Chapter 8: Islam to the Mamluks

Brian Parkinson

8.1 CHRONOLOGY

|

Chronology |

Islam to the Mamluks |

|

~2nd c. BC–6th c. CE |

Himyar Kingdom |

|

570–632 CE |

Life of Muhammad |

|

632–661 CE |

Rashidun Caliphate |

|

661–750 CE |

Umayyad Caliphate |

|

750–1258 CE |

Abbasid Caliphate |

|

909–171 CE |

Fatimid Caliphate |

|

1096–1487 CE |

Crusades |

|

1171–1250 CE |

Ayubid Sultanate |

|

1250–1517 CE |

Mamluk Sultanate |

8.2 INTRODUCTION

In the fourteenth century, Ibn Khaldun was born in present-day Tunisia. He received a traditional Islamic education until his parents died from the plague. At the time of their deaths, he was just seventeen years old. On his own, the young and resourceful Ibn Khaldun exploited personal relationships to secure an administrative position at court and thus began his lifetime career. Time and time again, Ibn Khaldun landed in prison for his role in conspiracies against various ruling dynasties, only to be released later. Envoys and grandees recognized his remarkable intelligence and the value of his council. His reputation preceded him, and many dignitaries openly asked him to join their court. Serving various dynasties, Ibn Khaldun held many important offices, like diplomat, court advisor, and prime minister. But he eventually grew weary of the hazards of palace intrigue and sought instead a more reclusive lifestyle.

Ibn Khaldun retired to the safety of a Berber tribe in Algeria, where he composed Prolegomenon, an outstanding work of sociology and historiography. Published in 1377, he theorized that tribal ‘asabiyah, roughly translated as “social solidarity,” is often accompanied by a novel religious ideology that helps a previously marginalized group of people, usually from the desert, rise up and conquer the city folk. Once ensconced in power, these desert peoples evolved into a grand civilization, but ‘asabiyah contained within it destructive elements that could precipitate their collapse. Known for this Cyclical Theory of History, Ibn Khaldun argued that, seduced by the attractions of urban culture, the dominant group would over time become soft and enter into a period of decay, until a new group of desert peoples conquered them, when the process would begin anew. This theory applies to the development of Islamic history discussed throughout this chapter.

8.3 QUESTIONS TO GUIDE YOUR READING

- How does geography play a role in Islamic history?

- Why were the concepts defined by muruwah so important to the early development of Islam?

- What are the Five Pillars of Islam, and why are they important to the religion?

- What were the five roles that the Prophet Muhammad played in Medina?

- What factors led to the rapid expansion of Islam?

- How did the Umayyads come to power following the Rashidun caliphs?

- Describe the transition from the Umayyads to the Abbasids. Compare and contrast the two caliphates.

- The Fatimids marked the end to the High Caliphate. How did Egypt gain its autonomy from the Abbasids? How did the Fatimids take over Egypt?

- How did the Crusaders gain a foothold in the Middle East? What did it take for Salah al-Din to push them out?

- What led to the establishment of the Mamluk Sultanate? How did the Mamluk Sultanate go into decline?

- Does North African history move in cycles of birth, renewal, expansion, and decadence? Ibn Khaldoun says that nomads come from the frontiers, desert, and periphery, settle down, and within 120 years, become decadent and collapse. Do you agree?

8.4 KEY TERMS

- Abu Bakr, caliph

- ‘A’isha

- ‘Ali, caliph

- Al-Mu‘izz

- Alexios Komnenos, emperor

- Alids

- Asabiyyah

- Aybak

- Battle of Badr

- Battle of Karbala

- Battle of the Trench

- Battle of Uhud

- General Baybars

- Cyclical Theory of History

- Hadith

- Hajj

- Harun al-Rashid, caliph

- Hijra

- Husayn

- Ibn Khaldun

- Isma‘ilis

- Jihad

- Jizya

- Ka‘ba

- Khilafa (caliphate)

- Mamluks

- Mawali

- Mecca

- Medina

- Muruwah

- People of the Book

- Quran

- Qutuz

- Ramadan

- Salah al-Din

- Salat

- Sawm

- Shahada

- Sharia law

- Sunna

- ‘Umar, caliph

- ‘Umar II, caliph

- Umma(h)

- Urban II, pope

- ‘Uthman, caliph

- Yazid

- Yathrib (Medina)

- Zakat

8.5 GEOGRAPHY OF THE MIDDLE EAST

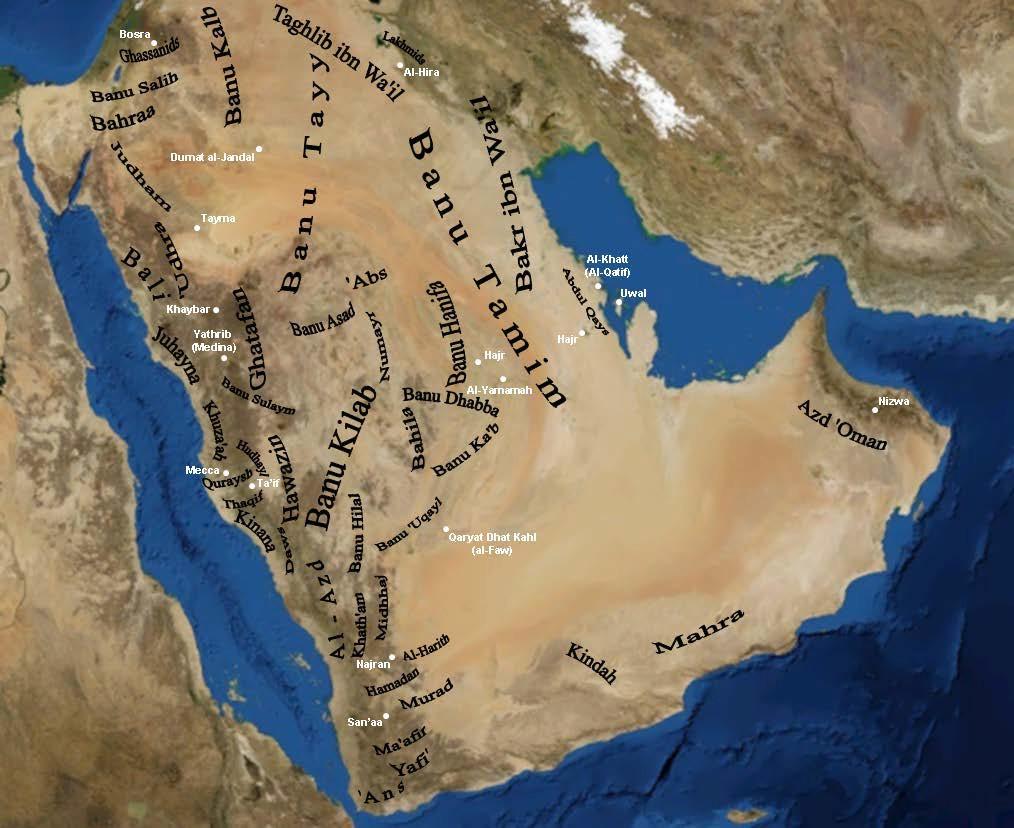

Academics have not reached a consensus on the geographical boundaries of the Middle East. However, for the purposes of this chapter, this region will encompass the broadly defined areas known as Persia, Mesopotamia, the Levant, Asia Minor, and the Arabian Peninsula. The Middle East straddles three continents, including Asia, Africa, and Europe. The geography of the area promoted cultural diffusion by facilitating the spread of peoples, ideas, and goods along overland and maritime trade routes. In an area generally characterized by its aridity, climate has influenced settlement patterns. Larger settlements were found in river valleys and well-watered areas along the littoral. In these areas, we see the development and spread of productive agriculture.

8.6 ARABIA BEFORE ISLAM

Legend traces the Arabs back to Isma‘il, the son of Abraham and his Egyptian maid, Haga, a link that would later help to legitimize Islam by connecting it to the Hebrew tradition. In reality, Arabs inhabited the pre-Islamic Arabian Peninsula and shared socio-linguistic commonalities with such other Semitic-speaking peoples in the area as the Hebrews, Assyrians, Arameans, and even the Amhara of Ethiopia. For much of ancient history, Arabia was an unorganized land between the great empires of Mesopotamia and the Egyptian kingdom of the pharaohs. From the beginning of the first millennium BCE, Southern Arabia was home to a number of kingdoms, such as the Sabaean kingdom, while Eastern Arabian lands were controlled by the Iranian Parthians and Sassanians from 300 BCE.

