Chapter 7: Western Europe and Byzantium circa 500–1000 CE

Andrew Reeves

7.1 CHRONOLOGY

| Chronology | Western Europe and Byzantium |

|---|---|

| 410 CE | Roman army abandons Britain |

| 476 CE | The general Odavacar deposes last Western Roman emperor |

| 496 CE | The Frankish king Clovis converts to Christianity |

| 636 CE | Arab Muslims defeat the Byzantine army at the Battle of Yarmouk |

| 711 CE | Muslims from North Africa conquer Spain, end of the Visigothic kingdom |

| 717–718 CE | Arabs lay siege to Constantinople but are unsuccessful |

| 732 CE | King Charles Martel of the Franks defeats a Muslim invasion of the kingdom at the Battle of Tours |

| 751 CE | Pepin the Short of the Franks deposes the last Merovingian king and becomes king of the Franks |

| c. 780–840 CE | The Carolingian Renaissance |

| 793 CE | Viking raids begin |

| 800 CE | Charlemagne crowned Roman emperor by Pope Leo III |

| 830 CE | Abbasid caliph Al-Mamun founds the House of Wisdom in Baghdad |

| 843 CE | In the Treaty of Verdun, Charlemagne’s three sons, Lothar, Louis, and Charles the Bald, divide his empire among themselves |

| c. 843–900 CE | Macedonian Renaissance |

| Mid-800s CE | Cyril and Methodius preach Christianity to the Slavic peoples |

| 867 CE | Basil I murders the reigning Byzantine emperor and seizes control of the Empire |

| 871–899 CE | Alfred the Great is king of England. He defeats Norse raiders and creates a consolidated kingdom. |

| 899 CE | Defeated by the Pechenegs, the Magyars begin moving into Central Europe |

| 955 CE | Otto the Great, king of East Francia, defeats the Magyars in battle |

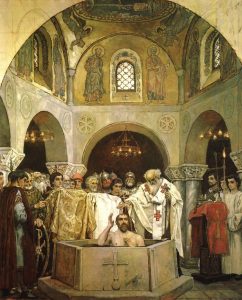

| 988 CE | Vladimir, Grand Prince of Kiev, converts to Christianity |

7.2 INTRODUCTION

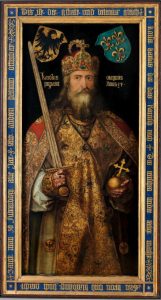

It was Christmas Day in Rome in the year 800 CE. The cavernous interior of St. Peter’s Church smelled faintly of incense. Marble columns lined the open space of the nave, which was packed with the people of Rome. At the eastern end of the church, which was the most prestigious in Western Europe, King Charles of the Franks knelt before the pope. A tall man when standing, the Frankish king had an imposing presence even on his knees. He wore the dress of a Roman patrician: a tunic of multi-colored silk, embroidered trousers, and a richly embroidered cloak clasped with a golden brooch at his shoulder. As King Charles knelt, the pope placed a golden crown, set with pearls and precious stones of blue, green, and red, on the king’s head. He stood to his full height of six feet and the people gathered in the church cried out, “Hail Charles, Emperor of Rome!” The inside of the church filled with cheers. For the first time in three centuries, the city of Rome had an emperor. Outside of the church, the city of Rome itself told a different story. The great circuit of walls built in the third century by the emperor Aurelian still stood as a mighty bulwark against attackers. Much of the land within those walls, however, lay empty. Although churches of all sorts could be found throughout the city, pigs, goats, and other livestock roamed through the open fields and streets of a city retaining only the faintest echo of its earlier dominance of the whole of the Mediterranean world. Where once the Roman forum had been a bustling market, filled with merchants from as far away as India, now the crumbling columns of long-abandoned temples looked out over a broad, grassy field where shepherds grazed their flocks.

The fountains that had once given drinking water to millions of inhabitants now went unused and choked with weeds. The once great baths that had echoed with the lively conversation of thousands of bathers stood only as tumbled-down piles of stone that served as quarries for the men and women who looked to repair their modest homes. The Coliseum, the great amphitheater that had rung with the cries of Rome’s bloodthirsty mobs, was now honeycombed with houses built into the tunnels that had once admitted crowds to the games in the arena.

And yet within this city of ruins, a new Rome sprouted from the ruins of the old. Just outside the city walls and across the Tiber River, St. Peter’s Basilica rose as the symbol of Peter, prince of the Apostles. The golden-domed Pantheon still stood, now a church of the Triune God rather than a temple of the gods of the old world. And, indeed, all across Western Europe, a new order had arisen on the wreck of the Roman state. Although this new order in many ways shared the universal ideals of Rome, its claims were even grander, for it rested upon the foundations of the Christian faith, which claimed the allegiance of all people. How this post-Roman world had come about is the subject to which we shall turn.

Ever since the fifteenth century, historians of Europe have referred to the period between the fall of the Western Roman Empire and the Italian Renaissance (which took place in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries) as the Middle Ages. The term has problems, but it is still useful because it demonstrates that Europe was undergoing a transitional period: it stood between, in the middle of, those times that we call “modern” (after 1500 CE) and what we call the ancient world (up to around 500 CE). This Middle Age would see a new culture grow up that combined elements of Germanic culture, Christianity, and remnants of Rome. It is to the political remnants of Rome that we first turn.

7.3 QUESTIONS TO GUIDE YOUR READING

- How did the Germanic peoples of Western Europe relate to the former Roman territories over which they had taken control?

- Which of Justinian’s policies had the longest-lasting effects?

- What crises did the Byzantine Empire face during the reign of Heraclius?

- What was a way that the Byzantine state reorganized itself to face the challenges of seventh- and eighth-century invasions?

- Why did the Iconoclast emperors believe that using images in worship was wrong?

- How did the Church provide a sense of legitimacy to the kings of the Franks?

- How did the majority of people in Europe and the Byzantine Empire live in the early Middle Ages (i.e., c. 500 to 1000 CE)?

- How did East Francia and England respond to Viking attacks?

7.4 KEY TERMS

- Al-Andalus

- Alcuin of York

- Anglo-Saxons

- Avars

- Balkans

- Battle of Tours

- Body of Civil Law/Justinian Code

- Bulgars

- Byzantine Empire/Byzantium

- Carolingians

- Carolingian Renaissance

- Cathedral church

- Charlemagne

- Charles Martel

- Constantinople

- Cyrillic

- Demonetize

- Dependent farmers

- Donation of Constantine

- Eastern Orthodox

- Exarch

- Hagia Sophia

- Iconoclast Controversy

- Icon

- Iconoclasts

- Iconophiles

- Idolatry

- Kyivan Rus

- Lateran

- Liturgy

- Lombards

- Macedonian Dynasty

- Mayor of the Palace/Major Domo

- Merovingians

- Ostrogoths

- Papal States

- Pillage and gift

- Pope

- Romance languages

- Ruralization

- Rus

- Scriptorium

- Slavs

- Slavonic

- Themes

- Vandals

- Vikings

- Visigoths

7.5 SUCCESSOR KINGDOMS TO THE WESTERN ROMAN EMPIRE

The Germanic peoples who had invaded the Roman Empire over the course of the fifth century had, by the early 500s, established a set of kingdoms in what had been the Western Empire. The Vandals ruled North Africa in a kingdom centered on Carthage, a kingdom whose pirates threatened the Mediterranean for nearly eighty years. The Visigoths ruled Spain in a kingdom that preserved many elements of Roman culture. In Italy, the Roman general Odavacar had established his own kingdom in 476 before being murdered by the Ostrogoth king Theodoric, who established a kingdom for his people in Italy, which he ruled from 493 to his death in 526. Vandal, Visigoth, and Ostrogoth peoples all had cultures that had been heavily influenced over decades or even centuries of contact with Rome. Most of them were Christians, but, crucially, they were not Catholic Christians, who believed in the doctrine of the Trinity, that God is one God but three distinct persons of the Father, the Son (Jesus Christ), and the Holy Spirit. They were rather Arians, who believed that Jesus was lesser than God the Father (see Chapter Six). Most of their subjects, however, were Catholics.

