3 Ballet

Learning Objectives

- Explain the function of court dance and the development of ballet.

- Summarize the development of ballet from its professionalization through romantic, classical, avant-garde, neoclassical, and contemporary ballet.

- Associate major ballet milestones with the works and choreographers responsible.

Nothing resembles a dream more than a ballet, and it is this which explains the singular pleasure that one receives from these apparently frivolous representations. One enjoys, while awake, the phenomenon that nocturnal fantasy traces on the canvas of sleep; an entire world of chimeras moves before you.

—Theophile Gautier, French poet

What Is Ballet?

Ballet is the epitome of classical dance in Western cultures. Classical dance forms are structured, and stylized techniques developed and evolved throughout centuries requiring rigorous formal training. Ballet originated with the nobility in the Renaissance courts of Europe. The dance form was closely associated with appropriate behavior and etiquette. Eventually, ballet became a professional vocation as it became a popular form of entertainment for the new middle class to enjoy. Ballet spread throughout the world as dance masters refined their craft and handed their methods down from generation to generation. Over 500 years, it has developed and changed. Dancers and choreographers worldwide have contributed new vocabulary and styles, yet ballet’s essence remains the same.

Ballet Characteristics: Codified Technique

Ballet is a codified dance form ordered systematically and has set movements associated with specific terminology. Ballet is a rigorous art and requires extensive training to perform the technique correctly. The first ballet creators’ principles have survived intact, but different regional and artistic styles have emerged over the centuries. Ballet classes follow a standard structure for progression and are comprised of two sections.

The first part of ballet class typically begins with a warm-up at the barre. The barre is a stationary handrail that dancers hold while working on balance, allowing them to focus on placement, alignment, and coordination. The second half of the ballet class is performed in the center without a barre. Dancers use the entire room to increase their spatial awareness and perform elevated and dynamic movements.

Alignment and Turnout

Ballet emphasizes the lengthening of the spine and the use of turnout, an outward rotation of the legs in the hip socket. This serves both to create an aesthetically pleasing line and increase mobility.

Foot Articulation

Ballet demands a strong articulated foot to perform demanding movements and create an elongated line.

Pointe shoes, a ballet staple, add to the illusion of weightlessness and flight. They are constructed with a hard, flat box to enable dance on the tips of the toes; it is a technique called en pointe that requires years of training and dedication to develop the needed strength in the feet, ankles, calves and legs.

Elevated Movement

Traditionally, ballet favors a light quality, called ballon, with elevated movements. Dancers seem to overcome gravity effortlessly and achieve great height in their leaps and jumps.

Pantomime and Storytelling

Ballet can tell a story without words through a language of gestures called pantomime. Some movements are easily understood or have simple body language, but more abstract concepts are given specific gestures of their own to convey meaning. The facial expressions, the musical phrasing, and dynamics all play a role in communicating the story. Pantomime developed in ballet’s Romantic period and was further incorporated during the classical era.

Watch This

The Royal Ballet dancers demonstrate and decode ballet pantomime for Swan Lake. David Pickering addresses the audience in the basics of pantomime, and audience members mimic the movement. In the second part of the clip, principal dancers Marianele Nunez and Thiago Soares reenact act 2 as David Pickering narrates the pantomime.

Court Dance: Italy and France

In medieval Italy, an early pantomime version featured a single performer portraying all the story characters through gestures and dance. A narrator previewed the story to come, and musicians accompanied the pantomime. Pantomimes were quite popular, but they were sometimes over-the-top in their efforts to be comedic, often resulting in lewd and graphic reenactments. Dance was a part of everyday life. Peasants danced at street fairs, and guild members danced at festivals, but it was in the royal courts that ballet had its genesis.

European Renaissance: Ballet de Cour

Catherine dé Medici

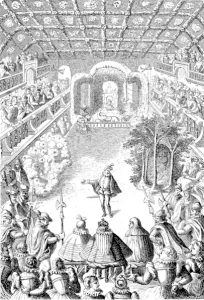

Catherine dé Medici, a wealthy noblewoman of Florence, Italy, married the heir to the French throne, King Henri II. In 1581, she went to Paris for a royal wedding accompanied by Balthazar de Beaujoyeulx, a dance teacher and choreographer. Catherine dé Medici commissioned Beaujoyeulx to create Ballet Comique de la Reine in celebration of the wedding, and it became widely recognized as the first court ballet. The ballet de cour featured independent acts of dancing, music, and poetry unified by overarching themes from Greco-Roman mythology. The ballet included references to court characters and intrigues. After the Ballet Comique de la Reine production, a booklet was published with libretto telling the ballet story. It became the model for ballets produced in other European courts, making France the recognized leader in ballet.

King Louis XIV

During King Louis XIV’s reign, France was a mighty nation. King Louis XIV kept nobility close at hand by moving his court and government to the Palace of Versailles, where he could maintain his power. At court, it was necessary to excel in fencing, dance, and etiquette. Nobility vied for an elevated position in court, as one’s abilities in the finer arts reflected success in politics.

King Louis XIV was a great patron of the arts and vigorously trained in ballet. He performed in several ballet productions. His most memorable role was Apollo, gaining the title the “Sun King” from Le Ballet de la Nuit, which translates to “The Ballet of the Night.”