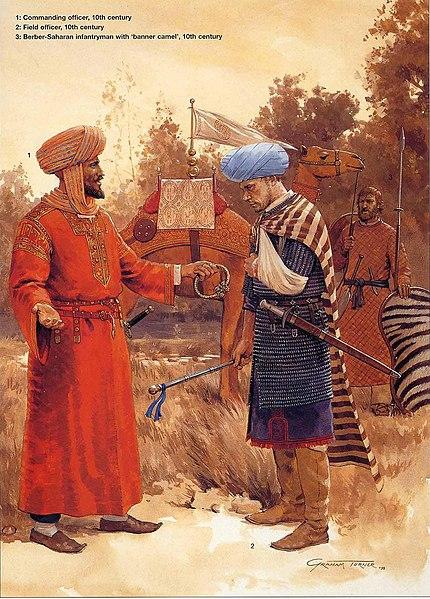

The nomadic pastoralist Bedouin tribes inhabited the Arabian Peninsula before the rise of Islam. The population was thinly spread out across the entire peninsula. Society was patriarchal, and life was centered around the tribe, a group of relatives who claimed a shared ancestry. Tribes provided a means of protection for their members; death to one clan member meant brutal retaliation. Because of the harsh climate and the seasonal migrations required to obtain resources, the Bedouin tribes generally raised sheep, goats, and camels. Each member of the family had a specific role in taking care of the animals, from guarding the herd to making cheese from milk. The Bedouin also hunted, served as bodyguards, escorted caravans, and worked as mercenaries. Some tribes traded with towns in order to gain goods, while others raided other tribes for animals, women, gold, fabric, and other luxury items. In pre-Islamic Arabia, women’s status varied widely according to the laws and cultural norms of the tribes in which they lived, but one thing they had in common was the lack of any legal status. Women were often considered property to be inherited or seized in a tribal conflict. Not unique to Arabia, there were also instances of abuse of women and girls, including instances of killing female infants if they were considered a liability.

Like later cultures in the region, the Bedouin tribes placed heavy importance on poetry and oral tradition as a means of communication. Poetry was used to communicate within the community and sometimes promoted tribal propaganda. Tribes constructed verses against their enemies, often discrediting their people or fighting abilities. Poets maintained sacred places in their communities because they were thought to be divinely inspirited. Poets often wrote in classical Arabic, which differed from the common tribal dialect. Poetry was also a form of entertainment, as many poets constructed prose about the nature and beauty surrounding their nomadic lives.

Tribal traditions found meaning in the poetic concept of muruwah, which represented the notion of the ideal tribal man. This uniquely Arabian brand of chivalry focused on bravery, patience, persistence in revenge, generosity, hospitality, and protection of the poor and weak. In the absence of formal government, tribes offered physical security to their individual members. Tribes mitigated violence and theft through the shared understanding that retribution for such acts would follow swiftly. Tribes also organized to compete over increasingly scarce resources, as they had a responsibility to provide for the economic needs of their individual members. Nevertheless, tribal traditions had been breaking down prior to the rise of Islam; no longer were the dominant members of society adhering to the principles set forth in muruwah.

Pre-Islamic religion in Arabia consisted of indigenous polytheistic beliefs, Ancient Arabian Christianity, Nestorian Christianity, Judaism, and Zoroastrianism. Christianity existed in the Arabian Peninsula and was established first by the early Arab traders who were familiar with Christianity. Many people in Arabia identified as “hanif,” meaning they followed a monotheistic version of the Abrahamic religion, not considered Jewish or Christian, but more loosely organized.

Most of the population resided in the south of the peninsula, in modern-day Yemen, where they practiced terraced agriculture and herded animals in a relatively small area. Farther to the north of Yemen, along the highland spine of western Arabia and up against the littoral of the Red Sea, was the Hijaz, a prominent cultural and economic region. Situated in this remote fastness was the dusty city of Mecca, the holiest place in the peninsula. Mecca was also home to the Ka‘ba, or cube, which contained many of the traditional Arabian religious images, including many Christian icons. So important was the Ka‘ba to the religion of polytheistic tribes of Arabia that they negotiated a truce lasting one month every year that allowed for safe pilgrimage to the shrine.

The Hijaz was the most arable part of the Arabian Peninsula and distinguished by irrigated agriculture that supported fruit trees and essential grains. Local traders exported a range of agricultural products to Syria in the north in return for imports like textiles and olive oil. Regional commerce depended on the security of trade, while piracy on the Red Sea threatened to disrupt business. Under these conditions, merchants diverted their trade overland. Caravans of camels carried these goods, as well as Hijazi exports, to the Levant or the eastern Mediterranean area. Most of the caravans stopped in Mecca, the halfway point up the spine of the peninsula, thus their commerce brought much-needed wealth and tax revenue to the city.

The Arabs first domesticated the dromedary camel probably sometime between 3000 and 1000 BCE. Caravan operators eventually availed themselves of these useful dromedaries because they were so adept at crossing the region’s massive deserts. Capable of drinking 100 liters of water in mere minutes, they could endure days of travel without needing to replenish themselves again. Moreover, camels instinctively remembered the locations of important, life-sustaining oases. So important were these beasts of burden that the tribes that controlled the camels controlled the trade. And the Quraysh Tribe of Mecca commanded many of the camels in the Hijaz region; therefore, they commanded much of the trade.

8.7 RISE OF ISLAM

Into this heterogeneous and evolving cultural milieu Muhammad (c. 570–632) was born in the city of Mecca. Muhammad was orphaned at just six years of age, but his tribe intervened to ensure Muhammad’s survival. His uncle, Abu Thalib, an important member of the Quraysh Tribe, eventually took custody of the young boy. These early experiences influenced Muhammad’s later desire to take care of those who could not care for themselves.

In his youth, Muhammad found employment in the regional caravan trade as a dependable herder and driver of camels. During this period, he cultivated a reputation of an empathetic and honest man, one who earned the respect of many Meccans. His upright character soon attracted the attention of a wealthy merchant known as Khadija, who hired Muhammad to manage her caravans. Once Muhammad proved his reliability, Khadija, who was fifteen years older than Muhammad, proposed to him, and they married. This marriage afforded Muhammad a financial security that allowed him to begin meditating on religion.

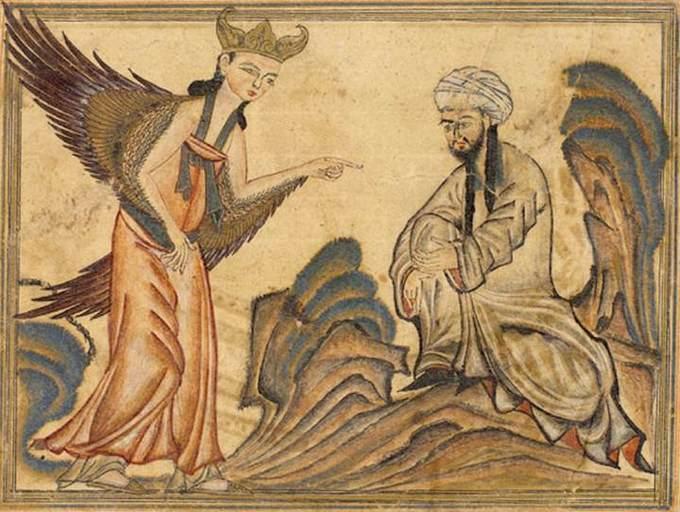

Muhammad had been concerned about the direction of society and the decline of muruwah, or traditions of manhood. He believed that some of the most influential members of society, namely the merchant elite of the Quraysh Tribe, were no longer respecting their traditional responsibilities to guide the weaker members of society because of their own greed. Muhammad had contact with many different cultures, including People of the Book, specifically Christians and Jews. He even traveled to Christian Syria while working in the caravan trade. In this context, the Angel Gabriel appeared to Muhammad at a cave near Mecca in 610, during the holy month of Ramadan. The Angel Gabriel instructed him to “recite,” and then he spoke the divine word of God. His revelations became the Quran, the sacred text of Islam.

At first, Muhammad displayed the very human reactions of fear and distrust to the apparition of the Angel Gabriel. He also expressed embarrassment because he did not want to be associated with the pagan diviners of the region. Fortunately, his wife Khadija had a cousin who was a hanif but who believed in a vague concept of a monotheistic god. Her cousin trusted the veracity of Muhammad’s revelations. So with trepidation, Muhammad eventually accepted his role as God’s vehicle. His wife became the first convert to Islam, with Abu Thalib’s son ‘Ali converting soon afterwards.

The key themes of the Quran included the responsibility of man towards his creator; the resurrection of the dead, God’s final judgment followed by vivid descriptions of the tortures in Hell and pleasures in Paradise; and the signs of God in all aspects of life. Religious duties required of the believers at this time were few: believing in God, asking for forgiveness of sins, offering frequent prayers, and assisting others, particularly those in need. According to the Quran, one of the main roles of Muhammad was to warn the unbelievers of their punishment at the end of the world. The Quran does not explicitly refer to Judgment Day but provides examples from the history of extinct communities and warns Muhammad’s contemporaries of similar calamities. Muhammad not only warned those who rejected God’s revelation but also dispensed good news for those who abandoned evil, listened to the divine words, and served God. Islam’s mission also involves preaching monotheism; the Quran commands Muhammad to proclaim and praise the name of his Lord and instructs him not to worship idols or associate other deities with God.