The Catholic Church increasingly looked to the bishop of Rome for leadership. Over the fifth century, the bishop of Rome had gradually come to take on an increasing level of prestige among other bishops. Rome had been the city where Peter, whom tradition regarded as the chief of Christ’s disciples, had ended his life as a martyr. Moreover, even though the power of the Western Roman Empire crumbled over the course of the 400s, the city of Rome itself remained prestigious. As such, by the fourth and fifth centuries, the bishops of Rome were often given the title of papa, Latin for “father,” a term that we translate into pope. Gradually, the popes came to be seen as having a role of leadership within the wider Church, although they did not have the monarchial authority that later popes would claim.

In the region of Gaul, the Franks were a Germanic people who had fought as mercenaries in the later Roman Empire and then, with the disintegration of the Western Empire, had established their own kingdom. One key reason for the Frankish kingdom’s success was that its kings received their legitimacy from the Church. In the same way that the Christian Church had endorsed the Roman emperors since Constantine and, in return, these emperors supported the Church, the Frankish kings took up a similar relation with the Christian religion. King Clovis (r. 481–509) united the Franks into a kingdom and, in 496, converted to Christianity. More importantly, he converted to the Catholic Christianity of his subjects in post-Roman Gaul. This would put the Franks in sharp contrast with the Vandals, Visigoths, and Ostrogoths, all of whom were Arians.

In none of these kingdoms, Visigothic, Ostrogothic, Frankish, or Vandal, did the Germanic peoples who ruled them seek to destroy Roman society—far from it. Rather, they sought homelands and to live as the elites of the Roman Empire had done before them. Theodoric, the king of the Ostrogoths (r. 493–526), had told his people to “obey Roman customs… [and] clothe [them] selves in the morals of the toga.”[1] Indeed, in the generations after the end of the Western Empire in the late 400s, an urban, literate culture continued to flourish in Spain, Italy, and parts of Gaul. The Germanic peoples often took up a place as elites in the society of what had been Roman provinces, living in rural villas with large estates. Local elites shifted their allegiances from the vanished Roman Empire to their new rulers. In many ways, the situation of Western Europe was analogous to that of the successor states of the Han Dynasty such as Northern Wei, in which an invader took up a position as the society’s new warrior aristocracy (see Chapter Four).

But even though the Germanic kings of Western Europe had sought to simply rule in the place of (or along with) their Roman predecessors, many of the features that had characterized Western Europe under the Romans—populous cities; a large, literate population; a complex infrastructure of roads and aqueducts; and the complex bureaucracy of a centralized state—vanished over the course of the sixth century. Cities shrank drastically, and in those regions of Gaul north of the Loire River, they nearly all vanished in a process that we call ruralization. As Europe ruralized and elite values came to reflect warfare rather than literature, schools gradually vanished, leaving the Church as the only real institution providing education. So too did the tax-collecting apparatus of the Roman state gradually wither in the Germanic kingdoms. The Europe of 500 may have looked a lot like the Europe of 400, but the Europe of 600 was one that was poorer, more rural, and less literate.

7.6 BYZANTIUM: THE AGE OF JUSTINIAN

An observer of early sixth-century Italy would have thought that its Ostrogothic kingdom was the best poised to carry forward with a new state that, in spite of its smaller size than the Roman Empire, nevertheless had most of the same features. But the Ostrogothic kingdom would only last a few decades before meeting its violent end. That end came at the hands of the Eastern Roman Empire, the half of the Roman Empire that had continued after the end of the Empire in the West. We usually refer to that empire as the Byzantine Empire or Byzantium.

The inhabitants and rulers of this Empire did not call themselves Byzantines but rather referred to themselves as Romans. Their empire, after all, was a continuation of the Roman state. Modern historians call it the Byzantine Empire in order to distinguish it from the Roman Empire that dominated the Mediterranean world from the first through fifth centuries. The Byzantine Empire or Byzantium is called such by historians because Byzantium had been an earlier name for its capital, Constantinople.

By the beginning of the sixth century, the Byzantine army was the most lethal army to be found outside of China. In the late fifth century, the Byzantine emperors had built up an army capable of dealing with the threat of both Hunnic invaders and the Sassanids, a dynasty of aggressively expansionist kings who had seized control of Persia in the third century. Soon this army would turn against the Ostrogothic kingdom of Italy.

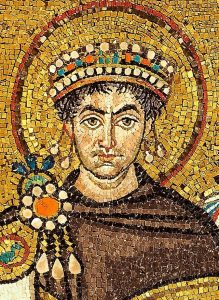

The man who would destroy the Ostrogothic as well as the Vandal kingdom was the emperor Justinian (r. 527–565). Justinian had come not from the ranks of the aristocracy of the Eastern Roman Empire but rather from the army. Even before the death of his uncle, the emperor Justin I (r. 518–527), Justinian was taking part in the rule of the Empire. Upon his accession to the imperial throne, he carried out a set of policies designed to emphasize his own greatness and that of his empire. He did so in the domain of art and architecture, sponsoring the construction of numerous buildings both sacred and secular. The centerpiece of his building campaign was the church called Hagia Sophia, Greek for “Divine Wisdom.” His architects placed this church in the central position of the city of Constantinople, adjacent to the imperial palace. This placement was meant to demonstrate the close relationship between the Byzantine state and the Church that legitimated that state. The Hagia Sophia would be the principal church of the Eastern Empire for the next thousand years, and it would go on to inspire countless imitations.

This Church was the largest building in Europe. Its domed roof was one hundred and sixty feet in height, and supported by four arches one hundred and twenty feet high, it seemed to float in the diffuse light that came in through its windows. The interior of the church was burnished with gold, gems, and marble, so that observers in the church were said to have claimed that they could not tell if they were on earth or in heaven. Even a work as magnificent as the Hagia Sophia, though, showed a changed world: it was produced with mortar rather than concrete, the technology for the making of which had already been forgotten.

While Justinian’s building showed his authority and right to rule which came from his close relations with the Church, his efforts as a lawmaker showed the secular side of his authority. Under his direction, the jurist Tribonian took the previous 900 years’ worth of Roman Law and systematized it into a text known as the Body of Civil Law or the Justinian Code. This law code, based on the already-sophisticated system of Roman Law, would go on to serve as the foundation of European law and thus of much of the world’s law as well.

