55 Personality and Behavior

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the trait approach to understanding personality and the influences of personality on behaviors.

- Discuss how situations play a role in one’s personality.

Personality as Traits

One approach to examine the influence of personality on behaviors is the trait approach. Personalities are characterized in terms of traits, which are relatively enduring characteristics that influence our behavior across many situations. Personality traits such as introversion, friendliness, conscientiousness, honesty, and helpfulness are important because they help explain consistencies in behavior.

The most popular way of measuring traits is by administering personality tests on which people self-report about their own characteristics. Psychologists have investigated hundreds of traits using the self-report approach, and this research has found many personality traits that have important implications for behavior. You can see some examples of the personality dimensions that have been studied by psychologists and their implications for behavior in the table, Some Personality Traits That Predict Behavior.

Some Personality Traits That Predict Behavior

| Trait | Description | Examples of behaviors exhibited by people who have the trait |

|---|---|---|

| Authoritarianism (Adorno, Frenkel-Brunswik, Levinson, & Sanford, 1950) | A cluster of traits including conventionalism, superstition, toughness, and exaggerated concerns with sexuality | Authoritarians are more likely to be prejudiced, to conform to leaders, and to display rigid behaviors. |

| Individualism-collectivism (Triandis, 1989) | Individualism is the tendency to focus on oneself and one’s personal goals; collectivism is the tendency to focus on one’s relations with others. | Individualists prefer to engage in behaviors that make them stand out from others, whereas collectivists prefer to engage in behaviors that emphasize their similarity to others. |

| Internal versus external locus of control (Rotter, 1966) | In comparison to those with an external locus of control, people with an internal locus of control are more likely to believe that life events are due largely to their own efforts and personal characteristics. | People with higher internal locus of control are happier, less depressed, and healthier in comparison to those with an external locus of control. |

| Need for achievement (McClelland, 1958) | The desire to make significant accomplishments by mastering skills or meeting high standards | Those high in need for achievement select tasks that are not too difficult to be sure they will succeed in them. |

| Need for cognition (Cacioppo & Petty, 1982) | The extent to which people engage in and enjoy effortful cognitive activities | People high in the need for cognition pay more attention to arguments in ads. |

| Regulatory focus (Shah, Higgins, & Friedman, 1998) | Refers to differences in the motivations that energize behavior, varying from a promotion orientation (seeking out new opportunities) to a prevention orientation (avoiding negative outcomes) | People with a promotion orientation are more motivated by goals of gaining money, whereas those with prevention orientation are more concerned about losing money. |

| Self-consciousness (Fenigstein, Sheier, & Buss, 1975) | The tendency to introspect and examine one’s inner self and feelings | People high in self-consciousness spend more time preparing their hair and makeup before they leave the house. |

| Self-esteem (Rosenberg, 1965) | High self-esteem means having a positive attitude toward oneself and one’s capabilities. | High self-esteem is associated with a variety of positive psychological and health outcomes. |

| Sensation seeking (Zuckerman, 2007) | The motivation to engage in extreme and risky behaviors | Sensation seekers are more likely to engage in risky behaviors such as extreme and risky sports, substance abuse, unsafe sex, and crime. |

Sources: Adorno, T. W., Frenkel-Brunswik, E., Levinson, D. J., & Sanford, R. N. (1950). The authoritarian personality. New York, NY: Harper; Triandis, H. (1989). The self and social behavior in differing cultural contexts. Psychological Review, 93, 506–520; Rotter, J. (1966). Generalized expectancies of internal versus external locus of control of reinforcement. Psychological Monographs, 80; McClelland, D. C. (1958). Methods of measuring human motivation. In John W. Atkinson (Ed.), Motives in fantasy, action and society. Princeton, NJ: D. Van Nostrand; Cacioppo, J. T., & Petty, R. E. (1982). The need for cognition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 42, 116–131; Shah, J., Higgins, T., & Friedman, R. S. (1998). Performance incentives and means: How regulatory focus influences goal attainment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(2), 285–293; Fenigstein, A., Scheier, M. F., & Buss, A. H. (1975). Public and private self-consciousness: Assessment and theory. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 43, 522–527; Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; Zuckerman, M. (2007). Sensation seeking and risky behavior. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

As with intelligence tests, the utility of self-report measures of personality depends on their reliability and construct validity. Some popular measures of personality are not useful because they are unreliable or invalid. Perhaps you have heard of a personality test known as the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI). If so, you are not alone, because the MBTI is the most widely administered personality test in the world, given millions of times a year to employees in thousands of companies. The MBTI categorizes people into one of four categories on each of four dimensions: introversion versus extroversion, sensing versus intuiting, thinking versus feeling, and judging versus perceiving.

