56 Approaches and Measurements

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section you should be able to:

- Describe what MMPI is and how people use MMPI to measure personalities.

- Describe various projective tests.

- Discuss how personality may differ across cultures.

- Discuss ways to study personalities across cultures.

The MMPI and Projective Tests

One of the most important measures of personality (which is used primarily to assess deviations from a “normal” or “average” personality) is the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI), a test used around the world to identify personality and psychological disorders (Tellegen et al., 2003). The MMPI was developed by creating a list of more than 1,000 true-false questions and choosing those that best differentiated patients with different psychological disorders from other people. The current version (the MMPI-2) has more than 500 questions, and the items can be combined into a large number of different subscales. Some of the most important of these are shown in the table, Some of the Major Subscales of the MMPI, but there are also scales that represent family problems, work attitudes, and many other dimensions. The MMPI also has questions that are designed to detect the tendency of the respondents to lie, fake, or simply not answer the questions.

Some of the Major Subscales of the MMPI

| Abbreviation | Description | What is measured | No. of items |

| Hs | Hypochondriasis | Concern with bodily symptoms | 32 |

| D | Depression | Depressive symptoms | 57 |

| Hy | Hysteria | Awareness of problems and vulnerabilities | 60 |

| Pd | Psychopathic deviate | Conflict, struggle, anger, respect for society’s rules | 50 |

| MF | Masculinity/femininity | Stereotypical masculine or feminine interests/behaviors | 56 |

| Pa | Paranoia | Level of trust, suspiciousness, sensitivity | 40 |

| Pt | Psychasthenia | Worry, anxiety, tension, doubts, obsessiveness | 48 |

| Sc | Schizophrenia | Odd thinking and social alienation | 78 |

| Ma | Hypomania | Level of excitability | 46 |

| Si | Social introversion | People orientation | 69 |

To interpret the results, the clinician looks at the pattern of responses across the different subscales and makes a diagnosis about the potential psychological problems facing the patient. Although clinicians prefer to interpret the patterns themselves, a variety of research has demonstrated that computers can often interpret the results as well as can clinicians (Garb, 1998; Karon, 2000). Extensive research has found that the MMPI-2 can accurately predict which of many different psychological disorders a person suffers from (Graham, 2006).

One potential problem with a measure like the MMPI is that it asks people to consciously report on their inner experiences. But much of our personality is determined by unconscious processes of which we are only vaguely or not at all aware. Projective measures are measures of personality in which unstructured stimuli, such as inkblots, drawings of social situations, or incomplete sentences, are shown to participants, who are asked to freely list what comes to mind as they think about the stimuli. Experts then score the responses for clues to personality. The proposed advantage of these tests is that they are more indirect—they allow the respondent to freely express whatever comes to mind, including perhaps the contents of their unconscious experiences.

One commonly used projective test is the Rorschach Inkblot Test, developed by the Swiss psychiatrist Hermann Rorschach (1884–1922). The Rorschach Inkblot Test is a projective measure of personality in which the respondent indicates his or her thoughts about a series of 10 symmetrical inkblots. The Rorschach is administered millions of times every year. The participants are asked to respond to the inkblots, and their responses are systematically scored in terms of what, where, and why they saw what they saw. For example, people who focus on the details of the inkblots may have obsessive-compulsive tendencies, whereas those who talk about sex or aggression may have sexual or aggressive problems.

Rorschach Inkblots

Another frequently administered projective test is the Thematic Apperception Test (TAT), developed by the psychologist Henry Murray (1893–1988). The Thematic Apperception Test (TAT) is a projective measure of personality in which the respondent is asked to create stories about sketches of ambiguous situations, most of them of people, either alone or with others. The sketches are shown to individuals, who are asked to tell a story about what is happening in the picture. The TAT assumes that people may be unwilling or unable to admit their true feelings when asked directly but that these feelings will show up in the stories about the pictures. Trained coders read the stories and use them to develop a personality profile of the respondent.

