5 Persia and the Greek Wars

Persia

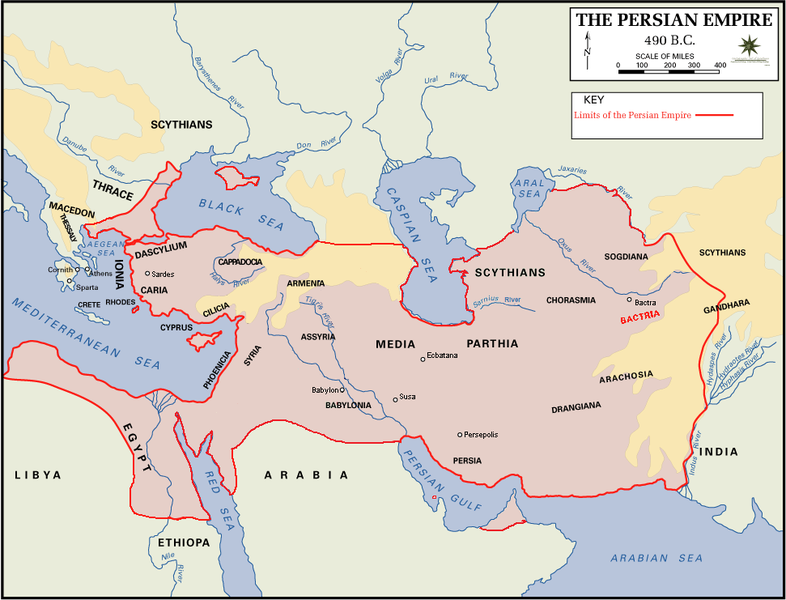

Persia was one of the most significant ancient civilizations, a vast empire that was at the time the largest the world had ever seen. It incorporated all of the ancient civilizations of the Middle East, and at its height it even included Egypt. In other words, the entire expanse of land stretching from the borders of India to Greece, including nearly all of the cultures described in the chapters above, were all conquered and controlled by the Persians.

Persia itself corresponds with present-day Iran (the language of Iran today, Farsi, is a direct linguistic descendent of ancient Persian). Most of its landmass is an arid plateau crossed by mountain ranges. In the ancient world, it was dominated by warriors on horseback who were generally perceived as “barbarians” by the settled people of Mesopotamia to the west, like the Greeks. By the seventh century BCE, a powerful collection of clans, the Medes, dominated Persia, forming a loosely-governed empire. In turn, the Medes ruled over a closely-related set of clans known as the Persians, who would go on to rule territories far beyond the Iranian heartland.

Historians divide Persian history into periods defined by the founding clan of a given royal dynasty. The empire described in this chapter is referred to as the Achaemenid Persian Empire after its first ruling clan. Later periods of ancient Persian history, most importantly the Parthian and Sasanian empires, are described in the chapters on ancient Rome.

Persian Expansion

The Medes were allies of Babylon, and in 612 BCE they took part in the huge rebellion that resulted in the downfall of the Assyrian Empire. For just over fifty years, the Medes continued to dominate the Iranian plateau. Then, in 550 BCE a Persian leader, Cyrus II the Great, led the Persians against the Medes and conquered them (practically speaking, there was little distinction between the two groups since they were so closely related and similar; the Greeks regularly confused the two when writing about them). He assimilated the Medes into his own military force and then embarked on an incredible campaign of conquest that lasted twenty years, forging Persia into a gigantic empire.

Cyrus began his conquests by invading Anatolia in 546 BCE, conquering the kingdom of Lydia in the process. His principal targets further west were the Greek colonies of Ionia, along the coast of the Aegean Sea. Cyrus swiftly defeated the Greek poleis, but instead of punishing the Greeks for opposing him, he allowed them to keep their language, religion, and culture, simply insisting they give him loyal warriors and offer tribute. He found Greek leaders willing to work with the Persians, and he appointed them as governors of the colonies. Thus, even though they had been beaten, most of the Greeks in the colonies did not experience Persian rule as particularly oppressive.

Cyrus next turned south and conquered the city-states and kingdoms of Mesopotamia, culminating with his conquest of Babylon in 539 BCE. This conquest was surprisingly peaceful; Babylon was torn between the priests of Marduk (the patron deity of the city) and the king, who was trying to favor the worship of a different goddess. After he defeated the forces of the king in one battle, Cyrus was welcomed as a liberator by the Babylonians and he made a point of venerating Marduk to help ensure their ongoing loyalty.