Although the Justinian Code was based on the previous nine centuries of gathered law, Roman Law itself had changed over the course of the fifth century with the Christianization of the Empire. By the time of Justinian’s law code, Jews had lost civil rights to the extent that the law forbade them from testifying in court against Christians. Jews would further lose civil rights in those Germanic kingdoms whose law was influenced by Roman Law as well. The reason for this lack of Jewish civil rights was that many Christians blamed Jews for the execution of Jesus and believed that Jews refused out of stubbornness to believe that Jesus had been the Messiah. A Christian Empire was thus one that was often extremely unfriendly to Jews.

As Byzantine emperor (and thus Roman emperor), Justinian would have regarded his rule as universal, so he sought to re-establish the authority of the Empire in Western Europe. The emperor had other reasons as well for seeking to re-establish imperial power in the West. Both Vandal Carthage and Ostrogoth Italy were ruled by peoples who were Arians, regarded as heretics by a Catholic emperor like Justinian.

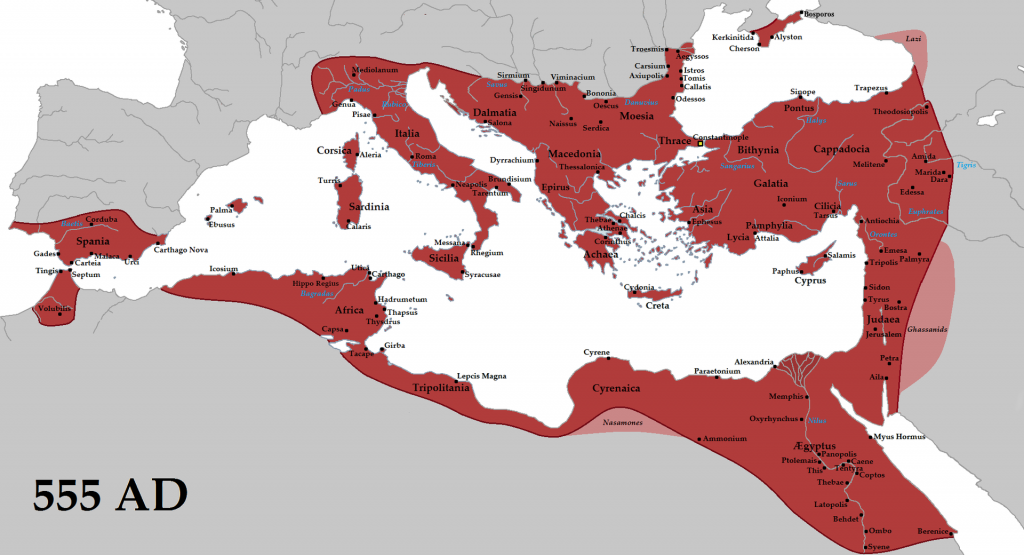

During a dispute over the throne in the Vandal kingdom, the reigning monarch was overthrown and fled to the Eastern Empire for help and protection. This event gave Justinian his chance. In 533, he sent his commander Belisarius to the west, and in less than a year, this able and capable general had defeated the Vandals, destroyed their kingdom, and brought North Africa back into the Roman Empire. Justinian then turned his sights on a greater prize: Italy, home of the city of Rome itself, which, although no longer under the Empire’s sway, still held a place of honor and prestige.

In 535, the Roman general Belisarius crossed into Italy to return it to the Roman Empire. Unfortunately for the peninsula’s inhabitants, the Ostrogothic kingdom put up a more robust fight than had the Vandals in North Africa. It took the Byzantine army nearly two decades to destroy the Ostrogothic kingdom and return Italy to the rule of the Roman Empire. In that time, however, Italy itself was irrevocably damaged. The city of Rome had suffered through numerous sieges and sacks. By the time it was fully in the hands of Justinian’s troops, the fountains that had provided drinking water for a city of millions were choked with rubble, the aqueducts that had supplied them smashed. The great architecture of the city lay in ruins, and the population had shrunk drastically from what it had been even in the days of Theodoric (r. 493–526).

Justinian’s reconquest of Italy would prove to be short-lived. Less than a decade after restoring Italy to Roman rule, the Lombards, another Germanic people, invaded Italy. Although the city of Rome itself and the southern part of the peninsula remained under the rule of the Byzantine Empire, much of northern and central Italy was ruled by either Lombard kings or other petty nobles.

But war was only one catastrophe to trouble Western Europe. For reasons that are poorly understood even today, the long-range trade networks across the Mediterranean Sea gradually shrank over the sixth and seventh centuries. Instead of traveling across the Mediterranean, wine, grain, and pottery were increasingly sold in local markets. Only luxury goods—always a tiny minority of most trade—remained traded over long distances.

Nor was even the heartland of Justinian’s empire safe from external threat. The emperor Heraclius (r. 610–641) came to power in the midst of an invasion of the Empire by the Sassanid Persians, who, under their king Khusrau (see Chapter Eight), threatened the Empire’s very existence, his armies coming within striking range of Constantinople itself. Moreover, Persian armies had seized control of Egypt and the Levant, which they would hold for over a decade. Heraclius thwarted the invasion only by launching a counterattack into the heart of the Persian Empire that resulted, in the end, in a Byzantine victory. No sooner had the Empire repelled one threat than another appeared that would threaten the Empire with consequences far more severe. Under the influence of the Prophet Muhammad, the tribes of the Arabian deserts had been united under first the guidance of the Prophet and then his successors, the caliphs and the religion founded by Muhammad, Islam (see Chapter Eight). Under the vigorous leadership of the first caliphs, Arab Muslim armies invaded both Sassanid Persia and the Byzantine Empire. At the Battle of Yarmouk in 636, although the Byzantines and Arabs were evenly matched, the Byzantine field army was badly beaten. In the aftermath, first Syria and Palestine and then Egypt fell from Christian Byzantine rule to the cultural and political influence of Islam.

The seventh century also saw invasions by various semi-nomadic peoples into the Balkans, the region between the Greek Peloponnese and the Danube River. Among these peoples were the Turkic Bulgars, the Avars (who historians think might have been Turkic), and various peoples known as Slavs. The Avars remained nomads on the plains of Central Europe, but both Bulgars and Slavs settled in Balkan territories that no longer fell under the rule of the Byzantine state. Within a generation, the Empire had lost control of the Balkans as well as Egypt, territory comprising an immense source of wealth in both agriculture and trade. By the end of the seventh century, the Empire was a shadow of its former self.

Indeed, the Byzantine Empire faced many of the social and cultural challenges that Western Europe did, although continuity with the Roman state remained. In many cases, the cities of the Byzantine Empire shrank nearly as drastically as did the cities of Western Europe. Under the threat of invasion, many communities moved to smaller settlements on more easily defended hilltops. The great metropolises of Constantinople and Thessalonica remained centers of urban life and activity, but throughout much of the Empire, life became overwhelmingly rural.

Even more basic elements of a complex society, such as literacy and a cash economy, went into decline, although they did not cease. The Byzantine state issued less money, and indeed, most transactions ceased to be in cash at this time. The economy was demonetized. Even literacy rates shrank. Although churchmen and other elites would often still have an education, the days of the Roman state in which a large literate reading public would buy readily-available literature were gone. As in the west, literacy increasingly became the preserve of the religious.

