Chapter 3: Ancient and Early Medieval India

George Israel

3.1 CHRONOLOGY

| Chronology | Ancient and Early Medieval India |

|---|---|

| 2600–1700 BCE | Harappan/Indus Valley Civilization |

| 1700–600 BCE | Vedic Age |

| 1700–1000 BCE | Early Vedic Age |

| 1000–600 BCE | Later Vedic Age |

| 321–184 BCE | Mauryan Empire |

| c. 2nd century BCE to 3rd century CE | Kushan Kingdom |

| c. 321–550 CE | Gupta Empire |

| 600–1300 CE | Early Medieval India |

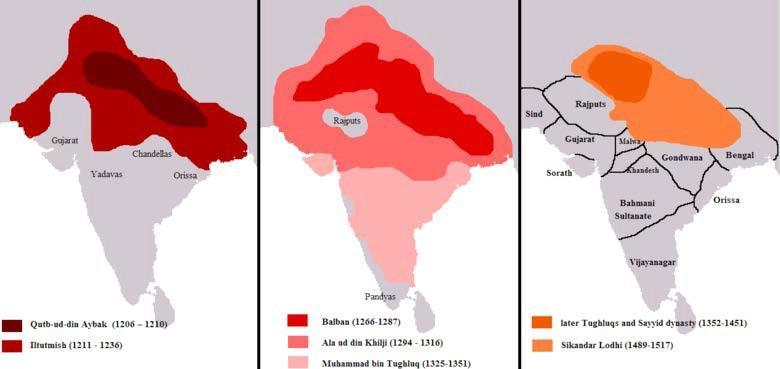

| 1206–1526 CE | Delhi Sultanate |

3.2 INTRODUCTION: A POLITICAL OVERVIEW

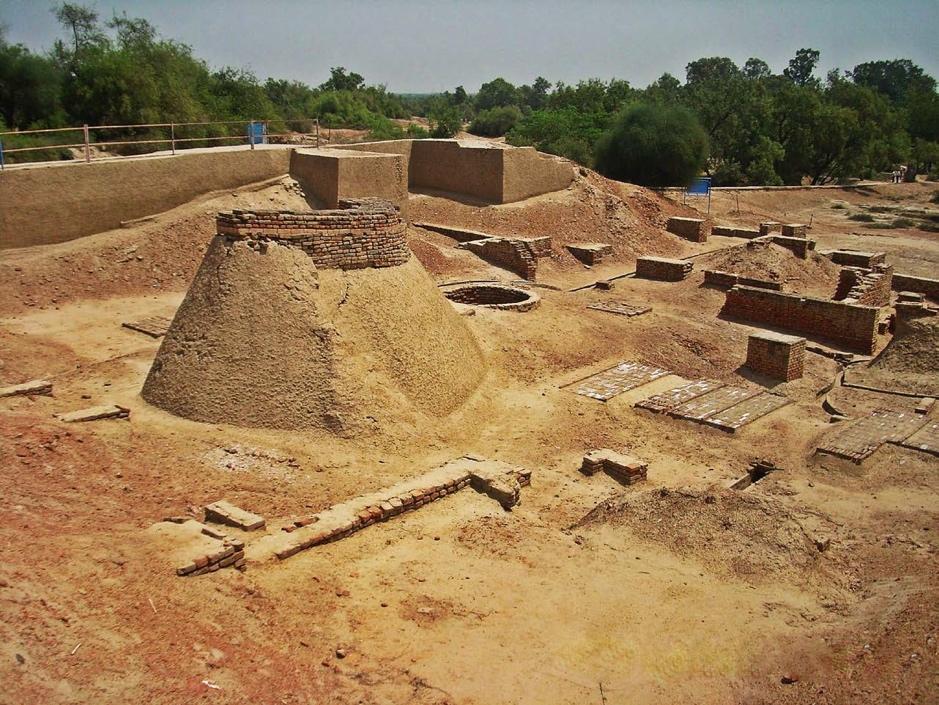

Our knowledge of the ancient world has been radically altered by impressive archaeological discoveries over the last two centuries. Prior to the twentieth century, for instance, historians believed that India’s history began in the second millennium BCE, when a people known as Indo-Aryans migrated into the Indian subcontinent and created a new civilization. Yet, even during the nineteenth century, British explorers and officials were curious about brick mounds dotting the landscape of northwest India, where Pakistan is today. A large one was located in a village named Harappa (see Figure 3.1). A British army engineer, Sir Alexander Cunningham, sensed its importance because he also found other artifacts among the bricks, such as a seal with an inscription. He was, therefore, quite dismayed that railway contractors were pilfering these bricks for ballast. When he became the director of Great Britain’s Archaeological Survey in 1872, he ordered protection for these ruins. But the excavation of Harappa did not begin until 1920, and neither the Archaeological Survey nor Indian archaeologists understood their significance until this time. Harappa, it turned out, was an ancient city dating back to the third millennium BCE and only one part of a much larger civilization sprawling over northwest India. With the discovery of this lost civilization, the timeline for India’s history was pushed back over one thousand years.

The Indus Valley Civilization (2600–1700 BCE) now stands at the beginning of India’s long history. Much like the states of ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt, the foundations for that history were established by Paleolithic foragers who migrated to and populated the region and then Neolithic agriculturalists who settled into villages. During the third millennium BCE, building on these foundations, urban centers emerged along the Indus River, along with other elements that contribute to making a civilization.

This civilization, however, faded away by 1700 BCE and was followed by a new stage in India’s history. While it declined, India saw waves of migration from the mountainous northwest by a people who referred to themselves as Aryans. The Aryans brought a distinctive language and way of life to the northern half of India and, after first migrating into the Punjab and Indus Valley, pushed east along the Ganges River and settled down into a life of farming and pastoralism. As they interacted with indigenous peoples, a new period in India’s history took shape. That period is known as the Vedic Age (1700–600 BCE).

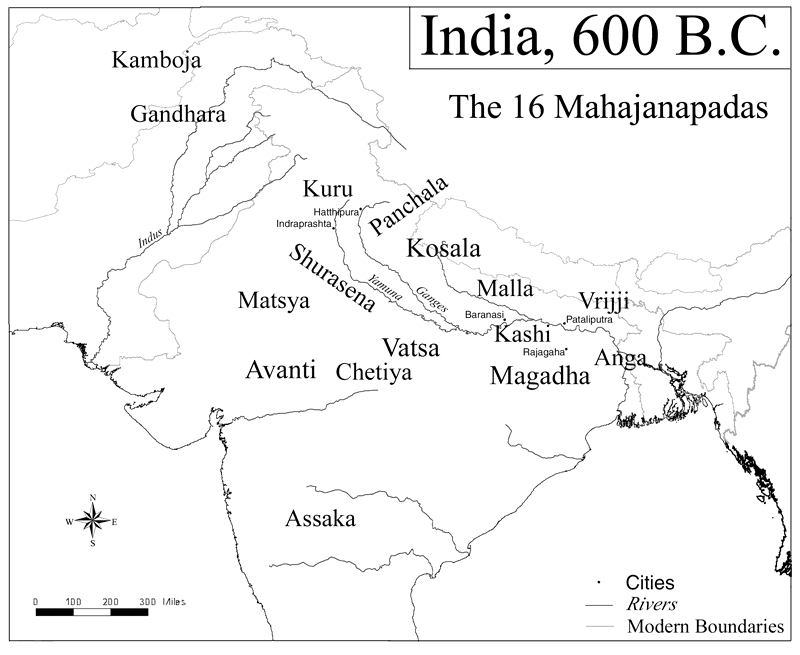

During the long course of the Vedic Age, states formed in northern India. The surplus from farming and pastoralism allowed people to engage in a multitude of other occupations and made for a lively trade. Villages thus grew in number, and some became towns. Consequently, there was a need for greater leadership, something that was provided by chieftains of the many Aryan clans. Over time, higher levels of political organization developed, and these chieftains became kings or the leaders of clan assemblies. By the end of the Vedic Age, northern India was divided up by sixteen major kingdoms and oligarchies.

The ensuing three centuries (c. 600–321 BCE) were a time of transition. These states fought with each other over territory. The most successful state was the one that could most effectively administer its land, mobilize its resources, and field the largest armies. That state was the kingdom of Magadha, which by the fourth century BCE had gained control of much of northern India along the Ganges River.

In 321 BCE, the last king of Magadha was overthrown by one of his subjects, Chandragupta Maurya, and a new period in India’s history began. Through war and diplomacy, he and his two successors established control over most of India, forging the first major empire in the history of South Asia: the Mauryan Empire (321–184 BCE). Chandragupta’s grandson, King Ashoka, ended the military conquests and sought to rule his land through Buddhist principles of non-violence and tolerance. But after his time, the empire rapidly declined, and India entered a new stage in its history.

After the Mauryan Empire fell, no one major power held control over a substantial part of India for five hundred years. Rather, from c. 200 BCE to 300 CE, India saw a fairly rapid turnover of numerous regional kingdoms. Some of these were located in northern India, along the Ganges River, but others grew in southern India for the first time. Also, some kingdoms emerged through foreign conquest. Outsiders in Central Asia and the Middle East saw India as a place of much wealth and sought to plunder it or rule it. Thus, throughout its history, India was repeatedly invaded by conquerors coming through mountain passes in the northwest. Many of these, like King Kanishka of the Kushan Empire (c. 100 CE), established notable kingdoms that extended from India into these neighboring regions from which they came.

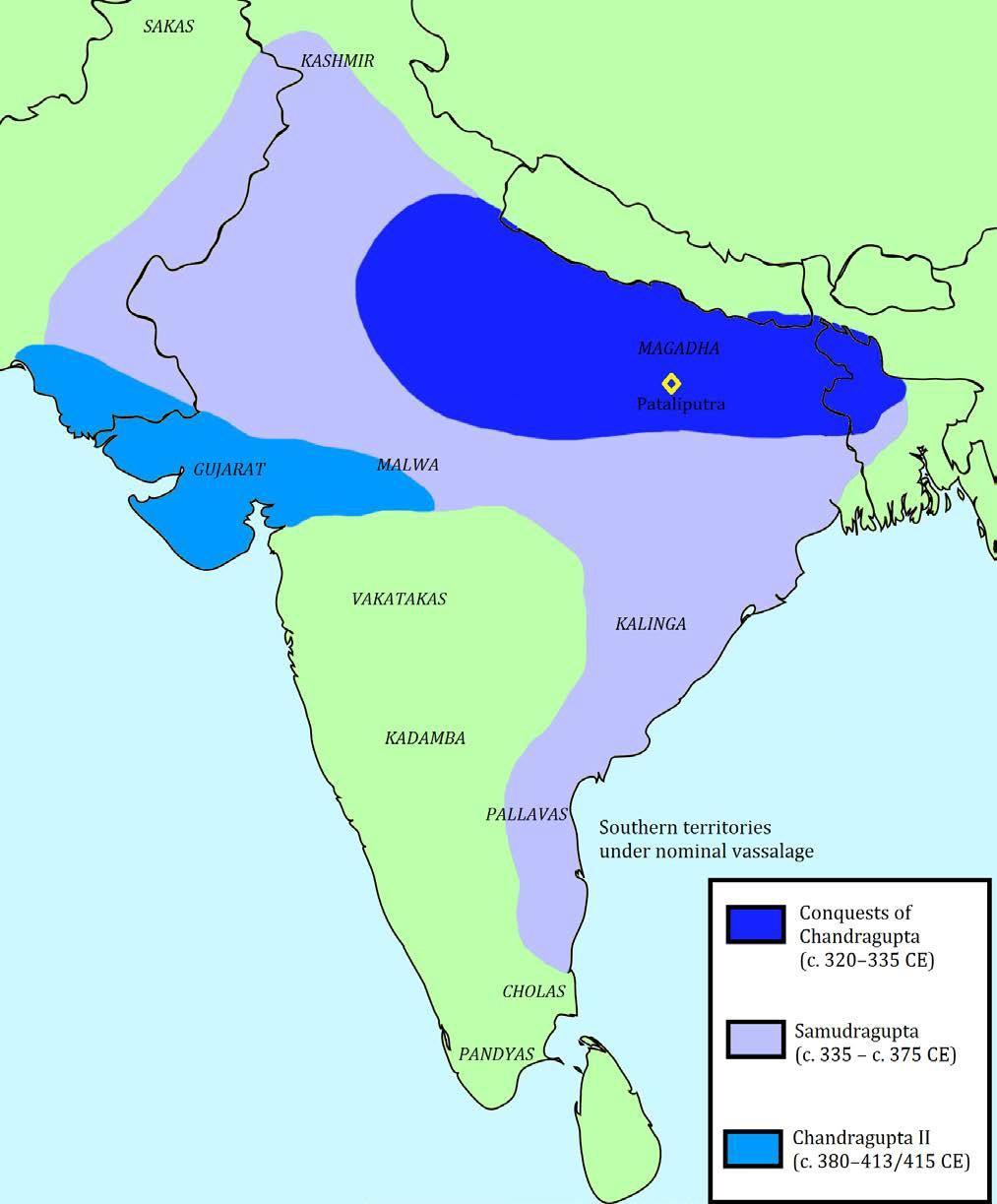

Even after 300 CE and up to the fifteenth century, India was never again unified for any length of time by one large empire. For that reason, historians highlight those kingdoms that became substantial regional powers and contributed in other important ways to India’s civilization. The period 300–600 CE, for instance, is often referred to as the Gupta period and classical age. The Guptas (c. 320–550) were rulers who forged an impressive empire in northern India. As their empire flourished, Indian intellectuals were also setting standards for excellence in the fields of art, architecture, literature, and science, in part because of Gupta patronage. But important kingdoms also developed in south India.