8.7.1 The Religion of Islam

As a religion of the Abrahamic faith, Islam holds much in common with Judaism and Christianity. Islam grew out of the Judeo-Christian tradition, a link which helped to legitimize the new religion. In fact, Muslims believe in the same God, or Allah in Arabic, as the Jewish Yahweh or the Christian God. Although Muslims trust that the People of the Book had received the word of God, they believe that it had become distorted over time, so God sent the Angel Gabriel to deliver His word to Muhammad, and Muslims believe that he represented God’s final word to man. Muhammad never claimed to found a new religion; rather, he served as the last in a long line of God’s messengers, beginning with the Hebrew prophets and including Jesus. His revelations, therefore, represent the pure, unadulterated version of God’s message. The Prophet’s followers memorized the revelations and ultimately recorded them in a book called the Quran.

Together with the Quran, two additional sources helped guide Muslims on proper behavior: the Hadiths, or the traditions of Muhammad, and the Sunna, the teachings of the Prophet not found in the Quran. All of these sacred texts provide examples and resources for Muslims, followers of Islam, to help them make decisions. And with that knowledge comes great responsibility, as God holds His people to a high standard of behavior based on their obedience, or submission, to His will. In fact, the word Islam means “submission” in Arabic, and a Muslim is one who submits (to God).

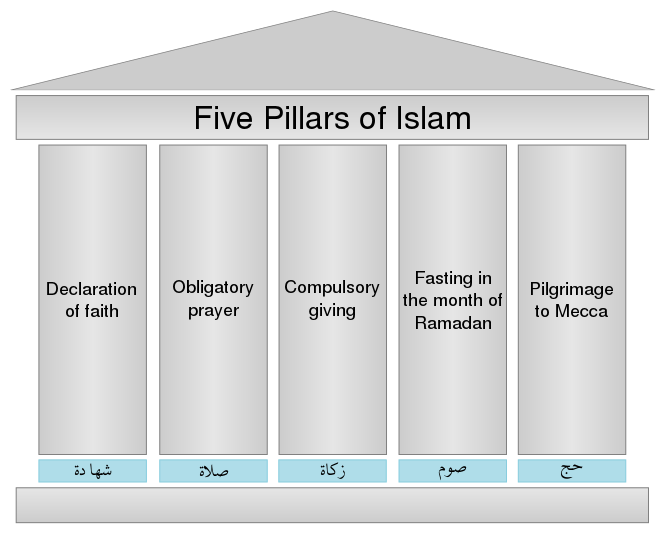

Derived from a Hadith, the Five Pillars of Islam are essential, obligatory actions that serve as the foundation of the faith.

1) The first pillar is a profession of faith, known as shahada, in which believers declare that “There is no God but God, and Muhammad is His messenger.”

2) Prayer, also called salat, is the second pillar of Islam. Islam expects faithful Muslims to pray five times a day, kneeling towards Mecca, at dawn, noon, afternoon, sunset, and evening. One should perform ritual ablutions prior to their prayers in order to approach God as being symbolically clean and pure.

3) The third pillar is almsgiving, or zakat in Arabic. Islam requires Muslims to contribute a proportion of their wealth to the upkeep of the Islamic community. This proportion, or tithe, accords with the size of one’s wealth; therefore, the rich should expect to contribute more than the poor.

4) Fasting, or sawm, is the fourth pillar of Islam and takes place during Ramadan, the ninth month of the Islamic lunar calendar. For the duration of Ramadan, believers consume neither food nor drink from dawn to dusk and generally eat minimally at other times. This practice is meant to remind them of what it is like to be poor and go hungry.

5) The fifth and final pillar of Islam is pilgrimage, or hajj. Islam expects all able-bodied Muslims to make a journey to Mecca at least once in their lifetime. All five pillars combine to unite the Islamic community.

8.8 THE GROWTH OF ISLAM

The Prophet Muhammad started publicly preaching his strict brand of monotheism in the year 613 by reciting the Quran, quickly obtaining followers. Most of his early converts belonged to groups of people who had failed to achieve any significant social mobility, which, of course, included many of the poor. His followers memorized his recitations and message that called for the powerful to take care of the weak, a message that resonated with many of these economically and socially marginalized people. Islam served as a binding force, replacing tribal solidarity, or ‘asabiyah.

8.8.1 Muhammad’s Relations with the Tribes of Mecca

According to Ibn Sad, one of Muhammad’s companions, the opposition in Mecca started when Muhammad delivered verses that condemned idol worship and polytheism. However, the Quran maintains that it began when Muhammad started public preaching. The ruling tribes of Mecca perceived Muhammad as a danger that might cause tensions similar to the rivalry of Judaism and Bedouin Polytheism in Yathrib. The powerful merchants in Mecca attempted to convince Muhammad to abandon his preaching by offering him admission into the inner circle of merchants and an advantageous marriage. However, Muhammad turned down both offers.

Muhammad’s message of monotheism challenged the traditional social order in Mecca. The Quraysh Tribe controlled the Kaaba and drew their religious and political power from its polytheistic shrines, so they began to persecute the Muslims, and many of Muhammad’s followers became martyrs. At first, the opposition was confined to ridicule and sarcasm but later morphed into active persecution that forced a section of new converts to migrate to neighboring Abyssinia (present-day Ethiopia). Upset by the rate at which Muhammad was gaining new followers, the Quraysh proposed adopting a common form of worship, which was denounced by the Quran.

Muhammad himself was protected from physical harm as long as he belonged to the Banu Hashim clan, but his followers were not so lucky. Sumayyah bint Khabbab, a slave of the prominent Meccan leader Abu Jahl, is famous as the first martyr of Islam; her master killed her with a spear when she refused to give up her faith. Bilal, another Muslim slave, was tortured as more and more rocks were placed on his chest to force his conversion, until he died.

Muhammad’s wife Khadijah and uncle Abu Talib both died in 619 CE, the year that became known as the “year of sorrow.” With the death of Abu Talib, Abu Lahab assumed leadership of the Banu Hashim clan. Soon after, Abu Lahab withdrew the clan’s protection from Muhammad, endangering him and his followers. Muhammad took this opportunity to look for a new home for himself and his followers. After several unsuccessful negotiations, he found hope with some men from Yathrib (later called Medina). They hoped, by the means of Muhammad and the new faith, to gain supremacy over Mecca. A delegation from Medina, consisting of the representatives of the twelve important clans of Medina, invited Muhammad as a neutral outsider to serve as the chief arbitrator for the entire community. The delegation from Medina pledged themselves and their fellow citizens to accept Muhammad into their community and to physically protect him as one of their own.

8.8.2 The Hijra

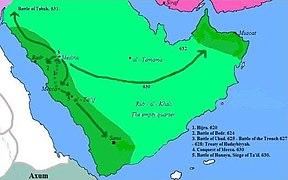

The Hijra is the migration of Muhammad and his followers from Mecca to Medina, 320 kilometers (200 miles) north, in 622 CE. Muhammad instructed his followers to emigrate to Medina until nearly all of them left Mecca. According to tradition, the Meccans, alarmed at the departure, plotted to assassinate Muhammad. In June 622, when he was warned of the plot, Muhammad slipped out of Mecca with his companion, Abu Bakr.

On the night of his departure, Muhammad’s house was besieged by the appointed men of Quraysh. It is said that when Muhammad emerged from his house, he recited a verse from the Quran and threw a handful of dust in the direction of the besiegers, which prevented them from seeing him. When the Quraysh learned of Muhammad’s escape, they announced a large reward for bringing him back to them, alive or dead, and pursuers scattered in all directions. After an eight-day journey, Muhammad entered the outskirts of Medina but did not enter the city directly. He stopped at a place called Quba, some miles from the main city, and established a mosque, which was the first mosque built. After a fourteen-day stay at Quba, Muhammad started for Medina, participating in his first Friday prayer on the way, and upon reaching the city was greeted cordially by its people.

Among the first things Muhammad did to ease the longstanding grievances among the tribes of Medina was draft a document known as the Constitution of Medina, which created a kind of alliance or federation among the eight Medinan tribes and Muslim emigrants from Mecca. The document specified rights and duties of all citizens and the relationship of the different communities in Medina (including between the Muslim community and other communities, specifically the Jews and other People of the Book). The Islamic community, the Ummah, had a religious outlook, also shaped by practical considerations, and substantially preserved the legal forms of the old Arab tribes. The constitution instituted rights and responsibilities and united the different Medina communities into the first Islamic state, the Ummah.

An important feature of the Constitution of Medina is the redefinition of ties between Muslims. It set faith relationships above blood ties and emphasized individual responsibility. Tribal identities were still important and were used to refer to different groups, but the constitution declared that the “main binding tie” for the newly created Ummah was religion. This contrasts with the norms of pre-Islamic Arabia, which was a thoroughly tribal society. This was an important event in the development of the small group of Muslims in Medina to the larger Muslim community and empire. While praying in Medina in 624 CE, Muhammad received revelations that he should be facing Mecca rather than Jerusalem during prayer. Muhammad adjusted to the new direction, and his companions praying with him followed his lead, beginning the tradition of facing Mecca during prayer.

Around 628 CE, the nascent Islamic state was somewhat consolidated when Muhammad left Medina to perform pilgrimage at Mecca. The Quraysh intercepted him enroute and made a treaty with the Muslims. Though the terms of the Hudaybiyyah treaty may have been unfavorable to the Muslims of Medina, the Quran declared it a clear victory. Muslim historians suggest that the treaty mobilized the contact between the Meccan pagans and the Muslims of Medina. The treaty demonstrated that the Quraysh recognized Muhammad as their equal and Islam as a rising power.