Louis XIV’s love of dance inspired him to charter the Académie Royal de Musique et Danse, headed by his old dance teacher Pierre Beauchamps and thirteen of the finest dance masters from his court. In this way, the king assured that “la danse classique,” that is to say, “ballet,” would survive and develop. The danse d’ecole provided rigorous training to transition from amateur performance dancers to seasoned professionals. This also opened the door for non-nobility to pursue ballet professionally. For the first time, women were also allowed to train in ballet. Women were only allowed to participate in court social dances until this point. Male performers took on all the roles in court ballets, wearing masks to dance the roles of women.

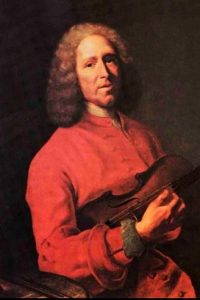

Transitioning from the ballet de cour, dances of the Renaissance ballroom grew into the ballet a entrée, a series of independent episodes linked by a common theme. Early productions of the academy featured the opera-ballet, a hybrid art form of music and dance. Jean-Philippe Rameau served as both composer and choreographer for many early opera-ballets.

At this time, there was a differentiation of characters that dancers assumed. These roles were generally categorized as:

danse noble: regal presentation suitable for roles of royalty

demi-charactere: lively, everyday people; “the girl next door”

comique: exaggerated, caricatured characters

Some significant developments aided in the progression of ballet as an art form at the Académie Royale de Musique et Danse. Pierre Beauchamps significantly contributed to ballet by developing the five basic positions of the feet used in ballet technique. He also laid the foundation for a notation system to record dances. Raoul Auger Feuillet refined the notation and published it in 1700; then, in 1706, John Weaver translated it into English, making it globally accessible.

Watch This

In this split-screen, Feuillet’s dance notation is shown on the left side while dancers perform the Baroque dances on the right side.

The Académie Royale de Musique et Danse was the place to train classical dancers. Dancers and dance masters alike traveled to the great centers of Europe, bringing French ballet to the continent. Today’s Paris Opera Ballet is the direct descendant of the Académie Royal de Musique et Danse.

Watch This

This TED-Ed animated video clip summarizes the origins of ballet:

Dance in the Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment was a philosophical movement that emphasized freedom of expression and the eradication of religious authority. These ideas caused criticism among philosophers who believed art forms should speak to meaningful human expression rather than ornamental art forms.

Jean-Georges Noverre (1727-1810)

Ballet master and choreographer Jean-Georges Noverre challenged ballet traditions and made ballets more expressive. In his famous writings, Letters on Dancing and Ballet, Noverre rejected dance traditions at the Paris Opera Ballet and helped transform ballet into a medium for storytelling. The masks that dancers traditionally wore were stripped away to show dramatic facial expressions and convey meaning within ballets. Pantomime helped tell the story of the ballet. In addition, plots became logically developed with unifying themes, integrating theatrical elements. From Noverre’s concepts, ballet d’action emerged.

Carlo Blasis (1797-1878)

Carlo Blasis was particularly influential in shaping the vocabulary and structure of ballet techniques. He invented the “attitude” position commonly used in ballet from the inspiration of Giambologna’s sculpture of Mercury. He published two major treatises on the execution of ballet, the most notable being “An Elementary Treatise Upon the Theory and Practice of the Art of Dancing.” Blasis taught primarily at LaScala in Milan, where he was responsible for educating many Romantic-era teachers and dancers.

Costume Changes

During the Renaissance, men and women wore elaborate clothing. Women wore laced-up corsets around the torso and panniers (a series of side hoops) fastened around the waist to extend the width of the skirts. Men wore breeches and heeled shoes. The upper body was bound by bulky clothing and primarily emphasized footwork. By the 18th century, there were changes in costuming. Two dancers helped revolutionize costumes.

Marie Sallé (1707-1756)

Marie Sallé was a famous dancer at the Paris Opera, celebrated for her dramatic expression. Her natural approach to pantomime storytelling influenced Noverre. She traded the elaborate clothing that was fashionable at the time to match the subject of the choreography. In her self-choreographed ballet Pygmalion, she wore a less restrictive costume, wearing a simple draped Grecian-style dress and soft slippers. This allowed for less restricted movement and expression.

Marie Camargo (1710-1770)

Marie Camargo, a contemporary of Sallé, exemplified virtuosity and flamboyance in her dancing. She shortened her skirt to just above the ankles to make her impressive fancy footwork visible. She also removed the heels from her shoes, creating flat-soled slippers. This allowed her to execute jumps and leaps that were previously considered male steps.

Check Your Understanding

Romantic Ballet

From France and the royal academy, dance masters brought ballet to the other courts of Europe. These professional teachers and choreographers went to London, Vienna, Milan, and Copenhagen, where the monarchs supported ballet. During the 18th century, the French Revolution ended the French monarchy, and Europe saw political and social changes that profoundly affected ballet. By the 19th century, the Industrial Revolution resulted in middle-class people working in factories. Art shifted from glorifying the nobility to emphasizing the ordinary person.