The last period covered in this chapter is early medieval India (c. 600–1300 CE). After the Gupta Empire, and during the following seven centuries, the pattern of fragmentation intensified, as numerous regional kingdoms large and small frequently turned over. Confronting such an unstable and fluid political scene, medieval kings granted land to loyal subordinate rulers and high officers of their courts. The resulting political and economic pattern is referred to as Indian feudalism. Also, kings put their greatness on display by waging war and building magnificent Hindu temples in their capital cities. And during the medieval period, a new political and religious force entered the Indian scene, when Muslim Arab and Turkic traders and conquerors arrived on the subcontinent.

This overview briefly summarizes major periods in India’s political history. But the history of a civilization consists of more than just rulers and states, which is why historians also pay close attention to social, cultural, and economic life every step of the way. This attention is especially important for India. Although the Asian subcontinent saw a long succession of kingdoms and empires and was usually divided up by several at any particular point in its history, peoples over time came to share some things in common. Socially, the peoples of India were largely organized by the caste system. Culturally, the peoples of India shared in the development of Hinduism and Buddhism, two major religious traditions that shaped people’s understanding of the world and their place in it. Finally, throughout the ancient and medieval periods, India flourished as a civilization because of its dynamic economy. The peoples of India shared in that too, and that meant they were linked in networks of trade and exchange not only with other parts of South Asia but also with neighboring regions of the Afro-Eurasian world.

3.3 QUESTIONS TO GUIDE YOUR READING

- How did the geography of South Asia (India) impact its history?

- What are the limits of our knowledge of the Harappan Civilization?

- How did kingdoms form during the Vedic Age?

- Describe the varna and caste systems.

- Explain the early historical origins and basic beliefs of Hinduism and Buddhism. How do these religious traditions change over time?

- How was the Mauryan Empire governed?

- How was India impacted by other regions of Afro-Eurasia, and how did it impact them?

- Why is the Gupta period sometimes described as a classical age?

- What are the characteristics of early medieval India?

- Explain the history of the formation of Muslim states in India.

3.4 KEY TERMS

- Arthashastra

- Aryabhata

- Ashoka (Mauryan Empire)

- Atman

- Ayurveda

- Bay of Bengal

- Bhagavad-Gita

- Brahman

- Brahmanism

- Caste and varna

- Chandragupta I (Gupta Empire)

- Chandragupta Maurya

- Chola Kingdom

- Coromandel Coast

- Deccan Plateau

- Delhi Sultanate

- Dharma (Buddhist and Hindu)

- Dharma Scriptures

- Four Noble Truths

- Ganges River

- Guilds

- Gupta Empire

- Harappan/Indus Valley Civilization

- Hindu Kush

- India

- Indian feudalism

- Indo-Europeans

- Indus River

- Indo-Gangetic Plain

- Kalidasa

- Kanishka

- Karma

- Kushan Kingdom

- Magadha

- Mahayana Buddhism

- Malabar Coast

- Mahmud of Ghazna

- Mehrgarh

- Mohenjo-Daro

- Pataliputra

- Punjab

- Ramayana

- Samudragupta

- Satavahana Kingdom

- Seals (Harappan/Indus Valley Civilization)

- Siddhartha Gautama/Buddha

- Sindh

- South Asia

- Sri Lanka

- Theravada Buddhism

- Transmigration

- Tributary overlordship

- Upanishads

- Vedic Age

3.5 WHAT IS INDIA? THE GEOGRAPHY OF SOUTH ASIA

India’s dynamic history, then, alternated between periods when the subcontinent was partially unified by empires and periods when it was composed of a shifting mosaic of regional states. This history was also impacted by influxes of migrants and invaders. In thinking about the reasons for these patterns, historians highlight the size of India and its diverse geography and peoples.

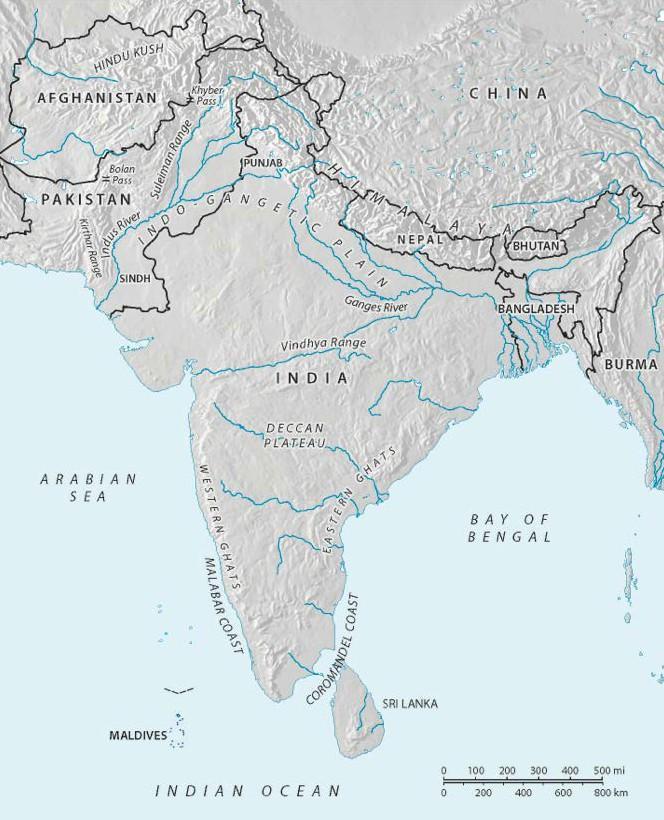

It is important to remember that “India” can mean different things. Today, India usually designates the nation-state of India (see Map 3.1). But modern India only formed in 1947 and includes much less territory than India did in ancient times. As a term, India was first invented by the ancient Greeks to refer to the Indus River and the lands and people beyond it. When used in this sense, India also includes today’s nation of Pakistan. In fact, for the purpose of studying earlier history, India can be thought of as the territory that includes at least seven countries today: India, Pakistan, Bhutan, Bangladesh, Nepal, Sri Lanka, and the Maldives. This territory is also referred to as South Asia or the Indian subcontinent.

The Indian subcontinent is where Indian civilization took shape. But that civilization was not created by one people, race, or ethnic group, and it doesn’t make sense to see India’s history as the history of one Indian people. Rather, the history of this region was shaped by a multitude of ethnic groups who spoke many different languages and lived and moved about on a diverse terrain suited to many different kinds of livelihood.

Large natural boundaries define the subcontinent. Mountain ranges ring the north, and bodies of water surround the rest. To the east lies the Bay of Bengal, to the south the Indian Ocean, and to the west the Arabian Sea. The largest mountain range is the Himalaya, which defines India’s northern and northeastern boundary. A subrange of the Himalaya—the Hindu Kush—sits at its western end, while a ridge running from north to south defines the eastern end, dividing India from China and mainland Southeast Asia. To the northwest, the Suleiman Range and Kirthar Range complete what might seem like impassable barriers. Yet, these ranges are punctuated by a few narrow passes that connect India to Central Asia and West Asia.

To the south of the mountain ranges lie the Indo-Gangetic Plain and the two great rivers of northern India that comprise it: the Indus River and the Ganges River. These rivers originate in the Himalaya and are regularly fed by snowmelt and monsoon rains. The Indus River, which is located in the northwest and drains into the Arabian Sea, can be divided into an upper and lower region. The region comprising the upper Indus and its many tributary rivers is called the Punjab, while the region surrounding the lower Indus is referred to as the Sindh. The Ganges River begins in the western Himalaya and flows southeast across northern India before draining into the Bay of Bengal. Because they could support large populations, the plains surrounding these river systems served as the heartland for India’s first major states and empires.

Peninsular India is also an important part of the story because over time great regional kingdoms also emerged in the south. The peninsula is divided from northern India by the Vindhya Mountains, to the south of which lies the Deccan Plateau. This arid plateau is bordered by two coastal ranges—the Western Ghats and Eastern Ghats, beyond which are narrow coastal plains, the Malabar Coast and the Coromandel Coast. This nearly 4600 miles of coastline is important to India’s history because it linked fishing and trading communities to the Indian Ocean and, therefore, the rest of Afro-Eurasia. Sri Lanka is an island located about thirty kilometers southeast of the southernmost tip of India and also served as an important conduit for trade and cultural contacts beyond India.

3.6 INDIA’S FIRST MAJOR CIVILIZATION: THE INDUS VALLEY CIVILIZATION (2600 BCE–1700 BCE)

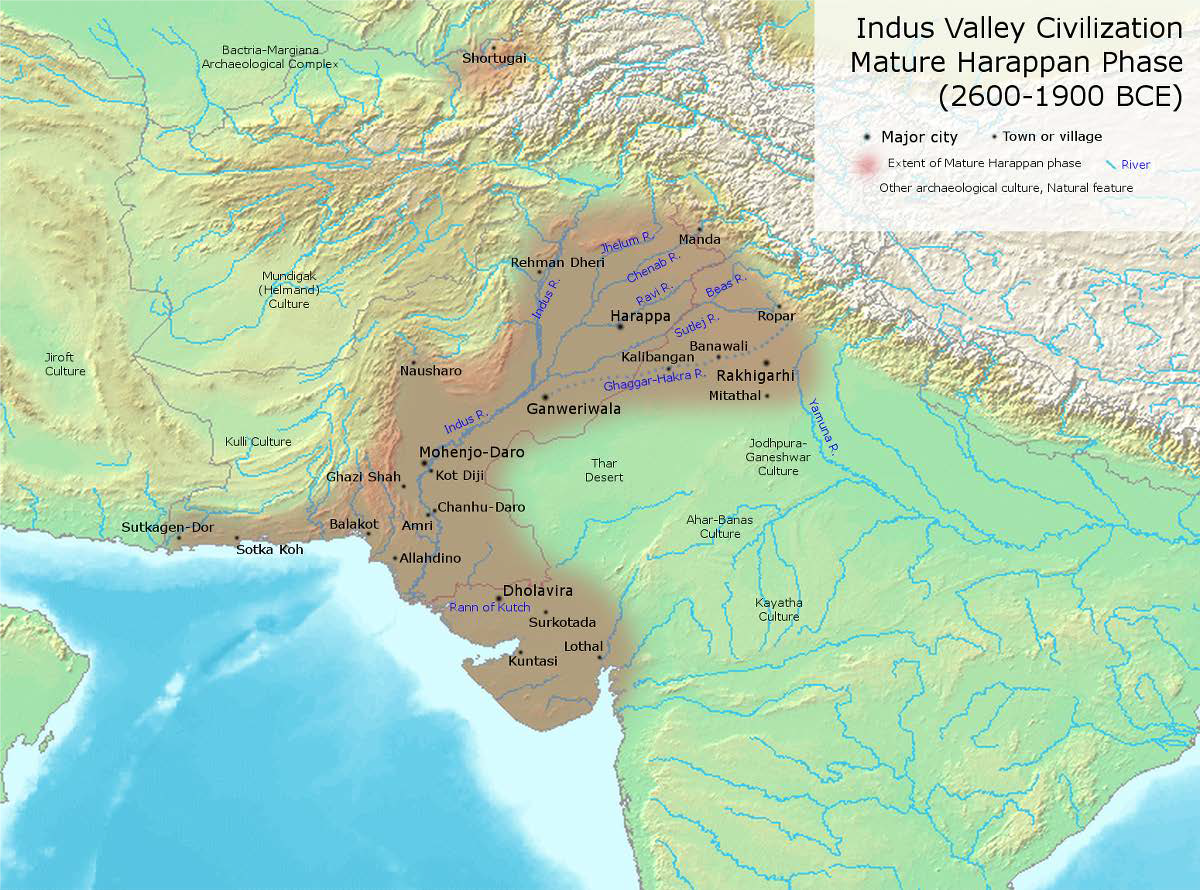

A century of archaeological work in India that began in 1920 revealed not only a lost civilization but also a massive one, surpassing in size other major early riverine civilizations of Afro-Eurasia, such as ancient Egypt and the Mesopotamian states. In an area spanning roughly a half million square miles, archaeologists have excavated thousands of settlements (see Map 3.2). These can be envisioned in a hierarchy based on size and sophistication. The top consists of five major cities of roughly 250 acres each. One of those is Harappa, and because it was excavated first, the entire civilization was named the Harappan Civilization. The bottom of the hierarchy consists of fifteen thousand smaller agricultural and craft villages of about 2.5 acres each, while between the top and bottom lie two tiers with several dozen towns ranging in size from 15 to 150 acres. Because the majority of these settlements were situated near the Indus River in the northwestern region of the subcontinent, this civilization is also called the Indus Valley Civilization.

