1 The Nature of Science

Scientific Method and Measurement

Chapter Learning Objectives

After successful completion of the assignments in this section, you will be able to demonstrate competency in the following areas:

- List and use the steps of the scientific method (CLO2)(CLO4)

- Estimate physical parameters (CLO2)(CLO3)(CLO5)

- Solve simple problems using derived quantities (CLO2)(CLO5)

- Recognize and use SI base units and prefixes (CLO2)(CLO5)

- Convert from one unit system to another (CLO2)(CLO5)

- Use dimensional analysis to check the consistency of your work (CLO5)

The Nature of Science

Science is an overarching category of many different disciplines that involve hypothesizing, observation, testing, and evidence. It is an ever-changing and fluid field because regardless of the results of research or experimentation, there will always be more questions to ask. Some examples of scientific fields are biology, botany, psychology, chemistry, astronomy, and physics.

This book deals with the physical sciences—physics and chemistry. All the sciences are based in the use of experiment and testing to understand the world around us better. The scientific method requires us to constantly reexamine our understanding by testing new evidence with our current theories and making changes to those theories if the evidence does not meet the test. The scientific method therefore is a powerful tool you will use throughout the physical sciences.

In this chapter you will learn how to gather evidence using the scientific method. These skills will then be used throughout this textbook to test scientific theories and practices.

Development of a Scientific Theory

The most important, and most exciting, thing about science and scientific theories is that they are not fixed. Hypotheses are formed and carefully tested, leading to scientific theories that explain those observations and predict results. The results are not made to fit the hypotheses. If new information comes to light with the use of better equipment, or the results of other experiments, this new information is used to improve and expand current theories. If a theory is found to have been inaccurate, it is changed to fit this new information. The data should never be made to fit the theory’ if the data does not fit the theory then the theory is reworked or discarded. Although this changing of opinion is often taken for inconsistency, it is this very willingness to adapt that makes science useful, and allows new discoveries to be made.

Remember that the term theory has a different meaning in science. A scientific theory is not like your theory about why you can only ever find one sock. A scientific theory is one that has been tested and proven through repeated experiment and data. Scientists are constantly testing the data available, as well as commonly held beliefs, and it is this constant testing that allows progress and improved theories.

Gravity

The theory of gravity has been slowly developing since the beginning of the 16th century. Galileo Galilei is credited with some of the earliest work. At the time it was widely believed that heavier objects accelerated faster toward the earth than light objects did. Galileo had a hypothesis that this was not true and performed experiments to prove this.

Galileo’s work allowed Sir Isaac Newton to hypothesize not only a theory of gravity on Earth, but that gravity is what held the planets in their orbits. Newton’s theory was used by John Couch Adams and Urbain Le Verrier to predict the planet Neptune in the solar system and this prediction was proved experimentally when Neptune was discovered by Johann Gottfried Galle.

Although a large majority of gravitational motion could be explained by Newton’s theory of gravity, there were things that did not fit. But although a newer theory that better fit the facts was eventually proven by Albert Einstein, Newton’s gravitational theory is still successfully used in many applications where the masses, speeds, and energies are not too large.

Thermodynamics

The principles of the three rules of thermodynamics describe how energy works, on all size levels (from the workings of the Earth’s core, to a car engine). The basis for these three rules started as far back as 1650 with Otto von Guericke. He had a hypothesis that a vacuum pump could be made, and proved this by making one. In 1656 Robert Boyle and Robert Hooke used this information and built an air pump.

Boyle’s law came about from his air pump experiments, where he discovered that pressure is inversely proportional to volume at a constant temperature (p∝1V∝1V at constant T).

Over the next hundreds of years the theory was expanded on and improved. Denis Papin built a steam pressurizer and release valve, and designed a piston cylinder and engine, which Thomas Savery and Thomas Newcomen built. These engines inspired the study of heat capacity and latent heat. Joseph Black and James Watt increased the steam engine’s efficiency and it was their work that Sadi Carnot (considered the father of thermodynamics) studied before publishing a discourse on heat, power, energy, and engine efficiency in 1824.

This work by Carnot was the beginning of modern thermodynamics as a science, with the first thermodynamics textbook written in 1859, and the first and second laws of thermodynamics being determined in the 1850s. Scientists such as Lord Kelvin, Max Planck, and J. Willard Gibbs among many others studied thermodynamics. Over the course of 350 years thermodynamics has developed from the building of a vacuum pump to some of the most important fundamental laws of energy.