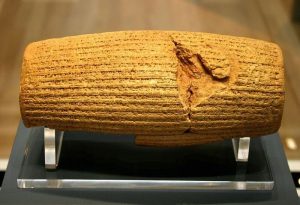

Much of what historians know about Persia is gleaned from the propaganda Persian kings left behind. The conquest of Babylon produced an outstanding example – the “Cyrus Cylinder,” a pillar covered in a proclamation that Cyrus commissioned after the conquest of Babylon.

The Cyrus Cylinder is a crucial source for understanding Persian rulership at its very beginning. Cyrus established his authority on two principles: descent from other great kings and the favor of the gods. He was the living representative of a supreme royal line of descent and the ensis in the Mesopotamian sense: the agent of the patron god on earth. Over time the identity of the god in question became Ahura Mazda, the supreme god of the Zoroastrian religion (described below) rather than Marduk, but the principle remained the same. All subsequent Persian kings would cite these two principles, which when combined elevated them in authority above all other rulers.

Cyrus continued the practice of finding loyal leaders and treating his conquered enemies fairly, which kept uprisings against him to a minimum. He then pushed into Central Asia, in present-day Afghanistan, conquering all of what constituted the “known world” in that region. To the northeast were the steppes, home of a steppe-dwelling nomadic people called the Scythians, whom the Persians would go on to fight for centuries (Cyrus himself died in battle against the Scythians in 530 BCE – he was 70 years old at the time).

Cyrus was followed by his son Cambyses II. Cambyses led the Persian armies west, conquering both the rich Phoenician cities of the eastern Mediterranean coast and Egypt. He was installed as pharaoh in Egypt, again demonstrating Persian respect for local traditions. Thus, in less than thirty years, Persia had gone from an obscure kingdom in the middle of the Iranian plateau to the largest land empire in the entire world, bigger even than China (under the Eastern Zhou dynasty) at the time. Cambyses died not long after, in 522 BCE, under somewhat mysterious circumstances – he supposedly fell on his sword while getting off of his horse.

In 522, following Cambyses’ death, Darius I became king (r. 521–486 BCE). Darius came to power after leading a conspiracy that may have assassinated Cambyses’ younger brother Bardiya, who had briefly ruled. In the midst of the political chaos at the top, a series of revolts briefly shook the empire, but Darius swiftly crushed the uprisings and reasserted Persian rule. He captured his moment of triumph in a huge carved image on a rock wall (the “Bisitun Inscription”) which depicts his victory over lesser kings and traces his royal lineage back to a shared ancestor with Cyrus the Great.

By the time Darius came to power, the Persian Empire was already too large to rule effectively; it was bigger than any empire in the world to date, but there was no infrastructure or government sufficient to rule it consistently. Darius worked to change that. He expanded the empire further and, more importantly, consolidated royal power. He improved infrastructure, established a postal service, and standardized weights, measures, and coinage. He set up a uniform bureaucracy and system of rule over the entire empire to standardize taxation and make it clear what was expected of the subject areas.

Darius inherited the conquests of his predecessors, and he personally oversaw the conquest of the northern part of the Indus river valley in northwestern India, thus marking the first time in world history when one state ruled over three of the major river systems of ancient history (i.e., the Nile, Mesopotamia, and the Indus). In 513 BCE he led a gigantic invasion of Central Asia to try to end the raids of the Scythians once and for all; he was forced to retreat without winning a decisive victory, but his army was still intact and he had added Thrace (present-day Bulgaria) to the empire.

Darius was also interested in seizing more territory to the west, conquering the remaining Greek colonies on the coast of Anatolia. In 499 BCE several Ionian Greek poleis rose against the Persians and successfully secured Athenian aid. Several years of fighting followed, with the Persians eventually crushing the rebellion in 494 BCE (the Persians deported many of the Greek rebels to India as punishment). Athens’ decision to support the rebellion angered the Persians, however, and Darius began to plan a full-fledged invasion of Greece.

The Persian Government

An empire this big posed some serious logistical challenges. The Persians may have had relatively loyal subjects, after all, but if it took months for messages to reach them, even loyal subjects could make decisions that the kings would disagree with. To help address this issue, Darius undertook a series of major reforms. The Persians continued the Assyrian practice of building highways and setting up supply posts for their messengers. The most important of these highways was called the Royal Road, linking up the empire all the way from western Anatolia to the Persian capital of Susa, just east of the Tigris. A messenger on the Royal Road could cover 1,600 miles in a week on horseback, trading out horses at posts along the way. The Persians standardized laws and issued regular coinage in both silver and gold. The state used several languages to communicate with its subjects, and the government sponsored a major effort to standardize a new, simplified cuneiform alphabet.