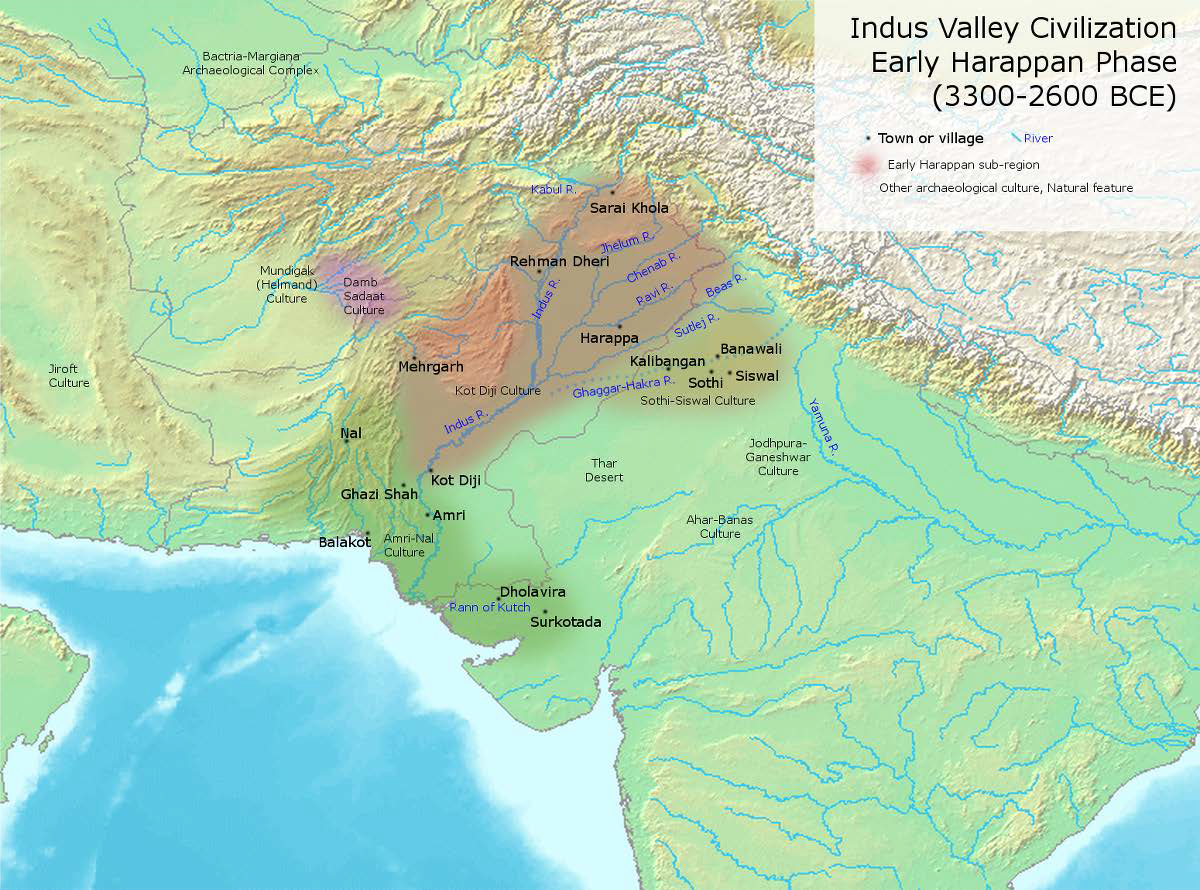

As with ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia, archaeologists have been able to sketch out how this civilization evolved out of the simpler agricultural villages of the Neolithic period. On the subcontinent, farming and the domestication of animals began c. 7000 BCE, about two thousand years after they did in the Fertile Crescent. To the west of the Indus River, along the foothills of Baluchistan, the remains of numerous small villages have been found that date back to this time (see Map 3.3). One of these is Mehrgarh. Here, villagers lived in simple mud-brick structures, grew barley and wheat, and raised cattle, sheep, and goats.

Over the course of the next three thousand years, similar Neolithic communities sprang up not only in northwest India but also in many other locations on the subcontinent. But it was to the west of the Indus River and then throughout neighboring fertile plains and valleys of the Punjab and Sindh that we see the transition to a more complex, urban-based civilization. Excavations throughout this region show a pattern of development whereby settlements start looking more like towns than villages: ground plans become larger, include the foundations of houses and streets, and are conveniently located by the most fertile land or places for trade. Similar artifacts spread over larger areas show that the local communities building these towns were becoming linked together in trade networks. Archaeologists date this transitional period when India was on the verge of its first civilization from 5000 to 2600 BCE. The mature phase, with its full-blown cities, begins from 2600 BCE, roughly four centuries after the Sumerian city-states blossomed and Egypt was unified under one kingdom.

The ruins of Mohenjo-Daro and other Indus cities dating to this mature phase suggest a vibrant society thriving in competently planned and managed urban areas. Some of the principal purposes of these urban settlements included coordinating the distribution of local surplus resources, obtaining desired goods from more distant places, and turning raw materials into commodities for trade. Mohenjo-Daro, for instance, was located along the lower reaches of the Indus (see Figure 3.2). That meant it was conveniently built amidst an abundance of resources: fertile floodplains for agriculture, pasture for grazing domesticated animals, and waters for fishing and fowling. The city itself consisted of several mounds—elevated areas upon which structures and roads were built. A larger mound served as a core, fortified area where public functions likely took place. It contained a wall and large buildings, including what archaeologists call a Great Bath and Great Hall. Other mounds were the location of the residential and commercial sectors of the city. Major avenues laid out on a grid created city blocks. Within a block, multistory dwellings opening up to interior courtyards were constructed out of mud bricks or bricks baked in kilns. Particular attention was paid to public sanitation. Residences had not only private wells and baths but also toilets drained by earthenware pipes that ushered the sewage into covered drains located under the streets.

Farmers and pastoralists brought their grain and stock to the city for trade or to place it in warehouses managed by the authorities. Laborers dug the wells and collected trash from rectangular bins sitting beneath rubbish chutes. Craftsmen worked copper and tin into bronze tools, fired ceramics, and manufactured jewelry and beads out of gold, copper, semi-precious stones, and ivory. Merchants traveling near and far carried raw materials and finished goods by bullock carts or boats to the dozens of towns and cities throughout the region.

Some goods also went to foreign lands. Harappan cities located along the coast of the Arabian Sea engaged in coastal shipping that brought goods as far as the Persian Gulf and the delta of the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers. In Mesopotamian city-states, Harappan seals and beads have been found, and Mesopotamian sources speak of a certain place called “Meluhha,” a land with ivory, gold, and lapis lazuli. Cities like Mohenjo-Daro were linked in networks of exchange extending in every direction.

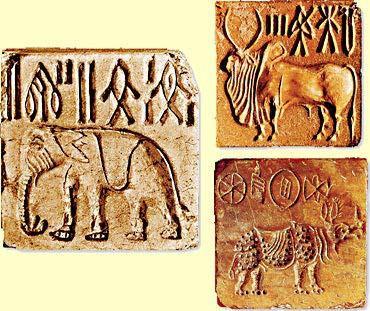

But unlike ancient Egypt and Sumer, this civilization has not yet provided sources we can read, and this poses major problems of interpretation—although over four thousand inscribed objects with at least four hundred different signs recurring in various frequencies have been found on clay, copper tablets, and small, square seals excavated primarily at the major cities (see Figure 3.3). But the heroic efforts of philologists to decipher the language have failed to yield results. Thus, some historians call this civilization proto-historic, distinguishing it from both prehistoric cultures that have no writing and historic ones with written sources that we can read.

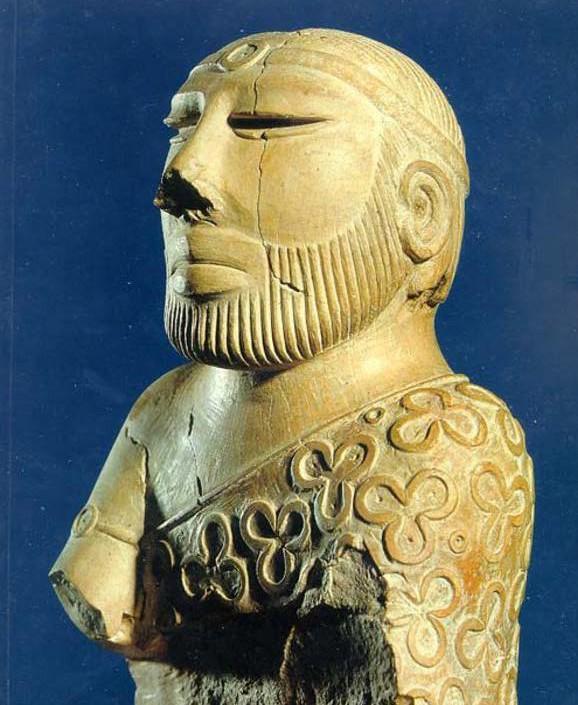

This proto-historical state of the evidence leaves many questions concerning Harappan people’s political organization and beliefs unanswered. On the one hand, much uniformity in the archaeological record across the region suggests coordination in planning—cities and towns were similarly designed, fired bricks had the same dimensions, and weights were standardized. On the other hand, the ruins lack structures that can be clearly identified as palaces, temples, or large tombs. In other words, there is little evidence for either a central political authority ruling over an empire or for independent city-states. One intriguing artifact found in Mohenjo-Daro is a small sculpture of a bearded man made of soapstone (see Figure 3.4). The dignified appearance suggests he may have been a priest or king, or even both. Perhaps he and other priests purified themselves in the Great Bath for ritual purposes. Yet, this is purely speculation, as the sculpture is unique. He may also have been a powerful landowner or wealthy merchant who met with others of a similar status in assemblies convened in the Great Hall of the citadel. Perhaps local assemblies of just such elites governed each city.

Religious beliefs are also difficult to determine. Again, some of the principal evidence consists of small artifacts such as figurines and the square seals. The seals were carved out of a soft stone called steatite and then fired so they would harden. They contain images of animals and humans, typically with writing above. Mostly, they were used to imprint the identity of a merchant or authorities on goods. However, some of the images may have had religious significance. For example, hundreds of “unicorn seals” display images of a mythical animal that resembles a species of cattle (see Figure 3.5). These cattle are usually placed over an object variously interpreted as a trough or altar. Perhaps these were symbols of deities or animals used for sacrificial rituals. Equally as interesting are the numerous female clay figurines. These may have been used for fertility rituals or to pay homage to a goddess (see Figure 3.6).

The decline of the Harappan Civilization set in from 1900 BCE and was complete two hundred years later. Stated simply, the towns and cities and their lively trade networks faded away, and the region reverted to rural conditions. Likely causes include geologic, climatic, and environmental factors. Movement by tectonic plates may have led to earthquakes, flooding, and shifts in the course of the Indus. Less rainfall and deforestation may have degraded the environment’s suitability for farming. All of these factors would have impacted the food supply. Consequently, urban areas and the civilization they supported were slowly starved out of existence.

3.7 THE LONG VEDIC AGE (1700–600 BCE)

By 1700 BCE, the Harappan Civilization had collapsed. In northwest India, scattered village communities engaging in agriculture and pastoralism replaced the dense and more highly populated network of cities, towns, and villages of the third millennium. The rest of northern India too (including the Ganges River), as well as the entire subcontinent, were similarly dotted with Neolithic communities of farmers and herders. That is what the archaeological record demonstrates.

The next stage in India’s history is the Vedic Age (1700–600 BCE). This period is named after a set of religious texts composed during these centuries called the Vedas. The people who composed them are known as the Vedic peoples and Indo-Aryans. They were not originally from India but rather came as migrants traveling to the subcontinent via mountain passes located in Afghanistan and Pakistan. The Aryans first settled in the Punjab, but then they pushed east along the Ganges, eventually impressing their way of life, language, and religious beliefs upon much of northern India. The course of India’s history was completely changed during this period. By the end of the Vedic Age, numerous states had emerged, and Hinduism and the varna social system were beginning to take shape.

