4 The Archaic Age of Greece

Introduction

Many Western Civilization textbooks begin with the ancient Greeks. As noted in the introduction of this book, however, there are some problems with taking that approach, most importantly the fact that starting with the Greeks overlooks the fact that the Greeks did not invent the essential elements of civilization itself.

That being noted, the Greeks were unquestionably historically important and influential. They can be justly credited with creating forms of political organization and approaches to learning that were and remain hugely influential. Among other things, the Greeks carried out the first experiments in democratic government, invented a form of philosophy and learning concerned with empirical observation and rationality, created forms of drama like comedy and tragedy, and devised the method of researching and writing history itself. It is thus useful and productive to consider the history of ancient Greece even if the conceit that other forms of ancient history are less important is abandoned.

The Greek Dark Age

During the Bronze Age, as described in the last chapter, the Minoans and Mycenaeans were two of the civilizations that were part of the international trade and diplomacy network of the Mediterranean and Middle East. The Minoans were a major seafaring civilization based on the island of Crete. They created huge palace complexes, magnificent artwork, and great wealth. They eventually vanished as a distinct culture, most likely after they were conquered and absorbed by the Mycenaeans, their neighbors to the north.

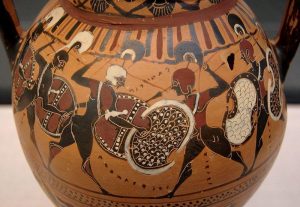

The Mycenaeans developed as a civilization after the Minoans were already established in Crete. The Mycenaeans lived on the Greek mainland and the islands of the Aegean Sea and were known primarily as sea-going merchants and raiders. They were extremely warlike, attacking each other, their neighbors, and the people they also traded with whenever the opportunity existed to loot and sack. The Mycenaeans were the protagonists of the famous epic poems written by the (possibly mythical) Homer, the Iliad and the Odyssey.

The Mycenaeans vanished as a civilization at the end of the Bronze Age. The cause was probably a combination of foreign invasions and local rebellions and wars. One strong possibility is that there was a sustained civil war among the Mycenaean palace-settlements that resulted in a fatal disruption to the economic setting that was essential to their very existence. A bad enough war in Greece itself could have easily undermined harvests, already near a subsistence level, and when they were destroyed by these conflicts, towns, fortresses, and palaces could not be rebuilt. Whatever the cause, the decline of the Mycenaeans occurred around 1100 BCE, marking the beginning of what historians refer to as the Dark Age in Greek history.

Of all the regions and cultures affected by the collapse of the Bronze Age, Greece was among those hit hardest. First and foremost, foreign trade declined dramatically. Whereas the Mycenaeans had been seafaring traders, their descendants were largely limited to local production and trade. Agriculture reverted to subsistence levels, and trade with neighboring areas all but vanished. In turn, this reversion to local subsistence economies cut them off from important sources of nutrition and materials for daily life, as well as foreign ideas and cultural influences. The Greeks went from being a great traveling and trading culture to one largely isolated from its neighbors. The results were devastating: some scholarly estimates are that the population of Greece declined by as much as 90% in the centuries following the Bronze Age collapse.

The Archaic Age and Greek Values

The Greek Dark Age started to end around 800 BCE. The subsequent period of Greek history, from around 800–490 BCE, is referred to as the “Archaic” (meaning “old”) Age. The Archaic Age saw the re-emergence of sustained contact with foreign cultures, starting with the development of Greek colonies on the Greek islands and on the western coast of Anatolia; this region is called Ionia, with its Greek inhabitants speaking a dialect of Greek called Ionian. These Greeks reestablished long-distance trade routes, most importantly with the Phoenicians, the great traders and merchants of the Iron Age. Eventually, foreign-made goods and cultural contacts started to flow back to Greece once again.

Of the various influences the Ionian Greeks received from the Phoenicians, none was more important than their alphabet. Working from the Phoenician version, the Ionian Greeks developed their own syllabic alphabet (the earlier Greek writing system, Linear B, vanished during the Greek Dark Age). This system of writing proved flexible, nuanced, and relatively easy to learn. Soon, the Greeks started recording not just tax records and mercantile transactions, but their own literature, poetry, and drama. The earliest surviving Greek literature dates from around 800–750 BCE thanks to the use of this new alphabet (which, in turn, served as the basis of the Roman alphabet and from there to the alphabets used in all Latinate European languages, including English).