Although completing the MBTI can be useful for helping people think about individual differences in personality, and for “breaking the ice” at meetings, the measure itself is not psychologically useful because it is not reliable or valid. People’s classifications change over time and scores on the MBTI do not relate to other measures of personality or to behavior (Hunsley, Lee, & Wood, 2003). Measures such as the MBTI remind us that it is important to scientifically and empirically test the effectiveness of personality tests by assessing their stability over time and their ability to predict behavior.

One of the challenges of the trait approach to personality is that there are so many of them; there are at least 18,000 English words that can be used to describe people (Allport & Odbert, 1936). Thus a major goal of psychologists is to take this vast number of descriptors (many of which are very similar to each other) and to determine the underlying important or “core” traits among them (John, Angleitner, & Ostendorf, 1988).

The trait approach to personality was pioneered by early psychologists, including Gordon Allport (1897–1967), Raymond Cattell (1905–1998), and Hans Eysenck (1916–1997). Each of these psychologists believed in the idea of the trait as the stable unit of personality, and each attempted to provide a list or taxonomy of the most important trait dimensions. Their approach was to provide people with a self-report measure and then to use statistical analyses to look for the underlying “factors” or “clusters” of traits, according to the frequency and the co-occurrence of traits in the respondents.

Allport (1937) began his work by reducing the 18,000 traits to a set of about 4,500 traitlike words that he organized into three levels according to their importance. He called them “cardinal traits” (the most important traits), “central traits” (the basic and most useful traits), and “secondary traits” (the less obvious and less consistent ones). Cattell (1990) used a statistical procedure known as factor analysis to analyze the correlations among traits and to identify the most important ones. On the basis of his research he identified what he referred to as “source” (more important) and “surface” (less important) traits, and he developed a measure that assessed 16 dimensions of traits based on personality adjectives taken from everyday language.

Hans Eysenck was particularly interested in the biological and genetic origins of personality and made an important contribution to understanding the nature of a fundamental personality trait: extraversion versus introversion (Eysenck, 1998). Eysenck proposed that people who are extroverted (i.e., who enjoy socializing with others) have lower levels of naturally occurring arousal than do introverts (who are less likely to enjoy being with others). Eysenck argued that extroverts have a greater desire to socialize with others to increase their arousal level, which is naturally too low, whereas introverts, who have naturally high arousal, do not desire to engage in social activities because they are overly stimulating.

The fundamental work on trait dimensions conducted by Allport, Cattell, Eysenck, and many others has led to contemporary trait models, the most important and well-validated of which is the Five-Factor (Big Five) Model of Personality. According to this model, there are five fundamental underlying trait dimensions that are stable across time, cross-culturally shared, and explain a substantial proportion of behavior (Costa & McCrae, 1992; Goldberg, 1982). As you can see in the table, The Five Factors of the Five-Factor Model of Personality, the five dimensions (sometimes known as the “Big Five”) are agreeableness, conscientiousness, extraversion, neuroticism, and openness to experience. (You can remember them using the watery acronyms CANOE or OCEAN.)

The Five Factors of the Five-Factor Model of Personality

| Dimension | Sample items | Description | Examples of behaviors predicted by the trait |

|---|---|---|---|

| Openness to experience | “I have a vivid imagination”; “I have a rich vocabulary”; “I have excellent ideas.” | A general appreciation for art, emotion, adventure, unusual ideas, imagination, curiosity, and variety of experience | Individuals who are highly open to experience tend to have distinctive and unconventional decorations in their home. They are also likely to have books on a wide variety of topics, a diverse music collection, and works of art on display. |

| Conscientiousness | “I am always prepared”; “I am exacting in my work”; “I follow a schedule.” | A tendency to show self-discipline, act dutifully, and aim for achievement | Individuals who are conscientious have a preference for planned rather than spontaneous behavior. |

| Extraversion | “I am the life of the party”; “I feel comfortable around people”; “I talk to a lot of different people at parties.” | The tendency to experience positive emotions and to seek out stimulation and the company of others | Extroverts enjoy being with people. In groups they like to talk, assert themselves, and draw attention to themselves. |

| Agreeableness | “I am interested in people”; “I feel others’ emotions”; “I make people feel at ease.” | A tendency to be compassionate and cooperative rather than suspicious and antagonistic toward others; reflects individual differences in general concern for social harmony | Agreeable individuals value getting along with others. They are generally considerate, friendly, generous, helpful, and willing to compromise their interests with those of others. |

| Neuroticism | “I am not usually relaxed”; “I get upset easily”; “I am easily disturbed” | The tendency to experience negative emotions, such as anger, anxiety, or depression; sometimes called “emotional instability” | Those who score high in neuroticism are more likely to interpret ordinary situations as threatening and minor frustrations as hopelessly difficult. They may have trouble thinking clearly, making decisions, and coping effectively with stress. |