3.7.1 The Early Aryan Settlement of Northern India (1700–1000 BCE)

The early history of the Vedic Age offers the historian little primary source material. For example, for the first half of the Vedic Age (1700–1000 BCE), we are largely limited to archaeological sites and one major text called the Rig Veda. This is the first of four Vedas. It consists of 1028 hymns addressed to the Vedic peoples’ pantheon of gods. But it wasn’t actually written down until after 500 BCE. Rather, from as early as the beginning of the second millennium BCE, these hymns were orally composed and transmitted by Aryan poetseers, eventually becoming the preserve of a few priestly clans who utilized them for the specific religious function of pleasing higher powers. Thus, these hymns only offer certain kinds of information. Yet, despite these limits, historians have been able to sketch out the Aryans’ way of life in these early centuries as well as make solid arguments about how they came to India.

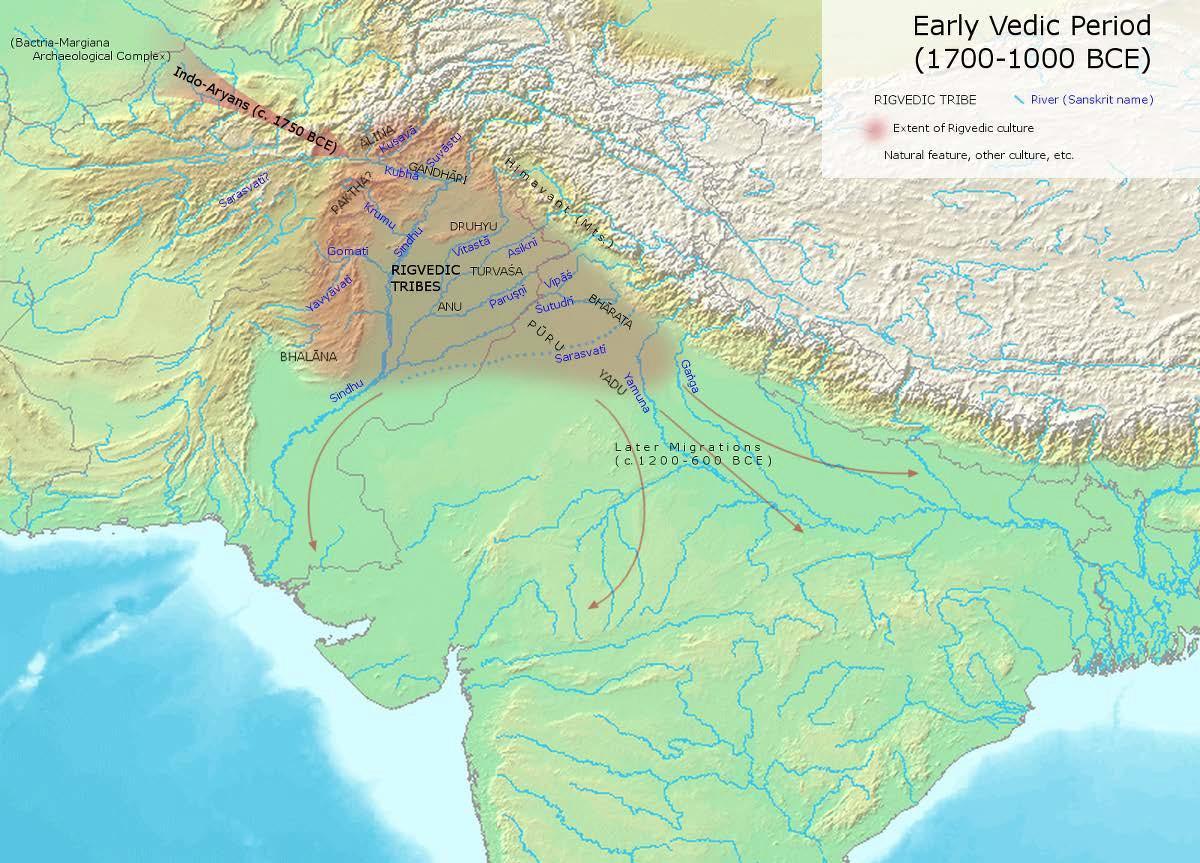

The Indo-Aryans were pastoralists who migrated to India in waves beginning c. 1700 BCE (see Map 3.4). They referred to themselves as Aryans, a term meaning “noble” or “respectable.” They spoke Sanskrit and used it to transmit their sacred hymns. At first, in search of land, they settled along the hills and plains of the upper reaches of the Indus River and its tributaries, bringing with them their pastoral and farming way of life. In their hymns, the Aryans beseech the gods to bless them with cattle, bounteous harvests, rain, friends, wealth, fame, and sons. From these, it is clear that herding was the principal occupation, and cows were especially prized. But the Aryans also farmed, as apparent in hymns that speak of plough teams and the cutting and threshing of grain.

During these early centuries, led by their pastoral chiefs, some Aryans retained a semi-nomadic way of life, living in temporary dwellings and then moving about with their herds or migrating further. Others settled down in villages. In both cases, kinship was especially valued. At the simplest level, society consisted of extended families of three generations. Fathers were expected to lead the family as patriarchal heads, while sons were expected to care for the herds, bring honor through success in battle, and sacrifice for the well-being of their fathers’ souls after death. They also inherited the property and family name. This suggests that, as is so often the case for ancient societies, men were dominant and women were subordinate. Yet, women’s roles weren’t as rigidly defined as they would be in later times, and they had some choice in marriage and could remarry.

Several extended families, in turn, made up clans, and the members of a clan shared land and herds. Groups of larger clans also constituted tribes. The Vedas speak of rajas who, at this point, are best understood as clan or tribal chieftains. These men protected their people and led in times of battle, for the clans and tribes fought with each other and with the indigenous villagers living in the northwest prior to the Aryan migrations. In times of war, these chiefs would rely on priests who ensured the support of the gods by reciting hymns and sacrificing to them. At assemblies of kinsmen and other wealthy and worthy men from the clan, the rajas distributed war booty. Sudas, for example, was the chief of the Bharata clan. After settling in the Punjab, the Bharatas were attacked by neighboring clan confederacies, but drawing on his skills in chariot warfare and the support of priests, Sudas successfully fought them off.

More than anything else, the Rig Veda reveals the Aryans’ religious ideas. For them, the universe was composed of the sky, earth, and netherworld. These realms were populated by a host of divinities and demons responsible for the good and evil and order and disorder afflicting the human world. Although one Vedic hymn gives a total of thirty-three gods, many more are mentioned. That means early Vedic religion was polytheistic. These human-like powers lying behind all those natural phenomena so close to a people living out on the plains were associated with the forces of light, good, and order. By chanting hymns to them and sacrificing in the correct way, the Aryan priests might secure blessings for the people or prevent the demons and spirits on earth from causing sickness and death. They might also ensure that the souls of the dead would successfully reach the netherworld, where the spirits of righteous Fathers feasted with King Yama, the first man to die.

Approaching the gods required neither temples nor images. Rather, a fire was lit in a specially prepared sacrificial altar. This might take place in a home when the family patriarch was hoping for a son or on an open plot of land when the clan chieftain wished to secure the welfare of his people. Priests were called in to perform the ceremony. They would imbibe a hallucinogenic beverage squeezed from a plant of uncertain identity and chant hymns while oblations of butter, fruit, and meat were placed in the fire. The gods, it was believed, would descend onto grass strewn about for them and could partake of the offerings once they were transmuted by the fire.

Indra was among the most beloved of the Vedic gods. As a god of war and storm, and as king of the gods, Indra exemplified traits men sought to embody in their lives. He is a great warrior who smites demons and enemies but who also provides generously for the weak. Agni, another favorite, was the god of fire and the household hearth. Agni summons the gods to the sacrifice and, as intermediary between gods and humans, brings the sacrificial offering to them.

3.7.2 The Origins of the Aryan People and the Indo-European Hypothesis

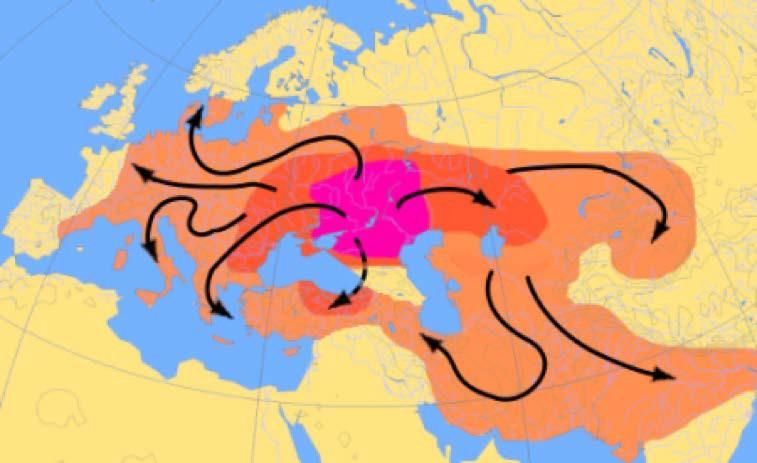

Because the Aryans came to India as migrating pastoralists from mountainous regions to the northwest of the Indian subcontinent, historians have sought to understand their origins. Sanskrit has provided important clues because it contains features similar to languages spoken at some point in Europe, Iran, and Central Asia. For example, although they are vastly different languages, Latin, Persian, and Sanskrit share similar sounds, vocabulary, and grammar.

On the basis of these shared traits, linguists have constructed a kind of family tree that shows the historical relationship between these languages. Sanskrit belongs to a group of languages used in northern India called Indo-Aryan. These languages are closely related to languages used throughout history in neighboring Iran. Together, all of these are called the Indo-Iranian language group. This language group is in turn one of nine branches of related language groups comprising the Indo-European language family.

Linguists assume these distantly-related languages share a common ancestor. They label that ancestral language proto-Indo-European and the people who spoke it Indo-Europeans. They posit a scenario whereby, in stages and over time, groups of these peoples migrated from their homeland to neighboring areas and settled down. Since this process happened over the course of many centuries and involved much interaction with other peoples along the way, the ancestral language evolved into many different ones while retaining some of the original features.

One question, then, is the location of this homeland and the history of the peoples who spoke these languages as they changed. Many places have been proposed, but at present, the most widely accepted scenario puts this homeland in the steppe lands of southern Russia, just to the north of the Black Sea and Caspian Sea (see Map 3.5).

Evidence from archaeological sites suggests that during the third millennium, an Indo-European people lived in this region as semi-nomadic pastoralists. They were likely the first to domesticate the horse and also improved the chariot by adding lighter, spoked wheels. They lived in tribes made up of extended families and worshipped numerous sky gods by offering sacrifices in fire altars. At some point during this millennium and over the course of several centuries, groups of these peoples left their homeland and migrated south to the Iranian Plateau. By 2000 BCE, Indo-Iranian-speaking pastoralists were living on the Iranian Plateau and in Afghanistan. Some among these evolved into the Indo-Aryan speakers living to the northwest of the Indus. It is these peoples that began to arrive in the Punjab from c. 1700 BCE, with their Vedic religion, kinship-based social order, and pastoral and farming way of life.

3.7.3 The Later Vedic Age (1000–600 BCE)

During the early centuries of the Vedic Age, the world of the Aryan tribes was the rural setting of the Punjab. Some settlers, however, migrated east to the upper reaches of the Ganges River, setting the stage for the next period in India’s history, the later Vedic Age. The later Vedic Age differs from the early Vedic Age in that during these centuries, lands along the Ganges River were colonized by the Aryans, and their political, economic, social, and religious life became more complex.

Over the course of these four centuries, Aryan tribes, with horses harnessed to chariots and wagons drawn by oxen, drove their herds east, migrating along and colonizing the plains surrounding the Ganges. Historians debate whether this happened through conquest and warfare or intermittent migration led by traders and people seeking land and opportunity. Regardless, by 600 BCE, the Aryans had reached the lower reaches of the Ganges and as far south as the Vindhya Range and the Deccan Plateau. Most of northern India would therefore be shaped by the Aryan way of life. But in addition, as they moved into these areas, the Aryans encountered indigenous peoples and interacted with them, eventually imposing their way of life on them but also adopting many elements of their languages and customs.

During this time, agriculture became more important and occupations more diverse. As the lands were cleared, village communities formed. Two new resources made farming more productive: iron tools and rice. Implements such as iron axes and ploughs made clearing wilderness and sowing fields easier, and rice paddy agriculture produced more calories per unit of land. Consequently, the population began to grow, and people could more easily engage in other occupations. By the end of this period, the earliest towns had started to form.