Homer’s epic poems – The Iliad and The Odyssey – were written down in this period after being recited in oral form by traveling singers for centuries. They purported to recount the deeds of great heroes from the Mycenaean age, in the process providing a rich tapestry of information about ancient Greek values, beliefs, and practices to later cultures. Both poems celebrated arete – a Greek virtue that can be translated in English as “excellence” and “success,” but must be understood as a moral characteristic as much as a physical or mental one. Arete meant, among other things, fulfilling one’s potential, which was almost always the highest goal espoused in Greek philosophy. Throughout the epics, men and women struggle to overcome both one another and their own limitations while grappling with the limitations imposed by nature, chance, and the will of the gods.

The values on display in the Homeric poems spoke to the Greeks of the Archaic Age in how they determined what was good and desirable in human behavior in general. The focus of the Greeks was on the two ways that a man (and it was always a man in Greek philosophy – a theme that will be explored in detail in a subsequent chapter) could dominate other men: through strength of arms and through skill at words. The two major areas a man had to master were thus war and rhetoric: the ability to defeat enemies in battle and the ability to persuade potential allies in the political arena.

What was important to the Greeks was the public performance of excellence, not private virtue or good intentions. What mattered was how a man performed publicly, in battle, in athletic competitions, or in the public forums of debate that emerged in the growing city-states of Archaic Greece. The fear of shame was a built-in part of the pursuit of excellence: Greek competitions (in everything from athletics to poetry) had no second-place winners, and the losers were openly mocked in the aftermath of the contests. This idea of public debate and competition was to have an enormous influence on the development of Greek culture, one that would subsequently spread around the entire Mediterranean region.

Greek values translated directly into Greece’s unique political order. The Archaic Age was the era when major Greek political innovations took place. Of these, the most important was the creation of the polis (plural: poleis): a political unit centered on a city and including the surrounding lands. The English word “political” derives from “polis” – the polis was the center of Greek politics in each city-state, and Greek innovations in the realm of political theory would have an enormous historical legacy. From the Greek poleis of the Archaic and subsequent Classical Age, the notion of legal citizenship and equality, the practice of voting on laws, and a particular concept of political pride now referred to as patriotism all first took shape.

In the Archaic Age, Greek city-states shared similar institutions. Greek citizens could only be members of a single polis, and citizens had some kind of role in political decision-making. Citizens would gather in the agora, an open area that was used as a market and a public square, and discuss matters of importance to the polis as a whole. The richest and most powerful citizens became known as aristocrats – the “best people.” Eventually, aristocracy became hereditary. Other free citizens could vote in many cases on either electing officials or approving laws, the latter of which were usually created by a council of elders (all of whom were aristocrats) – the elders were called archons. At this early stage, commoners had little real political power; the importance was the precedent of meeting to discuss politics.

Even in poleis in which citizens did not directly vote on laws, however, there was a strong sense of community, out of which developed the concept of civic virtue: the idea that the highest moral calling was to place the good of the community above one’s own selfish desires. This concept was almost unparalleled elsewhere in the ancient world. While other ancient peoples certainly identified with their places of origin, they linked themselves to lineages of kings rather than the abstract idea of a community in most cases. Also, all Greek citizens were equal before the law, which was a radical break since most other civilizations had different sets of laws based on class identity (there were considerable ironies in Greek notions of “equality” however – see the later chapter on classical Greece). Civic virtue, very closely related to the modern concept of patriotism, was a powerful and influential idea because it would continue through the Greek Classical Age, be transmitted by Alexander the Great’s conquests, and eventually become one of, if not the single most important ethical standards of the Roman Republic and Empire. It would ultimately go on to influence thinkers and politicians up to the present.

One area of Archaic Greek culture bears additional focus: gender. Greek society was explicitly patriarchal, with men holding all official positions of political power. Likewise, both the Greek myths and epic tales are rife with hostility and suspicion of assertive, intelligent women, celebrating instead women who dutifully served their husbands or fathers (Penelope, wife of the Greek hero Odysseus, is described as waiting faithfully for twenty years for Odysseus to return from the invasion of Troy despite a legion of suitors trying to win her and Odysseus’s lands). Women were expected to be sexually monogamous with their husbands, while men’s sexual liaisons with female slaves as well as other men of their own social rank were perfectly acceptable behaviors.