Scientific Method

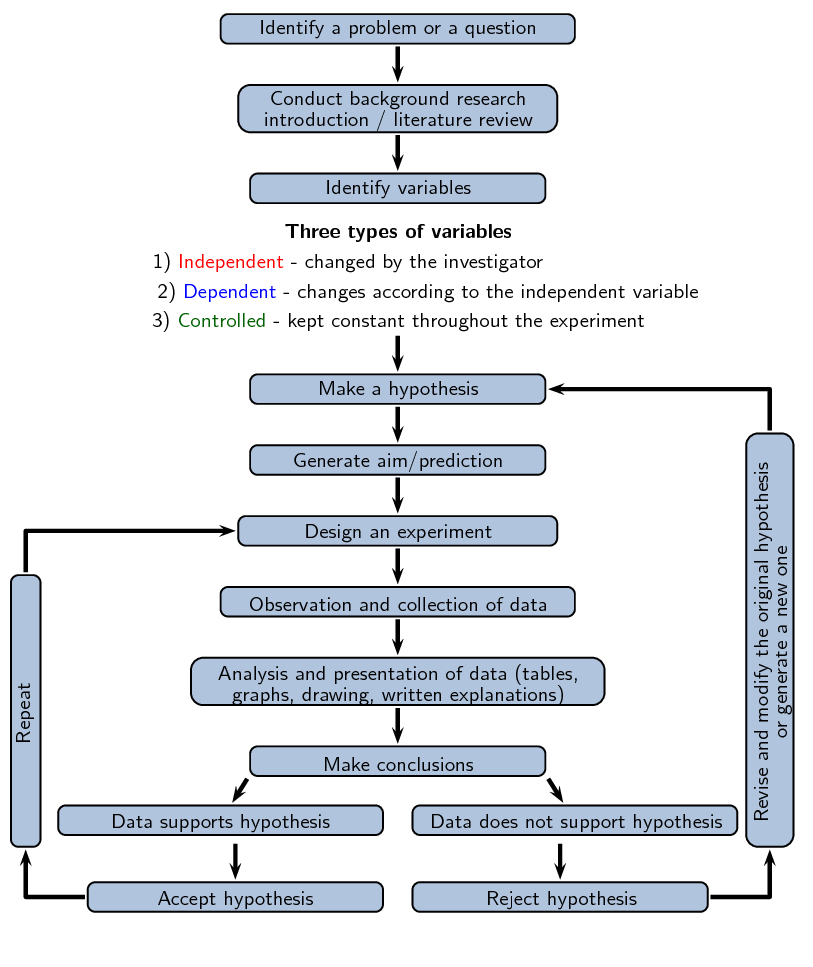

The scientific method is the basic skill process in the world of science. Since the beginning of time humans have been curious as to why and how things happen in the world around us. The scientific method provides scientists with a well-structured scientific platform to help find the answers to their questions. Using the scientific method there is no limit as to what we can investigate. The scientific method can be summarized as follows:

- Ask a question about the world around you.

- Do background research on your questions.

- Make a hypothesis about the event that gives a sensible result. You must be able to test your hypothesis through experiment.

- Design an experiment to test the hypothesis. These methods must be repeatable and follow a logical approach.

- Collect data accurately and interpret the data. You must be able to take measurements, collect information, and present your data in a useful format (drawings, explanations, tables, and graphs).

- Draw conclusions from the results of the experiment. Your observations must be made objectively; never force the data to fit your hypothesis.

- Decide whether your hypothesis explains the data collected accurately.

- If the data fits your hypothesis, verify your results by repeating the experiment or getting someone else to repeat the experiment.

- If your data does not fit your hypothesis, perform more background research and make a new hypothesis.

Remember that in the development of both the gravitational theory and thermodynamics, scientists expanded on information from their predecessors or peers when developing their own theories. It is therefore very important to communicate findings to the public in the form of scientific publications, at conferences, or in articles and TV or radio programs. It is important to present your experimental data in a specific format so that others can read your work, understand it, and repeat the experiment.

- Aim: A brief sentence describing the purpose of the experiment.

- Apparatus: A list of the apparatus.

