3 The Bronze Age and the Iron Age

The Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a term used to describe a period in the ancient world from about 3000 BCE to 1100 BCE. That period saw the emergence and evolution of increasingly sophisticated ancient states, some of which evolved into real empires. It was a period in which long-distance trade networks and diplomatic exchanges between states became permanent aspects of political, economic, and cultural life in the eastern Mediterranean region. It was, in short, the period during which civilization itself spread and prospered across the area.

The period is named after one of its key technological bases: the crafting of bronze. Bronze is an alloy of tin and copper. An alloy is a combination of metals created when the metals bond at the molecular level to create a new material entirely. Needless to say, historical peoples had no idea why, when they took tin and copper, heated them up, and beat them together on an anvil they created something much harder and more durable than either of their starting metals. But some innovative smith did figure it out, and in the process ushered in an array of new possibilities.

The Bronze Age States

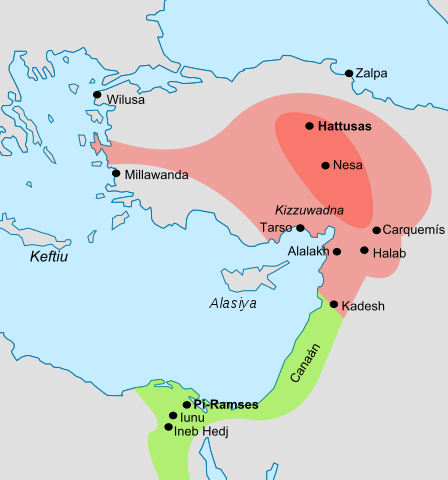

There were four major regions along the shores of, or near to, the eastern Mediterranean that hosted the major states of the Bronze Age: Greece, Anatolia, Canaan and Mesopotamia, and Egypt. Those regions were close enough to one another (e.g., it is roughly 800 miles from Greece to Mesopotamia, the furthest distance between any of the regions) that ongoing long-distance trade was possible. While wars were relatively frequent, most interactions between the states and cultures of the time were peaceful, revolving around trade and diplomacy. Each state, large and small, oversaw diplomatic exchanges written in Akkadian (the international language of the time) maintaining relations, offering gifts, and demanding concessions as circumstances dictated. Although the details are often difficult to establish, we can assume that at least some immigration occurred as well.

One state whose very existence coincided with the Bronze Age, vanishing afterward, was that of the Hittites. The Hittites were the quintessential Bronze Age civilization: militarily powerful, economically prosperous, and connected through diplomacy and war with the other cultures and states of the time. Beginning in approximately 1700 BCE, the Hittites established a large empire in Anatolia, the landmass that comprises present-day Turkey. The Hittite Empire expanded rapidly based on a flourishing bronze-age economy, expanding from Anatolia to conquer territory in Mesopotamia, Syria, and Canaan, ultimately clashing with the New Kingdom of Egypt. The Hittites had the practice of adopting the customs, technologies, and religions of the people they conquered and the people they came in contact with. They did not seek to impose their own customs on others, instead gathering the literature, stories, and beliefs of their subjects. Their pantheon of gods grew every time they conquered a new city-state or tribe, and they translated various tales and legends into their own language. There is some evidence that it was the Hittites who formed the crucial link between the civilizations of Mesopotamia and the civilizations of the Mediterranean – most importantly, of the Greeks.

To the east of the Hittite Empire, Mesopotamia was not ruled by a single state or empire during most of the Bronze Age. The Babylonian empire founded by Hammurabi was invaded by the Hittites, who sacked Babylon but did not stay to rule over it. Instead, Babylon was ruled by the Kassites (whose origins are unknown) beginning in 1595 BCE. Over the following centuries, the Kassites successfully ruled over Babylon and the surrounding territories, with the entire region enjoying a period of prosperity. To the north, beyond Mesopotamia (the land between the rivers) itself, a rival state known as Assyria both traded with and warred against Kassite-controlled Babylon. Eventually (starting in 1225 BCE), Assyria led a short-lived period of conquest where it conquered Babylon and the Kassites, going on to rule over a united Mesopotamia before being forced to retreat against the backdrop of a wider collapse of the political and commercial network of the Bronze Age.