As described above, the key to Persian rule was the novel innovation of treating conquered people with a degree of leniency (in stark contrast to the earlier methods of rule employed by the Assyrians and Neo-Babylonians). So long as they were loyal, paid taxes, and sent troops when called, the Persian kings had no problem with letting their subjects practice their own religions, use their own languages, and carry on their own trading practices and customs. For example, it was Cyrus who allowed the exiled Jews to return to Judah from Babylon in the name of a kind of royal generosity. It seems that the Persian kings felt it very important to maintain an image of beneficence (mercy and kindness), of linking their power to sympathy for their subjects, rather than trying to terrorize their subjects into submission.

The Persian kings introduced a system of governance that allowed them to gather intelligence and maintain control over such a vast area relatively successfully. The empire was divided into twenty satrapies (provinces), ruled by officials called satraps. In each satrapy, the satrap was the political governor, advised and supplemented by a military general who reported directly to the king; in this way, the two most powerful leaders in each satrapy could keep an eye on each other. In addition, roaming officials called the “eyes and ears of the king” traveled around the empire checking that the king’s edicts were being enforced and that conquered people were not being abused, then reporting back to the Persian capitals of Susa and Persepolis (both cities served as royal capitals). Despite that system of political “checks and balances,” the satraps appointed the new king from the royal family when the old one died, and sometimes they preferred to appoint weak-willed members of the royal family so that the satraps might enjoy more personal freedom. Likewise, despite the innovations that Darius introduced in organization, the satraps normally operated with a large degree of autonomy.

The kings themselves adopted the title of “King of Kings.” They were happy to acknowledge the authority of the rulers of the lands they had conquered but required those rulers to in turn acknowledge the Persian king’s overarching supremacy. Persian images of the kings depicted them receiving tribute from other, lesser kings who had come to Susa or Persepolis in a show of loyalty and support. In this way, the political authority of the empire was tied together by both the formal bureaucratic structure of the satrapies as well as the bonds of loyalty between the King of Kings and his subject rulers.

One final component of the Persian system was relatively modest taxation. In order to keep taxes moderate, the Persian kings only called up armies (of both Persians and conquered peoples) when there was a war; otherwise, the only permanent army was the 10,000-strong elite bodyguard of the king that the Greeks called the “Immortals.” When the Persians did go to war, their subjects contributed troops according to their strengths. The Phoenicians formed the navy, the Medes the cavalry, the Mesopotamians the infantry, and so on. This system worked well on long campaigns, but its weakness was that it took up to two years to mobilize the whole empire for war, a serious issue in the conflicts between Persia and Greece in the long run.

The Achaemenid dynasty of Persia would rule for approximately two centuries, from Cyrus’s victories in 550 BCE to its conquest by Alexander the Great, completed in 330 BCE. It is worth noting that despite the relatively “enlightened” character of Persian rule, rebellions did occur (often starting in Egypt), most frequently during periods of transition or civil war between rival claimants to the throne. In a sense, the empire both benefited from and was made vulnerable by the autonomy of its subjects: each region maintained its own identity and traditions, keeping everyday resentment to a minimum, but in moments of crisis, that autonomy might also lead to the demand for actual independence.

Zoroastrianism

Despite the overall policy of religious tolerance, there was still a dominant Persian religion: Zoroastrianism. Zoroastrianism, named after its prophet Zoroaster, taught that the world was being fought over by two great powers: a god of goodness, honesty, and benevolence known as Ahura Mazda (meaning “Lord Wisdom”) and an evil spirit, Ahriman. Ahura Mazda was aided by lesser gods like Mithras, god of the sun and rebirth, and Anahita, goddess of water and the cosmos. Every time a person did something righteous, honest, or brave, Ahura Mazda won a victory over Ahriman, while every time someone did something cruel, dishonest, or dishonorable Ahriman pushed back against Ahura Mazda. Thus, humans had a major role to play in bringing about the final victory of Ahura Mazda through their actions.