Political changes accompanied economic developments. Looking ahead at sixth-century northern India, the landscape was dominated by kingdoms and oligarchies. That raises the question of the origins of these two different kinds of states, where different types of central authority formally governed a defined territory. Clearly, these states began to emerge during the later Vedic Age, especially after the eighth century.

Prior to this state formation, chiefs (rajas) and their assemblies, with the assistance of priests, saw to the well-being of their clans. This clan-based method of governing persisted and evolved into oligarchies. As the Aryans colonized new territory, clans or confederacies of clans would claim it as their possession and name it after the ruling family. The heads of clan families or chiefs of each clan in a confederacy then jointly governed the territory by convening periodically in assembly halls. A smaller group of leaders managed the deliberations and voting and carried out the tasks of day-to-day governing. These kinds of states have been called oligarchies because the heads of the most powerful families governed. They have also been called republics because these elites governed by assembly.

But in other territories, clan chiefs became kings. These kings elevated themselves over kinsmen and the assemblies and served as the pivot of an embryonic administrative system. Their chief priests conducted grand rituals that demonstrated the king’s special relation with the gods, putting the people in awe of him and giving them the sense that they would be protected. Treasurers managed the obligatory gifts kings expected in return. Most importantly, kingship became hereditary, and dynasties started to rule (see Map 3.6).

Society changed too. In earlier times, Aryan society was organized as a fluid three-class social structure consisting of priests, warriors, and commoners. But during the later Vedic Age, this social structure became more hierarchical and rigid. A system for classifying people based on broad occupational categories was developed by the religious and political leaders in society. These categories are known as varnas, and there were four of them: Brahmins, Kshatriya, Vaishya, and Shudra. The Brahmins were the priests, whose duty was to memorize and orally transmit the Vedas and perform sacrifices so as to maintain good relations with the gods. The Kshatriya were the chiefs and warriors, whose duty was to govern well and fight. The Vaishya were commoners who traded and farmed. They were responsible for society’s material prosperity. The Shudras were servants who labored for others, usually as artisans or by performing menial tasks.

Varnas became hereditary social classes. That means a person was born into one of these and usually remained there for life, pursuing an occupation included in and marrying someone belonging to that varna. Varna has also been translated as ritual status. Your varna determined how pure or polluted you were and thus what level of participation in rituals you would be allowed and also who you could associate with. Varna thus defined a social hierarchy. The Brahmins were the purest and most honored. Warriors were respected for their leadership and supported the Brahmins, who affirmed their authority by carrying out royal ceremonies. Together, they dominated society. The Shudras (servants) were the most polluted and could not participate in any sacrifice or speak freely to members of other varnas. Over time, this way of organizing society came to be viewed as normal and natural.

During the later Vedic Age, the religion of the Aryans also developed in new directions. As one of the world’s major religious traditions, Hinduism is multi-faceted and contains many layers of historical development. The earliest layer is called Brahmanism. Brahmanism begins with the Rig Veda, which presents a universe controlled by a host of divinities. During the early Vedic Age, the Aryans explained the world through myths about these higher powers, and their priests sought to influence them through sacrificial ceremonies.

This early layer persisted and became even more elaborate. Three new Vedas were added to the Rig Veda, as well as two sets of texts called Brahmanas and Upanishads. Combined, this literature, which was composed in Sanskrit, constituted the full Vedic corpus.

The Brahmins weren’t content with the 1028 hymns of the Rig Veda. Later Vedas set the hymns to music, added prose formulas that were to be uttered in the course of sacrificing to the divinities, and offered spells and incantations for achieving such goals as warding off disease and winning a battle. The Brahmanas were primarily handbooks of ritual for the Brahmins. They explained the meaning of the sacrifices and how to carry them out. Clearly, the Brahmins were becoming ever more conscious of their role in keeping the universe in good working order by pleasing and assisting the gods and consecrating kings. Their sacrificial observances became all the more elaborate and an essential component of good kingship.

The Upanishads, however, added an entirely new set of ideas. The title means “sitting near” and points to a setting where sages conveyed spiritual insights to students through dialogue, stories, and analogies. The Upanishads are records of what was taught and discussed, the earliest dating to the eighth and seventh centuries BCE. These sages were likely hermits and wanderers who felt spiritually dissatisfied with the mythological and ritualistic approach of Brahmanism. Rather, they sought deeper insight into the nature of reality, the origins of the universe, and the human condition. The concepts that appear throughout these records of the outcome of their search are brahman (not to be confused with Brahmins), atman, transmigration, and karma.

According to these sages, human beings face a predicament. The universe they live in is created and destroyed repeatedly over the course of immense cycles of time, and humans wander through it in an endless succession of deaths and rebirths. This wandering is known as transmigration, a process that isn’t random but rather determined by the law of karma. According to this law, good acts bring a better rebirth, and bad acts a worse one. It may not happen in this lifetime, but one day virtue will be rewarded and evil punished.

Ultimately, however, the goal is to be liberated from the cycle of death and rebirth. According to Hindu traditions, the Upanishads reflect spiritual knowledge that was revealed to sages who undertook an inward journey through withdrawal from the world and meditation. What they discovered is that one divine reality underlies the universe. They called this ultimate reality brahman. They also discovered that deep within the heart of each person lies the eternal soul. They called this soul atman. Through quieting the mind and inquiry, the individual can discover atman and its identity with brahman: the soul is the divine reality. That is how a person is liberated from the illusion of endless wandering.

In conclusion, by the end of the Vedic Age, northern India had undergone immense changes. An Aryan civilization emerged and spread across the Indo-Gangetic Plains. This civilization was characterized by the Brahmins’ religion (Brahmanism), the use of Sanskrit, and the varna social system. The simpler rural life of the clans of earlier times was giving way to the formation of states, and new religious ideas were being added to the evolving tradition known today as Hinduism.

3.8 TRANSITION TO EMPIRE: STATES, CITIES, AND NEW RELIGIONS (600 TO 321 BCE)

The sixth century begins a transitional period in India’s history marked by important developments. Some of these bring to fruition processes that gained momentum during the late Vedic Age. Out of the hazy formative stage of state development, sixteen powerful kingdoms and oligarchies emerged. By the end of this period, one will dominate. Accompanying their emergence, India entered a second stage of urbanization, as towns and cities became a prominent feature of northern India. Other developments were newer. The caste system took shape as an institution, giving Indian society one of its most distinctive traits. Lastly, new religious ideas were put forward that challenged the dominance of Brahmanism.

3.8.1 States and Cities

The kingdom of Magadha became the most powerful among the sixteen states that dominated this transitional period, but only over time. At the outset, it was just one of eleven located up and down the Ganges River (see Map 3.7). The rest were established in the older northwest or central India. In general, larger kingdoms dominated the Ganges basin, while smaller clan-based states thrived on the periphery. They all fought with each other over land and resources, making this a time of war and shifting alliances.

The victors were the states that could field the largest armies. To do so, rulers had to mobilize the resources of their realms. The Magadhan kings did this most effectively. Expansion began in 545 BCE under King Bimbisara. His kingdom was small, but its location to the south of the lower reaches of the Ganges River gave it access to fertile plains, iron ore, timber, and elephants. Governing from his inland fortress at Rajagriha, Bimbisara built an administration to extract these resources and used them to form a powerful military. After concluding marriage alliances with states to the north and west, he attacked and defeated the kingdom of Anga to the east. His son Ajatashatru, after killing his father, broke those alliances and waged war on the Kosala Kingdom and the Vrijji Confederacy. Succeeding kings of this and two more Magadhan dynasties continued to conquer neighboring states down to 321 BCE, thus forging an empire. But its reach was largely limited to the middle and lower reaches of the Ganges River.

To the northwest, external powers gained control. As we have seen, the mountain ranges defining that boundary contain passes permitting the movement of peoples. This made the northwest a crossroads, and at times, the peoples crossing through were the armies of rulers who sought to control the riches of India. Outside powers located in Afghanistan, Iran, or beyond might extend political control into the subcontinent, making part of it a component in a larger empire.

One example is the Persian Empire (see Chapter 5). During the sixth century, two kings, Cyrus the Great and Darius I, made this empire the largest in its time. From their capitals on the Iranian Plateau, they extended control as far as the Indus River, incorporating parts of northwest India as provinces of the Persian Empire. Another example is Alexander the Great (also see Chapter 5). Alexander was the king of Macedon, a Greek state. After compelling other Greeks to follow him, he attacked the Persian Empire, defeating it in 331 BCE. That campaign took his forces all the way to mountain ranges bordering India. Desiring to find the end of the known world and informed of the riches of India, Alexander took his army through the Khyber Pass and overran a number of small states and cities located in the Punjab. But to Alexander’s dismay, his soldiers refused to go any further, forcing him to turn back. They were exhausted from years of campaigning far from home and discouraged by news of powerful Indian states to the east. One of those was the kingdom of Magadha.

Magadha’s first capital—Rajagriha—is one of many cities and towns with ruins dating back to this transitional period. Urban centers were sparse during the Vedic Age but now blossomed, much like they did during the mature phase of the Harappan Civilization. Similar processes were at work. As more forests were cleared and marshes drained, the agricultural economy of the Ganges basin produced ever more surplus food. The population grew, enabling more people to move into towns and engage in other occupations as craftsmen, artisans, and traders. Kings encouraged this economic growth as its revenue enriched their treasuries. Caravans of ox-drawn carts or boats laden with goods traveling from state to state could expect to encounter the king’s customs officials and pay tolls. So important were rivers to accessing these trade networks that the Magadhan kings moved their capital to Pataliputra, a port town located on the Ganges (see Map 3.7). Thus, it developed as a hub of both political power and economic exchange. Most towns and cities began as one or the other, or as places of pilgrimage.

3.8.2 The Caste System

As the population of northern India rose and the landscape was dotted with more villages, towns, and cities, society became more complex. The social life of a Brahmin priest who served the king differed from that of a blacksmith who belonged to a town guild, a rich businessman residing in style in a city, a wealthy property owner, or a poor agricultural laborer living in a village. Thus, the social identity of each member of society differed.

In ancient India, one measure of identity and the way people imagined their social life and how they fit together with others was the varna system of four social classes. Another was caste. Like the varnas, castes were hereditary social classifications; unlike them, they were far more distinct social groups. The four-fold varna system was more theoretical and important for establishing clearly who the powerful spiritual and political elites in society were: the Brahmins and Kshatriya. But others were more conscious of their caste. There were thousands of these, and each was defined by occupation, residence, marriage, customs, and language. In other words, because “I” was born into such-and-such a caste, my role in society is to perform this kind of work. “I” will be largely confined to interacting with and marrying members of this same group. Our caste members reside in this area, speak this language, hold these beliefs, and are governed by this assembly of elders. “I” will also be well aware of who belongs to other castes and whether or not “I” am of a higher or lower status in relation to them, or more or less pure. On that basis, “I” may or may not be able, for instance, to dine with them. That is how caste defined an individual’s life.

The lowest castes were the untouchables. These were peoples who engaged in occupations considered highly impure, usually because they were associated with taking life; such occupations include corpse removers, cremators, and sweepers. So those who practiced such occupations were despised and pushed to the margins of society. Because members of higher castes believed touching or seeing them was polluting, untouchables were forced to live outside villages and towns, in separate settlements.

3.8.3 The Challenge to Brahmanism: Buddhism

During this time of transition, some individuals became dissatisfied with life and chose to leave the everyday world behind. Much like the sages of the Upanishads, these renunciants, as they were known, were people who chose to renounce social life and material things in order that they might gain deeper insight into the meaning of life. Some of them altogether rejected Brahmanism and established their own belief systems. The most renowned example is Siddhartha Gautama (c. 563–480 BCE), who is otherwise known as the Buddha.

Buddha means “Enlightened One” or “Awakened One,” implying that the Buddha was at one time spiritually asleep but at some point woke up and attained insight into the truth regarding the human condition. His life story is therefore very important to Buddhists, people who follow the teachings of the Buddha.

Siddhartha was born a prince, son to the chieftain of Shakya, a clan-based state located at the foothills of the Himalaya in northern India. His father wished for him to be a ruler like himself, but Siddhartha went in a different direction. At twenty-nine, after marrying and having a son, he left home. Legends attribute this departure to his having encountered an old man, a sick man, a corpse, and a wandering renunciant while out on an excursion. Aging, sickness, and death posed the question of suffering for Siddhartha, leading him to pursue spiritual insight. For years, he sought instruction from other wanderers and experimented with their techniques for liberating the self from suffering through meditation and asceticism. But he failed to obtain the answers he sought.

Then, one day, while seated beneath a tree meditating for an extended period of time, a deepening calm descended upon Siddhartha, and he experienced nirvana. He also obtained insight into the reasons for human suffering and what was needful to end it. This insight was at the heart of his teachings for the remaining forty-five years of his life. During that time, he traveled around northern India teaching his dharma—his religious ideas and practices—and gained a following of students.

