11 Islam and the Caliphates

Introduction

The history of Islam is an integral part of the history of Western Civilization. Consider the following:

- Islam was born in the heartland of Western Civilization: the Middle East.

- Islam is a religion of the same religious tradition as Judaism and Christianity. In Islam, the prophets that came before Muhammad, from Abraham and Moses to Jesus, are venerated as genuine messengers of God. The distinction is that, for Muslims, Muhammad was the last prophet, bringing the “definitive version” of God’s message to humanity. The word Allah simply means “God” in Arabic – He is the same God worshiped by Jews and Christians.

- The Islamic empires were the most advanced in the world, alongside China, during the European Middle Ages. During that period, they created and preserved all important scholarship worthy of the name. As noted in the previous chapter, it was Arab scholarship that preserved ancient Greek learning, and Arab scholars were responsible for numerous technological and scientific discoveries as well.

- The Islamic empires were often the enemies of various Christian ones. They were certainly the target of the European crusades. But, at the same time, the Christian kingdoms were often the enemies of one another as well. Likewise, different Islamic states were often in conflict. The political, and military, history of medieval Europe and the Middle East is one of different political entities both warring and trading; religion was certainly a major factor, but there are many cases where it was secondary to more prosaic economic or political concerns.

- The Islamic states were the active trading partners and sometimes allies of their neighbors from India and Central Asia to Africa and Europe. Islam’s initial spread was due to an enormous, unprecedented military campaign, but after that campaign ended, the resulting empires and kingdoms entered into more familiar economic and diplomatic relationships with their respective neighbors.

Thus, it is important to include the story of Islam as an inherent, intrinsic part of the history of Western Civilization. After the rise of Christianity and the conversion of the Roman Empire, the idea of a single, unified empire of Christianity, “Christendom,” became central to the identity of Christians in Europe. Once Rome itself fell, this idea became even more important. The Germanic kingdoms, what was left of the western empire, the new rising empires like the Kievan Rus, and of course Byzantium were all linked in the concept of Christendom. For many of those Christian states, Islam was indeed the enemy, because the rise of Islam coincided with one of the most extraordinary series of military conquests in world history: the Arab conquests.

Thus, from its very beginning, there have been historical reasons that Christians and Muslims sometimes considered themselves enemies. The first generations of Muslims did indeed try to conquer every culture and kingdom they encountered, although not initially in the name of conversion. The important thing to bear in mind, however, is that throughout the Middle Ages, many of the struggles between Christian and Muslim kingdoms, and Christian and Muslim people, were as often about conventional battles over power, wealth, and politics as religious belief. Likewise, once the years of conquest were over, Islamic states settled into familiar patterns of peaceful trade and they contained religiously diverse populations.

Origins of Islam

The pre-Islamic Arabian peninsula, most of which is today the kingdom of Saudi Arabia, was populated by the Arab people. The Arabs were herders and merchants. They were organized in clans, with each clan claiming descent from common ancestors and governing through meetings of the patriarchs of the leading families. The Arabs were well known in the Roman and Byzantine world as merchants for their camel caravans that linked Europe to a part of the Silk Road, transporting goods from India and China. They were also known to be some of the most fierce and effective mercenary warriors in the eastern Mediterranean region; they rode slim, fast, agile horses and fought as light cavalry.

Arab trade, and population, was concentrated in the more fertile southern and western regions, especially in what is today the country of Yemen. By the late Roman Empire, small but prosperous Arab kingdoms were in diplomatic contact with both Rome and Persia (as well as the Christian kingdom of Ethiopia, then called Aksum). As the wars between Rome and Persia became even more destructive after the Sasanian takeover in 234 CE, the Arabs emerged as important mercenaries and political clients for both empires. Persia in particular invested heavily in employing Arab soldiers and in cultivating the maritime trade route across the Indian Ocean and along the south and west coasts of Arabia. For a time, the southern coast of Arabia was ruled by Persia through Arab clients, and Persia was clearly a major cultural influence (so great was the renown of the Persian Great King Khusrau that his name became the root of an Arabic word for king: kisra). This contact and trade enriched the Arabic economy and led to a high degree of tactical sophistication among Arab soldiers.

