.

To fully realize the benefits of alternatives to incarceration, it is crucial to repeal mandatory minimum sentences. This would enable courts to employ more cost-effective sentencing options that can help reduce recidivism.

4.6 Halfway Houses

Halfway Houses, referred to as “community correction centers” or “residential reentry centers” by the Federal Bureau of Prisons, primarily function as transitional housing for individuals reintegrating into the community following their prison sentences. They can also serve as alternatives to jail, especially for those facing shorter sentences. For instance, someone who has previously been incarcerated, released on parole, and then violated parole conditions might be mandated to spend some extra months in a halfway house rather than returning to prison. While living in a halfway house, individuals are monitored and must adhere to court-imposed conditions. Generally, they are required to remain at the facility except for court appearances or work commitments.

[INSERT FIGURE 4.2]

4.7 Home Confinement/ Electronic Home Monitoring

Home confinement, commonly called “house arrest,” mandates that offenders remain in their residences except for pre-approved locations like court or work. This setup typically includes electronic home monitoring (EHM), necessitating that offenders wear an electronic device, such as an ankle bracelet. This device continuously transmits a signal to a transmitter, enabling authorities to monitor the offender’s whereabouts at all times.

Home confinement, akin to probation, typically involves specific conditions. If an individual violates these conditions, they risk incarceration in jail or prison. Individuals on electronic home monitoring (EHM) generally check in with a probation officer daily and are subject to frequent and random drug screenings. In numerous jurisdictions, placement on EHM usually requires a recommendation from the court or a jail official.

4.8 Fines and Restitution

Imposing supervision fees, fines, and court costs on offenders can act as either an individual punishment or in conjunction with other penalties. “Tariff fines” are predetermined amounts set for specific offenses, such as $500 for driving under the influence, regardless of the offender’s financial status. These fines may carry little consequence for wealthy individuals, failing to act as a genuine deterrent. Conversely, tariff fines can create a significant financial burden for those with lower incomes, possibly leading to imprisonment if they cannot pay.

“Day fines” provide a more flexible approach to justice. Unlike fixed fines, day fines vary according to the severity of the crime and the offender’s daily income. This system ensures that wealthier offenders face penalties that impose a significant financial burden, while individuals with lower incomes pay amounts that are manageable for them, reducing the likelihood of incarceration.

Restitution requires offenders to reimburse some or all of the medical expenses or property losses incurred by the victim or community due to their crime.

[INSERT FIGURE 4.3]

4.9 Community Service

Community service can be its own punishment or act as a condition of probation or an alternative to paying restitution or a fine (each hour of service reduces the fine or restitution by a particular amount until it is paid in full). Community service is unpaid work by an offender for a civic or nonprofit organization. In federal courts, community service is not a sentence but a special condition of probation or supervised release.

4.10 Sex Offender Treatment and Civil Commitment

Many sex offenders are placed on probation, which requires them to participate in a sex offender treatment program, regularly report to a probation officer, avoid contacting their victims, refrain from using the internet, and stay away from specific areas for living or working. These treatment programs, whether conducted on an inpatient or outpatient basis, are vital for decreasing the chances of reoffending. They mainly incorporate cognitive-behavioral therapy, counseling, and various other techniques. Additionally, around 20 states implement “civil commitment” programs, which confine sex offenders to secure hospitals or residential treatment centers for ongoing care following their prison terms. This commitment can be indefinite, resulting in these programs being significantly more costly than incarceration. Recognizing these financial implications is crucial for ensuring that resources are allocated effectively.

4.11 Mental Health Courts

Mental health courts, similar to drug courts, serve a vital function in supporting recovery for individuals with mental illness, mental disabilities, drug dependency, or serious personality disorders. They offer a court-supervised, community-oriented mental health treatment program that integrates court and community oversight with either inpatient or outpatient professional mental health care. Offenders gain incentives for adhering to supervision stipulations and face consequences for failing to comply. These courts also connect participants to resources for housing, healthcare, and life skills training, which help reduce the risk of relapse and enhance recovery. It’s essential to understand that offenders must initially plead guilty to their charges before being redirected to mental health court, but the primary emphasis remains on their recovery possibilities.

4.12 Restorative Justice

Restorative Justice is a comprehensive sentencing approach that provides hope and healing for everyone affected by a crime, including the offender. It focuses not solely on punishment but on mending harm and restoring equilibrium. Members of the justice system, victims, offenders, and community participants collaborate to achieve these objectives through methods such as sentencing circles, victim restitution, victim-offender mediation, and structured community service programs. For example, sentencing circles convene the victim, offender, community members, and legal officials to collectively decide on a suitable sentence that addresses the harm caused. In victim-offender mediation, victims and offenders meet to offer apologies and seek forgiveness for the offense. Restorative justice strategies can be utilized independently or as part of a probationary requirement, providing a pathway to healing for all parties involved.

4.13 Boot Camp

Boot camp programs feature rigorous daily schedules that encompass physical workouts, individualized counseling, educational courses, and GED preparation. Presently, these boot camps have been phased out of the federal prison system and are infrequently utilized in state correctional facilities. Mirroring military boot camps, participants adhere to a strict disciplinary code, which mandates short haircuts and uniforms, standing at attention for officers, and addressing superiors as “sir.” Nonetheless, the possibility of early release after completing the program and securing employment can instill a sense of hope and motivation. Upon release, individuals may enter probation.

