The global timeline of immigration at the Library of Congress offers a summary of immigration policies and the groups affected by it, as well as a compelling overview of different ethnic groups’ immigration stories. Browse through to see how different ethnic groups made their way in the United States.

4.2 The African American “Great Migration” and New European Immigration

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Identify the factors that prompted African American and European immigration to American cities in the late nineteenth century

- Explain the discrimination and anti-immigration legislation that immigrants faced in the late nineteenth century

New cities were populated with diverse waves of new arrivals, who came to the cities to seek work in the businesses and factories there. While a small percentage of these newcomers were White Americans seeking jobs, most were made up of two groups that had not previously been factors in the urbanization movement: African Americans fleeing the racism of the farms and former plantations in the South, and southern and eastern European immigrants. These new immigrants supplanted the previous waves of northern and western European immigrants, who had tended to move west to purchase land. Unlike their predecessors, the newer immigrants lacked the funds to strike out to the western lands and instead remained in the urban centers where they arrived, seeking any work that would keep them alive.

The African American “Great Migration”

Between the end of the Civil War and the beginning of the Great Depression, nearly two million African Americans fled the rural South to seek new opportunities elsewhere. While some moved west, the vast majority of this Great Migration, as the large exodus of African Americans leaving the South in the early twentieth century was called, traveled to the Northeast and Upper Midwest. The following cities were the primary destinations for these African Americans: New York, Chicago, Philadelphia, St. Louis, Detroit, Pittsburgh, Cleveland, and Indianapolis. These eight cities accounted for over two-thirds of the total population of the African American migration.

A combination of both “push” and “pull” factors played a role in this movement. Despite the end of the Civil War and the passage of the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments to the U.S. Constitution (ending slavery, ensuring equal protection under the law, and protecting the right to vote, respectively), African Americans were still subjected to intense racial hatred. The rise of the Ku Klux Klan in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War led to increased death threats, violence, and a wave of lynchings. Even after the formal dismantling of the Klan in the late 1870s, racially motivated violence continued. According to researchers at the Tuskegee Institute, there were thirty-five hundred racially motivated lynchings and other murders committed in the South between 1865 and 1900. For African Americans fleeing this culture of violence, northern and midwestern cities offered an opportunity to escape the dangers of the South.

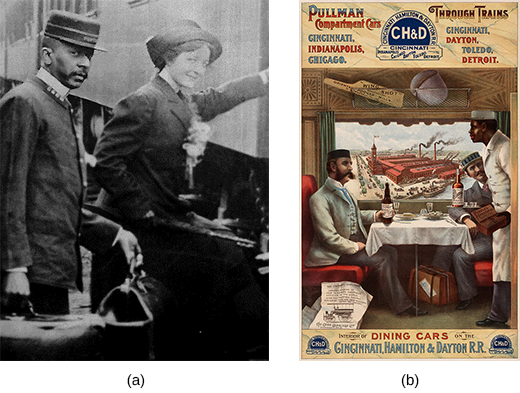

In addition to this “push” out of the South, African Americans were also “pulled” to the cities by factors that attracted them, including job opportunities, where they could earn a wage rather than be tied to a landlord, and the chance to vote (for men, at least), supposedly free from the threat of violence. Although many lacked the funds to move themselves north, factory owners and other businesses that sought cheap labor assisted the migration. Often, the men moved first, then sent for their families once they were ensconced in their new city life. Racism and a lack of formal education relegated these African American workers to many of the lower-paying unskilled or semi-skilled occupations. More than 80 percent of African American men worked menial jobs in steel mills, mines, construction, and meat packing. In the railroad industry, they were often employed as porters or servants (Figure 4.8). In other businesses, they worked as janitors, waiters, or cooks. African American women, who faced discrimination due to both their race and gender, found a few job opportunities in the garment industry or laundries but were more often employed as maids and domestic servants. Regardless of the status of their jobs, however, African Americans earned higher wages in the North than they did for the same occupations in the South, and typically found housing to be more available.