7.7 PERSPECTIVES: POST-ROMAN EAST AND WEST

In many ways, the post-Roman Germanic kingdoms of Western Europe and the Byzantine Empire shared a similar fate. Both saw a sharp ruralization—that is, a decline in the number of inhabited cities and the size of those cities that were inhabited. Both saw plunges in literacy. And both saw a state that was less competent—even at tax collection. Moreover, the entire Mediterranean Sea and its environs showed a steady decline in high-volume trade, a decline that lasted for nearly two and a half centuries. By around the year 700, almost all trade was local.

But there remained profound differences between Byzantium and the Germanic kingdoms of Western Europe. In the first place, although its reach had shrunk dramatically from the days of Augustus, the imperial state remained. Although the state collected less in taxes and issued less money than in earlier years, even in the period of the empire’s greatest crisis, it continued to mint some coins, and the apparatus of the state continued to function. In Western Europe, by contrast, the Germanic kingdoms gradually lost the ability to collect taxes (except for the Visigoths in Spain). Likewise, they gradually ceased to mint gold coins. In Britain, cities had all but vanished. The island was inhabited by peoples living in small villages, the remnants of Rome’s imperial might standing as silent ruins.

The post-Roman world stands in contrast to post-Han China. Although the imperial state collapsed in China, literacy never declined as drastically as in the Roman Empire. The apparatus of tax collection and other features of a functional state also remained in the Han successor states to an extent that they did not in either Rome or Byzantium.

7.8 THE BRITISH ISLES: EUROPE’S PERIPHERY

In many of the lands that had been part of the Roman Empire, the Germanic peoples who had taken over Western Europe built kingdoms. Although not as sophisticated as the Roman state, they were still recognizable as states. This situation stood in sharp contrast to Britain. To the northwest of Europe, the Roman Army had abandoned the island of Britain in 410. The urban infrastructure brought about by the Roman state began to decay almost immediately, with towns gradually emptying out as people returned to rural lifeways that had existed prior to Rome’s arrival.

At nearly the same time that the Roman Army withdrew from Britain, a group of Germanic peoples known as the Anglo-Saxons were moving into the island from the forests of Central Europe that lay to the east, across the sea. Unlike the Franks, Visigoths, and Ostrogoths, each of whom had kingdoms, the social organization of the Anglo-Saxons was comparatively unsophisticated. They were divided among chiefs and kings who had a few hundred to a few thousand subjects each.

Between about 410 and 600, the Anglo-Saxons gradually settled in and conquered much of southeastern Britain, replacing the Celtic-speaking peoples and their language. The island of Britain was completely rural. All that remained of the state-building of the Romans was the ruins of abandoned cities.

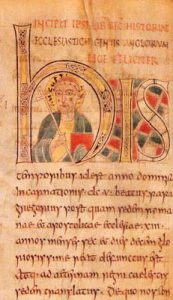

And yet, it would be England (called England because the name is derived from the word Anglo-Saxon) and the island of Ireland to its west that would lead to an increase of schools and literacy across Western Europe. In the fifth century, Christian missionaries traveled to Ireland and converted many of its peoples. In the early 600s, Pope Gregory the Great sent missionaries to the island of Britain. The English peoples adopted Christianity (usually under the initiative of their kings) over the course of the next several decades, which in turn led to the founding of monasteries. These monasteries would usually have attached schools so that those seeking to live as monks could have access to the texts of the Bible, the liturgy, and the writings of other churchmen. English churchmen like Benedict Biscop (c. 628–690) traveled south to Rome and returned to England with cartloads of books. English and Irish monks would often copy these books in their own monasteries.

Indeed, England saw not only the copying of older books but also the composition of original literature, which was rare elsewhere in Western Europe of this time. The English churchman Bede (672–735) composed a history of England’s people. He wrote this history to show how the Anglo-Saxons had adopted Christianity. Within a few decades of the island’s peoples converting to Christianity, English and Irish monks were traveling to Western Europe, either to establish monasteries in lands already Christian or to serve as missionaries to those still-pagan peoples in the forests of Central Europe.

7.9 BYZANTIUM: CRISIS AND RECOVERY

Although the Byzantine Empire was a remnant of the Roman state, by the eighth century, it was much weaker than the Roman Empire under Augustus or even than the Eastern Empire under Justinian. After their conquest of Egypt, the forces of the caliphate had built a navy and used it to sail up and lay siege to Constantinople itself in two sieges lasting from 674 to 678 and from 717 to 718. On land, to the northwest, the Empire faced the threat of the Bulgars, Slavs, and Avars. The Avars, a nomadic people, demanded that the Byzantine state pay them a hefty tribute to avoid raids. At the very moment that the Empire was in greatest need of military strength, it was poorer than it had ever been.

The solution was a reorganization of the military. Instead of having a military that was paid out of a central treasury, the emperors divided the Empire up into regions called themes. Each theme would then equip and pay soldiers, using its agricultural resources to do so. Themes in coastal regions were responsible for the navy. In many ways, this was similar to the way that other states would raise soldiers in the absence of a strong bureaucratic apparatus. One might liken it to what we call feudalism in Zhou China, Heian Japan, and later Medieval Europe.

The greatest crisis faced by the Byzantine Empire in these years of crisis was the so-called Iconoclast Controversy. From the fourth and fifth centuries, Christians living in the Eastern Mediterranean region had used icons to aid in worship. An icon is a highly stylized painting of Christ, the Virgin Mary (his mother), or the saints. Often icons appeared in churches, with the ceiling painted with a picture of Christ or with an emblem of Christ above the entrance of a church.

Other Christians opposed this use of images. In the Old Testament (the term Christians use to refer to the Hebrew Bible), the Ten Commandments forbid the making of “graven images” and using them in worship (Exodus 20:4–5). Certain Christians at the time believed that to make an image even of Jesus Christ and his mother violated that commandment, arguing that to paint such pictures and use them in worship was idolatry—that is, worshiping something other than God. Muslims leveled similar critiques at the Christian use of icons, claiming that Christians had fallen from the correct worship of God into idolatry.

Emperor Leo III (r. 717–41) accepted these arguments; consequently, in his reign, he began to order icons removed (or painted over) first from churches and then from monasteries as well as other places of public display. His successors took further action, ordering the destruction of icons. These acts by Leo led to nearly a century of controversy over whether the use of icons in worship was permissible to Christians. The iconophiles argued that to use a picture of Christ and the saints in worship was in line with the Christian scriptures so long as the worshiper worshiped God with the icon as a guide, while the iconoclasts proclaimed that any use of images in Christian worship was forbidden.

In general, monks and civilian elites were iconophiles, while iconoclasm was popular with the army. In Rome, which was slipping out from under the jurisdiction of the Byzantine emperors, the popes strongly rejected iconoclasm. Some historians have argued that Leo and his successors attacked icon worship for reasons other than religious convictions alone, including the fact that monks who venerated icons had built up their own power base; more importantly, in confiscating the wealth of iconophile monasteries, the emperor would be able to better fund his armed forces.