The Arabs were polytheists – they worshiped a variety of gods linked to various oases in the desert. One important holy site that would take on even greater importance after the rise of Islam was the city of Mecca. Mecca had been a major center of trade for centuries, lying at the intersection of trade routes and near oases. In the center of Mecca was a shrine, called the Ka’aba, built around a piece of volcanic rock worshiped as a holy object in various Arabic faiths, and Mecca was a major pilgrimage site for the Arabs well before Islam.

Muhammad

Everything changed in the Arab world in the sixth century CE. A man named Muhammad was born in 570 CE to a powerful clan of merchants, the Quraysh, who controlled various trade enterprises in Mecca and surrounding cities. He grew up to be a merchant, marrying a wealthy and intelligent widow named Khadija (who was originally his employer) and traveling with caravans. He was particularly well known as a fair and perceptive arbitrator of disputes among other Arab clans and merchants. He traveled widely on business, dealing with both Christians and Jews in Palestine and Syria, where he learned about their respective religions.

An introspective man who detested greed and corruption, Muhammad was in the habit of retreating to the hills near Mecca, where there was a cave in which he would camp and meditate. When he was about forty, he returned to Mecca and reported that he had been contacted by the archangel Gabriel, who informed him that he, Muhammad, was to bear God’s message to the people of Mecca and the world. The core of that message was that the one true God, the God of Abraham, venerated already by the Jews and Christians, had called the Arabs to cast aside their idols and unite in a community of worshipers.

Muhammad did not meet with much success in Mecca in his initial preaching. The temples of the many gods there were rich and powerful and people resented Muhammad’s attempts to get them to convert to his new religion, in large part because he was asking them to cast aside centuries of religious tradition. The real issue with Muhammad’s message was its call for exclusivity – if Muhammad had just asked the Meccans to venerate the God of Abraham in addition to their existing deities, it probably would not have incited such fierce resistance, especially from the clan leaders who dominated Meccan society. Those clan leaders were fearful that if Muhammad’s message caught on, it would threaten the pilgrims who flocked to Mecca to venerate the various deities: that would be bad for business.

Thus, in 622 CE, Muhammad and a group of his followers left Mecca, exiled by the powerful families that were part of Muhammad’s own extended clan, and traveled to the city of Yathrib, which Muhammad later renamed Medina (“the city of the Prophet”), 200 miles north. They were welcomed there by the people of Medina, who hoped that Muhammad could serve as an impartial mediator in the frequent disputes between clans and families. Muhammad’s trek to Medina is called the hejira (also spelled hijra in English) and is the starting date of the Islamic calendar.

In Medina, Muhammad met with much more success in winning converts. He quickly established a religious community with himself as the leader, one that made no distinction between religious and political authority. His followers would regularly gather to hear him recite the Koran, which means “recitations”: the repeated words of God Himself as spoken to Muhammad by the angel. In 624 CE, just two years after his arrival in Medina, Muhammad led a Muslim force against a Meccan army, and then in 630 CE, he conquered Mecca, largely by skillfully negotiating with his former enemies there – he promised to make Mecca the center of Islam, to require pilgrimage, and to incorporate it into his growing kingdom. He sent missionaries and soldiers across Arabia, as well as to foreign powers like Byzantium and Persia. By his death in 632 CE, Muhammad had already rallied most of the Arab clans under his leadership, and most willingly converted to Islam.

Islam

The word Islam means “submission.” Its central tenet is submission before the will of God, as revealed to humanity by Muhammad. An aspect of Islam that distinguishes it from Judaism and Christianity is that the Koran has a single point of origin, the recitations of Muhammad himself, and it is believed by Muslims that it cannot be translated from Arabic and remain the “real” holy book. In other words, translations can be made for the sake of education, but every word in the Koran, spoken in the classical Arabic of Muhammad’s day, is believed to be the true language of God – according to traditional Islamic belief, the angels speak Arabic in paradise.

According to Islam, Muhammad was the last in the line of prophets stretching back to Abraham and Moses and including Jesus, whom Muslims consider a major prophet and a religious leader, but not actually divine. Muhammad delivered the “definitive version” of God’s will as it was told to him by Gabriel on the mountainside. The core tenets of Islamic belief are referred to as the “Five Pillars”:

- There is only one God and Muhammad is his prophet.

- Each Muslim must pray five times a day, facing toward the holy city of Mecca.

- During the holy month of Ramadan, each Muslim must fast from dawn to sundown.

- Charity should be given to the needy.

- If possible, at least once in his or her life, each Muslim should undertake the haaj: the pilgrimage to the holy city of Mecca.