Zoroaster himself lived far earlier (sometime between 1300 BCE and 1000 BCE), long before the rise of the empire, and was responsible for codifying the beliefs of the religion named after him. Zoroaster claimed that Ahura Mazda was the primary god and would ultimately triumph in the battle against evil, but explained the existence of evil in the world as a result of the struggle against Ahriman. Thus, Ahura Mazda was not “all-powerful” in quite the same way as the Jewish (and later Christian and Muslim) God was believed to be. Human actions mattered in this scheme because everyone played a role, however minor, in helping to bring about order and righteousness or impeded progress by indulging in wickedness. Zoroastrianism also told a specific story about the afterlife: when the power of good finally triumphs definitively over evil, those who lived righteously would live forever in the glorious presence of Ahura Mazda, while those who were evil would suffer forever in a black pit.

There are obvious parallels here between Zoroastrianism and Jewish and Christian beliefs. Indeed, there is a direct link between the Zoroastrian Ahriman and the Jewish and Christian figure of Satan, who was simply a dark spirit in the early books of the Torah but later became a distinct presence, the “nemesis” of God Himself and a threat to the order of the world. Likewise, the Christian idea of the final judgment is clearly indebted to the Zoroastrian one: a great day of reckoning.

In turn, Zoroastrianism provided a spiritual justification for the expansion of the Persian Empire. Because the great kings believed that they were the earthly representatives of Ahura Mazda, they claimed that the expansion of the empire would bring the final triumph of good over evil sooner. There was a parallel here to the beliefs of the ancient Egyptians, who had also (during their expansionist phase during the New Kingdom) claimed to be bringing order to a chaotic world at the end of a sword. The kings sponsored Zoroastrian temples and expanded the faith at least in part because the faith supported them: the magi, or priests, preached in favor of the continued power and expansion of the empire.

One noteworthy aspect of Zoroastrianism is that, in contrast to other ancient religions (including Judaism, and later, Christianity), Zoroastrianism appears to have banned slavery on spiritual grounds. This is important to bear in mind in the context of discussing the Persian War, described below. The Greeks thought of the war as the defense of their glorious traditions, including the political participation of citizens in the state, but it was the Greeks who controlled a society that was heavily dependent on slavery, whereas slavery was at least less prevalent in Persia than in Greece (despite the religious ban, slavery was clearly still present in the Persian Empire to some degree).

Almost all of the theological details about Zoroastrianism are known from much later periods of Persian history, although historians have established that the Persian rulers themselves were almost certainly Zoroastrians by the rule of Darius I. The importance of Zoroastrianism is in part the fact that it reveals much about what the Persians valued, not just what they believed about the universe. Truth was the cardinal virtue of Zoroastrianism, with lying being synonymous with evil. Each person had a certain social role to play in the Zoroastrian worldview, with the kings presiding over an ordered, loyal, prosperous society. In theory, war was fought to extend righteousness, not just seize territory and loot. Clearly, there was a sophisticated ethical code and set of social expectations present even in early Zoroastrianism, reflected in a comment made by the Greek historian Herodotus. According to him, the Persians taught their children three things: to ride a horse, to shoot a bow, and to tell the truth.

The Persian War

When the Greek cities of Ionia rose up against Persian rule, Darius I vowed to make an example not just of them, but of the Greek poleis that had aided them, including Athens. This led to the Persian War, one of the most famous conflicts in ancient history. It is remembered in part because it pitted an underdog, Greece, against a massive empire, Persia. It is remembered because the underdog won, at least initially. It is also remembered, unfortunately, for how the conflict was appropriated by proto-racist beliefs in the superiority of “the West.” Because the Greeks saw the conflict in terms of the triumph of true, Greek civilization over barbaric tyranny, and the surviving historical sources are told exclusively from the Greek perspective, this bias has managed to last down until the present. The war began in 490 BCE, when the Persians, with about 25,000 men, landed at Marathon, a town 26 miles from Athens. The Athenians sent a renowned runner, Pheidippides, to Sparta (about 140 miles from Athens) to ask for help. The Spartans agreed but said that they could only send reinforcements when their religious ceremonies were completed in a few days. Pheidippides ran back to Athens with the bad news, but by then the Athenians were already engaged with the Persians.