8.8.3 The Expansion of Armed Conflict

Economically uprooted by their Meccan persecutors and with no available profession, the Muslim migrants turned to raiding Meccan caravans. This response to persecution and effort to provide sustenance for Muslim families initiated armed conflict between the Muslims and the pagan Quraysh of Mecca. Muhammad delivered Quranic verses permitting the Muslims, “those who have been expelled from their homes,” to fight the Meccans in opposition to persecution. The caravan attacks provoked and pressured Mecca by interfering with trade and allowed the Muslims to acquire wealth, power, and prestige while working toward their ultimate goal of inducing Mecca’s submission to the new faith.

In March 624, Muhammad led three hundred warriors in a raid on a Meccan merchant caravan. The Muslims set an ambush for the caravan at Badr, but a Meccan force intervened, and the Battle of Badr commenced. Although outnumbered more than three to one, the Muslims won the battle, killing at least forty-five Meccans. Muhammad and his followers saw the victory as confirmation of their faith, and Muhammad said the victory was assisted by an invisible host of angels. The victory strengthened Muhammad’s position in Medina and dispelled earlier doubts among his followers.

To maintain economic prosperity, the Meccans needed to restore their prestige after their defeat at Badr. Abu Sufyan, the leader of the ruling Quraysh Tribe, gathered an army of 3,000 men and set out for an attack on Medina. Muhammad led his Muslim force to the Meccans to fight the Battle of Uhud on March 23, 625 CE. When the battle seemed close to a decisive Muslim victory, the Muslim archers left their assigned posts to raid the Meccan camp. Meccan war veteran Khalid ibn al-Walid led a surprise attack, which killed many Muslims and injured Muhammad. The Muslims withdrew up the slopes of Uḥud. The Meccans did not pursue the Muslims further but marched back to Mecca declaring victory. For the Muslims, the battle was a significant setback. According to the Quran, the loss at Uhud was partly a punishment and partly a test for steadfastness.

After eight years of fighting with the Meccan tribes, Muhammad gathered an army of 10,000 Muslim converts and marched on the city of Mecca. The attack went largely uncontested, and Muhammad took over the city with little bloodshed. Most Meccans converted to Islam. Muhammad declared an amnesty for past offenses, except for ten men and women who had mocked and made fun of him in songs and verses. Some of these people were later pardoned. Muhammad destroyed the pagan idols in the Kaaba and then sent his followers out to destroy all of the remaining pagan temples in Eastern Arabia.

At the end of the 10th year after the migration to Medina, Muhammad performed his first truly Islamic pilgrimage, thereby teaching his followers the rules governing the various ceremonies of the annual Great Pilgrimage. In 632, a few months after returning to Medina from the Farewell Pilgrimage, Muhammad fell ill and died. By the time Muhammad died, most of the Arabian Peninsula had converted to Islam, and he had united Arabia into a single Muslim religious polity.

8.8.3 Muhammad’s Successors and the Sunni / Shia Split

After Muhammad’s death in 632 CE, there were conflicts among his followers as to who would become his successor, which created a split in Islam between the Sunni and Shi’a sects.

Muhammad united the tribes of Arabia into a single Arab Muslim religious polity in the last years of his life. He established a new unified Arabian Peninsula, which led to the Rashidun and Umayyad Caliphates and the rapid expansion of Muslim power over the next century. In areas that were previously under Sassanid Persian or Byzantine rule, the Rashidun caliphs lowered taxes, provided greater local autonomy (to their delegated governors), granted greater religious freedom for Jews and some indigenous Christians, and brought peace to peoples demoralized and disaffected by the casualties and heavy taxation that resulted from the decades of Byzantine-Persian warfare.

With Muhammad’s death in 632 CE, disagreement broke out among his followers over deciding his successor. Abu Bakr was confirmed as the first caliph (religious successor to Muhammad) that same year. Once Abu Bakr quelled the rebellions in Arabia, he began a war of conquest. In just a few short decades, his campaigns led to one of the largest empires in history. Muslim armies conquered most of Arabia by 633, followed by north Africa, Mesopotamia, and Persia, significantly shaping the history of the world through the spread of Islam.

However, the choice of Abu Bakr was disputed by some of Muhammad’s companions, who held that Ali ibn Abi Talib, Muhammad’s cousin and son-in-law, had been designated the successor by Muhammad at Ghadir Khumm. Ali would eventually become the fourth Sunni caliph. These disagreements over Muhammad’s true successor led to a major split in Islam between what became the Sunni and Shi’a denominations, a division that still holds to this day.

Sunni Muslims believe and confirm that Abu Bakr was chosen by the community and that this was the proper procedure. Sunnis further argue that a caliph should ideally be chosen by election or community consensus. Shi’a Muslims believe that just as God alone appoints a prophet, only God has the prerogative to appoint the successor to his prophet. They believe God chose Ali to be Muhammad’s successor and the first caliph of Islam.

8.8.4 The Umayyad Caliphate (661–750)

The Umayyad Caliphate, the second of the four major Arab caliphates established after the death of Muhammad, expanded the territory of the Islamic state to one of the largest empires in history. This caliphate was centered on the Umayyad dynasty, hailing from Mecca. The Umayyad family had first come to power under the third caliph, Uthman ibn Affan (r. 644–656), but the Umayyad regime was founded by Muawiya after the end of the First Muslim Civil War in 661 CE. Syria remained the Umayyads’ main power base thereafter, and Damascus was their capital.

Under the Umayyads, the caliphate territory grew rapidly. The Islamic Caliphate became one of the largest unitary states in history and one of the few states to ever extend direct rule over three continents (Africa, Europe, and Asia). The Umayyads incorporated the Caucasus, Transoxiana, Sindh, the Maghreb, and the Iberian Peninsula (Al-Andalus) into the Muslim world. At its greatest extent, the Umayyad Caliphate covered 5.79 million square miles and included 62 million people (29% of the world’s population), making it the fifth largest empire in history in both area and proportion of the world’s population. Although the Umayyad Caliphate did not rule all of the Sahara, nomadic Berber tribes paid homage to the caliph. However, although these vast areas may have recognized the supremacy of the caliph, de facto power was in the hands of local sultans and emirs.

The Umayyad dynasty was not universally supported within the Muslim community for a variety of reasons, including their hereditary election and suggestions of impious behavior. Some Muslims felt that only members of Muhammad’s Banu Hashim clan or those of his own lineage, such as the descendants of Ali, should rule. Some Muslims thought that Umayyad taxation and administrative practices were unjust. While the non-Muslim population had autonomy, their judicial matters were dealt with in accordance with their own laws and by their own religious heads or their appointees. Non-Muslims paid a poll tax for policing to the central state. Muhammad had stated explicitly during his lifetime that each religious minority should be allowed to practice its own religion and govern itself, and the policy had on the whole continued.

There were numerous rebellions against the Umayyads, as well as splits within the Umayyad ranks, which notably included the rivalry between Yaman and Qays. Allegedly, the Sunnis killed Ali’s son Hussein and his family at the Battle of Karbala in 680, solidifying the Shi’a-Sunni split. Eventually, supporters of the Banu Hashim and the supporters of the lineage of Ali united to bring down the Umayyads in 750. However, the Shiʻat ʻAlī, “the Party of Ali,” were again disappointed when the Abbasid dynasty took power, as the Abbasids were descended from Muhammad’s uncle `Abbas ibn `Abd al-Muttalib, not from Ali.

The Abbasid victors desecrated the tombs of the Umayyads in Syria, sparing only that of Umar II, and most of the remaining members of the Umayyad family were tracked down and killed. When Abbasids declared amnesty for members of the Umayyad family, eighty gathered to receive pardons, and all were massacred. One grandson of Hisham, Abd al-Rahman I, survived and established a kingdom in Al-Andalus (Moorish Iberia, today in Spain), proclaiming his family to be the Umayyad Caliphate revived.

Umayyad Dynasty in Cordoba, Spain

The revival of the Umayyad Caliphate in Al-Andalus (what would become modern Spain) was called the Caliphate of Córdoba, which lasted until 1031. The period was characterized by an expansion of trade and culture and saw the construction of masterpieces of al-Andalus architecture.

The caliphate enjoyed increased prosperity during the 10th century. Abd-ar-Rahman III united al-Andalus and brought the Christian kingdoms of the north under control through force and diplomacy. Abd-ar-Rahman stopped the Fatimid advance into caliphate land in Morocco and al-Andalus. This period of prosperity was marked by increasing diplomatic relations with Berber tribes in north Africa, Christian kings from the north, and France, Germany, and Constantinople.

Córdoba was the cultural and intellectual center of al-Andalus. Mosques, such as the Great Mosque, were the focus of many caliphs’ attention. The caliph’s palace, Medina Azahara, was on the outskirts of the city and had many rooms filled with riches from the East. The library of Al-Ḥakam II was one of the largest libraries in the world, housing at least 400,000 volumes, and Córdoba possessed translations of ancient Greek texts into Arabic, Latin, and Hebrew. During the Umayyad Caliphate period, relations between Jews and Arabs were cordial; Jewish stonemasons helped build the columns of the Great Mosque. Al-Andalus was subject to eastern cultural influences as well. The musician Ziryab is credited with bringing hair and clothing styles, toothpaste, and deodorant from Baghdad to the Iberian Peninsula. Advances in science, history, geography, philosophy, and language occurred during the Umayyad Caliphate as well.