The iconophile empress Irene, ruling on behalf of her infant son Constantine V (r. 780–797), convoked a new church council to bring an end to the controversy. At the 787 Second Council of Nicaea, the Church decreed that icons could be used in worship. Final resolution of the Iconoclast Controversy, however, would have to wait until 843, when the empress Theodora at last overturned iconoclastic policies for good upon the death of her husband, the emperor Theophilus (r. 829–843). From this point forward, historians usually refer to the Greek-speaking churches of the eastern Mediterranean and those churches following the same patterns of worship as Eastern Orthodox.[2]

Although the iconoclast emperors had made enemies in the Church, they were often effective military commanders, and they managed to stabilize the frontiers with Arabs, Slavs, and Bulgars. Byzantine armies of the eighth century would have some successes against Arabs and Slavs, but Byzantium increasingly lost control of Italy. While a Byzantine exarch, or governor, in Ravenna (in northeastern Italy) would rule the city of Rome, even these Italian territories were gradually lost. Ravenna fell to the Lombards in 751; the duke of Naples ceased to acknowledge the authority of the emperor in Constantinople in the 750s; and the popes in Rome, long the de facto governors of the city, became effectively independent from Byzantium in the 770s. The popes would increasingly look to another power to secure their city: the Franks.

7.10 WESTERN EUROPE: THE RISE OF THE FRANKS

At the west end of the Mediterranean and in northern Europe, the kingdom of the Franks would become the dominant power of the Christian kingdoms. Justinian’s armies had destroyed the Ostrogothic kingdom in Italy in the sixth-century Gothic War. A century and a half later, in 711, Arab Muslim invaders from North Africa conquered the Visigoth kingdom in Spain and established Muslim rule. From that time on, we refer to Muslim-ruled Spain of the early Middle Ages as al-Andalus. The destruction of these two kingdoms left the Franks as the dominant power of Western Europe. They were already the premier power in northern Gaul, but as the seventh century went on, they established themselves in southern Gaul as well, gradually subordinating other Germanic peoples to their rule.

The first dynasty of Frankish kings was known as the Merovingians, so named for Merovech, a possibly legendary ancestor of Clovis, the first Christian king of the Franks. The Franks’ power grew in Western Europe for several reasons. In the first place, the Frankish monarchy had fewer civil wars than did that of the Visigoths. The Frankish kingdom did face the weakness that it was sometimes divided among a king’s sons at his death (since Germanic peoples often looked at a kingdom as the king’s personal property), with warfare resulting within the divided kingdom. Nevertheless, although the kingdom might be split by inheritance and later reunited, there existed in general a strong sense of legitimate dynastic succession. In addition, the Catholic Church provided the Frankish monarchs with a sense of legitimacy as it had since the days of Clovis.

But as the Frankish kingdom expanded, many elements of what had characterized the Roman state continued to wither. One reason for this decline was that the nature of warfare had changed in Western Europe. Soldiers were no longer paid out of a government treasury; instead, they were rewarded with lands whose surplus they would use to outfit themselves with military equipment. The soldiers thus served as a warrior aristocracy. Even those families who had been Roman elites took up a military lifestyle in order to prosper in the new order. In addition, the Frankish kings increasingly made use of a pillage and gift system. In a pillage and gift system, a king or other war leader rewards his loyal soldiers by granting them gifts that came from the plunder of defeated enemies. With armies financed either by pillage and gift or by the wealth of an individual aristocrat’s lands, the Frankish kingdom had little reason for maintaining taxation. Moreover, the kingdom’s great landowners who supported the monarchy had a strong interest in seeing that they were not taxed efficiently; by the 580s, the Frankish government had simply ceased to update the old Roman tax registers.

One role that would gain prominence among the Frankish monarchy was that of the Major Domo, or Mayor of the Palace. The Mayor of the Palace was a noble who would grant out lands and gifts on behalf of the king and who would, in many cases, command the army. Gradually, one family of these Mayors of the Palace would rise to prominence above all other noble families in the Frankish kingdom: the Carolingians.

This dominant family’s more prominent members were named Charles, which in Latin is Carolus, hence the name Carolingians. By the mid-seventh century, the Carolingians had come to hold the position of Mayor of the Palace as a hereditary one. Over the early eighth century, the Carolingian Mayors of the Palace had become the actual rulers of the Frankish realm, while the Merovingian kings had little or no actual power. The earliest significant Carolingian Major Domo to dominate the Carolingian court was Charles Martel (r. 715–741). He was an able and effective military commander who—even though he rewarded his troops with lands taken from the Church—was able to show himself a defender of the Christian religion by defeating a Muslim attack on Gaul from al-Andalus in 732 at the Battle of Tours. In 738, he also defeated the Saxons, who were at this point still largely pagans living in the forests to the northeast of the Frankish kingdom. These victories allowed Martel to present his family as defenders of the Church and of the Christian religion in general.

Martel’s successor, Pepin the Short (r. 741–68), would take the final step towards wresting power away from the Merovingians and making his family the kings of the Franks. He followed in Martel’s footsteps in using the Church to shore up his legitimacy. He wrote to Pope Zachary I (r. 741–752), asking whether one who exercised the power of a king should have that power or if instead the person with the name of king should have that power. Pope Zachary answered that kingship should rest with the person exercising its power—because a king ruled the earth on behalf of God, so a king who was not properly ruling was not doing his God-given duty. Thus the last Merovingian king was deposed by the combined powers of the Carolingian Mayors of the Palace and the popes. This close cooperation between Church and crown would go on to be a defining feature of the Frankish monarchy.

The relationship between the papacy and the Carolingians not only involved the popes legitimating Pepin’s coup d’état but also included the Carolingian monarchs providing military assistance to the popes. Shortly after Zachary’s letter allowing Pepin to seize power, Pepin marched south to Italy to give the pope military assistance against the Lombards. He took control of several cities and their surrounding hinterlands and gave these cities as a gift to the papacy. The popes would thus rule a set of territories in central Italy known as the Papal States from Pepin’s day until the mid-nineteenth century.

The greatest of the Carolingians was the figure we refer to as Charlemagne, whose name means Charles the Great. As king of the Franks, he spent nearly the entirety of his reign leading his army in battle. To the southeast, he destroyed the khanate of the Avars, the nomadic people who had lived by raiding the Byzantine Empire. To the northeast of his realm, he subjugated the Saxons of Central Europe and had them converted to Christianity—a sometimes brutal process. When the Saxons rebelled in 782, he had 4,000 men executed in one day for having returned to their old religion. To the south in Italy, Charlemagne militarily conquered the Lombard kingdom and made himself its king. The only area in which he was less successful was in his invasion of al-Andalus. Although his forces seized control of several cities and fortresses in northeastern Spain (to include places like Barcelona), he was, on the whole, less successful against Spain’s Umayyad emirs. One reason for this lack of success was that, compared to Charlemagne’s other foes, al-Andalus was organized into a sophisticated state, and so better able to resist him.

By the end of the eighth century, Charlemagne ruled nearly all of Western Europe. Indeed, he ruled more of Western Europe than anyone since the Roman emperors of four centuries before. In the winter of 800, a mob expelled Pope Leo III from Rome. Charlemagne took his troops south of the Alps and restored the pope to his position in the Lateran palace, the palace complex to the northeast of Rome where the popes both lived and conducted most of their business.

On Christmas Day in 800, Charlemagne was attending worship at St. Peter’s Church. During that ceremony, the pope placed a crown upon Charlemagne’s head and declared him to be Roman emperor. Historians are not sure whether Charlemagne had planned this coronation or had simply gone up to the pope for a blessing and was surprised by this crown. The question of who had planned this coronation is controversial because the pope’s crowning the emperor could have been interpreted to mean that the crown was the pope’s to confer.