That being noted, it is clear that women in the Archaic Age did enjoy both social influence and some access to economic power, being able to inherit property and receiving social approval for the skillful management of households. Likewise, women were not generally secluded from men in normal social discourse, with various Greek tales including moments of casual interaction between men and women. Practically speaking, women were invaluable to the Greek economy, providing almost all of the domestic labor and contributing to farming and commerce as well. Their status, however, would grow more fraught over time: as the Archaic Age evolved into the Classical Age (considered in a following chapter), restrictions on women’s lives and freedoms would increase, especially in key poleis like Athens, culminating in some of the most misogynistic gender standards in the ancient world.

Greek Culture and Trade

The Greek poleis were each distinct, fiercely proud of their own identity and independence, and they frequently fought small-scale wars against one another. Even as they did so, they recognized each other as fellow Greeks and therefore as cultural equals. All Greeks spoke mutually intelligible dialects of the Greek language. All Greeks worshiped the same pantheon of gods. All Greeks shared political traditions of citizenship. Finally, the Greeks took part in a range of cultural practices, from listening to traveling storytellers who recited the Iliad and Odyssey from memory to holding drawn-out drinking parties called symposia.

The poleis also invented institutions that united the cities culturally, despite their political independence, the most important of which was the Panhellenic games. “Panhellenic” literally means “all Greece,” and the games were meant to unite all of the Greek poleis, including those founded by colonists and located far from Greece itself. The games were a combination of religious festival and competition in which aristocrats from each city competed in various sports, including javelin, discus, footraces, and a brutal form of unarmed combat called pankration.

The most significant of these games was the Olympics, named after Olympia, the site in southern Greece where they were held every four years. They started in 776 BCE and ended in 393 CE – in other words, they lasted for over 1,000 years. Thanks to the Olympics, the date 776 BCE is usually used as the definitive break between the Dark and Archaic ages of Greek civilization. The Olympics were extraordinary not just in their longevity, but because Greeks from the entire world of Greek settlements came to them, traveling from as far away as Sicily and the Black Sea. Wars were temporarily suspended and all Greek poleis agreed to let athletes travel with safe passage to take part in the games, in part because the Olympics were dedicated to Zeus, the chief Greek god. As noted above, there were no second prizes. Greek culture was hugely competitive; the defeated were humiliated and the winners totally triumphant. In the games, they sought, in the words of one Greek poet, “either the wreath of victory or death” (granted, that poet was indulging in some hyperbole, as there is no evidence that defeated athletes actually committed suicide).

With the end of the Dark Age, population levels in Greece recovered. This led to emigration as the population outstripped the poor, rocky soil of Greece itself and forced people to move elsewhere. Eventually, Greek colonies stretched across the Mediterranean as far as Spain in the west and the coasts of the Black Sea in the north. Greeks founded colonies on the North African coast and on the islands of the Mediterranean, most importantly on Sicily. Greeks set up trading posts in the areas they settled, even in Egypt. The colonies continued the mainland practice of growing olives and grapes for oil and wine, but they also took advantage of much more fertile areas away from Greece to cultivate other crops.

Greek colonists sometimes intermarried with local peoples on arrival, an unsurprising practice given that many expeditions of colonists were almost all young men. In other cases, however, colonists found relatively isolated areas appropriate for shipping and set up shop, maintaining close connections with their home polis as an economic outpost. The one factor that was common to all Greek colonies was that they were rarely far from the sea. They were so closely tied to the idea of a shared Greek civilization and the need for the sea for trade routes was so strong that colonists were not generally interested in trying to push inland.

As trade recovered following the end of the Dark Age, the Greeks re-established their commercial shipping network across the Mediterranean, with their colonies soon playing a vital role. Greek merchants eagerly traded with everyone from the Celts of Western Europe to the Egyptians, Lydians, and Babylonians. When Julius Caesar was busy conquering Gaul about 700 years later, he found the Celts there writing in the Greek alphabet, long since learned from the Greek colonies along the coast. Likewise, archaeologists have discovered beautiful examples of Greek metalwork as far from Greece as northern France.