To the west, it was during the Bronze Age that the first distinctly Greek civilizations arose: the Minoans of the island of Crete and the Mycenaeans of Greece itself. Their civilizations, which likely merged together due to invasion after a long period of coexistence, were the basis of later Greek civilization and thus a profound influence on many of the neighboring civilizations of the Middle East in the centuries to come, just as the civilizations of the Middle East unquestionably influenced them. Both the Minoans and Mycenaeans were seafarers.

The Minoans built enormous palace complexes that combined government, spiritual, and commercial centers in huge, sprawling buildings that were interconnected and which housed thousands of people. The Greek legend of the labyrinth, the great maze in which a bull-headed monster called the minotaur roamed, was probably based on the size and the confusion of these Minoan complexes. Frescoes painted on the walls of the palaces depicted elaborate athletic events featuring naked men leaping over charging bulls. Minoan frescoes have even been found in the ruins of an Egyptian (New Kingdom) palace, indicating that Minoan art was valued outside of Crete itself.

The Minoans traded actively with their neighbors and developed their own systems of bureaucracy and writing. They used a form of writing referred to by historians as Linear A, which has never been deciphered. Their civilization was very rich and powerful by about 1700 BCE and it continued to prosper for centuries. Starting in the early 1400s BCE, however, a wave of invasions carried out by the Mycenaeans to the north eventually extinguished Minoan independence. By that time, the Minoans had already shared artistic techniques, trade, and their writing system with the Mycenaeans, the latter of which served as the basis of Mycenaean record keeping in a form referred to as Linear B. Thus, while the Minoans lost their political independence, Bronze-Age Greek culture as a whole became a blend of Minoan and Mycenaean influences.

Centuries later, the culture of the Mycenaeans would be celebrated in the epic poems (nominally written by the poet Homer, although it is likely “Homer” is a mythical figure himself) the Iliad and the Odyssey, describing the exploits of great Mycenaean heroes like Agamemnon, Achilles, and Odysseus. Those exploits almost always revolved around warfare, as immortalized in Homer’s account of the Mycenaean siege of Troy, a city in western Anatolia whose ruins were discovered in the late nineteenth century CE.

The Mycenaeans relied on the sea so heavily because Greece was a very difficult place to live. Unlike Egypt or Mesopotamia, there were no great rivers feeding fertile soil, just mountains, hills, and scrubland with poor, rocky soil. There were few mineral deposits or other natural resources that could be used or traded with other lands. As it happens, there are iron deposits in Greece, but its use was not yet known by the Mycenaeans. They thus learned to cultivate olives to make olive oil and grapes to make wine, two products in great demand all over the ancient world that were profitable enough to sustain seagoing trade. It is also likely that the difficult conditions in Greece helped lead the Mycenaeans to be so warlike, as they raided each other and their neighbors in search of greater wealth and opportunity.

The Mycenaeans were a society that glorified noble warfare. As war is depicted in the Iliad, battles consisted of the elite noble warriors of each side squaring off against each other and fighting one-on-one, with the rank-and-file of poorer soldiers providing support but usually not engaging in actual combat. In turn, Mycenaean ruins (and tombs) make it abundantly clear that most Mycenaeans were dirt-poor farmers working with primitive tools, lorded over by bronze-wielding lords who demanded labor and wealth. Foreign trade was in service to providing luxury goods to this elite social class, a class that was never politically united but instead shared a common culture of warrior-kings and their armed retinues. Some beautiful artifacts and amazing myths and poems have survived from this civilization, but it was also one of the most predatory civilizations we know about from ancient history.