There were about 25,000 Persian troops – this was an “expeditionary force,” a force sent to accomplish a specific goal and not a large army, against which the Athenians fielded 10,000 hoplites. The Athenians marched out to confront the Persians. The two armies camped out and watched each other for a few days, then the Persians dispatched about 10,000 of their troops in naval transports to attack Athens directly; this prompted a gamble on the part of the leading Athenian general (named Miltiades) to attack the remaining Persians rather than running back to Athens to defend it. The ensuing battle was a decisive show of force for the Greeks: the citizen-soldier hoplites proved far more effective than the conscript infantry of the Persian forces. The core of the Persian army, its Median and Persian cavalry, fought effectively against the Athenians, but once the Athenian wings closed in and forced back the infantry, the Persians were routed.

The Greeks were especially good at inflicting casualties without taking very many – the Persians supposedly lost 33 men to every Athenian lost in the battle (6,400 Persian dead to 192 Athenians). There is also a questionable statistic from Greek sources that it was more than that – as many as 60 Persians per Athenian. Whatever the real number, it was a crushing victory for the Athenians. A later (almost certainly fabricated) account of the aftermath of the battle claimed that Pheidippides was then sent back to Athens, still running, to report the victory. He dropped dead of exhaustion, but in the process he ran the first “marathon.”

It is entirely possible that, despite this victory, the Greeks would have still been overwhelmed by the Persians if not for setbacks in Persia and its empire. A major revolt broke out in Egypt against Persian rule, drawing attention away from Greece until the revolt was put down. Likewise, it took years to fully “activate” the Persian military machine; preparation for a full-scale invasion took a full decade to reach completion. Darius I died in 486 BCE, in the middle of the preparations, which disrupted them further while his son Xerxes I consolidated his power.

In the meantime, the Greeks were well aware that the Persians would eventually return. A new Athenian general, Themistocles, convinced his countrymen to spend the proceeds of a silver mine they had discovered on a navy. Athens went into a naval-building frenzy, ending up with hundreds of warships called triremes, rowed by those free Athenians too poor to afford armor and weapons and serve as hoplites but who now had an opportunity to directly aid in battle as sailors. This was perhaps the first time in world history that a fairly minor power transformed itself into a major power simply by having the foresight to build an effective navy.

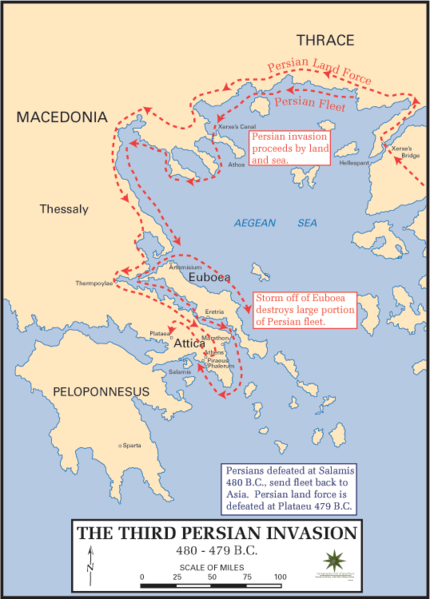

The Persians had finally regrouped by 480 BCE, ten years after their first attempt to invade. Xerxes I, the new king, dispatched a huge army (as many as 200,000 soldiers and 1,200 ships) against Greece, supported by a navy over twice as large as that of the Athenians. The Greek poleis were, for the most part, terrified into submission, with only about 6% of the Greek cities joining into the defensive coalition created by Athens and Sparta (that being said, within that 6% were some of the most powerful poleis in Greece). The Spartans took leadership of the land army that would block the Persians in the north while the Athenians attacked the Persian navy in the south.

The Spartan-led force was very small compared to the Persian army, but for several days they held the Persians back at the Battle of Thermopylae, a narrow pass in which the Persians were unable to deploy the full might of their (much larger) army against the Greeks. The Spartan king, Leonidas, and his troops held the Persian forces in place until the Spartans were betrayed by a Greek hired by the Persians into revealing a path that allowed the Persians to surround the Greeks and, finally, overwhelm them. Despite the ultimate defeat of the Spartan force, this delay gave the Athenians enough time to get their navy into position, and they crushed the Persian navy in a single day.

Despite the Persian naval loss, Xerxes’ I army was easily able to march across Greece and ransack various poleis and farmlands; it even sacked Athens itself, which had been evacuated earlier. Xerxes I then personally withdrew along with a significant portion of his army, while claiming victory over the Greeks. Here, simple logistics were the issue: the Greek naval victory made supply of the whole Persian army impractical.