Legacy of the Umayyad Caliphate

The Umayyad Caliphate was marked both by territorial expansion and by the administrative and cultural problems that such expansion created. Despite some notable exceptions, the Umayyads tended to favor the rights of the old Arab families and their own over those of newly converted Muslims (mawali). Therefore, they held to a less universalist conception of Islam than did many of their rivals.

During the period of the Umayyads, Arabic became the administrative language, in which state documents and currency were issued. Mass conversions brought a large influx of Muslims to the caliphate. The Umayyads also constructed famous buildings such as the Dome of the Rock at Jerusalem and the Umayyad Mosque at Damascus.

According to one common view, the Umayyads transformed the caliphate from a religious institution (during the Rashidun) to a dynastic one. However, the Umayyad caliphs saw themselves as the representatives of God on Earth.

The Umayyads have met with a largely negative reception from later Islamic historians, who have accused them of promoting a kingship (mulk, a term with connotations of tyranny) instead of a true caliphate (khilafa). In this respect, it is notable that the Umayyad caliphs referred to themselves not as khalifat rasul Allah (“successor of the messenger of God,” the title preferred by the tradition) but rather as khalifat Allah (“deputy of God”).

Many Muslims criticized the Umayyads for having too many non-Muslim, former Roman administrators in their government. St. John of Damascus was also a high administrator in the Umayyad administration. As the Muslims took over cities, they left the people’s political representatives and the Roman tax collectors and administrators. The people’s political representatives calculated and negotiated taxes. The central government and the local governments were paid respectively for the services they provided. Many Christian cities used some of the taxes to maintain their churches and run their own organizations. Later, some of the Muslims criticized the Umayyads for not reducing the taxes of the people who converted to Islam.

8.9 THE SPREAD OF ISLAM

In the years following the Prophet Muhammad’s death, the expansion of Islam was carried out by his successor caliphates, who increased the territory of the Islamic state and sought converts from both polytheistic and monotheistic religions.

The expansion of the Arab Empire in the years following the Prophet Muhammad’s death led to the creation of caliphates occupying a vast geographical area. Conversion to Islam was boosted by missionary activities, particularly those of Imams, or prayer leaders, who easily intermingled with local populace to propagate religious teachings. These early caliphates, coupled with Muslim economics and trading and the later expansion of the Ottoman Empire, resulted in Islam’s spread outwards from Mecca towards both the Atlantic and Pacific oceans and the creation of the Muslim world. Trading played an important role in the spread of Islam in several parts of the world, notably southeast Asia.

Muslim dynasties were soon established, and subsequent empires such as those of the Abbasids, Fatimids, Almoravids, Seljukids, Ajurans, Adal, and Warsangali in Somalia, Mughals in India, Safavids in Persia, and Ottomans in Anatolia were among the largest and most powerful in the world. The people of the Islamic world created numerous sophisticated centers of culture and science with far-reaching mercantile networks, travelers, scientists, hunters, mathematicians, doctors, and philosophers, all contributing to the Golden Age of Islam. Islamic expansion in South and East Asia fostered cosmopolitan and eclectic Muslim cultures in the Indian subcontinent, Malaysia, Indonesia, and China.

Within the first century of the establishment of Islam upon the Arabian Peninsula and the subsequent rapid expansion of the Arab Empire during the Muslim conquests, one of the most significant empires in world history was formed. For the subjects of this new empire, formerly subjects of the greatly reduced Byzantine and obliterated Sassanid empires, not much changed in practice. The objective of the conquests was of a practical nature more than anything else, as fertile land and water were scarce in the Arabian Peninsula. A real Islamization therefore only came about in the subsequent centuries.

8.9.1 Policy Toward Non-Muslims

The Arab conquerors did not repeat the mistake made by the Byzantine and Sasanian empires, who had tried and failed to impose an official religion on subject populations, which had caused resentments that made the Muslim conquests more acceptable to them. Instead, the rulers of the new empire generally respected the traditional Middle-Eastern pattern of religious pluralism, which was one not of equality but rather of dominance by one group over the others. After the end of military operations, which involved the sacking of some monasteries and confiscation of Zoroastrian fire temples in Syria and Iraq, the early caliphate was characterized by religious tolerance, and people of all ethnicities and religions blended in public life. Before Muslims were ready to build mosques in Syria, they accepted Christian churches as holy places and shared them with local Christians. In Iraq and Egypt, Muslim authorities cooperated with Christian religious leaders. Numerous churches were repaired and new ones built during the Umayyad era.

Some non-Muslim populations did experience persecution, however. After the Muslim conquest of Persia, Zoroastrians were given dhimmi (non-Muslim) status and subjected to persecutions; discrimination and harassment began in the form of sparse violence. Zoroastrians were made to pay an extra tax called Jizya; if they failed, they were killed, enslaved, or imprisoned. Those paying Jizya were subjected to insults and humiliation by the tax collectors. Zoroastrians who were captured as slaves in wars were given their freedom if they converted to Islam.

8.10 THE ISLAMIC GOLDEN AGE

Abbasid leadership cultivated intellectual, cultural, and scientific developments in the Islamic Golden Age. The Islamic Golden Age refers to a period in the history of Islam, traditionally dated from the 8th century to the 13th century, during which much of the historically Islamic world was ruled by various caliphates and science, economic development, and cultural works flourished. This period is traditionally understood to have begun during the reign of the Abbasid caliph Harun al-Rashid (786–809) with the inauguration of the House of Wisdom in Baghdad, where scholars from various parts of the world with different cultural backgrounds were mandated to gather and translate the world’s classical knowledge into the Arabic language.

The end of the age is variously given as 1258 with the Mongolian Sack of Baghdad or 1492 with the completion of the Christian Reconquista of the Emirate of Granada in Al-Andalus, Iberian Peninsula. During the Golden Age, the major Islamic capital cities of Baghdad, Cairo, and Córdoba became the main intellectual centers for science, philosophy, medicine, and education. The government heavily patronized scholars, and the best scholars and notable translators, such as Hunayn ibn Ishaq, had salaries estimated to be the equivalent of those of professional athletes today.

The School of Nisibis and later the School of Edessa became centers of learning and transmission of classical wisdom. The House of Wisdom was a library, translation institute, and academy, and the Library of Alexandria and the Imperial Library of Constantinople housed new works of literature. Nestorian Christians played an important role in the formation of Arab culture, with the Jundishapur hospital and medical academy prominent in the late Sassanid, Umayyad, and early Abbasid periods.

8.10.1 Literature and Philosophy

Christians (particularly Nestorian Christians) contributed to the Arab Islamic civilization during the Umayyad and the Abbasid periods by translating works of Greek philosophers to Syriac and then to Arabic. During the 4th through the 7th centuries, scholarly work in the Syriac and Greek languages was either newly initiated or carried on from the Hellenistic period. Many classic works of antiquity might have been lost if Arab scholars had not translated them into Arabic and Persian and later into Turkish, Hebrew, and Latin. Islamic scholars also absorbed ideas from China and India, and in turn, Arabic philosophic literature contributed to the development of modern European philosophy.

With the introduction of paper, information was democratized, and it became possible to make a living from simply writing and selling books. The use of paper spread from China into Muslim regions in the 8th century, then to Spain (and then the rest of Europe) in the 10th century. Paper was easier to manufacture than parchment and less likely to crack than papyrus and could absorb ink, making it difficult to erase and ideal for keeping records. Islamic paper makers devised assembly-line methods of hand-copying manuscripts to turn out editions far larger than any available in Europe for centuries. The best-known fiction from the Islamic world is The Book of One Thousand and One Nights, which took form in the 10th century and reached its final form by the 14th century, although the number and type of tales vary.

Ibn Rushd, also known by his Latinized name Averroës (April 14, 1126–December 10, 1198), was an Al-Andalus Muslim polymath, a master of Aristotelian philosophy, Islamic philosophy, Islamic theology, Maliki law and jurisprudence, logic, psychology, politics, Andalusian classical music theory, medicine, astronomy, geography, mathematics, physics, and celestial mechanics. Averroes was born in Córdoba, Al-Andalus, present-day Spain, and died in Marrakesh, present-day Morocco.

The 13th-century philosophical movement based on Averroes’ work is called Averroism. Both Ibn Rushd and the scholar Ibn Sina played a major role in saving the works of Aristotle, whose ideas came to dominate the non-religious thought of the Christian and Muslim worlds. Ibn Rushd has been described as the “founding father of secular thought in Western Europe.” He tried to reconcile Aristotle’s system of thought with Islam. According to him, there is no conflict between religion and philosophy; rather, they are different ways of reaching the same truth. He believed in the eternity of the universe. Ibn Ruhd also held that the soul is divided into two parts, one individual and one divine; while the individual soul is not eternal, all humans at the basic level share one and the same divine soul.