The Collapse of the Bronze Age

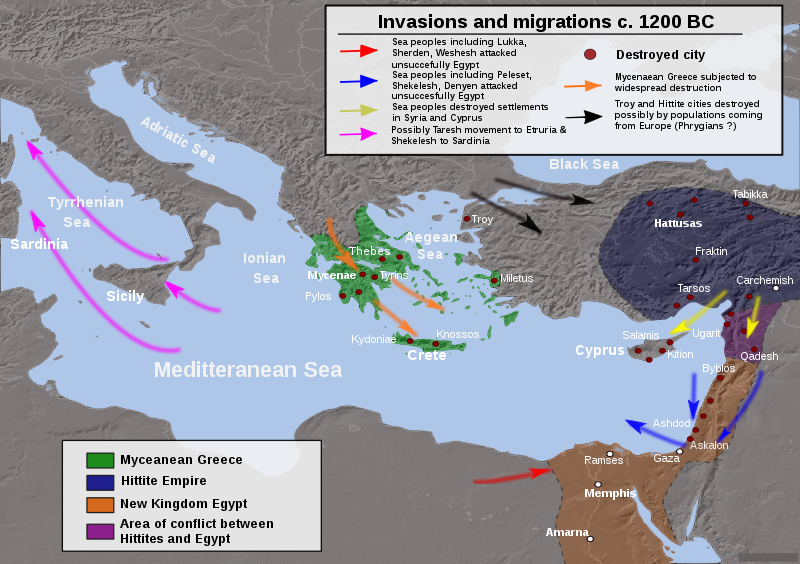

The Bronze Age at its height witnessed several large empires and peoples in regular contact with one another through both trade and war. The pharaohs of the New Kingdom corresponded with the kings and queens of the Hittite Empire and the rulers of the Kassites and Assyrians; it was normal for rulers to refer to one another as “brother” or “sister.” Each empire warred with its rivals at times, but it also worked with them to protect trade routes. Certain Mesopotamian languages, especially Akkadian, became international languages of diplomacy, allowing travelers and merchants to communicate wherever they went. Even the warlike and relatively unsophisticated Mycenaeans played a role on the periphery of this ongoing network of exchange.

That said, most of the states involved in this network fell into ruin between 1200 and 1100 BCE. The great empires collapsed, followed by a period of about 100 years of recovery, with new empires arising in the aftermath. There is still no definitive explanation for why this collapse occurred, not least because the states that had been keeping records stopped doing so as their bureaucracies disintegrated. The surviving evidence seems to indicate that some combination of events – some caused by humans and some environmental – probably worked in tandem to spell the end of the Bronze Age.

Around 1050 BCE, two of the victims of the collapse, the New Kingdom of Egypt and the Hittite Empire, left clear indications in their records that drought had undermined their grain stores and their social stability. In recent years archaeologists have presented strong scientific evidence that the climate of the entire region became warmer and more arid, supporting the idea of a series of debilitating droughts. Even the greatest of the Bronze Age empires existed in a state of relative precarity, relying on regular harvests in order to not just feed their population, but sustain the governments, armies, and building projects of their states as a whole. Thus, environmental disaster could have played a key role in undermining the political stability of whole regions at the time.

For roughly 100 years, from 1200 BCE to 1100 BCE, the networks of trade and diplomacy considered above were either disrupted or destroyed completely. Egypt recovered and new dynasties of pharaohs were sometimes able to recapture some of the glory of the past Egyptian kingdoms in their building projects and the power of their armies, but in the long run Egypt proved vulnerable to foreign invasion from that point on. Mycenaean civilization collapsed utterly, leading to a Greek “dark age” that lasted some three centuries. The Hittite Empire never recovered in Anatolia, while in Mesopotamia the most noteworthy survivor of the collapse – the Assyrian state – went on to become the greatest power the region had yet seen.

The Iron Age

The decline of the Bronze Age led to the beginning of the Iron Age. Without copper and tin available, some innovative smiths figured out that it was possible, through a complicated process of forging, to create iron implements that were hard and durable. Iron was available in various places throughout the Middle East and Mediterranean regions, so it did not require long-distance trade, as bronze had. The Iron Age thus began around 1100 BCE, right as the Bronze Age ended.

Outside of Greece, which suffered its long “dark age” following the collapse of the Bronze Age, a number of prosperous societies and states emerged relatively quickly at the start of the Iron Age. They re-established trade routes and initiated a new phase of Middle Eastern politics that eventually led to the largest empires the world had yet seen.

Iron Age Cultures and States

The region of Canaan, which corresponds with modern Palestine, Israel, and Lebanon, had long been a site of prosperity and innovation. Merchants from Canaan traded throughout the Middle East, its craftsmen were renowned for their work, and it was even a group of Canaanites – the Hyksos – who briefly ruled Egypt during the Second Intermediate Period. Along with their neighbors the Hebrews, the most significant of the ancient Canaanites were the Phoenicians, whose cities (politically independent but united in culture and language) were centered in present-day Lebanon.