A large body of research evidence has supported the five-factor model. The Big Five dimensions seem to be cross-cultural, because the same five factors have been identified in participants in China, Japan, Italy, Hungary, Turkey, and many other countries (Triandis & Suh, 2002). The Big Five dimensions also accurately predict behavior. For instance, a pattern of high conscientiousness, low neuroticism, and high agreeableness predicts successful job performance (Tett, Jackson, & Rothstein, 1991). Scores on the Big Five dimensions also predict the performance of U.S. presidents; ratings of openness to experience are correlated positively with ratings of presidential success, whereas ratings of agreeableness are correlated negatively with success (Rubenzer, Faschingbauer, & Ones, 2000). The Big Five factors are also increasingly being used in helping researchers understand the dimensions of psychological disorders such as anxiety and depression (Oldham, 2010; Saulsman & Page, 2004).

An advantage of the five-factor approach is that it is parsimonious. Rather than studying hundreds of traits, researchers can focus on only five underlying dimensions. The Big Five may also capture other dimensions that have been of interest to psychologists. For instance, the trait dimension of need for achievement relates to the Big Five variable of conscientiousness, and self-esteem relates to low neuroticism. On the other hand, the Big Five factors do not seem to capture all the important dimensions of personality. For instance, the Big Five does not capture moral behavior, although this variable is important in many theories of personality. And there is evidence that the Big Five factors are not exactly the same across all cultures (Cheung & Leung, 1998).

Situational Influences on Personality

One challenge to the trait approach to personality is that traits may not be as stable as we think they are. When we say that Malik is friendly, we mean that Malik is friendly today and will be friendly tomorrow and even next week. And we mean that Malik is friendlier than average in all situations. But what if Malik were found to behave in a friendly way with his family members but to be unfriendly with his fellow classmates? This would clash with the idea that traits are stable across time and situation.

The psychologist Walter Mischel (1968) reviewed the existing literature on traits and found that there was only a relatively low correlation (about r = .30) between the traits that a person expressed in one situation and those that they expressed in other situations. In one relevant study, Hartshorne, May, Maller, & Shuttleworth (1928) examined the correlations among various behavioral indicators of honesty in children. They also enticed children to behave either honestly or dishonestly in different situations, for instance, by making it easy or difficult for them to steal and cheat. The correlations among children’s behavior was low, generally less than r = .30, showing that children who steal in one situation are not always the same children who steal in a different situation. And similar low correlations were found in adults on other measures, including dependency, friendliness, and conscientiousness (Bem & Allen, 1974).

Psychologists have proposed two possibilities for these low correlations. One possibility is that the natural tendency for people to see traits in others leads us to believe that people have stable personalities when they really do not. In short, perhaps traits are more in the heads of the people who are doing the judging than they are in the behaviors of the people being observed. The fact that people tend to use human personality traits, such as the Big Five, to judge animals in the same way that they use these traits to judge humans is consistent with this idea (Gosling, 2001). And this idea also fits with research showing that people use their knowledge representation (schemas) about people to help them interpret the world around them and that these schemas color their judgments of others’ personalities (Fiske & Taylor, 2007).

Research has also shown that people tend to see more traits in other people than they do in themselves. You might be able to get a feeling for this by taking the following short quiz. First, think about a person you know—your mom, your roommate, or a classmate—and choose which of the three responses on each of the four lines best describes him or her. Then answer the questions again, but this time about yourself.