8.8.2 Science, Mathematics, and Medicine

The Arabs assimilated the scientific knowledge of the civilizations they had conquered, including the ancient Greek, Roman, Persian, Chinese, Indian, Egyptian, and Phoenician civilizations. Scientists recovered the Alexandrian mathematical, geometric, and astronomical knowledge, such as that of Euclid and Claudius Ptolemy.

Persian scientist Muhammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī significantly developed algebra in his landmark text Kitab al-Jabr wa-l-Muqabala, from which the term “algebra” is derived. The term “algorithm” is derived from the name of the scholar al-Khwarizmi, who was also responsible for introducing the Arabic numerals and Hindu-Arabic numeral system beyond the Indian subcontinent. In calculus, the scholar Alhazen discovered the sum formula for the fourth power, using a method readily generalizable to determine the sum for any integral power. He used this to find the volume of a paraboloid.

Medicine was a central part of medieval Islamic culture. Responding to circumstances of time and place, Islamic physicians and scholars developed a large and complex medical literature exploring and synthesizing the theory and practice of medicine. Islamic medicine was built on tradition, chiefly the theoretical and practical knowledge developed in India, Greece, Persia, and Rome. Islamic scholars translated their writings from Syriac, Greek, and Sanskrit into Arabic and then produced new medical knowledge based on those texts. In order to make the Greek tradition more accessible, understandable, and teachable, Islamic scholars organized the Greco-Roman medical knowledge into encyclopedias.

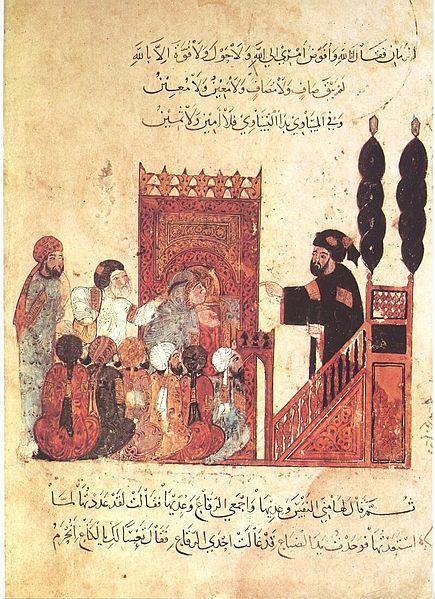

8.8.2 Art

Ceramics, glass, metalwork, textiles, illuminated manuscripts, and woodwork flourished during the Islamic Golden Age. Manuscript illumination became an important and greatly respected art, and portrait miniature painting flourished in Persia. Calligraphy, an essential aspect of written Arabic, developed in manuscripts and architectural decoration.

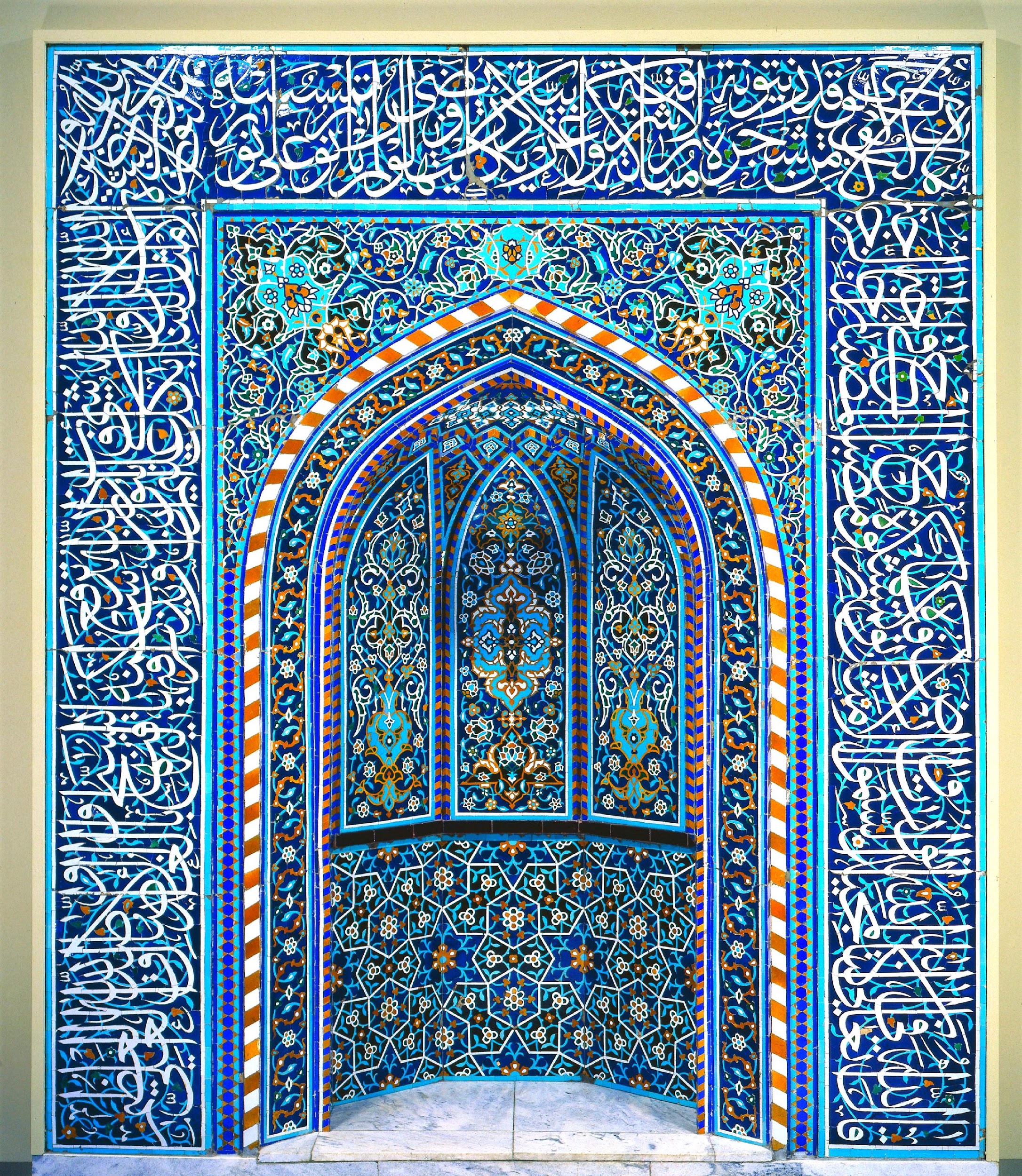

Typically, though not entirely, Islamic art depicts nature patterns and Arabic calligraphy, rather than figures, because many Muslims feared that the depiction of the human form is idolatry and thereby a sin against God, forbidden in the Quran. There are repeating elements in Islamic art, such as the use of geometrical floral or vegetal designs in a repetition known as the arabesque. The arabesque in Islamic art is often used to symbolize the transcendent, indivisible, and infinite nature of God. Mistakes in repetitions may be intentionally introduced as a show of humility by artists who believe only God can produce perfection, although this theory is disputed.

The traditional instrument of the Arabic calligrapher is the qalam, a pen made of dried reed or bamboo. Qalam ink is often in color and chosen such that its intensity can vary greatly, so that the greater strokes of the compositions can be very dynamic in their effect. Islamic calligraphy is applied on a wide range of decorative mediums other than paper, such as tiles, vessels, carpets, and inscriptions. Before the advent of paper, papyrus and parchment were used for writing.

By the 10th century, the Persians, who had converted to Islam, began weaving inscriptions on elaborately patterned silks. These calligraphic-inscribed textiles were so precious that Crusaders brought them to Europe as prized possessions. A notable example is the Suaire de Saint-Josse, used to wrap the bones of St. Josse in the abbey of St. Josse-sur-Mer near Caen in northwestern France.

There were many advances in architectural construction, and mosques, tombs, palaces, and forts were inspired by Persian and Byzantine architecture. Islamic mosaic art anticipated principles of quasicrystalline geometry, which would not be discovered for 500 more years. This art used symmetric polygonal shapes to create patterns that can continue indefinitely without repeating. These patterns have even helped modern scientists understand quasicrystals at the atomic levels.

8.11 THE LATER EMPIRES

8.11.1 The Abbasid Empire (c. 750 CE)

The Abbasid Caliphate was the third of the Islamic caliphates to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad in 750 CE and ruled over a large, flourishing empire for three centuries. The Umayyad dynasty was overthrown by another family of Meccan origin, the Abbasids, in 750 CE. The Abbasids distinguished themselves from the Umayyads by attacking their moral character and administration. In particular, they appealed to non-Arab Muslims, known as mawali, who remained outside the kinship-based society of the Arabs and were perceived as a lower class within the Umayyad empire. The Abbasid dynasty descended from Muhammad’s youngest uncle, Abbas ibn Abd al-Muttalib (566–653 CE), from whom the dynasty takes its name. Muhammad ibn ‘Ali, a great-grandson of Abbas, began to campaign for the return of power to the family of Muhammad, the Hashemites, in Persia during the reign of Umar II, an Umayyad caliph who ruled from 717 to 720 CE.