The Phoenicians were not a particularly warlike people. Instead, they are remembered for being travelers, particularly by sea, and merchants. They traveled farther than any other ancient people; sometime around 600 BCE, according to the Greek historian Herodotus, a Phoenician expedition even sailed around Africa over the course of three years (if that actually happened, it was an achievement that would not be accomplished again for almost 2,000 years). The Phoenicians established colonies all over the Mediterranean shores, where they provided anchors in a new international trade network that eventually replaced the one destroyed with the fall of the Bronze Age. The most prominent Phoenician city was Carthage in North Africa, which centuries later would become the great rival of the Roman Republic.

Phoenician trade was not, however, the most important legacy of their society. Instead, none of their various accomplishments has had a more lasting influence than that of their writing system. As early as 1300 BCE, building on the work of earlier Canaanites, the Phoenicians developed a syllabic alphabet that formed the basis of Greek and Roman writing much later. A syllabic alphabet has characters that represent sounds (called phonemes), rather than characters that represent things or concepts. These alphabets are much smaller and less complex than symbolic ones. It is possible for a non-specialist to learn to read and write using a syllabic alphabet much more quickly than using a symbolic one (like Egyptian hieroglyphics or Chinese characters).

Empires of the Iron Age

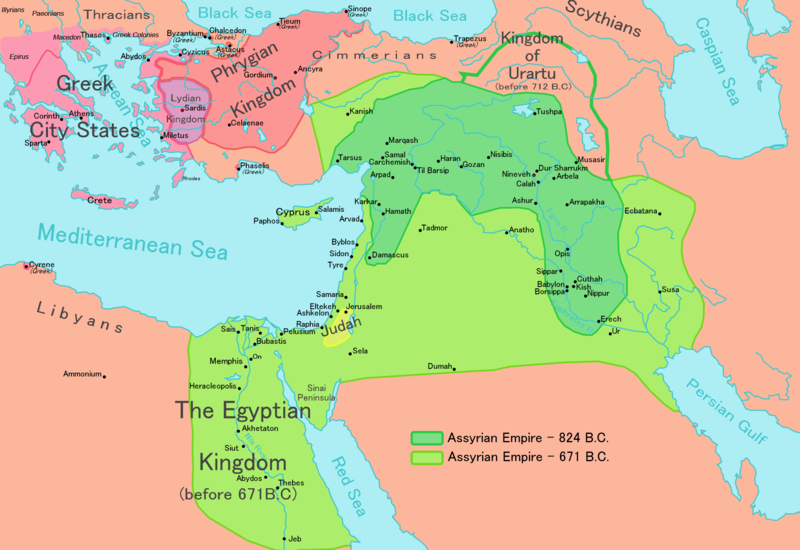

While the Phoenicians played a major role in jumpstarting long-distance trade after the collapse of the Bronze Age, they did not create a strong united state. Such a state emerged farther east, however: alone of the major states of the Bronze Age, the Assyrian kingdom in northern Mesopotamia survived. Probably because of their extreme focus on militarism, the Assyrians were able to hold on to their core cities while the states around them collapsed. During the Iron Age, the Assyrians became the most powerful empire the world had ever seen. The Assyrians were the first empire in world history to systematically conquer almost all of their neighbors using a powerful standing army and go on to control the conquered territory for hundreds of years. They represented the pinnacle of military power and bureaucratic organization of all of the civilizations considered thus far.

Their region in northern Mesopotamia, Ashur, has no natural borders, and thus they needed a strong military to survive; they were constantly forced to fight other civilized peoples from the west and south, and nomads from the north. The Assyrians held that their patron god, a god of war also called Ashur, demanded the subservience of other peoples and their respective gods. Thus, their conquests were justified by their religious beliefs as well as a straightforward desire for dominance.

Over the next century, the (Neo-)Assyrians became the mightiest empire yet seen in the Middle East. They combined terror tactics with various technological and organizational innovations. They would deport whole towns or even small cities when they defied the will of the Assyrian kings, resettling conquered peoples as indentured workers far from their homelands. They tortured and mutilated defeated enemies, even skinning them alive, when faced with any threat of resistance or rebellion. The formerly-independent Phoenician city-states within the Assyrian zone of control surrendered, paid tribute, and deferred to Assyrian officials rather than face their wrath in battle. The Assyrians were the most effective military force of the ancient world up to that point. They outfitted their large armies with well-made iron weapons (they appear to be the first major kingdom to manufacture iron weapons in large numbers). The Assyrians introduced two innovations in military technology and organization that were of critical importance: a permanent cavalry, the first of any state in the world, and a large standing army of trained infantry.