The Romantic era of ballet reflected this pivotal time. Ballets had now become ballet d’action, ballets that tell a story. The Romantic era was a time of fantasy, etherealism, supernaturalism, and exoticism. Artistic themes included man vs. nature, good vs. evil, and society vs. the supernatural. The dancers appeared as humans and mythical creatures like sylphs, wilis, shades, and naiads. Women were the stars of the ballets, and men took on supporting roles. Choreography now included pointework, pantomime, and the illusion of floating. Romantic ballets most often appeared as two acts. The first act would be set in the real world, and dancers would portray humans. In contrast, the second act was set in a spiritual realm and often would include a tragic end.

Theater Special Effects

The opera houses featured prosceniums, a stage with a frame or arch. The shift of performance venues had a significant effect on ballet in the following ways:

In ballrooms, geometric floor patterns were appreciated by audiences who sat above. The audience’s perspective changed to a frontal view with the introduction of the proscenium stage, and the body became the composition’s focus.

Turned-out legs were emphasized, allowing dancers to travel side-to-side while still facing the audience. This required dancers to have greater skill and technique.

The proscenium stage separated the audience and performers, transitioning ballet from a social function to theatrical entertainment.

Curtains allowed for changes in scenery.

The flickering of the gas lights in the theaters gave a supernatural look to the dancing on the stage.

Theaters also enabled rigging to carry the dancers into the air, giving the illusion of flying.

The stagecraft of the time lent itself to creating the scenes that choreographer Filippo Taglioni would use in his ballets.

La Sylphide

In 1824, ballet master Filippo Taglioni (1777-1871) choreographed La Sylphide. His daughter Marie portrayed the sylphide, an ethereal, spirit-like character. Marie Taglioni (1804-1884) wore a white romantic tutu with a bell-shaped skirt that reached below her knees, creating the effect of flight and weightlessness. Taglioni also removed the heels from her slippers and rose to the tips of her toes as she danced to give her movement a floating and ethereal quality. Taglioni is recognized as one of the first dancers to perform en pointe.

La Sylphide features a corps de ballet, a group of dancers working in unison to create dance patterns. Because the corps de ballet is dressed in white romantic tutus (as is the norm with sylphs, fairies, wilis, and other creatures that populate the worlds of Romantic ballet), La Sylphide is known as a ballet blanc.

Watch This

Watch this video of the Royal Scottish Ballet that describes and shows excerpts from La Sylphide:

Auguste Bournonville (1805-1879)

Auguste Bournonville, a French-trained dancer, served as a choreographer and director in the Royal Danish Ballet. Four years after the original La Sylphide production, Bournonville re-choreographed the ballet. Bournonville’s dances featured speed, elevation, and beats where the legs “flutter” in the air. He also expanded the lexicon of male dancing by adding ballon for men and stylized movements for women that portrayed them as sweet and charming. Bournonville created many dances for the Danish ballet, and the company has preserved his choreography through the centuries.

Watch This

The Bournonville variation from Napoli demonstrates movements of elevation:

Giselle

Giselle is a ballet masterwork that is still performed worldwide. It is inspired by the literary works of Heine and Hugo that referenced the supernatural wilis. Giselle was choreographed by Jean Coralli and Jules Perrot and composed by Adolphe Adam. It is almost a template for the traditional Romantic ballets. Act 1 is set in a village, and act 2 is in a graveyard, an otherworldly place populated by the ghosts of young girls who died before their wedding day—wilis. Giselle falls in love with a young man, Albrecht, who pretends to be a local but is really a nobleman. Distraught by his deception, she dies from grief. When Albrecht visits her grave, the wilis conspire to dance him to death. Giselle, now a wili herself, intervenes to save him.

Coppélia

Not all Romantic-era ballets were tragic and supernatural. Arthur St. Léon created the great comedic ballet Coppélia: “The Girl with the Enamel Eyes.” The ballet is based on a tale by E. T. A. Hoffman. It tells the story of a village boy, Franz, enamored by the girl Coppélia. Unbeknownst to him, she is an automaton. His jealous girlfriend Swanilda discovers the deception created by the doll’s creator, and when the old toymaker tries to animate his doll with magic, she takes the doll’s place and pretends to come to life. The characters’ antics were great hits with audiences, and the ballet remains popular today.

Classical Ballet: Imperial Russia

About the time King Louis XIV was sponsoring the creation of ballet in his court, Peter the Great became tsar of Russia (1682-1725). He embraced science and Western social ideas in an effort to bring “the enlightenment” to Russia. Peter built the imperial city of St. Petersburg and established his court there. His successor, Empress Anna, retained Jean-Baptiste Lande in 1738 to establish a ballet school at the military academy she had established. This school became the home of the Maryinsky Ballet. The Bolshoi Ballet was a rival school and company later established in Moscow.

Following Lande’s lengthy directorship in St. Petersburg, many of Europe’s most important ballet masters and choreographers took a turn at the helm in creating dance in Russia, including Jules Perrot, Filippo Taglioni, and Arthur St. Léon.

