1.1 Restoring the Union

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe Lincoln’s plan to restore the Union at the end of the Civil War

- Discuss the tenets of Radical Republicanism

- Analyze the success or failure of the Thirteenth Amendment

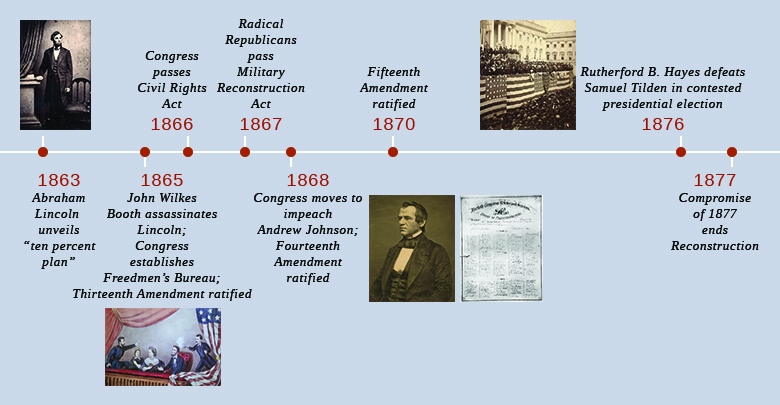

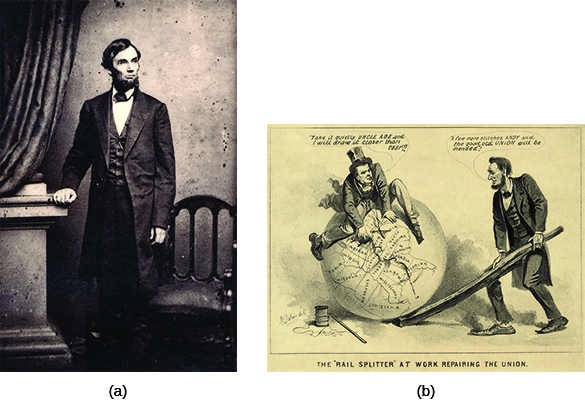

The end of the Civil War saw the beginning of the Reconstruction era, when former rebel southern states were integrated back into the Union. President Lincoln moved quickly to achieve the war’s ultimate goal: reunification of the country. He proposed a generous and non-punitive plan to return the former Confederate states speedily to the United States, but some Republicans in Congress protested, considering the president’s plan too lenient to the rebel states that had torn the country apart. The greatest flaw of Lincoln’s plan, according to this view, was that it appeared to forgive traitors instead of guaranteeing civil rights to formerly enslaved people. President Lincoln oversaw the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment abolishing slavery, but he did not live to see its ratification.

The President’s Plan

From the outset of the rebellion in 1861, Lincoln’s overriding goal had been to bring the southern states quickly back into the fold in order to restore the Union (Figure 1.3). In early December 1863, the president began the process of reunification by unveiling a three-part proposal known as the ten percent plan that outlined how the states would return. The ten percent plan gave a general pardon to all Southerners except high-ranking Confederate government and military leaders, required 10 percent of the 1860 voting population in the former rebel states to take a binding oath of future allegiance to the United States and the emancipation of the enslaved, and declared that once those voters took those oaths, the restored Confederate states would draft new state constitutions.

Lincoln hoped that the leniency of the plan—90 percent of the 1860 voters did not have to swear allegiance to the Union or to emancipation—would bring about a quick and long-anticipated resolution and make emancipation more acceptable everywhere. This approach appealed to some in the moderate wing of the Republican Party, which wanted to put the nation on a speedy course toward reconciliation. However, the proposal instantly drew fire from a larger faction of Republicans in Congress who did not want to deal moderately with the South. These members of Congress, known as Radical Republicans, wanted to remake the South and punish the rebels. Radical Republicans insisted on harsh terms for the defeated Confederacy and protection for formerly enslaved people, going far beyond what the president proposed.