Indeed, it was around this time that a document known as the Donation of Constantine appeared in Western Europe. This document was a forgery—to this day, scholars do not know who forged it—that claimed to have been written by the Roman emperor Constantine (see Chapter Six). According to this forged document, the emperor Constantine had been cured of leprosy by Pope Sylvester I and, in thanks, had given the popes authority over the Western Empire. Although false, this document would go on to provide the popes with a claim to rule not just central Italy but Western Europe as a whole.

Charlemagne’s coronation by the pope marked the culmination of the creation of a new society built on the wreck of the Western Roman Empire. This new society would be Christian and based on close cooperation of Church and State—although each would regard the others’ sphere of influence as separate.

7.11 GLOBAL CONTEXT

Although Charlemagne possessed one of the most powerful armies in Europe, the Mediterranean, and the Middle East, his empire was hardly a state compared to Tang China, the Abbasid Caliphate, or the Byzantine Empire. Compared to the armies of the Byzantine emperors, the Abbasid Caliphs, and above all, the Tang emperors, Charlemagne’s army was merely a very large war band, financed not by a state with a working system of taxation and treasury but rather by the plunder of defeated enemies. Although he issued decrees known as capitularies through the agencies of Church and State, the realm had little in the way of either bureaucracy or infrastructure, save for the decaying network of the Roman Empire’s roads. Indeed, although Charlemagne had sought to have a canal dug between the Rhine and Danube Rivers, this project failed—a fitting illustration of the gap between the ambitions of Charlemagne and the reality.

7.11.1 The Carolingian Renaissance

In those territories that had been part of the Western Roman Empire, most of the people had spoken Latin, and Latin was the language of literature. By the time of the Carolingians, Latin was starting to change into the languages that would eventually become French, Spanish, Italian, and Portuguese, languages that we call Romance because they are descended from Latin, the language of the Romans. The Bible, the liturgy, and writings on saints and theology, however, were still in Latin. Even those who could read and write Latin, though, were less skillful than their predecessors. There were fewer books of Roman literature available in Western Europe; the copying of books gradually dwindled with literacy.

The Carolingians were known not only for their conquests and attempted revival of the Roman Empire but also for their efforts to improve the state of learning in the Carolingian Empire, particularly with respect to the Bible, theology, and literature of Ancient Rome. They also sought to increase the number of schools and books in the realm. Historians refer to this effort as the Carolingian Renaissance. Historians call it the Carolingian Renaissance in order to distinguish it from the later Italian Renaissance, an effort by northern Italian artists and writers of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries to restore teaching and learning of the literature of Ancient Greece and Rome.

Charlemagne and his successors sponsored an increase in learning by the Church to promote moral reform. Charlemagne, like his predecessors and successors, considered himself a defender and protector of the Christian religion. As such, he wanted to make sure that the Church was promoting moral reform. This would need to start with clergy, and these clergy would need to be able to adequately read the Bible and other texts.

Charlemagne’s efforts would be centered on schools and centers of book production, what scholars of medieval Europe call scriptoria (singular scriptorium). There were already high-quality schools attached to monasteries in his empire, including many established by English and Irish monks. The main school of his empire was the school in his palace at Aachen. His palace itself was based on Roman and Byzantine architecture, as a demonstration that he possessed the same sort of legitimacy as the Roman emperors. He invited some of the best scholars of Western Europe to his court—including Alcuin of York (735–804), a monk from England—in order both to supervise his own court school and to direct the Church of the Frankish Empire to improve learning.

This improvement of learning included the establishment of new cathedral schools, schools attached to a cathedral church (i.e., a church where the bishop of a diocese—the basic geographic division of the Church—has his seat). These schools trained not only men and women from the church but also the children of Frankish aristocrats, and in some cases women as well as men. As a result, an increasing number of Frankish nobles would be literate or at least would sponsor efforts by schools to further train people.

Likewise, under the guidance of Charlemagne and the Frankish church, scriptoria throughout his empire launched a massive effort to copy new books. Many of these books were religious in character, although Carolingian monks (and nuns) would also copy books from Ancient Rome that had been written by pagans. Many of these ancient books, like the poetry of Virgil (see Chapter Six), would serve as the basis of the curriculum of Western Europe’s schools as they had since the Roman Empire. A Christian of the eighth century would believe that even works by pagans would afford their readers education and, thus, self-improvement.

7.11.2 The Macedonian Renaissance

The Byzantine Empire had been that half of the Roman Empire where the language of life and culture was not Latin but Greek. At around the same time as the Carolingians’ efforts, the Byzantine Church and State cooperated to revive the study of ancient literature and improve learning. The Byzantine Empire had suffered from a collapse of literacy, which, while not as severe as Western Europe’s, had still resulted in a much less literate population. As such, a similar renaissance of learning was needed in the Greek-speaking Eastern Mediterranean. We call this effort the Macedonian Renaissance because it reached its fullest expression under a dynasty of Byzantine emperors that we call the Macedonian Dynasty (867–1056).

The efforts of the Macedonian Dynasty, however, had begun earlier. The efforts to improve the availability of books and to increase learning began during the Iconoclast Controversy as both Iconophiles and Iconoclasts had sought to back up their positions by quoting from the Bible and the Church Fathers. Emperor Theophilus (r. 829–842), one of the last Iconoclast emperors, asked Leo the Mathematician to found a school in the emperor’s palace in Constantinople. Like Charlemagne’s palace at Aachen, this school would serve as the foundation for a revived learning among elites, only this learning was in Greek rather than Latin.

Following the final triumph of the Iconophiles, these efforts continued with Photius, patriarch of Constantinople from 858 to 867 and 877 to 886. He sponsored monastic schools in the Byzantine Empire and the copying of books in Ancient Greek, particularly Plato’s philosophy and the epic poetry of Homer.

7.11.3 Comparisons with the Abbasids

We should also note the global context of both the Carolingian and the Macedonian Renaissance. Carolingian and Macedonian Emperors were not alone in seeking to increase the availability of Ancient Greek and Roman texts. The Abbasid Caliphs under al-Mamun (r. 813–883) and his successors also sponsored the work of the House of Wisdom, whose scholars translated the philosophy of the Ancient Greeks into Arabic. Like the Christians of the Carolingian and Byzantine Empires, the Muslims of the Caliphate believed that one could learn from pagan writers even if they had not believed in the one Creator God.

7.12 DAILY LIFE IN WESTERN EUROPE AND THE BYZANTINE EMPIRES

In both Western Europe and Byzantium, the vast majority of the population were farmers. In Western Europe, some of these were dependent farmers—farmers who lived on the lands of aristocrats and gave much of their surplus to their landlords. But in many villages, the majority of farmers might live on their own land and even enjoy a form of self-government. Although some slavery existed—especially in zones of conflict like the Mediterranean—the workers on the estates of the Frankish aristocracy or those free and independent farmers enjoyed greater freedom than had their Roman counterparts. But life was precarious. Crop yields were low, at ratios of around 3:1 (producing three times as much as was planted). The average Carolingian farmer frequently did not get adequate calories.

So too did most of the population of the Byzantine Empire live in small villages, living at a subsistence level and selling what rare surplus they had. Byzantium, like its Western European counterpart, was fundamentally rural.