- Method: A list of the steps followed to carry out the experiment.

- Results: Tables, graphs, and observations about the experiment.

- Discussion: What your results mean.

- Conclusion: A brief sentence about whether the aim was met.

Hypothesis

A hypothesis should be specific and should relate directly to the question you are asking. For example, if your question about the world was Why do rainbows form, your hypothesis could be: Rainbows form (dependent variable) because of light shining through water droplets (independent variable). After formulating a hypothesis, it needs to be tested through experiment under controlled conditions. Controls are kept constant throughout an experiment and provide a constant standard of comparison.

A clear pattern of correlation between the dependent and independent variables must be established. An incorrect prediction does not mean that you have failed. It means that the experiment has brought some new facts to light that you might not have thought of before.

In science we never “prove” a hypothesis through a single experiment because there is a chance that you made an error somewhere along the way. What you can say is that your results support the original hypothesis.

Analysis of the Scientific Method

Study the flow diagram provided, then discuss the questions that follow.

- Once you have a problem you would like to study, why is it important to conduct background research before doing anything else?

- What are the differences between dependent, independent, and controlled variables, and why is it important to identify them?

- What is the purpose of a control in an experiment?

- What is the difference between identifying a problem, a hypothesis, and a scientific theory?

- Why is it important to repeat your experiment if the data fits the hypothesis?

Introduction to Measurements

Measurements provide much of the information that informs the hypotheses, theories, and laws describing the behavior of matter and energy in both the macroscopic and microscopic domains of chemistry. Every measurement provides three kinds of information: the size or magnitude of the measurement (a number), a standard of comparison for the measurement (a unit), and an indication of the uncertainty of the measurement. While the number and unit are explicitly represented when a quantity is written, the uncertainty is an aspect of the measurement result that is more implicitly represented and will be discussed later.

The number in the measurement can be represented in different ways, including decimal form and scientific notation. (Scientific notation is also known as exponential notation; a review of this topic can be found through this link here: Exponential notation review and examples.) For example, the maximum takeoff weight of a Boeing 777-200ER airliner is 298,000 kilograms, which can also be written as 2.98 × 105 kg. The mass of the average mosquito is about 0.0000025 kilograms, which can be written as 2.5 × 10−6 kg.

Units, such as liters, pounds, and centimeters, are standards of comparison for measurements. A 2-liter bottle of a soft drink contains a volume of beverage that is twice that of the accepted volume of 1 liter. The meat used to prepare a 0.25-pound hamburger weighs one-fourth as much as the accepted weight of 1 pound. Without units a number can be meaningless, confusing, or possibly life threatening. Suppose a doctor prescribes phenobarbital to control a patient’s seizures and states a dosage of “100” without specifying units. Not only will this be confusing to the medical professional giving the dose, but the consequences can be dire: 100 mg given three times per day can be effective as an anticonvulsant, but a single dose of 100 g is more than 10 times the lethal amount.

The measurement units for seven fundamental properties (“base units”) are listed in Table 1.1. The standards for these units are fixed by international agreement, and they are called the International System of Units or SI units (from the French, Le Système International d’Unités). SI units have been used by the United States National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) since 1964. Units for other properties may be derived from these seven base units.

|

Base Units of the SI System |

||

|

Property Measured |

Name of Unit |

Symbol of Unit |

|

length |

meter |

m |

|

mass |

kilogram |

kg |

|

time |

second |

s |

|

temperature |

kelvin |

K |

|

electric current |

ampere |

A |

|

amount of substance |

mole |

mol |

|

luminous intensity |

candela |

cd |

Table 1.1

Everyday measurement units are often defined as fractions or multiples of other units. Milk is commonly packaged in containers of 1 gallon (4 quarts), 1 quart (0.25 gallon), and one pint (0.5 quart). This same approach is used with SI units, but these fractions or multiples are always powers of 10. Fractional or multiple SI units are named using a prefix and the name of the base unit. For example, a length of 1,000 meters is also called a kilometer because the prefix kilo means “one thousand,” which in scientific notation is 103 (1 kilometer = 1000 m = 103 m). The prefixes used and the powers to which 10 are raised are listed in Table 1.2.