The next year, in 479 BCE, a decisive battle was fought in central Greece by a Greek coalition led by the Spartans, followed by a Greek naval battle led by the Athenians. The latter then led an invasion of Ionia that defeated the Persian army. Each time the Greeks were victorious, and the Persians finally decided to abandon the attempt to conquer Greece as being too costly. The remaining Greek colonies in Anatolia rose up against the Persians, and sporadic fighting continued for almost 20 years.

While there is obviously a pro-Greek bias to the Greek sources that describe the Persian War, they do identify an essential reason for Greek victories: thanks to the viability of the phalanx, each Greek soldier (from any polis, not just Sparta) was a real, viable soldier. The immense majority of the Persian forces were relatively ineffective peasant conscripts, unwillingly recruited from their homes and forced to fight for a king to whom they had little personal loyalty. The core of the Persian army were excellent cavalry from the Iranian plateau and Bactria (present-day Afghanistan), but those were always a small minority of the total force.

The year 479 BCE marked the end of the Persian War and the beginning of the “classical age” of Greece. During this period, the Greeks exhibited the most remarkable flowering of their ideas and accomplishments, as well as perhaps their most selfish and misguided political blundering in the form of a costly and ultimately pointless war between Sparta and Athens: the Peloponnesian War.

The Peloponnesian War

When the Spartans and Athenians led the Greek poleis to victory against the Persians in the Persian War, it was a shock to the entire region of the Mediterranean and Middle East. Persia was the regional “superpower” at the time, while the Greeks were just a group of disunited city-states on a rocky peninsula to the northwest. After their success, the Greeks were filled with confidence about the superiority of their own form of civilization and their taste for inquiry and innovation. Greeks in this period, the Classical Age, produced many of their most memorable cultural and intellectual achievements.

The great contrast in the Classical Age was between the power and splendor of the Greek poleis, especially Athens and Sparta, and the wars and conflicts that broke out as they tried to expand their power and control. After the defeat of the Persians, the Athenians created the Delian League; in theory this was a defensive coalition that existed to defend against Persia and to liberate the Ionian colonies still under Persian control, but in reality it was a political tool eventually used by Athens to create its own empire.

Each year, the members of the Delian League contributed money to build and support a large navy, meant to protect all of Greece from any further Persian interference. Athens, however, quickly became the dominant player in the Delian League. Athens was able to control the League due to its powerful navy; no other polis had a navy anywhere near as large or effective, so the other members of the League had to contribute funds and supplies while the Athenians fielded the ships. Thus, it was all too easy for Athens to simply use the League to drain the other poleis of wealth while building up its own power. The last remnants of Persian troops were driven from the Greek islands by 469 BCE, about ten years after the great Greek victories of the Persian War, but Athens refused to allow any of the League members to resign from the League after the victory.

Soon, Athens moved from simply extracting money to actually imposing political control in other poleis. Athens stationed troops in garrisons in other cities and forced the cities to adopt new laws, regulations, and taxes, all designed to keep the flow of money going to Athens. Some of the members of the League rose up in armed revolts, but the Athenians were able to crush the revolts with little difficulty. The final event that eliminated any pretense that the League was anything but an Athenian empire was the failure of a naval expedition sent in 460 BCE by Athens to help an Egyptian revolt against the Persians. The Greek expedition was crushed, and the Athenians responded by moving the treasury of the League, formerly kept on the Greek island of Delos (hence “Delian League”), to Athens itself, arguing that the treasury was too vulnerable if it remained on Delos. At this point, no other member of the League could do anything about it – the League existed as an Athenian-controlled empire, pumping money into Athenian coffers and allowing Athens to build some of its most famous and beautiful buildings. Thus, the great irony is that the most glorious age of Athenian democracy and philosophy was funded by the extraction of wealth from its fellow Greek cities. In the end, the Persians simply made peace with Athens in 448 BCE, giving up the claim to the Greek colonies entirely and in turn eliminating the very reason the League had come into being.

Meanwhile, Sparta was the head of a different association, the Peloponnesian League, which was originally founded before the Persian War as a mutual protection league of the Greek cities of Corinth, Sparta, and Thebes. Like Athens, Sparta dominated its allies, although it did not take advantage of them in quite the same ways that Athens did. Sparta was resentful and, in a way, fearful of Athenian power. Open war finally broke out between the two cities in 431 BCE after two of their respective allied poleis started a conflict and Athens tried to influence the political decisions of Spartan allies. The war lasted from 431 to 404 BCE.