However, such economic gains were offset by the higher cost of living in the North, especially in terms of rent, food costs, and other essentials. As a result, African Americans often found themselves living in overcrowded, unsanitary conditions, much like the tenement slums in which European immigrants lived in the cities. For newly arrived African Americans, even those who sought out the cities for the opportunities they provided, life in these urban centers was exceedingly difficult. They quickly learned that racial discrimination did not end at the Mason-Dixon Line, but continued to flourish in the North as well as the South. European immigrants, also seeking a better life in the cities of the United States, resented the arrival of the African Americans, whom they feared would compete for the same jobs or offer to work at lower wages. Landlords frequently discriminated against them; their rapid influx into the cities created severe housing shortages and even more overcrowded tenements. Homeowners in traditionally White neighborhoods later entered into covenants in which they agreed not to sell to African American buyers; they also often fled neighborhoods into which African Americans had gained successful entry. In addition, some bankers practiced mortgage discrimination, later known as “redlining,” in order to deny home loans to qualified buyers. Such pervasive discrimination led to a concentration of African Americans in some of the worst slum areas of most major metropolitan cities, a problem that remained ongoing throughout most of the twentieth century.

So why move to the North, given that the economic challenges they faced were similar to those that African Americans encountered in the South? The answer lies in noneconomic gains. Greater educational opportunities and more expansive personal freedoms mattered greatly to the African Americans who made the trek northward during the Great Migration. State legislatures and local school districts allocated more funds for the education of both Black and White people in the North, and also enforced compulsory school attendance laws more rigorously. Similarly, unlike the South where a simple gesture (or lack of a deferential one) could result in physical harm to the African American who committed it, life in larger, crowded northern urban centers permitted a degree of anonymity—and with it, personal freedom—that enabled African Americans to move, work, and speak without deferring to every White person with whom they crossed paths. Psychologically, these gains more than offset the continued economic challenges that Black migrants faced.

The Changing Nature of European Immigration

Immigrants also shifted the demographics of the rapidly growing cities. Although immigration had always been a force of change in the United States, it took on a new character in the late nineteenth century. Beginning in the 1880s, the arrival of immigrants from mostly southern and eastern European countries rapidly increased while the flow from northern and western Europe remained relatively constant (Table 4.1).

| Region Country | 1870 | 1880 | 1890 | 1900 | 1910 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Northern and Western Europe | 4,845,679 | 5,499,889 | 7,288,917 | 7,204,649 | 7,306,325 |

| Germany | 1,690,533 | 1,966,742 | 2,784,894 | 2,663,418 | 2,311,237 |

| Ireland | 1,855,827 | 1,854,571 | 1,871,509 | 1,615,459 | 1,352,251 |

| England | 550,924 | 662,676 | 908,141 | 840,513 | 877,719 |

| Sweden | 97,332 | 194,337 | 478,041 | 582,014 | 665,207 |

| Austria | 30,508 | 38,663 | 123,271 | 275,907 | 626,341 |

| Norway | 114,246 | 181,729 | 322,665 | 336,388 | 403,877 |

| Scotland | 140,835 | 170,136 | 242,231 | 233,524 | 261,076 |

| Southern and Eastern Europe | 93,824 | 248,620 | 728,851 | 1,674,648 | 4,500,932 |

| Italy | 17,157 | 44,230 | 182,580 | 484,027 | 1,343,125 |

| Russia | 4,644 | 35,722 | 182,644 | 423,726 | 1,184,412 |

| Poland | 14,436 | 48,557 | 147,440 | 383,407 | 937,884 |

| Hungary | 3,737 | 11,526 | 62,435 | 145,714 | 495,609 |

| Czechoslovakia | 40,289 | 85,361 | 118,106 | 156,891 | 219,214 |

The previous waves of immigrants from northern and western Europe, particularly Germany, Great Britain, and the Nordic countries, were relatively well off, arriving in the country with some funds and often moving to the newly settled western territories. In contrast, the newer immigrants from southern and eastern European countries, including Italy, Greece, and several Slavic countries like Russia, came over due to “push” and “pull” factors similar to those that influenced the African Americans arriving from the South. Many were “pushed” from their countries by a series of ongoing famines; by the need to escape religious, political, or racial persecution; or by the desire to avoid compulsory military service. They were also “pulled” by the promise of consistent wage-earning work.