|

Common Unit Prefixes |

|||

|

Prefix |

Symbol |

Factor |

|

|

femto |

f |

10−15 |

|

|

pico |

p |

10−12 |

|

|

nano |

n |

10−9 |

|

|

micro |

µ |

10−6 |

|

|

milli |

m |

10−3 |

|

|

centi |

c |

10−2 |

|

|

deci |

d |

10−1 |

|

|

kilo |

k |

103 |

|

|

mega |

M |

106 |

|

|

giga |

G |

109 |

|

|

tera |

T |

1012 |

|

Table 1.2

SI Base Units

The initial units of the metric system, which eventually evolved into the SI system, were established in France during the French Revolution. The original standards for the meter and the kilogram were adopted there in 1799 and eventually by other countries. SI stands for Système International, which means “international system” in French. This section introduces four of the SI base units commonly used in chemistry. Other SI units will be introduced in subsequent chapters.

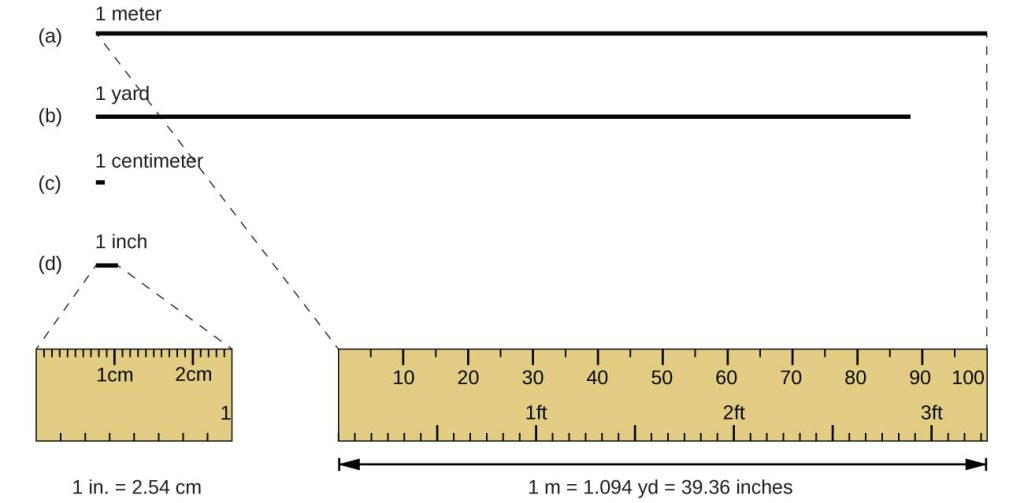

Length

The standard unit of length in both the SI and original metric systems is the meter (m). A meter was originally specified as 1/10,000,000 of the distance from the North Pole to the equator. It is now defined as the distance light in a vacuum travels in 1/299,792,458 of a second. A meter is about 3 inches longer than a yard (Figure 1.3); one meter is about 39.37 inches, or 1.094 yards. Longer distances are often reported in kilometers (1 km = 1000 m = 103 m), whereas shorter distances can be reported in centimeters (1 cm = 0.01 m = 10−2 m) or millimeters (1 mm = 0.001 m = 10−3 m).

Mass

The standard unit of mass in the SI system is the kilogram (kg). The kilogram was previously defined by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) as the mass of a specific reference object. This object was originally one liter of pure water, and more recently it was a metal cylinder made from a platinum-iridium alloy with a height and diameter of 39 mm (Figure 1.4). In May 2019, this definition was changed to one that is based instead on precisely measured values of several fundamental physical constants. One kilogram is about 2.2 pounds. The gram (g) is exactly equal to 1/1000 of the mass of the kilogram (10−3 kg).