The principal teaching of the Buddha, presented at his first sermon, is called the Four Noble Truths. The first is the noble truth of suffering. Based on his own experiences, the Buddha concluded that life is characterized by suffering not only in an obvious physical and mental sense but also because everything that promises pleasure and happiness is ultimately unsatisfactory and impermanent. The second noble truth states that the origin of suffering is an unquenchable thirst. People are always thirsting for something more, making for a life of restlessness with no end in sight. The third noble truth is that there is a cure for this thirst and the suffering it brings: nirvana. Nirvana means “blowing out,” implying extinction of the thirst and the end of suffering. No longer striving to quell the restlessness with temporary enjoyments, people can awaken to “the city of nirvana, the place of highest happiness, peaceful, lovely, without suffering, without fear, without sickness, free from old age and death.”[1] The fourth noble truth is the Eightfold Path, a set of practices that leads the individual to this liberating knowledge. The Buddha taught that through a program of study of Buddhist teachings (right understanding, right attitude), moral conduct (right speech, right action, right livelihood), and meditation (right effort, right concentration, right mindfulness), anyone could become a Buddha. Everyone has the potential to awaken, but each must rely on his or her own determination.

After the Buddha died c. 480 BCE, his students established monastic communities known as the Buddhist sangha. Regardless of their varna or caste, both men and women could choose to leave home and enter a monastery as a monk or nun. They would shave their heads, wear ochre-colored robes, and vow to take refuge in the Buddha, dharma, and sangha. Doing so meant following the example of the Buddha and his teachings on morality and meditation, as well as living a simple life with like-minded others in pursuit of nirvana and an end to suffering.

3.9 THE MAURYAN EMPIRE (321–184 BCE)

The kingdom of Magadha was the most powerful state in India when the Nanda Dynasty came to power in 364 BCE. Nine Nanda kings made it even greater by improving methods of tax collection and administration, funding irrigation projects and canal building, and maintaining an impressive army of infantry, cavalry, elephants, and chariots.

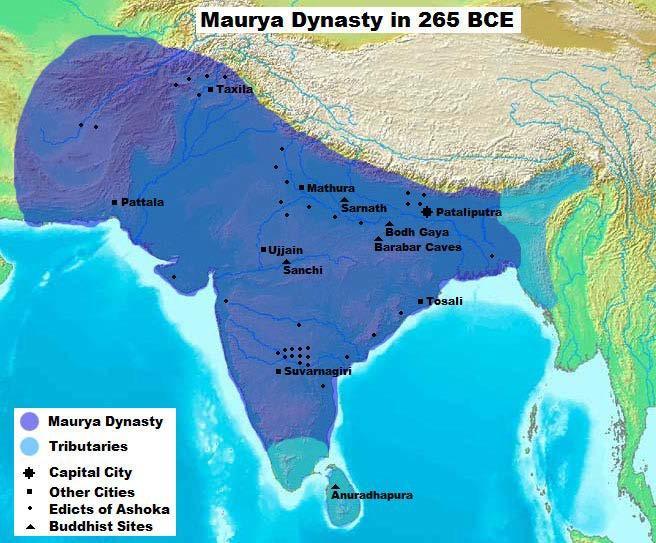

But Nanda aspirations were cut short when they were overthrown by Chandragupta Maurya (r. 321–297 BCE), who began a new period in India’s history. He and his son Bindusara (r. 287–273 BCE) and grandson Ashoka (r. 268–232 BCE) were destined to forge the first large empire in India’s history, one that would inspire the imagination of later empire builders in South Asia. The Mauryan Empire included most of the subcontinent and lasted for 140 years (see Map 3.8).

Conflicting accounts make it difficult to say anything definitive about the first two kings. Chandragupta may have come from a Kshatriya (warrior) clan or a Vaishya (commoner) clan of peacock-tamers. In his youth, he spent time in the northwest, where he encountered Alexander the Great. With the assistance of Kautilya, a disloyal Brahmin of the Nanda court, Chandragupta formed alliances with Nanda enemies, overthrowing them in 321 BCE. Thereafter, through diplomacy and war, he secured control over central and northern India.

Kautilya, whose advice may have been critical to Chandragupta’s success, is viewed as the author of the Arthashastra, a treatise on statecraft. This handbook for kings covered in detail the arts of governing, diplomacy, and warfare. To help ensure centralization of power in the ruler’s hands, it provided a blueprint of rules and regulations necessary to maintain an efficient bureaucracy, a detailed penal code, and advice on how to deploy spies and informants.

Chandragupta’s campaigns ended when he concluded a treaty with Seleucus Nicator in 301 BCE. After Alexander the Great retreated from India and then died, a struggle for his empire broke out among his generals. Seleucus was one of them. He gained control of the eastern half and sought to reclaim northwest India. But he was confronted by Chandragupta, defeated, and forced to surrender the Indus Basin and much of Afghanistan, giving the Mauryan Empire control over trade routes to West Asia. The treaty, however, established friendly relations between the two rulers, for in exchange for hundreds of elephants, Seleucus gave Chandragupta a daughter in marriage and dispatched an envoy to his court. Hellenistic kings (see Chapter 5) maintained commercial and diplomatic ties with India.

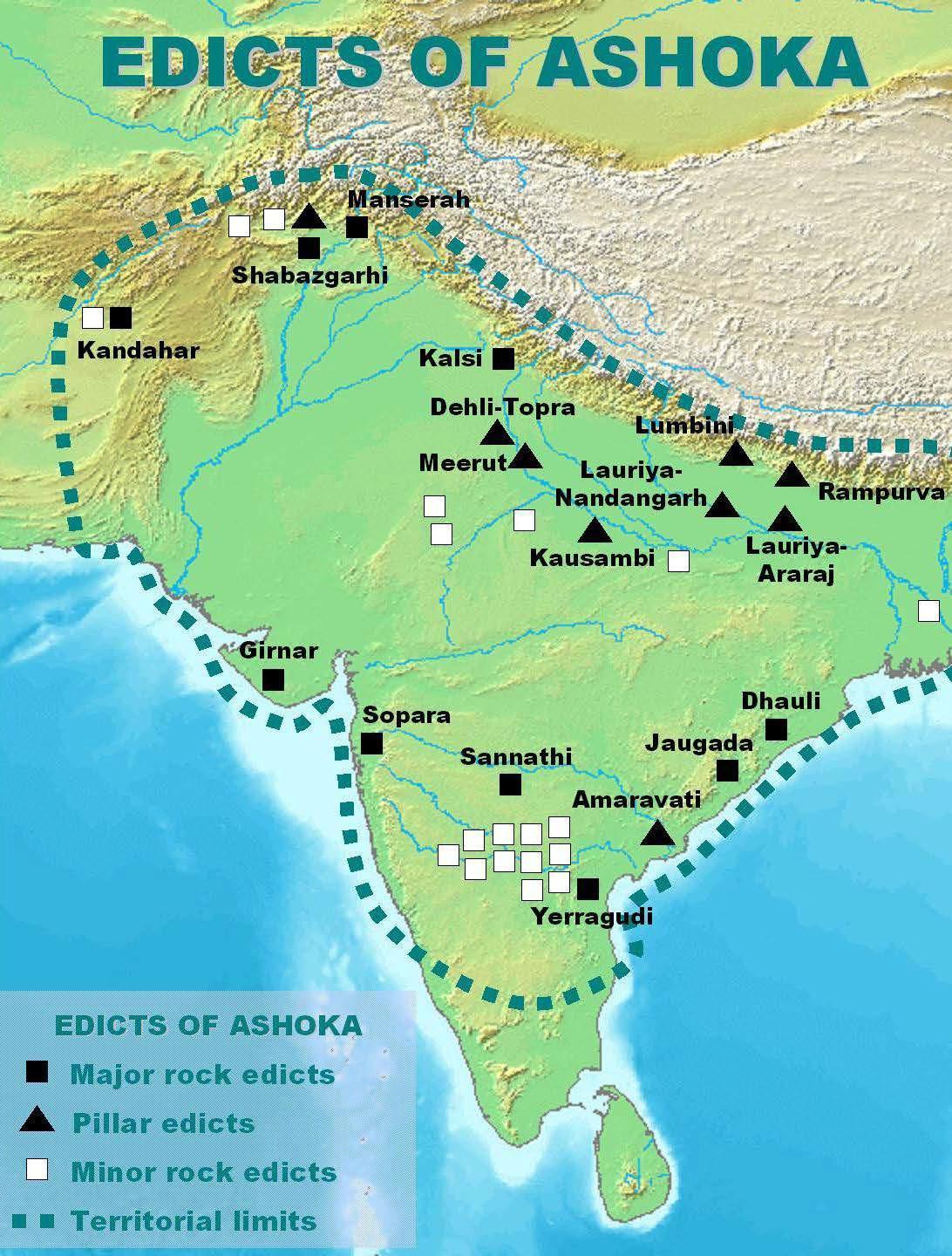

Military expansion continued under Bindusara and Ashoka until all but the tip of the subcontinent came under the empire’s control. With King Ashoka, however, warfare came to an end. We know far more about him because he left behind a fascinating record telling much about his ideas on governing. He had edicts inscribed on rocks throughout the realm and on sandstone pillars erected in the Ganges heartland (see Map 3.9). He then placed them in populous areas where people usually gathered so that his officials could read them to his largely illiterate subjects.

One rock edict speaks to why King Ashoka decided to renounce violence. While waging war against a small state located along the east coast, he was deeply disturbed by the amount of suffering and dislocation the war heaped upon innocent people’s lives. This realization caused him to redouble his faith in the Buddha. Ashoka, it turns out, was a lay follower of Buddhism.

In his edicts, he proclaimed to his subjects that the sound of the drum would be replaced by the sound of the dharma. In ancient India, dharma meant universal law. For the Brahmin priests, for example, dharma meant a society and religious order founded on Vedic principles and the caste system. For Buddhists, dharma consisted of the truths taught by the Buddha. For kings, dharma was enlightened governing and just rule. Thus, Ashoka was proclaiming that he would now rule by virtue, not force.

Ashoka’s kingly dharma was shaped by his personal practice of Buddhism. This dharma consisted of laws of ethical behavior and right conduct fashioned from Indian traditions of kingship and his understanding of Buddhist principles. To gain his subjects’ willing obedience, he sought to inspire a sense of gratitude by presenting himself in the role of a father looking out for his children. He told his subjects that he was appointing officers to tour his realm and attend to the welfare and happiness of all. Justice was to be impartially administered and medical treatment provided for animals and humans. A principle of non-injury to all beings was to be observed. Following this principle meant not only renouncing state violence but also forbidding slaughtering certain animals for sacrifices or for cooking in the royal kitchen. Ashoka also proclaimed that he would replace his pleasure and hunting tours with dharma tours. During these, he promised to give gifts to Brahmins and the aged and to visit people in the countryside.

In return, Ashoka asked his subjects to observe certain principles. He knew his empire was pluralistic, consisting of many peoples with different cultures and beliefs. He believed that if he instilled certain values in these peoples, then his realm might be knit together in peace and harmony. Thus, in addition to non-injury, Ashoka taught forbearance. He exhorted his subjects to respect parents, show courtesy to servants, and, more generally, be liberal, compassionate, and truthful in their treatment of others. These values were also to be embraced by religious communities, since Ashoka did not want people fighting over matters of faith.

The king’s writ shaped the government. They were advised by a council of ministers and served by high officials who oversaw the major functions of the state. The Mauryans were particularly concerned with efficient revenue collection and uniform administration of justice. To that end, they divided the empire into a hierarchy of provinces and districts and appointed officials to manage matters at each level. But given such an immense empire spread over a geographically and ethnically diverse territory, the level of Mauryan control varied. Historians recognize three broad zones. The first was the metropolitan region—with its capital Pataliputra—located on the Ganges Plain. This heartland was tightly governed. The second zone consisted of conquered regions of strategic and economic importance. These provinces were placed under the control of members of the royal family and senior officials, but state formation was slower. That is, the tentacles of bureaucracy did not reach as deeply into local communities. Lastly, the third zone consisted of hinterlands sparsely populated by tribes of foragers and nomads. Here, state control was minimal, amounting to little more than establishing workable relations with chieftains.

After King Ashoka’s reign, the Mauryan Empire declined. The precise reasons for this decline are unknown. Kings enjoyed only brief reigns during the final fifty years of the empire’s existence, so they may have been weak. Since loyalty to the ruler was one element of the glue that held the centralized bureaucracy together, weak kings may explain why the political leaders of provinces pulled away and the empire fragmented into smaller states. Furthermore, the Mauryan court’s demand for revenue sufficient to sustain the government and a large standing army may have contributed to discontent. In 184 BCE, the last king was assassinated by his own Brahmin military commander, and India’s first major imperial power came to an end.