Marius Petipa (1818-1910)

Marius Petipa was the most influential choreographer of this era, known as “the father of classical ballet.” A dancer from a family of French ballet dancers, he moved to St. Petersburg as a minor choreographer. He rose to great importance in Russian ballet as the director and choreographer of the Maryinsky Ballet for nearly sixty years (1847–1903). He created over sixty ballets in his career, restaging a number of the great Romantic-era ballets (much of the existing choreography of ballets like Giselle and Coppélia are the work of Marius Petipa’s restaging.) Petipa also created new original ballets, beginning with The Pharaoh’s Daughter, a five-act ballet complete with an underwater scene and livestock onstage.

Characteristics of Classical Ballets

Marius Petipa is responsible for the defining characteristics of classical ballets. Petipa’s creations told stories using ballet, character dance, and choreographic structures that highlighted the most technical dancers of the company.

Classical Ballet Choreographic Structure

Petipa developed a standard choreographic structure. He used character dances, folk dances that depicted various cultures, to add variety to the performance. Unlike the Romantic ballets that consisted of two acts, classical ballets expanded to three or four acts. Many dances that had nothing to do with moving the plot forward were included in these ballets to make them longer. These extra dance numbers are called divertissements (diversions). Divertissements were often character dances. The end of the ballet usually features the grand pas de deux, a duet for the principal dancers. The grand pas de deux has four sections:

Adagio—The principal dancers perform slow movements together that are fluid and controlled.

Man’s Variation—Males display their technical virtuosity by performing leaps, turns, and jumps.

Woman’s Variation—Females often perform quick footwork and turns.

Coda—The principals dance together to display impressive movements.

Watch This

The Sleeping Beauty grand pas de deux featuring Robert Bolle and Diana Vishneva:

Contextual Connections

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893)

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky composed three great ballets. He was already a recognized and respected composer in Russia when Petipa asked him to compose the ballet score for The Sleeping Beauty. Petipa gave Tchaikovsky specific instructions on the music he required for the ballet. The ballet was lavishly produced and became an enormous success.

Tchaikovsky’s second ballet, The Nutcracker, was choreographed by Petipa’s choreographic assistant, Lev Ivanov (1834-1901). Petipa’s choreographic assistant, Lev Ivanov, worked alongside Petipa in the creation of many ballets. He created entire portions of Petipa ballets and ballets of his own.

The Nutcracker was not admired in Russia at the time—it was seen as frivolous and trivial. It was in America in the middle of the twentieth century that The Nutcracker found popularity as a vehicle for local dancers in communities around the country.

The third well-known ballet Tchaikovsky composed was Swan Lake. Marius Petipa choreographed the first and third acts of the ballet—those set in the environs of Prince Siegfried, town and ballroom, and the world of people. Lev Ivanov choreographed acts 2 and 4, the beautiful scenes set at the lake with the swans.

After the revolution of 1917, the Russian populace embraced ballet. Rather than discarding it as a symbol of the tsars, the working class adopted it as their own, and ballet became a symbol of national pride.

At the end of the 19th century, Russia was at the apex of the ballet world, and this continued well into the 20th century. The Vaganova Choreographic Institute in St. Petersburg employs Russia’s finest teachers to train its dancers. The life of a ballet dancer in Russia brings privileges and opportunities that make acceptance into the school highly desirable.

Check Your Understanding

Ballet Russes: Dance and the Avant-Garde

Sergei Diaghilev (1872-1929)

Sergei Diaghilev, a Russian art lover, organized the Ballet Russes in 1909. He identified ballet as the ideal vehicle to present the Russian arts to the West. Diaghilev’s troupe included some of Russia’s finest dancers and choreographers recruited from the Vaganova Institute and the Maryinsky ballet. He promoted collaborations with avant-garde composers and artists of the time. The tour to Paris extended twenty years as the Ballet Russes performed for Paris, Europe, and the Western world. The Ballet Russes introduced a new and modern form of ballet, revitalizing ballet in the West.

Michel Fokine (1880-1942)

The first choreographer of Ballet Russes was Michel Fokine. Like Jean-Georges Noverre, Fokine developed principles to reform ballet. Fokine focused on ballet’s expressiveness rather than physical prowess. He believed movement should serve a purpose to the theme, and costumes should reflect the dress of the time and setting. Fokine also stripped away pantomime in his ballets, emphasizing movement and self-expression as the catalyst for storytelling. His one-act ballet Les Sylphides was reminiscent of the earlier ballet La Sylphide in its use of the ethereal sylph. But Fokine’s ballet had no plot. A single man, a poet, dances among a group of sylphides in a ballet that evokes a dreamlike mood.

Watch This

Excerpt from Les Sylphides (c 1928). This black-and-white clip is some of the only footage of the company that exists. Diaghilev did not want his ballet company to be filmed because he was afraid of losing income from box-office sales.

Fokine’s The Firebird was based on tales from Russian folklore. His Petrouchka told the story of a trio of puppets at a Russian street fair.

Vaslav Nijinsky (1889–1950)

Vaslav Nijinsky was a principal dancer of the company and is remembered for his astonishing gravity-defying jumps and poignant portrayals. When Fokine left the company, Nijinsky became the principal choreographer. He choreographed the Rite of Spring: Tales from Russia, Afternoon of a Faun, and Jeux. Nijinsky’s dances were controversial because the themes, movement aesthetics, and music were unconventional for the time. The Rite of Spring portrays a pagan ritual and fertility rites that left the audience in uproar on its opening night.