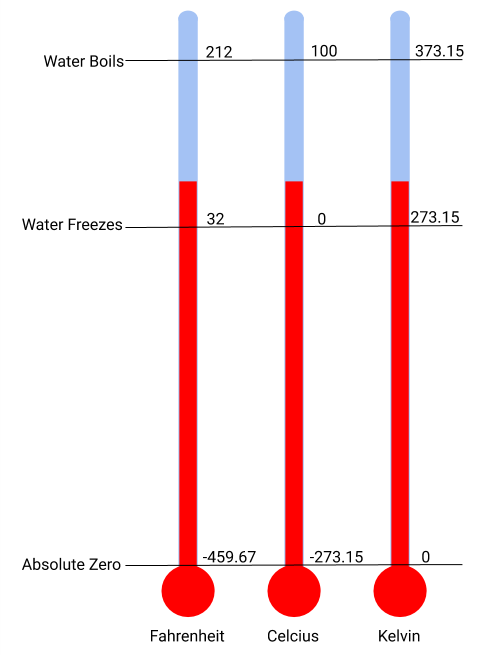

Temperature

The SI unit of temperature is the kelvin (K). The IUPAC convention is to use kelvin (all lowercase) for the word, K (uppercase) for the unit symbol, and neither the word “degree” nor the degree symbol (°). The degree Celsius (°C) is also allowed in the SI system, with both the word “degree” and the degree symbol used for Celsius measurements. Celsius degrees are the same magnitude as those of kelvin, but the two scales place their zeros in different places (Figure 1.5). Water freezes at 273.15 K (0 °C) and boils at 373.15 K (100 °C) by definition, and normal human body temperature is approximately 310 K (37 °C). Kelvin is used by scientists to better reflect the amount of thermal energy in any measurement, with the absence of energy being 0 K (−273.15 °C), also known as absolute zero. The conversion between these two units and the Fahrenheit scale will be discussed later in this chapter.

Time

The SI base unit of time is the second (s). Small and large time intervals can be expressed with the appropriate prefixes: for example, 3 microseconds = 0.000003 s = 3 × 10−6 and 5 megaseconds = 5,000,000 s = 5 × 106 s. Alternatively, hours, days, and years can be used.

Derived SI Units

We can derive many units from the seven SI base units. For example, we can multiply the base unit of length (m) by itself three times to define a unit of volume, m3. We can also use the base units of mass (kg) and length (m) to define a unit of density, which is mass over volume or kg/m3.

Volume

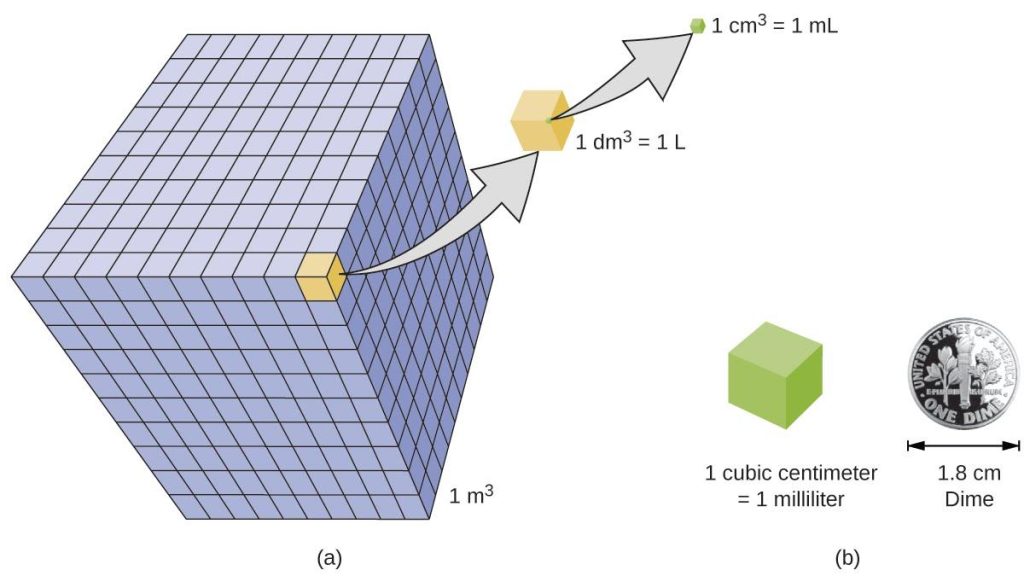

Volume is the measure of the amount of space occupied by an object. The standard SI unit of volume is defined by the base unit of length (Figure 1.6). The standard volume is a cubic meter (m3), a cube with an edge length of exactly one meter. To dispense a cubic meter of water, we could build a cubic box with edge lengths of exactly one meter. This box would hold a cubic meter of water or any other substance.

A more commonly used unit of volume is derived from the decimeter (0.1 m, or 10 cm). A cube with edge lengths of exactly one decimeter contains a volume of one cubic decimeter (dm3). A liter (L) is the more common name for the cubic decimeter. One liter is about 1.06 quarts.