Other popular projective tests include those that ask the respondent to draw pictures, such as the Draw- A-Person test (Machover, 1949), and free association tests in which the respondent quickly responds with the first word that comes to mind when the examiner says a test word. Another approach is the use of “anatomically correct” dolls that feature representations of the male and female genitals. Investigators allow children to play with the dolls and then try to determine on the basis of the play if the children may have been sexually abused.

The advantage of projective tests is that they are less direct, allowing people to avoid using their defense mechanisms and therefore show their “true” personality. The idea is that when people view ambiguous stimuli they will describe them according to the aspects of personality that are most important to them, and therefore bypass some of the limitations of more conscious responding.

Despite their widespread use, however, the empirical evidence supporting the use of projective tests is mixed (Karon, 2000; Wood, Nezworski, Lilienfeld, & Garb, 2003). The reliability of the measures is low because people often produce very different responses on different occasions. The construct validity of the measures is also suspect because there are very few consistent associations between Rorschach scores or TAT scores and most personality traits. The projective tests often fail to distinguish between people with psychological disorders and those without or to correlate with other measures of personality or with behavior.

In sum, projective tests are more useful as icebreakers to get to know a person better, to make the person feel comfortable, and to get some ideas about topics that may be of importance to that person than for accurately diagnosing personality.

Psychology in Everyday Life: Leaders and Leadership

One trait that has been studied in thousands of studies is leadership, the ability to direct or inspire others to achieve goals. Trait theories of leadership are theories based on the idea that some people are simply “natural leaders” because they possess personality characteristics that make them effective (Zaccaro, 2007). Consider Steve Jobs, the founder of Apple, shown in the figure “Varieties of Leaders.” What characteristics do you think he possessed that allowed him to create such a strong company, even though many similar companies failed?

Varieties of Leaders

Research has found that being intelligent is an important characteristic of leaders, as long as the leader communicates to others in a way that is easily understood by his or her followers (Simonton, 1994, 1995). Other research has found that people with good social skills, such as the ability to accurately perceive the needs and goals of the group members and to communicate with others, also tend to make good leaders (Kenny & Zaccaro, 1983).

Because so many characteristics seem to be related to leader skills, some researchers have attempted to account for leadership not in terms of individual traits, but rather in terms of a package of traits that successful leaders seem to have. Some have considered this in terms of charisma (Sternberg & Lubart, 1995; Sternberg, 2002). Charismatic leaders are leaders who are enthusiastic, committed, and self-confident; who tend to talk about the importance of group goals at a broad level; and who make personal sacrifices for the group. Charismatic leaders express views that support and validate existing group norms but that also contain a vision of what the group could or should be. Charismatic leaders use their referent power to motivate, uplift, and inspire others. And research has found a positive relationship between a leader’s charisma and effective leadership performance (Simonton, 1988).

Another trait-based approach to leadership is based on the idea that leaders take either transactional or transformational leadership styles with their subordinates (Bass, 1999; Pieterse, Van Knippenberg, Schippers, & Stam, 2010). Transactional leaders are the more regular leaders, who work with their subordinates to help them understand what is required of them and to get the job done. Transformational leaders, on the other hand, are more like charismatic leaders—they have a vision of where the group is going, and attempt to stimulate and inspire their workers to move beyond their present status and to create a new and better future.

Despite the fact that there appear to be at least some personality traits that relate to leadership ability, the most important approaches to understanding leadership take into consideration both the personality characteristics of the leader as well as the situation in which the leader is operating. In some cases the situation itself is important. For instance, you might remember that President George W. Bush’s ratings as a leader increased dramatically after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center. This is a classic example of how a situation can influence the perceptions of a leader’s skill.

In still other cases, different types of leaders may perform differently in different situations. Leaders whose personalities lead them to be more focused on fostering harmonious social relationships among the members of the group, for instance, are particularly effective in situations in which the group is already functioning well and yet it is important to keep the group members engaged in the task and committed to the group outcomes. Leaders who are more task-oriented and directive, on the other hand, are more effective when the group is not functioning well and needs a firm hand to guide it (Ayman, Chemers, & Fiedler, 1995).