Watch This

Excerpt from the Rite of Spring.

Léonide Massine (1895-1979)

Léonide Massine followed Nijinsky as a choreographer, where he expanded on Fokine’s innovations, focusing on narrative, folk dance, and character portrayals in his ballets. Parade is a one-act ballet about French and American street circuses. Pablo Picasso designed the cubist sets and costumes.

Watch This

Excerpt of Parade. The characters are introduced in three groups as they try to entice an audience into the performance. The giant cubist figures portray business promoters.

Bronislava Nijinska (1891-1972)

Bronislava Nijinska, the fourth Ballet Russes choreographer, was Vaslav’s sister and stands out as one of the few recognized women choreographers. Her ballet Les Noces, set to music by Stravinsky, was noted for its architectural qualities. She created several ballets known for being Riviera chic, portraying the carefree lifestyle of Europe’s idle rich.

Watch This

Excerpt from Le Train Bleu; you can see the costumes designed by Coco Chanel.

George Balanchine (1904-1983)

George Balanchine was the fifth and last choreographer of Diaghilev’s Ballet Russes. He created ten ballets for the company. The Prodigal Son is a retelling of the bible story. Apollo shows the birth of the god Apollo and his tutoring in the arts by the three muses. Those two ballets remain in the repertory of the New York City Ballet.

Watch This

Excerpt from Balanchine’s Apollo performed by Pacific Northwest Ballet:

Watch This

This short clip features pictures and footage with commentary by Lynn Garafola, Nancy Reynolds, and Charles M. Smith:

Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo and Original Ballet Russe

The dancers of Ballet Russe were left at loose ends after the death of Diaghilev. A former Russian colonel, Wassily de Basil, joined with Rene Blum and found the funding to buy Diaghilev’s sets and costumes. He hired George Balanchine as the choreographer for the new company, Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo. Balanchine recruited girls of twelve and fourteen to become the new stars of the company. The trio—Tamara Toumanova, Irina Baronova, and Tatiana Riabouchinska—was dubbed the baby ballerinas.

Watch This

Excerpt from Les Sylphides featuring the baby ballerinas:

In little more than a year, Blum had split from de Basil, and Balanchine was replaced with Léonide Massine as choreographer. Massine created ballets from 1932–1937, including Gaite Parisienne, and Les Presages, the first ballet set to a symphony.

Ultimately Massine split from de Basil. In a court battle, de Basil’s company retained the rights to all of Massine’s work during that time. But Massine held on to the name Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo.

The Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo toured Europe, and when World War II broke out, the company sailed for North America, while De Basil’s company, now named The Original Ballet Russe, headed to Australia. They later also toured the US and South America. Both companies performed for countless new audiences, introducing Russian ballet to the New World. American dancers were hired to fill the ranks of the companies. Among others, five Native American ballerinas were hired to tour with the companies.

The Five Moons

Many American dancers found work with Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo and Original Ballet Russe. Five exceptional Native American dancers who became ballerinas with these companies hailed from Oklahoma. Known as the Five Moons, a reference to their tribes, these women gained fame and success at the highest levels of ballet and were foundational in the development of Oklahoma dance institutions.

Maria Tallchief (Osage Nation, 1925–2013) went on to dance with New York City Ballet. She married George Balanchine and worked with him for many years. Balanchine’s Firebird was a signature role for her.

Marjorie Tallchief (Osage Nation, 1926–2021), Maria’s sister, was known for her great versatility as a dancer. She had a successful dancing career in Europe and the United States, then served as director at Dallas Civic Ballet Academy, Chicago’s City Ballet, and Harid Conservatory in Boca Raton.

Moscelyne Larkin (Peoria/Eastern Shawnee/Russian, 1925–2012) first learned ballet from her dancer mother. She starred at Radio City Music Hall and founded Tulsa Ballet Theatre with her husband.

Yvonne Chouteau (Shawnee Tribe, 1929–2016) joined Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo at the age of 14, where she danced many roles from the Ballet Russe repertory. She served as an artist in residence at the University of Oklahoma and founded Oklahoma City Ballet with her husband.

Rosella Hightower (Choctaw Nation, 1920–2008) danced with these major companies and with American Ballet Theatre, but she later found her work in France, as director of Marseilles Opera Ballet and then Ballet de Nancy. Hightower was the first American director of the Paris Opera Ballet.

Both Ballet Russe companies had disbanded by 1960. Many of the retired dancers went on to found ballet schools and companies throughout the New World and Europe.

Neoclassical Ballet

Neoclassical dance utilizes traditional ballet vocabulary, but pieces are often abstract and have no narrative. Several choreographers were experimenting with the neoclassical style. Balanchine’s work is regarded as neoclassical, embracing both classical and contemporary aesthetics. Balanchine wanted the attention to be on the movement itself, highlighting the relationship between music and dancing by creating movement that mirrored the music. Balanchine also employed freedom of the upper body, moving away from the verticality of the spine for a more expressive movement that drew inspiration from vernacular jazz dance styles that became prominent.