A cubic centimeter (cm3) is the volume of a cube with an edge length of exactly one centimeter. The abbreviation cc (for cubic centimeter) is often used by health professionals. A cubic centimeter is equivalent to a milliliter (mL) and is 1/1000 of a liter.

Density

We use the mass and volume of a substance to determine its density. Thus, the units of density are defined by the base units of mass and length.

The density of a substance is the ratio of the mass of a sample of the substance to its volume. The SI unit for density is the kilogram per cubic meter (kg/m3). For many situations, however, this is an inconvenient unit, and we often use grams per cubic centimeter (g/cm3) for the densities of solids and liquids, and grams per liter (g/L) for gases (at 25 °C and 1 atmospheric pressure [atm]). Although there are exceptions, most liquids and solids have densities that range from about 0.7 g/cm3 (the density of gasoline) to 19 g/cm3 (the density of gold). The density of air is about 1.2 g/L. Table 1.3 shows the densities of some common substances.

|

Densities of Common Substances |

||

|

Solids |

Liquids |

Gases (at 25 °C and 1 atm) |

|

ice (at 0 °C) 0.92 g/cm3 |

water 1.0 g/cm3 |

dry air 1.20 g/L |

|

oak (wood) 0.60–0.90 g/cm3 |

ethanol 0.79 g/cm3 |

oxygen 1.31 g/L |

|

iron 7.9 g/cm3 |

acetone 0.79 g/cm3 |

nitrogen 1.14 g/L |

|

copper 9.0 g/cm3 |

glycerin 1.26 g/cm3 |

carbon dioxide 1.80 g/L |

|

lead 11.3 g/cm3 |

olive oil 0.92 g/cm3 |

helium 0.16 g/L |

|

silver 10.5 g/cm3 |

gasoline 0.70–0.77 g/cm3 |

neon 0.83 g/L |

|

gold 19.3 g/cm3 |

mercury 13.6 g/cm3 |

radon 9.1 g/L |

Table 1.3

While there are many ways to determine the density of an object, perhaps the most straightforward method involves separately finding the mass and volume of the object, and then dividing the mass of the sample by its volume. In the following example, the mass is found directly by weighing, but the volume is found indirectly through length measurements.

Accuracy and Precision

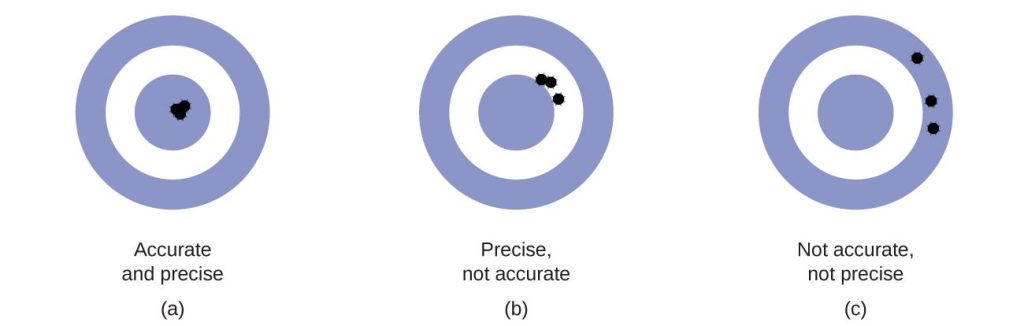

Scientists typically make repeated measurements of a quantity to ensure the quality of their findings and to evaluate both the precision and the accuracy of their results. Measurements are said to be precise if they yield very similar results when repeated in the same manner. A measurement is considered accurate if it yields a result that is very close to the true or accepted value. Precise values agree with each other; accurate values agree with a true value. These characterizations can be extended to other contexts, such as the results of an archery competition (Figure 1.7).

Unit Conversion

It is often the case that a quantity of interest may not be easy (or even possible) to measure directly but instead must be calculated from other directly measured properties and appropriate mathematical relationships. For example, consider measuring the average speed of an athlete running sprints. This is typically accomplished by measuring the time required for the athlete to run from the starting line to the finish line, and the distance between these two lines, and then computing speed from the equation that relates these three properties: speed = distance/time.

An Olympic-quality sprinter can run 100 m in approximately 10 s, corresponding to an average speed of 100 m/10 s = 10 m/s.