Greek colonies far from Greece were as important as the older poleis in Greece itself, since they created a common Greek civilization across the entire Mediterranean world. Greek civilization was not an empire united by a single ruler or government. Instead, it was united by culture rather than a common leadership structure. That culture would go on to influence all of the cultures to follow in a vast swath of territory throughout the Mediterranean region and the Middle East.

Military Organization and Politics

A key military development unique to Greece was the phalanx: a unit of spearmen standing in a dense formation, with each using his shield to protect the man to his left. Each soldier in a phalanx was called a hoplite. Each hoplite had to be a free Greek citizen of his polis and had to be able to pay for his own weapons and armor. He also had to be able to train and drill regularly with his fellow hoplites, since maneuvering in the densely-packed phalanx required a great deal of practice and coordination. The hoplites were significant politically because they were not always aristocrats, despite the fact that they had to be free citizens capable of paying for their own arms. Because they defended the poleis and proved extremely effective on the battlefield, the hoplites would go on to demand better political representation, something that would have a major impact on Greek politics as a whole.

The most noteworthy military innovation represented by the hoplites was that their form of organization provided one solution to the age-old problem of how to pay for highly-trained and motivated soldiers: rather than a state paying for a standing army, the hoplites paid for themselves and were motivated by civic virtue. When rival poleis fought, the phalanxes of each side would square off and stab away at each other until one side broke, threw down their shields, and ran away (by far the deadliest part of the confrontation). The victors would then allow the losers time to gather their dead for a proper burial and peace terms would be negotiated.

By the seventh century BCE, the hoplites in many poleis were clamoring for better political representation, since they were excluded by the traditional aristocrats from meaningful political power. In many cases, the result was the rise of tyrannies: a government led by a man, the tyrant, who had no legal right to power but had been appointed by the citizens of a polis in order to stave off civil conflict (tyrants were generally aristocrats, but they answered to the needs of the hoplites as well). To the Greeks, the term tyrant did not originally mean an unjust or cruel ruler, since many tyrants succeeded in solving major political crises on behalf of the hoplites while still managing to placate the aristocrats.

The tyrants, lacking official political status, had to play to the interests of the people to stay in power as popular dictators. They sometimes seized lands of aristocrats outright and distributed them to free citizens. Many of them built public works and provided jobs, while others went out of their way to promote trade. The period between 650–500 BCE is sometimes called the “Age of Tyrants” in Greek history because many poleis instituted tyrants to stave off civil war between aristocrats and less wealthy citizens during this period. After 500 BCE, a compromise government called oligarchy tended to replace both aristocracies and tyrannies. In an oligarchy, anyone with enough money could hold office, the laws were written down and known to all free citizens, and even poorer citizens could vote (albeit only yes or no) on the laws passed by councils.

Sparta and Athens

Two of the most memorable poleis of the Archaic Age were Sparta and Athens. The two poleis were in many ways a study in contrasts: an obsessively militaristic and inward-looking society of “equals” who controlled the largest slave society in Greece, and a cosmopolitan naval power at the forefront of political innovation.

Sparta

One scholarly work on Greek history, Frank Frost’s Greek Society, describes the Spartans as “an experiment in elitist communism.” From approximately 600 BCE – 450 BCE, the Spartans were unique in the ancient world in placing total emphasis on a super-elite, and very small, citizenship of warriors. Starting in about 700 BCE, the Spartans conquered a large swath of territory in their home region of Greece, the southern Greek peninsula called the Peloponnesus. Sparta at the time was an aristocratic monarchy, with two kings ruling over councils of citizens. Under the two kings were a smaller council that issued laws and a large council made up of all Spartan males over 30 who approved or rejected the laws proposed by the council. Over time, citizenship was limited to men who had undergone the arduous military training for which the Spartans are best remembered.

Spartan culture included among the most extreme forms of militarism the world has ever seen. Spartan boys were taken from their parents when they were seven to live in barracks. They were regularly beaten, both as a form of discipline and to make them unafraid of pain. Children with deformities of any kind were left in the elements to die, as were children maimed by the training regimen. Spartan boys were trained constantly in combat, maneuvering, and physical endurance. Spartan girls were allowed to stay with their parents but were trained in martial skills as children as well, along with the knowledge they would need to run a household. When a man reached the age of twenty, assuming he was judged worthy, he would be elevated to the rank of “Equal” – a full Spartan citizen – and receive a land grant that ensured that he could concentrate on military discipline for the rest of his life without having to worry about making a living.