American Ballet in the 20th Century

At the invitation of Lincoln Kirstein, George Balanchine went to New York City when the Ballet Russes ended in 1929. In 1934, they established the first ballet school in the United States, the forerunner of the School of American Ballet. It expanded into a short-lived dance company. In 1948, Balanchine established a small company that ultimately grew to become the New York City Ballet (NYCB). New York City Ballet is the resident company of Lincoln Center in NYC and one of the most recognized ballet companies in the country.

George Balanchine was a prolific choreographer with a long career. Due to his contributions to the development of ballet in the United States, Balanchine is known as “the father of American ballet.” He wanted to express modern 20th-century life and ideas to capture the spirit and athleticism of American dancers. Some of his most famous ballets include Serenade, Jewels, Stars and Stripes, and Concerto Barocco.

Watch This

Excerpt of the Rubies pas de deux from the ballet Jewels.

American Ballet Theatre (ABT)

American Ballet Theatre (ABT), a New York City Ballet contemporary, is also recognized as a premier ballet company. Its mission is to preserve the classical repertoire, commission new works, and provide educational programming.

Its directors have included Lucia Chase and Oliver Smith, Mikail Baryshnikov, and Kevin McKenzie. Hundreds of renowned choreographers have created works with ABT. Antony Tudor created intimate psychological ballets, Agnes de Mille created ballets of Americana, and Jerome Robbins produced ballets across a range of styles.

Watch This

Excerpt from Rodeo by Agnes de Mille. The dancers mimic the bowed legs of cowboys and trot about as if they are astride horses. Aaron Copland composed the music.

Ballet grew in other cities of America as well. San Francisco Ballet was founded by Adolphe Bolm, a Ballet Russes dancer. Chicago and Utah both established ballet companies early on.

Other Notable American Ballet Artists: Mid-20th Century

Jerome Robbins (1918-1998)

Jerome Robbins was an American-born dancer and a significant choreographer in ballet, musical theater, and film. Robbins contributed modern ballets to the repertory of New York City Ballet and American Ballet Theatre. His artistic works are influenced by ordinary people and reflect current times.

Watch This

Short documentary that highlights scenes of Fancy Free with commentary by Daniel Ulbricht and Ella Baff. Fancy Free is set in the 1940s; this ballet is about the escapades of sailors onshore. Fancy Free is the precursor for the musical On the Town.

Robert Joffrey (1930-1988)

In 1953 Robert Joffrey began his company, Joffrey Ballet, as a small touring group traveling in a single van. It is primarily known for its pop-culture ballets, like Astarte, and historical recreations of ballets like Nijinsky’s Rite of Spring, Fokine’s Petrouchka, and Massine’s Parade.

Arthur Mitchell

Arthur Mitchell was the first African American principal dancer to perform with a leading national ballet company, New York City Ballet. In 1969, in response to news of Dr. Martin Luther King’s assassination, Mitchell created a ballet school in his childhood neighborhood. The Dance Theatre of Harlem rose from the ballet school, a classical ballet company composed primarily of African American dancers.

Mitchell wanted to produce ballets that would raise the voices of people of color and create opportunities for them to dance professionally. He used his company as a platform for social justice. In his Creole Giselle, Mitchell reimagined the romantic ballet and set it in Louisiana during the 1840s. According to the Dance Theatre of Harlem’s program notes, “During this time, social status among free blacks was measured by how far removed one’s family was from slavery. Giselle’s character is kept the same; her greatest joy is to dance. Albrecht is now Albert, and the wilis are the ghosts of young girls who adore dancing and die of a broken heart.”

Watch This

This archival material from Creole Giselle includes pictures and dancing clips narrated by the dancers of the original ballet, Theara Ward, Augustus Van Heerden, Lorraine Graves:

Check Your Understanding

Contemporary Ballet: Ballet in the 21st Century

Contemporary ballet is a dance genre that uses classical techniques (French terminology) that choreographers manipulate and blend with other dance forms, such as modern dance.

Alonzo King LINES Ballet

Alonzo King is an American choreographer who initially studied at the ABT. King also danced with notable choreographers Alvin Ailey and Arthur Mitchell before founding his company, LINES Ballet. LINES Ballet is located in California, where King uses Western and Eastern classical dance forms to create contemporary ballets.

BalletX

BalletX was founded in 2005 by Christine Cox and Matthew Neenan and is located in Philadelphia. The mission of BalletX is to expand classical vocabulary through its experimentation to push the boundaries of ballet.

Watch This

Christine Cox and Matthew Neenan discuss the mission of BalletX. The footage shows clips of the company’s performances, pictures, and interviews with the company members:

Complexions Contemporary Ballet

In 1994, Complexions was founded by Dwight Rhoden and Desmond Richardson. The mission of Complexions is to foster diverse and inclusive approaches in the making and presentation of their works to inspire change in the ballet world.

Watch This

Excerpt from WOKE that uses music from Logic to explore themes of humanity in response to the political climate.

Other Notable Contemporary Ballet Artists

Nederlands Dans Theater, founded in 1959, is a Dutch contemporary dance company.

William Forsythe founded the Forsythe Company (2005–2015), integrating ballet with visual arts.

Jiří Kylián blends classical ballet steps with contemporary approaches to create abstract dances.

Amy Hall Garner combines ballet, modern, and theatrical dance genres.

Trey McIntyre founded the Trey McIntyre Project in 2005, combining ballet and contemporary dance with visual arts.