Note that this simple arithmetic involves dividing the numbers of each measured quantity to yield the number of the computed quantity (100/10 = 10) and also dividing the units of each measured quantity to yield the unit of the computed quantity (meter divided by second = meter per second). Now, consider using this same relation to predict the time required for a person running at this speed to travel a distance of 25 m. The same relation among the three properties is used, but in this case, the two quantities provided are a speed (10 m/s) and a distance (25 m). To yield the sought property, time, the equation must be rearranged appropriately: time = distance/speed.

The time can then be computed as: 25 m/(10 m/s) = 2.5 s.

Again, arithmetic on the numbers (25/10 = 2.5) was accompanied by the same arithmetic on the units (m/(m/s) = s) to yield the number and unit of the result, 2.5 s. Note that, just as for numbers, when a unit is divided by an identical unit (in this case, m/m), the result is 1—or, as commonly phrased, the units “cancel.”

These calculations are examples of a versatile mathematical approach known as dimensional analysis (or the factor-label method). Dimensional analysis is based on this premise: the units of quantities must be subjected to the same mathematical operations as their associated numbers. This method can be applied to computations ranging from simple unit conversions to more complex, multi-step calculations involving several different quantities.

Conversion Factors and Dimensional Analysis

A ratio of two equivalent quantities expressed with different measurement units can be used as a unit conversion factor. For example, the lengths of 2.54 cm and 1 in. are equivalent (by definition), and so a unit conversion factor may be derived from the ratio 2.54 cm/1 in., (2.54 cm = 1 in.), or 2.54 cm/in.

Several other commonly used conversion factors are given in Table 1.4.

|

Common Conversion Factors |

||

|

Length |

Volume |

Mass |

|

1 m = 1.0936 yd |

1 L = 1.0567 qt |

1 kg = 2.2046 lb |

|

1 in. = 2.54 cm (exact) |

1 qt = 0.94635 L |

1 lb = 453.59 g |

|

1 km = 0.62137 mi |

1 ft3 = 28.317 L |

1 (avoirdupois) oz = 28.349 g |

|

1 mi = 1609.3 m |

1 tbsp = 14.787 mL |

1 (troy) oz = 31.103 g |

Table 1.4

When a quantity (such as distance in inches) is multiplied by an appropriate unit conversion factor, the quantity is converted to an equivalent value with different units (such as distance in centimeters). For example, a basketball player’s vertical jump of 34 inches can be converted to centimeters with 34 in. × (2.54 cm/1 in.) = 86 cm.

Since this simple arithmetic involves quantities, the premise of dimensional analysis requires that we multiply both numbers and units. The numbers of these two quantities are multiplied to yield the number of the product quantity, 86, whereas the units are multiplied to yield in. × (cm/in.) Just as for numbers, a ratio of identical units is also numerically equal to one, in./in. = 1, and the unit product thus simplifies to cm. (When identical units divide to yield a factor of 1, they are said to “cancel.”) Dimensional analysis may be used to confirm the proper application of unit conversion factors as demonstrated in the following example.

Beyond simple unit conversions, the factor-label method can be used to solve more complex problems involving computations. Regardless of the details, the basic approach is the same—all the factors involved in the calculation must be appropriately oriented to ensure that their labels (units) will appropriately cancel and/or combine to yield the desired unit in the result. As your study of chemistry continues, you will encounter many opportunities to apply this approach.

Example 1.1

CONVERTING GRAMS TO OUNCES

The mass of a competition frisbee is 125 g. Convert its mass to ounces using the unit conversion factor derived from the relationship 1 oz. = 28.349 g.

Solution

Given the conversion factor, the mass in ounces may be derived using an equation similar to the one used for converting length from inches to centimeters.

x oz. = 125 g × unit conversion factor

The unit conversion factor may be represented as 1 oz./28.349 g and 28.349 g/1 oz.

The correct unit conversion factor is the ratio that cancels the units of grams and leaves ounces.

x oz. = 125g × (1 oz./28.349 g) = 125/28.349 oz. = 4.41 oz.

Example 1.2

CALCULATING FUEL ECONOMY AND FUEL COSTS

While being driven from Philadelphia to Atlanta, a distance of about 1,250 km, a 2014 Lamborghini Aventador Roadster uses 213 L of gasoline.