In turn, a central concept of Islam is that of the worldwide community of Muslims, the ummah, meaning “community of believers.” The ummah was a central idea from the lifetime of Muhammad onward, referring to a shared identity among Muslims that is supposed to transcend differences of language, ethnicity, and culture. All Muslims are to follow the five pillars, just as all Muslims are to meet other members of the ummah at least once in their lives while on pilgrimage.

One term associated with Islam, jihad, has sparked widespread misunderstanding among non-Muslims. The word itself simply means “struggle.” It does mean “holy war” in some cases, but not in most. The concept of jihad revolves around the struggle for Muslims to live according to Muhammad’s example and by his teachings. Its most common use is the “jihad of the heart,” of struggling to live morally against the myriad corrupting temptations of life.

The Koran itself was written down starting during Muhammad’s life (his revelations were delivered over the course of about 20 years, and were initially transmitted orally). The definitive version was completed in the years following his death. Of secondary importance to the Koran is the Hadith, a collection of stories about Muhammad’s life, behavior, and sayings, all of which provided a model of a righteous and ethical life. In turn, in the generations following his death, Muslim leaders created the sharia, the system of Islamic law based on the Koran and Hadith.

The Political History of the Arabs After Muhammad

When Muhammad died, there were immediate problems among the Muslim Arabs. He did not name a successor, but he had been the definitive leader of the Islamic community during his life; it seemed clear that the community was meant to have a leader. The Muslim elders appointed Muhammad’s father-in-law, Abu Bakr (r. 63–34), as the new leader after a period of deliberation. He became the first caliph, meaning “successor”: the head of the ummah, the man who represented both spiritual and political authority to Muslims.

Under Abu Bakr and his successors – Umar (another of Muhammad’s fathers-in-law; r. 634–644), and Uthman (r. 644–655) – Muslim armies expanded rapidly. This began as a means to ensure the loyalty of the fractious Arab clans as much as to expand the faith; both Abu Bakr and Umar were forced to suppress revolts of the clans, and Umar hit upon the idea of raiding Persia and Byzantium to keep them loyal. For the first time in history, the Arabs embarked on a sustained campaign of conquest rather than serving others as mercenaries.

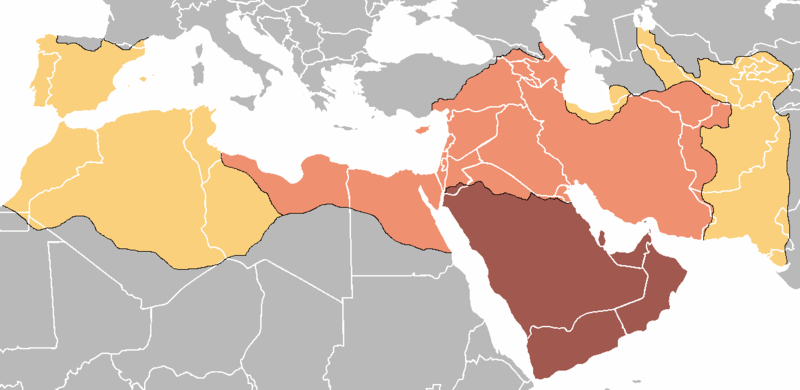

Riding their swift horses and camels and devoted to their cause, the Arab armies conquered huge amounts of territory extremely rapidly. It was the Arab army that finally conquered Persia in 637 (although it took until 650 for all Persian resistance to be vanquished), that hitherto-unconquered adversary of Rome. The Arabs conquered Syria and seized Byzantine territory in Anatolia equally quickly: Egypt was conquered by 642, with an attempted Byzantine counter-attack fought off in 645. Within twenty years of the death of Muhammad, the heartland of the Middle East was firmly in Arab Muslim hands.

Part of the success of the first decades of the Arab conquests was because of the vulnerability of Byzantium and Persia at the time, and another part was the tactical skill of Arab soldiers. The Arabs conquered Persia not just because it was weakened by its wars with Byzantium (most importantly its defeat by Heraclius in 627), but also because many Arab clans had fought as mercenaries for both sides in the conflict. Great wealth had been flowing into Arabia for decades, and the Arabs were already veteran soldiers. They had learned both Roman and Persian tactics and strategy and they were skilled at siege craft, intelligence-gathering, and open battle alike.