The style of Assyrian rule ensured the hatred of conquered peoples. They demanded constant tribute and taxation and funneled luxury goods back to their main cities. The Assyrians finally fell in 609 BCE, overthrown by a series of rebellions.

The Neo-Babylonians adopted some of the terror tactics of the Assyrians; they, too, deported conquered enemies as servants and slaves. Where they differed, however, was in their focus on trade. They built new roads and canals and encouraged long-distance trade throughout their lands. They were often at war with Egypt, which also tried to take advantage of the fall of the Assyrians to seize new land, but even when the two powers were at war Egyptian merchants were still welcome throughout the Neo-Babylonian empire.

A combination of flourishing trade and high taxes led to huge wealth for the king and court, and among other things led to the construction of noteworthy works of monumental architecture to decorate their capital. The Babylonians inherited the scientific traditions of ancient Mesopotamia, becoming the greatest astronomers and mathematicians yet seen, able to predict eclipses and keep highly detailed calendars. They also created the zodiac used up to the present in astrology, reflecting the age-old practice of both science and “magic” that were united in the minds of Mesopotamians. In the end, however, they were the last of the great ancient Mesopotamian empires that existed independently. Less than 100 years after their successful rebellion against the Assyrians, they were conquered by what became the greatest empire in the ancient world to date: the Persians, described in a following chapter.

The Hebrews

Ancient Hebrew History

Of the Bronze and Iron Age cultures, one played perhaps the most vital role in the history of Western Civilization: the Hebrews. The Hebrews, a people who first created a kingdom in the ancient land of Canaan, were among the most important cultures of the western world, comparable to the ancient Greeks or Romans. Unlike the Greeks and Romans, the ancient Hebrews were not known for being scientists or philosophers or conquerors. It was their religion, Judaism, that proved to be of crucial importance in world history, both for its own sake and for being the religious root of Christianity and Islam. Together, these three religions are referred to as the “Religions of the Book” in Islam, because they share a set of beliefs first written down in the Hebrew holy texts and they all venerate the same God.

The most important source we have about it is the Hebrew Bible itself, which describes in detail the travails of the Hebrews, their enslavement, battles, triumphs, and accomplishments. The problem with using the Hebrew Bible as a historical source is that it is written in a mythic mode – like the literature of every other Iron Age civilization, many events affecting the Hebrews are explained by direct divine intervention rather than a more prosaic historical approach.

According to the Hebrew Bible, the first patriarch (male clan leader) of the Hebrews was Abraham, a man who led the Hebrews away from Mesopotamia in about 1900 BCE. The Hebrews left the Mesopotamian city of Ur and became wandering herders; in fact, the word Hebrew originally meant “wanderer” or “nomad.” Abraham had a son, Isaac, and Isaac had a son, Jacob, collectively known as the Patriarchs in the Hebrew Bible. The Mesopotamian origins of the Hebrews are unclear from sources outside of the Hebrew Bible itself; archaeological evidence indicates that the Hebrews may have actually been from the Levant, with trade contact with the Mesopotamians, rather than coming from Mesopotamia.

According to Jewish belief, by far the most important thing Abraham did was agree to the Covenant, the promise made between the God Yahweh (the “name” of God is derived from the Hebrew characters for the phrase “I am who I am,” the enigmatic response of God when asked for His name by the prophet Moses) and the Hebrews. The Covenant stated that in return for their devotion and worship, and the circumcision of all Hebrew males, the Hebrews would receive from Yahweh a “land of milk and honey,” a place of peace and prosperity of their own for all time.

According to the Hebrew Bible, Moses was not only responsible for leading the Hebrews from Egypt but for modifying the Covenant. In addition to the exclusive worship of Yahweh and the circumcision of all male Hebrews, the Covenant was amended by Yahweh to include specific rules of behavior: the Hebrews had to abide by the 10 Commandments in order for Yahweh to guarantee their prosperity in the promised land. Having agreed to the Commandments, the Hebrews then arrived in the region that was to become their first kingdom, Israel.