| 1. | Energetic | Relaxed | Depends on the situation |

| 2. | Skeptical | Trusting | Depends on the situation |

| 3. | Quiet | Talkative | Depends on the situation |

| 4. | Intense | Calm | Depends on the situation |

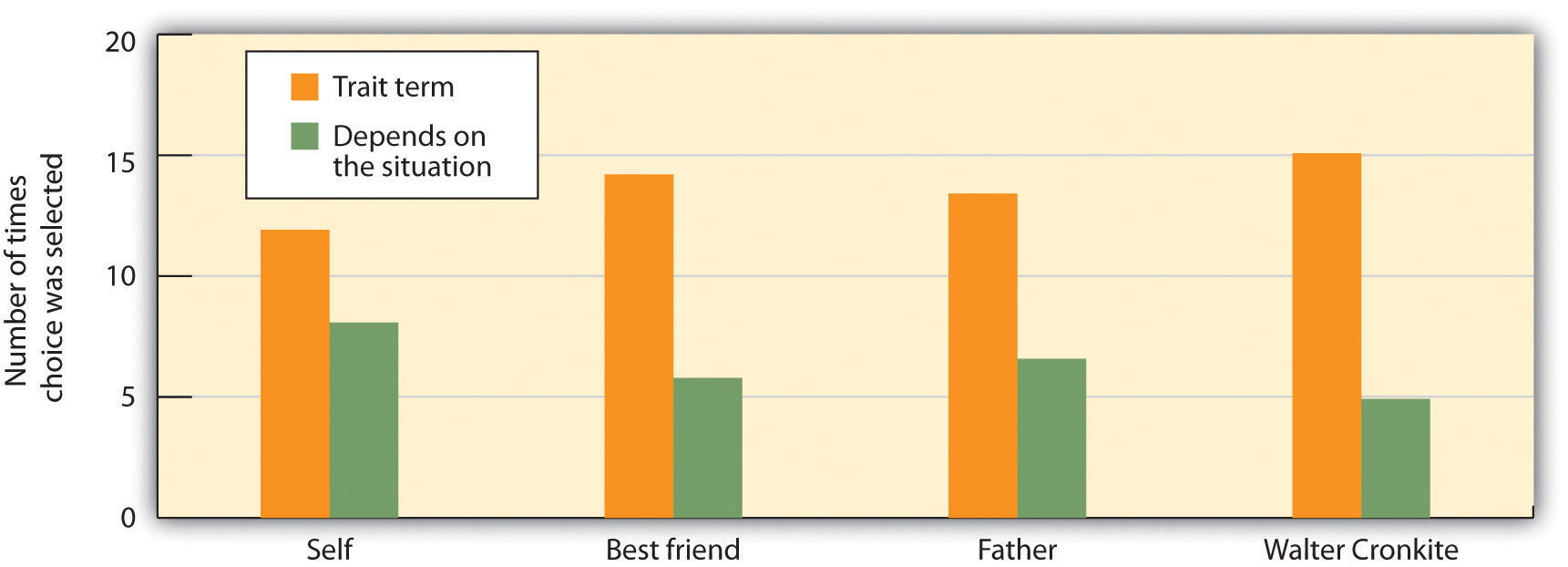

Richard Nisbett and his colleagues (Nisbett, Caputo, Legant, & Marecek, 1973) had college students complete this same task for themselves, for their best friend, for their father, and for the (at the time well-known) newscaster Walter Cronkite. As you can see in the figure, We Tend to Overestimate the Traits of Others, the participants chose one of the two trait terms more often for other people than they did for themselves, and chose “depends on the situation” more frequently for themselves than they did for the other people. These results also suggest that people may perceive more consistent traits in others than they should.

We Tend to Overestimate the Traits of Others

The human tendency to perceive traits is so strong that it is very easy to convince people that trait descriptions of themselves are accurate. Imagine that you had completed a personality test and the psychologist administering the measure gave you this description of your personality:

I would imagine that you might find that it described you. You probably do criticize yourself at least sometimes, and you probably do sometimes worry about things. The problem is that you would most likely have found some truth in a personality description that was the opposite. Could this description fit you too?

The Barnum effect refers to the observation that people tend to believe in descriptions of their personality that supposedly are descriptive of them but could in fact describe almost anyone. The Barnum effect helps us understand why many people believe in astrology, horoscopes, fortune-telling, palm reading, tarot card reading, and even some personality tests. People are likely to accept descriptions of their personality if they think that they have been written for them, even though they cannot distinguish their own tarot card or horoscope readings from those of others at better than chance levels (Hines, 2003). Again, people seem to believe in traits more than they should.

A second way that psychologists responded to Mischel’s findings was by searching even more carefully for the existence of traits. One insight was that the relationship between a trait and a behavior is less than perfect because people can express their traits in different ways (Mischel & Shoda, 2008). People high in extraversion, for instance, may become teachers, salesmen, actors, or even criminals. Although the behaviors are very different, they nevertheless all fit with the meaning of the underlying trait.

Psychologists also found that, because people do behave differently in different situations, personality will only predict behavior when the behaviors are aggregated or averaged across different situations. We might not be able to use the personality trait of openness to experience to determine what Saul will do on Friday night, but we can use it to predict what he will do over the next year in a variety of situations. When many measurements of behavior are combined, there is much clearer evidence for the stability of traits and for the effects of traits on behavior (Roberts & DelVecchio, 2000; Srivastava, John, Gosling, & Potter, 2003).

Taken together, these findings make a very important point about personality, which is that it not only comes from inside us but is also shaped by the situations that we are exposed to. Personality is derived from our interactions with and observations of others, from our interpretations of those interactions and observations, and from our choices of which social situations we prefer to enter or avoid (Bandura, 1986). In fact, behaviorists such as B. F. Skinner explain personality entirely in terms of the environmental influences that the person has experienced. Because we are profoundly influenced by the situations that we are exposed to, our behavior does change from situation to situation, making personality less stable than we might expect. And yet personality does matter—we can, in many cases, use personality measures to predict behavior across situations.

relatively enduring characteristics that influence our behavior across many situations

five fundamental underlying trait dimensions that are stable across time, cross-culturally shared, and explain a substantial proportion of behavior

the observation that people tend to believe in descriptions of their personality that supposedly are descriptive of them but could in fact describe almost anyone