The Arab armies were easily the match of the Byzantine and Persian forces. The Arabs were able to field armies of about 20,000–30,000 men, with a total force of closer to 200,000 by about 700 CE. Most were Arabs from Arabia itself, along with Arabs who had settled in Syria and Palestine and were then recruited. A smaller percentage were non-Arabs who converted and joined the armies. Tactically, the majority were infantry who fought with spears and swords and were lightly-armored.

The major tactical advantage of the Arab armies was their speed: horses and camels were important less as animals to fight from than as means of transportation for the lightly-armored and equipped armies. Soldiers were paid in coins captured as booty, and whole armies were expected to buy their supplies as they marched rather than relying on heavy baggage trains. Their conquests were a kind of sustained sprint as a result. Likewise, one specific military “technology” that the Arabs used to great effect was camels, since no other culture was as adept at training and using camels as were the Arabs. Camels allowed the Arab armies to cross deserts and launch sudden attacks on their enemies, often catching them by surprise.

Finally, especially in Byzantine territories, high taxes and ongoing struggles between the official Orthodox form of Christianity and various other Christian sects led many Byzantine citizens to welcome their new Arab rulers; taxes often went down, and the Arabs were indifferent to which variety of Christianity their new subjects happened to subscribe to. In addition, the Arabs made little effort to convert non-Arabs to Islam for several generations after the initial conquests. To be clear, there was plenty of bloodshed during the Arab conquests, including the deaths of many civilians, but the long-term experience of Arab rule in former Byzantine territories was no more, and probably less, oppressive than it had been under Byzantium.

The Umayyad Caliphate and the Shia

The second caliph, Umar, was murdered by a slave in 644 and the Muslim leaders had to pick the next caliph. They chose an early convert and companion of Muhammad, Uthman. Many members of the Muslim community, however, supported Muhammad’s cousin and son-in-law Ali, claiming he should be the head of the ummah, as someone who was part of Muhammad’s direct family line. That group was known as the “party” or “faction” of Ali: the Shia of Ali (note that Shia is also frequently spelled “Shi’ite” in English). For Shia Muslims, the central idea was that only descendants of Muhammad should lead the ummah. The majority of Muslims, known as Sunnis (“traditionalists”), however, argued that any sufficiently righteous and competent leader could be appointed caliph.

While the Shia rejected Uthman’s authority in theory, there was as yet no outright violence between the two factions within the larger Muslim community. In 656 Uthman died, the victim of a short-lived Egyptian rebellion against the Arabs. Ali was elected as the next caliph, seemingly ending the dispute over who should lead the ummah. Unfortunately for Muslim unity, however, a significant number of Arab leaders disagreed with Ali’s policies and chose to support a rival would-be caliph, a relative of Uthman named Mu’awiya, a member of the Umayyad clan governing Syria. Ali was murdered by a rebel (unrelated to the power struggle over the caliphate) in 661, cementing the Umayyad claim on power, but not resolving the doctrinal dispute between Shia and Sunni.

It was thus under the leadership of caliphs who were not themselves related to Muhammad’s family line that the Arab conquests not only continued but stabilized in the form of a true empire. The Umayyad clan created the first long-lasting and stable Muslim state: the Umayyad Caliphate. It was centered in Syria and lasted almost 100 years. It supervised the consolidation of the gains of the Arab armies to date, along with vast new conquests in North Africa and Spain. The Umayyads were capable administrators and skilled generals, and the majority of Muslims saw the Umayyad rulers as the legitimate caliphs.

What they could not do, however, was destroy the Shia, despite Ali’s death. Shia Muslims, representing about 10% of the population of the Ummah (then and now), viewed the Umayyad government as fundamentally illegitimate, rejecting the very idea of a caliphate and arguing instead that the faithful should be led by an imam: a direct biological and spiritual descendant of Muhammad’s family. When Ali’s son Hussein, then the leader of the Shia and a grandson of Muhammad himself, was killed by the Umayyads in 680, the permanent breach between Sunni and Shia was cemented.

By 700 CE, the Umayyads had conquered all of North Africa as far as the Atlantic. Then, in 711, they invaded Spain and smashed the Visigothic kingdom, definitively ending Arian Christianity across both North Africa and Spain. They were finally stopped in 732 by a Frankish army led by the Frankish lord Charles Martel at the Battle of Poitiers, which marked the end of the Arab conquests in Europe. Likewise, despite conquering large amounts of Byzantine territory, Constantinople itself withstood a huge siege in 718, and Byzantine forces then pushed back Arab forces in Anatolia.