The Abbasids moved the empire’s capital from Damascus, in modern-day Syria, to Baghdad, in modern-day Iraq, in 762 CE. The Abbasids had depended heavily on the support of Persians in their overthrow of the Umayyads, and the geographic power shift appeased the Persian mawali support base. Abu al-‘Abbas’s successor, Al-Mansur, welcomed non-Arab Muslims to his court. While this helped integrate Arab and Persian cultures, it alienated the Arabs who had supported the Abbasids in their battles against the Umayyads. The Abbasids established the new position of vizier to delegate central authority and delegated even greater authority to local emirs. As the viziers exerted greater influence, many Abbasid caliphs were relegated to a more ceremonial role as Persian bureaucracy slowly replaced the old Arab aristocracy.

The Abbasids, who ruled from Baghdad, had an unbroken line of caliphs for over three centuries, consolidating Islamic rule and cultivating great intellectual and cultural developments in the Middle East in the Golden Age of Islam. By 940 CE, however, the power of the caliphate under the Abbasids began waning as non-Arabs gained influence and the various subordinate sultans and emirs became increasingly independent.

The Abbasid leadership worked to overcome the political challenges of a large empire with limited communication in the last half of the 8th century (750–800 CE). While the Byzantine Empire was fighting Abbasid rule in Syria and Anatolia, the caliphate’s military operations were focused on internal unrest. Local governors had begun to exert greater autonomy, using their increasing power to make their positions hereditary. Simultaneously, former supporters of the Abbasids had broken away to create a separate kingdom around Khorasan in northern Persia.

Several factions left the empire to exercise independent authority. In 793 CE, the Shi’a (also called Shi’ite) dynasty of Idrisids gained authored over Fez in Morocco. The Berber Kharijites set up an independent state in North Africa in 801 CE. A family of governors under the Abbasids became increasingly independent until they founded the Aghlabid Emirate in the 830s. Within 50 years, the Idrisids in the Maghreb, the Aghlabids of Ifriqiya, and the Tulunids and Ikshidids of Misr became independent in Africa.

By the 860s, governors in Egypt set up their own Tulunid Emirate, so named for its founder Ahmad ibn Tulun, starting a dynastic rule separate from the caliph. In the eastern territories, local governors decreased their ties to the central Abbasid rule. The Saffarids of Herat and the Samanids of Bukhara seceded in the 870s to cultivate a more Persian culture and rule. The Tulunid dynasty managed Palestine, the Hijaz, and parts of Egypt. By 900 CE, the Abbasids controlled only central Mesopotamia, and the Byzantine Empire began to reconquer western Anatolia.

8.11.2 The Fatimid Caliphate (909–1171 CE)

Several factions challenged the Abbasids’ claims to the caliphate. Most Shi’a Muslims had supported the Abbasid war against the Umayyads because the Abbasids claimed legitimacy with their familial connection to Muhammad, an important issue for Shi’a. However, once in power, the Abbasids embraced Sunni Islam and disavowed any support for Shi’a beliefs.

The Shiʻa Ubayd Allah al-Mahdi Billah of the Fatimid dynasty, who claimed descent from Muhammad’s daughter, declared himself Caliph in 909 CE and created a separate line of caliphs in North Africa. The Fatimid caliphs initially controlled Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, and Libya, and they expanded for the next 150 years, taking Egypt and Palestine. The Abbasid dynasty finally challenged Fatimid rule, limiting them to Egypt. By the 920s, a Shi’a sect that only recognized the first five Imams and could trace its roots to Muhammad’s daughter Fatima took control of Idrisi and then Aghlabid domains. This group advanced to Egypt in 969 CE, establishing their capital near Fustat in Cairo, which they built as a bastion of Shi’a learning and politics. By 1000 CE, they had become the chief political and ideological challenge to Abbasid Sunni Islam. At this point, the Abbasid dynasty had fragmented into several governorships that were mostly autonomous, although they official recognized caliphal authority from Baghdad. The caliph himself was under “protection” of the Buyid Emirs, who possessed all of Iraq and western Iran and were quietly Shi’a in their sympathies.

Outside Iraq, all the autonomous provinces slowly became states with hereditary rulers, armies, and revenues. They operated under only nominal caliph authority, with emirs ruling their own provinces from their own capitals. Mahmud of Ghazni took the title of “sultan,” instead of “emir,” signifying the Ghaznavid Empire’s independence from caliphal authority, despite Mahmud’s ostentatious displays of Sunni orthodoxy and ritual submission to the caliph. In the 11th century, the loss of respect for the caliphs continued, as some Islamic rulers no longer mentioned the caliph’s name in the Friday khutba or struck it off their coinage. The political power of the Abbasids largely ended with the rise of the Buyids and the Seljuq Turks in 1258 CE. Though lacking in political power, the dynasty continued to claim authority in religious matters until after the Ottoman conquest of Egypt in 1517.

They also founded the new city of Cairo, rather than contend with older, possibly rebellious cities like Alexandria. Cairo developed into the preeminent cultural and economic center of the Islamic world, taking over from a Baghdad in decline.

8.12 THE CRUSADES

In 1095, Urban II launched the first crusade from Clermont, a city in southern France. He had benefited from recent church reforms, renewed religious fervor, and a concomitant increase in papal power. While traveling through France, he made an argument for the recovery of the Holy Land: because it belonged to Jesus, it should be controlled by his followers. He also appealed to the greatness of the Franks, promising potential pilgrims a land flowing with milk, honey, and riches. And he offered them well-designed spiritual rewards. For example, salvation applied to those who died on campaign, and anyone who invested in a crusade secured themselves a place in heaven.

The Crusades started in 1096 and were part of a larger process whereby Muslims ceded territory to non-Muslims, sometimes permanently. Provoked by al-Hakim’s treatment of Christians in the Holy Land, as well as the Turkic invasion of Anatolia, Europeans commenced several centuries’ worth of armed crusades against the Muslim states of the eastern Mediterranean and North Africa. Save for the first crusade, in which the Christians established the Crusader states of Edessa, Antioch, Tripoli, and the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem, all of their campaigns ended in disaster. In fact, they were either looting expeditions or responses to the loss of Crusader states to Muslims. The success that the Latin knights did enjoy related to not only the political fragmentation of the Seljuqs in the eastern Mediterranean but also the general disinterest of the Fatimid Caliphate in Egypt, which had been dealing with both the repercussions of a religious schism and the consequences of famine and plague. Slow to respond to the challenge posed by the Christians, the Fatimids watched the Crusaders from afar with indifference.

The Muslim counterattack eventually came under the direction of Salah al-Din (Saladin) (d. 1193), a unifier of various Muslim factions in the eastern Mediterranean. An ethnic Kurd, he hailed from a family of soldiers of fortune in the employ of the Zengid Dynasty’s Nur al-Din, a vassal of the Seljuq Turks. Salah al-Din set off in his twenties to fight battles for his uncle, Shirkuh, a Zengid general. A dynamic leader and tactician, he helped his uncle dispatch with the Fatimid opposition in Egypt and solidified Nur al-Din’s rule there. His uncle dying soon thereafter, Salah al-Din eventually became the vizier, or senior minister, to Nur al-Din in 1169. For five years, Salah al-Din ruled Egypt on behalf of Nur al-Din. Then Nur al-Din died in Damascus in 1174, leaving no clear successor.

8.12.1 The Ayyubid Sultanate

In the absence of a formal heir to Nur al-Din, Salah al-Din established the Ayyubid Dynasty (1171–1260), named after his father, Ayyub, a provincial governor for the Zengid Dynasty, a family of Oghuz Turks who served as vassals of the Seljuq Empire. Once in power, Salah al-Din established a Sunni government and insisted that the mosque of al-Azhar preach his brand of Islam. He used the concept of jihad to unify the Middle East under the banner of Islam in order to defeat the Christians, but he did not principally direct jihad towards them. A champion of Sunni Islam, he believed that his religion was being threatened mainly from within by the Shi‘a. Like most of their predecessors, the Ayyubids also benefited from tribal ‘asabiyah, or dynastic consensus. Ayyubid ‘asabiyah included a Kurdish heritage, as well as a strong desire to return to Sunni orthodoxy. It was as champions of Sunni Islam that they purposely recruited leading Muslim scholars from abroad, ultimately culminating in Egypt becoming the preeminent state in the Islamic world.

Initially, Salah al-Din displayed no particular interest in the Crusader states. He had clashed with the Crusaders and King Baldwin IV of Jerusalem; also, Raynald de Chântillon even had handed him a rare defeat at the Battle of Montgisard in 1177. But the Crusaders ultimately brokered an armistice with Salah al-Din. Eventually, Raynald broke their truce when he started attacking Muslim pilgrims and trade caravans in the 1180s. Ensuing skirmishes between the forces of Salah al-Din and Guy de Lusignan, the new King of Jerusalem, presaged a forthcoming battle. In 1187, the two sides met near Tiberias, in modern-day Israel. Salah al-Din intentionally attacked the fortress of Tiberius in order to lure the Crusaders away from their well-watered stronghold. His plan worked, and the Christians quickly ran out of water. On the night before the battle, Salah al-Din set brush fires to exacerbate their thirst. He coerced the parched Latin knights down through the Horns of Hattin towards the cool waters of Lake Tiberius. Salah al-Din bottlenecked the Crusader forces, with the double hill of Hattin acting as a choke point.