Even activities like courtship and acquiring nourishment were designed to test Spartans. When it was time for a young Spartan to marry, the young man would brawl his way into the family home of his bride-to-be, fighting her relatives until he could “kidnap” her – this was as close to courtship as the Spartans got. Married couples were not allowed to live together before the age of 30; up till then, the man was expected to sneak out of his bunker to see his wife, then sneak back in again before morning. In addition, Spartans in training were often forced to steal food (from their own slave-run farms); they were punished if caught, but the infraction was being caught, not the theft – the idea was that the future warrior had failed to live up to the required level of skill at stealth.

The reason for all of this militaristic mania was simple: Sparta was a slave society. Approximately 90% of the population of the area under Sparta’s control were helots, serfs descended from the population conquered by Sparta in the eighth century. Early Spartan conquests of their region of Greece had resulted in a very large area under their control, populated by people who were not Spartan. Rather than extend any kind of political representation to these subjects, the Spartans instead maintained absolute control over them, up to the right of killing them at will with no legal consequence.

Every year, the Spartans would “declare war” on the helots, rampaging through their river valley, and part of the training of young Spartans was serving on the Krypteia, the Spartan secret police that infiltrated Helot villages to watch for signs of rebellion. Adolescent Spartans in training would even be dispatched to simply murder any helots they encountered. All of this was to ensure that the helots would be too terrified and broken-spirited to resist Spartan domination. There were never more than 8,000 Spartan soldiers, along with another 20,000 or so free noncitizens (inhabitants of towns near Sparta who were not considered helots, but instead free but subservient subjects), overseeing a much larger population of helots. Simply put, Spartan society was a military hierarchy that arose out of the fear of a massive slave uprising.

Likewise, despite the famous, and accurate, accounts of key battles in which the Spartans were victorious, or at least symbolically victorious, they were loathe to be drawn into wars, especially ones that involved going more than a few days’ march from Sparta. They were so preoccupied with maintaining control over the helots that they were very hesitant to engage in military campaigns of any kind, and hence rarely engaged in battles against other poleis before the outbreak of war against Athens in the fourth century BCE.

The only area in which Spartan society was actually less repressive than the rest of the Greek poleis was in gender roles. According to Greeks from outside of Sparta, free Spartan women were much less restricted than women elsewhere in Greece. They were trained in war, they could speak publicly, and they could own land. They scandalized other Greeks by participating in athletics and appear to have benefited from a greater degree of personal freedom than women anywhere else in Greece – of course, this would have been a social necessity since the men of Sparta lived in barracks until they were 30, leaving the women to run household estates.

Athens

In many ways, Athens was the opposite of Sparta. Whereas the Spartans were militaristic and austere (the word spartan in English today means “severe and unadorned”), the Athenians celebrated art, music, and drama. While it still controlled a large slave population, Athens is also remembered as the birthplace of democracy. In turn, Sparta and Athens were, especially in the fifth and fourth centuries BCE, rivals for the position of the most powerful polis in Greece.

Athens was rich and populous – the population of Attica, its 1,000-square-mile region of Greece, was about 600,000 by 600 BCE, and Athens was a major force in Mediterranean trade. That wealth led to conflicts over its distribution among the citizens, in turn prompting some unprecedented political experiments. Starting early in the Archaic Age, Athens witnessed a series of struggles and compromises between the aristocrats – wealthy land-owning families who controlled most of the land and most of the political power – and everyone else, particularly the free citizens and farmers of Athens who were not aristocrats. One key development in Athenian politics arose from the fact that merchants and prosperous farmers could afford arms and armor but were shut out of political decision-making. This was a classic case of hoplites becoming increasingly angry with the political domination of the aristocracy.

The crisis of representation reached a boiling point in about 600 BCE when there was a real possibility of civil war between the common citizens and the aristocrats. The major problem was that the aristocrats owned most of the land that other farmers worked on, many of those farmers were increasingly indebted to the aristocrats, and by Athenian law, anyone who could not pay off his or her debts could be legally enslaved. An increasing number of formerly free Athenian citizens thus found themselves enslaved to pay off their debts to an aristocrat.