In Africa, Umayyad armies also attacked Nubia, still one of the richest kingdoms in the region, but were unable to defeat it. For the first time, the caliphate signed a peace treaty with a non-Muslim state. This was an important precedent because it established the idea that a Muslim state could acknowledge the political legitimacy of a non-Muslim one. Afterward, the Umayyad Caliphate came to deal with non-Muslim powers primarily in terms of normal diplomacy rather than through the lens of holy war.

In 751, Arab forces went so far as to defeat a Chinese army in Central Asia outside of the caravan city of Samarkand (they fought an army of the Tang dynasty, which had been expanding along the Silk Road). The last Umayyad caliph had been murdered shortly before this conflict, however, and the Muslim forces thus had little reason to continue their expansion. This battle marked the furthest extent of the core Muslim-ruled territories. For several centuries to follow, the Muslim world thus consisted of the Middle East, North Africa, and Spain.

The Umayyad Government and Society

The Umayyads did not just complete and consolidate the conquests of the Arabs. They also established lasting forms of governance. They quickly abandoned the practice of having elders come together to appoint leadership, insisting on a hereditary line of caliphs. This alone caused a civil war in the late seventh century, as some of their Muslim subjects rose up, claiming that they had perverted the proper line of leadership in the community. The Umayyads won that war too.

The major problem for the Umayyads was the sheer size of their empire. Just like other rapid conquests, such as that of Alexander the Great 1,000 years earlier, in the course of just a few decades, a people found itself in control of enormous swaths of territory. The Arabs had a strong linguistic and cultural identity, and many of the Arab conquerors saw themselves as a people apart from their new subjects, regardless of religious belief. Thus, while non-Arabs were certainly encouraged to convert to Islam, the power structure of the caliphate remained resolutely Arabic. As with the Greeks under Alexander, the Romans during their centuries of conquest, and the Germanic tribes that sliced up the western Roman Empire, the Arabs found themselves a small minority ruling over various other groups.

To try to effectively govern this vast new empire, the Umayyads took over and adapted the bureaucracies of the people they conquered, including those of both the Byzantines and, especially, the Persians. They created new borders and provinces to better suit their administration and ensure that tax revenue made it back to the capital at Damascus, with the idiosyncratic additional factor of needing to pay an ongoing salary to all Arab soldiers, even after those soldiers had retired.

One change that was to last until the present was linguistic. Unlike the Greek case during the Hellenistic period, Arabic was to replace the vernacular of the lands conquered during the Arab conquests. The only exceptions were Persian, which would eventually become the modern language of Farsi (the vernacular of the present-day country of Iran), and Spanish (Arabic and Spanish coexisted until Christian kingdoms reconquered Spain many centuries later). This linguistic uniformity was a huge benefit to trade, and to cultural and intellectual exchange, because one could travel from Spain to India and speak a single language.

Arabs also followed the patterns of Greek and Roman conquerors by colonizing the places they conquered. At first, they settled in garrisons (meaning towns that have troops permanently stationed in them) and administrative towns, but they also set up communities within conquered cities. As Arabic became the language of daily life, not just of administration, Arabs and non-Arabs mixed more readily. Arabs also built new cities all across their empire, the most notable being a small town in Egypt that would eventually grow into Cairo. They built these cities on the Hellenistic and Roman model: planned grids of streets at right angles. In the center of each city was the mosque, which served not only as the center of worship but in various other functions. Mosques were both figuratively and literally central to the cities of the Umayyad Caliphate. They were the predominant public spaces for discussion among men. They were the courthouses and the banks. They provided schooling and instruction. They were also often attached to administrative offices and governmental functions. The Umayyads may have disrupted the traditional oral transmission of literatures by the peoples of their empire, but the mosques fostered a blossoming manuscript culture that would overlap with the oral one, laying the groundwork for what would become a remarkably literate society.

The Umayyads imposed taxes across their entire empire, even insisting that their fellow Arabs pay a tax on their land, which was met with enormous resistance because, to Arabs unused to paying taxes at all, it implied subordination. By channeling taxes through their new, efficient bureaucracy, the Umayyads were able to support a very large standing army. That allowed them not only to keep up the pressure on surrounding lands but to quash rebellions.