In February 1864, two of the Radical Republicans, Ohio senator Benjamin Wade and Maryland representative Henry Winter Davis, answered Lincoln with a proposal of their own. Among other stipulations, the Wade-Davis Bill called for a majority of voters and government officials in Confederate states to take an oath, called the Ironclad Oath, swearing that they had never supported the Confederacy or made war against the United States. Those who could not or would not take the oath would be unable to take part in the future political life of the South. Congress assented to the Wade-Davis Bill, and it went to Lincoln for his signature. The president refused to sign, using the pocket veto (that is, taking no action) to kill the bill. Lincoln understood that no southern state would have met the criteria of the Wade-Davis Bill, and its passage would simply have delayed the reconstruction of the South.

The Thirteenth Amendment

Despite the 1863 Emancipation Proclamation, the legal status of enslaved people and the institution of slavery remained unresolved. The news of the Proclamation wouldn’t even reach the entire country for another two and a half years. To deal with the remaining uncertainties, the Republican Party made the abolition of slavery a top priority by including the issue in its 1864 party platform. The platform read: “That as slavery was the cause, and now constitutes the strength of this Rebellion, and as it must be, always and everywhere, hostile to the principles of Republican Government, justice and the National safety demand its utter and complete extirpation from the soil of the Republic; and that, while we uphold and maintain the acts and proclamations by which the Government, in its own defense, has aimed a deathblow at this gigantic evil, we are in favor, furthermore, of such an amendment to the Constitution, to be made by the people in conformity with its provisions, as shall terminate and forever prohibit the existence of Slavery within the limits of the jurisdiction of the United States.” The platform left no doubt about the intention to abolish slavery.

The president, along with the Radical Republicans, made good on this campaign promise in 1864 and 1865. A proposed constitutional amendment passed the Senate in April 1864, and the House of Representatives concurred in January 1865. The amendment then made its way to the states, where it swiftly gained the necessary support, including in the South. In December 1865, the Thirteenth Amendment was officially ratified and added to the Constitution. The first amendment added to the Constitution since 1804, it overturned a centuries-old practice by permanently abolishing slavery.

Click and Explore

Explore a comprehensive collection of documents, images, and ephemera related to Abraham Lincoln on the Library of Congress website.

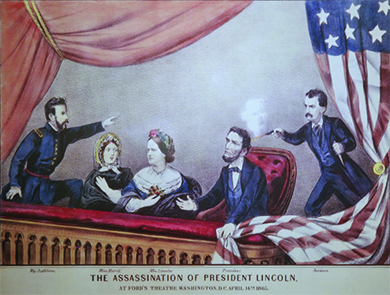

President Lincoln never saw the final ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment. On April 14, 1865, the Confederate supporter and well-known actor John Wilkes Booth shot Lincoln while he was attending a play, Our American Cousin, at Ford’s Theater in Washington. The president died the next day (Figure 1.4). Booth had steadfastly defended the Confederacy and White supremacy, and his act was part of a larger conspiracy to eliminate the heads of the Union government and keep the Confederate fight going. One of Booth’s associates stabbed and wounded Secretary of State William Seward the night of the assassination. Another associate abandoned the planned assassination of Vice President Andrew Johnson at the last moment. Although Booth initially escaped capture, Union troops shot and killed him on April 26, 1865, in a Virginia barn. Eight other conspirators were convicted by a military tribunal for participating in the conspiracy, and four were hanged. Lincoln’s death earned him immediate martyrdom, and hysteria spread throughout the North. To many Northerners, the assassination suggested an even greater conspiracy than what was revealed, masterminded by the unrepentant leaders of the defeated Confederacy. Militant Republicans would use and exploit this fear relentlessly in the ensuing months.

Despite the Emancipation Proclamation and the ratification progress of the Thirteenth Amendment, slavery endured for some time. The news of the war’s end and the freedom of the enslaved people traveled slowly, and in some cases was likely deliberately withheld. When Major General Gordan Granger arrived in Galveston, Texas, to assert control, he brought with him a stunning announcement:

“The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired labor.”

The date, June 19, 1865, would become the most popular annual celebration of the end of slavery, known as Juneteenth. The order was met with resistance and outright opposition. Some slaveholders chose to keep the news from enslaved people. And when people who learned about their emancipation decided to take advantage of their freedom, many were captured or killed. While the pathway to full freedom remained difficult, and discrimination and segregation would remain in place, newly freed Texans began organizing celebrations (also referred to as Jubilee Day and Emancipation Day) as early as 1866. Austin held its first Juneteenth celebration in 1867.