To prevent civil war, the Athenians appointed Solon (638–558 BCE), an aristocratic but fair-minded politician, to serve as a tyrant and to reform institutions. His most important step in restoring order was to cancel debts and to eliminate debt-slavery itself. He used public money to buy Athenian slaves who had been enslaved abroad and bring them back to Athens. He enacted other legal reforms that reduced the overall power of the aristocracy, and in a savvy move, he had the laws written down on wooden panels and posted around the city so that anyone who could read could examine them (up to that point, the only people who actually knew the laws were the aristocratic judges, which made it all too easy for them to abuse their power).

Solon was not some kind of rabble-rouser or proto-communist, however. He mitigated the worst of the social divides between rich and poor in Athens, but he still reserved the highest offices for members of the richest families. On the other hand, the poorer free citizens were completely exempt from taxes, which made it easier for them to stay out of debt and to contribute to Athenian society (and the military). Perhaps the most innovative and important of Solon’s innovations was the concept of an impersonal state, one in which the politicians come and go but which continues on as an institution obeying written laws; this is in contrast to “the state” as just the ruling cabal of elite men, which Athens had been prior to Solon’s intervention.

This pattern continued for about a century. Solon’s successors were a collection of new tyrants, some of whom seized more land from aristocrats and distributed it to farmers, most of whom sponsored new building projects, but none of whom definitively broke the power of the old families. Social divides and tension continued to be the essential reality of Athenian society.

In 508 BCE, however, a new tyrant named Cleisthenes was appointed by the Athenian assembly who finally took the radical step of allowing all male citizens to have a vote in public matters and to be eligible to serve in public office. This included free but poor citizens, the ones too poor to afford weapons and serve as hoplites. He had lawmakers chosen by lot (i.e., randomly) and created new “tribes” mixing men of different backgrounds together to force them to start to think of themselves as fellow Athenians, not just jealous protectors of their own families’ interests. Thus, under Cleisthenes, Athens became the first “real” democracy in history.

That being noted, by modern standards, Athens was still highly unequal and unrepresentative. Women were completely excluded from political life, as were free non-citizens (including many prosperous Greeks who had not been born in Athens) and, of course, slaves. The voting age was set at 20. Overall, about 40% of the population were native-born Athenians, of which half were men, and half were under 20, so only 10% of the actual population had political rights. This is still a very large percentage by the standards of the ancient world, but it should be considered as an antidote to the idea that the Greeks believed in “equality” in a modern sense.

Conclusion

Greece managed to develop its unique political institutions and culture as part of a larger Mediterranean “world,” trading with, raiding, and settling alongside many of the other civilizations of the Iron Age. For centuries, Greece itself was too remote geographically and too poor in terms of natural resources to tempt foreign invaders to try to seize control. Starting in the sixth century BCE, however, some Greek colonies fell under the sway of the greatest empire the world had seen to date, and a series of events culminated in a full-scale war between the Greeks and that empire: Persia.

Check Your Understanding:

The period of Greek history when foreign trade declined dramatically, agriculture reverted to subsistence levels, and trade with neighboring areas all but vanished, cutting Greek culture off from foreign ideas and cultural influences.

The period of Greek history, from around 800 BCE - 490 BCE, which saw the re-emergence of sustained contact with foreign cultures, starting with the development of Greek colonies on the Greek islands and on the western coast of Anatolia.

A form of writing employing syllabic characters and used at Knossos on Crete and on the Greek mainland from the 15th to the 12th centuries BCE for documents in Mycenaean Greek

A Greek virtue which can be translated in English as “excellence” and “success” and refers to fulfilling one's potential.

A greek city state. Plural: Poleis

In ancient Greek cities, an open space that served as a meeting ground for various activities of the citizens.

The moral qualities in a person that support the civil and political order and promote the public good.

The social organization marked by the supremacy of the father in the clan or family, the legal dependence of wives and children, and the reckoning of descent and inheritance in the male line

An aristocratic banquet at which men met to discuss philosophical and political issues and recite poetry.

Of or relating to all Greece or all the Greeks

The Olympic Games are an athletic festival that originated in ancient Greece. The first Olympic Games had achieved major importance in Greece by the end of the 6th century BCE. They began to lose popularity when Greece was conquered by Rome in the 2nd century BCE.

A block of heavily armed infantry standing shoulder to shoulder in files several ranks deep.

a heavily armed infantry soldier of ancient Greece