The nobles of Western Europe were generally part of a warrior aristocracy. These aristocrats often outfitted and equipped themselves based on the wealth of their lands. Their values were those of service to their king and loyalty and bravery in battle. Nobles would often not live on their lands but follow the royal court, which would itself travel from place to place rather than having a fixed location. Battle may have been frequent, but until Charlemagne, the scale of battle was often small, with armies numbering a few hundred at most.

Along with its warrior aristocracy, gender roles in the Frankish kingdom—like those of the Roman Empire that came before it—reflected a patriarchal society. The Christian religion generally taught that wives were to submit to their husbands, and the men who wrote much of the religious texts often thought of women in terms of weakness and temptation to sexual sin. “You,” an early Christian writer had exclaimed of women, “are the devil’s gateway…you are the first deserter of the divine law…you destroyed so easily God’s image, man…”[3] The warlike values of the aristocracy meant that aristocratic women were relegated to a supporting role, to the management of the household. Both Roman and Germanic law placed women in subordination to their fathers and then, when married, to their husbands.

That said, women did enjoy certain rights. Although legally inferior to men in Roman Law (practiced in the Byzantine Empire and often among those peoples who were subjects of the Germanic aristocracies), a wife maintained the right to any property she brought into a marriage. Women often played a strong economic role in peasant life, and as with their aristocratic counterparts, peasant women often managed the household even if men performed tasks such as plowing and the like. And the Church gave women a fair degree of autonomy in certain circumstances. We often read of women choosing to become nuns, to take vows of celibacy, against the desires of their families for them to marry. These women, if they framed their choices in terms of Christian devotion, could often count on institutional support for their life choices. Although monasticism was usually limited to noblewomen, women who became nuns often had access to an education. Certain noblewomen who became abbesses could even become powerful political actors in their own right, as did Gertrude of Nivelles (c. 621–659), abbess of the monastery of Nivelles in what is today Belgium.

7.13 CAROLINGIAN COLLAPSE

Charlemagne’s efforts to create a unified empire did not long outlast Charlemagne himself. His son, Louis the Pious (r. 814–840), succeeded him as emperor. Unlike Charlemagne, who had had only one son to survive into adulthood, Louis had three. In addition, his eldest, Lothar, had already rebelled against him in the 830s. When Louis died, Lothar went to war with Louis’s other two sons, Charles the Bald and Louis the German. This civil war proved to be inconclusive, and at the 843 Treaty of Verdun, the Carolingian Empire was divided among the brothers. Charles the Bald took the lands in the west of the Empire, which would go on to be known first as West Francia and then, eventually, France. To the east, the largely German-speaking region of Saxony and Bavaria went to Louis the German. Lothar, although he had received the title of emperor, received only northern Italy and the land between Charles’s and Louis’s kingdoms.

This division of a kingdom was not unusual for the Franks—but it meant that there would be no restoration of a unified Empire in the West, although both the king of Francia and the rulers of Central Europe would each claim to be Charlemagne’s successors.

Western Europe faced worse problems than civil war between the descendants of Charlemagne. In the centuries following the rise of the post-Roman Germanic kingdoms, Western Europe had suffered comparatively few invasions. The ninth and tenth centuries, by contrast, would be an “age of invasions.”

In the north of Europe, in the region known as Scandinavia, a people called the Norse had lived for centuries before. These were Germanic peoples, but one whose culture was not assimilated to the post-Roman world of the Carolingian west. They were still pagan and had a culture that, like that of other Germanic peoples, was quite warlike. Their population had increased; additionally, Norse kings tended to exile defeated enemies. These Norsemen would often take up raiding other peoples, and when they did so, they were known as Vikings.

One factor that allowed Norse raids on Western Europe was an improvement in their construction of ships. Their ships were long and flexible and had a shallow enough draft that they did not need harbors. They could land on any beach, and they could sail up rivers for hundreds of miles. This meant that Norse Vikings could strike almost anywhere, often with very little warning.

Even more significant for the Norse attacks was that Western Europe in the ninth and tenth centuries was made up of weak states. The three successor kingdoms to Charlemagne’s empire were often split by civil war. Although King Charles the Bald (r. 843–877) enjoyed some successes against the Vikings, his realm was subject to frequent raids. England’s small kingdoms were particularly vulnerable. From 793, England suffered numerous Viking raids, and these raids increased in size and scope over the ninth century. Ireland, with its chiefs and petty kings, also lacked the organization necessary to resist sustained incursions.

The result was that Viking raids on the British Isles increased in scope and intensity over the ninth century. Eventually, the Norse captured land there for permanent settlement.

To the south and west, al-Andalus suffered fewer Norse attacks than did the rest of Europe. A sophisticated, organized state with a regular army and a network of fortresses, it was able to effectively deal with raiders. The Spanish emir Abd-al Rahman II defeated a Viking raid and sent the Moroccan ambassador the severed heads of 200 Vikings to show how successful he had been in defending against them.

To the east, the Norse sailed along the rivers that stretched through the forests and steppes of the area that today makes up Russia and Ukraine. The Slavic peoples living there had a comparatively weak social organization, so in many instances, they fell under Norse domination. The Norsemen Rurik and Oleg were said to have established themselves as rulers of Slavic peoples as well as the princedoms of Novgorod and Kyiv, respectively, in the ninth century. These kingdoms of Slavic subjects and Norse rulers became known as the Rus.

Further to the south, the Norse would often move their ships over land between rivers until finally reaching the Black Sea and thus Constantinople and Byzantium. Although the Norse were occasionally successful in raiding Constantinople, the powerful and organized Byzantine state was generally able to defend itself.

Norse invaders were not the only threat faced by Western Europe. As the emirs of Muslim North Africa gradually broke away from the centralized rule of the Abbasid Caliphate (see Chapter Eight), these emirs turned to legitimate themselves by raid and plunder. This aggression was often directed at southern Francia and Italy. The Aghlabid emirs not only seized control of Sicily but also sacked the city of Rome itself in 846. North African raiders would often seize territory on the coasts of Southern Europe and raid European shipping to control trade and commerce. In addition, the emirs of these North African states would use the plunder from their attacks to reward followers—another example of the pillage and gift system.

Central Europe also faced attacks, these from the Magyars, a steppe people. The Magyars had been forced out of Southeastern Europe by another steppe people, the Pechenegs. From 899, the Magyars migrated into Central Europe, threatening the integrity of East Francia. As was the case with other steppe peoples, their raids on horseback targeted people in small unfortified communities, avoiding larger settlements. The Magyars eventually settled in the plains of Eastern Europe, establishing the state of Hungary. Although they made Hungary their primary location, they nevertheless continued to raid East Francia through the first part of the tenth century.

7.13.1 An Age of Invasions in Perspective

Norse, Magyar, and Muslim attacks on Europe wrought incredible damage. Thousands died, and tens of thousands more were captured and sold into slavery in the great slave markets of North Africa and the Kyivan Rus. These raids furthered the breakdown of public order in Western Europe, but they also brought long-term economic benefits. Norse and Muslim pirates traded as much as they raided. Indeed, even the plunder of churches and selling of the gold and silver helped create new trade networks in both the North Sea and Mediterranean. These new trade networks, especially where the Norse had established settlements in places like Ireland, gradually brought about an increase in economic activity.

All told, we should remember this “age of invasions” in terms both of its human cost and of the economic growth it brought about.