The Umayyads supervised a tremendous expansion in trade and commerce across the Middle East and North Africa as well. Muhammad had been a merchant, after all, and the longstanding commercial practices and regulations of Arabic society were codified in sharia law – in that sense, commercial law was directly linked to religious righteousness. Likewise, even from this early period, the caliphate supported maritime trade networks. Muslim traders regularly sailed all across the Mediterranean, the Persian Gulf, the Indian Ocean, and eventually as far as China and the Philippines. In waters controlled by the caliphate, piracy was contained, so trade prospered even more.

One effect of Arab seafaring is that Islam spread along sea routes well beyond the political control of any of the Arab empires and kingdoms to come; today the single largest predominantly Muslim country is Indonesia, thanks to Muslim merchants that brought their faith along the trade routes. By the time European explorers began to establish permanent ties to Asian kingdoms and empires in the sixteenth century, Islam was established in various regions from India to the Pacific, thousands of miles from its Middle Eastern heartland.

Other Faiths

One of the noteworthy aspects of the Arab conquests is the complex role of conversion. The Koran specifically forbids the forcible conversion of Jews and Christians. It does allow that non-Muslim monotheists pay a special tax, however. For the century of Umayyad rule, only about 10% of the population was Muslim. Non-Muslims, called dhimmis (followers of religions tolerated by law), had to pay a head tax and were not allowed to share in governmental decision-making or in the spoils of war. Many Jews and Christians found Arab rule preferable to Byzantine rule, however, because the Byzantine government had actively persecuted religious dissenters and the Arabs did not. Likewise, taxes were lower under the Arabs as compared to Byzantium. These traditions of relative tolerance would continue all the way up to the modern era in places like the Ottoman Empire. However, even without forcible pressure, many people did convert to Islam either out of a heartfelt attraction to Islam or because of simple pragmatism; in some cases, Muslim generals rejected the attempted conversions of local people because it threatened their tax base so much.

There was also the case of the nomadic peoples of North Africa, collectively referred to as “Berbers” by the Arabs. The Berbers were hardy, warlike tribesmen living in rugged mountainous regions across North Africa. They had already seen the Romans and the Vandals come and go and simply kept up their traditions with the arrival of the Arabs. They were, however, polytheists, which the Muslims were unwilling to tolerate. Thus, faced with the choice of forcible conversion or death, the Berbers converted and then promptly joined the Arab armies as auxiliaries. This lent tremendous strength to the Arab forces and helps explain the relative ease of their conquests, especially in Spain.

The members of other monotheistic faiths who chose not to convert were often left much more free to practice their religions than they would have been in Christian lands, because the Umayyads simply did not care about theological disagreements among their Jewish and Christian subjects so long as the taxes were paid. Over time, various sects of Christianity survived in Muslim lands that vanished in kingdoms that were officially, and rigidly, Christian. Likewise, Jews found that they were generally better off in Muslim lands than in Christian kingdoms because of their safety from official persecution. Jews became vitally important merchants, scholars, bankers, and traders all across the caliphate.

Zoroastrianism, however, declined in the long run. The first generations of Muslim rulers accepted Zoroastrians as People of the Book like Jews and Christians, but that acceptance atrophied over time. Muslims were less tolerant of Zoroastrianism because it did not venerate the God of Abraham and its traditions were markedly different from those of Judaism and Christianity. Likewise, as Muslim rule over Persia was consolidated over time, the practical necessity of respecting Zoroastrianism as the majority religion of the Persian people weakened. By the tenth century, most Zoroastrians who had not converted to Islam migrated to India, where they remain today in communities known as the Parsees.

The Abbasids

The Umayyads fell from power in 750 because of a revolutionary uprising against their rule led by the Abbasids, a clan descended from Muhammad’s uncle. The Abbasids were supported by many non-Arab but Muslim subjects of the caliphate (called mawali) who resented the fact that the Umayyads had always protected the status of Arabs at the expense of non-Arab Muslims in their empire. After seizing control of the caliphate, the Abbasids went on a concerted murdering spree, trying to eliminate all potential Umayyad competitors, with only a single member of the Umayyad leadership surviving. The Abbasids lost control of some of the territories that had been held by the Umayyads (starting with Spain, which formed its own caliphate under the surviving Umayyad), but the majority of the lands conquered in the Arab conquests a century earlier remained in their control.