As noted above, the tales present in the Hebrew Bible cannot generally be verified with empirical evidence. They also bear the imprint of earlier traditions: many stories in the Hebrew Bible are taken from earlier Mesopotamian legends. The story of Moses is very close to the account of Sargon the Great’s rise from obscurity in Akkadian tradition, and the flood legend (described in the Bible’s first book, Genesis) is taken directly from the Epic of Gilgamesh, although the motivation of the Mesopotamian gods versus that of Yahweh in those two stories is very different: the Mesopotamian gods are cruel and capricious, while the flood of Yahweh is sent as a punishment for the sins of humankind.

The Kings and Kingdoms

Conflicts with the Philistines, another Canaanite people on the coast, led them to appoint a king, Saul, in about 1020 BCE. The Philistines were one of the groups of “Sea People” who had attacked the New Kingdom of Egypt. The Philistines were a small but powerful kingdom. They were armed with iron and they fought the Hebrews to a standstill initially – at one point they captured the Ark of the Covenant, containing the stone tablets on which the Ten Commandments were written. Under the leadership of their kings, however, the Hebrews pushed back the Philistines and eventually defeated them completely.

Saul’s successor was David, one of his former lieutenants, and David’s was his son Solomon, renowned for his wisdom. The Hebrew kings founded a capital at Jerusalem, which had been a Philistine town. The kings created a professional army, a caste of scribes, and a bureaucracy. All of this being noted, the kingdom itself was not particularly large or powerful; Jerusalem at the time was a hill town of about 5,000 people. Israel emerged as one of the many smaller kingdoms surrounded by powerful neighbors, engaging in trade and waging small-scale wars depending on the circumstances.

Solomon was an effective ruler, forming trade relationships with nearby kingdoms and overseeing the growing wealth of Israel. He also lived in a manner consistent with other Iron Age kings, with many wives and a whole harem of concubines as well. Likewise, he taxed both trade passing through the Hebrew kingdom and his own subjects. His demands for free labor from the Hebrew people amounted to one day in every three spent working on palaces and royal building projects – an enormous amount from a contemporary perspective, but one that was at least comparable to the redistributive economies of nearby kingdoms. Thus, while his subjects came to resent aspects of his rule, it was not markedly more exploitative than the norm in the region as a whole.

The most important building project under Solomon was the great Temple of Jerusalem, the center of the Yahwist religion. There, a class of priests carried out rituals and worship of Yahweh. Members of the religion believed that God’s attention was centered on the Temple. Likewise, the rituals were similar to those practiced among various Middle Eastern religions, focusing on the sacrifice and burning of animals as offerings to God. David and Solomon supported the priesthood, and there was thus a direct link between the growing Yahwist faith and the political structure of Israel.

The kingdom itself was fairly rich, thanks to its good spot on trade routes and the existence of gold mines, but Solomon’s ongoing taxation and labor demands were such that resentment developed among the Hebrews over time. After his death, ten out of the twelve tribes broke off to form their own kingdom, retaining the name Israel, while the smaller remnant of the kingdom took on the name Judah.

In Judah, there were two prevailing patterns: vassalage and rebellion. Judah was simply too small to avoid paying tribute to various neighboring powers, but its people were proud and defensive of their independence, so every generation or so there were uprisings. The worst case was in 586 BCE, when the Jews rose up against the Neo-Babylonian Empire that succeeded the Assyrians. The Babylonians burned Jerusalem, along with Solomon’s Temple, to the ground, and they enslaved tens of thousands of Jews. The Jews were deported to Babylon, just as the Israelites had been deported to Assyrian territory about 150 years earlier – this event is referred to as the “Babylonian Captivity” of the Jews.

Two generations later, when the Neo-Babylonian empire itself fell to the Persians, the Persian emperor Cyrus the Great allowed all of the enslaved people of the Babylonians to return to their homelands, so the Babylonian Captivity came to an end and the Jews returned to Judah, where they rebuilt the Temple. That being noted, what is referred to as the Jewish “diaspora,” meaning the geographical dispersion of the Jews, really began in 538 BCE, because many Jews chose to remain in Babylon and, soon, other cities in the Persian Empire. Since they continued to practice Judaism and carry on Jewish traditions, the notion of a people scattered across different lands but still united by culture and religion came into being.