Andrew Johnson and the Battle Over Reconstruction

Lincoln’s assassination elevated Vice President Andrew Johnson, a Democrat, to the presidency. Johnson had come from very humble origins. Born into extreme poverty in North Carolina and having never attended school, Johnson was the picture of a self-made man. His wife had taught him how to read, and he had worked as a tailor, a trade he had been apprenticed to as a child. In Tennessee, where he had moved as a young man, he gradually rose up the political ladder, earning a reputation for being a skillful stump speaker and a staunch defender of poor Southerners. He was elected to serve in the House of Representatives in the 1840s, became governor of Tennessee the following decade, and then was elected a U.S. senator just a few years before the country descended into war. When Tennessee seceded, Johnson remained loyal to the Union and stayed in the Senate. As Union troops marched on his home state of North Carolina, Lincoln appointed him governor of the then-occupied state of Tennessee, where he served until being nominated by the Republicans to run for vice president on a Lincoln ticket. The nomination of Johnson, a Democrat and a slaveholding Southerner, was a pragmatic decision made by concerned Republicans. It was important for them to show that the party supported all loyal men, regardless of their origin or political persuasion. Johnson appeared an ideal choice, because his nomination would bring with it the support of both pro-southern elements and the War Democrats who rejected the conciliatory stance of the Copperheads, the northern Democrats who opposed the Civil War.

Unexpectedly elevated to the presidency in 1865, this formerly impoverished tailor’s apprentice and unwavering antagonist of the wealthy southern planter class now found himself tasked with administering the restoration of a destroyed South. Lincoln’s position as president had been that the secession of the southern states was never legal; that is, they had not succeeded in leaving the Union, therefore they still had certain rights to self-government as states. In keeping with Lincoln’s plan, Johnson desired to quickly reincorporate the South back into the Union on lenient terms and heal the wounds of the nation. This position angered many in his own party. The northern Radical Republican plan for Reconstruction looked to overturn southern society and specifically aimed at ending the plantation system. President Johnson quickly disappointed Radical Republicans when he rejected their idea that the federal government could provide voting rights for formerly enslaved people. The initial disagreements between the president and the Radical Republicans over how best to deal with the defeated South set the stage for further conflict.

In fact, President Johnson’s Proclamation of Amnesty and Reconstruction in May 1865 provided sweeping “amnesty and pardon” to rebellious Southerners. It returned to them their property, with the notable exception of the people they had enslaved, and it asked only that they affirm their support for the Constitution of the United States. Those Southerners exempted from this amnesty included the Confederate political leadership, high-ranking military officers, and persons with taxable property worth more than $20,000. The inclusion of this last category was specifically designed to make it clear to the southern planter class that they had a unique responsibility for the outbreak of hostilities. But it also satisfied Johnson’s desire to exact vengeance on a class of people he had fought politically for much of his life. For this class of wealthy Southerners to regain their rights, they would have to swallow their pride and request a personal pardon from Johnson himself.

For the southern states, the requirements for readmission to the Union were also fairly straightforward. States were required to hold individual state conventions where they would repeal the ordinances of secession and ratify the Thirteenth Amendment. By the end of 1865, a number of former Confederate leaders were in the Union capital looking to claim their seats in Congress. Among them was Alexander Stephens, the vice president of the Confederacy, who had spent several months in a Boston jail after the war. Despite the outcries of Republicans in Congress, by early 1866 Johnson announced that all former Confederate states had satisfied the necessary requirements. According to him, nothing more needed to be done; the Union had been restored.

Understandably, Radical Republicans in Congress did not agree with Johnson’s position. They, and their northern constituents, greatly resented his lenient treatment of the former Confederate states, and especially the return of former Confederate leaders like Alexander Stephens to Congress. They refused to acknowledge the southern state governments he allowed. As a result, they would not permit senators and representatives from the former Confederate states to take their places in Congress.

Instead, the Radical Republicans created a joint committee of representatives and senators to oversee Reconstruction. In the 1866 congressional elections, they gained control of the House, and in the ensuing years, they pushed for the dismantling of the old southern order and the complete reconstruction of the South. This effort put them squarely at odds with President Johnson, who remained unwilling to compromise with Congress, setting the stage for a series of clashes.