The Spartans were unquestionably superior in land warfare, while the Athenians had a seemingly unstoppable navy. The Spartans and their allies repeatedly invaded Athenian territory, but the Athenians were smart enough to have built strong fortifications that held the Spartans off. The Athenians, in turn, attacked Spartan settlements and positions overseas and used their navy to bring in supplies. While Sparta could not take Athens itself, Athens was essentially under siege for decades; life went on, but it was usually impossible for the Athenians to travel over land in Greece outside of their home region of Attica.

Truces came and went, but the war continued for almost thirty years. In 415 BCE Athens suffered a disaster when a young general convinced the Athenians to send thousands of troops against the city of Syracuse (a Spartan ally) in southern Sicily, hundreds of miles from Greece itself, in hopes of looting it. The invasion turned into a nightmare for the Athenians, with every ship captured or sunk and almost every soldier killed or captured and sold into slavery; this dramatically weakened the Athenian military.

At that point, the Athenians were on the defensive. The Spartans established a permanent garrison within sight of Athens itself. Close to 20,000 slaves escaped from the Athenian silver mines that had originally paid for the navy before the Persian War and were welcomed by the Spartans as recruits (thus bolstering Spartan forces and cutting off Athens’ main source of revenue). Sparta finally struck a decisive blow in 405 BCE by surprising the Athenian fleet in Anatolia and destroying it. Athens had to sue for peace. Sparta destroyed the Athenian defenses it had used during the war but did not destroy the city itself, and within a year the Athenians had created a new government.

The Aftermath

Greece itself was transformed by the Peloponnesian War. Both sides had sought out allies outside of Greece, with the Spartans ultimately allying with the Persians – formerly their hated enemies – in the final stages of the war. The Greeks as a whole were less isolated and more cosmopolitan by the time the war ended, meaning that at least some of their prejudices about Greek superiority were muted. Likewise, the war had inadvertently undermined the hoplite-based social and political order of the prior centuries.

Nowhere was this more true than in Sparta. Sparta had been transformed by the war, out of necessity becoming both a naval power and a diplomatic “player” and losing much of its former identity; some Spartans had gotten rich and were buying their sons out of the formerly-obligatory life in the barracks, while others were too poor to train. Likewise, the war had weakened Sparta’s cultural xenophobia and obsession with austerity, since controlling diplomatic alliances was as important as sheer military strength. Diplomacy required skill, culture, and education, not just force of arms. Subsequently, the Greeks as a whole were shocked in 371 BCE when the polis of Thebes defeated the Spartans three times in open battle, symbolically marching to within sight of Sparta itself and destroying the myth of Spartan invincibility.

Across Greece, the poleis adopted the practice of enlisting state-financed standing armies for the first time, rather than relying on volunteer citizen-soldiers. Likewise, the poleis came to rely on mercenaries, many of whom (ironically) went on to serve the Persians after the war wound down. Thus, between 405 and 338 BCE, the old order of the hoplites and republics atrophied, replaced by oligarchic councils or tyrants in the poleis and stronger, tax-supported states. The period of the war itself was thus both the high point and the beginning of the end of “classical” Greece. Meanwhile, Persia re-captured and exerted control over the Anatolian Greek cities by 387 BCE as Greece itself was divided and weakened. Thus, even though the Persians had “lost” the Persian War, they were as strong as ever as an empire.

Despite the importance of the Peloponnesian War in transforming ancient Greece, however, it should be emphasized that not all of the poleis were involved in the war, and there were years of truce and skirmishing during which even the major antagonists were not actively campaigning. The reason that this part of Greek history is referred to as the Classical Age is that its lasting achievements had to do with culture and learning, not warfare. The Peloponnesian War ultimately resulted in checking Athens’ imperial ambitions and causing the Greeks to broaden their outlook toward non-Greeks; its effects were as much cultural as political. Those effects are the topic of the next chapter.

Check Your Understanding:

a land, culture, or people [foreign to] and usually believed to be inferior to another land, culture, or people; words like barbarism or barbaric come from this term and are used to describe the condition of being like a "barbarian"

To adopt the ways of another culture : to fully become part of a different society, country, etc.

The territory or jurisdiction of a satrap (governor in ancient Persia)

The governor of a province in ancient Persia

A military force sent abroad

A military post of the troops stationed there

Fear and hatred of strangers or foreigners or of anything that is strange or foreign.

A greek city state. Plural: Poleis