After being freed by Cyrus, the Jews were still part of the Persian Empire, ruled by a Persian governor (called a “satrap”). For most of the rest of their history, the Jews were able to maintain their distinct cultural identity and their religion, but rarely their political independence. The Jews went from being ruled by the Persians to the Greeks to the Romans (although they did occasionally seize independence for a time) and were then eventually scattered across the Roman Empire. The real hammer-blow of the Diaspora was in the 130s CE, when the Romans destroyed much of Jerusalem and forced almost all of the Jews into exile – the word diaspora itself means “scattering,” and with the destruction of the Jewish kingdom by Rome there would be no Jewish state again until the foundation of the modern nation of Israel in 1948 CE.

The Yahwist Religion and Judaism

The Hebrew Bible claims that the Jews as a people worshipped Yahweh exclusively from the time of the Covenant, albeit with the worship of “false” gods from neighboring lands sometimes undermining their unity. A more likely scenario is that the Hebrews, like every other culture in the ancient world, worshipped a variety of deities, with Yahweh in a place of particular importance and centrality.

As the Hebrews became more powerful, however, their religion changed dramatically. A tradition of prophets, later remembered as the Prophetic Movement, arose among certain people who sought to represent the poorer and more beleaguered members of the community, calling for a return to the more communal and egalitarian society of the past. The Prophetic Movement claimed that the Hebrews should worship Yahweh exclusively and that Yahweh had a special relationship with the Hebrews that set Him apart as a God and them apart as a people.

This new set of beliefs, regarding the special relationship of a single God to the Hebrews, is referred to historically as the Yahwist religion. It was not yet “Judaism,” since it did not yet disavow the belief that other gods might exist, nor did it include all of the rituals and traditions associated with later Judaism. Initially, most of the Hebrews continued to at least acknowledge the existence of other gods – this phenomenon is called henotheism, the term for the worship of only one god in the context of believing in the existence of more than one god (i.e., many gods exist, but we only worship one of them). Over time, this changed into true monotheism: the belief that there is only one god and that all other “gods” are illusory.

The Prophetic Movement attacked both polytheism and the Yahwist establishment centered on the Temple of Jerusalem. The prophets were hostile to both the political power structure and to deviation from the exclusive worship of Yahweh. This is, so far as historians know, the first instance in world history in which the idea of a single all-powerful deity emerged among any people, anywhere (although some scholars consider Akhenaten’s attempted religious revolution in Egypt a quasi-monotheism). Up to this point, all religions held that there were many gods or spirits and that they had some kind of direct, concrete connections to specific areas. Likewise, the gods in most religions were largely indifferent to the actions of individuals so long as the proper prayers were recited and rituals performed. Ethical conduct did not have much influence on the gods (“ethical conduct” itself, of course, differing greatly from culture to culture); what mattered was that the gods were adequately appeased.

In contrast, early Judaism developed the belief that Yahweh was deeply invested in the actions of His chosen people both as a group and as individuals, regardless of their social station. There are various stories in which Yahweh judged people, even kings like David and Solomon, making it clear that all people were known to Yahweh and no one could escape His judgment. The key difference between this belief and the idea of divine anger in other ancient religions was that Yahweh only punished those who deserved it. He was not capricious and cruel like the Mesopotamian gods, for instance, nor flighty and given to bickering like the Greek gods. The early vision of Yahweh present in the Yahwist faith was of a powerful but not all-powerful being whose authority and power were focused on the Hebrew people and the territory of the Hebrew kingdom only. In other words, the priests of Yahweh did not claim that he ruled over all people, everywhere, only that he was the God of the Hebrews and their land. That started to change when the Assyrians destroyed the northern kingdom of Israel in 722 BCE.

The most important reforms of Hebrew religion occurred in the seventh century BCE. A Judean king, Josiah, insisted on the imposition of strict monotheism and the compilation of the first books of the Hebrew Bible, the Torah, in 621 BCE. The sacred writings compiled during these events were all in the mode of the new monotheism. In these writings, Yahweh had always been there as the exclusive god of the Hebrew people and had promised them a land of abundance and peace (i.e., Israel) in return for their exclusive worship of Him. In these histories, the various defeats of the Hebrew people were explained by corruption from within, often the result of Hebrews straying from the Covenant and worshiping other gods.