The true golden age of medieval Islam took place during the Abbasid Caliphate. The Abbasids moved the capital of the caliphate from Damascus to Baghdad, which they founded in part to be nearer to the heart of Persian governmental traditions. There, they combined Islam even more closely with Persian traditions of art and learning. They also created a tradition of fair rulership, in contrast to the memory of Umayyad corruption. The Abbasid caliphs were the leaders of both the political and spiritual orders of their society, seeking to make sure everything from law to trade to religious practice was running smoothly and fairly. They enforced fair trade practices and used their well-trained armies primarily to ensure good trade routes, to enforce fair tax collection, and to put down the occasional rebellion. The Abbasid rulers represented, in short, a kind of enlightened despotism that was greatly ahead of Byzantium or the Latin kingdoms of Europe in terms of its cosmopolitanism. The Abbasids abandoned Arab-centric policies and instead adopted Muslim universalism, allowing any Muslim the possibility of achieving the highest state offices and political and social importance.

Perhaps the most important phenomenon within the Abbasid Caliphate was the great emphasis and respect the caliphs placed on learning. New discoveries were made in astronomy, metallurgy, and medicine, and learned works from a variety of languages were translated and preserved in Arabic. The most significant tradition of scholarship surrounding Aristotle’s works, in particular, took place in the Abbasid Caliphate.

The major library in Baghdad was called the House of Wisdom; it was one of the great libraries of the world at the time. The various advances that took place in the Abbasid Caliphate included

- Medicine: far more accurate diagnoses and treatments than existed anywhere else (outside of China).

- Optics: early telescopes, along with the definitive refutation of the idea that the eye sends out beams to detect things and instead receives information reflected off of objects.

- Chemistry: various methods including evaporation, filtration, sublimation, and even distillation. Despite the specific ban on intoxicants in the Koran, it was Abbasid chemists who invented distilled spirits: al-kuhl, meaning “the essence,” from which the English word alcohol derives.

- Mathematics: the creation of Arabic numerals, based on Hindu characters, which were far easier to work with than the clunky Roman equivalents. In turn, the Abbasids invented algebra and trigonometry.

- Geography and exploration: accurate maps of Asia and East Africa, thanks to the presence of Muslim merchant colonies as far as China, along with new navigational technologies like the astrolabe (a device that is used to determine latitude while at sea).

- Banking: the invention of checks and forms of commercial insurance for merchants.

- Massive irrigation systems: these made Mesopotamia nearly on par with Egypt as the richest farmland in the world.

In addition, the Abbasid Caliphate witnessed a major increase in literacy. Not only were Muslims (men and women alike) encouraged to memorize the Koran itself, but scholars and merchants were often interchangeable; unlike medieval Christianity, Islam did not reject commerce as being somehow morally tainted. Thus, Muslims, whose literacy was due to study of specifically Islamic texts, the Koran and the Hadith especially, easily used the same skills in commerce. The overall result was a higher literacy rate than anywhere else in the world at the time, with the concomitant advantages in technological progress and commercial prosperity.

Building on their longstanding tradition of manuscript culture, this literate populace became voracious readers who demanded a prolific literary marketplace. In response, writers adapted traditional oral stories into great epics, invented the philosophical novel, and created a remarkable literary tradition that eventually produced world-famous and influential works such as the poetry of Rumi and the fantastical Book of One Thousand and One Nights. The long-standing tradition of women’s poetry in the region also flourished during this golden age of Islamic literature. These women came to poetry from vastly different perspectives; some were taught to write in order to serve as enslaved courtesans, while others wrote in pursuit of greater spirituality. Both groups of women, however, created astonishingly expressive and popular poetry. Arabic-speaking women’s poetry from this period ranged from love poems to satirical mocking of their husbands to Sufi mysticism to court songs. In this regard, the women of the Abbasid period (and the Andalus to come) stand out from their contemporary peers by firmly establishing their poetry as a distinct form.

The success of the Abbasids in ruling a huge, diverse empire arose in part from their willingness to follow Persian traditions of rule (a pattern that would be repeated by later Turkic and Mongol rulers). The Abbasid caliphs employed Persian bureaucrats and ruled in a manner similar to the earlier Persian Great Kings, although they did not adopt that title. Their role as caliphs was in protecting the ummah and providing a political framework in which sharia law could prosper – it was in the Abbasid period that Islamic law was truly developed and codified. From the Persian tradition the Abbasid caliphs borrowed both practical traditions of bureaucracy and administration and an equally important tradition of political status: they were the rulers over many peoples, acknowledging local identities while expecting deference and, of course, taxes.