As you have learned in this chapter, personality is shaped by both genetic and environmental factors. The culture in which you live is one of the most important environmental factors that shapes your personality (Triandis & Suh, 2002). The term culture refers to all of the beliefs, customs, art, and traditions of a particular society. Culture is transmitted to people through language as well as through the modeling of culturally acceptable and nonacceptable behaviors that are either rewarded or punished (Triandis & Suh, 2002). With these ideas in mind, personality psychologists have become interested in the role of culture in understanding personality. They ask whether personality traits are the same across cultures or if there are variations. It appears that there are both universal and culture-specific aspects that account for variation in people’s personalities.

Why might it be important to consider cultural influences on personality? Western ideas about personality may not be applicable to other cultures (Benet-Martinez & Oishi, 2008). In fact, there is evidence that the strength of personality traits varies across cultures. Let’s take a look at some of the Big Five factors (conscientiousness, neuroticism, openness, and extroversion) across cultures. As you will learn when you study social psychology, Asian cultures are more collectivist, and people in these cultures tend to be less extroverted. People in Central and South American cultures tend to score higher on openness to experience, whereas Europeans score higher on neuroticism (Benet-Martinez & Karakitapoglu-Aygun, 2003).

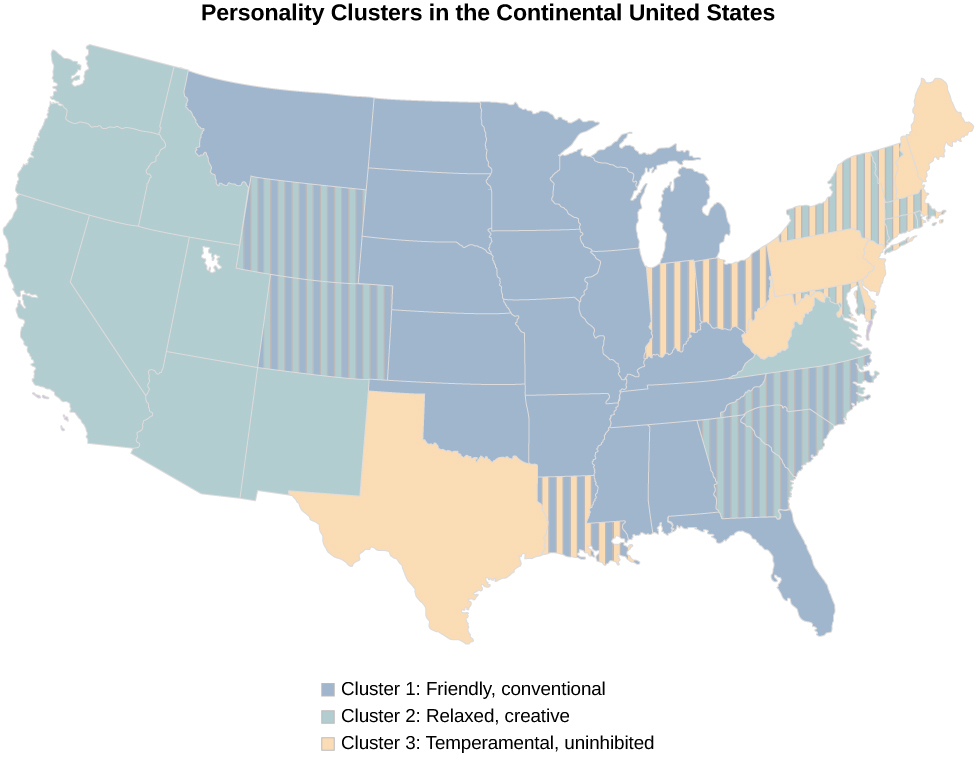

According to this study, there also seem to be regional personality differences within the United States. Researchers analyzed responses from over 1.5 million individuals in the United States and found that there are three distinct regional personality clusters: Cluster 1, which is in the Upper Midwest and Deep South, is dominated by people who fall into the “friendly and conventional” personality; Cluster 2, which includes the West, is dominated by people who are more relaxed, emotionally stable, calm, and creative; and Cluster 3, which includes the Northeast, has more people who are stressed, irritable, and depressed. People who live in Clusters 2 and 3 are also generally more open (Rentfrow et al., 2013).