These reforms were complete when the Neo-Babylonians conquered Judah in 586 BCE and enslaved tens of thousands of the Hebrews. The impact of this event was enormous, because it led to the belief that Yahweh could not be bound to a single place. He was no longer just the god of a single people in a single land, worshiped at a single temple, but instead became a boundless God, omnipotent and omnipresent. The special relationship between Him and the Hebrews remained, as did the promise of a kingdom of peace, but the Hebrews now held that He was available to them wherever they went and no matter what happened to them.

In Babylon itself, the thousands of Hebrews in exile not only arrived at this idea, but developed the strict set of religious customs, of marriage laws and ceremonies, of dietary laws (i.e., keeping a kosher diet), and the duty of all Hebrew men to study the sacred books, all in order to preserve their identity. Once the Torah was compiled as a single sacred text by the prophet Ezra, one of the official duties of the scholarly leaders of the Jewish community, the rabbis, was to carefully re-copy it, character by character, ensuring that it would stay the same no matter where the Jews went. The result was a “mobile tradition” of Judaism in which the Jews could travel anywhere and take their religion with them. This would become important in the future, when they were forcibly taken from Judah by the Romans and scattered across Europe and North Africa. The ability of the Jews to bring their religious tradition with them would allow them to survive as a distinct people despite ongoing persecution in the absence of a stable homeland.

Another important aspect of Judaism was its egalitarian ethical system. The radical element of Jewish religion, as well as the Jewish legal system that arose from it, the Talmud, was the idea that all Jews were equal before God, rather than certain among them having a closer relationship to God. This is the first time a truly egalitarian element enters into ethics; no other people had proposed the idea of the essential equality of all human beings (although some aspects of Egyptian religion came close). Of all the legacies of Judaism, this may be the most important, although it would take until the modern era for political movements to take up the idea of essential equality and translate it into a concrete social, legal, and political system.

Conclusion

What all of the cultures considered in this chapter have in common is that they were more dynamic and, in the case of the empires, more powerful than earlier Mesopotamian (and even Egyptian) states. In a sense, the empires of the Bronze Age and, especially, the Iron Age represented different experiments in how to build and maintain larger economic systems and political units than had been possible earlier. The other major change is that it now becomes possible to discuss and examine the interactions between the various kingdoms and empires, not just what happened with them internally, since the entire region from Greece to Mesopotamia was now in sustained contact through trade, warfare, and diplomacy.

Likewise, some of the ideas and beliefs that originated in the Bronze and Iron Ages – most obviously Judaism – would go on to play a profound role in shaping the subsequent history of not just Western Civilization, but much of world history. Monotheism and the concept of the essential spiritual equality of human beings began as beliefs among a tiny minority of people in the ancient world, but they would go on to become enormously influential in the long run.

Check Your Understanding:

an extinct Semitic language of ancient Mesopotamia

The gods of a people, especially the officially recognized gods.

An epic poem about the Trojan War which focuses on Achilles. Usually attributed to Homer.

An epic poem about Odysseus, king of Ithaca, who wanders for 10 years trying to get home after the Trojan War. Usually attributed to Homer.

A system of administration or government characterized by specialization of functions, adherence to fixed rules, and a hierarchy of authority.

An alphabet where each symbol represents a sound.

Exaltation of military virtues and ideals.

A person or spiritual figure chosen, named, or honored as a special guardian, protector, or supporter.

Chief deity of the Assyrians

To send out of the country

An army component mounted on horseback.

Soldiers trained, armed, and equipped to fight on foot

In astronomy and astrology, a belt around the heavens that encompasses the apparent paths of all the planets and is divided into 12 constellations or signs each taken for astrological purposes.

A traditional story of ostensibly historical events that serves to unfold part of the world view of a people or explain a practice, belief, or natural phenomenon.

Words like "mythology" and "mythic" come from the word "Myth."

The father or founder of a group. Used also for one of the scriptural fathers of the Hebrew people.

A formal, solemn, and binding agreement.

The ornate, gold-plated wooden chest that in biblical times rested in the holiest part of the Temple in Jerusalem and housed the two tablets of the Law given to Moses by God.

The forced detention of Jews in Babylonia from about 597 BCE - 538 BCE

The worship of one god without denying the existence of other gods

The belief that there is only one god.

belief in or worship of more than one god.

The five books of Moses (Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus. Numbers, and Deuteronomy)

All-powerful

Existing everywhere at all times

A Jew qualified to expound and apply Jewish law; Rabbis act as spiritual leaders and religious teachers.