Ballet Hispánico, founded by Tina Ramirez in 1970, blends ballet with Latinx dance to create more opportunities for dancers of color, known as one of America’s Cultural Treasures.

Justin Peck is the resident choreographer for New York City Ballet, creating new works; he earned a Tony Award for his choreography in the revival of Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Carousel.

Inclusivity

From its origins in the elite white-only courts of France and Italy and well into the present day, Western dance forms had a history of exclusionism. In the United States, the first Black ballet dancer who broke the color barrier in 1955 to dance in a major ballet company was Raven Wilkinson. Wilkinson danced and toured with the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo. Racial segregation was at its height during this time, forcing Wilkinson to deny her race when performing at most venues. After facing years of discrimination, Wilkinson eventually left the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo. After facing rejection from several American ballet companies, Wilkinson was hired to dance with the Dutch National Ballet. Wilkinson later became a mentor to Misty Copeland.

Misty Copeland

In 2015, Misty Copeland became the first African American female principal dancer with American Ballet Theatre. Copeland is also the first woman of color to take the lead role of Odette/Odile in Swan Lake. Her road to principal dancer was difficult, as many claimed she had the wrong skin color to dance professionally. Due to the racism faced throughout her life, Misty Copeland uses her platform to bring awareness to the challenges people of color face in the ballet world by advocating for diversity.

Watch This

Misty Copeland’s interview on race in ballet.

Hiplet

Racial barriers have caused choreographers to challenge the traditional Eurocentric forms of ballet. Hiplet, a fusion of ballet movement and hip-hop, was created by Homer Hans Bryant to provide opportunities for dancers of color to connect to ballets and express themselves in a contemporary and culturally relevant way.

Watch This

In this video, Hiplet creator Homer Hans Bryant discusses how he developed this dance style:

Gender Roles

Ballets historically tend to follow stereotyped gender roles that emphasize femininity and masculinity. These conventional standards are reinforced in the movements, roles, costuming, and partnering displayed in ballets. In pas de deuxs in classical ballets, female dancers are paired with male dancers. Female dancers are often portrayed as delicate, complacent, ethereal beings. In contrast, male dancers are presented as dominant and strong; they lift their female partners, enforcing the image of men supporting women.

Mathew Bourne

In 1995, Matthew Bourne took a contemporary approach to classical ballet in his reimagined Swan Lake. Bourne disrupts societal expectations by replacing the female swans with men. In the male-male pas de deux, the dancers lift and support each other, shifting the power dynamics to emphasize equality in the movement.

Watch This

“The New Adventures” excerpt of Bourne’s Swan Lake:

LGBTQIA+ Representation

Ballets have also reinforced heterosexual norms and narratives. Societal ideals of feminine- and masculine-stereotyped gender roles have caused inequality in the representation of the LGBTQIA+ community. Although there are openly gay male dancers in ballet, their roles pressure them to adhere to rigid ideas of masculinity: the chivalrous prince rescues the helpless female character. Historically, the Romantic era brought the ballerina to the forefront, and ballet became perceived as a feminine art form. Dancers who identify as lesbians are excluded from the ballet narrative because movement qualities reinforce binary norms.

The representation gap for all sexual orientations has excluded people in the LGBTQIA+ community. Many feel the pressure to conform to rigid gender stereotypes. LGBTQIA+ artists today are using their platforms to address the lack of representation and challenge ballet traditions to include a wide spectrum of sexuality.

Les Ballets Trockadero de Monte Carlo

Les Ballets Trockadero de Monte Carlo adds a twist of humor to classical ballets. The company, founded in 1974, features men performing en travesti (in the clothing of the opposite sex.) The dancers in this company challenge the gender norms of ballet by assigning men to traditionally female roles.

Watch This

Les Ballets Trockadero de Monte Carlo’s version of Swan Lake. In the pas de quatre, or dance of four, the dancers perform a parody of the Dance of the Little Swans.

Ballez

Ballez is a ballet company founded by Katy Pyle in 2011. Ballez aims to dismantle the patriarchal structure of ballet to create inclusive spaces for the representation of queer dancers. In 2021, Pyle reimagined the romantic ballet Giselle. In Ballez’s production Giselle of Loneliness, Ballez highlights the experiences of queer and gender non-conforming, non-binary, and trans dancers. The dancers perform an audition solo inspired by the “mad scene” from the original Giselle that comments on the personal challenges and experiences affecting their relationship with ballet from an LGBTQIA+ lens.

Watch This

An interview with Katy Pyle:

Body Types

Generally, ballet centers on European aesthetics, including the ideal body shape. George Balanchine, the founder of New York City Ballet, favored a ballet dancer with a long neck, sloped shoulders, a small rib cage, a narrow waist, and long legs and feet. These ideals have resulted in the pressure to maintain a slender physique and have caused body dysmorphia in many dancers. Copeland has stated that at the age of 21, artistic staff commented on how her body “changed” and their hopes to see her body “lengthen.” According to Copeland, “That, of course, was a polite, safe way of saying, ‘You need to lose weight.’” In 2017, Misty Copeland released her health and fitness book Ballerina Body: Dancing and Eating Your Way to a Leaner, Stronger, and More Graceful You. Copeland shares her health-conscious approaches to developing healthier and stronger bodies in this book.