The Battle of Hattin represented a smashing victory for Salah al-Din and a major loss for the Crusaders. Tradition dictated that Salah al-Din hold most of the leaders for ransom. Unlike the Crusaders, he treated the defenders of cities with understanding. He showed tolerance of minorities and even established a committee to partition Jerusalem amongst all the interested religious groups. In this way, he proved his moral superiority to the Crusaders.

With most of their important leaders either killed in battle or captured, no unified Christian leadership remained to fight against Salah al-Din. Deprived of the backbone of their organization, the Crusaders were left with only a few defenseless fortresses along the coast. Salah al-Din pressed his advantage. Increasingly isolated and relying on ever dwindling numbers of Latin Christians willing to remain permanently in the Holy Land, the Latin Crusaders were eventually expelled from the region in 1291.

Although Salah al-Din had maintained direct control over Egypt, he intentionally distributed control over wide swaths of the empire to loyal vassals and family members, whose governance became increasingly autonomous from Cairo. Salah al-Din’s sons and grandsons, who did not have the same ability as their forefather, had trouble managing an increasingly decentralized empire. Widespread mamluk factionalism and family disputes over the control of territory contributed to the weakening of the sultanate.

In this vacuum of power, the mamluks, a former Turkish slave caste of Egypt, came to the fore.

8.13 THE MAMLUK SULTANATE

The year was 1249, and Louis IX’s seventh crusade had just gotten underway when as-Salih, the last Ayyubid ruler, took to his deathbed. Under the eminent threat of a Crusader invasion, Shajar al-Durr, a Turkish concubine, agreed to take over the reins of government until her son, Turanshah, could assert himself. While mamluks did not possess a tribal ‘asabiyah in the traditional sense, they did constitute a proud caste of elite warriors who had an exaggerated sense of group solidarity. As a social group, their former status as slaves provided them with enough group cohesion to overthrow the Ayyubids.

Shajar al-Durr saw herself as another Cleopatra and wanted to rule in her own right. In 1257, in an effort to avoid a power struggle, Shajar al-Durr had her husband, Aybak, strangled and claimed that he had died a natural death. Not long thereafter, Aybak’s fifteen year old son, al-Mansur ‘Ali, had Shajar al-Durr stripped and beaten to death. He reigned as sultan for two years until Qutuz, a leading mamluk, deposed him, as he thought the sultanate needed a strong and capable ruler to deal with the looming Mongol threat.

The Mamluk Sultanate appeared to be on a collision course with Hulagu’s Ilkhanate, one of Mongol Empire’s four khanates, whose forces were advancing through the Mamluk-held Levant. Then in the summer of 1260, the Great Khan Möngke died, and Hulagu returned home with the bulk of his forces to participate in the required khuriltai, or Mongol assembly, perhaps expecting to be elected the next Great Khan. Hulagu left his general Kitbuqa behind with a smaller army to fight the Mamluks. In July of that year, a confrontation took place at Ayn Jalut, near Lake Tiberias. During the ensuing battle, the Mamluk General Baybars drew out the Mongols with a feigned retreat. Hiding behind a hill, Aybak’s mamluk heavy cavalrymen ambushed the unsuspecting Mongols and defeated them in close combat, securing a rare victory over the Mongols. The Mamluks captured and executed Kitbuqa and forced the remnants of the Mongol forces to retreat. Just days after their signal victory over the Mongols, Baybars (1260–1277) murdered Qutuz, continuing a pattern of rule in which only the strongest Mamluk rulers could survive. The fourteenth and fifteenth centuries witnessed the decline of the Mamluk Empire. Several internal and external factors help explain their decline. Domestically, the Black Death ravaged Egypt for years. In fact, it continued in North Africa longer than it did in Europe. This plague caused economic disruption in the sultanate. With fewer people available, labor, or human capital, became much more expensive. Further, plague-related inflation destabilized the economy, as the value of goods and services also rose. The mamluks responded to inflationary pressures by increasing taxes, but their revenue from those taxes actually decreased. This decrease made it difficult for the mamluks to maintain their irrigation networks, and without irrigation, agricultural productivity decreased.

Externally, plague was not the only cause of inflation. Columbus’s discovery of the New World began a process in which gold began filtering through Europe and into North Africa. Egypt’s weak economy could not absorb this massive influx of money, thus causing more inflation. New trade routes, like the one pioneered by Vasco de Gama, offered Europeans direct sea routes to Asia. No longer was Egypt the middleman for long-distance trade between Europe and Asia, thereby losing out on valuable revenue from tariffs. The profits from commerce transferred to the ascending states of Portugal and Spain. With the defeat of the Mamluks in the Ottoman–Mamluk War of 1516–1517, the stage was set for the rise of the Ottomans.

8.14 CONCLUSION

A contemporary historian who served the Mamluk Sultanate, Ibn Khaldun astutely recognized the applicability of his Cyclical Theory of History to the evolution of Islamic history during the period covered in this chapter. By the eighth century, Islam became the predominant social and political unifier of the Middle East. And for the next nine hundred years, various caliphates used family and religion as tools to rule the region. However, these caliphates faced religiously-inspired revolts that challenged their authority. Quelling these revolts weakened the regimes, often leading to greater decentralization and the fragmentation of empires. Into these vacuums of power, new families armed with tribal ‘asabiyah and a novel religious ideology came forth to supplant a once dominant group who had succumbed to the wiles of civilization and whose influence gradually waned in the face of insurgent desert peoples.

8.15 WORKS CONSULTED AND FURTHER READING

Berkey, Jonathan P., The Formation of Islam: Religion and Society in the Near East 600–800. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

Donner, Fred, The Early Islamic Conquests. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1981. Esposito, John L., Islam: The Straight Path. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Halm, Heinz, The Empire of the Mahdi: The rise of the Fatimids. Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1997. Lassner, Jacob, The Shaping of Abbasid Rule. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1980.

Kennedy, Hugh, The Prophet and the Age of the Caliphates: The Islamic Near East from the Sixth to the Eleventh Century. London: Longman, 2004.

Lewis, Bernard, The Arabs in History. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993.

Momen, Moojan, An Introduction to Shi‘i Islam. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1985.

Powell, James M., ed. Muslims Under Latin Rule, 1100–1300. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1990.

Watt, W. Mongomery, Muhammad: Prophet and Statesman. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1974.

Watterson, James. Who Were the Mamluks? History Today, September 5, 2018.

8.16 LINKS TO PRIMARY SOURCES

Ancient Accounts of Arabia 430 BCE–550 CE

https://legacy.fordham.edu/halsall/ancient/arabia1.asp

Ibn Ishaq (d. c. 773 CE): Selections from the Life of Muhammad

https://legacy.fordham.edu/halsall/source/muhammadi-sira.asp

The Prophet Muhammad: Last Sermon

https://legacy.fordham.edu/halsall/source/muhm-sermon.asp

Muhammad Speaks of Allah

http://www.mircea-eliade.com/from-primitives-to-zen/040.html

Muhammad’s Call

http://www.mircea-eliade.com/from-primitives-to-zen/231.html

Muhammad is the Messenger of God

http://www.mircea-eliade.com/from-primitives-to-zen/232.html

Muhammad Proclaims the Prescriptions of Islam

http://www.mircea-eliade.com/from-primitives-to-zen/122.html

The Sunnah, (traditions of the Prophet Muhammad), excerpts

https://legacy.fordham.edu/halsall/source/sunnah-horne.asp

Abu Hamid al-Ghazali (1058–1111 CE): The Remembrance of Death and the Afterlife

https://legacy.fordham.edu/halsall/source/alghazali.asp

The Battle of Badr, 624 CE

http://web.archive.org/web/19980119194508/http://www.islaam.com/ilm/battleof.htm

Al-Baladhuri: The Battle of The Yarmuk (636 CE) and After

https://legacy.fordham.edu/halsall/source/yarmuk.asp

Accounts of the Arab Conquest of Egypt, 642 CE

https://legacy.fordham.edu/halsall/source/642Egypt-conq2.asp

Yakut: Baghdad under the Abbasids, c. 1000 CE

https://legacy.fordham.edu/halsall/source/1000baghdad.asp

Abul Hasan Ali Al-Masu’di (Masoudi) (c. 895?–957 CE): The Book of Golden Meadows, c. 940 CE

https://legacy.fordham.edu/halsall/source/masoudi.asp

The Seven Voyages of Sinbad the Sailor story from the Thousand and One Nights

http://www.sacred-texts.com/neu/lang1k1/tale15.htm

Ibn Rushd (Averroës) (1126–1198 CE): Religion & Philosophy, c. 1190 CE.

https://legacy.fordham.edu/halsall/source/1190averroes.asp

Firdausi: The Epic of Kings, c. 1000 CE

http://classics.mit.edu/Ferdowsi/kings.html

Sa’di (1184–1292 CE): Gulistan, 1258 CE

http://classics.mit.edu/Sadi/gulistan.html