4.14 Public Shaming

Public shaming constitutes public humiliation, typically reserved for minor offenses. For instance, a convicted mail thief was ordered by a court to spend 100 hours outside a post office holding a sign that read, “I am a mail thief. This is my punishment.” The aim of public shaming is to rehabilitate the offender and deter future offenses.

4.15 Drug Courts

Drug Courts are a unique part of today’s judicial system, playing a key role in managing drug treatment and community supervision for individuals battling substance abuse. This management fosters a sense of order and reassurance. Although all 50 states and the District of Columbia have drug court initiatives, these fall outside the federal system. Some states operate drug courts for both adults and juveniles, along with family treatment courts or family dependency treatment courts, which focus on helping parents receive treatment to remain with or reunite with their children. Eligibility criteria and program features for drug courts differ from one area to another, but typically include some or all of the following: Requiring offenders to undergo random urine tests, participate in drug treatment counseling or attend Narcotics Anonymous/Alcoholics Anonymous meetings, meet with a probation officer, and report to the court regularly about their progress; Granting the court the power to commend and reward offenders for achievements or impose consequences for setbacks (which can include jail or prison time); and serving non-violent, substance-abusing offenders who meet particular eligibility criteria (for instance, having no history of violence and minimal prior convictions). Drug courts are not available at will. Generally, either the prosecutor or the presiding judge must refer the offender to drug court. Such a referral usually occurs only after the offender has pled guilty to the offense, and in some cases, it is a prerequisite for the referral. Some programs provide a beacon of hope for offenders. Those who successfully complete the program may avoid entering a guilty plea, having a conviction recorded, or serving part or all of their jail or prison sentences. Additionally, some programs enable successful participants who have pled guilty to have their drug convictions expunged, providing a fresh start and a renewed sense of hope.

Conclusion

This chapter explores the historical development of probation and parole, highlighting John Augustus’s influential role and advancements in community corrections during the 1960s. It analyzes the similarities and differences between probation and parole in various U.S. jurisdictions. The main objective of probation is to set specific requirements that offenders must meet as part of their court-mandated penalties. Beyond its primary role of imposing conditions that mitigate societal risk, probation also caters to the individual needs of the offender. Louisiana’s probation requirements are unique and follow the interstate compact established in 1937 for supervising parolees and probationers, which is the first and only framework for monitoring the movement of adults on probation and parole across state borders. This compact enhances public safety by providing adequate supervision to returning residents while promoting accountability among states.

In many jurisdictions, probation and parole responsibilities are combined into a single role; however, the Gagnon v. Scarpelli (1973) court decision noted that despite the dual focus of probation or parole officers on client welfare and community safety, concerns for the client usually take precedence. Additionally, the chapter emphasizes that historically, individuals convicted of crimes faced either probation or prison, with no alternatives. Intermediate sanctions introduce this necessary alternative by applying punishments that are harsher than probation but lighter than incarceration. Releasing prisoners on parole before completing their sentences has become an essential part of the U.S. correctional system, as parole acts as a form of managed release for convicted individuals. The chapter also reviews alternatives to incarceration, such as treatment at halfway houses, home confinement, electronic monitoring, and court-mandated fines and restitution. It further discusses restorative justice and specialized courts, like mental health and drug courts, aimed at addressing mental health and substance abuse offenses in relation to offender reintegration into society.

Discussion

- How did Jon Augustus’s contributions influence the implementation of probation in the correctional system?

- List and explain some conditions of probation.

- Discuss the roles and responsibilities of probation officers.

- How do probation and parole facilitate rehabilitation and help correct offenders?

- How has the ruling in Gagnon v. Scarpelli affected probation and parole in the criminal justice system?

- What are some of Louisiana’s special requirements for probation?

- Explain the significance of the Morrissey v. Brewer case.

- Discuss the impacts of the Louisiana Interstate Compact.

- Discuss home confinement and mandates for offenders.

- Discuss the roles of drug courts and how probation and parole relate to this specialized court.

Media Attributions

- Fig 4.1 © Prince, J. (1848). A wreath for St. Crispin: being sketches of eminent shoemakers. Boston: Bela Marsh. is licensed under a Public Domain license

A penalty that allows convicted criminals to be monitored in the community and requires them to follow specific rules and restrictions.

Gollowing incarceration, conditions of release, under supervision, are subject to specific rules.

For probation and parole, these are actions of the offender that do not comply with the requirements or conditions of supervision

Penalties or criminal punishments that lie between incarceration and probation.

Boot camp is a demanding corrections-focused program featuring daily routines that include physical workouts, personalized counseling, and educational courses.

A type of community correctional program for individuals reintegration into society after incarceration.

Unlike retributive justice which emphasizes punishment, restorative justice is an alternative justice approach which focuses on repairing the harm caused by crimes through mediation involving offender accountability, healing and forgiveness by all parties to the crime namely the victims, offenders and the community

These are specialized courts where individuals with minor drug possession offenses are diverted and granted access to treatment programs in lieu of incarceration.