Whatever the reason, these immigrants arrived without the education and finances of the earlier waves of immigrants, and settled more readily in the port towns where they arrived, rather than setting out to seek their fortunes in the West. By 1890, over 80 percent of the population of New York would be either foreign-born or children of foreign-born parentage. Other cities saw huge spikes in foreign populations as well, though not to the same degree, due in large part to Ellis Island in New York City being the primary port of entry for most European immigrants arriving in the United States.

The number of immigrants peaked between 1900 and 1910, when over nine million people arrived in the United States. To assist in the processing and management of this massive wave of immigrants, the Bureau of Immigration in New York City, which had become the official port of entry, opened Ellis Island in 1892. Today, nearly half of all Americans have ancestors who, at some point in time, entered the country through the portal at Ellis Island. Doctors or nurses inspected the immigrants upon arrival, looking for any signs of infectious diseases (Figure 4.9). Most immigrants were admitted to the country with only a cursory glance at any other paperwork. Roughly 2 percent of the arriving immigrants were denied entry due to a medical condition or criminal history. The rest would enter the country by way of the streets of New York, many unable to speak English and totally reliant on finding those who spoke their native tongue.

Seeking comfort in a strange land, as well as a common language, many immigrants sought out relatives, friends, former neighbors, townspeople, and countrymen who had already settled in American cities. This led to a rise in ethnic enclaves within the larger city. Little Italy, Chinatown, and many other communities developed in which immigrant groups could find everything to remind them of home, from local language newspapers to ethnic food stores. While these enclaves provided a sense of community to their members, they added to the problems of urban congestion, particularly in the poorest slums where immigrants could afford housing.

Click and Explore

This Library of Congress exhibit on the history of Jewish immigration to the United States illustrates the ongoing challenge immigrants felt between the ties to their old land and a love for America.

The demographic shift at the turn of the century was later confirmed by the Dillingham Commission, created by Congress in 1907 to report on the nature of immigration in America; the commission reinforced this ethnic identification of immigrants and their simultaneous discrimination. The report put it simply: These newer immigrants looked and acted differently. They had darker skin tones, spoke languages with which most Americans were unfamiliar, and practiced unfamiliar religions, specifically Judaism and Catholicism. Even the foods they sought out at butchers and grocery stores set immigrants apart. Because of these easily identifiable differences, new immigrants became easy targets for hatred and discrimination. If jobs were hard to find, or if housing was overcrowded, it became easy to blame the immigrants. Like African Americans, immigrants in cities were blamed for the problems of the day.

Growing numbers of Americans resented the waves of new immigrants, resulting in a backlash. The Reverend Josiah Strong fueled the hatred and discrimination in his bestselling book Our Country: Its Possible Future and Its Present Crisis, published in 1885. In a revised edition that reflected the 1890 census records, he clearly identified undesirable immigrants—those from southern and eastern European countries—as a key threat to the moral fiber of the country, and urged all good Americans to face the challenge. Several thousand Americans answered his call by forming the American Protective Association, the chief political activist group to promote legislation curbing immigration into the United States. The group successfully lobbied Congress to adopt both a literacy test for most immigrants, which eventually passed in 1917, and the Chinese Exclusion Act (discussed in a previous chapter). The group’s political lobbying also laid the groundwork for the subsequent Emergency Quota Act of 1921 and the Immigration Act of 1924, as well as the National Origins Act.