At its height, the Abbasid Empire was truly enormous– it covered more land area than had the Roman Empire. Its merchants traveled from Spain to China, and it maintained diplomatic relations with the rulers of territories thousands of miles from Baghdad. The caliphate reached its peak during the rule of the caliph Harun al-Rashid (r. 786–809). His palace was so enormous that it occupied one-third of Baghdad. He and the greatest early-medieval European king, Charlemagne, exchanged presents and friendly letters, albeit out of political expediency: Charlemagne was the enemy of the Cordoban Caliphate of Spain, the last vestige of Umayyad power, and the Abbasids acted as an external pressure that Charlemagne hoped would make the Byzantine emperors recognize the legitimacy of his imperial title (as an aside, one of Charlemagne’s prized possessions was his pet elephant, sent to his distant court by al-Rashid as a goodwill gift).

Already by al-Rashid’s reign, however, the caliphate was splintering; it was simply too large to run efficiently without advanced bureaucratic institutions. North Africa west of Egypt seceded by 800, emerging as a group of rival Islamic kingdoms. Other territories followed suit during the rest of the ninth century, leaving the caliphate in direct control of only the core lands of Mesopotamia. Within its remaining territory the caliphs faced uprisings as well. Even the idea of a united (Sunni) ummah was a casualty of this political breakdown – the ruler of the Spanish kingdom claimed to be the “true” caliph, with a Shia dynasty in Egypt known as the Fatimids contesting both claims since it rejected the very idea of a Sunni caliph.

The political independence of the caliphate ended in 945 when it was conquered by Turkic nomads, who took control of secular power while keeping the caliph alive as a figurehead. In 1055, a different Turkic group, the Seljuks (the same group then menacing Byzantium), seized control and did exactly the same thing. For the next two centuries the Abbasid caliphs enjoyed the respect and spiritual deference of most Sunni Muslims but exercised no political power of their own.

As Seljuk power increased, that of the caliphate itself waned. Numerous independent, and rival, Islamic kingdoms emerged across the Middle East, North Africa, and northern India, leaving even the Middle Eastern heartland vulnerable to foreign invasion, first by European crusaders starting in 1095, and then most disastrously during the Mongol invasion of 1258 (under a grandson of Genghis Khan). It was the Mongols who ended the caliphate once and for all, murdering the last caliph and obliterating much of the infrastructure built during Abbasid rule in the process.

Europe

Two parts of Europe came under Arab rule: Spain and Sicily. Spain was the last of the large territories to be conquered during the initial Arab conquests, and Sicily was eventually conquered during the Abbasid period. In both areas, the rulers, Arab and North African immigrants, and new converts to Islam lived alongside those who remained Christian or Jewish. During the Abbasid period in particular, Spain and Sicily were important as bridges between the Islamic and Christian worlds, where all faiths and peoples were tolerated. The city of Cordoba in Spain was a glorious metropolis, larger and more prosperous than any in Europe and any but Baghdad in the Arab world itself – it had a population of 100,000, paved streets, street lamps, and even indoor plumbing in the houses of the wealthy. All of the Arabic learning noted above made its way to Europe primarily through contact between people in Spain and Sicily.

The greatest period of contrast between the eastern lands of Byzantium and the caliphates, on the one hand, and most of Europe, on the other, was between the eighth and eleventh centuries. During that period, there were no cities in Europe with populations of over 15,000. The goods produced there, not to mention the quality of scholarship, were of abysmal quality compared to their Arab (or Byzantine) equivalents, and Christian Europe thus imported numerous goods from the Arab world, often through Spain and Sicily. Europe was largely a barter economy while the Muslim world was a currency-based market economy, with sharia law providing a sophisticated legal framework for business transactions. Especially as Byzantium declined, the Muslim kingdoms stood at the forefront of scholarship, commerce, and military power.

Conclusion

As should be clear, the civilizations of the Middle East and North Africa were transformed by Islam, and the changes that Islam’s spread brought with it were as permanent as were the results of the Christianization of the Roman Empire earlier. The geographical contours of these two faiths would remain largely in place up to the present, while the shared civilization that brought them into being continued to change.