3.10 REGIONAL STATES, TRADE, AND DEVOTIONAL RELIGION: INDIA 200 BCE–300 CE

After the Mauryan Empire fell, no one major power held control over a substantial part of India until the rise of the Gupta Empire in the fourth century CE. Thus, for five hundred years, from c. 200 BCE to 300 CE, India saw a fairly rapid turnover of numerous competing regional monarchies. Most of these were small, while the larger ones were only loosely integrated. Some developed along the Ganges. Others were of Central Asian origins, the product of invasions from the northwest. Also, for the first time, states formed in southern India. Yet, in spite of the political instability, India was economically dynamic, as trade within and without the subcontinent flourished, and India was increasingly linked to other parts of the world in networks of exchange. And new trends appeared in India’s major religious traditions. A popular, devotional form of worship was added to Buddhism and also became a defining element of Hinduism.

3.10.1 Regional States

The general who brought the Mauryan Empire to a close by a military coup established the Shunga Dynasty (c. 185–73 BCE). Like its predecessor, this kingdom was centered on the middle Ganges, the heartland of India’s history since the late Vedic Age. But unlike it, the Shunga Kingdom rapidly dwindled in size. Shunga rulers were constantly warring with neighboring kingdoms, and the last fell to an internal coup in 73 CE. Subsequently, during the ensuing half millennium, other regions of India played equally prominent roles.

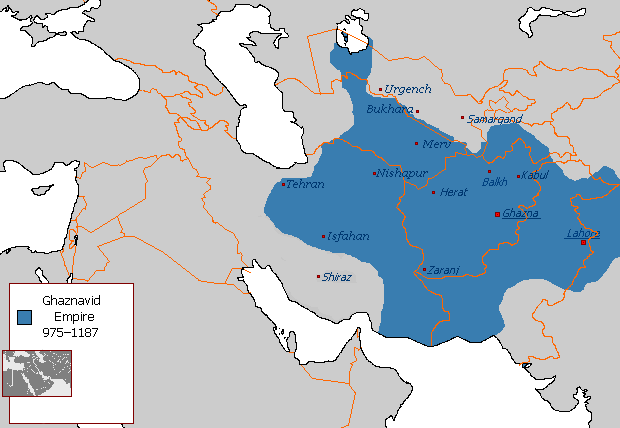

The northwest remained a source of dynamism, as different peoples living beyond the Hindu Kush invaded India and established one kingdom after another. Most of this movement was caused by instability on the steppe lands of Central Asia, where competing confederations of nomadic pastoralists fought for control over territory.

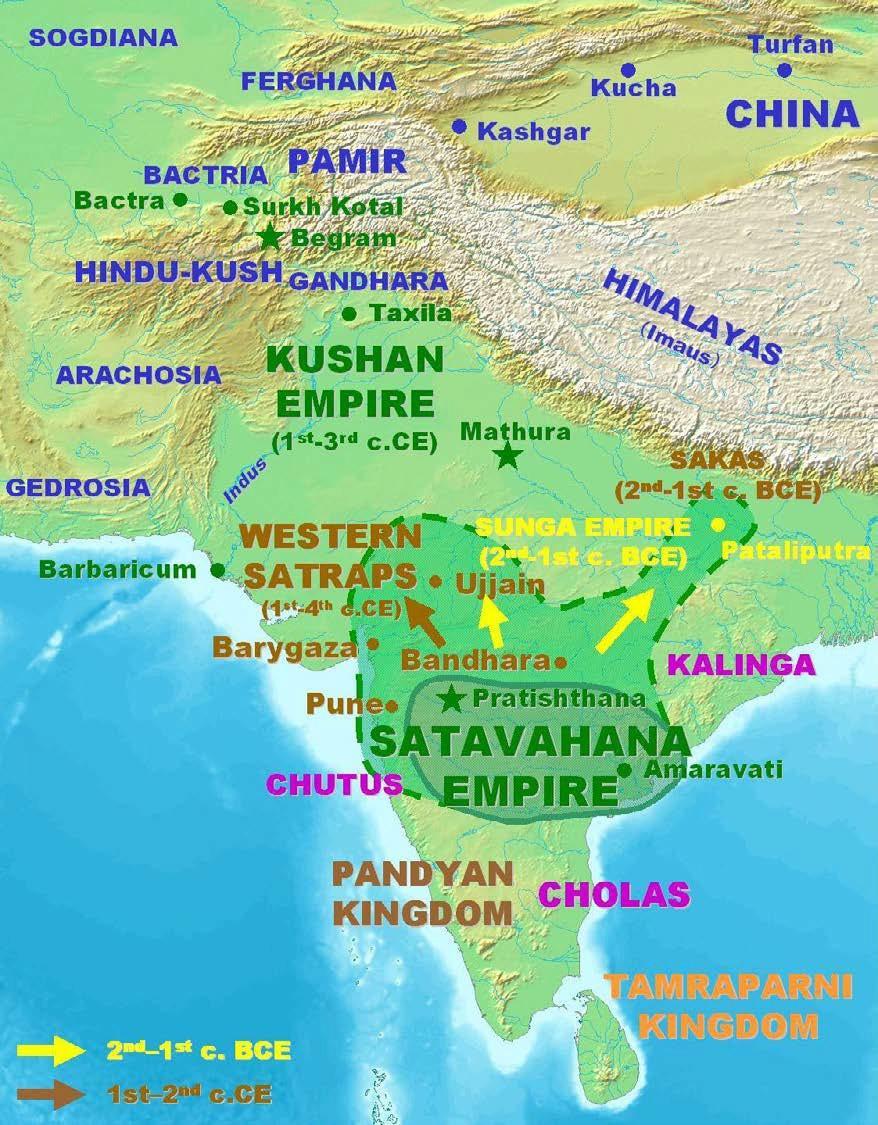

The most powerful among this succession of states was the Kushan Kingdom, whose origins take us far away to the north of China. There, in the second century CE, nomadic groups struggling with scarcity moved west, displacing another group and forcing them into northern Afghanistan. Those peoples are known as the Yuezhi (yew-eh-jer), and they were made up of several tribes. In the first century CE, a warrior chieftain from one Yuezhi tribe, the Kushans, united them, invaded northwest India, and assumed exalted titles befitting a king. His successor, ruling from Afghanistan, gained control over the Punjab and reached into the plains of the upper Ganges River.

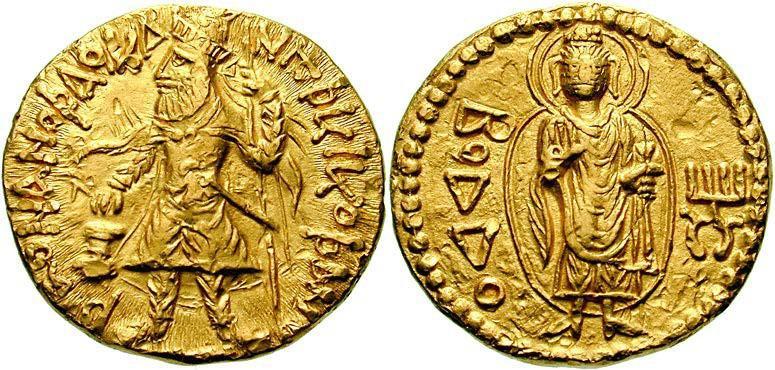

The greatest Kushan ruler, King Kanishka, furthered what these first two kings began, forging an empire extending from Central Asia across the mountain ranges of Afghanistan into much of northern India. Ruling the many peoples of such a sprawling territory required more than the periodic plundering campaigns of nomad chieftains. One sculpture of King Kanishka puts these Central Asian roots on display (see Figure 3.7). In it, he is wearing a belted tunic, a coat, and felt boots and carrying a sword and mace. Kushan gold coins, however, cast him and his two predecessors in another light: as universal monarchs (see Figure 3.8). On one side, the crowned kings are displayed along with inscriptions bearing titles used by the most powerful Indian, Persian, Chinese, and Roman emperors of that time. The obverse side contains images of both Indian and foreign deities. The Kushan rulers, it appears, solved the problem of ruling an extensive, culturally diverse realm by patronizing the many different gods beloved by the peoples living within it. Buddhists, for instance, saw King Kanishka as a great Buddhist ruler, much like they did King Ashoka. In fact, Kanishka supported Buddhist scholarship and encouraged missionaries to take this faith from India to Central Asia and China. But his coins also depict Greek, Persian, and Hindu deities, suggesting that he was open-minded, and perhaps strategic, in matters of religion.

After Kanishka’s reign, from the mid-second century CE onwards, the empire declined. Like the other larger Indian states during this time, only a core area was ruled directly by the king’s servants. The other areas were governed indirectly by establishing tributary relations with local rulers. As Kushan power waned, numerous smaller polities emerged, turning northern and central India into a mosaic of states.

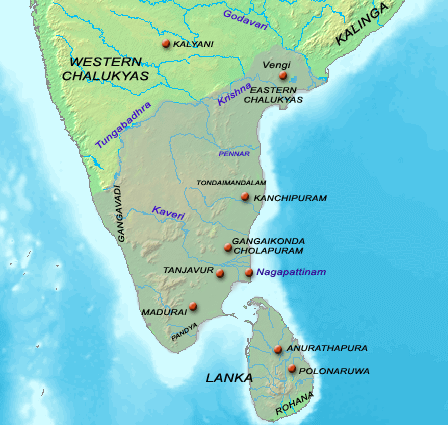

The Indian peninsula—the territory south of the Indo-Gangetic Plain and the Vindhya Mountain Range—also features more prominently after the fall of the Mauryan Empire. In the south, kingdoms emerged for the first time. The largest was the Satavahana Kingdom, which included most of the Deccan Plateau and lasted about three centuries. The first rulers were former Mauryan officials who capitalized on its dissolution, established their own state, and expanded to the north (see Map 3.10). To establish their legitimacy, Satavahana kings embraced Aryan civilization by allowing Brahmins to perform sacrifices at the court and by upholding the varna social order. They also prospered from a rich agricultural base and trade. However, like so many of the larger states during these centuries, this kingdom was only loosely integrated, consisting of small provinces governed by civil and military officers and allied, subordinate chieftains and kings.

3.10.2 Economic Growth and Flourishing Trade Networks

Gold coins discovered in Kushan territory provide much information about the rulers who issued them. The Satavahanas also minted coins. Additionally, Roman gold coins have been found at over 130 sites in south India. These were issued by Roman emperors at the turn of the Christian era, during the first century CE. These coins serve as a sign of the times. Indian monarchs issued coins because trade was growing and intensifying all around them, and they wished to support and profit from it. Expanding the money supply facilitated trade and was one way to achieve that goal. Both Indian kingdoms were also geographically well positioned to take advantage of emerging global trade networks linking the subcontinent to other regions of Afro-Eurasia. This advantage provides one reason why they flourished.

The expansion of trade both within and without India is a major theme of these five centuries. Put simply, South Asia was a crossroads with much to offer. In market towns and cities across the subcontinent, artisans and merchants organized to produce and distribute a wide variety of goods. Guilds were their principal method of organization. A guild was a professional association made up of members with a particular trade. Artisan guilds—such as weavers and goldsmiths—set the prices and ensured the quality of goods. Operating like and sometimes overlapping with castes, guilds also set rules for members and policed their behavior. They acted collectively as proud participants of urban communities, displaying their banners in festive processions and donating money to religious institutions. Merchant guilds then saw to it that their artisan products were transported along routes traversing the subcontinent or leading beyond to foreign lands.

The lands and peoples surrounding India, and the many empires they lived under, are the topic of later chapters, but we can take a snapshot of the scene here (see Map 3.11). In the first century CE, India sat amidst trade networks connecting the Roman Empire, Persian Empire (Parthian), Chinese Empire, and a host of smaller kingdoms and states in Africa, Central Asia, and Southeast Asia. The major trade networks were the Silk Roads and the Indian Ocean maritime trade routes. Thus, for example, Greco-Roman traders plied the waters of the Arabian Sea, bringing ships filled with amphorae and gold coins to ports located along the west coast of India and returning with spices, textiles, and gems. Indian traders sailed the waters of the Bay of Bengal, bringing cloth and beads from the Coromandel Coast to Southeast Asia and returning with cinnamon cloves and sandalwood. In the northwest, a similar trade in a variety of goods took place along the Silk Roads. Indian traders, for instance, took advantage of the excellent position of the Kushan Empire to bring silk from Central Asia to the ports of northwest India, from where it could then be sent on to Rome. In sum, this vibrant international trade constituted an early stage of globalization. Combined with regional trade across the subcontinent, India saw an increase in travel in all directions, even as it remained divided among many regional kingdoms.

