9.2 Coming Up with Research Strategies

Rashida Mustafa; Emilie Zickel; and Johannah White

You have chosen a topic on your own, from parameters provided by your instructor or from an assigned topic. You have taken that topic and developed it into a research question or a hypothesis that is arguable and manageable for the length of the assignment. Now it is time to begin your research. But before heading to your favorite search engine and academic databases, first think about what kinds of information you want and/or need.

You may want to begin by asking yourself questions relating to your chosen topic so that you can begin sifting through and perusing sources that you will use to further your understanding of the topic. When you begin the research phase of your essay, you will come across an array of sources that look helpful in the beginning, but once you have a clearer idea of your research topic (it may change as you research), you might see that the sources you were once considering using in your essay are now irrelevant. To make your research efficient, start your research with a research strategy.

A research strategy involves deciding what you need to know to answer your research question.

- What kinds of sources do you need?

- What can different kinds of sources—popular or academic, primary/secondary/tertiary—offer you?

- Whose perspectives could help you to answer your research question?

- What kinds of professionals/scholars will be able to give you the information you seek?

- What keywords should you be using to get the information that you want?

What Should I Be Looking For?

As you seek sources that can help you to answer your research question, think about the types of “voices” you need to hear from.

- Scientists/researchers who have conducted their own research studies on your topic

- Scholars/thinkers/writers who have also looked at your topic and offered their own analyses of it

- Journalists who are reporting on what they have observed

- Journalists/newspaper or magazine authors who are providing their educated opinions on your topic

- Critics, commentators, or others who offer opinions on your topic

- Tertiary sources/fact books that offer statistics or data (usually without analysis)

- Personal stories of individuals who have lived through an event

- Bloggers/tweeters/other social media posters

Any of these perspectives (and more) could be useful in helping you to answer your research question.

Wikipedia

Wikipedia, the place that we have all been told to avoid, can be a great place to get ideas for a research strategy.

Wikipedia can help you to identify key terms, people, events, arguments, or other elements that are essential to understanding your topic. The information that you find on Wikipedia can also offer ideas for keywords that you can use to search in academic databases. Spending a bit of time on Wikipedia can help you to answer essential questions such as:

- Do you have an overview of the topic?

- Are you up-to-date on the current situation/most recent information on your topic?

- Do you know about key events that have shaped any controversies surrounding your topic?

Wikipedia is a wealth of information and much of it can be accurate and valuable. A 2005 study by the journal Nature claimed that the information found on Wikipedia is as accurate as that found in Encyclopedia Britannica. So why shouldn’t you cite Wikipedia as a source in your research paper?

First, because the authorship of the material is unknown.

Second, because the authorship is unknown, the authority of the author is unknown, hence the material is easily called into question. If we do not know who wrote something, we don’t know what his/her qualifications are to write it. In college-level work, we strive to learn from recognized experts in our subject areas.

Third, because Wikipedia is considered an online encyclopedia and college-level papers seek higher quality source materials such as peer-reviewed and academic journals, books from scholarly publishers, and other materials (data sets, reports) that demonstrate a student’s ability to recognize accuracy within source material.

Additionally, Wikipedia possesses the pitfall of being an online “crowd-sourced” resource. On the web, being a “crowd-sourced” resource means that any member of its community can modify it. The problem is two-fold: members of the community do not sign their work—all members remain anonymous. Though modification is overseen by the nonprofit Wikimedia Foundation, hot topic pages, celebrity pages, as well as popular and culturally dissenting events often lead to pages frequently altered with troll-like vandalism.

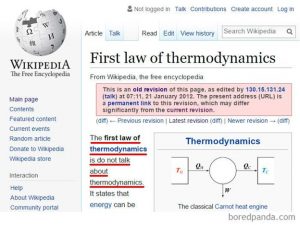

In this excerpt of a vandalized Wikipedia page, you can see that it is not only celebrity and culturally divisive pages that invite modification. Someone has made a joke of the entry to echo the sentiment of the film Fight Club, which may not prove useful to you when doing research on a physics paper.

How to Use Wikipedia—as a Resource, Not a Source

Should you cite Wikipedia? NO.

Should you be using a Wikipedia page as a source? NO.

BUT Wikipedia can give you some wonderful access to the context surrounding your topic and help you to get started. Wikipedia pages provide reference links to most of its information, which you can click on, read, and evaluate for yourself if it is a credible source. In fact, the most valuable part of Wikipedia is the “References Available” section at the bottom of every page. That is where you can start judging the sources used to produce what you have read.

The video below offers more tips on how you can integrate Wikipedia into your research strategy:

“Using Wikipedia for Academic Research” by Michael Baird (Cooperative Library Instruction Project) is licensed under CC BY.