Ballet Timeline

Summary

Ballet is a Western classical dance form with a rich history—beginning in the Renaissance as a royal court entertainment infused with social and political purposes, eventually developing into a codified technique. Over time, ballet transformed, experiencing costume changes in the Enlightenment that led to dancers being able to express themselves without being confined to restrictive clothing. In the Romantic era, ballet d’action emerged, emphasizing emotions over logic to help communicate the ballet’s story. There were also technical elements such as flying machines that gave the impression of dancers floating onstage. The unique theater effects led to female dancers beginning to dance en pointe. During the classical period, Russia became the leader of ballet, with government support to establish ballet schools. Ballet shifted in pursuit of virtuosity, demanding greater technique from dancers. The Ballet Russes made a significant impact by modernizing ballets, bringing ballet to other world regions, and helping establish ballet in America, and a new ballet style was formed, neoclassical. Today, choreographers challenge the ballet traditions and embrace various dance genres to blend with ballet in contemporary dance.

Check Your Understanding

1. Ballet Pantomime

Choreograph a short pantomime that tells a story through dialogue. You may either choose to ask a friend or family member to exchange dialogue or perform your dance alone. Use a combination of traditional pantomime gestures from the selected videos and add original gestures and facial expressions. Record your pantomime and share the link on the discussion board (minimum of 20 seconds). Include a script summarizing what your pantomime says.

Here are some topic examples you might consider:

Activities or sports you like to participate in and why.

What makes you happy (taking walks, spending time with friends, etc.).

Aspects about your day.

A place you’ve traveled to and what you saw.

Words of encouragement/affirmation.

2. Elements of Dance in Ballet

Utilizing the Elements of Dance, watch two videos from different ballet eras (Renaissance, the Enlightenment, the Romantic period, classical, avant-garde, neoclassical, and contemporary), and write a reflection speaking to the salient qualities observed. Answer the following prompts:

Compare and contrast the aesthetics observed using the Elements of Dance.

How does the movement reflect the ballet era? How does the period reflect the movement?

3. Dear Catherine dé Medici

Write a letter to Catherine dé Medici that speaks to the current discourse in the ballet world. Select one of the discussion topics found in this chapter and watch the associated video (race, gender roles, LGBTQIA+ representation, or body types in ballet) to reflect on, respond to, and advocate for how the ballet world can address these issues. Please reference the class book or use the internet to conduct further research. Post your assignment on the discussion board and cite references (minimum of 150 words).

References

“History of Ballet.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, June 24, 2022. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_ballet.

Kassing, Gayle. Discovering Dance. Champaign: Human Kinetics, 2014.

“Ballez.” BALLEZ, www.ballez.org/.

Bried, Erin. “Stretching Beauty: Ballerina Misty Copeland on Her Body Struggles.” SELF, March 18, 2014. https://www.self.com/story/ballerina-misty-copeland-body-struggles.

Harlow, Poppy, and Dalila-Johari Paul. “Misty Copeland Says the Ballet World Still Has a Race Problem and She Wants to Help Fix That.” CNN. Cable News Network, May 21, 2018. https://www.cnn.com/2018/05/21/us/misty-copeland-ballet-race-boss-files/index.html.

Lihs, Harriet R. Appreciating Dance a Guide to the World’s Liveliest Art. Princeton Book Company, 2018.

Loring, Dawn Davis, and Julie L. Pentz. Dance Appreciation. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 2022.

“Ballet.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, July 20, 2022. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ballet.

Ambrosio, Nora. Learning about Dance: Dance as an Art Form & Entertainment. Dubuque, IA: Kendall Hunt Publishing Company, 2018.

forms are structured, and stylized techniques developed and evolved throughout centuries requiring rigorous formal training.

describes a dance form ordered systematically and has set movements associated with specific terminology

is a stationary handrail that supports dancers to hold while working on balance, allowing them to focus on placement and alignment and coordination to prepare for center combinations.

is an outward rotation of the legs in the hip socket.

describes the action of dancers rising to the tips of the toes.

performers use expressive bodily movements or facial expressions to tell a story

is the first recognized ballet.

(court ballet) featured independent acts of dancing, music, and poetry unified by overarching themes. Court ballets adhered to principles of hierarchy that mirrored status in the royal courts.

is a French term, referring to dance schools founded on the principles led by Beauchamps.

describes a series of independent episodes linked by a common theme.

uses symbolic representation to document choreographed dances.

or dramatic ballets rely purely on movement without the aid of speech or songs to convey the story.

or dramatic ballets rely purely on movement without the aid of speech or songs to convey the story.

a stage with a frame or arch

refers to the lowest-ranking members of a ballet company. These ensemble dancers perform unison movements and act as a backdrop that helps feature the principal dancers and soloists.

or “white ballet” refers to the corps de ballet wearing white tutus or dresses, typically representing supernatural characters.

or diversions are short dances incorporated in ballets that aren’t directly related to the story.

refers to a duet for the principal dancers. The grand pas de deux has four sections: adagio, man’s variation, woman’s variation, and coda.

is an abbreviation for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Questioning and/or Queer, Intersex, and Asexual.