7.13.2 New States in Response to Invasions

In response to the invasions that Europe faced, newer, stronger states came into being in the British Isles and in Central Europe. In England, Norse invasions had destroyed all but one of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms. The only remaining kingdom was Wessex. Its king, Alfred the Great (r. 871–899), was able to stop Norse incursions by raising an army and navy financed by a kingdom-wide tax. This tax, known as the geld, was also used to finance the construction of a network of fortresses along the frontier of those parts of England still controlled by the Norse. This new system of tax collection would mean that England, a small island on the periphery, would eventually have the most sophisticated bureaucracy in Western Europe.

Likewise, in Central Europe, the kings of East Francia gradually built a kingdom capable of dealing with Magyar invaders. Henry the Fowler (r. 919–936) took control of East Francia after the end of the Carolingian Dynasty. He was succeeded by Otto the Great (r. 936–973), whose creation of a state was partially the result of luck: his territory contained large silver mines that allowed him to finance an army. This army was able to decisively defeat the Magyar raiders. This allowed East Francian kings to expand their power to the east, subjugating the Slavic peoples living in the forests of Eastern Europe.

7.14 THE TENTH-CENTURY CHURCH

As a result of endemic chaos in Western Europe, the Church suffered as well. The moral and intellectual quality of bishops and abbots declined sharply, as church establishments fell under the domination of warlords. These warlords would often appoint members of their families or personal allies to positions of leadership in the Church, appointments based not on competence or dedication to duty but rather on ties of loyalty. This was even the case in Rome, where families of Roman nobles fought over the papacy. Between 872 and 965, twenty-four popes were assassinated in office.

7.15 BYZANTINE APOGEE: THE MACEDONIAN EMPERORS

For Byzantium, however, the ninth and tenth centuries represented a time of recovery and expansion. This period included the height of the Macedonian Renaissance, which brought a growth of learning among both clergy and lay elites. This took place against a backdrop of military success by the emperors of the Macedonian Dynasty (867–1056). The first emperor of this dynasty, Basil I (r. 867–886), a soldier and servant of the emperor, had come from a peasant background. He seized control of the Empire when he murdered the reigning emperor and took the position for himself.

Basil was an effective emperor. To the east, as the Abbasid Caliphate broke down, he inflicted several defeats on the Arab emirs on the border, pushing the frontiers of the Empire further east. Although unsuccessful in fighting to maintain control of Sicily, he re-established Byzantine control over most of southern Italy.

It was under the Macedonian emperors that the Eastern Orthodox culture of the Byzantines spread north beyond the borders of the Empire. In 864, the Bulgar khan, whose predecessors had been building a state of their own, converted to Christianity and was baptized. This conversion allowed the Bulgar state to be legitimated by the Church in the same manner as the Byzantine Empire and the kingdoms of Western Europe.

In the ninth century, Cyril and Methodius, missionaries from the city of Thessalonica, preached Orthodox Christianity to the Slavic peoples of Eastern Europe. They also devised the alphabet that we call Cyrillic in order to write the Bible and liturgy in the language of Eastern Europe, Slavonic. By bringing Orthodox Christianity to the Slavic peoples, the Byzantines brought them into the culture of the Byzantines.

Subsequent emperors maintained this record of successes. John Tzimisces (r. 969–976) established Byzantine control over most of Syria. Basil II (r. 976–1025) achieved further successes, crushing and annexing the neighboring Bulgar state and subordinating the Armenian kingdoms to the Byzantine emperor. By the end of his reign, the Byzantine territory encompassed about a fourth of what had been the Roman Empire at its height. Basil II had further diplomatic triumphs. He allied with the princes of the Kyivan Rus, a state that had grown up in Eastern Europe along the rivers between the Baltic Sea and the Black Sea. The Rus population was largely Slavic, with rulers who were ethnically Norse; it was already a hybrid culture. An alliance with the Byzantine Empire also brought Greek elements into the cultural mix. In 988, Kyivan Grand Prince Vladimir (r. 980–1015) was baptized into the Christian religion and became a close ally of Basil II, sealing the alliance by marrying Basil’s sister, Anna. The elite culture of the Rus would come to reflect both Greek, Slavic, Norse, and Turkic elements. Allying with these people had brought Basil II to the height of the Byzantine state’s power.

Despite its successes during the reign of the Macedonian emperors, the Byzantine state faced weaknesses. The theme system gradually broke down. Increasingly, soldiers came not from the themes but from the ranks of professional mercenaries, to include those made up of Norsemen. The soldiers of the themes received less training and served mainly as a militia that would back up the core of a professional army, known as the Tagmata. Whether the smaller tagmata would be up to the task of defending an empire the size of Byzantium would remain to be seen.

7.16 CONCLUSION AND GLOBAL PERSPECTIVES

In many ways, the period between 500 and 1000 was as transitional for Western Europe and Byzantium as it was for East Asia and the Middle East and North Africa. Just as the Han State had fragmented politically in the third century and given rise to smaller states ruled by warrior aristocracies, so too had Rome fragmented into an eastern half and a series of Germanic kingdoms, themselves ruled by warrior aristocracies. Just as Mahayana Buddhism had arrived in post-Han China, so too had Christianity become the dominant faith of the Roman Empire and its successors.

And yet, these similarities are superficial. All of China’s successor states maintained a continuity of bureaucracy and literacy to an extent that Western Europe did not. Moreover, although Mahayana Buddhism would become a key element of East Asian culture, it would never come to enjoy the monopoly of power that Christianity enjoyed in Western Europe and Byzantium and that Islam enjoyed in Spain, the Middle East, and North Africa. The less exclusivist nature of Mahayana Buddhism would mean that it would always be one set of practices among many.

And the greatest difference is that China eventually saw a return to a unified empire under the Sui and then Tang Dynasties. In spite of Charlemagne’s efforts to create a new Empire in the west, the story of Western Europe would be one of competing states rather than an empire claiming universal authority.

7.17 WORKS CONSULTED AND FURTHER READING

Backman, Clifford R. The Worlds of Medieval Europe. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.

Fouracre, Paul, ed. The New Cambridge Medieval History, Volume 1: c.500–c.700. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

McKitterick, Rosamond, ed. The New Cambridge Medieval History, Volume 2: c.700–c.900. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995.

Ostrogorsky, George. History of the Byzantine State. Translated by Joan Hussey. Revised ed. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1969.

Rautman, Marcus. Daily Life in the Byzantine Empire. London: Greenwood Press, 2006.

Reuter, Timothy, ed. The New Cambridge Medieval History, Volume 3: c.900–c.1024. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

Wickham, Chris. The Inheritance of Rome: Illuminating the Dark Ages, 400–1000. The Penguin History of Europe 2. New York: Penguin, 2009.

- Cassiodorus, Variae, trans. Thomas Hodgkin, in The Medieval Record: Sources of History, ed. Alfred J. Andrea (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1997), 58 ↵

- Modern historians use this label for convenience. At the time, both Churches in the Greek-speaking eastern Mediterranean and those following the pope would have said that they were part of the Catholic Church (the word catholic comes from a Greek word for “universal”). The churches in the eastern Mediterranean and Eastern Europe were coming to differ enough in terms of practice, worship, and thought that we can refer to them as distinct from the Catholic Church of Western Europe. ↵

- Tertullian, On the Apparel of Women, 1:1. ↵