One explanation for the regional differences is selective migration (Rentfrow et al., 2013). Selective migration is the concept that people choose to move to places that are compatible with their personalities and needs. For example, a person high on the agreeable scale would likely want to live near family and friends, and would choose to settle or remain in such an area. In contrast, someone high on openness would prefer to settle in a place that is recognized as diverse and innovative (such as California).

Personality in Individualist and Collectivist Cultures

Individualist cultures and collectivist cultures place emphasis on different basic values. People who live in individualist cultures tend to believe that independence, competition, and personal achievement are important. Individuals in Western nations such as the United States, England, and Australia score high on individualism (Oyserman, Coon, & Kemmelmier, 2002). People who live in collectivist cultures value social harmony, respectfulness, and group needs over individual needs. Individuals who live in countries in Asia, Africa, and South America score high on collectivism (Hofstede, 2001; Triandis, 1995). These values influence personality. For example, Yang (2006) found that people in individualist cultures displayed more personally oriented personality traits, whereas people in collectivist cultures displayed more socially oriented personality traits.

Approaches to Studying Personality in a Cultural Context

There are three approaches that can be used to study personality in a cultural context, the cultural-comparative approach; the indigenous approach; and the combined approach, which incorporates elements of both views. Since ideas about personality have a Western basis, the cultural-comparative approach seeks to test Western ideas about personality in other cultures to determine whether they can be generalized and if they have cultural validity (Cheung van de Vijver, & Leong, 2011). For example, recall from the previous section on the trait perspective that researchers used the cultural-comparative approach to test the universality of McCrae and Costa’s Five Factor Model. They found applicability in numerous cultures around the world, with the Big Five traits being stable in many cultures (McCrae & Costa, 1997; McCrae et al., 2005). The indigenous approach came about in reaction to the dominance of Western approaches to the study of personality in non-Western settings (Cheung et al., 2011). Because Western-based personality assessments cannot fully capture the personality constructs of other cultures, the indigenous model has led to the development of personality assessment instruments that are based on constructs relevant to the culture being studied (Cheung et al., 2011). The third approach to cross-cultural studies of personality is the combined approach, which serves as a bridge between Western and indigenous psychology as a way of understanding both universal and cultural variations in personality (Cheung et al., 2011).

Test Your Understanding

Summary

The culture in which you live is one of the most important environmental factors that shapes your personality. Western ideas about personality may not be applicable to other cultures. In fact, there is evidence that the strength of personality traits varies across cultures. Individualist cultures and collectivist cultures place emphasis on different basic values. People who live in individualist cultures tend to believe that independence, competition, and personal achievement are important. People who live in collectivist cultures value social harmony, respectfulness, and group needs over individual needs. There are three approaches that can be used to study personality in a cultural context: the cultural-comparative approach, the indigenous approach, and the combined approach, which incorporates both elements of both views.

Review Questions

Critical Thinking Questions

Why might it be important to consider cultural influences on personality?

Since culture influences one’s personality, then Western ideas about personality may not be applicable to people of other cultures. In addition, Western-based measures of personality assessment may not be valid when used to collect data on people from other cultures.

Personal Application Questions

According to the work of Rentfrow and colleagues, personalities are not randomly distributed. Instead they fit into distinct geographic clusters. Based on where you live, do you agree or disagree with the traits associated with yourself and the residents of your area of the country? Why or why not?

a test used around the world to identify personality and psychological disorders

measures of personality in which unstructured stimuli, such as inkblots, drawings of social situations, or incomplete sentences, are shown to participants, who are asked to freely list what comes to mind as they think about the stimuli

a projective measure of personality in which the respondent indicates his or her thoughts about a series of 10 symmetrical inkblots

a projective measure of personality in which the respondent is asked to create stories about sketches of ambiguous situations, most of them of people, either alone or with others

the ability to direct or inspire others to achieve goals

leaders who are enthusiastic, committed, and self-confident; who tend to talk about the importance of group goals at a broad level; and who make personal sacrifices for the group