3.10.3 Religious Transformations: Buddhism and Hinduism into the Common Era

Aside from expanding trade, another theme during these centuries of political division is transformations in two of India’s major religious traditions: Buddhism and Hinduism. In both cases, new religious ideas and practices were added that emphasized the importance of devotion and appealed to broader groups of people.

Buddhism thrived after the Buddha died in c. 480 BCE, all the more so during this period of regional states and the early centuries of the Common Era, at the very moment Christianity was spreading through the Roman Empire. In fact, it would not be an exaggeration to say that Buddhism was the dominant public religion. The communities of monks and nuns (sangha) that formed after Buddha’s time lived in monasteries built along trade routes, near towns, or in caves. To build these and survive, the sangha needed much support, which often came in the form of royal patronage. Kings such as Ashoka and Kanishka, for example, offered lavish support for Buddhist institutions. But over time, the contributions of merchants, women, and people from lower varnas became just as important. Unlike Vedic Brahmanism, which privileges the Brahmin varna, Buddhism was more inclusive and less concerned with birth and social class. After all, in theory, anyone could become a Buddha.

Buddhism also emphasized the importance of attaining good karma for better rebirths and a future enlightenment; one didn’t need to be a monk to work at this. Rather, any ordinary layperson, regardless of their religious beliefs, could also take Buddhist vows and practice Buddhist ways. That meant not only leading a moral life but also supporting the sangha. By doing so, the good karma of the monks and nuns would be transferred to the community and oneself. This practice served not only to make the world a better place and to ensure a better future but also to allow opportunities for publicly displaying one’s piety. That is why kings, rich merchants, and ordinary people donated to the sangha and gave monks food.

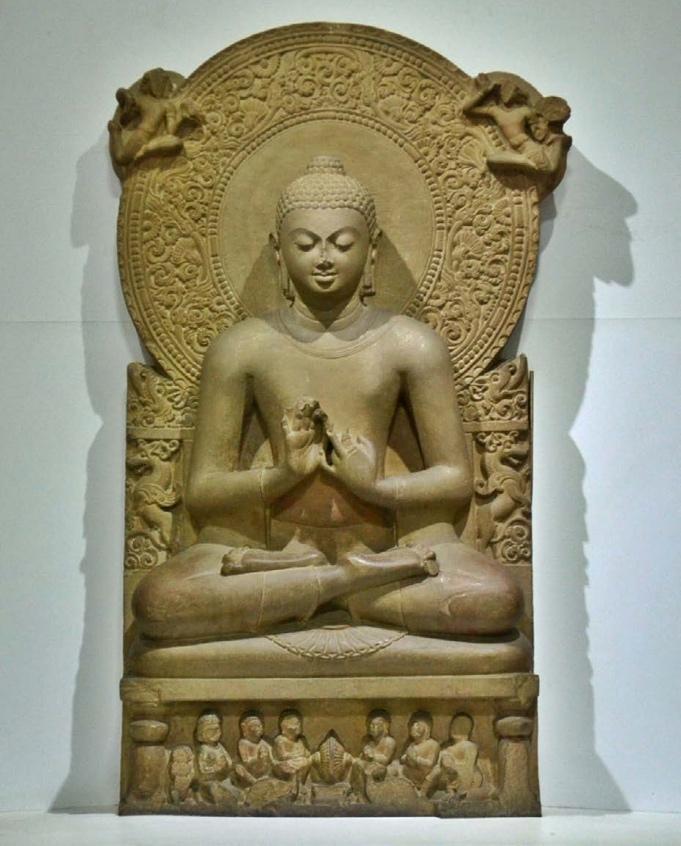

With so much support and participation, Buddhism also changed. Every major world religion has different branches. Christianity, for example, has three major ones: the Roman Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, and Protestant churches. These branches share a common root but diverge in some matters of belief and practice. Buddhism has two major branches: Theravada and Mahayana Buddhism. Theravada Buddhism is early Buddhism, the Buddhism of the early sangha, and is based on the earliest records of the Buddha’s teaching of the Four Noble Truths. A practitioner of this form of Buddhism sought to end suffering and attain nirvana by engaging the Eightfold Path, a program of study, moral conduct, and meditation. Ideally, the practitioner pursued this program as a monk or nun in a monastic setting and eventually became an “arhat”—that is, a perfected person who is nearly or fully enlightened.

Mahayana Buddhism came later, during the early centuries of the Common Era. Mahayana means “Great Vehicle,” pointing to the fact that this form of Buddhism offers multiple paths to enlightenment for people from all walks of life. This branch has no single founder and consists of a set of ideas elaborated upon in new Buddhist scriptures dating to this time. In one of these new paths, the Buddha becomes a god who can be worshipped, and by anyone. A monk or lay follower is welcome to make an offering before an image of the Buddha placed in a shrine. By doing so, they demonstrate their desire to end suffering and seek salvation through faith in the Buddha.

Furthermore, with the “Great Vehicle,” the universe becomes populated with numerous Buddhas. Practitioners developed the idea that if anyone can become a Buddha over the course of many lifetimes of practice, then other Buddhas must exist. Also, the belief arose that some individuals had tread the path to Buddhahood but chose to forego a final enlightenment where they would leave the world behind so that they could, out of great compassion for all suffering people, work for their deliverance. These holy beings are known as Bodhisattvas—that is, enlightened persons who seek nirvana solely out of their desire to benefit all humanity. Buddhists also believed that the universe consisted of multiple worlds with multiple heavenly realms. Some of these Buddhas and Bodhisattvas created their own heavenly realms and, from there, offer grace to those seeking salvation through them. Through veneration and worship, the follower hopes to be reborn in that heavenly realm, where they can then finish the path to liberation. Seeking to become a Bodhisattva through a path of devotion was one of the new paths outlined by Mahayana scriptures.

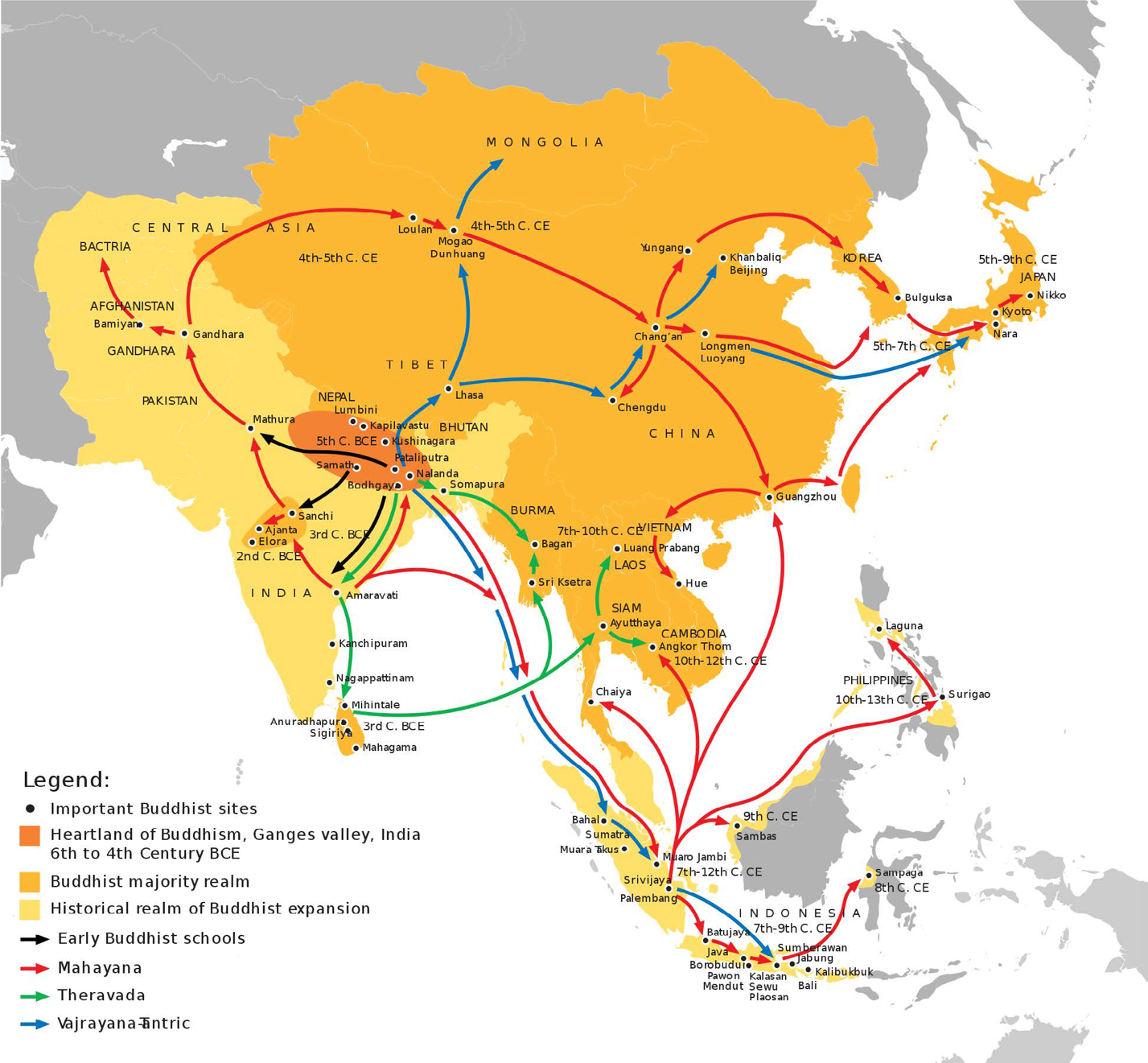

Buddhism traveled out of India and had an impact on other parts of the world, making it a major world religion. This expansion resulted from the efforts of Buddhist missionaries and merchants, as well as kings who supported its propagation. Theravada Buddhism was carried to Sri Lanka and parts of Southeast Asia, where it remains a dominant religious tradition. Mahayana Buddhism spread to Central and East Asia, a process that was facilitated by the Silk Road and the support of kings like Kanishka of the Kushan Empire (see Map 3.12). However, Buddhism eventually declined in India, especially after the first millennium BCE. From that time, Hinduism and Islam increasingly won over the religious imagination of the peoples of India, with royal patronage and lay support following.

Hinduism also saw new developments during this period and throughout the first millennium CE. In fact, many scholars see these centuries as the time during which Hinduism first took shape and prefer using the term Vedic Brahmanism for the prior history of this religious tradition. Vedic Brahmanism was the sacrifice-centered religion of the Vedas where, in exchange for gifts, Brahmins performed rituals for kings and householders in order to ensure the favor of the gods. It also included the speculative world of the Upanishads, where renunciants went out in search of spiritual liberation.

But something important happened during these later centuries. Additional religious literature was compiled, and shrines and temples with images of deities were constructed, pointing to the emergence of new, popular forms of devotion and an effort to define a good life and society according to the idea of dharma. With this transition, we can speak more formally of Hinduism. One important set of texts is the Dharma Scriptures, ethical and legal works whose authority derived from their attribution to ancient sages. Dharma means “duty” or proper human conduct, and so, true to their title, these scriptures define the rules each person must follow in order to lead a righteous and devout life and contribute to a good society. Most importantly, these rules were determined by the role assigned to an individual by the varna system of social classes, the caste system, and gender. For example, for a male, dharma meant following the rules for their caste and varna while passing through four stages in life: student, householder, hermit, and renunciant. In his youth, a man must study to prepare for his occupation, and as a householder, he must support his family and contribute to society. Later in life, after achieving these goals, he should renounce material desires and withdraw from society, living first as a hermit on the margins of society and then as a wandering renunciant whose sole devotion is to god.

A woman’s roles, on the other hand, were defined as obedience to her father in youth and faithful service to her husband as an adult. For this reason, historians see a trend in ancient Indian history whereby women became increasingly subservient and subordinate. Although women were to be honored and supported, the ideal society and family were defined in patriarchal terms. That meant men dominated public life, were the authority figures at home, and usually inherited the property. Also, women were increasingly expected to marry at a very young age—even prior to puberty—and to remain celibate as widows. In later centuries, some widows even observed the practice of burning themselves upon the funeral pyre of their deceased husband. Famous Indian epics also illustrated the theme of duty. The Ramayana (“Rama’s Journey”) tells the story of Prince Rama and his wife Sita. Rama’s parents—the king and queen—wished for him to take the throne, but a second queen plotted against him and forced him into exile for years. Sita accompanied him but was abducted by a demon-king, leading to a battle in consequence. With the help of a loyal monkey god, Rama defeated the demon, recovered his wife, and returned with her to his father’s kingdom, where they were crowned king and queen. In brief, throughout this long story, Rama exemplified the virtues of a king, and Sita exemplified the virtues of a daughter and wife. They both followed their dharma.