(a) What (average) fuel economy, in miles per gallon, did the Roadster get during this trip?

(b) If gasoline costs $3.80 per gallon, what was the fuel cost for this trip?

Solution

(a) First convert distance from kilometers to miles:

1250km × (0.62137 mi/1 km) = 777 mi

and then convert volume from liters to gallons:

213 L× (1.0567 qt/1 L) × (1 gal/4 qt) = 56.3 gal

Finally,

(average) mileage = 777 mi/56.3 gal = 13.8 miles/gallon = 13.8 mpg

Alternatively, the calculation could be set up in a way that uses all the conversion factors sequentially, as follows:

(1250 km/213 L) × (0.62137 mi/1 km) × (1 L/1.0567 qt) × (4 qt/1 gal) = 13.8 mpg

(b) Using the previously calculated volume in gallons, we find:

56.3 gal × ($3.80/1 gal) = $214

Check Your Understanding

The content in this chapter is adapted from multiple sources. The overall chapter structure and the section on the nature of science are adapted from Exploring the Physical World and are used under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. The section on scientific method is adapted from Siyavula Physical Sciences Grade 12 textbook and is used under a Creative Commons Attribution-Unported 3.0 International License. The section on measurements is adapted from Chemistry 2e by OpenStax and is used under a Creative Commons-Attribution 4.0 International License.

Media Attributions

- Fig. 1.1 © Unknown Author is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Fig 1.2 © Siyavulu is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Fig. 1.3 © OpenStax is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Fig 1.4 © National Institute of Standards and Technology is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Fig. 1.5 © Nadine Gergel-Hackett is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Fig 1.6 © OpenStax is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Fig. 1.7 © OpenStax is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

a scientific procedure undertaken to make a discovery, test a hypothesis, or demonstrate a known fact

a collection of principles and procedures for the systematic pursuit of knowledge involving the recognition and formulation of a problem, the collection of data through observation and experiment, and the formulation and testing of hypotheses

carefully thought-out explanations for observations of the natural world that have been constructed using the scientific method, and which brings together a myriad of facts and hypotheses

: the collecting and recording of data, which enables scientists to construct and then test hypotheses and theories

a testable statement about the relationship between two or more variables or a proposed explanation for some observed phenomenon

statements, based on repeated experiments or observations, that describe or predict a range of natural phenomena

variable that changes as a result of the independent variable manipulation

variable that stands alone and isn't changed by the other variables you are trying to measure but manipulated by the researcher

standards to which comparisons are made in an experiment

the process of obtaining the magnitude of a quantity relative to an agreed standard

a range of possible values within which the true value of the measurement lies

a way of writing very large or very small numbers

a dimensionless quantity representing the amount of matter in a particle or object

a particular physical quantity, defined and adopted by convention, with which other quantities of the same kind are compared to express their value

the force acting on an object due to gravity

qualities and characteristics of individual substances that describe and identify them

one of a set of simple units in a system of measurement that is based on a natural phenomenon or established standard and from which other units may be derived

a set of base units, derived units, and a set of decimal-based multipliers that are used as prefixes

a letter or series of letters attached to the beginning of a word, word base, or suffix to produce a derivative word with a new meaning

the repeated multiplication of a factor and the number which is raised to that base factor is the exponent

the decimal measuring system based on the meter, liter, and gram as units of length, capacity, and weight or mass

the measurement of the extent of something along its greatest dimension; a measurement of the physical quantity of distance

the base unit of length in the International System of Units (SI)

base unit of mass in the International System of Units (SI)

a measure of the average kinetic energy of the particles in an object

base unit of thermodynamic temperature measurement in the International System of Units (SI). It is represented by the symbol K

temperature scale, also called centigrade, according to which water freezes at zero degrees and boils at one hundred degrees

technically known as zero kelvins, equals −273.15 degrees Celsius, or −459.67 Fahrenheit, and marks the spot on the thermometer where a system reaches its lowest possible energy, or thermal motion

change from one set of units to another, by multiplying or dividing

scale for measuring temperature, in which water freezes at 32 degrees and boils at 212 degrees

quantity of three-dimensional space occupied by a liquid, solid, or gas

mass of a unit volume of a material substance

closeness of two or more measurements to each other

closeness of a measured value to a standard or known value

process that uses conversion factors to convert from one set of units to another